Abstract

BACKGROUND

Red cell distribution width (RDW) is an index of red blood cell volume variability that has historically been used as a marker of iron-deficiency anemia. More recently, studies have shown that elevated RDW is associated with higher mortality risk in the general population. However, there is lack of data demonstrating the association between RDW and mortality risk in hemodialysis (HD) patients. We hypothesized that higher RDW levels are associated with higher mortality in HD patients.

STUDY DESIGN

Retrospective observational study using a large HD patient cohort.

SETTING & PARTICIPANTS

109,675 adult maintenance HD patients treated in a large dialysis organization January 1, 2007–December 31, 2011.

PREDICTOR

Baseline and time-varying RDW, grouped into 5 categories: <14.5%, 14.5%–<15.5%, 15.5%–<16.5%, 16.5%–<17.5% and ≥ 17.5%. RDW 15.5%–<16.5% was used as the reference category.

OUTCOME

All-cause mortality.

RESULTS

The mean age of study participants was 63±15 (SD) years and the study cohort was 44% female. In baseline and time-varying analyses, there was a graded association between higher RDW levels and incrementally higher mortality risk. Receiver operating characteristic, net reclassification analysis and integrated discrimination improvement analyses demonstrated that RDW is a stronger predictor of mortality as compared with traditional markers of anemia such as hemoglobin, ferritin, and iron saturation.

LIMITATIONS

Lack of comprehensive data that may be associated with both RDW and HD patient outcomes, such as blood transfusion data, socioeconomic status, and other unknown confounders; therefore the possibility of residual confounding could not be excluded. Also, lack of information on cause of death; thus, cardiovascular mortality outcomes could not be examined.

CONCLUSIONS

In HD patients, higher RDW levels are associated with incrementally higher mortality risk. RDW is also a stronger predictor of mortality than traditional laboratory markers of anemia. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms underlying the association between RDW and mortality.

Keywords: Red cell distribution width (RDW), red blood cell heterogeneity, hemodialysis (HD), mortality, renal function, end-stage renal disease (ESRD)

Red cell distribution width (RDW) is a quantitative marker of heterogeneity of red blood cell (RBC) volume1. It is routinely reported as a part of the standard complete blood count. While it has traditionally been considered to be a marker of nutritional deficiency (iron, vitamin B12 and folate),2 in more recent years RDW has emerged as a novel predictor of mortality across various populations3–12. While the underlying mechanism of the RDW-mortality association remains unclear, it has been hypothesized that it may also be a marker of malnutrition and inflammation.

While RDW has been shown to closely correlate with kidney function1,13–15 there is limited understanding of the relationship between RDW and mortality in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, particularly in those receiving dialysis. To date, only two small studies in peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD) patients have examined this question. In the first of these studies, amongst 1293 incident PD patients from a single center, those with an RDW ≥ 15.5% had a 60% and 27% higher cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risk, respectively, compared to those with an RDW <15.5%.13 In the second prospective study of 100 HD patients from a single center, each 1% increase in RDW level was associated with a 54% higher all-cause mortality risk after one-year follow up in crude analyses.15

Given the limited generalizability and lack of adjustment of potential confounders in the aforementioned studies, we sought to re-examine the association between RDW and mortality in a nationally representative population of HD patients receiving care from a large dialysis provider in the United States. We hypothesized that higher RDW levels are associated with higher mortality risk in HD patients independent of socio-demographics, co-morbidities, laboratory confounders, and that RDW may have strong predictive value as a marker of mortality.

METHODS

Source Cohort

The study was approved by the institutional review committees of the University of California Irvine, University of Washington, and DaVita Clinical Research (UCI IRB# 2012–9090). The study was exempt from informed written consent due to its nonintrusive nature and anonymity of patients.

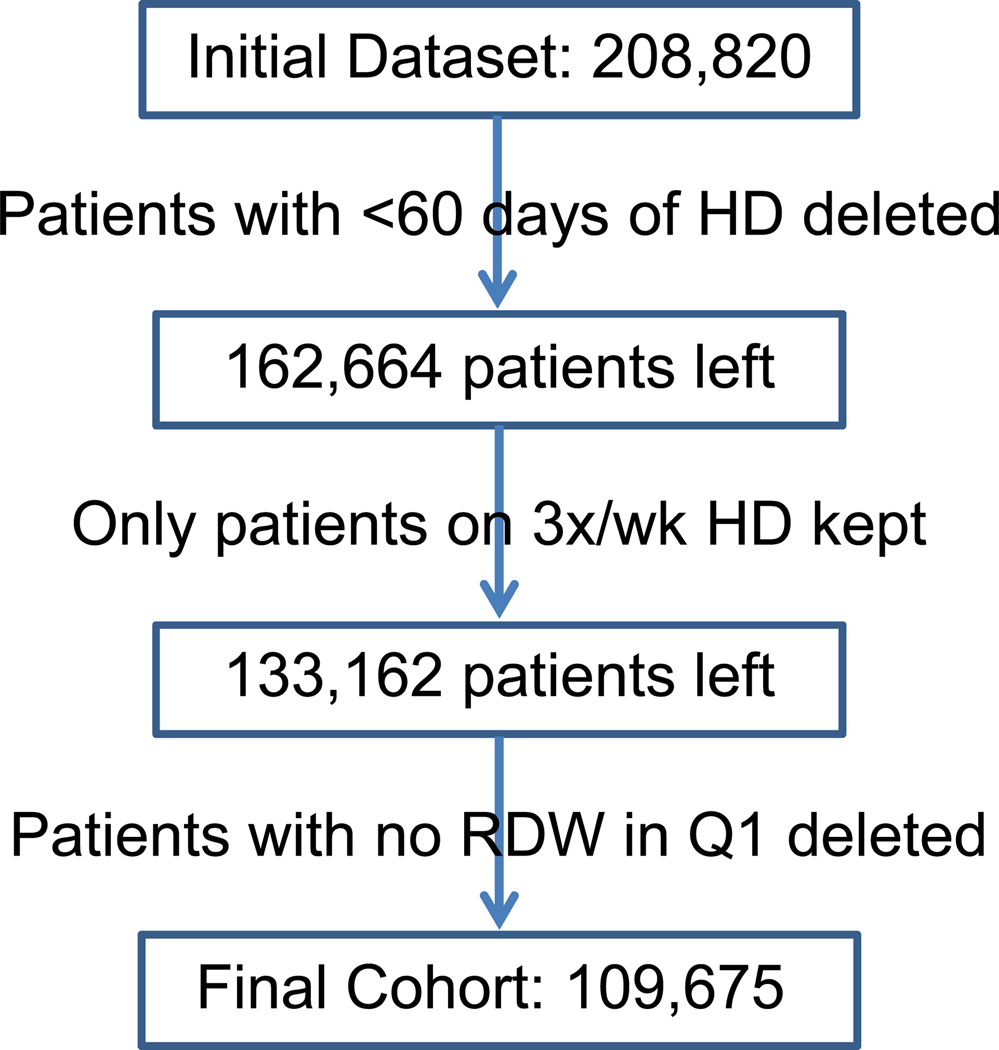

We examined the data from a total of 208,820 patients with end stage renal disease who initiated dialysis therapy from January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2011, in a large dialysis care organization in the United States. We excluded 46,156 patients among whom dialysis vintage was less than 60 days total; 29,502 patients who were not initiated on thrice-a-week HD; and 23,487 patients who did not have RDW measured during the first three months of initiating dialysis. The final study population consisted of 109,675 adult HD patients (Figure 1). Patients were followed up from the date of dialysis initiation until death, kidney transplantation, transfer to another dialysis facility, or end of the study period (December 31, 2011), whichever occurred first.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection.

Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Laboratory Measures

Information on socio-demographics, dialysis modality, vascular access type, cause of end stage renal disease, hospitalization data, co-morbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, other cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, history of cancer, human immunodeficiency virus and dyslipidemia), body weight, laboratory values, and intravenous medications were obtained from the large dialysis organization database.

In all large dialysis care organization clinics, blood samples were drawn using standardized techniques and were transported to a centralized laboratory in Deland, Florida, typically within 24 hours, where they were measured using automated and standardized methods. Serum creatinine, phosphorus, calcium, serum urea nitrogen, albumin, bicarbonate, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and RDW were measured monthly. Serum intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) and ferritin were measured at least quarterly. Hemoglobin was measured weekly to bi-weekly in most patients. Delivered dialysis dose was estimated by single-pooled Kt/V using the urea kinetic model. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as post-HD body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Data were averaged over 91-day intervals from dialysis initiation (dialysis patient quarters). Measurements during the first 91 days on dialysis were used as baseline values.

The RDW was routinely reported along with complete blood count and was calculated by dividing the standard deviation of the mean cell size by the mean cell volume of the red cells and multiplying by 100 to convert to a percentage. The reference range for RDW is approximately 11.5%–15.5%16

Statistical Methods

Descriptive data were summarized using proportions, means ±standard deviation, and medians (interquartile range [IQR]) as appropriate, and were compared using tests for trend, analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric variables) or chi-square tests.

Linear regression was used to calculate expected change in baseline RDW with each unit change in a laboratory variable and correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the strength of these associations.

The relationship between baseline and time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality was examined using Cox proportional hazard models. The RDW was categorized into 5 different groups (<14.5%, 14.5 %–< 15.5%, 15.5 %–< 16.5%, 16.5 %–< 17.5% and ≥ 17.5%). The RDW category 15.5 %–< 16.5% was used as reference category as it was the category with the largest proportion of patients. Three levels of adjustment were analyzed: 1) unadjusted models that included RDW, the main predictor variable; 2) case-mix adjusted models that additionally included age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, African American, Hispanic, Asian and other), comorbidities, cause of end stage renal disease, dialysis access, primary insurance, delivered dialysis dose and number of days in hospital per dialysis patient quarter; and 3) case-mix plus malnutrition inflammation complex syndrome (MICS)–adjusted models which included all of the covariates in the case-mix model as well as 17-surrogates of nutritional and inflammatory status: hemoglobin, serum albumin, calcium, phosphorus, iPTH, iron saturation, TIBC, ferritin, bicarbonate, white blood cell (WBC) count, lymphocyte percentage, creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, BMI, normalized protein catabolic rate, cumulative iron dose per quarter, and erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) median dose per week. Time-varying models included time updated values of dialysis dose, number of hospital days per dialysis patient quarter, and all MICS laboratory measurements. Associations of RDW as a continuous predictor with mortality were also modeled using restricted cubic splines with best placed knots at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. We examined possible effect modification in the baseline RDW-mortality association across strata of demographics, comorbidities and laboratory measurements with higher baseline RDW ≥15.5% versus lower referent RDW<15.5%.

The added value of RDW to case-mix covariates in predicting all-cause mortality was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROCs) analysis with area under the curve (AUC). This was compared with ROCs of other markers of anemia (i.e., hemoglobin, iron saturation, ferritin) and albumin as it is a strong predictor of mortality. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare goodness-of-fit of case-mix models to case-mix models with the added predictor. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) was performed to examine the effect of case mix variables alone versus case mix variables and RDW on different cut-off points (5%, 15%, 30%) in predicting all-cause mortality. We also calculated integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) to compare the discrimination ability between the two logistic regression prediction models (case mix variables alone versus case mix variables and RDW). The NRI and IDI were also calculated for other markers of anemia (i.e., hemoglobin, iron saturation, ferritin) and albumin.

In the primary analysis, data was missing for 1.3%, 4.6% and 1.5% of patients for serum ferritin, creatinine and normalized protein catabolic rate, respectively, and data was missing for <1% for all other covariates. In sensitivity analysis, data on vitamin B12 and folate was missing for 88% and 87% of patients, respectively. For all analyses, complete case methods were used, where each model analysis was limited to patients with complete data for all model variables. All analyses were carried out with Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics According to RDW

The cohort included 109,675 HD patients. Baseline characteristics stratified by the five RDW categories are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 63±15 (standard deviation) years old. At baseline, patients with higher RDW were more likely to be African American, have diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, and use a central venous catheter at time of initiation of hemodialysis. As RDW increased, serum ferritin, vitamin B12 and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels increased whereas iPTH levels decreased. Interestingly, hemoglobin, ESA and iron dose were essentially similar across all groups of RDW.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by RDW

| Total | RDW | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <14.5% | 14.5%– <15.5% |

15.5%– <16.5% |

16.5%– <17.5% |

≥17.5% | |||

| No. of participants | 109,675 (100) | 12,704 (12) | 24,973 (23) | 27,852 (25) | 20,260 (18) | 23,886 (22) | |

| Age, y | 63±15 | 59±15 | 61±15 | 63±15 | 64±15 | 64±15 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 47,761(44) | 3,850(30) | 9,766(39) | 12,261(44) | 9,733(48) | 12,151(51) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 64,060(58) | 6,755(53) | 14,856(59) | 16,654(60) | 12,058(60) | 13,737(58) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||||

| Caucasian | 51,124(47) | 5,777(46) | 11,374(46) | 13,183(47) | 9,609(48) | 11,181(47) | |

| African American | 34,366(31) | 3,192(25) | 6,750(27) | 8,419(31) | 6,917(34) | 9,088(38) | |

| Hispanic | 16,334(15) | 2,582(20) | 4,783(19) | 4,310(15) | 2,448(12) | 2,211(9) | |

| Asian | 3,530(3) | 500(4) | 906(4) | 875(3) | 590(3) | 659(3) | |

| Other | 3,977(4) | 603(5) | 1,063(4) | 982(4) | 637(3) | 692(3) | |

| Insurance | <0.001 | ||||||

| Medicare | 58,859(54) | 5,977(47) | 12,693(51) | 14,947(54) | 11,367(56) | 13,875(58) | |

| Medicaid | 7,647(7) | 1,068(8) | 1,803(7) | 1,931(7) | 1,339(7) | 1,506(6) | |

| Other | 43,169(39) | 5,659(45) | 10,477(42) | 10,974(39) | 7,554(37) | 8,505(36) | |

| Single-pool Kt/V | 1.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 0.004 |

| URR | 68±7 | 68±7 | 68±7 | 68±7 | 69±7 | 69±7 | 0.008 |

| Co-morbidities | |||||||

| ASHD | 15,773(14) | 1,418(11) | 3,176(13) | 4,050(15) | 3,133(15) | 3,996(17) | <0.001 |

| CHF | 40,339(37) | 3,875(31) | 8,582(34) | 10,345(37) | 7,888(39) | 9,649(40) | <0.001 |

| Other CVD | 16,643(15) | 1,424(11) | 3,277(13) | 4,141(15) | 3,378(17) | 4,423(19) | <0.001 |

| CBVD | 1,942 (2) | 179(1) | 440(2) | 500(2) | 360(2) | 463(2) | <0.001 |

| HTN | 56,153(51) | 6,340(50) | 12,617(51) | 14,163(51) | 10,492(52) | 12,541(53) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 5,595(5) | 447(4) | 1,079(4) | 1,457(5) | 1,136(6) | 1,476(6) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 2,538(2) | 206(2) | 427(2) | 584(2) | 527(3) | 794(3) | <0.001 |

| HIV | 543 (0.5) | 44(0.3) | 59(0.2) | 95(0.3) | 119(0.6) | 226(1.0) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 27,709(25) | 2,908(23) | 6,091(24) | 7,123(26) | 5,180(26) | 6,407(27) | <0.001 |

| Access type | <0.001 | ||||||

| CVC | 81,966(75) | 8,494(67) | 18,215(73) | 21,000(75) | 15,567(77) | 18,690(78) | |

| AV Fistula | 16,389(15) | 2,957(24) | 4,350(18) | 4,055(15) | 2,494(13) | 2,533(11) | |

| AV Graft | 4,545(4) | 551(4) | 1,037(4) | 1,121(4) | 868(4) | 968(4) | |

| AV other | 105(0.09) | 15(0.10) | 30(0.10) | 16(0.05) | 26(0.1) | 18(0.07) | |

| Unknown | 6,583(6) | 678(5) | 1,320(5) | 1,632(6) | 1,289(6) | 1,664(7) | |

| Cause of ESRD | <0.001 | ||||||

| Diabetes | 50,350(46) | 6,157(48) | 12,532(50) | 13,328(49) | 8,886(43) | 9,447(40) | |

| HTN | 32,513(30) | 3,644(29) | 7,120(29) | 8,111(29) | 6,219(31) | 7,419(31) | |

| GN | 10,155(9) | 1,026(8) | 1,853(7) | 2,404(9) | 2,001(10) | 2,871(12) | |

| Cystic Kidney Disease | 1,642(1) | 401(3) | 433(2) | 379(1) | 215(1) | 214(1) | |

| Other | 15,015(14) | 1,476(12) | 3,035(12) | 3,630(12) | 2,939(15) | 3,935(16) | |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.5±0.5 | 3.7±0.5 | 3.8±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 | 3.4±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.09±0.6 | 9.05±0.5 | 9.05±0.6 | 9.08±0.6 | 9.12±0.6 | 9.18±0.6 | <0.001 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 4.9±1.2 | 5.0±1.1 | 5.0±1.1 | 5.0±1.2 | 4.9±1.2 | 4.8±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 283 (164, 486) | 249 (153, 402) | 266 (159, 434) | 283 (166, 478) | 303 (170, 529) | 315 (171, 584) | <0.001 |

| iPTH (pg/ml) | 313 (197, 486) | 339 (222, 507) | 330 (216, 503) | 315 (198, 487) | 301 (187, 472) | 286 (174, 460) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.1±1.2 | 11.4±1.1 | 11.3±1.1 | 11.1±1.1 | 10.9±1.2 | 10.8±1.3 | <0.001 |

| WBC (×103/mm3) | 7.8±2.7 | 7.5±2.1 | 7.7±2.3 | 7.8±2.4 | 7.9±2.8 | 8.0±3.3 | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 1.5 (0.6,3.6) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.6) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.4) | 1.3 (0.6, 3.6) | 2.0(0.8, 5.2) | 2.4 (1, 4.7) | <0.001 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 87 (69, 115) | 80 (65, 101) | 84 (67, 108) | 86 (69, 113) | 90 (70, 120) | 95 (74, 130) | <0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 23.6±2.7 | 23.4±2.6 | 23.4±2.6 | 23.4±2.7 | 23.6±2.7 | 23.8±2.8 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 5.5 (4.2, 7.1) | 5.7 (4.5, 7.3) | 5.6 (4.4, 7.3) | 5.5 (4.2, 7.1) | 5.3 (4.1, 7.1) | 5.2 (3.9, 6.8) | <0.001 |

| TIBC (µg/dl) | 225±49 | 241±43 | 231±45 | 224±47 | 219±50 | 214±54 | <0.001 |

| Iron Saturation, % | 23.0±9.1 | 24.4±8.2 | 23.0±7.9 | 22.4±8.2 | 22.6±9.1 | 23.9±11.4 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/ml) | 638 (454, 930) | 579 (424, 830) | 609 (440, 889) | 631 (451, 917) | 664 (484, 962) | 684 (481, 1015) | <0.001 |

| Folate (ng/ml) | 14.4 (8.5, 20.0) | 13.2 (8.2, 20) | 13.8 (8.2, 20.0) | 13.9 (8.3, 20.0) | 14.7 (8.5, 20.0) | 15.9 (8.9, 20.0) | <0.001 |

| ESA dose, IU/wk | 4692 (1493, 11931) | 4401 (1307, 11104) | 4444 (1429, 11413) | 4620 (1437, 11727) | 4800 (1500, 12099) | 5135 (1666, 12949) | <0.001 |

| Iron dose in Q1 (IU) | 1000 (400, 1400) | 950 (450, 1350) | 1000 (500, 1400) | 1000 (450, 1500) | 1000 (450, 1450) | 900 (250, 1400) | <0.001 |

| nPCR (g/kg/d) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (23, 32) | 27 (24, 32) | 27 (23, 32) | 27 (23, 32) | 26 (23, 32) | 26 (22, 31) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte, % | 20.7±7.5 | 22.8±7.0 | 21.5±7.1 | 20.7±7.2 | 20.1±7.5 | 19.2±8.3 | <0.001 |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables are given as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed or median [interquartile range] if skewed. Conversion factors for units: calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.2495; creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, ×88.4; phosphorus in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.3229; TIBC in µg/dL to µmol/L, ×0.179; folate in ng/mL to nmol/L, ×2.266

Abbreviations: URR, urea reduction ratio; ASHD, atherosclerotic heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HTN, hypertension; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CKD, cystic kidney disease; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; WBC, white blood cell;; CRP, C reactive protein; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; BMI, body mass index; RDW, red cell distribution width; CBVD, cerebrovascular disease; AV, arteriovenous; GN, glomerulonephritis; Q1, first quarter (of year); ; ALP, alkaline phosphatase

Association of RDW With Different Laboratory Variables

Table 2 shows the correlation and association between RDW and different laboratory variables. The RDW had positive correlation with ferritin, WBC, CRP, iron saturation, bicarbonate, median ESA dose, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, single-pool Kt/V, vitamin B12 and folate. It had a negative correlation with albumin, platelet, creatinine, hemoglobin, phosphorus, iPTH, BMI, lymphocyte, TIBC, and iron dose. However, these correlations between RDW and various laboratory variables were weak. The strongest correlation was found to be between RDW and albumin. With every 1 g/dl increase in albumin, RDW decreased by 0.7% (correlation coefficient, −0.20).

Table 2.

Correlations and linear regressions of baseline RDW with various laboratory data

| Laboratory variable | Coefficient (95% CI) | Correlation (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Albumin, per 1-g/dl greater | −0.731 (−0.752 to −0.710) | −0.200 (−0.207 to −0.193) |

| Ferritin, per 100 ng/ml greater | 0.060 (0.057 to 0.062) | 0.135 (0.128 to 0.142) |

| Platelet, per 10,000 cells/mm3 greater | −0.009 (−0.011 to – 0.007) | −0.049 (−0.062 to −0.036) |

| WBC Count, per 1000 cells/ mm3 greater | 0.040 (0.036 to 0.043) | 0.060 (0.054 to 0.066) |

| nPCR, per 1 g/kg/d greater | −0.470 (−0.520 to −0.430) | −0.059 (−0.064 to −0.053) |

| CRP, per 1 mg/L greater | 0.050 (0.030 to 0.090) | 0.149 (0.088 to 0.210) |

| Hemoglobin, per 1 g/dl greater | −0.250 (−0.260 to −0.240) | −0.172 (−0.178 to −0.167) |

| Iron Saturation, per 1% greater | 0.004 (0.003 to 0.005) | 0.021 (0.014 to 0.029) |

| Phosphorus, per 1 mg/dl greater | −0.100 (−0.108 to −0.090) | −0.065 (−0.071 to −0.060) |

| iPTH, per 100 pg/ml greater | −0.020 (−0.023 to −0.017) | −3.8 (−4.4 to −3.3) |

| BMI, per 1 kg/m2 greater | −0.012 (−0.013 to −0.010) | −0.049 (−0.055 to −0.043) |

| Bicarbonate, per 1-meq/L greater | 0.036 (0.030 to 0.040) | 0.055 (0.050 to 0.061) |

| Lymphocyte, per 1% greater | −0.034 (−0.035 to −0.033) | −0.146 (−0.153 to −0.139) |

| TIBC, per 1 µg/dl greater | −0.006 (−0.006 to −0.005) | −0.161 (−0.168 to −0.154) |

| Median ESA dose, per 1000 IU greater | 0.004 (0.003 to 0.005) | 0.028 (0.023 to 0.033) |

| Iron dose, per 100 IU greater | −0.007 (−0.008 to −0.005) | −0.028 (−0.035 to −0.022) |

| Creatinine, per 1 mg/dl greater | −0.061 (−0.065 to −0.056) | −0.082 (−0.087 to −0.077) |

| Calcium, per 1 mg/dl greater | 0.275 (0.257 to 0.293) | 0.089 (0.083 to 0.094) |

| ALP, per 1 IU/L greater | 0.003 (0.003 to 0.003) | 0.133 (0.126 to 0.140) |

| Single-pool Kt/V, per 1 U greater | 0.001 (−0.030 to 0.032) | 0.002 (−0.006 to 0.007) |

| Vitamin B12, per 100 pg/ml greater | 0.036 (0.030 to 0.043) | 0.091 (0.074 to 0.109) |

| Folate, per 1 ng/ml greater | 0.0179 (0.013 to 0.023) | 0.061 (0.045 to 0.077) |

Note: Conversion factors for units: calcium in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.2495; creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, ×88.4; phosphorus in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.3229; TIBC in µg/dL to µmol/L, ×0.179; folate in ng/mL to nmol/L, ×2.266

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; RDW, red cell distribution width; TIBC, total iron-binding capacity; ALP, alkaline phosphatase

Association of RDW With Mortality

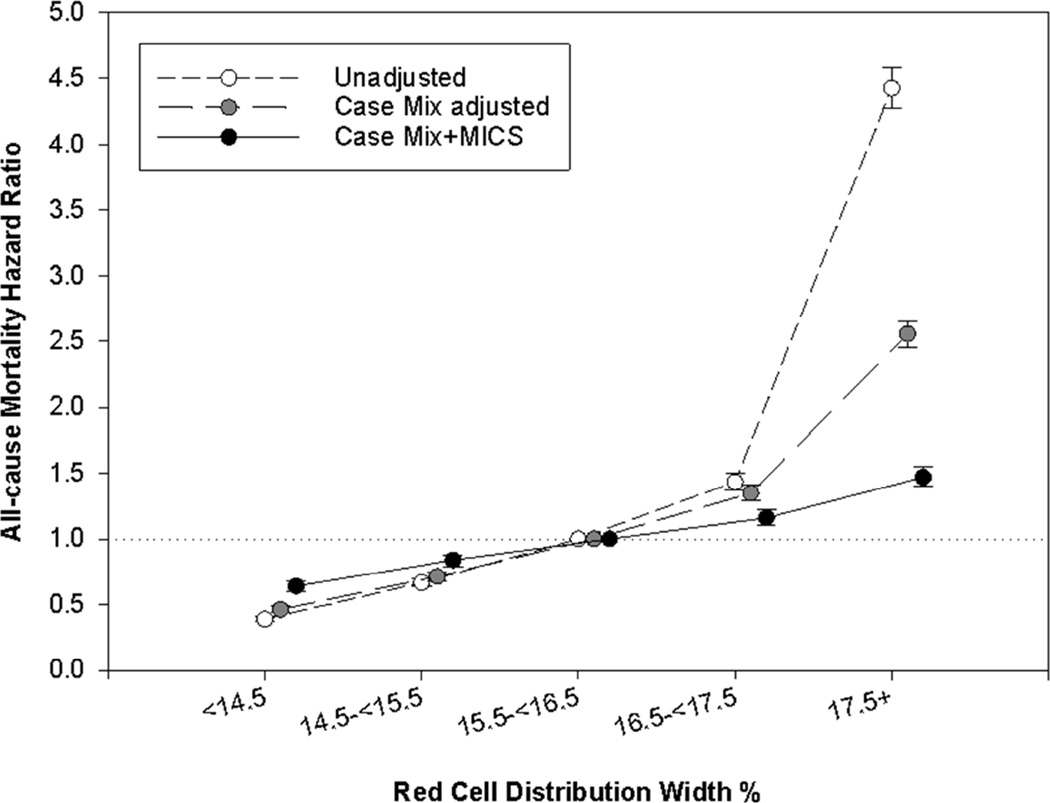

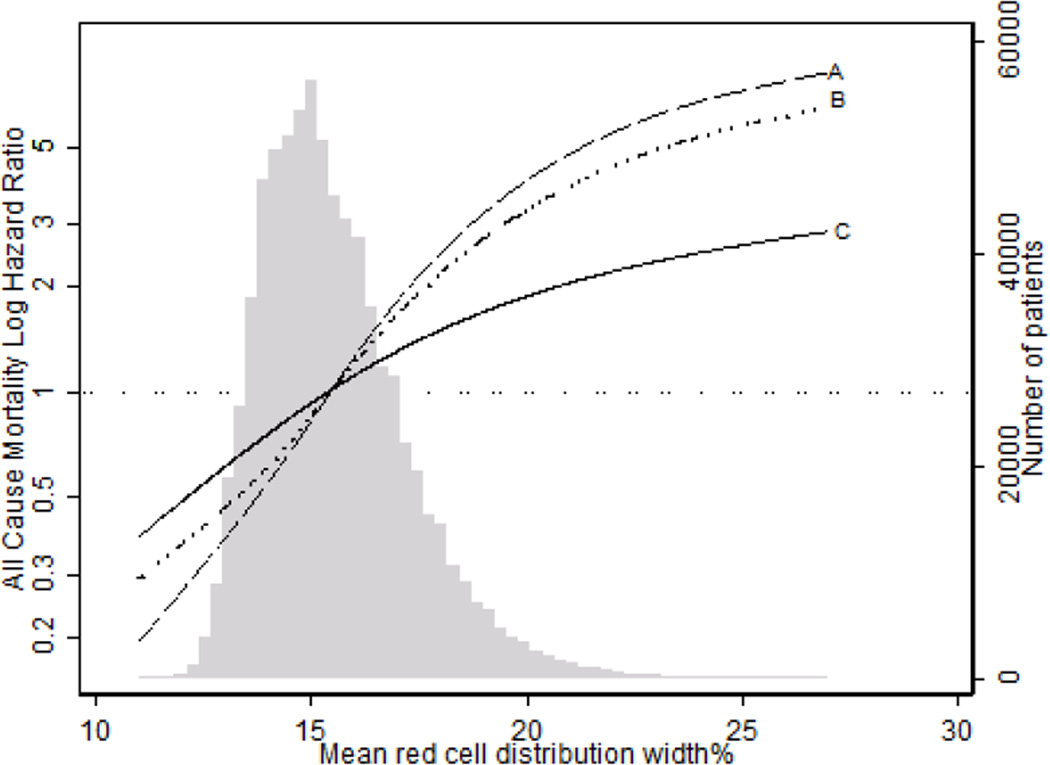

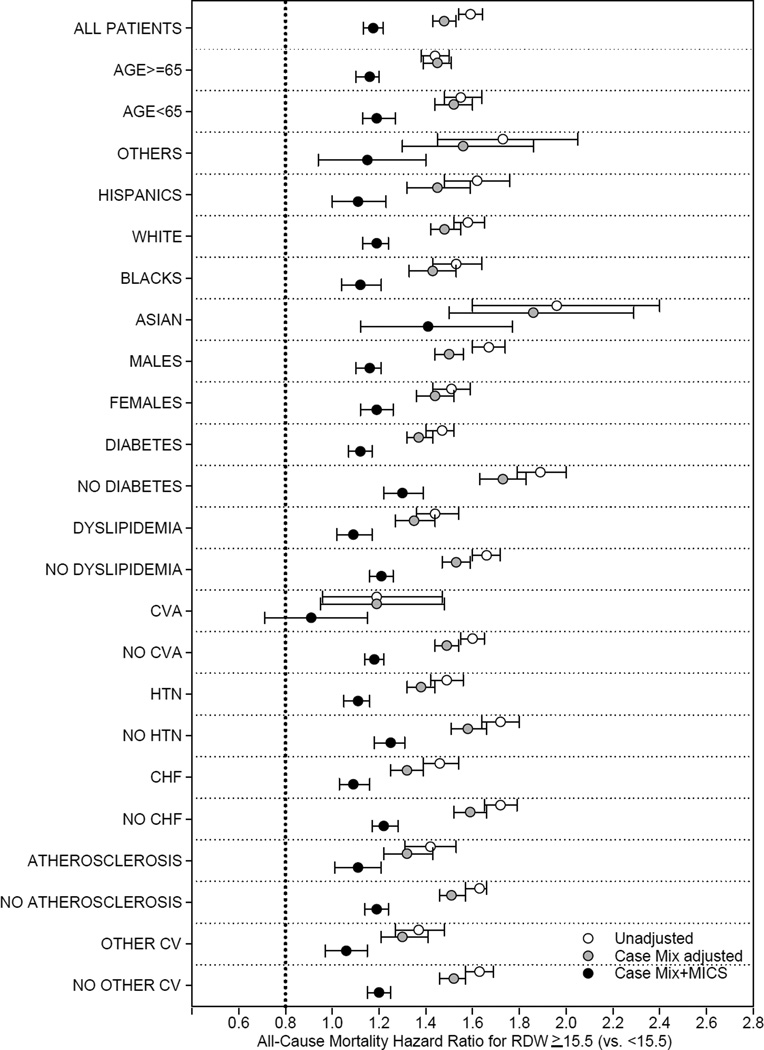

Using RDW 15.5%–<16.5% as a reference, there was a linear association between baseline RDW and mortality in unadjusted, case-mix–adjusted and case-mix-plus-MICS–adjusted models. In case-mix-plus-MICS models, baseline RDW ≥17.5% was associated with the highest risk for mortality when compared to the reference group (15.5%–<16.5%; adjusted hazard ratio [HRs], 1.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–1.33; Fig 2, Table S1 [provided as online supplementary material]). Higher time-varying RDW was incrementally associated with higher all-cause mortality risk in all levels of adjustment (Figures 3, 4; Table S2). In the fully adjusted case-mix plus MICS model, lower time-varying RDW groups of < 14.5% and 14.5%–<15.5% were associated with lower mortality risk compared to the reference group (adjusted HRs of 0.64 [95% CI, 0.60–0.68] and 0.84 [95% CI, 0.79–0.88], respectively), while higher time-varying RDW groups of 16.5%–<17.5% and ≥17.5% were associated with higher mortality risk (adjusted HRs of 1.16 [95% CI, 1.10–1.22] and 1.47 [95% CI, 1.40–1.55], respectively). Subgroup analyses demonstrated that patients with RDW ≥15.5 % had a higher all cause mortality in unadjusted, case mix adjusted and case mix plus MICS adjusted models as compared to patients with RDW <15.5% (Figures 5–6).

Figure 2.

Association of baseline RDW with all cause mortality over 5 years of follow up.

Figure 3.

Association of time varying RDW with all cause mortality over 5 years of follow up.

Figure 4.

Spline showing association of time varying RDW with all cause mortality over 5 years of follow up (A- Unadjusted model, B- Case Mix adjusted, C- Case Mix plus MICS adjusted)

Figure 5.

Subgroup analyses demonstrating all cause mortality hazard ratio in patients with Baseline RDW ≥ 15.5% (RDW <15.5% as reference group), by demographics and comorbid conditions

Figure 6.

Subgroup analyses demonstrating all cause mortality hazard ratio in patients with Baseline RDW ≥ 15.5% (RDW <15.5% as reference group), by laboratory values.

Predictive Value of RDW

The ROC analysis demonstrated a modest improvement in AUC after adding RDW to the case-mix model in predicting mortality within the first year of initiating dialysis (AUC of 0.734 [95% CI, 0.730–0.739] versus 0.763 [95% CI, 0.758–0.767] without and with RDW, respectively). Similarly, adding albumin to the case-mix model changed the AUC from 0.734 (95% CI, 0.730–0.739) to 0.758 (95% CI, 0.753–0.762). The AUC remained unchanged after adding hemoglobin, ferritin and percent iron saturation to case-mix models individually (Table 3). Using IDI, the discrimination slope of the case mix with RDW model was 1.8% and 2.5% higher when compared to the case mix model alone in predicting 1 and 5 year mortality, respectively. Reclassification analysis for all-cause mortality using NRI showed an improvement after adding RDW to the model (cutoff < 5%, 5%–<15%, 15%–30% and >30%: NRIs of 13.9% [95% CI, 13.0%–14.9%] and 13.6% [95% CI, 12.9%–14.2%] for 1-year and 5-year mortality, respectively; p <0.001; Table 4). In the same model, albumin had the highest predictive value for all-cause mortality, and all other markers of anemia (e.g., ferritin, hemoglobin and iron saturation) had much lower predictive ability when compared to RDW. Reclassification table for models without and with RDW as a predictor of event (event is defined as mortality within 5 years of initiating HD) is shown in Table 5. Event rates for the case mix model are 3%, 10%, 22% and 42% for risk categories of 0–5%, 5–<15%, 15–30% and >30%, respectively. On the other hand, event rates for the case mix model with RDW are 2.5%, 10%, 16% and 44% for risk categories of 0–5%, 5–<15%, 15–30% and >30%, respectively. Hence, the case mix model with RDW seems to be a better model as it classified more people in the highest risk group.

Table 3.

The AUCusing ROC analysis to predict all cause mortality within first year of initiating hemodialysis using different laboratory variables in addition to case mix variables as listed.

| 1 year mortality | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Case Mix variables | 0.734 (0.730–0.739) | |

| Case Mix + RDW | 0.763 (0.758–0.767) | <0.001 |

| Case Mix+ Albumin | 0.758 (0.753–0.762) | <0.001 |

| Case Mix+ Hemoglobin | 0.734 (0.731–0.741) | <0.001 |

| Case Mix+ Ferritin | 0.734 (0.731–0.741) | <0.001 |

| Case Mix+ % Iron saturation | 0.734 (0.731–0.471) | <0.001 |

Note: Associations given as AUC (95% confidence interval). Case mix variables include: age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, African American, Hispanic, Asian and other), co-morbidities, primary insurance, dialysis access, cause of end stage renal disease, hospitalization history, and delivered dialysis dose. P-value represents likelihood ratio comparing case-mix models to case-mix+ laboratory variables

AUC, area under the curve; RDW, red cell distribution width; ROC, receiver operating characteristic

Table 4.

Test of discriminatory value to evaluate predictive value of RDW in comparison to other laboratory variables in hemodialysis patients who died within 1 year and 5 year study period.

| 1 year mortality (95% CI) | 5 year mortality (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| RDW | ||

| IDI | 1.8% (1.7%–1.9%) | 2.5% (2.4%–2.6%) |

| NRI* | 13.9% (13.0%–14.9%) | 13.6% (12.9%–14.2%) |

| Albumin | ||

| IDI | 2.7% (2.6%–2.8%) | 2.3% (2.2%–2.4%) |

| NRI* | 19.4% (18.3%–20.4%) | 15.5% (14.9%–16.1%) |

| Hemoglobin | ||

| IDI | 0.40% (0.35%–0.45%) | 0.03% (0.02%–0.04%) |

| NRI* | 4.5% (3.8%–5.2%) | 0.6% (0.4%–1.4%) |

| Ferritin | ||

| IDI | 0.31% (0.26%–0.37%) | 0.09% (0.07%–0.12%) |

| NRI* | 2.7% (2.2%–3.3%) | 1.6% (1.3%–1.8%) |

| % Iron Saturation | ||

| IDI | 0.12% (0.10%–0.15%) | 0.065% (0.063%–0.066%) |

| NRI* | 1.4% (0.9%–1.8%) | 1.2% (0.9%–1.4%) |

Note: Case mix variables include: age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, African American, Hispanic, Asian and other), co-morbidities, primary insurance, dialysis access, cause of end stage renal disease, hospitalization history, and delivered dialysis dose. NRI and IDI estimates compare case-mix adjusted models to case-mix plus laboratory variable.

CI, confidence interval; integrated discrimination improvement (IDI); net reclassification improvement (NRI); integrated discrimination improvement (IDI); RDW, red cell distribution width

Cut-off 5%, 15%, 30%.

Table 5.

Reclassification table for models with and without RDW as a predictor of event

| Case mix variables without RDW as predictor |

Case Mix variables with RDW as predictor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDW <5% | RDW 5–<15% | RDW 15–30% | RDW >30% | Total | Event rate |

|

| Event | ||||||

| RDW<5% | 31 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 49 | |

| RDW 5%–<15% | 37 | 1,625 | 612 | 49 | 2,323 | |

| RDW 15%–30% | 0 | 922 | 6,757 | 2,342 | 10,021 | |

| RDW >30% | 0 | 0 | 1,879 | 14,489 | 16,368 | |

| Total | 68 | 2,562 | 9,251 | 16,880 | 28,761 | |

| No Event | ||||||

| RDW <5% | 1,303 | 293 | 3 | 1 | 1,600 | |

| RDW 5%–<15% | 1,392 | 16,608 | 2,521 | 112 | 20,633 | |

| RDW 15%–30% | 0 | 6,670 | 24,313 | 3,982 | 34,965 | |

| RDW >30% | 0 | 2 | 5,210 | 17,497 | 22,709 | |

| Total | 2,695 | 23,573 | 32,047 | 21,592 | 79,907 | |

| All | ||||||

| RDW <5% | 1,334 | 308 | 6 | 1 | 1,649 | 3% |

| RDW 5%–<15% | 1,429 | 18,233 | 3,133 | 161 | 22,956 | 10% |

| RDW 15%–30% | 0 | 7,592 | 31,070 | 6,324 | 44,986 | 22% |

| RDW >30% | 0 | 2 | 7,089 | 31,986 | 39,077 | 42% |

| Total | 2,763 | 26,135 | 41,298 | 38,472 | 108,668 | |

| Event rate | 2.5% | 10% | 22% | 44% | ||

Note: Event is defined as mortality within 5 years of initiating hemodialysis.

RDW, red cell distribution width

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed a sensitivity analysis where we additionally adjusted for vitamin B12 and folate in addition to case mix plus MICS covariates in the time-varying analysis. Due to a large proportion of patients with missing data on vitamin B12 and folate (88% of patients), these two variables were not included in the main case mix plus MICS model. After restricting the sub-cohort to patients with an available vitamin B12 and folate measurement, the linear relationship between RDW and mortality persisted but was blunted, in particular for the MICS model additionally adjusted for vitamin B12 and folate. These results represent associations in a small subset of the analytical cohort and therefore may be subject to selection biases (Table S3).

Baseline characteristics of patients with complete data for all variables included in baseline case-mix and MICS adjusted models (n=99,303) were compared with those with complete data across all variables, including vitamin B12 and folate (n= 10,372). The two groups were similar except that there were a higher proportion of Caucasians and a lower proportion of Hispanics in the group with complete information. Dyslipidemia was also more prevalent in the group with complete information (Table S4).

In addition, we further evaluated the association of RDW with mortality after excluding patients with hemoglobin less than 12 g/dl in time-varying analysis. This was done to examine the effect of RDW on mortality prediction in non-anemic patients. The RDW remained significantly associated with all-cause mortality in this sub-cohort of patients (Table S5). In the case-mix plus MICS model, the lower time-varying RDW groups of <14.5% and 14.5%–<15.5% were associated with lower mortality risk (reference group: 15.5%–<16.5%: adjusted HRs of 0.75 [95% CI, 0.71–0. 79] and 0.88 [95% CI, 0.83–0.92]). On the other hand, the higher time-varying RDW groups of 16.5%–<17.5% and ≥17.5% were associated with higher mortality risk (adjusted HRs of 1.09 [95% CI, 1.02–1.15] and 1.26 [95% CI, 1.19–1.34], respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this contemporary cohort of 109,675 adult HD patients, we found a robust, consistent and linear relationship between RDW and mortality. As RDW increased, the risk of death also increased. This result remained consistent in patients with hemoglobin ≥ 12 g/dl. In addition, there was also an independent and additive effect of RDW in the assessment of survival in patients on maintenance HD. The AUC analyses demonstrated that RDW was a strong predictor of mortality, similar to albumin. Using reclassification analyses in the mortality prediction model, RDW improved the predictive value of the model by approximately 14% for 1-year and 5-year mortality. Based on our models, RDW might be a better predictor of mortality than hemoglobin, ferritin, and iron saturation. Furthermore, while previous studies across various non-CKD populations found significant correlations between RDW and hemoglobin concentration, CRP, ferritin, WBC, our study found no significant correlation between RDW, RBC indices, and various other laboratory/inflammatory markers suggesting that the pathogenesis of elevated RDW in patients on HD is probably more complex15.

It has been previously shown that kidney function is closely related to RDW. In 1989, Docci et al were the first to measure and compare RDW values in HD patients versus patients with normal eGFR; they concluded that RDW is higher in HD patients and tends to return to normal once HD patients are treated with iron14. In 2008, Lippi et al showed that in approximately 8500 patients with eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73m2 there is a strong graded decrease in eGFR with increase in RDW.17 A similar inverse relationship was found in another study in which both decreased eGFR and increased microalbuminuria were seen with higher levels of RDW18. In kidney transplant recipients, results have been similar1. More recently, a retrospective analysis has been performed in 296 patients that examined the role of RDW in HD patients without anemia. When these patients were grouped into four categories according to clinical parameters, albumin, and CRP, the group with both low serum albumin (<3.5 g/dl) and high CRP (>5 mg/L) had the highest RDW value. This suggests that even in non-anemic HD patients, RDW levels vary depending on the degree of malnutrition and inflammation19.

In addition to being closely linked to kidney function, increased RDW has also been associated with higher mortality. For the first time in 2007, it was identified as a prognostic marker for all-cause mortality in patients with congestive heart failure3. In more recent years, RDW has been associated with mortality and other adverse outcomes in various clinical conditions, including chronic and acute heart failure, acute dyspnea, acute pancreatitis, severe sepsis and septic shock, trauma, acute pulmonary embolism, older adulthood, and even acute kidney injury or kidney transplantation4–12. Similarly, results from a single center with 1293 incident PD patients demonstrated that patients with RDW ≥ 15.5% had an adjusted HR of 1.60 for cardiovascular mortality (RDW reference group: <15.5%)13. However, the impact of RDW on mortality in HD patients has not been well studied. To our knowledge, only one study in 100 HD patients from a single center has examined the RDW-mortality association. In that study, each 1% increase in RDW level was associated with a 54% higher all-cause mortality risk after one year in univariate Cox proportional hazard analyses15. The association between RDW and mortality reported in many diseases may reflect residual confounding from many conditions affecting RBC production and survival.

The exact mechanism by which RDW is linked to mortality is not clear. The RDW reflects heterogeneity in RBC size. Disorders causing increased RBC destruction and/or ineffective and increased RBC production, which are both prevalent in patients on dialysis, lead to an increase in RDW. Beyond functioning as a marker of ineffective erythropoiesis, there are other plausible mechanisms that might explain the RDW-mortality risk. First, inflammation inhibits bone marrow function and iron metabolism20 and pro-inflammatory cytokines have been determined to inhibit erythropoietin-induced erythrocyte maturation and proliferation and downregulate erythropoietin receptor expression, which is associated with increasing RDW21–23. Second, oxidative stress leads to increase in heterogeneity of RBC24,25. Despite having tremendous antioxidant capacity, red blood cells are prone to oxidative damage. Patients receiving HD have high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress due to multiple factors including blood contact with the dialysis membrane, microbial contamination of the dialysate, reduced levels of vitamins C and E, and reduced activity of the glutathione system. Third, malnutrition, which is common in HD patients, is known to increase RDW. Finally, the RDW has been shown to be an independent predictor of endothelial dysfunction26.

Our study is not without its limitations. First, as an observational study, it cannot prove a causal relationship between RDW and mortality. Second, we did not have comprehensive data that may be associated with both RDW and HD patient outcomes, such as blood transfusion data, socioeconomic status, and other known or unknown confounders. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. We also did not have information on cause of death and therefore could not examine cardiovascular mortality outcomes. Finally, the relevance of these findings is uncertain since it is not necessarily actionable. However, it is possible that similar to ferritin, RDW is a marker of inflammation and may help in recognizing patients with ESA resistance. Nevertheless, our study is remarkable for its nationally representative cohort, large sample size, and comprehensive data on labs and comorbidities.

In summary, we observed that higher RDW is strongly linked to higher mortality risk in HD patients. However, it is not clear as to whether higher RDW is a risk factor for mortality, or if it is an epiphenomenon of underlying biological and metabolic imbalances across RDW categories. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to infer that the assessment of this parameter should be broadened far beyond the differential diagnosis of anemia. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and to determine the mechanisms underlying the RDW-mortality association.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere appreciation to the DaVita clinics that ensure the extensive data collection on which this work is based.

Support: The study was supported by Dr Kalantar-Zadeh’s research grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health (K24-DK091419 and R01-DK078106), a research grant from DaVita Clinical Research, and philanthropic grants from Mr Harold Simmons and Mr Louis Chang.

Dr Kalantar-Zadeh was medical director of DaVita Harbor-UCLA Long Beach during 2007–2012.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The other authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: TV, ES, MZM, CMR, HM, CPK, KK-Z; data acquisition: TV, ES, KK-Z ; data analysis/interpretation: TV, ES, MZM, CMR, HM, MS, CPK, KK-Z; statistical analysis: TV, ES, MZM, MS, KK-Z; supervision or mentorship: KK-Z. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. KK-Z takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Peer Review: Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, a Statistical Editor, a Co-Editor, and the Editor-in-Chief.

Table S1: Association of baseline RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y.

Table S2: Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y.

Table S3: Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y in patients ever with vitamin B12 or folate measurement.

Table S4: Baseline characteristics of cohort with complete data for baseline case-mix and MICS covariates vs those with complete data across all variables.

Table S5: Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y in patients with hemoglobin ≥12 g/dL.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery

Supplementary Table S1 (PDF). Association of baseline RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y.

Supplementary Table S2 (PDF). Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y.

Supplementary Table S3 (PDF). Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y in patients ever with vitamin B12 or folate measurement.

Supplementary Table S4 (PDF). Baseline characteristics of cohort with complete data for baseline case-mix and MICS covariates vs those with complete data across all variables.

Supplementary Table S5 (PDF). Association of time-varying RDW with all-cause mortality over 5 y in patients with hemoglobin ≥12 g/dl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ujszaszi A, Molnar MZ, Czira ME, Novak M, Mucsi I. Renal function is independently associated with red cell distribution width in kidney transplant recipients: a potential new auxiliary parameter for the clinical evaluation of patients with chronic kidney disease. British journal of haematology. 2013;161(5):715–725. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karnad A, Poskitt TR. The automated complete blood cell count. Use of the red blood cell volume distribution width and mean platelet volume in evaluating anemia and thrombocytopenia. Archives of internal medicine. 1985;145(7):1270–1272. doi: 10.1001/archinte.145.7.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felker GM, Allen LA, Pocock SJ, et al. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong N, Oh J, Kang SM, et al. Red blood cell distribution width predicts early mortality in patients with acute dyspnea. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2012;413(11–12):992–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senol K, Saylam B, Kocaay F, Tez M. Red cell distribution width as a predictor of mortality in acute pancreatitis. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2013;31(4):687–689. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CH, Park JT, Kim EJ, et al. An increase in red blood cell distribution width from baseline predicts mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Critical care (London, England) 2013;17(6):R282. doi: 10.1186/cc13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadaka F, O'Brien J, Prakash S. Red cell distribution width and outcome in patients with septic shock. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2013;28(5):307–313. doi: 10.1177/0885066612452838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majercik S, Fox J, Knight S, Horne BD. Red cell distribution width is predictive of mortality in trauma patients. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2013;74(4):1021–1026. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182826f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen HS, Abakay O, Tanrikulu AC, et al. Is a complete blood cell count useful in determining the prognosis of pulmonary embolism? Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2014;126(11–12):347–354. doi: 10.1007/s00508-014-0537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel KV, Semba RD, Ferrucci L, et al. Red cell distribution width and mortality in older adults: a meta-analysis. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2010;65(3):258–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh HJ, Park JT, Kim JK, et al. Red blood cell distribution width is an independent predictor of mortality in acute kidney injury patients treated with continuous renal replacement therapy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27(2):589–594. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mucsi I, Ujszaszi A, Czira ME, Novak M, Molnar MZ. Red cell distribution width is associated with mortality in kidney transplant recipients. International urology and nephrology. 2014;46(3):641–651. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0530-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng F, Li Z, Zhong Z, et al. An increasing of red blood cell distribution width was associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients on peritoneal dialysis. International journal of cardiology. 2014;176(3):1379–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Docci D, Delvecchio C, Gollini C, Turci F, Baldrati L, Gilli P. Red blood cell volume distribution width (RDW) in uraemic patients on chronic haemodialysis. The International journal of artificial organs. 1989;12(3):170–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sicaja M, Pehar M, Derek L, et al. Red blood cell distribution width as a prognostic marker of mortality in patients on chronic dialysis: a single center, prospective longitudinal study. Croatian medical journal. 2013;54(1):25–32. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tefferi A, Hanson CA, Inwards DJ. How to interpret and pursue an abnormal complete blood cell count in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(7):923–936. doi: 10.4065/80.7.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lippi G, Targher G, Montagnana M, Salvagno GL, Zoppini G, Guidi GC. Relationship between red blood cell distribution width and kidney function tests in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Scandinavian journal of clinical and laboratory investigation. 2008;68(8):745–748. doi: 10.1080/00365510802213550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afonso L, Zalawadiya SK, Veeranna V, Panaich SS, Niraj A, Jacob S. Relationship between red cell distribution width and microalbuminuria: a population-based study of multiethnic representative US adults. Nephron. Clinical practice. 2011;119(4):c277–c282. doi: 10.1159/000328918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekce H, Kin Tekce B, Aktas G, Tanrisev M, Sit M. The evaluation of red cell distribution width in chronic hemodialysis patients. International journal of nephrology. 2014;2014:754370. doi: 10.1155/2014/754370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiari MM, Bagnoli R, De Luca PD, Monti M, Rampoldi E, Cunietti E. Influence of acute inflammation on iron and nutritional status indexes in older inpatients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(7):767–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jelkmann WE, Fandrey J, Frede S, Pagel H. Inhibition of erythropoietin production by cytokines. Implications for the anemia involved in inflammatory states. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1994;718:300–309. discussion 309–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faquin WC, Schneider TJ, Goldberg MA. Effect of inflammatory cytokines on hypoxia-induced erythropoietin production. Blood. 1992;79(8):1987–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdougall IC, Cooper AC. Erythropoietin resistance: the role of inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2002;17(Suppl 11):39–43. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_11.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbos KA, Claro LM, Borges L, Santos CA, Weffort-Santos AM. Human erythrocytes as a system for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of vegetable extracts. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.) 2008;28(7):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niki E, Komuro E, Takahashi M, Urano S, Ito E, Terao K. Oxidative hemolysis of erythrocytes and its inhibition by free radical scavengers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263(36):19809–19814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solak Y, Yilmaz MI, Saglam M, et al. Red cell distribution width is independently related to endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2014;347(2):118–124. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182996a96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.