Abstract

Background

Although preterm birth less than 37 weeks gestation is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality in the United States, the majority of data regarding preterm neonatal outcomes come from older studies, and many reports have been limited to only very preterm neonates. Delineation of neonatal outcomes by delivery gestational age is needed to further clarify the continuum of mortality and morbidity frequencies among preterm neonates.

Objective

We sought to describe the contemporary frequencies of neonatal death, neonatal morbidities, and neonatal length of stay across the spectrum of preterm gestational ages.

Study Design

Secondary analysis of an obstetric cohort of 115,502 women and their neonates who were born in 25 hospitals nationwide, 2008–2011. All live born non-anomalous singleton preterm (23.0–36.9 weeks of gestation) neonates were included in this analysis. The frequency of neonatal death, major neonatal morbidity (intraventricular hemorrhage grade III/IV, seizures, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, necrotizing enterocolitis stage II/III, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, persistent pulmonary hypertension), and minor neonatal morbidity (hypotension requiring treatment, intraventricular hemorrhage grade 1/2, necrotizing enterocolitis stage 1, respiratory distress syndrome, hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment) were calculated by delivery gestational age; each neonate was classified once by the worst outcome they met criteria for.

Results

8,334 deliveries met inclusion criteria. There were 119 neonatal deaths (1.4%). 657 (7.9%) neonates had major morbidity, 3,136 (37.6%) had minor morbidity, and 4,422 (53.1%) survived without any of the studied morbidities. Deaths declined rapidly with each advancing week of gestation. This decline in death was accompanied by an increase in major neonatal morbidity, which peaked at 54.8% at 25 weeks of gestation. As frequencies of death, and major neonatal morbidity fell, minor neonatal morbidity increased, peaking at 81.7% at 31 weeks of gestation. The frequency of all morbidities fell beyond 32 weeks. Neonatal length of hospital stay decreased significantly with each additional completed week of pregnancy; among babies delivered from 26 to 32 weeks of gestation, each additional week in utero reduced the subsequent length of neonatal hospitalization by a minimum of 8 days. The median post-menstrual age at discharge nadired at 35.7 weeks post-menstrual age for babies born at 32–33 weeks of gestation.

Conclusions

Our data show that there is a continuum of outcomes, with each additional week for gestation conferring survival benefit while reducing the length of initial hospitalization. These contemporary data can be useful for patient counseling regarding preterm outcomes.

Keywords: neonatal morbidity, neonatal mortality, prematurity

Introduction

Preterm delivery less than 37 weeks of gestation remains the leading cause of neonatal and childhood morbidity among non-anomalous infants in the United States and the developed world, and is the leading cause of death worldwide.1–3 Recent advances in perinatal and neonatal medicine have resulted in substantial improvements in outcomes among premature infants.4–6 A large study by the Neonatal Research Network found improvements in rates of death and major morbidity among neonates delivered at 23–24 weeks of gestation between 2009–2012, after outcomes had been relatively static between 1993–2008.6 Despite this, rates of neonatal morbidity remain high, particularly among the most premature neonates. The majority of data regarding preterm neonatal death and morbidity come from older studies. Additionally, many studies have been limited to include only very preterm neonates, and frequently have focused on outcomes by birthweight cutoffs.4,7–9 Outcomes by birthweight may be skewed by inclusion of more mature neonates with growth restriction.4,8

Gestational age at delivery is one of the major determinants of neonatal survival and morbidity. Clinicians and researchers commonly classify women with PTB as delivering ‘early preterm’ or ‘late preterm.’ ‘Early’ PTB is typically regarded as delivery prior to 32 or 34 weeks of gestation, while those delivering 34–36 weeks of gestation are considered to have ‘late’ PTB. Although these designations are somewhat arbitrary, grouping women into PTB delivery epochs may help facilitate research and clinical prevention strategies.

Indeed, women presenting with symptoms of preterm labor prior to 34 weeks have been treated more aggressively with corticosteroids and tocolysis, whereas those with the same symptoms after 34 weeks generally have not received these interventions. Additionally, previous research has suggested that the etiologies of PTB likely vary by gestational age, with those of later PTB being much more heterogeneous.10,11 Indeed, infants delivered at the earliest gestational ages are at highest risk for adverse outcomes during the neonatal period and beyond, as effects of prematurity may persist through childhood and adolescence.7,12,13 In contrast, although infants delivered 34–36 weeks of gestation comprise the largest subset of preterm babies (~75%), they generally have a more benign course compared to their early preterm counterparts. However, late preterm infants continue to have an increased frequency of both immediate and long-term morbidity and mortality compared with term neonates.14–17 Limited evidence-based interventions to improve outcomes in the late preterm cohort exist, although studies are underway to assess efficacy of treatments traditionally reserved for earlier neonates (e.g., antenatal corticosteroid administration). Delineation of neonatal outcomes by delivery gestational age is needed to further clarify the continuum of mortality and morbidity frequencies among preterm neonates.

Thus, this study was designed to describe the contemporary frequencies of neonatal death, major and minor neonatal morbidity, and neonatal length of hospital stay across the spectrum of preterm gestational ages (23 – 36 weeks of gestation) in singletons. We also sought to describe cause of neonatal death across different preterm gestational ages.

Materials and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of the previously described NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network Assessment of Perinatal Excellence (APEX) obstetric cohort.18,19 Briefly, the APEX study was an observational study designed to assist in the development of quality measures for intrapartum obstetric care. Patients eligible for data collection were those who were at least 23 weeks of gestation, had a live fetus on admission and delivered during the 24-hour period of randomly selected days representing one-third of deliveries at 25 hospitals nationwide between 2008–2011; the main study included 115,502 women. Infants were followed until discharge or 120 days of age, whichever came first. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained at each participating institution under a waiver of informed consent. This secondary analysis was reviewed by the University of Utah IRB and deemed exempt.

For the purposes of this secondary analysis, we included all liveborn, non-anomalous singleton neonates delivered 23–36 weeks of gestation. Gestational age was determined by best obstetrical estimate available at the time of admission. Women with inadequate pregnancy dating [e.g., pregnancies dated by last menstrual period only (without ultrasound confirmation) or by third trimester ultrasound only] were excluded. Neonates who were not resuscitated and died in the delivery room were excluded (i.e., only neonates offered a trial of life were included).

The primary outcomes were neonatal death, major neonatal morbidity (intraventricular hemorrhage grade III or IV, seizures, hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, necrotizing enterocolitis stage II or III, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, or persistent pulmonary hypertension) and minor neonatal morbidity (hypotension requiring treatment, intraventricular hemorrhage grade I or II, necrotizing enterocolitis stage I, respiratory distress syndrome, and/or hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment) during the initial hospitalization. Each neonate was categorized into the most severe category they met criteria for (death, major, or minor morbidity). Those without any of the aforementioned morbidities were considered to have no neonatal morbidity.

We also examined presumed cause of death among neonates who died during the initial hospitalization. Research staff reported the cause or causes of death for each neonate as applicable if available in the neonate’s chart. We grouped suspected causes of death into general classifications for the purposes of analysis. In some instances, more than one cause of death was included for each neonate. For example, we considered sepsis, pneumonia, and cytomegalovirus infections together as an ‘infectious’ etiology. The causes of death listed for each neonate were limited to what was listed by research staff under ‘cause of death.’ If an infant was also noted to have one or more serious comorbidities (e.g., hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy), these morbidities were not included in our cause(s) of death classification if they had not been listed as a ‘cause of death’. Neonates with ‘prematurity’ listed as the sole cause of death were considered to have no identifiable cause of death. Suspected causes of death were examined by gestational age at delivery, with babies grouped into 2 week epochs due to small numbers.

The primary outcome frequencies of neonatal death, major neonatal morbidity, and minor neonatal morbidity, were calculated for each completed week of gestation from 23–36 weeks of gestation. Median length of hospital stay and postmenstrual age at discharge among survivors were also calculated. Tests for trend across each completed week of gestation were performed using the Cochran-Armitage trend test for categorical variables and Jonckheere-Terpstra test for continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed; P<0.05 was used to define statistical significance. There was no adjustment for multiple comparisons and no imputation for missing data was performed. Data were analyzed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

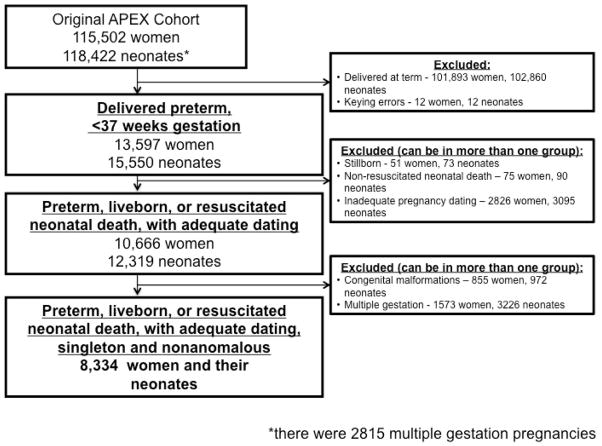

From the original APEX cohort of 115,502 deliveries, 8,334 women and their neonates met inclusion criteria for this analysis (Figure 1). Overall, 13% of women were transferred from another hospital. Baseline and demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1, stratified by delivery gestational age. In general, babies born at the earliest gestational ages were delivered by mothers who were more likely to be nulliparous and non-Hispanic Black, and less likely to have received prenatal care (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study inclusion.

Table 1.

Demographic, medical, and obstetric history by gestational age at delivery. Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

| Clinical Variable | Delivery gestational age (weeks) | P for trend |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 (n=43) |

24 (n=114) |

25 (n=124) |

26 (n=169) |

27 (n=159) |

28 (n=196) |

29 (n=213) |

30 (n=262) |

31 (n=312) |

32 (n=451) |

33 (n=639) |

34 (n=1058) |

35 (n=1477) |

36 (n=3117) |

||

| Maternal age, mean ± SD | 27.0 ±7.1 | 25.5 ±5.9 | 28.0 ±6.8 | 27.3 ±6.6 | 27.9 ±7.2 | 27.4 ±6.5 | 27.3 ±6.7 | 28.3 ±7.2 | 27.2 ±6.5 | 27.9 ±6.5 | 28.4 ±6.4 | 28.3 ±6.4 | 28.5 ±6.4 | 28.4 ±6.4 | .001 |

| Race/ethnicity* Non-Hispanic white |

14 (32.6) | 45 (39.5) | 47 (37.9) | 55 (32.5) | 56 (35.2) | 72 (36.7) | 87 (40.9) | 118 (45.0) | 129 (41.4) | 207 (45.9) | 296 (46.3) | 465 (44.0) | 650 (44.0) | 1381 (44.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 20 (46.5) | 45 (39.5) | 40 (32.3) | 74 (43.8) | 61 (38.4) | 74 (37.8) | 77 (36.2) | 83 (31.7) | 91 (29.2) | 145 (32.2) | 178 (27.9) | 257 (24.3) | 369 (25.0) | 758 (24.3) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 5 (11.6) | 15 (13.2) | 22 (17.7) | 24 (14.2) | 29 (18.2) | 30 (15.3) | 32 (15.0) | 37 (14.1) | 64 (20.5) | 73 (16.2) | 125 (19.6) | 234 (22.1) | 329 (22.3) | 695 (22.3) | .008 |

| Insurance Private |

16 (37.2) | 42 (36.8) | 43 (34.7) | 62 (36.9) | 56 (35.2) | 70 (35.9) | 78 (37.0) | 103 (39.6) | 114 (36.8) | 157 (35.0) | 275 (43.4) | 426 (40.6) | 641 (43.7) | 1431 (46.1) | |

| Government assisted | 22 (51.2) | 63 (55.3) | 69 (55.7) | 93 (55.4) | 89 (56.0) | 111 (56.9) | 107 (50.7) | 138 (53.1) | 175 (56.5) | 257 (57.4) | 312 (49.2) | 532 (50.7) | 677 (46.2) | 1382 (44.5) | <.001 |

| Uninsured or self pay | 5 (11.6) | 9 (7.9) | 12 (9.7) | 13 (7.7) | 14 (8.8) | 14 (7.2) | 26 (12.3) | 19 (7.3) | 21 (6.8) | 34 (7.6) | 47 (7.4) | 92 (8.8) | 148 (10.1) | 292 (9.4) | .37 |

| Prenatal care | 33 (86.8) | 99 (94.3) | 105 (93.8) | 132 (89.8) | 135 (92.5) | 167 (94.4) | 192 (97.0) | 237 (96.3) | 279 (96.9) | 421 (98.8) | 579 (97.2) | 962 (97.2) | 1375 (98.4) | 2938 (98.7) | <.001 |

| BMI at delivery, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29.7 ±7.0 | 31.0 ±8.6 | 31.3 ±7.9 | 31.8 ±6.8 | 30.6 ±7.1 | 31.1 ±8.1 | 31.8 ±8.3 | 31.2 ±7.9 | 31.3 ±7.8 | 31.2 ±7.8 | 31.6 ±7.5 | 31.5 ±7.1 | 31.6 ±7.5 | 31.8 ±7.1 | .008 |

| Cigarette use during pregnancy | 9 (20.9) | 16 (14.0) | 22 (17.7) | 28 (16.6) | 25 (15.8) | 39 (19.9) | 42 (19.8) | 45 (17.2) | 59 (18.9) | 88 (19.6) | 114 (17.9) | 166 (15.7) | 223 (15.1) | 420 (13.5) | <.001 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 4 (9.3) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.1) | 5 (3.2) | 5 (2.6) | 5 (2.4) | 16 (6.1) | 12 (3.9) | 18 (4.0) | 21 (3.3) | 27 (2.6) | 54 (3.7) | 99 (3.2) | .98 |

| Cocaine/methamphe tamine use during pregnancy | 2 (4.7) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.2) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 6 (2.3) | 5 (1.6) | 10 (2.2) | 13 (2.0) | 23 (2.2) | 17 (1.2) | 27 (0.9) | .002 |

| Hypertension (chronic, gestational or preeclampsia) | 4 (9.3) | 22 (19.3) | 45 (36.3) | 58 (34.3) | 53 (33.3) | 77 (39.3) | 84 (39.4) | 123 (47.0) | 132 (42.3) | 173 (38.4) | 209 (32.8) | 322 (30.4) | 393 (26.6) | 813 (26.1) | <.001 |

| Pregestational Diabetes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.8) | 7 (5.7) | 5 (3.0) | 6 | 7 (3.8) | 6 (2.8) | 11 (4.2) | 23 (7.4) | 26 (5.8) | 31 (4.9) | 62 (5.9) | 69 (4.7) | 127 (4.1) | .31 |

| Anticoagulant use | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 4 (3.2) | 5 (3.0) | 6 (3.8) | 2 (1.0) | 7 (3.3) | 7(2.7) | 11(3.5) | 11 (2.4) | 8 (1.3) | 18 (1.7) | 27 (1.8) | 54 (1.7) | .03 |

| Sexually transmitted disease during pregnancy (chlamydia, gonorrhea or syphilis) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (6.1) | 6 (4.8) | 9 (5.4) | 3 (1.9) | 10 (5.1) | 10 (4.7) | 15 (5.8) | 18 (5.8) | 26 (5.8) | 30 (4.7) | 51 (4.9) | 74 (5.0) | 132 (4.3) | .57 |

| Nulliparous | 23 (53.5) | 59 (51.8) | 52 (41.9) | 78 (46.2) | 66 (41.5) | 83 (42.4) | 101 (47.4) | 126 (48.1) | 132 (42.3) | 203 (45.0) | 262 (41.0) | 435 (41.2) | 575 (38.9) | 1166 (37.4) | <.001 |

| Patient transferred from another hospital | 21 (48.8) | 45 (39.5) | 45 (36.3) | 65 (38.5) | 62 (39.0) | 64 (32.7) | 73 (34.3) | 82 (31.3) | 87 (27.9) | 127 (28.2) | 137 (21.4) | 135 (12.8) | 72 (4.9) | 67 (2.2) | <.001 |

Other self-reported racial/ethnic groups not listed due to small numbers; therefore, percentages do not equal 100.

Labor and delivery outcomes and management characteristics are shown in Table 2. Preterm, premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) was common in this cohort, affecting 34.4% of pregnancies overall. Breech presentation, chorioamnionitis, cervical cerclage, and abruption were more common at the earliest delivery gestational ages, while placenta previa was more common among those delivered at later preterm gestational ages (Table 2). Exposure to antenatal corticosteroids was high overall, ranging from 77.5–93.4% for babies delivered at 24–33 weeks of gestation. Data regarding antenatal magnesium sulfate administration for the purposes of fetal neuroprotection was not initially collected at the start of the study; this variable was added partway through the study, and as a result, data are missing on 57% of the cohort. Among those with data available, use ranged from a peak of 54.2% at 25 weeks gestation to a low of 0.7% at 36 weeks gestation.

Table 2.

Labor and delivery outcomes and management by gestational age at delivery. Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

| Clinical Variable | Delivery gestational age (weeks) | P for trend |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 (n=43) |

24 (n=114) |

25 (n=124) |

26 (n=169) |

27 (n=159) |

28 (n=196) |

29 (n=213) |

30 (n=262) |

31 (n=312) |

32 (n=451) |

33 (n=639) |

34 (n=1058) |

35 (n=1477) |

36 (n=3117) |

||

| Male fetal gender | 24 (55.8) | 58 (50.9) | 58 (46.8) | 87 (51.5) | 100 (62.9) | 107 (54.6) | 111 52.1) | 137 (52.3) | 171 (54.8) | 242 (53.7) | 353 (55.2) | 574 (54.3) | 822 (55.7) | 1672 (53.6) | .62 |

| Presentation Vertex |

21 (50.0) | 50 (44.3) | 74 (59.7) | 95 (56.2) | 95 (60.1) | 138 (70.8) | 144 (67.6) | 202 (77.1) | 244 (78.2) | 375 (83.9) | 550 (86.6) | 938 (88.9) | 1344 (91.2) | 2900 (93.2) | |

| Breech | 21 (50.0) | 59 (52.2) | 47 (37.9) | 67 (39.6) | 55 (34.8) | 52 (26.7) | 59 (27.7) | 54 (20.6) | 57 (18.3) | 61 (13.7) | 75 (11.8) | 104 (9.9) | 113 (7.7) | 190 (6.1) | <.001 |

| Non-breech malpresentation | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) | 3 (2.4) | 7 (4.1) | 8 (5.1) | 5 (2.6) | 10 (4.7) | 6 (2.3) | 11 (3.5) | 11 (2.5) | 10 (1.6) | 13 (1.2) | 17 (1.2) | 21 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Oligohydramnios | 4 (9.3) | 19 (16.7) | 24 (19.4) | 15 (8.9) | 17 (10.8) | 29 (14.8) | 25 (11.7) | 39 (14.9) | 32 (10.3) | 42 (9.3) | 55 (8.6) | 69 (6.5) | 64 (4.3) | 187 (6.0) | <.001 |

| Polyhydramnios | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (2.2) | 5 (1.1) | 7 (1.1) | 12 (1.1) | 17 (1.2) | 32 (1.0) | .48 |

| Placenta previa | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.4) | 3 (1.2) | 8 (2.6) | 13 (2.9) | 20 (3.1) | 37 (3.5) | 33 (2.2) | 78 (2.5) | .03 |

| Abruption | 5 (11.6) | 11 (9.7) | 13 (10.5) | 13 (7.7) | 18 (11.3) | 23 (11.7) | 25 (11.7) | 30 (11.5) | 23 (7.4) | 35 (7.8) | 46 (7.2) | 65 (6.1) | 69 (4.7) | 95 (3.1) | <.001 |

| Preterm premature rupture of membranes | 19 (44.2) | 51 (44.7) | 53 (42.7) | 55 (32.5) | 56 (35.2) | 68 (34.7) | 73 (34.3) | 83 (31.7) | 113 (36.2) | 163 (36.1) | 269 (42.1) | 444 (42.0) | 533 (36.1) | 888 (28.5) | <.001 |

| Prolonged membrane rupture* | 6 (14.6) | 34 (31.5) | 28 (25.9) | 35 (22.0) | 37 (25.9) | 60 (31.6) | 51 (25.8) | 63 (25.4) | 70 (23.8) | 102 (23.7) | 130 (21.6) | 177 (17.2) | 73 (5.1) | 121 (4.0) | <.001 |

| Type of labor None (cesarean without labor or induction) |

5 (11.6) | 31 (27.2) | 41 (33.1) | 62 (36.7) | 58 (36.5) | 78 (39.8) | 79 (37.1) | 97 (37.0) | 98 (31.4) | 128 (28.4) | 145 (22.7) | 222 (21.0) | 266 (18.0) | 582 (18.7) | |

| Spontaneous | 36 (83.7) | 75 (65.8) | 74 (59.7) | 96 (56.8) | 88 (55.4) | 96 (49.0) | 105 (49.3) | 113 (43.1) | 141 (45.2) | 220 (48.8) | 321 (50.2) | 445 (42.1) | 812 (55.0) | 1707 (54.8) | <.001 |

| Induced | 2 (4.7) | 8 (7.0) | 9 (7.3) | 11 (6.5) | 13 (8.2) | 22 (11.2) | 29 (13.6) | 52 (19.9) | 73 (23.4) | 103 (22.8) | 173 (27.1) | 391 (37.0) | 399 (27.0) | 828 (26.6) | <.001 |

| Chorioamnionitis and/or temperature > 100.4 F before delivery | 12 (27.9) | 21 (18.4) | 21 (16.9) | 34 (20.1) | 23 (14.5) | 23 (11.7) | 20 (9.4) | 25 (9.5) | 33 (10.6) | 38 (8.4) | 42 (6.6) | 28 (2.7) | 48 (3.3) | 69 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Cerclage | 4 (9.3) | 9 (7.9) | 9 (7.3) | 9 (5.3) | 12 (7.6) | 12 (6.1) | 9 (4.2) | 10 (3.8) | 6 (1.9) | 11 (2.4) | 18 (2.8) | 24 (2.3) | 23 (1.6) | 39 (1.3) | <.001 |

| Antenatal corticosteroids | 33 (76.7) | 102 (89.5) | 112 (90.3) | 144 (85.2) | 139 (87.4) | 178 (90.8) | 199 (93.4) | 235 (89.7) | 270 (86.5) | 388 (86.0) | 495 (77.5) | 420 (39.7) | 216 (14.6) | 252 (8.1) | <.001 |

| Tocolysis for preterm labor within 12 hours of delivery | 11 (29.0) | 24 (28.9) | 23 (27.7) | 37 (34.6) | 23 (22.8) | 35 (29.7) | 43 (32.1) | 33 (20.0) | 41 (19.2) | 69 (21.4) | 74 (15.0) | 47 (5.6) | 52 (4.3) | 30 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Magnesium sulfate tocolysis | 4 (9.3) | 13 (11.4) | 14 (11.3) | 22 (13.0) | 10 (6.3) | 23 (11.7) | 16 (7.5) | 16 (6.1) | 19 (6.1) | 35 (7.8) | 27 (4.2) | 17 (1.6) | 8 (0.5) | 3 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Operative delivery Spontaneous vaginal |

19 (61.3) | 36 (33.3) | 49 (39.5) | 54 (32.1) | 51 (32.3) | 65 (33.2) | 83 (39.0) | 100 (38.5) | 127 (41.1) | 221 (49.0) | 330 (51.8) | 599 (56.6) | 872 (59.2) | 1808 (58.1) | |

| Vacuum or forceps vaginal | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | 6 (1.3) | 17 (2.7) | 26 (2.5) | 54 (3.7) | 124 (4.0) | <.001 |

| Cesarean | 11 (35.5) | 72 (66.7) | 75 (60.5) | 114 (67.9) | 107 (67.7) | 130 (66.3) | 130 (61.0) | 158 (60.8) | 180 (58.3) | 224 (49.7) | 290 (45.5) | 433 (40.9) | 546 (37.1) | 1181 (37.9) | <.001 |

| Birthweight, grams, mean ± SD | 616 ±104 | 644 ±109 | 753 ±169 | 860 ±228 | 991 ±215 | 1095 ±241 | 1259 ±295 | 1366 ±266 | 1594 ±342 | 1796 ±342 | 2061 ±375 | 2295 ±401 | 2570 ±442 | 2810 ±452 | <.001 |

| Meconium staining of amniotic fluid | 3 (7.0) | 9 (7.9) | 10 (8.1) | 8 (4.7) | 11 (6.9) | 3 (1.5) | 8 (3.8) | 11 (4.2) | 18 (5.8) | 16 (3.6) | 23 (3.6) | 34 (3.2) | 65 (4.4) | 122 (3.9) | .03 |

| Highest level of resuscitation within first 30 minutes after birth None |

0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (4.9) | 10 (5.9) | 17 (10.7) | 19 (9.7) | 28 (13.2) | 56 (21.4) | 78 (25.0) | 181 (40.1) | 323 (50.6) | 618 (58.5) | 1083 (73.4) | 2478 (79.6) | |

| Oxygen | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.5) | 6 (4.9) | 2 (1.2) | 7 (4.4) | 20 (10.3) | 20 (9.4) | 34 (13.0) | 39 (12.5) | 66 (14.6) | 78 (12.2) | 135 (12.8) | 131 (8.9) | 262 (8.4) | <.001 |

| Bag and mask with oxygen | 4 (9.5) | 5 (4.4) | 9 (7.3) | 15 (8.9) | 5 (3.1) | 6 (3.1) | 23 (10.8) | 23 (8.8) | 24 (7.7) | 30 (6.7) | 50 (7.8) | 71 (6.7) | 77 (5.2) | 124 (4.0) | <.001 |

| CPAP | 0 (0.0) | 8 (7.0) | 8 (6.5) | 30 (17.8) | 38 (23.9) | 60 (30.8) | 71 (33.3) | 86 (32.8) | 125 (40.1) | 140 (31.0) | 163 (25.5) | 195 (18.5) | 150 (10.2) | 210 (6.8) | <.001 |

| Intubation for ventilation | 30 (71.4) | 81 (71.1) | 83 (67.5) | 96 (56.8) | 80 (50.3) | 87 (44.6) | 66 (31.0) | 54 (20.6) | 42 (13.5) | 32 (7.1) | 19 (3.0) | 33 (3.1) | 27 (1.8) | 28 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Chest compression | 3 (7.1) | 8 (7.0) | 8 (6.5) | 12 (7.1) | 6 (3.8) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | 7 (2.7) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Cardiac medication | 5 (11.9) | 8 (7.0) | 3 (2.4) | 4 (2.4) | 6 (3.8) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | <.001 |

time from membrane rupture to birth greater than 24 hours

There were 119 neonatal deaths (1.4%). Major morbidity was observed in 657 (7.9%) neonates, 3,136 (37.6%) had minor morbidity, and 4,422 (53.1%) survived without any of the studied morbidities.

Deaths declined rapidly with each advancing week of gestation (Table 3). Suspected cause(s) of death for the 119 neonates are listed in Table 4. Those delivered at the earliest gestational ages (23–24 weeks) were most likely to have none of the specific listed causes of death. There were 5 deaths among neonates delivered 31–33 weeks of gestation and no deaths among neonates delivered 34–36 weeks of gestation.

Table 3.

Frequency of death and major, intermediate and minor morbidity. Data are n (%).

| Outcome | Delivery gestational age (weeks) | P for trend |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=8334) |

23 (n=43) |

24 (n=114) |

25 (n=124) |

26 (n=169) |

27 (n=159) |

28 (n=196) |

29 (n=213) |

30 (n=262) |

31 (n=312) |

32 (n=451) |

33 (n=639) |

34 (n=1058) |

35 (n=1477) |

36 (n=3117) |

||

| Death | 119 (1.4) | 19 (44.2) | 36 (31.6) | 15 (12.1) | 19 (11.2) | 13 (8.2) | 4 (2.0) | 4 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Major morbidity* | 657 (7.9) | 19 (44.2) | 60 (52.6) | 68 (54.8) | 88 (52.1) | 64 (40.3) | 43 (21.9) | 48 (22.5) | 36 (13.7) | 22 (7.1) | 39 (8.7) | 27 (4.2) | 46 (4.4) | 42 (2.8) | 55 (1.8) | <.001 |

| Minor morbidity† | 3136 (37.6) | 4 (9.3) | 18 (15.8) | 39 (31.5) | 59 (34.9) | 77 (48.4) | 144 (73.5) | 147 (69.0) | 206 (78.6) | 255 (81.7) | 344 (76.3) | 406 (63.5) | 540 (51.0) | 402 (27.2) | 495 (15.9) | <.001 |

| Survival without any of the above morbidities | 4422 (53.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (1.8) | 5 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 14 (6.6) | 16 (6.1) | 32 (10.3) | 67 (14.9) | 205 (32.1) | 472 (44.6) | 1033 (69.9) | 2567 (82.4) | |

major morbidity includes persistent pulmonary hypertension, intraventricular hemorrhage grade 3/4, seizures, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, necrotizing enterocolitis stage II/III, bronchopulmonary dysplasia

minor morbidity includes intraventricular hemorrhage grade 1/2, necrotizing enterocolitis stage 1, RDS, hyperbilirubinemia requiring treatment, hypotension requiring treatment

Table 4.

Suspected cause(s) of neonatal death. Data are n (%).

| Outcome | Delivery gestational age (weeks) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23–24 (n=55) | 25–26 (n=34) | 27–28 (n=17) | 29–30 (n=8) | 31–33 (n=5) | |

| Infection* | 6 (10.9) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (29.4) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (20.0) |

| Multiorgan system failure | 3 (5.5) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis or bowel perforation | 4 (7.3) | 4 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy or severe intraventricular hemorrhage | 11 (20.0) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (20.0) |

| Respiratory complications† | 19 (34.5) | 10 (29.4) | 2 (11.8) | 6 (75.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Hematologic complications‡ | 5 (9.1) | 5 (14.7) | 3 (17.6) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other listed cause of death§ | 2 (3.6) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| None of the above | 21 (38.2) | 10 (29.4) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) |

includes sepsis, pneumonia, cytomegalovirus

includes respiratory failure, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, pulmonary hypoplasia, primary pulmonary hypertension, pneumothorax

includes acute thromboembolism, pulmonary hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

includes cardiac arrest/cardiopulmonary collapse, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome complications, metabolic acidosis, pulmonary hemorrhage, acute renal failure

The decline in death was accompanied by an increase in major neonatal morbidity, which peaked at 54.8% at 25 weeks of gestation (Table 3). Individual contributors to the diagnosis of major morbidity and other outcomes among infants with major morbidity are shown in Supplementary Table A. Notably, despite advancing gestational age, severe neurologic injury (hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy) was consistently a significant contributor to the composite major morbidity across preterm delivery gestational ages. As frequencies of death and major neonatal morbidity fell, minor neonatal morbidity increased, peaking at 81.7% at 31 weeks of gestation (Table 3). Beyond 32 weeks, the frequency of minor morbidity fell with each advancing week of gestation, and frequencies of major morbidity and death also continued to fall. Individual contributors to the diagnosis of minor morbidity and other outcomes among infants with minor morbidity are shown in Supplementary Table B.

At the earliest gestational ages (until 25 weeks of gestation), the median length of neonatal hospital stay increased each week (compared with the previous week) due to the large number of early deaths among neonates delivered at the youngest gestational ages (Table 5). After 25 weeks, the length of stay decreased significantly with each additional completed week of pregnancy. Among babies delivered from 26 to 32 weeks of gestation, each additional week in utero reduced the subsequent length of neonatal hospitalization by a minimum of 8 days (Table 5). Finally, among surviving neonates, we examined the median post-menstrual age at discharge from the hospital. The median post-menstrual age at discharge decreased progressively with each additional week in utero until a nadir around 36 weeks post-menstrual age was noted for babies born between 31–35 weeks of gestation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Hospital stay and post-menstrual age at discharge.

| Median (IQR) | Delivery gestational age (weeks) | P for trend |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 (n=43) |

24 (n=114) |

25 (n=124) |

26 (n=169) |

27 (n=159) |

28 (n=196) |

29 (n=213) |

30 (n=262) |

31 (n=312) |

32 (n=451) |

33 (n=639) |

34 (n=1058) |

35 (n=1477) |

36 (n=3117) |

||

| Length of hospital stay, days | 11.0 (2.0– 120.0) | 74.5 (14.0– 110.0) | 88.0 (57.0– 103.5) | 78.0 (59.0– 100.0) | 66.0 (51.0– 85.0) | 58.0 (46.0–– 72.0) | 49.0 (39.0– 58.0) | 40.0 (31.0– 48.0) | 32.0 (24.5– 39.0) | 22.0 (17.0– 30.0) | 15.0 (11.0– 22.0) | 10.0 (6.0– 15.0) | 3.0 (2.0–7.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | <.001 |

| Change in median length of hospital stay, days* | − | 63.5 | 13.5 | −10.0 | −12.0 | −8.0 | −9.0 | −9.0 | −8.0 | −10.0 | −7.0 | −5.0 | −7.0 | 0 | |

| Length of hospital stay in survivors, days | 120.0 (51.0– 120.0) | 101.5 (58.0– 120.0) | 91.0 (73.0– 108.0) | 82.0 (66.0– 105.0) | 68.0 (59.0– 87.0) | 58.0 (47.0– 72.0) | 50.0 (40.0– 58.0) | 40.0 (32.0– 48.0) | 32.0 (25.0– 39.0) | 22.0 (17.0– 30.0) | 15.0 (11.0– 22.0) | 10.0 (6.0– 15.0) | 3.0 (2.0– 7.0) | 3.0 (2.0– 4.0) | <.001 |

| Post-menstrual age at discharge in survivors, weeks | 40.6 (39.4– 40.7) | 39.6 (37.9– 40.6) | 38.5 (37.1– 40.0) | 38.1 (36.6– 40.2) | 37.3 (36.1– 39.6) | 36.9 (35.6– 38.9) | 36.6 (35.4– 37.7) | 36.3 (35.3– 37.4) | 36.0 (35.1– 37.0) | 35.7 (35.0– 36.9) | 35.7 (35.0– 36.6) | 35.9 (35.3– 36.6) | 36.1 (35.9– 36.4) | 37.0 (36.7– 37.1) | <.001 |

| Length of hospital stay among deceased neonates, days | 1.0 (0.0– 5.0) | 5.5 (1.0– 21.5) | 16.0 (5.0– 25.0) | 10.0 (1.0– 18.0) | 2.0 (0.0– 14.0) | 18.0 (8.5– 28.0) | 6.0 (3.0– 7.5) | 9.0 (4.0– 13.0) | 7.0 (3.0– 11.0) | 1.0 (1.0– 1.0) | 5.0 (5.0– 5.0) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.47 |

median length in the current week minus median length of stay in the week preceding

We did not observe any temporal trends in neonatal death (p=.95 for trend) or major neonatal morbidity (p=.98 for trend) over the 3 year study period. There was a small decrease in the frequency of minor neonatal morbidity from study year 1 (39.6%) to year 3 (36.4%), p=.02 for trend.

Comment

Our data provide valuable information regarding a spectrum of neonatal outcomes for each week of completed pregnancy. This information may be useful when counseling patients regarding expected outcomes. Knowledge of risk and cause of death also may be useful for patient counseling. Clinical judgments have been shown, on average, to estimate lower survival probabilities than those supported by data.20,21 It has been observed that neonatologists with the correct estimation of neonatal survival intervene more often with appropriate invasive therapies, including mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, inotropes, and intravenous fluids, compared with clinicians who are not well informed regarding survival probabilities.22

The majority of prior studies examining delivery gestational age week-specific outcomes are not population based and many include cohorts that are now at least 5-10 years old, even if publication dates are more recent.23–25 Although this study includes a proportion of women who were transferred to academically affiliated centers for delivery at each gestational age, the study encompasses a wide range of social, demographic, and geographic diversity across the United States. Given the recent advances in maternal medicine (e.g., use of antenatal magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection), and neonatal medicine (e.g., shift from intubation and ventilator use towards continuous positive airway pressure oxygenation), mortality and morbidity may be overestimated in older studies, but it is difficult to truly ascertain when older studies are outdated. Stoll and colleagues recently found temporal changes in individual preterm morbidities in neonates delivered at each preterm gestational age between 2005–2012.6 Other more recent data focus on delivery gestational age epochs (e.g., very preterm, late preterm) and often do not provide week-specific gestational age outcomes. Although abundant, many studies of ‘late–preterm’ neonates have focused on mortality and morbidity differences between late-preterm and term infants. The presence of newer data does not invalidate older data per se, but as additional contemporary data incorporating modern management strategies is published, it adds to the body of evidence that can be used to counsel women and families regarding outcomes following PTB.

Our results were comparable to 8,877 neonates delivered 22–28 weeks of gestation between 2008–2012 and included in a recent Neonatal Research Network publication.6 The incidence of death in our cohort was lower to the incidence of death at each of the delivery gestational ages examined in the Neonatal Research Network data (44 vs. 68% at 23 weeks, 32 vs. 38% at 24 weeks, 12 vs. 23% at 25 weeks, 11 vs. 15% at 26 weeks, 8 vs. 10% at 27 weeks, 2 vs. 6% at 28 weeks), although the Neonatal Research Network included those with congenital anomalies which may account for some of the observed differences.6 We were unable to directly compare the incidence of major neonatal morbidity between cohorts given differing definitions of this composite outcome between studies, although trends were similar. In contrast to the Neonatal Network paper, we included neonates born at later gestational ages (through 36 weeks of gestation), and our focus was not on temporal trends in neonatal care or outcomes, but rather, more detailed obstetric and antenatal characteristics and the impact of such factors across the spectrum of preterm gestational ages. It is not unexpected that as the incidence of death and major morbidity fell, the incidence of minor morbidity rose, given our study design (neonates were classified by the worst outcome they met criteria for).

The cause of death among premature neonates is difficult to discern, and many neonates had no listed cause other than ‘extreme prematurity.’ Given that this is a study of preterm neonates, we chose not to report ‘extreme prematurity’ as a cause of death in our results since prematurity is a non-specific cause of death and arguably this was a contributing factor to all morbid outcomes in our study population of premature neonates. At the earliest gestational ages, variation in the use of active resuscitative treatment may have influenced some of the outcomes, as others have reported.26

It is notable that the frequency of delivery by cesarean among this cohort of pre-term neonates was high. At early gestational ages (24–31 weeks), between 58.3–67.9% of babies were delivered by cesarean; this may be partly explained by the high proportion of malpresentation (e.g., breech) among these very preterm neonates (21.8–55.7% were non-vertex at 24–31 weeks, Table 2). However, even when the proportion of neonates in the vertex presentation increased to 84% or greater at 32 weeks, the frequency of cesarean delivery remained high, as 37.9% of 36 week neonates were delivered by cesarean. Historically in the US, rates of cesarean delivery of non-anomalous singleton preterm neonates have varied widely (from 4.1% to 62%); unfortunately, differing patient populations and inclusion criteria limits comparisons between studies.6,27–29

The traditional counseling provided to women delivering prematurely is that they can expect their baby to be discharged ‘around the time of their due date’. This counseling held true in this cohort only for those babies delivered at the earliest gestational ages (23–26 weeks of gestation). Our findings at these early gestational ages were similar to the Neonatal Research Network Study reported by Stoll and colleagues.6 Surviving babies delivered at 27 weeks were discharged at a median 2.5 weeks prior to the maternal due date, whereas those delivered 31–35 weeks of gestation were discharged approximately 4 weeks prior to the maternal due date. The median post-menstrual age at discharge was noted to decrease with each additional week in utero, until it reached a nadir at 35.7 weeks of gestation for those delivered 32–33 weeks of gestation. Additionally, although significant advances have been made in perinatal and neonatal medicine, we found that babies born between 26 and 32 weeks of gestation spend 8–11 days longer in the hospital compared with those premature neonates remaining in utero for one additional week.

Our study had several strengths. Although all delivered at academically-affiliated hospitals, these data include neonates delivered at centers with significant heterogeneity regarding location, geographic region, hospital level of care, and patient socioeconomic status. Additionally, the inclusion criteria were broad, and the analysis did not exclude neonates delivered for a particular condition or indication. In contrast to other large multi-center studies examining neonatal outcomes, we included detailed antenatal and pregnancy characteristics. Thus, these results are widely applicable within the United States. This large dataset has the additional unique quality of being collected prospectively by trained research staff, ensuring high quality data. The presentation of week-specific outcome data provides concrete data with regards to anticipated outcomes and neonatal length of hospitalization when counseling patients.

Our study should be interpreted with limitations in mind. As described above, the underlying etiology of neonatal death was difficult to determine in many cases. This limitation is not unique to our study. Even with prospective data collection, the cause of death is often multifactorial and subjective. As with any secondary analysis, we were limited by data collected at the time of the original study; for example, we do not have information regarding pre-pregnancy BMI, and we do not have data regarding stillbirths or long-term morbidities. Generalizability may be limited to academic-affiliated medical centers.

In conclusion, we have presented contemporary neonatal outcome data across the spectrum of viable preterm gestational ages. These data suggest that the designations of ‘early preterm’ and ‘late preterm’ are somewhat artificial and arbitrary. Our data show that there is a continuum of outcomes, with each additional week for gestation conferring survival benefit while reducing the length of initial hospitalization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cynthia Milluzzi, R.N. (MetroHealth Medical Center-Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) and Joan Moss, R.N.C., M.S.N. (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX) for protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers; and Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D. (The George Washington University Biostatistics Center, Washington, DC), Brian M. Mercer, M.D. (MetroHealth Medical Center-Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH) and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D. (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD) for protocol development and oversight.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [HD21410, HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34208, HD36801, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, HD40485, HD53097, HD53118] and the National Center for Research Resources [UL1 RR024989; 5UL1 RR025764]. This study was also funded by the NICHD 5K23HD067224 (Dr. Manuck). Comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent views of the NICHD or NIH.

Appendix

In addition to the authors, other members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network are as follows:

University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, UT – M. Varner, K. Hill, A. Sowles, J. Postma (LDS Hospital), S. Alexander (LDS Hospital), G. Andersen (LDS Hospital), V. Scott (McKay-Dee), V. Morby (McKay-Dee), K. Jolley (UVRMC), J. Miller (UVRMC), B. Berg (UVRMC)

Columbia University, New York, NY – M. Talucci, M. Zylfijaj, Z. Reid (Drexel U.), R. Leed (Drexel U.), J. Benson (Christiana H.), S. Forester (Christiana H.), C. Kitto (Christiana H.), S. Davis (St. Peter's UH.), M. Falk (St. Peter's UH.), C. Perez (St. Peter's UH.)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC – K. Dorman, J. Mitchell, E. Kaluta, K. Clark (WakeMed), K. Spicer (WakeMed), S. Timlin (Rex), K. Wilson (Rex)

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX – K. Leveno, L. Moseley, M. Santillan, J. Price, K. Buentipo, V. Bludau, T. Thomas, L. Fay, C. Melton, J. Kingsbery, R. Benezue

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – H. Simhan, M. Bickus, D. Fischer, T. Kamon (deceased), D. DeAngelis

MetroHealth Medical Center-Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH – B. Mercer, C. Milluzzi, W. Dalton, T. Dotson, P. McDonald, C. Brezine, A. McGrail

The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH – C. Latimer, L. Guzzo (St. Ann's), F. Johnson, L. Gerwig (St. Ann's), S. Fyffe, D. Loux (St. Ann's), S. Frantz, D. Cline, S. Wylie, J. Iams

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL – M. Wallace, A. Northen, J. Grant, C. Colquitt, D. Rouse, W. Andrews

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL – G. Mallett, M. Ramos-Brinson, A. Roy, L. Stein, P. Campbell, C. Collins, N. Jackson, M. Dinsmoor (NorthShore University HealthSystem), J. Senka (NorthShore University HealthSystem), K. Paychek (NorthShore University HealthSystem), A. Peaceman

University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX – J. Moss, A. Salazar, A. Acosta, G. Hankins

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI – N. Hauff, L. Palmer, P. Lockhart, D. Driscoll, L. Wynn, C. Sudz, D. Dengate, C. Girard, S. Field

Brown University, Providence, RI – P. Breault, F. Smith, N. Annunziata, D. Allard, J. Silva, M. Gamage, J. Hunt, J. Tillinghast, N. Corcoran, M. Jimenez

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston-Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX – F. Ortiz, P. Givens, B. Rech, C. Moran, M. Hutchinson, Z. Spears, C. Carreno, B. Heaps, G. Zamora

Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR – J. Seguin, M. Rincon, J. Snyder, C. Farrar, E. Lairson, C. Bonino, W. Smith (Kaiser Permanente), K. Beach (Kaiser Permanente), S. Van Dyke (Kaiser Permanente), S. Butcher (Kaiser Permanente)

The George Washington University Biostatistics Center, Washington, DC – E. Thom, Y. Zhao, P. McGee, V. Momirova, R. Palugod, B. Reamer, M. Larsen, T. Spangler, A. Lozitska

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD – C. Spong, S. Tolivaisa

MFMU Network Steering Committee Chair (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) – J. P. VanDorsten, M.D.

Footnotes

Author Affiliation Notes:

Since the study was conducted, Dr. Manuck has moved to the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine (Chapel Hill, NC).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: Dr. Tracy Manuck serves on the scientific advisory board for Sera Prognostics, a private company that was established to create a commercial test to predict preterm birth and other obstetric complications. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

PRESENTATION: Presented in part at the Society for Reproductive Investigation Annual Meeting on March 28, 2015 (San Francisco, CA) as an oral concurrent presentation (final Abstract ID O-131).

REPRINTS will not be available.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Neonatal mortality and morbidity rates in late preterm births compared with births at term. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:35–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297311.33046.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Incidence of and risk factors for neonatal morbidity after active perinatal care: extremely preterm infants study in Sweden (EXPRESS) Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:978–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Kinney M. Preterm birth: now the leading cause of child death worldwide. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:263ed21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, et al. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1995 through December 1996. NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iams JD, Romero R, Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. Primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions to reduce the morbidity and mortality of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:164–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in Care Practices, Morbidity, and Mortality of Extremely Preterm Neonates, 1993–2012. Jama. 2015;314:1039–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkola K, Ritari N, Tommiska V, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age of a national cohort of extremely low birth weight infants who were born in 1996–1997. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1391–400. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, et al. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;196:147e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson DK, Wright LL, Lemons JA, et al. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, January 1993 through December 1994. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1998;179:1632–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Lackritz EM. Epidemiology of late and moderate preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moutquin JM. Classification and heterogeneity of preterm birth. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2003;110(Suppl 20):30–3. doi: 10.1016/s1470-0328(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kallankari H, Kaukola T, Olsen P, Ojaniemi M, Hallman M. Very preterm birth and foetal growth restriction are associated with specific cognitive deficits in children attending mainstream school. Acta paediatrica. 2014 doi: 10.1111/apa.12811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:262–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron IS, Litman FR, Ahronovich MD, Baker R. Late preterm birth: a review of medical and neuropsychological childhood outcomes. Neuropsychology review. 2012;22:438–50. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chyi LJ, Lee HC, Hintz SR, Gould JB, Sutcliffe TL. School outcomes of late preterm infants: special needs and challenges for infants born at 32 to 36 weeks gestation. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;153:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitsommart R, Janes M, Mahajan V, et al. Outcomes of late-preterm infants: a retrospective, single-center, Canadian study. Clinical pediatrics. 2009;48:844–50. doi: 10.1177/0009922809340432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nepomnyaschy L, Hegyi T, Ostfeld BM, Reichman NE. Developmental outcomes of late-preterm infants at 2 and 4 years. Maternal and child health journal. 2012;16:1612–24. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0853-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Can differences in obstetric outcomes be explained by differences in the care provided? The MFMU Network APEX study American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;211:147e1–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Rice MM, et al. Risk-adjusted models for adverse obstetric outcomes and variation in risk-adjusted outcomes across hospitals. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;209:446e1–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morse SB, Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Estimation of neonatal outcome and perinatal therapy use. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1046–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanco F, Suresh G, Howard D, Soll RF. Ensuring accurate knowledge of prematurity outcomes for prenatal counseling. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e478–87. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haywood JL, Morse SB, Goldenberg RL, Bronstein J, Nelson KG, Carlo WA. Estimation of outcome and restriction of interventions in neonates. Pediatrics. 1998;102:e20. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.2.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, et al. Intensive care for extreme prematurity--moving beyond gestational age. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:1672–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeitlin J, Draper ES, Kollee L, et al. Differences in rates and short-term outcome of live births before 32 weeks of gestation in Europe in 2003: results from the MOSAIC cohort. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e936–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Group E, Fellman V, Hellstrom-Westas L, et al. One-year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. Jama. 2009;301:2225–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1801–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deulofeut R, Sola A, Lee B, Buchter S, Rahman M, Rogido M. The impact of vaginal delivery in premature infants weighing less than 1,251 grams. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:525–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154156.51578.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wylie BJ, Davidson LL, Batra M, Reed SD. Method of delivery and neonatal outcome in very low-birthweight vertex-presenting fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:640e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.038. discussion e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner EF, Han CS, Savitz DA, Goldshore M, Lipkind HS. Health outcomes for vaginal compared with cesarean delivery of appropriately grown preterm neonates. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;121:1195–200. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182918a7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]