Abstract

Although it is widely accepted that discrimination is associated with heavy and hazardous drinking, particularly within stress and coping frameworks, there has been no comprehensive review of the evidence. In response, we conducted a systematic review of the English language peer-reviewed literature to summarize studies of discrimination and alcohol-related outcomes, broadly defined. Searching six online data bases, we identified 937 non-duplicative titles published between 1980 and 2015, of which 97 met all inclusion criteria for our review and reported quantitative tests of associations between discrimination and alcohol use. We extracted key study characteristics and assessed quality based on reported methodological details. Papers generally supported a positive association; however, the quantity and quality of evidence varied considerably. The largest number of studies was of racial/ethnic discrimination among African Americans in the United States, followed by sexual orientation and gender discrimination. Studies of racial/ethnic discrimination were notable for their frequent use of complex modeling (i.e., mediation, moderation) but focused nearly exclusively on interpersonal discrimination. In contrast, studies of sexual orientation discrimination (i.e., heterosexism, homophobia) examined both internalized and interpersonal aspects; however, the literature largely relied on global tests of association using cross-sectional data. Some populations (e.g., Native Americans, Asian and Pacific Islanders) and types of discrimination (e.g., systemic/structural racism; ageism) received scant attention. This review extends our knowledge of a key social determinant of health through alcohol use. We identified gaps in the evidence base and suggest directions for future research related to discrimination and alcohol misuse.

Keywords: Racism, sexism, homophobia, binge drinking, alcohol use disorders

Background

From the late 1980s onward, studies began reporting an association between racism and poorer cardiovascular health among African Americans in the United States (Armstead, Lawler, Gorden, Cross, & Gibbons, 1989; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; McNeilly et al., 1995). Over subsequent decades, researchers across multiple disciplines extended this initial observation, finding associations between discrimination and negative health outcomes in a variety of populations. With recent, growing recognition of health inequities, discrimination has been identified as a social mechanism responsible, at least in part, for observed health disparities among minority groups (Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, 2008; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, ND).

Several theories suggest that discrimination should be associated with alcohol use. For example, the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) has been widely used as an organizing heuristic in studies of heavy and hazardous drinking. Although the Transactional Model does not identify specific stressors, it may be self-evident that discrimination would be experienced as a stressor. Extending the basic framework, Minority Stress Models (R. Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999; Harrell, 2000; Meyer, 2003), which posit that members of minority groups will experience excess stress related to their minority status (i.e., above and beyond what is otherwise expected), have identified discrimination as a specific risk exposure. Most recently, the Social Resistance Framework (Factor, Kawachi, & Williams, 2011) suggests that minorities may engage in health compromising behaviors, such as substance use, as conscious or unconscious acts of resistance against a majority group. Specifically, the social forces responsible for majority-minority distinctions, including experiences of discrimination, may trigger alienation or lack of attachment to the dominant culture, which in turn could lead to behaviors in opposition to dominant norms. In each of these theoretical frameworks, discrimination may be associated with mal-adaptive coping responses, including heavy drinking.

As studies of discrimination and health outcomes have accumulated, a number of previous reviews have attempted to make sense of the literature. In 1999, Krieger (1999) published the first review, arguing for the importance of an epidemiological analysis of discrimination, outlining key methods, and summarizing the early evidence. Among 20 papers dealing predominantly with racial/ethnic discrimination, a wide variety of physical and mental health outcomes were studied; however, alcohol use was absent. Following closely in 2000, Williams and Williams-Morris (2000) reviewed 15 studies of mental health outcomes in community samples, devoting considerable attention to conceptualizing how discrimination might operate and proposing future areas of research. The papers included in that review reported associations between racial/ethnic discrimination and psychological distress, depression, and anxiety. Yet again, no study examined alcohol use. Shortly thereafter, Williams and colleagues (2003) conducted a subsequent review that included physical, mental, and behavioral health outcomes. Of 86 studies examined, only two examined alcohol use, both finding a positive association with discrimination; however, important details were lacking. For example, hazardous drinking was not distinguished from any alcohol use, and the review excluded studies done with college students, a priority population for alcohol research. That same year, two additional reviews appeared, both focused on the relationship between racial/ethnic discrimination and cardiovascular outcomes (Brondolo, Rieppi, Kelly, & Gerin, 2003; Wyatt et al., 2003). These papers reflected the state of US health disparities research, which was driven by growing recognition of stark inequities among African Americans. Consistent with other reviews, both papers devoted considerable attention to potential mechanisms through which discrimination might exert an effect on health; however, the narrow focus on cardiovascular disease did little to extend substance abuse research.

The first systematic review appeared in 2006, in which Paradies (2006) continued the focus on racial/ethnic discrimination as the risk exposure but extended the sample to include studies with a variety of health outcomes. Of 138 studies reviewed, 14 addressed alcohol use, presenting mixed findings. Eight found positive associations but six reported no association. Despite a more rigorous approach than previous reviews, important details were lacking. Notably, hazardous drinking was not distinguished from any alcohol use. Subsequently, Pascoe and Richman (2009) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 papers. Among the review’s strengths, it included multiple forms of discrimination and proposed a conceptual model of the relationship between discrimination and mental and physical health outcomes. Alcohol was included as a search term, however, it was collapsed with tobacco use and illicit drug use to model the latent construct of health damaging coping behaviors, thus obscuring the relationship between discrimination and drinking. Most recently, Paradies and colleagues (2015) reviewed 333 papers, representing the most ambitious summary to date. They conducted a meta-analysis of racial ethnic discrimination on general, physical, and mental health outcomes. Although the study described in detail the inverse relationship between racism and health, it did not include substance use as a potential outcome. Thus, it did little to advance our understanding of the relationship between discrimination and alcohol-related outcomes.

Although a positive association with alcohol use is widely accepted, particularly within stress and coping frameworks, there have been few attempts to assess its support. Previous reviews have combined drinking with other substance use or neglected to examine it at all. Thus, the degree to which our received wisdom corresponds to empirical findings remains unknown. Compounding the challenge, multiple drinking outcomes have been studied, ranging from any alcohol consumption to various types of hazardous drinking, such as binge episodes (defined as four/five or more drinks on a single occasion for women and men, respectively), drinking-related problems (e.g., failure to fulfill work, family, or social obligations), and symptoms of dependence (e.g., craving, tolerance, delirium tremens). Seeking a rigorous assessment of the evidence, we conducted a systematic review to summarize empirical findings about discrimination and alcohol-related outcomes, broadly defined. Additionally, we assessed characteristics of studies, such as the types of discrimination studied, measures used, sampling methods, and analytic strategies, among others. In effect, this review sought to provide both a summary of the evidence (i.e., what is known) and an overview of methods (i.e., how that knowledge was produced).

Methods

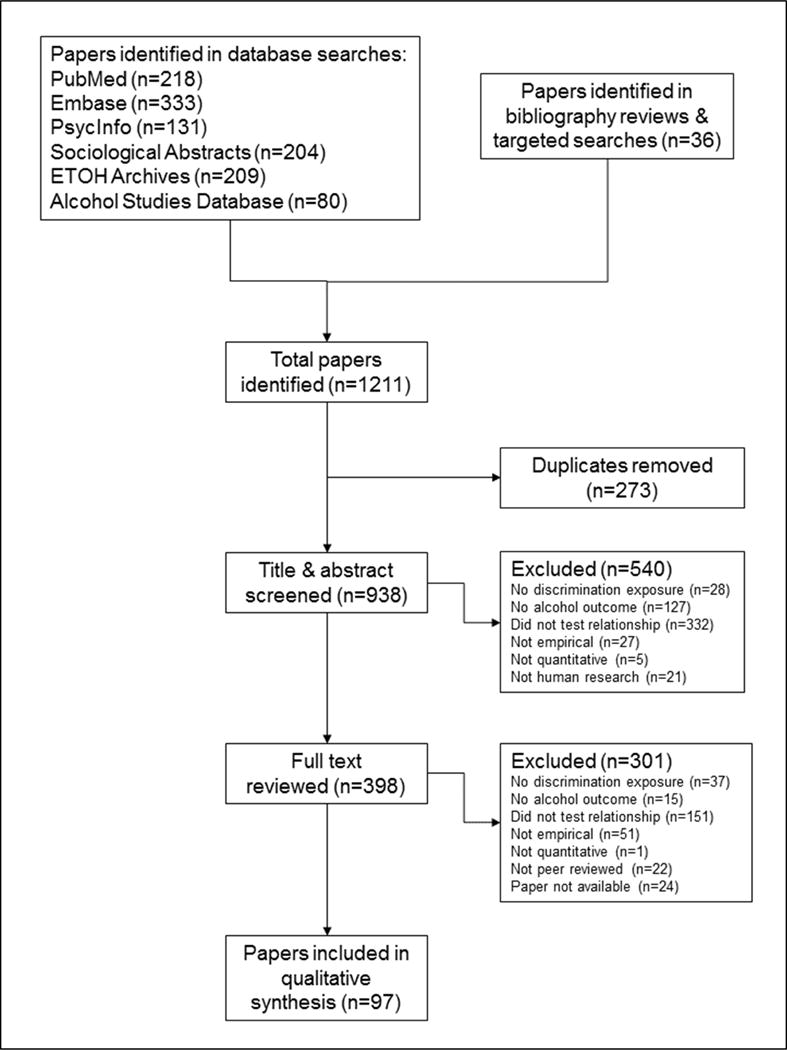

We utilized standard procedures for systematic reviews (Egger, Smith, & Altman, 2001; Glasziou, 2001), following the PRISMA guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/Default.aspx) and registering this project in the PROSPERO database (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero). As it did not constitute human subjects research, ethics board approval was not required. We searched six online databases (e.g., PubMed) using combinations of controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms such as “alcohol-related disorders”) and free text to identify potentially relevant papers (search details in Appendix A). Following Jones’ typology (2000), we accepted studies of discrimination at multiple social-ecological levels, such as systemic/structural, interpersonal, and internalized discrimination. To be included in this review, papers must have reported quantitative findings in a peer-reviewed journal between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2015. Qualitative and non-empirical works, such as commentaries or book reviews, were excluded. Likewise, manuscripts that had not undergone peer review, such as dissertations or conference abstracts, were not included. After removing duplicate citations, we screened titles and abstracts, excluding papers if they did not report findings from human research, if discrimination was not a risk exposure, if there was no alcohol outcome, if the paper did not test the relationship between discrimination and an alcohol-related outcome, or if the paper was not written in English. Next, the full text of eligible papers was retrieved for a second, detailed review to confirm eligibility. Screenings were completed by the first author and a research assistant. Periodic reliability checks of sub-sets of papers that included the second author showed almost perfect agreement among screeners (all κ>.90). Any discrepancy about inclusion of papers was resolved through discussion of each case. We reviewed bibliographies and conducted several targeted searches by investigator name to identify other potential papers. Of 938 non-duplicative titles, 398 were retrieved for full text review, of which 97 met all inclusion criteria and were included in this analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature search and review process

Key study characteristics were identified using a data extraction form and entered into a spreadsheet for analysis by the first author and a research assistant. If papers included sequential or hierarchical models, we took findings from the final, fully adjusted model. We derived a quality index from six characteristics (study design, sampling strategy, use of established measures for the exposure and outcome, appropriate analytic procedures, and attention to threats to internal validity) categorizing papers as low, moderately good, or high quality. We analyzed the extracted data by discrimination type, looking for patterns and themes across studies using matrix displays, a common data reduction technique in qualitative research (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Because of the great heterogeneity of study designs, populations, and measures, we did not perform a meta-analysis.

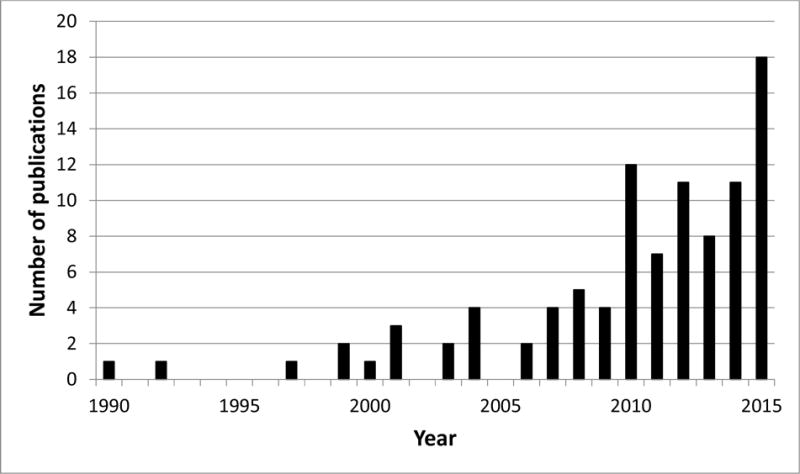

The 97 papers included in this review represented 82 parent studies. This analysis focused on individual papers, rather than parent studies, because papers examined different research questions, outcomes, or sub-groups, thereby contributing distinct findings despite sometimes utilizing a common data set. Key characteristics of the papers are shown in Table 1. Although our literature search time frame began in 1980, the sample was largely comprised of recently published work (Figure 2). For example, we found no papers that met all eligibility criteria that had been published prior to 1990, and the majority (69%) included in this review was published in 2010 or later.

Table 1.

Characteristics of papers (n=97) reporting findings on discrimination and alcohol outcomes, 1980–2015.

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Discrimination type | ||

| Racial/ethnic | 68 | (70) |

| Sexual orientation | 16 | (16) |

| Gender | 3 | (3) |

| Age | 1 | (1) |

| Multiple/generalized | 9 | (9) |

| Theoretical or conceptual foundation | ||

| Explicit | 28 | (29) |

| Implied | 10 | (10) |

| None | 59 | (61) |

| Study design | ||

| Cross-sectional | 78 | (80) |

| Longitudinal | 17 | (18) |

| Experiment | 2 | (2) |

| Sampling strategy | ||

| Probability | 47 | (48) |

| Non-probability | 46 | (47) |

| Not reported | 4 | (4) |

| Sample size | ||

| <100 | 3 | (3) |

| 100–499 | 35 | (36) |

| 500–999 | 18 | (19) |

| 1000–4999 | 30 | (31) |

| ≥5000 | 11 | (11) |

| Study setting | ||

| US | 87 | (90) |

| Non-US | 8 | (8) |

| Not reported | 2 | (2) |

| Study scope | ||

| National | 29 | (30) |

| State/province/region | 30 | (31) |

| City/community | 36 | (37) |

| Not reported | 2 | (2) |

| Quality index | ||

| Low | 26 | (27) |

| Moderate | 60 | (62) |

| High | 11 | (11) |

Figure 2.

Number of publications examining discrimination and alcohol outcomes by year

Results

Racial/Ethnic Discrimination

Seventy-one papers reported findings about racial/ethnic discrimination, making it the most frequently studied topic and constituting the majority of papers included in this review. Nearly all papers were based in the United States, but one each reported findings from Brazil, Canada, Hong Kong, and New Zealand. Studies examined a wide variety of outcomes, sometimes reporting multiple findings in a single paper. Alcohol-related outcomes included any drinking, hazardous drinking patterns (e.g., binge episodes), negative consequences of drinking, and symptoms of dependence. Nearly half of these papers (n=31, 44%) reported global tests of associations whereas more than half (n=45, 63%) used complex analytic strategies (e.g.,mediation, moderation). Six papers included both global tests and more complex analyses. Table 2 summarizes findings on racial/ethnic discrimination by type of test.

Table 2.

Racial/ethnic discrimination and alcohol outcomes: a summary of findings by type of test, 1980–2015.

| Study | Sample | Design | Discrimination level | Alcohol-related outcome(s) | Key Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests of global associations | |||||

| Blume et al. (2012) | 594 college students in US Southeast state | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 2 week binge drinking | Positive association |

| Boynton et al. (2014) | 619 African American young adults in US mid-Atlantic region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Number of drinks in a typical month | No association |

| Broman (2007) | 1,587 college students in US Midwest state | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 30 day alcohol use & binge drinking; past 2 month weekend drinking; drinking-related problems | Positive associations |

| Caldwell et al. (2013) | 332 African American adult men from two cities in US Midwest region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use | No association |

| Cano et al. (2015) a | 129 Latino young adult college students in US (location not specified) | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year hazardous drinking | Positive association |

| Cano et al. (2015) b | 302 Latino adolescents in Los Angeles CA & Miami FL | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses baseline wave) | Interpersonal & systemic/structural | Past 90 day binge drinking | No association for systemic/structural discrimination; positive association for interpersonal discrimination |

| Chavez et al. (2015) | 69,857 adults who reported past year employment in 15 US states | Repeated cross-sectional (analytic sample collapses seven waves) | Interpersonal | Past month alcohol use, heavy drinking, and binge drinking | No association with alcohol use or binge drinking; positive association with heavy drinking |

| Cheadle & Whitbeck (2011) | 727 Native American adolescents in US Midwest and Canada | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses five waves) | Interpersonal | Drinking debut; alcohol use disorder | Positive associations |

| Chen et al. (2014) | 113 Asian/Pacific Islander college students in US Southwest | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use; past six month drinking-related problems | None: outcomes too infrequent to permit modelling |

| Cook et al. (2012) | 952 Asian & Pacific Islander adults from US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use, drinking frequency, total volume consumed | No associations |

| Crengle et al.(2012) | 9,080 multiethnic adolescents in New Zealand national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past four-week binge episodes | Positive association |

| Factor et al. (2013) | 400 African American and White adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past month quantity of drinks consumed | Positive association |

| Gilbert et al. (2014) | 190 Latino men who have sex with men in North Carolina | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use | Positive association |

| Goldbach et al. (2015) | 901 Latino adolescents in Los Angeles CA, Miami FL, El Paso TX, Lawrence MA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past month alcohol use | No association |

| Grekin (2012) | 283 African American & White college students at urban university in US Midwest | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses one wave) | Interpersonal | Past three month alcohol use | No association |

| Hunte & Barry (2012) | 5,008 African American adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | Positive association |

| Hurd et al. (2014) | 607 African American young adults in US Midwest city (not specified) | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses four waves) | Interpersonal | Past 30 day alcohol use | Positive association |

| Kulis et al. (2009) | 1,374 Latino children and adolescents in Phoenix AZ | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 30 day alcohol use | Positive association |

| Kwate et al. (2010) | 139 adult African American women in New York NY | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal & systemic/structural | Binge drinking; hazardous drinking | No associations with systemic/structural discrimination; positive associations with interpersonal discrimination |

| Martin et al. (2003) | 1,531 African American adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal & systemic/structural | Hazardous drinking; escapist drinking motives | No association with systemic/structural discrimination; positive association with interpersonal discrimination |

| Okamoto et al. (2009) | 1332 Latino adolescents in California | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime & past 30 day alcohol use; past 30 day binge drinking | Positive associations |

| O’Hara et al. (2015) | 441 African American current drinking college students at a single US institution | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses 30 days of daily diaries) | Interpersonal | Daily alcohol use | No association |

| Ornelas et al. (2015) | 5,313 Latinos in Bronx NY, Chicago IL, Miami FL, San Diego CA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime binge drinking | No association |

| Otiniano Verissimo et al. (2014) | 2,312 Latino adults in US national | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | No association |

| Respress et al. (2013) | 2,427 African American & White adolescents in US national sample | Longitudinal (analytic sample uses one wave) | Interpersonal | Past year binge drinking | No association |

| Savage & Mezuk (2014) | 4,649 Latino & Asian American adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | Positive association |

| Taylor & Jackson (1990) | 289 African American women in a US city (not specified) | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past week alcohol quantity | Positive association |

| Terrell et al. (2006) | 134 African American adolescents in Texas | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Weekly alcohol quantity; hazardous drinking | No association with hazardous drinking; positive association with weekly quantity |

| Tobler et al. (2013) | 2490 White, African American, and Latino adolescents in Chicago IL | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 30 day drinking frequency; past 30 day binge drinking frequency | No association |

| Torres & Vallejo (2015) | 244 Latino adults in a US Midwest city (not specified) | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | No association with source of discrimination; positive association with reaction to discrimination |

| Unger et al. (2014) | 2722 Latino adolescents in California | Longitudinal cohort (analytic samples uses four waves) | Interpersonal | Past month alcohol use (any vs. none) | Positive association with intercept but not slope in growth curve models |

| Yoo et al.(2010) | 1531 Asian Americans in Arizona | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | “Current” alcohol use (any vs. none) | Positive association |

| Tests of mediated associations | |||||

| Acosta et al. (2015) | 371 substance using Latino adolescents in Miami FL | Experiment (analytic sample uses baseline wave) | Interpersonal | Past 30 day drinking frequency & quantity | Negative association with peer affiliation, which in turn has negative association with drinking frequency & quantity |

| Boynton et al. (2014) | 619 African American young adults in US Mid-Atlantic region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Drinking-related problems | Positive association through depression among women and through depression and anger among men. |

| Brody et al. (2012) | 538 African American adolescents in Georgia | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Past month substance use† | Positive association through school engagement and peers’ substance use |

| Flores et al. (2010) | 110 Latino adolescents in California | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Alcohol use | Positive association through post-traumatic stress symptoms |

| Gibbons et al. (2004) | 779 African American adolescent-parent dyads in Georgia & Iowa | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Past year substance use† | Positive association through distress and friends’ use among adolescents; positive association through distress among parents |

| Gibbons et al. (2010) | 767 African American adolescent-parent dyads in Georgia & Iowa | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Substance use† | Positive association through anger and willingness to use among adolescents; positive association through hostility among parents |

| Gibbons et al. (2014) | 680 African American adult women in Georgia & Iowa | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Drinking-related problems | Positive association through anger/hostility |

| Mulia & Zemore (2012) | 4,080 adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol use disorder | Positive association through depressive symptoms & heavy drinking |

| Rodriguez-Seijas et al. (2015) | 5,191 African American adults in US national | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | Positive association through internalizing and externalizing symptoms |

| Schwartz et al. (2012) | 302 Latino adolescent-parent dyads in Los Angeles CA & Miami FL | Longitudinal | Interpersonal & systemic/structural | Past 90 day alcohol use, drunkenness, & binge drinking | No associations with alcohol use for interpersonal discrimination; positive associations with drunkenness and binge drinking for systemic/structural discrimination through decreased parent-adolescent communication |

| Tse & Wong (2015) | 202 South Asian adult men living in Hong Kong | Cross-section | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | Positive association through coping and enhancement drinking motives |

| Whitbeck et al. (2001) | 195 American Indian children & adolescents in US Midwest region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking; drinking-related problems | Positive association through anger & delinquent behavior |

| Whitbeck et al. (2004) | 452 American Indian adults in US Midwest region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 12 month alcohol abuse | Positive association through historical loss among men; positive association through historical loss & enculturation among women |

| Tests of conditional associations | |||||

| Bennett et al. (2010) | 4,454 women in Philadelphia PA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past 12 month alcohol use | No association for major discriminatory events; positive association for everyday discrimination; |

| Blume et al. (2012) | 594 college students in US Southeast state | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Drinking-related problems | Coping self-efficacy attenuated the positive association |

| Borrell et al. (2007) | 6,680 White & African American adults in Birmingham AL, Chicago IL, Minneapolis MN, Oakland CA | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use | No association if experiencing <3 domains of discrimination; positive association if experiencing ≥3 domains of discrimination; |

| Borrell et al. (2010) | 6,680 African American, Chinese American, Latino, and White adults age ≥45 in Birmingham AL, Chicago IL, Forsyth County NC, Minneapolis MN, Oakland CA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past month maximum quantity consumed in a day | No association among Latinos & Whites; positive association among African Americans & Chinese Americans; |

| Brodish et al. (2011) | 815 African American young adults in Maryland | Longitudinal | Interpersonal | Substance use† | Positive association among men; no association among women |

| Brody et al. (2012) | 347 African American adolescents in Georgia | Experiment | Interpersonal | Past 3 month alcohol use; Past 6 month substance use-related problems | Positive association with both outcomes through risk taking; associations attenuated by intervention condition |

| Brown et al. (2014) | 3,296 adolescents in Toronto Canada | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | “weekly drinking” | No association for verbal abuse; positive association for physical abuse |

| Bucchianeri et al. (2014) | 2,793 adolescents in Minneapolis & St. Paul MN | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use | No association among girls; positive association among boys |

| Chae et al. (2008) | 2,073 Asian American adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | No association at high levels of ethnic group identification; positive association at low levels of ethnic group identification; |

| Chavez et al. (2015) | 69,857 adults who reported past year employment in 15 US states | Repeated cross-sectional surveys (analytic sample uses 7 waves) | Interpersonal | Past month alcohol use, heavy drinking, and binge drinking | Positive association with heavy drinking and binge drinking among Latinos; no associations among other racial/ethnic groups |

| Clark et al. (2015) | 4,462 African American and Carribean Black adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | Positive association varies by patterns of discrimination experiences |

| Cook et al. (2012) | 952 Asian & Pacific Islander adults from US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year binge drinking | No association among foreign-born; negative association among US-born; |

| Gee at al. (2007) | 2,271 Asian Americans in San Francisco CA & Honolulu HI | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol use disorder | No association for past 12 month unfair events; positive association for past 30 day unfair treatment |

| Gilbert et al. (2014) | 190 Latino men who have sex with men in North Carolina | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past month binge drinking frequency | Positive association at low levels of social support |

| Gray & Montgomery (2012) | 168 African American & Latina adolescent women in US Southeastern city | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol use disorder | Positive association through post-traumatic stress symptoms |

| Grekin (2012) | 283 African American & White college students at urban university in US Midwest | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses one wave) | Interpersonal | Drinking-related consequences | Stronger between racism frequency and drinking-related consequences for African Americans than Whites |

| Kam et al. (2015) | 247 Latino children and adolescents in Illinois | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses three waves) | Interpersonal | Past three month alcohol use | No association when mother-child communication is high; positive association through depressive symptoms when mother-child communication is low; |

| Kim & Spencer (2011) | 1,443 Asian Americans in San Francisco CA & Honolulu HI | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year heavy drinking | No association among foreign-born; positive association among US-born |

| Latzman et al. (2013) | 336 current drinking African American and Asian American college students at 1 university in US Southeast | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Drinking-related problems | Positive association exacerbated by impulsivity (lack of premeditation) |

| Madkour et al. (2015) | 657 African American young adults in US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic samples uses four waves) | Interpersonal | Past year binge drinking frequency | Positive association varies by age (association at age 21 but not at other ages) |

| McCabe et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses 1 wave) | Interpersonal | Past year substance use disorder† | No association with past year discrimination; positive association with lifetime discrimination |

| McCord & Ensminger (1997) | 953 African American adults in Chicago | Longitudinal cohort | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use disorder | No association among women; positive association among men; |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses 1 wave) | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) | Positive association among African Americans; marginal association among Latinos |

| Nakashima & Wong (2000) | 2,306 White & Korean American adults in California | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol misuse‡ | No association among Korean Americans; negative association among Whites |

| Ornelas & Hong (2012) | 2,554 Latino & Asian American adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime substance use disorder† | Positive association among men; positive association among women only at highest level of discrimination |

| Otiniano Verissimo et al. (2013) | 401 Latino young adults in New York NY | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year substance use† | Positive association among women; negative association among men |

| Otiniano Verissimo et al. (2014) | 6,294 Latinos from US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year substance use disorder† | Positive association varied by gender and country of origin/descent |

| Tran et al. (2010) | 1,387 foreign-born adults in on county in Minnesota | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past month alcohol use; past month binge drinking | Positive association with alcohol use for Latino & African immigrants; positive association with binge drinking for Latino immigrants |

| Verney & Kipp (2008) | 42 White & Latino veteran in New Mexico | Cross-sectional | Systemic/structural | Alcohol use | No association among Latino veterans; positive association among White veterans |

| Walsemann & Bell (2010) | 6,889 African American & White adolescents | Longitudinal (analytic sample uses baseline wave) | Systemic/structural | Past year substance use† | No association among boys; positive association attenuated by Black race among girls |

| Yen et al. (1999) | 836 adult transit operators in San Francisco CA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol use; hazardous drinking; drinking-related problems | No association with drinking-related problems; positive associations with alcohol use and hazardous drinking if discrimination in ≥5 domains |

| Zemore et al. (2011) | 1,270 African American & Latino adults in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Systemic/structural & interpersonal | Heavy drinking; drinking-related problems; dependence symptoms | Positive associations that vary in strength by racial/ethnic group and are exacerbated by poverty and foreign nativity |

Composite measure that combined alcohol with tobacco and/or illicit drug use

Composite measure that combined heavy drinking with drinking-related problems

Global tests of association produced considerable inconsistent findings. Of 31 papers reporting a global test, 14 (45%) found a positive association, 10 (32%) found no association, and seven (23%) had mixed results (i.e., positive association for one outcome or exposure but no association for another outcome or exposure). For example, Okamoto and colleagues (2009) found that discrimination was associated with 63% higher odds of past month drinking among Latino adolescents. In contrast, Tobler and colleagues (2013) found no such association in a diverse sample of adolescents. The variability of findings may be a function of methods. Most papers were classified as moderate quality (n=16, 52%) or low quality (n=10, 32%), due to a reliance on cross-sectional data (n=26, 84%), non-probability sampling (n=17, 55%), and lack of an explicit theoretical foundation (n=16, 52%).

The larger body of findings from complex analyses showed not only more consistent positive associations, but also contributed further details about mechanisms. In mediational analyses, intervening variables were predominantly individual-level factors. For example, several studies found that racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with anger, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and depressive symptoms, which in turn were associated with alcohol abuse or dependence (Gray & Montgomery, 2012; Mulia & Zemore, 2012; Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, & Adams, 2004). As above, few studies examined mediators at social-ecological levels beyond the individual level. Among exceptions, peers’ substance use and collective historical loss were found to partially explain the relationships between racial/ethnic discrimination and adolescent substance use and adults’ risk of abuse or dependence, respectively (Brody, Kogan, & Chen, 2012; Whitbeck et al., 2004). The majority of papers reporting tests of mediation were of moderately good quality (n=10, 77%) due to greater use of longitudinal data (n=6, 46%), probability sampling (n=8, 62%), and explicit theoretical frameworks (n=6, 46%).

There were numerous tests of conditional relationships; however, it was often unclear how moderators were selected. Of 32 papers testing conditional associations, the majority (n=24, 75%) reported no theoretical framework for the study. Nevertheless, greater proportions of this set of papers were classified as high quality (n=6, 19%) or moderately good quality (n=19, 59%) due to use of probability sampling (n=19, 59%) and established discrimination measures (n=21, 66%). Moderation analyses identified differential effects of discrimination and clarified the conditions under which such associations occur. For example, two analyses found that the relationship between racial/ethnic discrimination and alcohol abuse or dependence varied by level of ethnic identity, such that higher levels of ethnic identity appeared to attenuate the association (Chae et al., 2008; L. S. Richman, Boynton, Costanzo, & Banas, 2013).

Overall, the scope of these studies was largely local, with most samples drawn from city (n=24, 34%) or state/regional (n=26, 37%) populations. More than half of the papers (63%) reported findings from a single racial/ethnic group, most often African Americans (n=18) and US Latinos (n=17). The majority of studies (n=48, 68%) used an established measure of the exposure, most frequently the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), followed by the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine, Klonoff, Corral, Fernandez, & Roesch, 2006), and the Experiences of Discrimination scale (Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005). Broad conclusions about racial/ethnic discrimination are difficult given the diversity of outcomes, analytic approaches, and populations studied; however, the preponderance of evidence supports a positive association, with inconsistently detailed evidence for some groups.

Sexual Orientation Discrimination

The second most frequently studied topic was discrimination due to sexual orientation (i.e., homophobia; heterosexism). Of 18 papers identified, the majority (n=15, 83%) was from the United States, but the set also included reports from Canada, Mexico, and the United Kingdom. As with racial/ethnic discrimination, these papers examined a wide variety of alcohol-related outcomes, and three papers contributed multiple findings. Table 3 summarizes findings on sexual orientation discrimination by type of test.

Table 3.

Sexual orientation discrimination and alcohol outcomes: a summary of findings by type of test, 1980–2015.

| Study | Sample | Design | Discrimination level | Alcohol-related outcome(s) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests of global associations | |||||

| Amadio & Chung (2004) | 207 sexual minority adults in Atlanta GA | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past month alcohol use; quantity consumed on drinking days; drinking-related problems | No association |

| Amadio (2006) | 335 sexual minority adults in US southern region | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past 30 day drinking quantity and frequency | No association |

| D’Augelli et al. (2001) | 416 sexual minority older adults in US and Canada | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Hazardous drinking | No association |

| Gilbert et al. (2014) | 190 sexual minority adult Latino men in North Carolina | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use; past 30 day binge drinking | No association |

| Hequembourg & Dearing (2013) | 389 sexual minority adults in Buffalo NY | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past year hazardous drinking | Positive association |

| Igartua et al. (2003) | 197 sexual minority adults in Montreal Canada | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Hazardous drinking | No association |

| Lehavot & Simoni (2011) | 1,381 sexual minority adult women in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Internalized & interpersonal | Current substance use† | Positive association |

| Livingston et al. (2015) | 704 sexual minority adolescents in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Internalized & interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | Positive association for internalized heterosexism; no association for interpersonal discrimination |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample, of whom 577 sexual minority adults | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) | No association |

| Rivers (2004) | 119 sexual minority adults in UK national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Alcohol use | No association |

| Rosario et al(2008) | 76 sexual minority adolescent and adult women in New York NY | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses baseline wave) | Internalized | Past three month drinking quantity and frequency | No association |

| Ross et al. (2001) | 422 sexual minority adult men in US Midwest region | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Hazardous drinking | No association |

| Wong et al. (2010) | 526 sexual minority young adult men in Los Angeles CA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | No association |

| Tests of mediated associations | |||||

| Huebner et al. (2015) | 504 sexual minority adolescents in Boston MA, Indianapolis IN, & Philadelphia PA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year substance use† | Positive association through affiliation with deviant peers |

| Lehavot & Simoni (2011) | 1,381 sexual minority adult women in US national sample | Cross-sectional | Internalized & interpersonal | Current substance use† | Positive association through decreased psychosocial resources |

| Ortiz-Hernandez et al. (2009) | 12,796 adolescents and young adults in Mexico national sample | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Lifetime alcohol use; current alcohol use; current heavy drinking | Discrimination partly explained positive association between same-sex attraction or LGB identity and lifetime alcohol use |

| Tests of conditional associations | |||||

| Amadio & Chung (2004) | 207 sexual minority adults in Atlanta GA | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Lifetime alcohol use | Negative association among women; no association among men |

| Amadio (2006) | 335 sexual minority adults in US southern region | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past 30 day binge drinking; drinking-related problems | Positive association among women; no association among men |

| Austin & Irwin (2010) | 1,141 sexual minority adult women in US southern region | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | Positive association among women less than age 50 years; no association at age 50 years or greater |

| McCabe et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample, of whom 577 sexual minority adults | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year substance use disorder† | No associations on its own; Positive association in combination with lifetime gender and racial discrimination as well as with past year gender and racial discrimination |

| Span & Derby (2009) | 72 sexual minority adults in Los Angeles CA | Cross-sectional | Internalized | Past month drinking frequency | Negative association at low depressive symptoms; no association at high depressive symptoms |

Composite measure that combined alcohol with tobacco and/or illicit drug use

The majority of papers (n=13, 72%) reported a global test, of which 10 (77%) found no association. The remaining three papers reporting a positive association presented conflicting evidence. For example, two papers reported a positive association between sexual orientation discrimination and any drinking (Gilbert, Perreira, Eng, & Rhodes, 2014; Ortiz-Hernandez, Tello, & Valdes, 2009), but two additional papers found no such association (Rivers, 2004; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2008). Further, in three papers sexual orientation discrimination was associated with hazardous drinking (Hequembourg & Dearing, 2013; Lehavot & Simoni, 2011; Weber, 2008); however, four papers found no relationship with hazardous drinking (D’Augelli, Grossman, Hershberger, & O’Connell, 2001; Igartua, Gill, & Montoro, 2003; M.W. Ross et al., 2001; Wong, Kipke, Weiss, & McDavitt, 2010).

A minority of papers (n=8, 44%) reported findings from complex analytic models. Of those, two studies tested mediators, finding an indirect association through affiliation with deviant peers among adolescents (Huebner, Thoma, & Neilands, 2015) or through decreased individual psychosocial resources among adult women (Lehavot & Simoni, 2011). It should be noted, however, that these analyses combined alcohol use with illicit drug use, thereby decreasing precision about alcohol outcomes. A third mediation analysis established that discrimination partially explained the association between same-sex attraction or self-identity as a sexual minority and alcohol use (Ortiz-Hernandez et al., 2009). Five papers reported tests of moderation, suggesting complex, conditional relationships that depended on gender, age, or depressive symptoms. Indeed, the differential effect of discrimination by gender emerged as a minor theme, with two studies finding associations among women but not men (Amadio, 2006; Amadio & Chung, 2004), and one finding an association only when sexual orientation discrimination was combined with concurrent gender discrimination (McCabe, Bostwick, Hughes, West, & Boyd, 2010).

Methodologically, a notable difference was the social-ecological level of the risk exposure. Equivalent proportions (n=8, 44%) focused on internalized homophobia and interpersonal experiences of discrimination, and a minority (n=2, 11%) measured both aspects of discrimination. There was nearly universal use of established measures of discrimination (n=17, 94%). Some studies adapted existing measures of racial/ethnic discrimination for use with sexual minorities, such as the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine et al., 2006) or Experiences of Discrimination Scale (Krieger & Sidney, 1996). Others utilized measures that had been developed specifically to assess internalized discrimination, such as the Homosexual Attitudes Inventory (Nungesser, 1983), Lesbian Internalized Homophobia Scale (Szymanski & Chung, 2001), and the Reactions to Homosexuality Scale (M. W. Ross & Rosser, 1996). Except for one analysis that used longitudinal data, all results were based on cross-sectional data. Samples included similar numbers drawn from city/community (n=6, 33%), state/regional (n=5, 28%), and national (n=7, 39%) populations; however, few samples (n=4, 22%) were obtained via probability sampling methods. Three-quarters of analyses (n=13, 72%) had no theoretical or conceptual framework. Given the mix of strengths and weaknesses, 65% of the papers were categorized as moderately good quality and 29% as low quality.

Gender Discrimination

Six papers assessed the relationship between gender discrimination (i.e., sexism) and alcohol outcomes, making it the smallest body of literature on a single topic. One study was set in Canada, and the remainder were based in the US. the majority (n=5, 83%) were recent, having been published in 2007 or later. Of this small set of papers, two presented findings from global tests of association, two from complex analyses (e.g., mediation, moderation), and two from both global test and complex analyses. Table 4 summarizes findings on gender discrimination by type of test.

Table 4.

Gender discrimination and alcohol outcomes: a summary of findings by type of test, 1980–2015.

| Study | Sample | Design | Discrimination level | Alcohol-related outcome(s) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests of global associations | |||||

| McCabe et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year substance use disorder† | No association for past year or lifetime discrimination |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample, of whom 20,089 women | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) | Positive association |

| Richman et al. (1992) | 137 students at a college of medicine in a US state (not specified) | Longitudinal cohort | Interpersonal | Past month drinking quantity | Positive association |

| Rowe et al. (2015) | 292 transgender female adolescents and young adults in San Francisco Bay Area | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past six month alcohol use | Positive association |

| Test s of mediated associations | |||||

| Zucker and Landry (2007) | 192 female students at a private college in Washington DC | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past two week binge drinking | Positive association through psychological distress |

| Tests of conditional associations | |||||

| McCabe et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year substance use disorder† | Positive association in combination with lifetime sexual orientation discrimination |

| McLaughlin et al. (2010) | 34,653 adults in US national sample, of whom 20,089 women | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses wave two) | Interpersonal | Past year alcohol use disorder (DSM-IV abuse or dependence) | Positive association under one coping style (not accepting & not disclosing discrimination); no association under other coping styles |

| Otiniano Verissimo et al. (2013) | 401 young adult Latinos in New York NY | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Past year substance use† | Positive association among women; negative association among men |

Composite measure that combined alcohol with tobacco and/or illicit drug use

Papers examined a variety of alcohol outcomes, finding largely positive associations. The sole null finding was a paper that found no association between past-year or lifetime gender discrimination and past-year substance use disorders (McCabe et al., 2010); however, the same paper found a positive association when gender discrimination was combined with lifetime sexual orientation discrimination. Among other complex analyses, one paper tested identified an indirect pathway from gender discrimination to binge drinking through increased psychological distress (Zucker & Landry, 2007), and another paper found that the association depended on coping (McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Keyes, 2010).

Equivalent proportions of papers were categorized as low (n=2, 33%), moderately good (n=2, 33%), and high (n=2, 33%) quality. Except for one paper using longitudinal data, all results were based on cross-sectional data. Samples were drawn from city/community (n=3, 50%), state/regional (n=1, 17%), and national (n=2, 33%) populations, with the majority (n=4, 67%) obtained via non-probability sampling methods. Theory was largely absent from the set of papers; only two papers provided an explicit theoretical justification for the analysis, citing minority stress models, stress and coping models, and intersectionality theory. Another paper implied a basis in a stress and coping framework but did not provide any supporting citations. All papers focused on interpersonal gender discrimination, of which the majority (n=4, 67%) used an established measure of discrimination, such as the Experiences of Discrimination Scale (Krieger et al., 2005), Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997), or the Schedule of Sexist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1997).

Generalized discrimination

A final set of four papers reported findings for generalized discrimination, in which the cause of discrimination was either not distinguished or several possible types were collapsed. For example, one paper assessed experiences of workplace discrimination “because of gender, race or color” (p. 72), thus failing to differentiate its underlying cause (Yen, Ragland, Greiner, & Fisher, 1999b). The remaining three papers measured discrimination in multiple domains (e.g., race, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, among others) but collapsed all types into a single indicator for analysis (Capezza, Zlotnick, Kohn, Vicente, & Saldivia, 2012; Coelho, Bastos, & Celeste, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, Corbin, & Fromme, 2011). These approaches resulted in decreased detail about the exposure of interest. Thus, overarching conclusions are difficult, yet these papers may still contribute relevant information. Table 5 summarizes findings on generalized discrimination by type of test.

Table 5.

Generalized discrimination and alcohol outcomes: a summary of findings by type of test, 1980–2015.

| Study | Sample | Design | Discrimination level | Alcohol-related outcome(s) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tests of global associations | |||||

| Capezza et al. (2012) | 2839 adolescent & adult primary care patients in Concepcion & Talcahuano Chile | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | Positive association |

| Yen et al. (1999) | 993 adult transit workers in San Francisco CA | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking; drinking-related problems | No association with hazardous drinking; positive association with drinking-related problems |

| Tests of mediated associations | |||||

| Hatzenbuehler et al. (2011) | 1539 adolescent & young adult college students in Austin TX | Longitudinal cohort (analytic sample uses final two waves) | Interpersonal | Binge drinking; drinking-related problems | No association with binge drinking; positive association with drinking-related problems through drinking as a coping strategy |

| Tests of conditional associations | |||||

| Coelho et al. (2015) | 1,023 adolescent & young adults college students in Florianopolis Brazil | Cross-sectional | Interpersonal | Hazardous drinking | Positive association among mid-course students; no association among first-or last-year students |

There was one instance of inconsistent findings. One paper found a global positive association between generalized discrimination and hazardous drinking (Capezza et al., 2012) while another paper found no such association; however, the second paper identified a global positive association between generalized discrimination and drinking-related problems (Yen et al., 1999b). This was consistent with a third paper that found an indirect association with drinking-related problems through motivation to drink as a coping strategy (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2011). The final paper, testing a conditional model, found that a positive association with hazardous drinking only existed for mid-course university students; there was no association for either first-or last-year students.

These studies of generalized discrimination were categorized as moderately good (n=3, 75%) or high quality 9n=1, 25%). All analyses used probability samples drawn from local populations (i.e., single metropolitan areas), two in the US, one in Chile, and one in Brazil. In all cases, discrimination was measured at the interpersonal level, with two studies using established instruments. Only one study provided a theoretical justification for its analysis.

Other Types of Discrimination

Few studies investigated other types of discrimination in relation to alcohol use. For example, we found no studies that examined discrimination due to religion or disability status. One paper reported an analysis of discrimination due to age or physical appearance using a subset of US African Americans in the Panel Study on Income Dynamics—Transition to Adulthood Study (Madkour et al., 2015); however, results found no association between either type of discrimination and the study’s main outcome, heavy episodic drinking. Another paper looked at ageist attitudes and behaviors among college students at a single US university and their relationship to alcohol use (Popham, Kennison, & Bradley, 2011). Results showed a conditional relationship by gender, such that both aspects of ageism were correlated with drinking frequency and recent binge episodes in young men but not young women. As the study sought to understand how ageist attitudes held by young adults might shape their own alcohol use, it fails to explain how experiences of age discrimination could be associated with drinking among older adults.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the scientific literature specifically devoted to discrimination and alcohol-related outcomes. Although some previous reviews of discrimination have included substance use, their utility may be limited as they collapsed alcohol and illicit drug use. Given alcohol’s status as a legal, socially acceptable, and widely available psychoactive drug, examining it as a distinct set of outcomes is warranted.

The balance of findings reviewed here suggests a positive association. In other words, as experiences of discrimination increase, alcohol consumption, drinking-related problems, and risk of disorders tend also to increase. As we found much variation in the papers included in our review, with some population groups and types of discrimination receiving ample attention and others having been studied very little, the evidence base is quite inconsistent. Thus, despite generally supportive findings, important gaps remain. Further, the frequent findings of conditional relationships suggest that any claims about discrimination and alcohol outcomes must be qualified. We conclude that it is no longer appropriate to speak broadly of global associations; rather, scientists must specify the group, type and level of discrimination, and alcohol outcome when making claims about discrimination and drinking.

This review advances knowledge of the social determinants of alcohol misuse by addressing a key gap. Although the past three decades have seen steadily increasing interest in discrimination as a factor shaping health behaviors and outcomes, we have lacked a comprehensive understanding of its effect on alcohol use in the now voluminous literature. Indeed, several previous critical and systematic reviews have only modestly advanced our understanding because they failed to distinguish hazardous drinking from any drinking or combined alcohol with other substance use. This review provides a focused report of findings about alcohol use. Further, it may serve as a guide to inform future research. For example, we envision researchers using the detailed tables as evidence guides about specific outcomes and groups as they prepare future research projects.

We found that the largest proportion of papers was devoted to interpersonal experiences of racial discrimination among African Americans. This is not unexpected given that the majority of papers included in this review were based in the United States and that racism has had a prominent place in American social science research since the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Although the literature appears mature, especially considering the frequent use of complex mediated or moderated analyses, we note some aspects of it that are underdeveloped. For example, some racial/ethnic groups have received relatively little attention. It remains unknown whether findings based on African American samples are generalizable to Asian and Pacific Islander, Native American, or Latino groups given widely different histories and socio-political contexts. With an increasingly diverse society, attention must be directed towards other minority groups, either in group-specific studies or disaggregated analyses of large, diverse samples. Further, studies have relied almost exclusively on measures of interpersonal experiences. The contributions of internalized and systemic/structural racial/ethnic discrimination have yet to be unexplored.

In contrast to racial/ethnic discrimination, studies of sexual orientation discrimination, which constitute the second most frequently studied topic, present an example of a broader conceptualization of the risk exposure. Among papers reviewed, we found equivalent attention to internalized discrimination as well as interpersonal experiences. Moreover, a very high proportion of studies used established measures of discrimination, which improves the comparability of findings across studies. Despite these advantages, the sexual orientation discrimination literature suffers from important limitations. For example, the overwhelming majority of findings were based on cross-sectional data obtained from non-probability samples of limited scope. This substantially weakens our ability to make inferences, not only precluding assessments of causation but also constraining the generalizability of findings. Another striking feature is the degree of null findings. As several studies found that gender moderates the relationship of sexual orientation discrimination and alcohol outcomes, it raises the possibility of differential processes. Indeed, there may be an effect of sexual orientation discrimination for women but not men. Further research is needed to assess gender-specific associations.

In addition to summarizing findings, this review assessed the methods underlying the evidence. We sought not only to determine what is known, but also how it is known. In light of both aims, we make several recommendations to strengthen the evidence base. First, we advocate for the use of standardized measures of discrimination, which may decrease measurement error and increase comparability of findings. A number of multiple-item instruments are available. Some, such as the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997), may capture multiple types of discrimination through follow-up questions about attribution. Other instruments may have been created to measure one type of discrimination but could be adapted to another, as the Schedule of Sexist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1997) was derived from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996). Given ample extant resources, the continued use of non-standard and non-validated measures cannot be supported. Related to measurement, there is a growing literature that debates the utility of focusing on perceptions of discrimination, which requires recognition and attribution, versus experiences, which may or may not be labeled as discrimination (Bastos, Celeste, Faerstein, & Barros, 2010; Krieger, 2012). As measures based on different conceptualization can yield different results, researchers must be explicit about their conceptualization and consider how it may shape findings.

Further, we encourage investigation of all possible social-ecological levels of discrimination. As noted previously, the literature on sexual orientation discrimination provides an example of sustained research on internalized homophobia and heterosexism. While admirable, our overall understanding of the many levels of discrimination remains underdeveloped. In particular, we encourage studies of systemic/structural discrimination, which may elaborate how context shapes differences in population patterns of alcohol use, such as through degree of residential segregation or the absence of non-discrimination ordinances. In their exploration of structural racism and heart attack, Lukachko and colleagues (2014) provide a model of such an approach that may be applicable to alcohol outcomes.

Second, we call for more complex analyses, particularly of mediated and conditional associations, for all types of discrimination. This follows our earlier conclusion that it is no longer appropriate to speak broadly of global associations. Basic questions have been sufficiently addressed; to advance knowledge, we must now identify the processes through which discrimination affects alcohol outcomes and the conditions under which risk may be exacerbated or attenuated. Doing so may identify leverage points for harm-reduction interventions. The literature on racial/ethnic discrimination serves as a model, as it has evolved, albeit unevenly, from descriptive studies to analytic research. A number of intrapersonal factors have been identified, such as psychological distress and minority group identification; however, many more remain to be tested. Here, we caution against following brute empiricism. Behavioral theories should guide our selection of potential mediating and moderating variables. In return, empirical findings may help refine theoretical models.

Finally, we strongly urge researchers to eschew non-probability sampling. Some literature, such as that on sexual orientation discrimination, has been overly reliant on convenience samples, which greatly impacted our quality assessments. The recent development of sophisticated methodologies, such as respondent-driven sampling (Ramirez-Valles, Heckathorn, Vazquez, Diaz, & Campbell, 2005) and time-space sampling (MacKellar, Valleroy, Karon, Lemp, & Janssen, 1996), can be used to obtain approximately representative samples when no sampling frame is possible. This is particularly important for discrimination research as the stigmatized characteristics that create these hidden and hard-to-reach populations may also be the basis of discrimination.

Several potential limitations of this review must be considered. Most importantly, we restricted the sample to English language papers, which may have constrained our conclusions by excluding potentially relevant findings published in other languages. In particular, we note the well-developed field of Latin American social medicine, which has received scant attention in the English-speaking world (Tajer, 2003; Waitzkin, Iriart, Estrada, & Lamadrid, 2001). With its emphasis on social and political determinants of health, Latin American social medicine has the potential to contribute relevant findings about discrimination. As an exemplar of this approach, we highlight the work of Vázquez Pedrouzo (2004), who used a framework of multiple social and structural determinants to identify factors contributing to alcohol-related traffic accidents in Uruguay. We look forward to a future review of the Spanish and Portuguese language literature (e.g., SciELO and LILACS data bases), which may extend the current set of findings. Similarly, we recognize that the overwhelming majority of papers were based on research in the United States, which may limit the relevance of our findings in other areas. For example, findings about racial discrimination among African Americans may not hold for other minority groups or nations. As discrimination is a social phenomenon embedded within specific cultural and historical contexts, we look forward to research with non-US populations that will provide a fuller understanding of the effects of discrimination and may identify generalizable factors. Finally, we were unable to include a meta-analysis in this review due to the heterogeneity of study designs, measures, outcomes, and populations. While a pooled estimate of the effect of discrimination on alcohol use would represent an epidemiological advance, its absence from this review does not impede public health. The preponderance of findings provide sufficient evidence of the injurious effect of discrimination to motivate risk-reduction initiatives.

In summary, this review finds support for the widely accepted proposition that discrimination is associated with heavy and hazardous drinking, but cautions that claims about the relationship must be specific rather than general. It highlights the uneven evidence base and suggest directions for future research. Attention to this relationship has the potential for broad population benefits, as both discrimination and alcohol misuse are associated with directly and indirectly harmful effects.

Summarizes reports on the relationship between discrimination and alcohol outcomes

Assesses methods underlying research on discrimination and alcohol use

Majority of findings are based on studies of racism among African Americans

Some population groups and types of discrimination have received scant attention

Makes recommendations to improve future research

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Helena M. VonVille, Barbara Folb, and Joey Nicholson for their assistance in conceptualizing this review, Michael Sholinbeck for his assistance with the literature search, and Angela Harbour for her assistance revising the paper. This manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (T32007240; P50AA005595). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsor had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of findings, or writing of this paper and the decision to submit it for publication.

Appendix A. Search terms by data base

| Data base | Exposure terms | Outcome terms |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | MeSH term: prejudice MeSH term: social discrimination “Unfair treatment” “Transphobia” |

MeSH term: alcohol-related disorders MeSH term: alcohol drinking “Heavy episodic drinking” “Risky drinking” |

| Embase | Emtree term: social discrimination Emtree term: social psychology Emtree term: prejudice “homophobia “transphobia “unfair treatment |

Alcohol consumption Alcohol abuse Alcoholism |

| PsycInfo | Subject term: social discrimination Subject term: prejudice Subject term: racism Subject term: sexism Subject term: homosexuality (attitudes toward) Subject term: ageism “transphobia” “unfair treatment” |

Subject term: alcohol drinking patterns Subject term: alcohol abuse Subject term: alcoholism |

| Sociological Abstracts |

Subject term: discrimination Subject term: prejudice Subject term: racism Subject term: sexism Subject term: heterosexism Subject term: classism “transphobia” “unfair treatment” |

Subject term: alcoholic beverages Subject term: alcohol abuse Subject term: alcoholism |

| Rutgers Alcohol Studies Database |

“discrimination” “prejudice” “racism” “sexism” “ageism” “homophobia” “transphobia” |

N/A (data base focused exclusively on alcohol) |

| NIAAA ETOH Archival Database |

“discrimination” “prejudice” “racism” “sexism” “ageism” “homophobia” “transphobia” |

N/A (data base focused exclusively on alcohol) |

NIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acosta SL, Hospital MM, Graziano JN, Morris S, Wagner EF. Pathways to drinking among Hispanic/Latino adolescents: perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, and peer affiliations. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2015;14(3):270–286. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2014.993787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadio DM. Internalized heterosexism, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Addict Behav. 2006;31(7):1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadio DM, Chung YB. Internalized homophobia and substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2004;17(1):83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Armstead CA, Lawler KA, Gorden G, Cross J, Gibbons J. Relationship of racial stressors to blood pressure responses and anger expression in black college students. Health Psychol. 1989;8(5):541–556. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.8.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EL, Irwin JA. Age differences in the correlates of problematic alcohol use among southern lesbians. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(2):295–298. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E, Barros AJ. Racial discrimination and health: a systematic review of scales with a focus on their psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IM, Culhane JF, Webb DA, Coyne JC, Hogan V, Mathew L, Elo IT. Perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, smoking, and recent alcohol use in pregnancy. Birth. 2010;37(2):90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, Denny N. The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically White institution. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18(1):45–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shea S, Jackson SA, Shrager S, Blumenthal RS. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, smoking and alcohol consumption in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs DR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(9):1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton MH, O’Hara RE, Covault J, Scott D, Tennen H. A mediational model of racial discrimination and alcohol-related problems among african american college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(2):228–234. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodish AB, Cogburn CD, Fuller-Rowell TE, Peck S, Malanchuk O, Eccles JS. Perceived Racial Discrimination as a Predictor of Health Behaviors: the Moderating Role of Gender. Race Soc Probl. 2011;3(3):160–169. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9050-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Chen YF. Perceived discrimination and longitudinal increases in adolescent substance use: gender differences and mediational pathways. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen YF, Kogan SM, Smith K. The Adults in the Making program: long-term protective stabilizing effects on alcohol use and substance use problems for rural African American emerging adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):17–28. doi: 10.1037/a0026592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Perceived discrimination and alcohol use among Black and White college students. J Acohol Drug Educ. 2007;51(1):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Rieppi R, Kelly KP, Gerin W. Perceived racism and blood pressure: a review of the literature and conceptual and methodological critique. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(1):55–65. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Langille D, Tanner J, Asbridge M. Health-compromising behaviors among a multi-ethnic sample of Canadian high school students: risk-enhancing effects of discrimination and acculturation. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2014;13(2):158–178. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.852075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchianeri MM, Eisenberg ME, Wall MM, Piran N, Neumark-Sztainer D. Multiple types of harassment: associations with emotional well-being and unhealthy behaviors in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):724–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Antonakos CL, Tsuchiya K, Assari S, De Loney EH. Masculinity as a moderator of discrimination and parenting on depressive symptoms and drinking behaviors among nonresident African-American fathers. Psychol Men Masc. 2013;14(1):47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, de Dios MA, Castro Y, Vaughan EL, Castillo LG, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Molleda LM. Alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms among late adolescent Hispanics: Testing associations of acculturation and enculturation in a bicultural transaction model. Addict Behav. 2015;49:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. J Adolesc. 2015;42:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capezza NM, Zlotnick C, Kohn R, Vicente B, Saldivia S. Perceived discrimination is a potential contributing factor to substance use and mental health problems among primary care patients in Chile. J Addict Med. 2012;6(4):297–303. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182664d80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Takeuchi DT, Barbeau EM, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Stoddard AM, Krieger N. Alcohol disorders among Asian Americans: associations with unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identification (the National Latino and Asian Americans Study, 2002–2003) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(11):973–979. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.066811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LJ, Ornelas IJ, Lyles CR, Williams EC. Racial/ethnic workplace discrimination: association with tobacco and alcohol use. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle JE, Whitbeck LB. Alcohol use trajectories and problem drinking over the course of adolescence: a study of North American indigenous youth and their caretakers. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):228–245. doi: 10.1177/0022146510393973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Szalacha LA, Menon U. Perceived discrimination and its associations with mental health and substance use among Asian American and Pacific Islander undergraduate and graduate students. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(6):390–398. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.917648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54(10):805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TT, Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Whitfield KE. Everyday discrimination and mood and substance use disorders: a latent profile analysis with African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Addict Behav. 2015;40:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho IZ, Bastos JL, Celeste RK. Moderators of the association between discrimination and alcohol consumption: Findings from a representative sample of Brazilian university students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2015;37(2):72–81. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2014-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]