Abstract

Tremendous strides have been made in the treatment of various oncological diseases such that patients are surviving longer and are having better quality of life. However, the success has been tainted by the iatrogenic cardiac toxicities. This is especially concerning in the younger population who are facing cardiac disease such as heart failure in their 30s and 40s as the consequence of the anthracycline’s side-effect (used for childhood leukemia and lymphoma). This resulted in the awareness of cardio-toxic effect of anticancer drugs and emergence of a new discipline: Onco-cardiology. Since then numerous anticancer drugs have been correlated to cardiomyopathy. Additionally, other cardiovascular effects have been identified which includes but no limited to the myocardial infarction, thrombosis, hypertension, arrhythmias and pulmonary hypertension. This review examines some of the anticancer agents mitigating cardiotoxicity and presents current knowledge of molecular mechanism(s). The aim of the review is to ignite awareness of emerging cardio-toxic effects as new generation of anticancer agents are being tested in clinical trials and introduced as part of therapeutic armamentarium to our oncological patients.

Introduction

The National Cancer Institute defines cardiotoxicity as “toxicity that affects the heart” (www.cancer.gov/dictionary/). It’s quite a simplistic explanation which essentially describes the word “cardiotoxicity” rather than defines it. One of the more accurate clinical descriptions of cardiotoxicity has been formulated by the cardiac review and evaluation committee supervising trastuzumab clinical trials, who defined drug-associated cardiotoxicity as one or more of the following: 1) Cardiomyopathy characterized by a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) globally or due to regional changes in interventricular septum contraction; 2) symptoms associated with congestive heart failure (CHF); 3) signs associated with HF, such as S3 gallop, tachycardia, or both; 4) decline in initial LVEF of at least 5% to less than 55% with signs and symptoms of heart failure or asymptomatic decrease in LVEF of at least 10% to less than 55%1. This definition has a limited scope as it does not include subclinical cardiovascular damage that may occur early in response to some of the chemotherapeutic agents. Other cardiac factors such as coronary artery disease and rhythm disturbances or other affected cardiovascular organ system such as pulmonary hypertension has been excluded also. Thus, this definition while ideal for cardiomyopathy, does not encompasses the broad scope of unwanted cardiovascular effects of the anticancer drugs. Although recent upsurge in the interest of cardio-toxicity mediated by the anticancer drugs has been due to an increased incidence of cardiomyopathy and consequent HF in oncological patients2, newer anticancer drugs have different array of cardiovascular effects. Therefore, collaborative efforts between the oncologists and the cardiologists are clearly warranted to screen, identify and manage our cancer patients for cardiac disease so that early intervention can provide boon to this cohort of highly specialized population.

This review paper will discuss chemotherapeutic mediated cardiomyopathy and beyond. It is not an exhaustive review of all the anticancer medication/regimen but it’s an attempt to provide examples of cardiovascular toxic effects of some of the prominent anticancer drugs. The paper outlines a clinical perspective and molecular mechanism involved with each anticancer drug. The research effort to attenuate, if not to ameliorate, cardio-toxic effects lies in the deeper understanding of the mechanism(s) behind anticancer mediated cardiotoxicity.

Cardiomyopathy

Anthracyclines

Clinical Perspective

In a retrospective analysis of over 4000 patients treated with doxorubicin (DOX), Von Hoff and colleagues3 found that 2.2% of the patients developed clinical signs and symptoms of CHF. Since the study identified CHF based on clinical assessment, incorporation of subclinical left ventricular dysfunction would result in higher incidence of the cardiovascular disease in DOX patients; as acknowledged by the authors themselves3. This study went on to conclude that the prevalence of heart failure markedly increased with a cumulative dose of 550 mg/m2 of DOX3, which is now recognized as one of the greatest determinants in the development of anthracycline mediated heart failure4.

Subsequently, the cardiotoxicity in DOX treated patients was prospectively assessed in three clinical trials (two in breast and one in non-small cell lung cancer) conducted between 1988 and 1992. The studies showed that the rate of conventional DOX-related CHF was 5% at a cumulative dose of 400 mg/m2, 16% at a dose of 500 mg/m2 and 26% at a dose of 550 mg/m24. While there is a clear dose-response associated with cardiotoxicity, histopathologic changes can be seen in endomyocardial biopsy specimens from patients who have received as little as 240 mg/m2 of DOX5. Moreover, subclinical events occurred in about 30% of the patients, even at doses of 180–240 mg/m26, although they were observed 13 years after the treatment was received. Even doses as low as 100 mg/m2 have been associated with reduced cardiac function5, 7. These findings suggest that there is no safe dose of anthracyclines. Conversely, early studies suggested that some patients had no significant cardiac complications despite achievement of the doses as high as 1000mg/m223. Therefore, individual susceptibility to cardiomyopathy may vary. However, the current consensus is that DOX causes cardiomyopathy.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

Anthracycline mediated cardiomyopathy has been studied extensively. Among the pathways implicated in anthracycline mediated toxicity involves production of reactive oxygen species, formation of iron complexes resulting in intracellular damage. However, we identified a direct target of doxorubicin that provides a unifying mechanism encompassing most of the implicated pathways.

It has been well-studied that one of the mechanisms of DOX induced tumor-cytotoxic effect is mediated by topoisomerase II alpha inhibition8. Toposiomerase II alpha is an enzyme that regulates the overwinding or underwinding of DNA during its repair process9. They play an important role in regulating cellular processes such as replication, transcription, and chromosomal segregation by altering DNA topology9. On the other hand, topoisomerase II beta (Top II B) serves the same function in quiescent cells. Since they share catalytic mechanisms and have a high degree of amino acid similarity (~70% identity at the amino acid level)10; we embarked on a project to study the role of Top II B in murine cardiac cells treated with DOX. We successfully demonstrated that11: (a) in rats, the molecular phenotype of acute and chronic DOX cardiomyopathy is characterized by the formation of a ternary DNA–Top II B–DOX cleavage complex, that triggers double-strand breaks in the DNA; (b) the acute stage is characterized by upregulation of the apoptotic pathway signaling, specifically Apaf-1, Bax, Mdm-2 and Fas. Under chronic condition, (c) the genes implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative phosphorylation were activated by downregulation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha (Ppargc-1a) and beta (Ppargc-1b)11. This downregulation resulted in (d) decrease in the key components of the electron transport chain such as Ndufa3, Sdha, and Atp5a1 thus culminating into (e) ultrastructural mitochondrial damage with vacuolization11. The mitochondria were also (f) dysfunctional as measured by oxygen consumption and changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. The end result was (g) an increase in end systolic and end-diastolic volumes with decrease in ejection fraction11. The formation of the ternary complex is also responsible for the production of most (70%) DOX-induced ROS. Therefore the oxidative stress is preferentially a result of the DOX-induced DNA damage and of the consequent changes in the transcriptome rather than of the redox-cycling of DOX. Transgenic mice with cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of Top II B were indeed protected from the acute and progressive or chronic DOX-induced heart failure, and did not exhibit the severe cardiomyopathic phenotype of the wild type mice. Therefore, Top II B is required to initiate the entire phenotypic cascade of DOX-induced cardiomyopathy11. Other studies also identified the activation of the p53 pathway to DNA-damage and the consequent apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cultured cardiomyocytes treated with DOX12, 13.

The corroborating evidence of Top II B mechanism is provided by the use of dexrazoxane (DEX). In vivo, DEX has shown significant cardio-protection against DOX in various preclinical models such as mouse, rat, hamster, rabbit, and dog14–17. In addition, the cardioprotective effects were evident in both acute and chronic models of DOX-induced cardiomyopathy18, 19. These findings were extended to human subjects in various clinical trials also16, 20–23. It appears that DEX can block ATP hydrolysis and inhibit the reopening of the ATPase domain, thereby trapping the topoisomerase complex on DNA and blocking enzyme turnover24 which may be its predominant mechanism. Therefore, DEX inhibits DOX’s activity on TOP II B catalytic site, thereby providing cardio-protection. In essence, DOX/DNA/Top II B ternary complex may be the prime mediator of anthracycline mediated cardiomyopathy.

Trastuzumab

Clinical Perspective

The first evidence that trastuzumab might be involved in cardiomyopathy was identified in a pivotal Phase III clinical trial designed to assess its efficacy in the breast cancer patients. The outcome was an improved survival in this cohort25. However, heart failure was detected in 27% of patients treated with the regimen of anthracycline, cyclophosphoamide, and trastuzumab25. Subsequently, several large clinical trials confirmed the importance of trastuzumab in increasing disease-free survival from cancer, but also established traztuzumab’s association with heart failure26, 27. The incidence of cardiomyopathy dropped to 13% when anthracyclines were not administered concurrently with trastuzumab; although these patients were previously treated with anthracycline. In the adjuvant trials, 1.7–4.1% of trastuzumab-treated patients developed CHF27 when anthracycline was not part of the therapeutic regimen. Thus, trastuzumab came with a black box warning of possible inducing cardiomyopathy.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

Early studies indicated that Erb-B2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase 2 (ERBB2), and its activating ligand, neuregulin-1 (Nrg1), play an integral role in the cardiac development. Germline deletion of ERBB228 or Nrg129 in the mice results in mid-gestational lethality owing to dysmorphic ventricular development. This suggests that ERBB2 signaling is required for cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac development. Mice with the cardiac-specific deletion of ERBB2, after cardiac development, were viable30. However, these mice developed dilated cardiomyopathy as they aged and had decreased survival when subjected to pressure overload induced by aortic banding31, 32. Cardiomyocytes from these mice also exhibited enhanced sensitivity to the anthracyclines, thus alluding to a mechanistic synergy between anthracycline and trastuzumab in clinical population31.

ERBB2 activation by its ligand in cardiomyocytes activates the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways that promotes cardiomyocyte survival during adulthood33. Expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL in the hearts of ERBB2 cardiac specific deleted newborn mice partially prevented the heart chamber dilation and the impaired contractility seen in adulthood31. Thus inhibition of ERBB2 signaling is important in normal cardiomyocyte function. However, unlike trastuzumab, lapatinib, the small molecule dual inhibitor of ERBB2 and EGFR, shows limited depression of cardiac function34, 35, and therefore questioning the underlying mechanism of ERBB2 in mitigating traztuzumab mediated cardiac dysfunction. Similarly, pertuzumab, another inhibitor of ERBB2 signaling also showed marginal development of cardiomyopathy36. Although it is possible that other actions of lapatinib such as activation of AMPK37 and pertuzumab inhibition of ligand-mediated formation of heterodimer38 might confer cardio-protective effect. Therefore, the precise mechanism involved in trastuzumab mediated cardio-toxicity remains elusive.

Myocardial Ischemia

5-Fluorouracil

Clinical Perspective

The incidence of myocardial ischemia ranged from 1.2–1.6% in patients treated with 5-FU, although reports of up to 68% also exists39–41. The proportion increases with escalating doses (~ 10% with 800 mg/m2)39. Other trials have higher incidence of ischemia with mortality rate of 2.2 – 13% attributed to 5-FU39}41, 42. The mean onset time for the ischemia is generally 72 hours although earlier episodes have also been reported43. The incidence is especially high in patients with previous coronary artery disease (~5–10 fold increase)44, 45 and their recurrence rate is high in patients with previous ischemic episodes secondary to 5-FU administration43. Furthermore, mode of administration, specifically continuous infusion of 5-FU have been associated with higher rates of cardiotoxicity (7.6%) as compared with bolus injections (2%)39, 40, 46.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

Coronary artery thrombosis, arteritis, or vasospasm have been proposed as some of the potential underlying mechanisms47. Vasospasm seems to be the working hypothesis, however, the failure of ergonovine and 5-FU to elicit vasospasm during cardiac catheterizations, weakens the potential role of 5-FU–induced vasospasm47–50. In one of the studies, elevated endothelin levels were found with 5-FU administration47, 51. However, the lack of evidence if endothelin was cause or an effect of 5-FU, questions the validity of this pathway. Therefore, alternative mechanisms have been speculated, including direct toxicity of the myocardium, inducing hypercoaguable state, and autoimmune response47, 50. Additionally, metabolic pathways are also implicated. Fluoroacetate is generated from a degradation product of parenteral 5-FU preparations, fluoroacetaldehyde. This accumulation of fluoroacetate interferes with the Krebs cycle39, 50. This may in turn result in citrate accumulation which might be a causative mechanism39, 47, 50 as 5-FU has been known to induce dose- and time-dependent depletion of high-energy phosphates in the ventricle39, 49. Other mechanism such as protein kinase C mediated vascular smooth muscle activation and subsequent vasoconstriction by Mosseri et al52 further add to the complexity of 5-FU mediated cardiotoxicity52. Lastly, 5-FU mediated cardio-toxicity may also involve apoptosis of myocardial and endothelial cells resulting in inflammatory lesions mimicking toxic myocarditis50, 53. Therefore, the exact mechanism remains undetermined. A complete analysis of 5-FU putative pathways involved in cardiovascular dysfunction can be found elsewhere54.

Hypertension

Bevacizumab

Clinical Perspective

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the VEGF-A ligand that binds to its circulating target and downregulates angiogenesis55. It has been approved by the European Medicines Agency and by the United States Food and Drug Administration, and it is the first- or second-line chemotherapy for the treatment of many advanced solid tumors, including colorectal cancer (CRC), non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, glioblastoma, renal cell cancer (RCC), ovarian cancer, and cervical cancer56–63. Although the efficacy of bevacizumab has been demonstrated in many clinical trials, its use has been associated with many cardiovascular events, including high risk hypertension (HTN). Overall incidence of 4%–35% reported in clinical trials58, 62, 64. This variability might be attributed to the different selection criteria used in clinical trials (eg, the age of the patients included), as well as to differences in the definition of HTN.

In Phase I trials, bevacizumab was safely administered at a dose up to 10 mg/kg without dose-limiting toxicities, but mild increases in BP were observed at higher dose levels tested65. Interestingly, patients with RCC and breast cancer who received the drug at a dose of 5 mg/kg weekly had a higher risk of developing HTN66. The median interval from initiation of bevacizumab to the development of HTN is approximately 4.6–6 months. Bevacizumab-related HTN can develop at any time during treatment, and the data suggest that there is a dose relationship67. Specifically, the risk of HTN is increased by three times with low doses and 7.5 times with high doses of bevacizumab68. A majority of the patients who developed HTN in clinical trials were treated with antihypertensive medication and continued bevacizumab. This is particularly important, since there is a clear association between the efficacy of and duration of exposure to bevacizumab69. However, HTN resistant to medication might lead to discontinuation of bevacizumab in 1.7% of patients70. Single cases of hypertensive crisis with encephalopathy and subarachnoid hemorrhage have also been reported70.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

There are supportive evidence for two potential mechanisms by which VEGF signaling pathway (VSP) inhibition may lead to hypertension: 1) acute decreased production of vasodilating factors leading to arteriolar vasoconstriction, and 2) chronic depletion of microvascular endothelial cells leading to a net reduction in normal tissue microvascular density, a process called rarefaction. The evidence for diminished vasodilator production is indirect. The endothelial nitric oxide synthase enzyme is post-translationally activated by the VSP71. Studies of bevacizumab, incubated with human umbilical vein endothelial cells, demonstrate reduction in nitric oxide production within hours of incubation72. The evidence for the second potential mechanism comes from a small clinical trial of 20 patients. In this cohort, bevacizumab induced hypertension was accompanied by endothelial dysfunction and capillary rarefaction; both changes are closely associated with the rise in the blood pressure that was observed in most patients73. Bevacizumab targeted not only the pathological and ‘switched’ vessels feeding the tumor area, but also the ‘normal’ arterioles and capillaries far from the tumor zone in these study patients73. Other systems such as endothelin74 and endothelial dysfunction75 increase has also been implicated in TKIs mediated hypertension.

Multi-targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Bevacizumab was one of the first approved members of VSP inhibitors as an anticancer agent56. The approval of bevacizumab has been followed by FDA approval of five additional VSP inhibitors for various cancer types. Sunitinib (Sutent), sorafenib (Nexavar), pazopanib (Votrient), axitinib (Inlyta), and vandetanib (Caprelsa) are all small molecule multiple tyrosine kinase inhibitors with varying degree of specificities for VEGF receptors. Studies have shown that there seems to be class effect when it comes to hypertension and, like the therapeutic efficacy, VSP inhibitors also display different degrees of hypertension. This has been extensively discussed elsewhere75–77

Arrhythmias

Bradyarrhythmia

Thalidomide

Clinical Perspective

Thalidomide (a-N-phthalimidoglutarimide) was initially manufactured in West Germany and was marketed as an antiemetic and sedative. It was also used as anxiolytics and for insomnia. Later on when the marketing of over-the-counter thalidomide began for morning sickness, an increase in limb malformation was noted. Therefore, given its serious side-effect of phocomelia (limb malformation), it was discontinued. Over the years it has been found that thalidomide act as a potent immunosuppressive and antiangiogenic agent78, 79 by inhibiting the phagocytic ability of inflammatory cells and the production of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor- alpha (TNF-α). Therefore, thalidomide emerged as an anticancer agent. Initial trials with thalidomide showed that patients with advanced and refractory multiple myeloma, in whom salvage therapy failed after single and even tandem auto-transplants, one-third of this cohort responded markedly to thalidomide80, 81. Eventually, thalidomide became a member of anti-neoplastic armamentarium in the fight against multiple myeloma.

An observation of bradycardia in thalidomide group prompted Fahdi et al82 to do a prospective chart review on 200 consecutive patients enrolled in an ongoing phase III clinical trial for patients with multiple myeloma. In this study, patients were randomized to receive either thalidomide or placebo in addition to the standard therapy. It was found that 53% of patients had bradycardia in thalidomide group defined as resting heart rate of < 60 beats per minute. Roughly 15% had heart rate below 30 and five patients (roughly 10% of the bradycardic group) required permanent pacemaker. The bradycardia was neither due to concomitant administration of beta-blocker not any electrolyte imbalance. The baseline characteristics in both thalidomide and placebo group were well-matched82.

Thalidomide induced bradycardia has been also found in non-oncological patients. A pilot study was carried out to determine the efficacy of thalidomide in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis83. Thalidomide was initiated at 100 mg per day for 6 weeks. Thereafter, the dose was increased every week by 50 mg until a target dose of 400 mg per day was achieved with goal of continuing the maximum dose for next 12 weeks. During the last 12 weeks of thalidomide treatment, nine thalidomide patients (50%) developed bradycardia defined as a heart rate below 60 beats per minute (bpm) and ranged from 46 to 59 bpm. Mean heart rate dropped by 17 bpm in the thalidomide treatment. Severe symptomatic bradycardia of 30 bpm occurred in one patient. Furthermore, a patient died from sudden unexpected death. The study was terminated prematurely for safety concerns83. Therefore, thalidomide appears to induce bradycardia in some patients.

Potential Molecular Mechanism

A balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system balance exists which maintains a narrow physiologic stable heart rate. Studies have shown that dorsal motor neurons, which are a part of the nucleus of vagus nerve (paprasympathetic system), are completely inhibited by TNF-α84. Since, thalidomide inhibits TNF-expression and activity, it could lead to overactivity of the parasympathetic system thus inducing bradycardia82. Bradycardic response was decreased by reducing the dose or discontinuing thalidomide, suggesting a reversible effect on sinus node function. Therefore, it is believed that thalidomide-related bradycardia may be due to its action on parasympathetic system and seems to be reversible in nature82.

QT Prolongation

Arsenic Trioxide

Clinical Perspective

QT prolongation with arsenic trioxide has been well-reported. The initial studies were looking at use of arsenic trioxide in promyelocytic leukemia. Although significant benefit was achieved in the studied cohort, 63% of the patients displayed QT duration above 500 ms. Compared with baseline, the heart rate-corrected (QTc) interval was prolonged by 30–60 msec in 36.6% of the patients85, 86. Retrospective analysis of Phase I and Phase II trials showed that, in treatment of advanced malignancies, arsenic trioxide resulted in increase in QT interval in 22% of the patients87. Furthermore, Schiller et al88 studied 70 patients who received arsenic for myelodysplastic syndrome and found that 24% patients developed QT prolongation. Although, there were clinically significant arrhythmias secondary to QT prolongation (which included atrioventricular block89, torsade de pointes90, ventricular tachycardia86 and sudden cardiac death91); other studies with QT prolongation were clinically uneventful88.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

The mechanism proposed ranges from neuropathy to electrolyte changes with arsenic interacting with magnesium90. Studies in guinea pigs have shown that prolonged action potential by arsenic trioxide is due to increase in calcium current as well as decreasing membranous expression of hERG channels92. However, other studies also suggest a direct inhibition of hERG channels also93. It appears that interplay between elevated calcium and reduced hERG channel expression/activity determines the QT interval in arsenic trioxide treated patient population93.

Multi-targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Clinical Perspective

Multi-targeted tyrosine kinase (TKI) inhibitors disrupt various mitogenic pathways in both cancer cells and the associated vasculature. Among the new medications of this class, sunitinib and its active metabolite SU012662 seemed to prolong QT interval in preclinical trials94. This finding was also translated to clinical population as the patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, treated with sunitinib resulted in QTc prolongation in 9.5% of the patients95. Recently, a retrospective analysis was carried out on the multi-targeted tyrosine kinases. In this multicenter clinical trial four centers in the Netherlands and Italy screened patients who were treated with erlotinib, gefitinib, imatinib, lapatinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, sunitinib, or vemurafenib96. A total of 363 patients were eligible for the analyses. At baseline measurement, QTc intervals were significantly longer in females than in males (QTcfemales=404 ms vs QTcmales=399 ms, P=0.027) as expected. A statistically significant increase was observed in the individual treated with sunitinib, vemurafenib, sorafenib, imatinib, and erlotinib (median 0394;QTc ranging from +7 to +24 ms, P<0.004)96. Especially, patients treated with vemurafenib were at increased risk of developing a QTc of greater than or equal to 470 ms, a threshold associated with an increased risk for arrhythmias96.

Similarly, another meta-analysis was carried out on trials looking at various TKIs (sunitinib, sorafenib, pazopanib, axitinib, vandetanib, cabozantinib, ponatinib and regorafenib)97. A total of 6548 patients from 18 trials were selected. QTc prolongation for the TKI vs no TKI arms was 8.66 (95% CI 4.92–15.2, P<0.001) versus 2.69 (95% CI 1.33–5.44, P=0.006), respectively, with most of the events being asymptomatic QTc prolongation. Furthermore, 4.4% and 0.83% of patients exposed to VEGFR TKI had all-grade and high-grade QTc prolongation, respectively97. During subgroup analysis, only sunitinib and vandetanib were associated with a statistically significant increase of QTc prolongation, with higher doses of vandetanib conferring greater risk. The rate of serious arrhythmias including torsades de pointes did not seem to be higher with high-grade QTc prolongation97. The risk of QTc prolongation was independent to the duration of the therapy97.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

TKIs mediated QTc interval prolongation is thought to be directly caused by a drug’s three-dimensional molecular structure interacting with myocardial hERG Kþ channels resulting in delayed impulse conduction98. Furthermore, another putative proposed mechanism of QTc prolongation that is not tested in preclinical studies is the inhibition of hERG Kþ channel protein trafficking. Interference with the translocation of hERG channel via chaperone proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane reduced hERG Kþ current99, thereby affecting cardiac repolarization. Therefore, hERG channels represents a putative molecular mechanism in TKI induced QTc prolongation.

Thrombosis

Venous Thromboembolism

Thalidomide

Clinical Perspective

Patients who received thalidomide as a monotherapy for the treatment of myeloma had a less than 5% risk of developing VTE81. However, when thalidomide is a part of a combination chemotherapeutic regimen, the risk is dramatically increased. Thrombosis rates were estimated at 10–20% for myeloma patients receiving thalidomide with dexamethasone100 and 20–40% for those taking it with doxorubicin101, 102. Rates as high as 43% of VTE were noted in a phase II clinical trial of thalidomide with gemcitabine and continuous infusion of fluorouracil in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma103. Prophylactic LMWH, but not low-dose warfarin, has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of thalidomide-associated VTE104.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

The mechanism by which thalidomide stimulates thrombosis is not fully elucidated. In a cross-sectional study of myeloma patients treated with or without thalidomide chemotherapy, levels of protein C, protein S and AT III, as well as lupus anticoagulant, factor V Leiden, factor II mutation or factor XI did not differ between the two groups105. One school of thought exists that the synergistic prothrombotic effect may exists between various chemotherapeutic agents and thalidomide resulting in the endothelial cell dysfunction and damage, thereby providing nidus for hypercoagulability106. Currently it’s a good theory but currently lacks empirical data.

Cisplatin

Clinical Perspective

Cisplatin interferes with DNA repair mechanism and therefore being used in numerous malignancies. In a retrospective analysis of the patients suffering from germline cell mutation and consequent cancer, treatment with cisplatin and bleomycin-based chemotherapy increaesd the risk of thrombosis by 8.4%107. Specifically, incidence was higher in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine at 17.6%108. Patients treated with radiation and low-dose cisplatin had a VTE incidence of 16.7% in invasive cervical cancer cohort. Additionally, patients with ovarian cancer treated with cisplatin, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide had an incidence of 10.6%109. Furthermore, cisplatin has also been implicated in stroke, recurrent peripheral arterial thrombosis and aortic thrombosis110. Recent meta-analysis of 8,216 patients from 38 randomized trials revealed that cisplatin increased the likelihood of a thromboembolic event by 1.67-fold111.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

The mechanisms by which cisplatin promote thrombosis are not well studied. In vitro evidence suggests that pharmacological doses of cisplatin increase tissue factor (TF) activity without any change in TF expression in human monocytes112. Alternatively, cisplatin has also been shown to induce platelet activation113, increase von Willebrand factor (vWF) levels114, 115, and induce endothelial cell apoptosis; latter pathway resulting in release of procoagulant endothelial microparticles that are able to generate thrombin through tissue factor independent pathways. Therefore, a succinct mechanism for cisplatin mediated VTE remains undetermined.

Arterial Thromboembolism

Bevacizumab

Clinical Perspective

Bevacizumab has been associated with an increased risk of arterial thromboembolism as defined by myocardial and cerebrovascular events. In a pooled analysis of 1,745 patients from five different randomized controlled trials in metastatic colorectal, non-small cell lung cancer, and metastatic breast cancer patients, the overall incidence of arterial thromboembolisms (ATEs) was 3.8%116. Specifically, the incidence of MI was 1.5% versus 1% in the bevacizumab and the control group, respectively116. In an observational study of 1,953 patients receiving bevacizumab with standard chemotherapy, the incidence of serious ATEs was 1.8% with 0.6% of the total population experiencing MI117. A more recent meta-analysis, which included 12,617 patients from 20 Phase II and III randomized controlled trials, also showed similar incidence of ATEs118. Bevacizumab was associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiac ischemia (RR =2.14; 95% CI: 1.12–4.08), but not stroke (RR =1.37; 95% CI: 0.67–2.79, P=0.39). Patients receiving bevacizumab had an overall incidence of all-grade ATEs of 3.3%, whereas the incidence of high-grade events was 2% in control patients118.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

It is well known that the characteristic feature of any ATE includes, disruption of unstable atherosclerotic plaques and the associated activation of platelets119. Bevacizumab might reduce anti-inflammatory effects of chronic VEGF exposure, leading to increased inflammation and atherosclerotic instability, and resulting in plaque rupture and thrombus formation120. Additionally, VEGF is important for the proliferation and repair of endothelial cells121. Therefore, anti-VEGF therapy may compromise these reparative mechanisms, leading to endothelial cell dysfunction and exposing sub-endothelial layer. As a result, the TF is activated, increasing the risk of thrombosis121. Finally, anti-VEGF therapy causes a reduction in nitric oxide and prostacyclin, as well as an increase in blood viscosity via the overproduction of erythropoietin, all of which comprise predisposing factors for increased risk of thromboembolic events as per Virchow’s triad122.

Ponatinib

The phase II PACE (ponatinib Ph+ ALL and CML evaluation) study was an open label, single-arm, multi-center trial that included patients with chronic phase CML (CP-CML), accelerated phase CML (AP-CML), blast phase CML (BP-CML), or Ph+ ALL123. This cohort comprised of patients who were either resistant or intolerant to dasatinib/nilotinib or had positive T315I mutation. While the primary and secondary endpoints were in favor of ponatinib, emergence of ATEs was an unexpected findings. Eleven percent of ponatinib developed ATEs, and the event was serious in 8% of the patients. Myocardial infarction or worsening coronary artery disease were the most common ATEs event. Furthermore, patients who experienced a serious ATEs, 62% required a revascularization procedure123. This findings were reinforced in another clinical trial. EPIC was a randomized multicenter phase III, 2-arm open-label trial of ponatinib (45 mg once daily) versus imatinib (400 mg once daily) in the newly diagnosed CP-CML. On 18 October 2013, EPIC was terminated due to the observation of arterial thrombotic events in the ponatinib development program124. In total, eleven (7%) ponatinib and three (2%) imatinib patients experienced arterial thrombotic events, designated serious for ten [7%] ponatinib and one [0.7%] imatinib patient(s). Interestingly, ten of the eleven ponatinib patients, and two of three imatinib patients with arterial thrombotic events had 1 or more cardiovascular risk factors124. This trial received a lot of notoriety as FDA asked Ariad Pharmaceuticals, makers of ponatinib, to suspend sales due the concerns regarding ponatinib’s effect on thromboembolism.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

Ponatinib, is a strong inhibitor of VEGFR1–3, which explains the high incidence of hypertension125. Furthermore, ponatinib inhibits of the angiopoietin receptor TIE-2 (KDR) and all FGFR kinases may enhance vascular toxicity126. Thus, it is believed that due to widespread inhibition of various angiogenic receptors, ponatinib, poses a greater risk of vascular toxicity leading to increased ATEs.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Dasatinib

Clinical Perspective

Dasatinib has been implicated in precipitating pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Montani et al127 reported nine cases of symptomatic PAH in a French pulmonary hypertension registry in patients treated with dasatinib for chronic myelogenous leukemia. The authors estimated that PAH occurred in 0.45% of patients taking this drug. They also reported that PAH can occur as a late complication of dasatinib therapy, occurring 8–48 months after initiation of therapy. During the initial diagnosis, most patients had severe clinical, functional and/or hemodynamic impairment. Unfortunately, some of them required vasoactive drugs and management in the intensive care unit127. Clinical and functional improvements were observed after discontinuation of the dasatinib; however, some patients required specific PAH treatment also. Acute vasodilator response was observed in only one out of nine patients, suggesting that increased vasoreactivity may not represent the main mechanism of dasatinib-induced PAH. Indeed, the majority of the patients failed to demonstrate complete hemodynamic recovery and two patients died during follow-up127.This observation is surprising because dasatinib has been shown to inhibit growth factors implicated in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Interestingly, all patients had previously received imatinib before dasatinib and six patients had received nilotinib after dasatinib discontinuation without PAH recurrence. This suggests dasatinib induced PAH is specific to this drug and is not due to a class-effect128. In October 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning regarding cardiopulmonary risks of dasatinib and recommended that patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of cardiopulmonary disease before and during dasatinib treatment129. Increased PAH incidence was also found at 36 months in the follow-up of the DASISION study (Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve CML Patients study). PAH was reported in 3% of the patients in the dasatinib group compared to 0% in imatinib130.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

The working hypothesis is that by inhibiting Src, which plays a critical role in smooth muscle cell proliferation and vasoconstriction, dasatinib alters the proliferation/ antiproliferation equilibrium at the endothelial and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle level128 resulting in hypertension. In addition, all other molecular targets specific to dasatinib might be involved, but further research must be done to understand the exact mechanisms involved.

Cyclophosphamide

Clinical Perspective

Ranchoux et al131 reviewed the French pulmonary hypertension network of all documented cases of pulmonary venous occlusive disease (PVOD) to determine the most likely chemotherapeutic agent involved. They reported that of the 179 eligible patients on PVOD, only 27 (15%) could be considered chemotherapy-induced. Of the 37 cases of chemotherapy-associated PVOD, 84% involved alkylating or alkylating-like agents. Nearly half (43%) were represented by cyclophosphamide, followed by near equal frequency of mitomycin C (24.3%) and cisplatin (21.6%) thus implicating cyclophosphamide as the most frequent contributing underlying chemotherapeutic agent for the development of PVOD131. Chemotherapy-induced PVOD was more frequent in younger patients (4 to 66 years old; 13 individuals above 50 years; median age 37.8 years) and was independent of the gender (male, 45.9%, versus female, 54.1%)131. Moreover, approximately 78% of chemotherapy-induced PVOD in the French pulmonary hypertension network presented within 1 year following the initiation of chemotherapy. This is especially ironic as cyclophosphamide is used to treat pulmonary hypertension induced by systemic lupus erythematosus132.

Potential Molecular Mechanisms

The precise mechanism is unknown. Rancheros et al131 also conducted animal research and found that mechanism involved in cyclophosphamide mediated pulmonary hypertension might be due to reduced expression of potassium channels, more specifically KCNK3. Although, corroborating evidence or elucidation of other pathways are still pending.

Conclusion

Development of cardiomyopathy, specifically with anthracycline led to the inception of onco-cardiology. Since then chemotherapy has been not only correlated to cardiomyopathies but have been implicated in other cardiovascular side-effects with significant morbidity and mortality. Early recognition, prompt intervention and active prevention will be the cornerstone of ameliorating the cardiovascular adverse events. This requires a collaborative effects of oncologists and cardiologists. This is especially important when numerous newly discovered anticancer drugs are entering the clinical trials. As we strengthen the war against cancer, we should continue to fight the battle for emerging cardiovascular disease in our oncological patients.

Supplementary Material

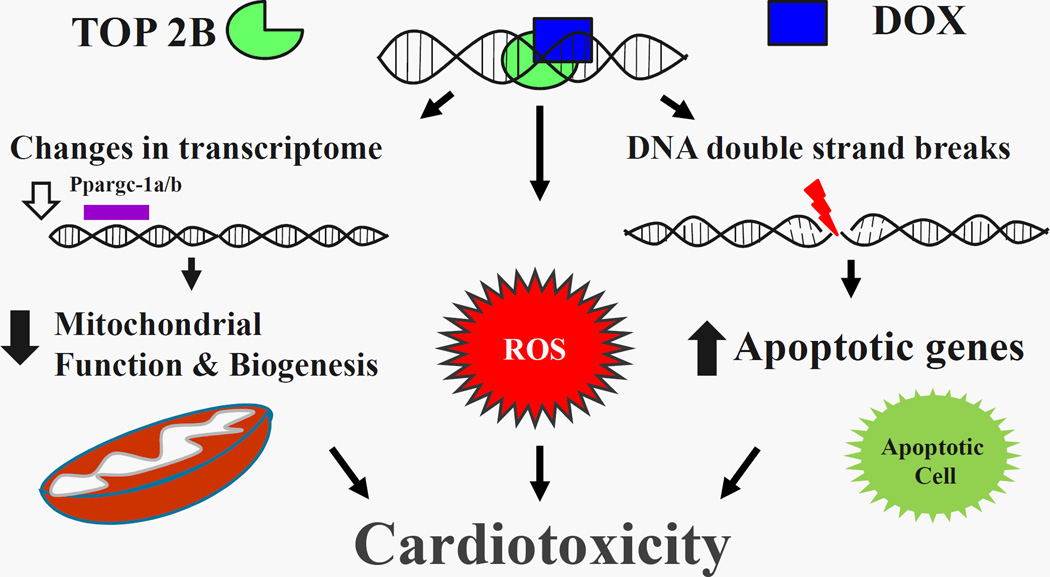

Figure 1. Schematic representation of DOX/DNA/Top II Beta ternary Complex.

Activation of the ternary complex results in double stranded DNA breaks which upregulates apoptotic signaling pathway. Furthermore, there is production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, there is downregulation of peroxisome proliferation activated receptor gamma co-activator 1 alpha and beta (Ppargc-1 α/β) which results in mitochondrial dysfunction and decreased mitochondrial biogenesis. These pathways culminates into cardiotoxicity

Table 1. Cancer Therapies Associated with Cardiac Toxicities.

Partial list of commonly used anticancer agents that have shown the corresponding cardiovascular complications.

| Commonly used Cancer Drugs with Cardiovascular Complications | ||

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure/Left Ventricular Dysfunction | ||

| Chemotherapy agents | Incidence (%) | Frequency of Use |

| Anthracyclines | ||

| Doxorubicin (Adriamycin®) | 3–26*# | ++++ |

| Epirubicin (Ellence®) | 0.9–3.3# | + |

| Idarubicin (Idamycin PFS®) | 5–18# | ++ |

| Monoclonal Antibody-based tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Adotrastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla®) | 1.8b | + |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin®) | 1–10.9 | +++ |

| Pertuzumab (Perjeta®) | 0.9–16b | + |

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin®) | 2–28b | +++ |

| Myocardial Infarction/Ischemia | ||

| Antimetabolites | ||

| Capecitabine (Xeloda®) | 3–9# | ++++ |

| Fluorouracil (Adrucil®)39–42, 44, 47, 133–136,39–42, 44, 47, 132–135 | 1–68§ | ++++ |

| Hypertension | ||

| Monoclonal Antibody-based tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Adotrastuzumab emtansine (Kadcyla®) | 5.1 | + |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin®) | 23–34# | +++ |

| mTor Inhibitors | ||

| Everolimus (Afinitor®) | 4–13 | ++++ |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel®) | 7 | ++ |

| Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Sorafenib (Nexavar®) | 9.4–41# | ++++ |

| Sunitinib (Sutent®) | 15–34# | ++++ |

| Thromboembolism | ||

| Alkylating agent | ||

| Cisplatin (Platinol-AQ®) | 8.5 | +++ |

| Angiogenesis Inhibitors | ||

| Lenalidomide (Revlimid®)1,137–142,136–141 | 3–75§b | +++ |

| Thalidomide (Thalomid®)1 | 1–58§ b | ++ |

| Pomalidomide (Pomalyst®)2,100, 143–152,99, 142–151 | 3§b | + |

| Monoclonal Antibody-based tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 6–15.1¶# | +++ |

| Bevacizumab (Avastin®)2 | ||

| Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Ponatinib (Iclusig®)2 | 5 b | + |

| Bradycardia | ||

| Angiogenesis Inhibitor | ||

| Thalidomide (Thalomid®)82, 146, 150, 153–155,81, 145, 149, 152–154,1 | 0.12–55§# | + |

| QT Prolongation | ||

| 156, 157,155, 156Miscellaneous | ||

| Arsenic trioxide (Trisenox®)87, 91, 156, 158–163,86, 90, 155, 157–162 | 26–93*# | ++ |

| Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Nilotinib (Tasigna®) | <1–4.1b | ++++ |

| Vandetanib (Caprelsa®) | 8–14b | ++++ |

At cumulative dose of 550 mg/m2

Wide variation exists in the incidence owing to different study design and definition

When used in combination with other chemotherapies

Listed as a warning/precaution in package insert

Black box warning in package insert

The frequency of use was quantified using inpatient and outpatient doses dispensed at MD Anderson Cancer Center during the time period of January 1, 2014 through December 21, 2014. (+ =<1,000 doses dispensed; ++ =1,000–5,000 doses dispensed; +++ =5,000–10,000 doses dispensed; ++++ =>10,000 doses dispensed).

Summary Title.

Cancer survivorship has seen an unprecedented increase due to the new anticancer agents. However, these drugs are marred by cardiovascular side-effect(s). This review highlights the clinical perspective and molecular mechanism(s) behind various cardio-toxic effects of some of the commonly used antineoplastic agents. The goal is to understand, delineate and ameliorate, if not to attenuate, these toxic side-effect profile of the anticancer agents.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yeh holds the Ting Tsung and Wei Fong Chao Distinguished Chair at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This work was supported in part by NIH 1-R01-HL126916-01 (Yeh) and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, RP110486-P1 (Yeh). Authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Courtney L. Meuth and Tara K. Lech for compiling the MD Anderson Cancer Center data on cancer drug usage.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For references, see online supplement.

REFRENCES

- 1.Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1215–1221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh ET, Bickford CL. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2231–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, et al. Risk factors for doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:710–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97:2869–2879. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nysom K, Holm K, Lipsitz SR, et al. Relationship between cumulative anthracycline dose and late cardiotoxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:545–550. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vandecruys E, Mondelaers V, De Wolf D, Benoit Y, Suys B. Late cardiotoxicity after low dose of anthracycline therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0186-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, Hauptmann M, et al. Cardiac function in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1247–1255. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodley A, Liu LF, Israel M, et al. DNA topoisomerase II-mediated interaction of doxorubicin and daunorubicin congeners with DNA. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5969–5978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoeffler AJ, Berger JM. DNA topoisomerases: harnessing and constraining energy to govern chromosome topology. Q Rev Biophys. 2008;41:41–101. doi: 10.1017/S003358350800468X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbett KD, Berger JM. Structure of the topoisomerase VI-B subunit: implications for type II topoisomerase mechanism and evolution. EMBO J. 2003;22:151–163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang S, Liu X, Bawa-Khalfe T, et al. Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat Med. 2012;18:1639–1642. doi: 10.1038/nm.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.L'Ecuyer T, Sanjeev S, Thomas R, et al. DNA damage is an early event in doxorubicin-induced cardiac myocyte death. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1273–H1280. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00738.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Mao W, Ding B, Liang CS. ERKs/p53 signal transduction pathway is involved in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cells and cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1956–H1965. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00407.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasinoff BB, Herman EH. Dexrazoxane: how it works in cardiac and tumor cells. Is it a prodrug or is it a drug? Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7:140–144. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-0023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman EH, el-Hage A, Ferrans VJ. Protective effect of ICRF-187 on doxorubicin-induced cardiac and renal toxicity in spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive (WKY) rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1988;92:42–53. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman EH, Ferrans VJ. Preclinical animal models of cardiac protection from anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman EH, Zhang J, Chadwick DP, Ferrans VJ. Comparison of the protective effects of amifostine and dexrazoxane against the toxicity of doxorubicin in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;45:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s002800050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman EH, Ferrans VJ. Timing of treatment with ICRF-187 and its effect on chronic doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;32:445–449. doi: 10.1007/BF00685888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao VA, Zhang J, Klein SR, et al. The iron chelator Dp44mT inhibits the proliferation of cancer cells but fails to protect from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:1125–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imondi AR. Preclinical models of cardiac protection and testing for effects of dexrazoxane on doxorubicin antitumor effects. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, Perez-Atayde AR, Sallan SE, Sanders SP. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:808–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marty M, Espie M, Llombart A, et al. Multicenter randomized phase III study of the cardioprotective effect of dexrazoxane (Cardioxane) in advanced/metastatic breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:614–622. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swain SM, Whaley FS, Gerber MC, et al. Cardioprotection with dexrazoxane for doxorubicin-containing therapy in advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1318–1332. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nitiss JL. Targeting DNA topoisomerase II in cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrc2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab--mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bird BR, Swain SM. Cardiac toxicity in breast cancer survivors: review of potential cardiac problems. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:14–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995;378:394–398. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negro A, Brar BK, Lee KF. Essential roles of Her2/erbB2 in cardiac development and function. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2004;59:1–12. doi: 10.1210/rp.59.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L, et al. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2002;8:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozcelik C, Erdmann B, Pilz B, et al. Conditional mutation of the ErbB2 (HER2) receptor in cardiomyocytes leads to dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8880–8885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122249299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, et al. Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes. Persistence of ErbB2 and ErbB4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10261–10269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilancia D, Rosati G, Dinota A, Germano D, Romano R, Manzione L. Lapatinib in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 6):vi26–vi30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenihan D, Suter T, Brammer M, Neate C, Ross G, Baselga J. Pooled analysis of cardiac safety in patients with cancer treated with pertuzumab. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:791–800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spector NL, Yarden Y, Smith B, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by human EGF receptor 2/EGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor protects cardiac cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10607–10612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hervent AS, De Keulenaer GW. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity induced by ErbB receptor inhibitor cancer therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:12268–12286. doi: 10.3390/ijms131012268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Forni M, Malet-Martino MC, Jaillais P, et al. Cardiotoxicity of high-dose continuous infusion fluorouracil: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1795–1801. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.11.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer CC, Calis KA, Burke LB, Walawander CA, Grasela TH. Symptomatic cardiotoxicity associated with 5-fluorouracil. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:729–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robben NC, Pippas AW, Moore JO. The syndrome of 5-fluorouracil cardiotoxicity. An elusive cardiopathy. Cancer. 1993;71:493–509. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930115)71:2<493::aid-cncr2820710235>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen SA, Sorensen JB. Risk factors and prevention of cardiotoxicity induced by 5-fluorouracil or capecitabine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:487–493. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Labianca R, Luporini G. 5-fluorouracil cardiotoxicity: the risk of rechallenge. Ann Oncol. 1991;2:383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labianca R, Beretta G, Clerici M, Fraschini P, Luporini G. Cardiac toxicity of 5-fluorouracil: a study on 1083 patients. Tumori. 1982;68:505–510. doi: 10.1177/030089168206800609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schober C, Papageorgiou E, Harstrick A, et al. Cardiotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil in combination with folinic acid in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:2242–2247. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2242::aid-cncr2820720730>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bertolini A, Flumano M, Fusco O, et al. Acute cardiotoxicity during capecitabine treatment: a case report. Tumori. 2001;87:200–206. doi: 10.1177/030089160108700317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosmas C, Kallistratos MS, Kopterides P, et al. Cardiotoxicity of fluoropyrimidines in different schedules of administration: a prospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anand AJ. Fluorouracil cardiotoxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:374–378. doi: 10.1177/106002809402800314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freeman NJ, Costanza ME. 5-Fluorouracil-associated cardiotoxicity. Cancer. 1988;61:36–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880101)61:1<36::aid-cncr2820610108>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frickhofen N, Beck FJ, Jung B, Fuhr HG, Andrasch H, Sigmund M. Capecitabine can induce acute coronary syndrome similar to 5-fluorouracil. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:797–801. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Porta C, Moroni M, Ferrari S, Nastasi G. Endothelin-1 and 5-fluorouracil-induced cardiotoxicity. Neoplasma. 1998;45:81–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mosseri M, Fingert HJ, Varticovski L, Chokshi S, Isner JM. In vitro evidence that myocardial ischemia resulting from 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy is due to protein kinase C-mediated vasoconstriction of vascular smooth muscle. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3028–3033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saif MW, Tomita M, Ledbetter L, Diasio RB. Capecitabine-related cardiotoxicity: recognition and management. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polk A, Vistisen K, Vaage-Nilsen M, Nielsen DL. A systematic review of the pathophysiology of 5-fluorouracil-induced cardiotoxicity. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;15:47. doi: 10.1186/2050-6511-15-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa versus interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results of CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2137–2143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, 3rd, et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:734–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–1544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2039–2045. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gordon MS, Margolin K, Talpaz M, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of recombinant human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:843–850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.An MM, Zou Z, Shen H, et al. Incidence and risk of significantly raised blood pressure in cancer patients treated with bevacizumab: an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0815-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kabbinavar FF, Schulz J, McCleod M, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3697–3705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu X, Wu S, Dahut WL, Parikh CR. Risks of proteinuria and hypertension with bevacizumab, an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:186–193. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, et al. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326–5334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yeh ET, Tong AT, Lenihan DJ, et al. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management. Circulation. 2004;109:3122–3131. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133187.74800.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Y, Fei D, Vanderlaan M, Song A. Biological activity of bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF antibody in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10456-004-8272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Camp ER, Yang A, Liu W, et al. Roles of nitric oxide synthase inhibition and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibition on vascular morphology and function in an in vivo model of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2628–2633. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mourad JJ, des Guetz G, Debbabi H, Levy BI. Blood pressure rise following angiogenesis inhibition by bevacizumab. A crucial role for microcirculation. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:927–934. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lankhorst S, Baelde HJ, Kappers MH, et al. Greater Sensitivity of Blood Pressure Than Renal Toxicity to Tyrosine Kinase Receptor Inhibition With Sunitinib. Hypertension. 2015;66:543–549. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nazer B, Humphreys BD, Moslehi J. Effects of novel angiogenesis inhibitors for the treatment of cancer on the cardiovascular system: focus on hypertension. Circulation. 2011;124:1687–1691. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.992230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maitland ML, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Initial assessment, surveillance, and management of blood pressure in patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:596–604. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robinson ES, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA, Humphreys BD. Hypertension induced by vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibition: mechanisms and potential use as a biomarker. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D'Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4082–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moreira AL, Sampaio EP, Zmuidzinas A, Frindt P, Smith KA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide exerts its inhibitory action on tumor necrosis factor alpha by enhancing mRNA degradation. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1675–1680. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barlogie B, Desikan R, Eddlemon P, et al. Extended survival in advanced and refractory multiple myeloma after single-agent thalidomide: identification of prognostic factors in a phase 2 study of 169 patients. Blood. 2001;98:492–494. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fahdi IE, Gaddam V, Saucedo JF, et al. Bradycardia during therapy for multiple myeloma with thalidomide. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1052–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meyer T, Maier A, Borisow N, et al. Thalidomide causes sinus bradycardia in ALS. J Neurol. 2008;255:587–591. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0756-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Emch GS, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits physiologically identified dorsal motor nucleus neurons in vivo. Brain Res. 2002;951:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huan SY, Yang CH, Chen YC. Arsenic trioxide therapy for relapsed acute promyelocytic leukemia: an useful salvage therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;38:283–293. doi: 10.3109/10428190009087019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohnishi K, Yoshida H, Shigeno K, et al. Prolongation of the QT interval and ventricular tachycardia in patients treated with arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:881–885. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-11-200012050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barbey JT, Pezzullo JC, Soignet SL. Effect of arsenic trioxide on QT interval in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3609–3615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schiller GJ, Slack J, Hainsworth JD, et al. Phase II multicenter study of arsenic trioxide in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2456–2464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang CH, Chen WJ, Wu CC, Chen YC, Lee YT. Complete atrioventricular block after arsenic trioxide treatment in an acute promyelocytic leukemic patient. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22:965–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb06826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Unnikrishnan D, Dutcher JP, Varshneya N, et al. Torsades de pointes in 3 patients with leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide. Blood. 2001;97:1514–1516. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Westervelt P, Brown RA, Adkins DR, et al. Sudden death among patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide. Blood. 2001;98:266–271. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ficker E, Kuryshev YA, Dennis AT, et al. Mechanisms of arsenic-induced prolongation of cardiac repolarization. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:33–44. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drolet B, Simard C, Roden DM. Unusual effects of a QT-prolonging drug, arsenic trioxide, on cardiac potassium currents. Circulation. 2004;109:26–29. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109484.00668.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Strevel EL, Ing DJ, Siu LL. Molecularly targeted oncology therapeutics and prolongation of the QT interval. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3362–3371. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, et al. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5204–5212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kloth JS, Pagani A, Verboom MC, et al. Incidence and relevance of QTc-interval prolongation caused by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1011–1016. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ghatalia P, Je Y, Kaymakcalan MD, Sonpavde G, Choueiri TK. QTc interval prolongation with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:296–305. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sanguinetti MC, Mitcheson JS. Predicting drug-hERG channel interactions that cause acquired long QT syndrome. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Obers S, Staudacher I, Ficker E, et al. Multiple mechanisms of hERG liability: K+ current inhibition, disruption of protein trafficking, and apoptosis induced by amoxapine. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;381:385–400. doi: 10.1007/s00210-010-0496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rajkumar SV, Hayman S, Gertz MA, et al. Combination therapy with thalidomide plus dexamethasone for newly diagnosed myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4319–4323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zangari M, Anaissie E, Barlogie B, et al. Increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma receiving thalidomide and chemotherapy. Blood. 2001;98:1614–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zangari M, Siegel E, Barlogie B, et al. Thrombogenic activity of doxorubicin in myeloma patients receiving thalidomide: implications for therapy. Blood. 2002;100:1168–1171. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Desai AA, Vogelzang NJ, Rini BI, Ansari R, Krauss S, Stadler WM. A high rate of venous thromboembolism in a multi-institutional phase II trial of weekly intravenous gemcitabine with continuous infusion fluorouracil and daily thalidomide in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1629–1636. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zangari M, Barlogie B, Anaissie E, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma treated with thalidomide and chemotherapy: effects of prophylactic and therapeutic anticoagulation. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:715–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Minnema MC, Fijnheer R, De Groot PG, Lokhorst HM. Extremely high levels of von Willebrand factor antigen and of procoagulant factor VIII found in multiple myeloma patients are associated with activity status but not with thalidomide treatment. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:445–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kaushal V, Kohli M, Zangari M, Fink L, Mehta P. Endothelial dysfunction in antiangiogenesis-associated thrombosis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.13.3042. author reply 3042–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weijl NI, Rutten MF, Zwinderman AH, et al. Thromboembolic events during chemotherapy for germ cell cancer: a cohort study and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2169–2178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Numico G, Garrone O, Dongiovanni V, et al. Prospective evaluation of major vascular events in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine. Cancer. 2005;103:994–999. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jacobson GM, Kamath RS, Smith BJ, Goodheart MJ. Thromboembolic events in patients treated with definitive chemotherapy and radiation therapy for invasive cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Apiyasawat S, Wongpraparut N, Jacobson L, Berkowitz H, Jacobs LE, Kotler MN. Cisplatin induced localized aortic thrombus. Echocardiography. 2003;20:199–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2003.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Seng S, Liu Z, Chiu SK, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer treated with Cisplatin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4416–4426. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Walsh J, Wheeler HR, Geczy CL. Modulation of tissue factor on human monocytes by cisplatin and adriamycin. Br J Haematol. 1992;81:480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb02978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Togna GI, Togna AR, Franconi M, Caprino L. Cisplatin triggers platelet activation. Thromb Res. 2000;99:503–509. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cool RM, Herrington JD, Wong L. Recurrent peripheral arterial thrombosis induced by cisplatin and etoposide. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:1200–1204. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.13.1200.33524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Licciardello JT, Moake JL, Rudy CK, Karp DD, Hong WK. Elevated plasma von Willebrand factor levels and arterial occlusive complications associated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Oncology. 1985;42:296–300. doi: 10.1159/000226049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scappaticci FA, Skillings JR, Holden SN, et al. Arterial thromboembolic events in patients with metastatic carcinoma treated with chemotherapy and bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1232–1239. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kozloff M, Yood MU, Berlin J, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with bevacizumab-containing treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the BRiTE observational cohort study. Oncologist. 2009;14:862–870. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ranpura V, Hapani S, Chuang J, Wu S. Risk of cardiac ischemia and arterial thromboembolic events with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:287–297. doi: 10.3109/02841860903524396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nieswandt B, Pleines I, Bender M. Platelet adhesion and activation mechanisms in arterial thrombosis and ischaemic stroke. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kuenen BC, Levi M, Meijers JC, et al. Analysis of coagulation cascade and endothelial cell activation during inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor pathway in cancer patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1500–1505. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000030186.66672.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1788–1795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kilickap S, Abali H, Celik I. Bevacizumab, bleeding, thrombosis, and warfarin. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.046. author reply 3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al. A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1783–1796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lipton JH, Chuah C, Guerci-Bresler A, et al. Epic: A Phase 3 Trial of Ponatinib Compared with Imatinib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase (CP-CML) (abstract); 56th American Society of Hematology Meeting; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhu X, Stergiopoulos K, Wu S. Risk of hypertension and renal dysfunction with an angiogenesis inhibitor sunitinib: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:9–17. doi: 10.1080/02841860802314720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.O'Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:401–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Montani D, Bergot E, Gunther S, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients treated by dasatinib. Circulation. 2012;125:2128–2137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.079921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pullamsetti SS, Berghausen EM, Dabral S, et al. Role of Src tyrosine kinases in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1354–1365. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Moslehi JJ, Deininger M. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor-Associated Cardiovascular Toxicity in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Saglio G, et al. Early response with dasatinib or imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: 3-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION) Blood. 2014;123:494–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-511592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ranchoux B, Gunther S, Quarck R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced pulmonary hypertension: role of alkylating agents. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:356–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Groen H, Bootsma H, Postma DS, Kallenberg CG. Primary pulmonary hypertension in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: partial improvement with cyclophosphamide. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:1055–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Singer M. Cardiotoxicity and capecitabine: a case report. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7:72–75. doi: 10.1188/03.CJON.72-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Van Cutsem E, Hoff PM, Blum JL, Abt M, Osterwalder B. Incidence of cardiotoxicity with the oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine is typical of that reported with 5-fluorouracil. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:484–485. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pai VB, Nahata MC. Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents: incidence, treatment and prevention. Drug Saf. 2000;22:263–302. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200022040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rezkalla S, Kloner RA, Ensley J, et al. Continuous ambulatory ECG monitoring during fluorouracil therapy: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:509–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]