Abstract

BACKGROUND

Data suggest that estrogen-containing hormone therapy is associated with beneficial effects with regard to cardiovascular disease when the therapy is initiated temporally close to menopause but not when it is initiated later. However, the hypothesis that the cardiovascular effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy vary with the timing of therapy initiation (the hormone-timing hypothesis) has not been tested.

METHODS

A total of 643 healthy postmenopausal women were stratified according to time since menopause (<6 years [early postmenopause] or ≥10 years [late postmenopause]) and were randomly assigned to receive either oral 17β-estradiol (1 mg per day, plus progesterone [45 mg] vaginal gel administered sequentially [i.e., once daily for 10 days of each 30-day cycle] for women with a uterus) or placebo (plus sequential placebo vaginal gel for women with a uterus). The primary outcome was the rate of change in carotid-artery intima– media thickness (CIMT), which was measured every 6 months. Secondary outcomes included an assessment of coronary atherosclerosis by cardiac computed tomography (CT), which was performed when participants completed the randomly assigned regimen.

RESULTS

After a median of 5 years, the effect of estradiol, with or without progesterone, on CIMT progression differed between the early and late postmenopause strata (P = 0.007 for the interaction). Among women who were less than 6 years past menopause at the time of randomization, the mean CIMT increased by 0.0078 mm per year in the placebo group versus 0.0044 mm per year in the estradiol group (P = 0.008). Among women who were 10 or more years past menopause at the time of randomization, the rates of CIMT progression in the placebo and estradiol groups were similar (0.0088 and 0.0100 mm per year, respectively; P = 0.29). CT measures of coronary-artery calcium, total stenosis, and plaque did not differ significantly between the placebo group and the estradiol group in either postmenopause stratum.

CONCLUSIONS

Oral estradiol therapy was associated with less progression of subclinical atherosclerosis (measured as CIMT) than was placebo when therapy was initiated within 6 years after menopause but not when it was initiated 10 or more years after menopause. Estradiol had no significant effect on cardiac CT measures of atherosclerosis in either postmenopause stratum. (Funded by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health; ELITE ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00114517.)

After dozens of observational studies consistently showed inverse associations between postmenopausal hormone therapy and the risk of coronary heart disease and death from any cause, it was difficult to understand the null or adverse effects of the therapy on coronary heart disease that were reported from randomized, controlled trials. One explanation is that in observational studies, women were younger (approximately 50 years of age) and closer to menopause (typically within 2 years) when they initiated hormone therapy than were the women included in randomized trials (mean age in the 60s, typically >10 years past menopause). This so-called timing hypothesis posits that the effects of hormone therapy on atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease depend on the timing of the initiation of hormone therapy relative to menopause, age, or both,1-3 which are in turn related to the health of the underlying vascular tissue or to other factors, such as reduction in or down-regulation of estrogen receptors.4,5 Two sister trials — the Estrogen in Prevention of Atherosclerosis Trial (EPAT), which showed a reduction of atherosclerosis progression in association with postmenopausal hormone therapy in women without coronary heart disease,4 and the Women's Estrogen Lipid-Lowering Hormone Atherosclerosis Regression Trial (WELL-HART), which showed no significant effect of hormone therapy on atherosclerosis progression in women with established coronary heart disease5 — provided early clinical trial support for the hormone-timing hypothesis: the results of the trials, with regard to the effect of hormone therapy on the progression of atherosclerosis, differed according to the health of the underlying vascular tissue. After completion of EPAT and WELL-HART, the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) was proposed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in early 2002.

The trial was specifically designed to test the hormone-timing hypothesis in relation to atherosclerosis progression in postmenopausal women. Since the initiation of the trial, the amount of data in support of the hormone-timing hypothesis has grown considerably.1,6 Our primary hypothesis was that postmenopausal hormone therapy would reduce the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis when therapy was initiated soon after menopause (<6 years) but not when therapy was initiated a long time after menopause (≥10 years).

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

ELITE was a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which serial carotid arterial measurements were obtained noninvasively. Participants were healthy postmenopausal women without diabetes and without clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease who had had no regular menses for at least 6 months or who had surgically induced menopause, as well as a serum estradiol level lower than 25 pg per milliliter (92 pmol per liter). At the time of randomization, participants were stratified according to the number of years past menopause: less than 6 years or 10 or more years. The exclusion criteria are described in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

The trial was approved by the University of Southern California institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent. An external data and safety monitoring board appointed by the National Institute on Aging monitored the safety of participants and trial conduct. The trial design, methods, and rationale have been published previously.6 The trial protocol is available at NEJM.org; the first two authors take responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the reporting and for the fidelity of the report to the study protocol.

RANDOMIZATION AND TREATMENT

Participants were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 ratio, to receive oral 17β-estradiol (1 mg daily) or matching placebo within strata of early postmenopause (<6 years since menopause) and late postmenopause (≥10 years since menopause). Additional randomization stratification factors were baseline carotid-artery intima–media thickness (CIMT) (<0.75 or ≥0.75 mm) and hysterectomy status (yes or no). Women in the estradiol group who had a uterus also received micronized progesterone (45 mg) as a 4% vaginal gel, and women in the placebo group who had a uterus received matching placebo gel; the estradiol or placebo gel was to be applied sequentially (i.e., once daily for 10 days during each 30-day cycle). The participants, investigators, staff, imaging specialists, and data monitors were unaware of the treatment assignments.

Teva Pharmaceuticals, Watson Laboratories, and Abbott Laboratories provided the hormone products free of charge. No company had any role in the collection or analysis of data or in the preparation or review of the manuscript or the trial protocol.

FOLLOW-UP

Recruitment was initially based on a 5-year trial (3-year recruitment with 2 to 5 years of randomly assigned treatment or placebo). In the fifth year of follow-up, the trial was extended 2.5 years with supplemental funding from the NIH for collection of additional data, including results of cardiac computed tomography (CT) that was performed when participants completed the course of randomly assigned treatment or placebo. Evaluations of participants (see the Supplementary Appendix) were scheduled monthly in a specialized research clinic for the first 6 months and then every other month until trial completion.

ASSESSMENT OF ATHEROSCLEROSIS PROGRESSION

The primary trial outcome was the rate of change in intima–media thickness of the far wall of the right distal common carotid artery, assessed by means of computer image processing of B-mode ultrasonograms that were obtained at two baseline examinations (averaged to obtain the baseline CIMT value) and every 6 months during trial follow-up.6 High-resolution B-mode ultra-sonographic imaging and CIMT measurement were performed with the use of standardized procedures and with technology that was specifically developed in house for longitudinal measurements of changes in atherosclerosis (patents granted in 2005, 2006, and 2011)4,6-9 (see the Supplementary Appendix). The coefficient of variation for baseline CIMT measurements was 0.69%.

SECONDARY TRIAL OUTCOMES

The secondary end points included measurement of cognition,10 as well as measurement of the degree of coronary atherosclerosis with the use of a 64-slice multidetector CT scanner for cardiac imaging (GE Healthcare). Coronary-artery calcium, defined as a plaque of at least three contiguous pixels (area, 1.02 mm2) with a density greater than 130 Hounsfield units was calculated from the noncontrast CT images with the use of standard methods.6,11,12 Coronary-artery stenosis and plaque quantification were assessed from axial cardiac CT contrast angiographic images, multiplanar reconstructions, and curved maximum-intensity projections to determine the degree of luminal narrowing in all assessable coronary segments at the end-diastolic frame or the frame with smallest amount of motion artifact6,11,12 (see the Supplementary Appendix). Clinical outcome data were collected in a uniform manner with the use of standard queries at each clinical visit, collection of medical records, and completion of standardized adverse and clinical event case-report forms.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The estradiol and placebo groups (the study groups) were compared within time-since-menopause strata with respect to baseline demographic characteristics, medical history, risk factors, previous hormone therapy, estradiol levels, and CIMT with the use of Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Clinical and laboratory variables during the trial were compared between the estradiol and placebo groups with the use of marginal models with generalized estimating equations, with an identity-link function and exchangeable correlation structure. The tests of interest were the overall comparisons between the estradiol and placebo groups in the total sample; adjustments were made for multiple hypothesis testing.13 Covariates included randomization stratification factors and baseline values of clinical and laboratory variables. We also tested for a differential treatment effect according to postmenopause stratum by adding an interaction term. Study-group effects with regard to clinical and laboratory variables measured during the trial were not separately tested within the postmenopause strata. Exact methods were used for the evaluation of adverse events, which was performed in all participants who underwent randomization; event proportions were compared among the four groups (i.e., according to regimen [estradiol vs. placebo] and postmenopausal status [early vs. late]).

The primary outcome was the per-participant rate of change in intima–media thickness in the right distal common carotid artery far wall.4,6 Mixed-effects models were used with study group and postmenopause stratum included as indicator variables. Randomization-stratification variables were included as covariates. Random effects were specified for the participant-specific intercept (baseline CIMT) and slope (CIMT change rate). The overall study-group difference in the mean rate of change in CIMT was tested with a two-way interaction between study group and the number of years in the study. A two-way interaction term of time since menopause and years in the study was used to test whether the mean CIMT progression rates differed between the two postmenopause strata. The primary trial hypothesis that study-group effects on the rate of change in CIMT would differ according to the time since menopause was tested with a three-way interaction term of time since menopause and study-group assignment according to years in the study. Time since menopause was the only prespecified analysis for effect modification. In a sensitivity analysis, CIMT follow-up data were imputed for the 47 participants for whom only the baseline CIMT measurement was available. Follow-up CIMT measurements were imputed at 6-month visits up to 30 months, which was the median follow-up time among 83 participants who had some — but not complete — follow-up. For each participant, CIMT at each visit was imputed, with the mean equal to the participant's baseline CIMT (i.e., no change in CIMT during follow-up) and variance equal to the model residual from the analysis of the complete CIMT data.

Using generalized linear models, we performed study-group comparisons among participants who underwent cardiac CT within 6 months after their final clinic visit and had at least 80% adherence to the study regimen, as assessed by means of a pill count (see the Supplementary Appendix). The cardiac CT angiographic measures were total stenosis score and total plaque score. The coronary-artery calcium measures included calcium score and the presence or absence of any coronary-artery calcium (a dichotomous variable).

Sample size requirements were based on a projected mean difference between the estradiol group and the placebo group in the rate of change in CIMT of 0.0144 mm per year in the early-postmenopause stratum and 0.0021 mm per year in the late-postmenopause stratum and a standard deviation of CIMT change of 0.02 mm per year.4 To test this interaction at 80% power and a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 while allowing for 25% dropout, we estimated that a sample size of 126 in each of the four groups would be required (504 total participants). The sample size was subsequently increased to increase the power to detect interactions between study group and postmenopause stratum.

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

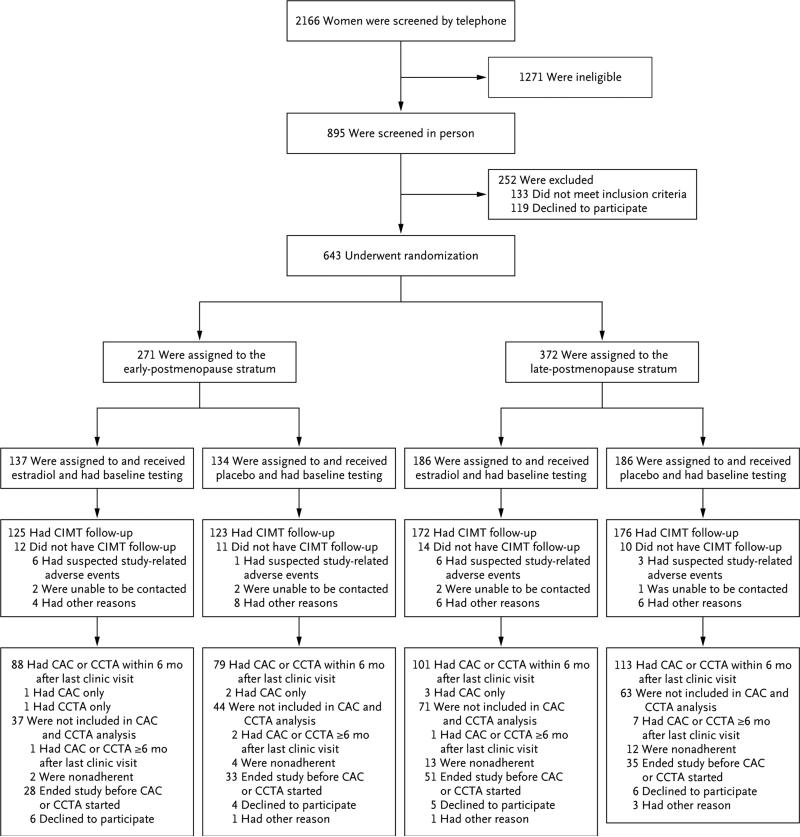

Of the 2166 women who were screened, 643 underwent randomization. Within the early-postmenopause stratum, 271 women underwent randomization, of whom 134 were assigned to receive placebo, and 137 were assigned to receive estradiol; within the late-postmenopause stratum, 372 women underwent randomization, of whom 186 were assigned to receive placebo and 186 were assigned to receive estradiol. A total of 248 women (123 in the placebo group and 125 in the estradiol group) in the early-postmenopause stratum and 348 women (176 in the placebo group and 172 in the estradiol group) in the late-postmenopause stratum had CIMT data included in the analysis of the primary trial end point (Fig. 1); 47 participants did not have CIMT data available for inclusion in the analysis because those women dropped out before undergoing follow-up ultrasonographic examinations.

Figure 1. Study Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

Other reasons for a lack of carotid-artery intima–media thickness (CIMT) follow-up were as follows: in the early-postmenopause stratum, estradiol group, 3 participants were too busy, and 1 did not want to take estradiol; in the early-postmenopause stratum, placebo group, 3 participants moved away from the area, 1 was too busy, 1 was called for armed-services duty, 1 had a competing family issue, 1 was counseled by a physician to withdraw, and 1 did not want to take estradiol; in the late-postmenopause stratum, estradiol group, 2 participants moved away from the area, 1 was too busy, 1 was no longer interested, 1 had a weight increase, and 1 had concern about blood clots; in the late-postmenopause stratum, placebo group, 1 participant moved away from the area, 2 were too busy, 1 was called for armed-services duty, 1 had a competing family issue, and 1 received a diagnosis of breast cancer after undergoing baseline mammography. Other reasons for participants not being included in the coronary-artery calcium (CAC) and cardiac computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) analysis were as follows: in the early-postmenopause stratum, placebo group, 1 participant lost contact; in the late-postmenopause stratum, estradiol group, 1 participant was too busy; in the late-postmenopause stratum, placebo group, 1 participant had an incomplete examination and 2 participants lost contact.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants with CIMT follow-up data (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix provides these data for all participants who underwent randomization). The median age at enrollment was 55.4 years in the early-postmenopause stratum and 63.6 years in the late-postmenopause stratum, and the median time since menopause was 3.5 years in the early-postmenopause stratum and 14.3 years in the late-postmenopause stratum. The mean CIMT was 0.75 mm in the early-postmenopause stratum and 0.79 mm in the late-postmenopause stratum (Table 2). Although most baseline characteristics differed significantly between participants in the early postmenopause stratum and those in the late postmenopause stratum, they did not differ significantly between randomly assigned study groups within each postmenopause stratum, with the exception of age in the late-postmenopause stratum; estradiol-treated women were slightly older, on average, than the women who received placebo.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Characteristics.*

| Variable | Early-Postmenopause Stratum (N = 248) | Late-Postmenopause Stratum (N = 348) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 123) | Estradiol (N = 125) | Placebo (N = 176) | Estradiol (N = 172) | |

| Median time since menopause (IQR) — yr | 3.5 (1.8–4.9) | 3.5 (2.0–5.3) | 14.1 (11.4–18.1) | 14.5 (11.4–18.8) |

| Median age at enrollment (IQR) — yr | 55.4 (52.5–57.8) | 55.4 (53.2–57.9) | 63.0 (59.9–67.0) | 64.3 (60.5–68.6) |

| Race or ethnic background — no. (%)† | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 73 (59.3) | 88 (70.4) | 127 (72.2) | 127 (73.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 14 (11.4) | 7 (5.6) | 14 (8.0) | 17 (9.9) |

| Hispanic | 20 (16.3) | 16 (12.8) | 23 (13.1) | 20 (11.6) |

| Asian | 16 (13.0) | 14 (11.2) | 12 (6.8) | 8 (4.7) |

| Education — no. (%) | ||||

| Less than high school | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 0 |

| High school or some college | 38 (30.9) | 27 (21.6) | 71 (40.3) | 56 (32.6) |

| College graduate | 85 (69.1) | 97 (77.6) | 103 (58.5) | 116 (67.4) |

| Smoking history — no. (%) | ||||

| Current smoker | 4 (3.3) | 5 (4.0) | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.5) |

| Former smoker | 46 (37.4) | 38 (30.4) | 72 (40.9) | 65 (37.8) |

| Never smoked | 73 (59.3) | 82 (65.6) | 100 (56.8) | 101 (58.7) |

| Antihypertension medications — no. (%) | 27 (22.0) | 20 (16.0) | 47 (26.7) | 50 (29.1) |

| Cholesterol-lowering medications — no. (%) | 19 (15.4) | 18 (14.4) | 40 (22.7) | 44 (25.6) |

| Type of menopause — no. (%) | ||||

| Surgical | 3 (2.4) | 6 (4.8) | 32 (18.2) | 26 (15.1) |

| Natural | 120 (97.6) | 119 (95.2) | 144 (81.8) | 146 (84.9) |

| Median body-mass index (IQR)‡ | 26.0 (23.2–29.7) | 26.2 (23.3–30.6) | 26.4 (23.1–29.6) | 27.2 (23.2–31.2) |

| Median blood pressure (IQR) — mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 115 (106–125) | 117 (108–123) | 116 (110–126) | 120 (112–127) |

| Diastolic | 77 (70–81) | 75 (71–80) | 73 (69–78) | 74 (70–79) |

| Median lipid levels (IQR) — mg/dl | ||||

| Cholesterol | 222 (198–247) | 225 (207–245) | 223 (206–243) | 218 (198–242) |

| Triglycerides | 90 (74–129) | 95 (65–119) | 93 (72–129) | 92 (68–133) |

| HDL cholesterol | 63 (51–75) | 63 (54–77) | 66 (55–80) | 63 (53–78) |

| LDL cholesterol | 134 (115–160) | 139 (119–161) | 133 (115–155) | 131 (112–151) |

| Estradiol level (IQR) — pg/ml§ | <10 (<10–12) | <10 (<10–11) | <10 (<10–12.5) | <10 (<10–12) |

| Previous hormone use — no. (%) | 60 (48.8) | 66 (52.8) | 150 (85.2) | 155 (90.1) |

| Current hormone use requiring 1-month washout period — no. (%)¶ | 7 (5.7) | 10 (8.0) | 27 (15.3) | 22 (12.8) |

Included in the table are the 596 participants who were included in the primary and secondary atherosclerosis outcome analyses. The early-postmenopause stratum included women who were less than 6 years past menopause at the time of randomization; the late-postmenopause stratum included women who were 10 or more years past menopause at the time of randomization. Comparisons between the study groups were conducted within postmenopause strata with the use of a Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. The differences between the study groups were not significant (P>0.05), with the exception of age in the late-postmenopause stratum (P=0.03). To convert the values for cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586. To convert the values for triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129. To convert the values for estradiol to picomoles per liter, multiply by 3.671. HDL denotes high-density lipoprotein, IQR interquartile range, and LDL low-density lipoprotein.

Race and ethnic background were self-reported.

Body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

The lower limit of detection is 10 pg per milliliter.

Women who were using hormone therapy stopped use at least 1 month before screening.

Table 2.

Carotid-Artery Intima–Media Thickness (CIMT) Progression and Baseline CIMT.*

| Measure and Postmenopause Stratum | Placebo (N = 299) | Estradiol (N = 297) | P Value† | P Value for Postmenopause Stratum Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean rate of change in CIMT (95% CI) — mm/yr‡ | 0.007 | |||

| Early postmenopause | 0.0078 (0.0060–0.0096) | 0.0044 (0.0026–0.0061) | 0.008 | |

| Late postmenopause | 0.0088 (0.0073–0.0103) | 0.0100 (0.0085–0.0115) | 0.29 | |

| Mean baseline CIMT (95% CI) — mm | ||||

| Early postmenopause | 0.75 (0.73–0.76) | 0.75 (0.73–0.76) | ||

| Late postmenopause | 0.79 (0.77–0.81) | 0.78 (0.77–0.80) |

The median duration of follow-up was 4.8 years (range, 0.5 to 6.7); the median number of CIMT measures per participant was 10 (range, 2 to 13). In the early-postmenopause stratum, the median duration of follow-up was 5.0 years (range, 0.5 to 6.7) in the placebo group and 5.1 years (range, 0.5 to 6.2) in the estradiol group, and the median number of CIMT measures was 11 (range, 2 to 13) in each study group. In the late-postmenopause stratum, the median duration of follow-up was 4.6 years (range, 0.5 to 6.3) in the placebo group and 4.5 years (range, 0.5 to 6.1) in the estradiol group, and the median number of CIMT measures was 10 (range, 2 to 13) in each study group. CI denotes confidence interval.

The P values shown are for the difference between estradiol and placebo within a given postmenopause stratum.

Results were calculated with a mixed-effects model adjusted for the following randomization stratification factors: baseline CIMT (<0.75 mm or ≥0.75 mm) and hysterectomy status (yes or no). In the early-postmenopause stratum, data were available for 123 participants in the placebo group and 125 participants in the estradiol group. In the late-postmenopause stratum, data were available for 176 participants in the placebo group and 172 participants in the estradiol group.

CIMT PROGRESSION RATES

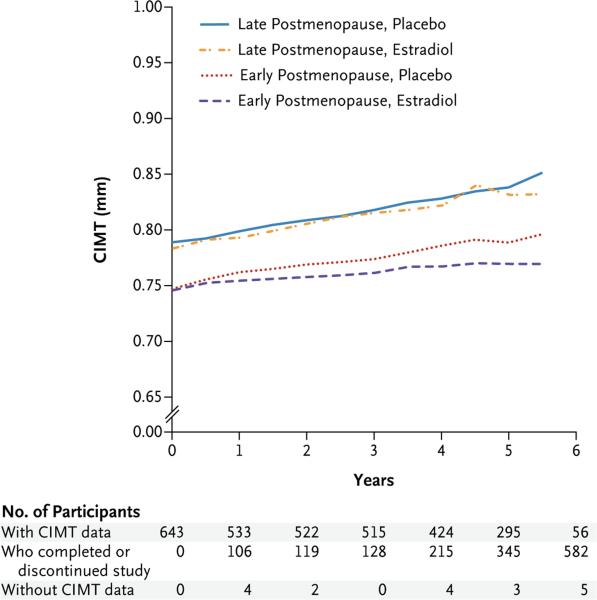

After a median 5-year intervention, the effect of hormone therapy on CIMT progression differed between the early and late postmenopause strata (P = 0.007 for the interaction) (Table 2). In the early-postmenopause stratum, the rate of CIMT progression was significantly lower in the estradiol group than in the placebo group (Fig. 2); the absolute difference between the estradiol and placebo groups in the mean progression rate was −0.0034 mm per year (95% confidence interval [CI], −0.0062 to −0.0008; P = 0.008). In the late-postmenopause stratum, the rates of CIMT progression were similar in the estradiol and placebo groups (difference, 0.0012 mm per year; 95% CI, −0.0009 to 0.0032; P = 0.29). The results were similar in an analysis that was restricted to women who had at least 80% adherence to the intervention (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). In post hoc analyses, the results were similar in women who received estradiol alone and those who received estradiol in combination with progestogen (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix), as well as in women who used lipid-lowering or antihypertensive therapy and those who did not use such therapy (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix). In addition, the results were similar when data were imputed for the 47 participants for whom CIMT data were missing (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). The effect of hormone therapy on the absolute value of CIMT at 5 years also differed significantly between the early and late postmenopause strata (P = 0.03 for the interaction) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. CIMT Progression According to Study Group and Postmenopause Stratum.

At 5 years, the mean absolute CIMT values were as follows: in the late-postmenopause stratum, placebo group (83 participants), 0.838 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.810 to 0.866), and in the estradiol group (72 participants), 0.831 mm (95% CI, 0.805 to 0.857); in the early-postmenopause stratum, placebo group (65 participants), 0.789 mm (95% CI, 0.763 to 0.814), and in the estradiol group (75 participants), 0.770 mm (95% CI, 0.746 to 0.793). The effect of hormone therapy on the absolute value of CIMT at 5 years differed significantly between the postmenopause strata (P = 0.03 for the interaction). In the early-postmenopause stratum, the mean 5-year CIMT was significantly lower in the estradiol group than in the placebo group (P = 0.04); in the late-postmenopause stratum, the mean 5-year CIMT did not differ significantly between the estradiol and placebo groups. Shown at the bottom of the figure for each time point are the numbers of participants for whom CIMT data were available, participants who had completed or discontinued participation in the study, and participants who were still in the study but did not have CIMT data available.

CORONARY ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Cardiac CT was used to evaluate 167 women in the early-postmenopause stratum (79 in the pla cebo group and 88 in the estradiol group) and 214 women in the late-postmenopause stratum (113 in the placebo group and 101 in the estradiol group) (Fig. 1). The majority of participants for whom CT measures were not available had completed follow-up before the addition of these outcomes to the trial (Fig. 1). The frequency of missing data was similar between the study groups and between the two postmenopause strata. Although the measures of coronary atherosclerosis were significantly greater among women in the late-postmenopause stratum than among those in the early-postmenopause stratum, the CT measures did not differ significantly between the placebo and estradiol groups within either postmenopause stratum (Table 3). (The characteristics of the women for whom CT measures were available and of women for whom CT measures were not available are described in the Supplementary Results section of the Supplementary Appendix.)

Table 3.

Measures of Coronary-Artery Atherosclerosis.*

| Coronary-Artery Outcome | Placebo† | Estradiol‡ | P Value | P Value for Postmenopause Stratum Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-squares mean CAC score (95% CI)§ | 0.36 | |||

| Early postmenopause | 1.03 (0.48–1.58) | 1.21 (0.70–1.73) | 0.57 | |

| Late postmenopause | 2.26 (1.84–2.67) | 2.04 (1.61–2.47) | 0.46 | |

| CAC present — % | 0.29 | |||

| Early postmenopause | 30.4 | 39.1 | 0.16 | |

| Late postmenopause | 57.5 | 56.4 | 0.88 | |

| Least-squares mean CCTA total stenosis score (95% CI) | 0.83 | |||

| Early postmenopause | 1.63 (0.77–2.49) | 1.68 (0.88–2.48) | 0.92 | |

| Late postmenopause | 2.90 (2.26–3.55) | 2.81 (2.12–3.49) | 0.84 | |

| Least-squares mean CCTA total plaque score (95% CI) | 0.35 | |||

| Early postmenopause | 1.59 (0.70–2.49) | 1.84 (1.01–2.68) | 0.53 | |

| Late postmenopause | 3.05 (2.38–3.72) | 2.64 (1.93–3.35) | 0.47 |

A total of 381 participants had coronary-artery calcium (CAC) data, cardiac computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) data, or both; 380 had CAC data; and 375 had CCTA data. Participants who were not taking the study agents at the last follow-up visit, who had adherence to the study regimen that was lower than 80%, or who had a CAC or CCTA scan more than 6 months after the final study visit were not included in the analysis. Generalized linear models were adjusted for randomization stratification factors (baseline CIMT and hysterectomy status) and final study visit.

In the placebo group, CAC data were available for 192 women (79 in the early-postmenopause stratum and 113 in the late-postmenopause stratum), and CCTA data were available for 190 women (77 in the early-postmenopause stratum and 113 in the late-postmenopause stratum).

In the estradiol group, CAC data were available for 188 women (87 in the early-postmenopause stratum and 101 in the late-postmenopause stratum), and CCTA data were available for 185 women (87 in the early-postmenopause stratum and 98 in the late-postmenopause stratum).

The CAC score is calculated as log(CAC level + 1).

ADHERENCE

In the early-postmenopause stratum, the median percentage adherence to the study regimen, as assessed by means of pill counting, was 98% (interquartile range, 93 to 100) in the placebo group and 98% (interquartile range, 96 to 100) in the estradiol group; the respective adherence rates in the late postmenopause stratum were 98% (interquartile range, 94 to 100) and 98% (interquartile range, 93 to 100). Estradiol levels in serum during the trial were at least 3 times as high among women who were assigned to active treatment as among women who received placebo (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

CHANGES IN METABOLIC AND CLINICAL VARIABLES

During the trial, the mean levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol were significantly lower — and the mean levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and total triglyceride levels were significantly higher — in the estradiol group than in the placebo group. Body-mass index and blood pressure during the trial did not differ significantly between the study groups. The between-group differences in metabolic and clinical variables were similar in the early and late-postmenopause strata (Tables S6 and S7 in the Supplementary Appendix).

ADVERSE EVENTS

Serious adverse events occurred in 45 women who were assigned to receive placebo and in 43 women who were assigned to receive estradiol (Table S8 in the Supplementary Appendix). These included two deaths (one from pancreatic cancer [placebo group] and one from glioblastoma [estradiol group]). The other serious adverse events were breast cancer (8 women who received placebo and 10 women who received estradiol), myocardial infarction (3 women and 1 woman, respectively), and deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (2 women and 3 women, respectively). The frequency of none of these clinical events differed significantly between the placebo and estradiol groups in either postmenopause stratum.

DISCUSSION

In this randomized controlled trial, the effect that estradiol therapy, with or without progesterone, had on CIMT progression was significantly modified by time since menopause (P = 0.007 for the interaction). The rate of CIMT progression was significantly lower in the estradiol group than in the placebo group among women who were less than 6 years past menopause but not among women who were 10 or more years past menopause.

These results are consistent with results of other studies that have suggested that the effects of hormone therapy on cardiovascular disease may depend on the timing of therapy initiation relative to menopause.6 In large meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, including the Women's Health Initiative, a significantly lower risk of coronary heart disease (hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.96) and of death from any cause (hazard ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.95) was found with hormone therapy than with placebo among women who were younger than 60 years of age, less than 10 years past menopause, or both when they underwent randomization; however, such differences between hormone therapy and placebo were not found among women who were 60 years of age or older, 10 or more years past menopause, or both.14-18 In the Women's Health Initiative 13-year follow-up, the effects of therapy with conjugated estrogens alone on myocardial infarction (a secondary end point) were significantly modified by age (P = 0.007 for the interaction): in the group of women who were 50 to 59 years of age at randomization, the risk of myocardial infarction among those who received conjugated estrogens was 40% lower than the risk among those who received placebo; this effect was not seen among women who were 60 years of age or older at randomization.19 The Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study, which involved a cohort of women who were, on average, 50 years of age and 7 months past menopause when they were randomly assigned to receive estradiol alone or in combination with sequential norethisterone acetate, showed a significantly lower risk of coronary heart disease at 10 years and 16 years of follow-up among women who received treatment than among women who received no treatment; however this was a relatively small trial.20

In contrast, in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS), low-dose treatment with oral conjugated estrogens (0.45 mg per day) or patch estradiol (50 μg per day) with oral progesterone (200 mg for 12 days per month) among women at low baseline risk for cardiovascular disease had no significant effect on CIMT progression.21 The apparent dose–response effect of estradiol at the arterial wall level22-24 could explain the discrepancy between the KEEPS results and the results of our trial. Studies in nonhuman primates and other animal species have shown that estrogen therapy prevents atherosclerosis when therapy is initiated at the time of menopause but not when it is initiated some time later.3,25,26

The effects of hormone therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors did not differ between the early and late postmenopause strata in our trial. Previous studies have suggested that the number or functional level of estrogen receptors and the health of the vasculature at the time of exposure to estrogen are important factors in determining whether the arterial wall responds positively to hormone therapy.4,5,27-29 Consistent with this supposition is our finding of an inverse association between baseline CIMT and plasma total estradiol level in the early but not the late postmenopause stratum in our cohort.6

In contrast to our CIMT findings, there were no significant differences in post-treatment coronary-artery calcium and cardiac CT angiographic outcomes between the estradiol and placebo groups in either postmenopause stratum with a mean 6 years of follow up. These results differ from those in the Women's Health Initiative study; at a mean of 7.4 years of follow-up, coronary-artery calcium scores were lower among women who were randomly assigned to receive conjugated estrogens than among those assigned to receive placebo.30 It is possible that the sample size and duration of follow-up in our trial were insufficient to allow detection of between-group differences in the coronary-artery outcomes. However, our findings are consistent with those of other randomized trials that have shown no significant effects of hormone therapy on angiographically demonstrable coronary-artery lesions (established lesions).5,31,32 Studies in animals have shown the effectiveness of hormone therapy in preventing arterial lesion formation but not in reversing established lesions.3,25 Baseline coronary-artery imaging was not available in our study, and thus we could not assess the effects of hormone therapy on the development of new coronary-artery lesions.

Although the CIMT methods and the technology used in our trial predict cardiovascular events and correlate with the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis, as determined by sequential quantitative coronary angiography33,34 (see the Supplementary Appendix), CIMT is not the only predictor of cardiovascular events. Exogenous estrogen affects factors other than CIMT in a manner that may increase the risk of thrombotic events; these factors include coagulation factors, fibrinolysis, and matrix metalloproteinase, an enzyme involved in plaque rupture.35

Serious adverse events were uncommon in our trial, and their rates did not differ significantly between the estradiol and placebo groups. The Women's Health Initiative, a larger trial that involved participants whose mean age was 63 years and mean time beyond menopause was 13.4 years at enrollment, showed higher risks of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, and venous thromboembolism in association with daily continuous combined oral conjugated estrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate therapy, whereas these risks were not reported in some other studies, including a smaller trial with 10 years of hormone therapy and a total of 16 years of follow-up after initiation of hormone therapy in younger women who were much closer to menopause.20 The absolute risks of these outcomes were low and were even lower among women who were 50 to 59 years of age at randomization. Relative to placebo, treatment with oral conjugated estrogens alone was associated with a lower risk of breast cancer among women of all ages19,36; in the subgroup of women who were 50 to 59 years of age at randomization, there was a protective effect of conjugated estrogens alone with regard to the incidence of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and death from any cause, in contrast to a trend toward increased risks of these outcomes among women who were 60 years of age or older at randomization.19,37

In conclusion, we found that the effects of estradiol (with or without progesterone) on the progression of atherosclerosis, assessed as CIMT, differed according to the time of initiation of therapy, with benefit noted when it was initiated in women who were less than 6 years past menopause but not when it was initiated in women who were 10 or more years past menopause. However, we did not find an effect of timing of estradiol treatment relative to menopause with regard to CT measures of coronary atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (R01AG-024154-01-05, R01AG-024154-06-08, and R01AG-024154-S2).

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. The timing hypothesis and hormone replacement therapy: a paradigm shift in the primary pre vention of coronary heart disease in women. 1. Comparison of therapeutic efficacy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1005–10. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodis HN, Mack WJ. The timing hypothesis and hormone replacement therapy: a paradigm shift in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women. 2. Comparative risks. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1011–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarkson TB. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2007;14:373–84. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e31803c764d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Lobo RA, et al. Estrogen in the prevention of atherosclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:939–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Azen SP, et al. Hormone therapy and the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis in post-menopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:535–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, et al. Methods and baseline cardiovascular data from the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol testing the menopausal hormone timing hypothesis. Menopause. 2015;22:391–401. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, et al. Alpha-tocopherol supplementation in healthy individuals reduces low-density lipoprotein oxidation but not atherosclerosis: the Vitamin E Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (VEAPS). Circulation. 2002;106:1453–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029092.99946.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selzer RH, Hodis HN, Kwong-Fu H, et al. Evaluation of computerized edge tracking for quantifying intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery from B-mode ultrasound images. Atherosclerosis. 1994;111:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selzer RH, Mack WJ, Lee PL, Kwong-Fu H, Hodis HN. Improved common carotid elasticity and intima-media thickness measurements from computer analysis of sequential ultrasound frames. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:185–93. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson VW, St John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognition, mood, and physiological concentrations of sex hormones in the early and late postmenopause. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312353110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multi-detector row coronary computed tomo-graphic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1724–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salpeter SR, Walsh JME, Greyber E, Salpeter EE. Coronary heart disease events associated with hormone therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:363–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salpeter SR, Walsh JM, Greyber E, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Mortality associated with hormone replacement therapy in younger and older women: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salpeter SR, Cheng J, Thabane L, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE. Bayesian meta-analysis of hormone therapy and mortality in younger postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122:1016–22. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Liu H, Sal-peter EE. The cost-effectiveness of hormone therapy in younger and older post-menopausal women. Am J Med. 2009;122:42–52. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD002229. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002229.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schierbeck LL, Rejnmark L, Tofteng CL, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e6409. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harman SM, Black DM, Naftolin F, et al. Arterial imaging outcomes and cardiovascular risk factors in recently menopausal women: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:249–60. doi: 10.7326/M14-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostberg JE, Storry C, Donald AE, Attar MJ, Halcox JP, Conway GS. A dose-response study of hormone replacement in young hypogonadal women: effects on intima media thickness and metabolism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:557–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieberman EH, Gerhard MD, Uehata A, et al. Estrogen improves endothelium-dependent, flow-mediated vasodilation in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:936–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vehkavaara S, Hakala-Ala-Pietilä T, Virkamäki A, et al. Differential effects of oral and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on endothelial function in post-menopausal women. Circulation. 2000;102:2687–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenfeld ME, Kauser K, Martin-McNulty B, Polinsky P, Schwartz SM, Rubanyi GM. Estrogen inhibits the initiation of fatty streaks throughout the vasculature but does not inhibit intra-plaque hemorrhage and the progression of estab lished lesions in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:251–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarhouni K, Guihot AL, Vessières E, et al. Determinants of flow-mediated outward remodeling in female rodents: respective roles of age, estrogens, and timing. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1281–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrington DM, Espeland MA, Crouse JR, III, et al. Estrogen replacement and brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation in older women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1955–61. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losordo DW, Kearney M, Kim EA, Jekanowski J, Isner JM. Variable expression of the estrogen receptor in normal and atherosclerotic coronary arteries of premenopausal women. Circulation. 1994;89:1501–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Post WS, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Wilhide CC, et al. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene is associated with aging and atherosclerosis in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:985–91. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary- artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan KB, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronary-artery atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:522–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waters DD, Alderman EL, Hsia J, et al. Effects of hormone replacement therapy and antioxidant vitamin supplements on coronary atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2432–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, et al. The role of carotid arterial intima-media thickness in predicting clinical coronary events. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:262–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-4-199802150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mack WJ, LaBree L, Liu CR, Selzer RH, Hodis HN. Correlations between measures of atherosclerosis change using carotid ultrasonography and coronary angiography. Atherosclerosis. 2000;150:371–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang J, Hodis HN, Hsiai TK, Asatryan L, Sevanian A. Role of annexin II in estrogen-induced macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity: the modulating effect of statins. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295:1647–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsia J, Langer RD, Manson JE, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease: the Women's Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:357–65. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.