Abstract

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) recently emerged as an important gaseous signaling molecule in plants. In this study, we investigated the possible functions of H2S in regulating Arabidopsis seed germination. NaHS treatments delayed seed germination in a dose-dependent manner and were ineffective in releasing seed dormancy. Interestingly, endogenous H2S content was enhanced in germinating seeds. This increase was correlated with higher activity of three enzymes (L-cysteine desulfhydrase, D-cysteine desulfhydrase, and β-cyanoalanine synthase) known as sources of H2S in plants. The H2S scavenger hypotaurine and the D/L cysteine desulfhydrase inhibitor propargylglycine significantly delayed seed germination. We analyzed the germinative capacity of des1 seeds mutated in Arabidopsis cytosolic L-cysteine desulfhydrase. Although the mutant seeds do not exhibit germination-evoked H2S formation, they retained similar germination capacity as the wild-type seeds. In addition, des1 seeds responded similarly to temperature and were as sensitive to ABA as wild type seeds. Taken together, these data suggest that, although its metabolism is stimulated upon seed imbibition, H2S plays, if any, a marginal role in regulating Arabidopsis seed germination under standard conditions.

Keywords: hydrogen sulfide, seed germination, seed dormancy, Arabidopsis, cysteine desulfhydrase

Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a toxic gas found in volcanic emissions or produced in waterlogged wetlands. It is also formed during human activities including agriculture and car use. Plants are therefore subjected to H2S exposure during their whole lifespan. Although acute exposure to H2S has long been known as deleterious for plants (Lisjak et al., 2013), numerous reports also indicate that low doses of H2S might be beneficial for plant fitness. For instance, exogenous treatments with H2S-releasing chemicals such as sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) improve the tolerance to abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, heavy metals, or high temperature in a variety of plant species (Jin et al., 2011; Christou et al., 2013, 2014; Shen et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2013). The mechanisms for H2S alleviation of abiotic stress effects unraveled so far are essentially the stimulation of antioxidant defense. For instance, the activities of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and ascorbate peroxidase are enhanced by NaHS treatments and contribute to maintain low levels of H2O2 (for review, Li, 2013). In addition, wheat plants water-stressed in the presence of NaHS display higher ascorbate and glutathione contents, as well as a higher proportion of reduced forms (Shan et al., 2011). Besides stimulating antioxidant defense, exogenous H2S treatments also trigger stomata movements which might participate in plant adaptive response to water and osmotic stress (García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010; Jin et al., 2013; Honda et al., 2015). Nevertheless, as opposite effects were observed i.e., the promotion of either stomata closure or opening (García-Mata and Lamattina, 2010; Lisjak et al., 2010), the outcome of such exogenous treatments might be conditioned by the overall plant physiological status.

Recent data raised further interest toward H2S in plants by highlighting a signaling function of endogenously produced H2S (for review, Lisjak et al., 2013). Three enzymes have been identified as sources of H2S in plants (Riemenschneider et al., 2005b; Alvarez et al., 2010; García et al., 2010). L- and D-cysteine desulfhydrases (L/D-CDes) produce H2S as a by-product of L/D-cysteine degradation. On the other hand, β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS) catalyzes the conversion of cysteine and cyanide to β-cyanoalanine and H2S. β-CAS activity is located in the mitochondria when desulfhydrases have been reported in mitochondria and cytosol (Romero et al., 2014). Of particular interest, Alvarez et al. (2010) characterized a cytosolic L-CDes designated DES1 that modulates the generation of H2S in the cytosol. The corresponding des1 mutants exhibit a reduced H2S content that is correlated with a premature leaf senescence and the overexpression of senescence associated genes (Álvarez et al., 2012a). Further, investigations also indicated that des1 mutants are more sensitive to drought, in good accordance with their impaired ABA-responsive stomatal closure (Jin et al., 2013). More globally, des1 mutants appear more sensitive to abiotic and biotic stresses and present a lower induction of stress-responsive genes (Shi et al., 2015). Altogether it is now obvious that data obtained by manipulating exogenous or endogenous H2S level converge and plead for an important role of this compound in the regulation of plant response under stress.

Whereas the involvement of H2S in plants under stress is well established, its function in plant development has been far less investigated. In that sense, seed germination represents an interesting study case. Indeed germination being the first step of plant life cycle is crucial for the establishment of a robust plantlet. Under natural conditions, it also determines the efficiency of wild species to proliferate in ecosystems. The ability to germinate is therefore tightly controlled to occur only when environmental conditions get favorable for the successful development of the plantlet. In most species, mature seeds are dormant i.e., are unable to germinate under favorable conditions, and germination capacity is acquired only after seed dormancy has been released. Seed dormancy release and germination are therefore the two integral faces of a same coin when considering freshly harvested seeds. Dormancy release is controlled by a complex set of environmental, e.g., temperature or light, and internal, e.g., hormones, signals (Shu et al., 2016). When successful, germination is completed within a short window that starts with seed imbibition and ends up with radicle protrusion.

Several studies have addressed the effect of H2S treatment on seed germination (Zhang et al., 2008, 2010a,b; Li et al., 2012; Dooley et al., 2013). Nevertheless, in most of the cases, only combined effects of H2S and stress (e.g., osmotic, oxidative, or metal stress) have been reported. When studied alone (Zhang et al., 2010a; Dooley et al., 2013), contrasting effects of H2S were observed. Zhang et al. (2010a) observed no differences of wheat germination in the absence or presence of up to 1.5 mM NaHS. On the other hand, Dooley et al. (2013) reported a stimulation of germination in the four species analyzed (i.e., wheat, corn, pea, and bean). Noteworthy, in most of the cases (species, NaHS concentration), NaHS treatment only accelerated germination but hardly modify final germination efficiency (Dooley et al., 2013). Although these data suggest that modifications of H2S availability during seed imbibition could affect seed germination, no information on a possible role for endogenously evoked H2S have been reported. In the present paper, we further investigated the metabolism and possible involvement of H2S in Arabidopsis seeds germinated under standard conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant material and germination assays

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds of Columbia-0 (Col-0) ecotype were used throughout the study. The des1-1 mutant (SALK_103855) presents a T-DNA insertion in the second exon of DES1 gene (At5g28030) leading to a knockout mutation (Alvarez et al., 2010). Col-0 and des1-1 seeds were propagated simultaneously as previously described (Basbouss-Serhal et al., 2015). Plants were grown in a climate chamber (20/22°C under long day photoperiod (16 h light/8 h dark)) on a soil/perlite (2:1) mixture. Floral stems were cut at silique maturity (about 3 months after sowing) and dried for 4 days at room temperature in paper envelopes before seeds were collected. Freshly harvested seeds were stored at –20°C to preserve their dormancy.

Seed germination was tested in 9-cm Petri dishes (50 seeds per dish, three replicates) on a filter paper on the top of a layer of cotton wool moistened with 20 mL of deionized water or indicated solutions. Plated seeds were subsequently kept in the dark in growth chambers at the required temperature. Germination was scored over time, a seed being considered as germinated when the radicle protruded through the testa. All the chemicals assayed during germination tests were directly dissolved in the deionized water used for seed imbibition.

Chemicals

D-cysteine (C8005), hypotaurine (H1384), and DL-propargylglycine (P7888) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (L'Isle d'Abeau Chesnes, France).

Enzyme activity measurements

Seed material (30 mg of dry seeds per condition before imbibition) consisting of dry seeds or seeds imbibed for 6, 16, or 24 h was collected by rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen. After grinding in liquid nitrogen, soluble proteins were extracted from seed powder by the addition of 1 mL of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) containing 2.5 mM DTT and 10 μL of protease inhibitor cocktail (P9599, Sigma-Aldrich, L'Isle d'Abeau Chesnes, France). Following centrifugation (14,000 g, 4°C, 45 min), protein content was determined and was adjusted to 1 mg.mL−1.

L-cysteine desulfhydrase (L-CDes) activity was assayed essentially as previously described (Riemenschneider et al., 2005a). Reactions were performed in 1 mL final volume of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9), 2.5 mM DTT, 0.8 mM L-cysteine, and 50 μg of soluble proteins. Following incubation at 37°C for 15 min, reactions were stopped by the addition of 100 μL of 20 mM N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (in 7.2 N HCl) and 100 μL of 30 mM FeCl3 (in 1.2 N HCl). After 10 min incubation at room temperature and centrifugation (14,000 g, 5 min), the formation of methylene blue was quantified at 670 nm. For the calculation of H2S formation, known quantities of NaHS were assayed in the same conditions, and used for standard curve determination.

D-cysteine desulfhydrase (D-CDes) was assayed in the conditions described for L-CDes activity except that Tris-HCl buffer was pH 8 and L-cysteine was replaced by D-Cysteine.

β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS) activity was assayed as described in Meyer et al. (2003). Reactions were performed in 1 mL final volume of 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9), 0.8 mM L-cysteine, 10 mM KCN and 100 μg of soluble proteins. Following incubation at 30°C for 15 min, reactions were stopped and subsequently processed as described above for L-CDes activity.

Hydrogen sulfide quantification

Seed endogenous hydrogen quantification was adapted from Christou et al. (2013). Dry or imbibed seeds (30 mg) were ground in liquid nitrogen and seed powder was resuspended in 500 μL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 10 mM EDTA. Following centrifugation (14,000 g, 4°C, 15 min), H2S content from 100 μL supernatant was measured in a final volume of 2 mL containing 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), 10 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid). After 5 min incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was determined at 412 nm. H2S quantity was deduced from a standard curve obtained with known NaHS concentrations.

Results

Exogenous NaHS treatments delay arabidopsis seed germination

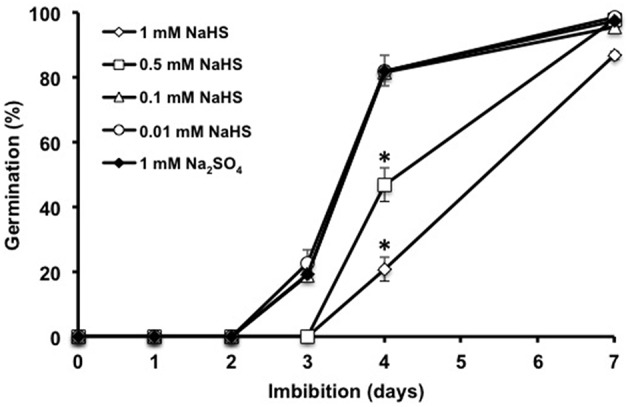

Recent data suggested that treating seeds with H2S-releasing chemicals such as sodium hydrosulfide (NaHS) might stimulate seed germination in different legume and cereal species (Dooley et al., 2013). Using freshly harvested Arabidopsis seeds, germination was compared in the absence or presence of various concentrations of NaHS. As shown on Figure 1, germination was not affected when up to 100 μM NaHS was applied, but was delayed by higher concentrations, in a dose-dependent manner. When imbibed at 25°C, seeds did not germinate whatever the concentration of NaHS was, indicating that seed dormancy cannot be alleviated by NaHS treatment (data not shown). These data suggest that exogenously applied H2S, when efficient, negatively impacts Arabidopsis germination.

Figure 1.

Effect of the H2S donor NaHS on Arabidopsis seed germination. Seeds (50 per condition) were imbibed on paper filters soaked with distilled water containing 1 mM Na2SO4 (control, close diamonds), 0.01 mM (open circles), 0.1 mM (open triangles), 0.5 mM (open squares), or 1 mM NaHS (open diamonds). Germination was recorded after incubation at 15°C in the dark for the indicated durations. Values are the mean ± S.E. of six experiments. Asterisks represent statistical differences relative to control at the same time point (Student's test; *P < 0.05).

Endogenous H2S level increases during seed imbibition

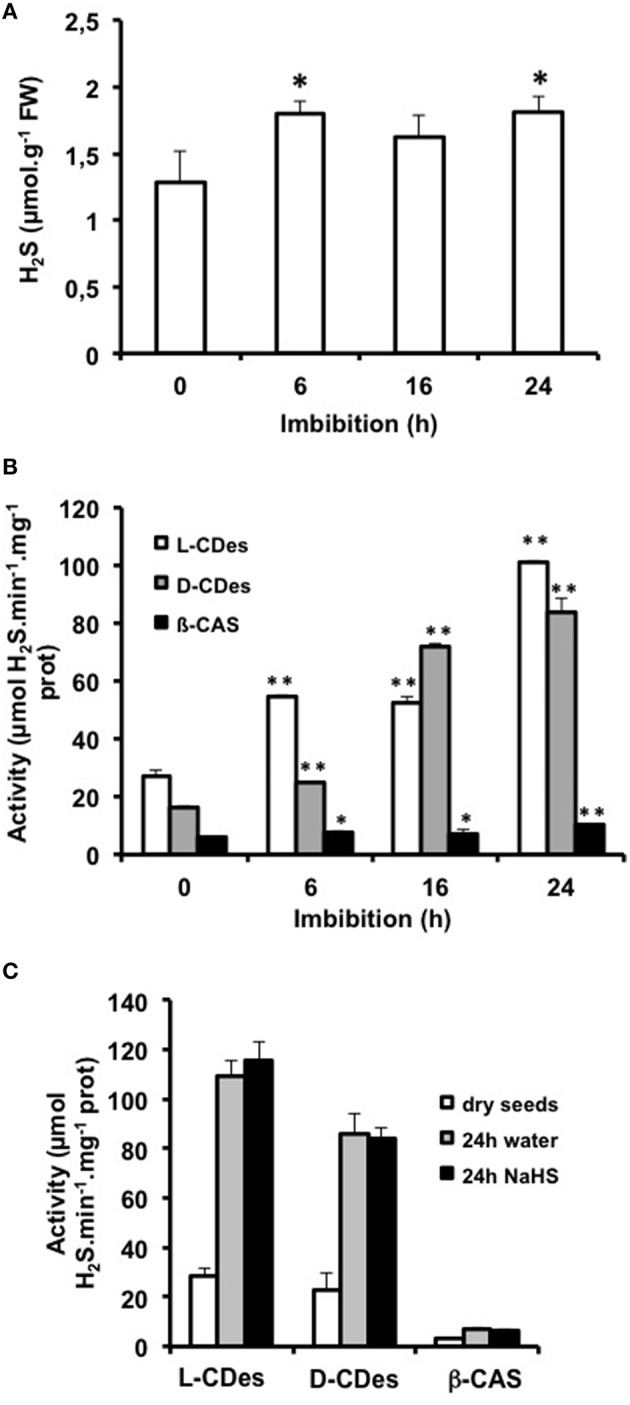

To get further information on the possible involvement of H2S in regulating germinative capacity, we assessed whether seeds processing to germination endogenously produced H2S during imbibition. As shown on Figure 2A, a slight increase (~40% compared to dry seeds) of H2S content was observed after 6 h imbibition and was maintained at 24 h. To evaluate the origin(s) of the H2S produced during seed imbibition, the activity of three enzymes reported to generate H2S in plants, i.e., L-cysteine desulfhydrase (L-CDes; E.C. 4.4.1.28), D-cysteine desulfhydrase (D-CDes; E.C. 4.4.1.15), and β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS; E.C. 4.4.1.9), was compared in dry and imbibed seeds (Figure 2B). The three activities could be detected in protein extracts from dry seeds. All three activities were stimulated in imbibed seeds and reached a maximum after 24 h At this time point, activity was 3.7, 5.25, and 1.7 fold higher than in dry seeds, for L-CDes, D-CDes, and β-CAS, respectively. Nevertheless, the level of β-CAS activity remained ~10 fold lower than that of CDes activities suggesting that L- and D-CDes were likely the major sources of H2S during seed germination. Based on these observations, we investigated the impact of seed treatments with NaHS on L-CDes, D-CDes, and β-CAS activities. As shown on Figure 2C, the activities of the three enzymes were similar for seeds imbibed 24 h in the absence or presence of NaHS suggesting that the delay of seed germination triggered by high NaHS concentrations is not achieved via the modification of endogenous H2S metabolism.

Figure 2.

H2S synthesis during Arabidopsis seed imbibition. (A) Evolution of Arabidopsis seed H2S content during imbibition. Seeds were imbibed on distilled water in the dark at 15°C. Values are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Asterisks represent statistical differences relative to H2S content in dry seeds (Student's test; *P < 0.05); (B) Evolution of the activities of H2S-generating enzymes in imbibed Arabidopsis seeds. Seeds were imbibed on distilled water in the dark at 15°C for the indicated durations. Total proteins were subsequently extracted and used for the measurement of L-cysteine desulfhydrase (L-CDes, white bars), D-cysteine desulfhydrase (D-CDes, gray bars), and β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS, dark bars) activities. Values are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Asterisks represent statistical differences relative to the activity in dry seed protein extracts (Student's test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01); (C) Evolution of the activities of H2S-generating enzymes in Arabidopsis seeds imbibed on water or 1 mM NaHS. Seeds were imbibed on distilled water or 1 mM NaHS in the dark at 15°C for 24 h. Total proteins were subsequently extracted and used for the measurement of L-cysteine desulfhydrase (L-CDes), D-cysteine desulfhydrase (D-CDes), and β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS) activities. Activities were compared with those of dry seeds. Values are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

Impairment of H2S accumulation during imbibition delays seed germination

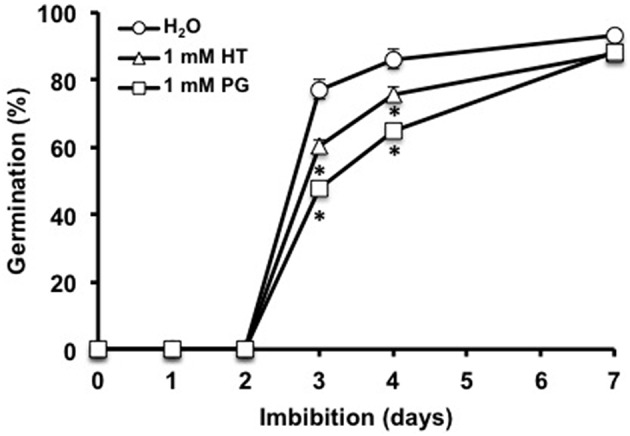

To assess whether endogenous H2S might participate in regulating germination, seeds were germinated in the presence of hypotaurine (HT, a H2S scavenger) or DL-propargylglycine (PG, an inhibitor of CDes). After 3 days, germination was reduced by 25 and 40% by HT and PG, respectively (Figure 3). Nevertheless, HT and PG did not block, but only delayed germination, as comparable final rates of germination were reached after 7 days. These data indicate that impairing endogenous H2S formation impacts seed germination capacity.

Figure 3.

Effect of inhibitors of H2S synthesis on Arabidopsis seed germination. Seeds (50 per condition) were imbibed on paper filters soaked with distilled water (control, circles), 1 mM hypotaurine (HT, triangles) or 1 mM propargylglycine (PG, squares). Germination was recorded after incubation at 15°C in the dark for the indicated durations. Values are the mean ± S.E. of six experiments. Asterisks represent statistical differences relative to control at the same time point (Student's test; *P < 0.05).

D-Cdes mutant seeds do not accumulate H2S during imbibition but exhibit unmodified germination

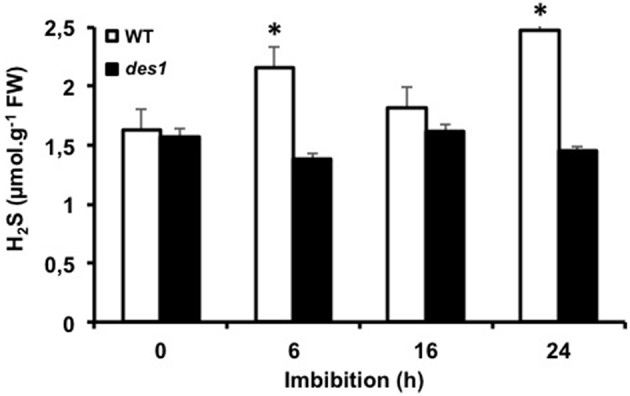

The impairment of germination by PG treatment together with the strong increase of CDes activities during seed imbibition suggested the involvement of CDes in H2S generation in imbibed seeds. A mutant line for DES1 gene (des1-1) deficient for the sole cytosolic L-CDes characterized to date (Alvarez et al., 2010) was therefore analyzed for H2S production in imbibed seeds. The H2S content of freshly harvested des1 seeds was compared with that of WT seeds at the dry state or after different durations of imbibition at 15°C (Figure 4). Comparable H2S contents were measured in WT and des1 dry seeds. In contrast, whereas H2S content raised in WT seeds after imbibition, it remained unmodified over 24 h of imbibition in des1 seeds, therefore implicating DES1 as a major source for H2S in germinating Arabidopsis seeds.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the endogenous H2S content of wild-type and des1 seeds during imbibition. Wild-type (white bars) and des1 (dark bars) seeds were imbibed on distilled water in the dark at 15°C. Values are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Asterisks represent statistical differences relative to H2S content in dry seeds (Student's test; *P < 0.05).

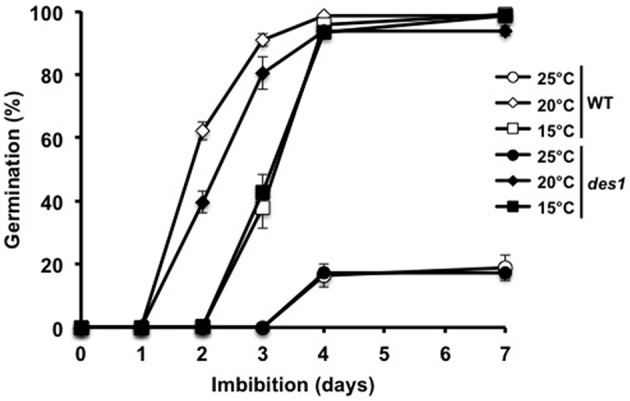

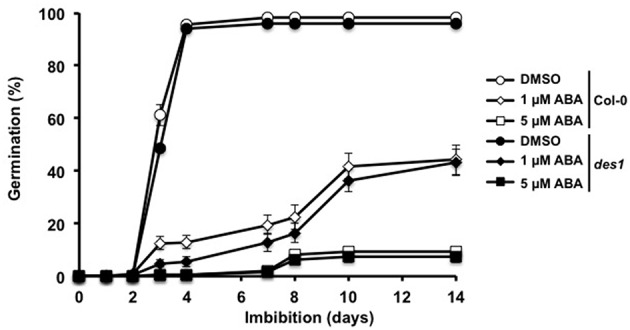

We further compared WT and des1 mutant seeds under conditions known to influence germinative capacity. We first monitored the effect of temperature on the germination of both lines (Figure 5). When imbibed at 25°C, freshly harvested WT and des1 seeds presented a low (~20%) percentage of germination, indicating that both seed lines were essentially dormant. At 15°C, the same lines fully germinated after 4 days. Imbibition at 20°C also led to full germination, with no significant difference between WT and des1 seeds. These data therefore indicate that the mutation of DES1 gene does not modify seed behavior when germinated at different temperatures nor than the dormancy of freshly harvested seeds. In addition, des1 seeds presented a comparable sensitivity to NaHS treatments (Figure S1), which further suggests that the delay of germination triggered by NaHS is independent of endogenous H2S metabolism. As H2S has recently been evidenced as an intermediate of ABA signaling in leaf stomata, we compared the sensitivity of WT and des1 seed germination to ABA. To achieve full and homogeneous germination of the two lines in the absence of ABA, the assays were run at 15°C. As shown on Figure 6, the germination of WT and des1 seeds was sensitive to ABA. Indeed, the germination rate of WT and des1 seeds was reduced by 60 and 90% in the presence of 1 and 5 μM ABA respectively. Therefore, the mutation of DES1 gene does not modify the sensitivity of seed germination to ABA.

Figure 5.

Effect of temperature on wild-type and des1 seed germination. Wild-type (open symbols) and des1 (closed symbols) seeds were imbibed on distilled water and germinated in the dark at 15°C (squares), 20°C (diamonds), or 25°C (circles). Values are mean ± S.E. of six experiments.

Figure 6.

Effect of ABA on wild-type and des1 seed germination. Wild-type (open symbols) and des1 (closed symbols) seeds were imbibed on distilled water containing 1% DMSO (circles), 1 μM ABA (diamonds) or 5 μM ABA (squares). Seeds were subsequently incubated at 15°C in the dark. Values are mean ± S.E. of six experiments.

Discussion

Recent years have provided an array of studies evidencing the biological effects of H2S in plants (Lisjak et al., 2013; Jin and Pei, 2015). Among them several reports suggested that H2S stimulated seed germination (Zhang et al., 2008, 2010a,b; Li et al., 2012; Dooley et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the observations essentially evidenced the capacity of H2S to alleviate the negative effects of stresses on germination, but were poorly informative on the effect of H2S on germination per se. Using Arabidopsis seeds as a model, we investigated the involvement of H2S in regulating germination under standard conditions. As reported in several physiological contexts including plant response to auxin (Fang et al., 2014), salt, and osmotic stress (Christou et al., 2013) or hypoxia (Cheng et al., 2013), we observed a significant increase of H2S content in seeds during imbibition. This increase occurred after 6 h and was maintained over 24 h. Increased production of H2S had been observed previously in seeds submitted to Al and osmotic stress (Zhang et al., 2010a,b). Our data indicate that it also occurs under standard germination conditions in the absence of stressing factors. It therefore suggested that endogenously evoked H2S might function as a signal during germination.

Different sources for H2S production have been reported in plants (Romero et al., 2014). In relation with seed physiology, Xie et al. (2014) correlated the variations of H2S content in wheat aleurone layers with the activity of L-cysteine desulfhydrase (L-CDes), the major source of H2S in plants (Alvarez et al., 2010). We could measure a L-CDes activity (27 ± 2 nmol H2S.min−1.mg prot−1) in dry Arabidopsis seeds in the range of those reported for plant tissues (10–150 nmol H2S.min−1.mg prot−1) (Riemenschneider et al., 2005a; Alvarez et al., 2010; Hou et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2014). L-CDes activity was strongly enhanced during imbibition, reaching a maximum after 24 h. It could therefore afford for the higher H2S contents found in imbibed seeds. We also observed a concomitant increase of the activity of D-cysteine desulfhydrase (D-CDes) and β-cyanoalanine synthase (β-CAS), two other enzymes generating H2S in plants (Riemenschneider et al., 2005a; García et al., 2010). Because of the toxicity of H2S for cytochrome c oxidase, it is unlikely that H2S generated by the mitochondrial β-CAS could accumulate to significant levels in planta, and the higher β-CAS activity is therefore likely related to cyanide detoxification (Álvarez et al., 2012b). D-CDes that exhibits a strong activity in imbibed seeds could generate part of the H2S measured in seeds, assuming that D-cysteine levels are sufficient (Riemenschneider et al., 2005b). Nevertheless, our study indicates that L-CDes is critical for H2S production in imbibed seeds. Indeed, knock-out mutant seeds for the DES1 gene that encodes the cytosolic L-CDes (Alvarez et al., 2010) presented similar H2S contents in dry and imbibed seeds. The stimulation of DES1 activity is therefore the main route for the enhanced H2S production observed in imbibed seeds. On the other hand, the basal H2S level found in dry seeds and detected in imbibed des1 mutant seeds might be related to β-CAS and/or D-CDes activities. It might also be due to unidentified L-CDes enzymes as suggested by the significant L-CDes activity retained by the des1 mutant (Alvarez et al., 2010).

To decipher the requirement and possible function of H2S during seed germination, we used chemicals either artificially releasing H2S (NaHS) or inhibiting endogenous H2S formation (hypotaurine and propargylglycine). No effect of NaHS was observed at low concentrations (≤100 μM), whereas germination was significantly delayed at higher concentrations. This effect is likely due to a massive and rapid release of H2S from NaHS toxic for the plant material. Indeed no such retardation was observed with GYY4137, that releases lower H2S doses (Lisjak et al., 2010), and GYY4137 did not affect Arabidopsis seed germination at any concentrations tested up to 1 mM (data not shown). Our data further illustrate contrasted effects of H2S on seed germination observed under standard conditions. Indeed, no effect was found on wheat seed germination in the presence of up to 1.5 mM NaHS (Zhang et al., 2010a). On the other hand, Dooley et al. (2013) reported a stimulation of seed germination by H2S in diverse plant species including corn, pea, bean, and wheat. Different sensitivities toward stimulators/inhibitors of germination are frequently observed between species and might afford for the different response to H2S treatment in different species (Finch-Savage and Leubner-Metzger, 2006). In addition the response might depend on the conditions used for treatment and germination (light status, temperature…) that are varying between studies.

To get further insights in the function of endogenously evoked H2S, we used hypotaurine and propargylglycine to modulate H2S content in seeds. Hypotaurine (HT) is a potent H2S scavenger (Ortega et al., 2008) and has been used in plants to lower intracellular H2S content (Li et al., 2014). Propargylglycine (PG) inhibits CDes activities (Steegborn et al., 1999) and blocks H2S production in plants (Li et al., 2014). When applied during seed imbibition both compounds strongly delayed germination. As their modes of action are different this effect is certainly reached through the blocking of H2S formation. It therefore supports that endogenous H2S formation is required for optimal germination. Noteworthy the effect of HT and PG was similar to that of high NaHS treatments, which questioned on the possible impact of NaHS application on seed H2S metabolism. Although the mechanisms by which high NaHS concentrations delay germination are unknown, our data indicate that they do not rely on modifications of endogenous H2S metabolism. Indeed seeds imbibed in the presence or absence of NaHS exhibit similar L-CDes, D-CDes, and β-CAS activities. Moreover, the germination of des1 seeds was as sensitive as WT seeds to NaHS. These observations are consistent with previous data by Riemenschneider et al. (2005a) indicating that L-CDes and D-CDes activities were not affected in H2S-fumigated Arabidopsis plants. On the other hand optimal germination might require a particular level of endogenous H2S that would be unbalanced by exogenous NaHS, HT, and PG treatments. This phenomenon has been proposed for H2O2 for which too low or too high intracellular levels both lead to germination impairment (Bailly et al., 2008). In any case, only a delay of germination, and not a full inhibition, has been observed for the different treatments. As long-term effects of HT and PG have been reported with lower concentrations than the one used in our study (Li et al., 2014), it is unlikely that HT and PG loose their efficiency over time. It more likely reflects that endogenously evoked H2S, although fastening germination, is not a requisite. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that des1 mutant seeds germinate at similar rates compared to WT seeds. Experiments run at 15°C indicate that DES1 activity, and more generally endogenously evoked H2S, is dispensable for germination. Similarly, because both des1 and WT seeds hardly germinate at 25°C, DES1-dependent H2S production is not required for seed dormancy. In good accordance with this, des1 and WT seeds exhibited comparable sensitivity toward ABA, which is the major regulator of seed dormancy. Contrarily to stomata that exhibit an altered response to ABA in des1 mutant and in which DES1-dependent H2S formation is an intermediate of ABA signaling (Scuffi et al., 2014), our data indicate that ABA signaling in seeds is independent of DES1. More globally, as no altered development has been observed for des1 seedlings (Alvarez et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2013), our data further highlight that DES1 is dispensable during the early stages of plant development under optimal growth conditions.

Taken together our data highlight that although H2S is produced at the early stages of seed imbibition essentially via the activity of L-CDes, its importance, if any, for germination under standard conditions is limited in Arabidopsis. This contrasts with other reactive species such as hydrogen peroxide or nitric oxide that are now considered as major regulators of seed germination and seed dormancy release (Arc et al., 2013; Diaz-Vivancos et al., 2013). As treatments with H2S donors efficiently alleviate inhibition of germination by abiotic stresses, future works should be focused on deciphering whether endogenously evoked H2S participates in abiotic stress tolerance during seed germination and could therefore constitute a trait for variety selection and improvement.

Author contributions

EB, JP, and CB designed the research. EB, AP, NI, and FC carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. EB, JP, and CB contributed to writing the manuscript. EB and CB supervised the project.

Funding

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Université Pierre et Marie Curie- Paris 6.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Gotor (Institute of Plant Biochemistry and Photosynthesis, Sevilla, Spain) for providing des1 mutant seeds. We are grateful to Dr. J. Hancock (UWE, Bristol, UK) for fruitful discussions.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00930

Effect of NaHS treatments on wild-type and des1 seed germination. WT and des1 seeds (50 per condition) were imbibed on paper filters soaked with distilled water containing 1 mM Na2SO4 (0) or increasing concentrations of NaHS. Germination was recorded after incubation at 15°C in the dark for 4 days. For all the conditions, 98–100% germination was achieved after 7 days. Values are the mean ± S.E. of three experiments.

References

- Alvarez C., Calo L., Romero L. C., García I., Gotor C. (2010). An O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase homolog with L-cysteine desulfhydrase activity regulates cysteine homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 152, 656–669. 10.1104/pp.109.147975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez C., García I., Moreno I., Pérez-Pérez M. E., Crespo J. L., Romero L. C., et al. (2012a). Cysteine-generated sulfide in the cytosol negatively regulates autophagy and modulates the transcriptional profile in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 4621–4634. 10.1105/tpc.112.105403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez C., García I., Romero L. C., Gotor C. (2012b). Mitochondrial sulfide detoxification requires a functional isoform O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase C in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 5, 1217–1226. 10.1093/mp/sss043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arc E., Galland M., Godin B., Cueff G., Rajjou L. (2013). Nitric oxide implication in the control of seed dormancy and germination. Front. Plant Sci. 4:346. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailly C., El-Maarouf-Bouteau H., Corbineau F. (2008). From intracellular signaling networks to cell death: the dual role of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. C. R. Biol. 331, 806–814. 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbouss-Serhal I., Soubigou-Taconnat L., Bailly C., Leymarie J. (2015). Germination potential of dormant and nondormant Arabidopsis seeds is driven by distinct recruitment of messenger RNAs to polysomes. Plant Physiol. 168, 1049–1065. 10.1104/pp.15.00510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W., Zhang L., Jiao C., Su M., Yang T., Zhou L., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates hypoxia-induced root tip death in Pisum sativum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 70, 278–286. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou A., Filippou P., Manganaris G. A., Fotopoulos V. (2014). Sodium hydrosulfide induces systemic thermotolerance to strawberry plants through transcriptional regulation of heat shock proteins and aquaporin. BMC Plant Biol. 14:42. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christou A., Manganaris G. A., Papadopoulos I., Fotopoulos V. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide induces systemic tolerance to salinity and non-ionic osmotic stress in strawberry plants through modification of reactive species biosynthesis and transcriptional regulation of multiple defence pathways. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 1953–1966. 10.1093/jxb/ert055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Vivancos P., Barba-Espín G., Hernández J. A. (2013). Elucidating hormonal/ROS networks during seed germination: insights and perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 32, 1491–1502. 10.1007/s00299-013-1473-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley F. D., Nair S. P., Ward P. D. (2013). Increased growth and germination success in plants following hydrogen sulfide administration. PLoS ONE 8:e62048. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T., Cao Z., Li J., Shen W., Huang L. (2014). Auxin-induced hydrogen sulfide generation is involved in lateral root formation in tomato. Plant Physiol. 76, 44–51. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch-Savage W. E., Leubner-Metzger G. (2006). Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytol. 171, 501–523. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García I., Castellano J. M., Vioque B., Solano R., Gotor C., Romero L. C. (2010). Mitochondrial beta-cyanoalanine synthase is essential for root hair formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22, 3268–3279. 10.1105/tpc.110.076828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mata C., Lamattina L. (2010). Hydrogen sulphide, a novel gasotransmitter involved in guard cell signalling. New Phytol. 188, 977–984. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K., Yamada N., Yoshida R., Ihara H., Sawa T., Akaike T., et al. (2015). 8-Mercapto-Cyclic GMP Mediates Hydrogen sulfide-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 1481–1489. 10.1093/pcp/pcv069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z., Wang L., Liu J., Hou L., Liu X. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide regulates ethylene-induced stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 55, 277–289. 10.1111/jipb.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Pei Y. (2015). Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide in plants: pleasant exploration behind Its unpleasant odour. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015:397502. 10.1155/2015/397502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Shen J., Qiao Z., Yang G., Wang R., Pei Y. (2011). Hydrogen sulfide improves drought resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414, 481–486. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Xue S., Luo Y., Tian B., Fang H., Li H., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide interacting with abscisic acid in stomatal regulation responses to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 62, 41–46. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-J., Chen J., Xian M., Zhou L.-G., Han F. X., Gan L.-J., et al. (2014). In site bioimaging of hydrogen sulfide uncovers its pivotal role in regulating nitric oxide-induced lateral root formation. PLoS ONE 9:e90340. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. G. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide: A multifunctional gaseous molecule in plants. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 60, 733–740. 10.1134/S1021443713060058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.-G., Gong M., Liu P. (2012). Hydrogen sulfide is a mediator in H2O2-induced seed germination in Jatropha Curcas. Acta Physiol. Plant. 34, 2207–2213. 10.1007/s11738-012-1021-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lisjak M., Srivastava N., Teklic T., Civale L., Lewandowski K., Wilson I., et al. (2010). A novel hydrogen sulfide donor causes stomatal opening and reduces nitric oxide accumulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 931–935. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisjak M., Teklic T., Wilson I. D., Whiteman M., Hancock J. T. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide: environmental factor or signalling molecule? Plant Cell Environ. 36, 1607–1616. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T., Burow M., Bauer M., Papenbrock J. (2003). Arabidopsis sulfurtransferases: investigation of their function during senescence and in cyanide detoxification. Planta 217, 1–10. 10.1007/s00425-002-0964-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega J. A., Ortega J. M., Julian D. (2008). Hypotaurine and sulfhydryl-containing antioxidants reduce H2S toxicity in erythrocytes from a marine invertebrate. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3816–3825. 10.1242/jeb.021303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemenschneider A., Nikiforova V., Hoefgen R., De Kok L. J., Papenbrock J. (2005a). Impact of elevated H2S on metabolite levels, activity of enzymes and expression of genes involved in cysteine metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43, 473–483. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemenschneider A., Wegele R., Schmidt A., Papenbrock J. (2005b). Isolation and characterization of a D-cysteine desulfhydrase protein from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J. 272, 1291–1304. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L. C., Aroca M. Á., Laureano-Marín A. M., Moreno I., García I., Gotor C. (2014). Cysteine and cysteine-related signaling pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 7, 264–276. 10.1093/mp/sst168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuffi D., Álvarez C., Laspina N., Gotor C., Lamattina L., García-Mata C. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide generated by L-cysteine desulfhydrase acts upstream of nitric oxide to modulate abscisic acid-dependent stomatal closure. Plant Physiol. 166, 2065–2076. 10.1104/pp.114.245373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan C., Zhang S., Li D., Zhao Y., Tian X., Zhao X., et al. (2011). Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on the ascorbate and glutathione metabolism in wheat seedlings leaves under water stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 33, 2533–2540. 10.1007/s11738-011-0746-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Xing T., Yuan H., Liu Z., Jin Z., Zhang L., et al. (2013). Hydrogen sulfide improves drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana by microRNA expressions. PLoS ONE 8:e77047. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Ye T., Chan Z. (2013). Exogenous application of hydrogen sulfide donor sodium hydrosulfide enhanced multiple abiotic stress tolerance in bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 71, 226–234. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Ye T., Han N., Bian H., Liu X., Chan Z. (2015). Hydrogen sulfide regulates abiotic stress tolerance and biotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 57, 628–640. 10.1111/jipb.12302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu K., Liu X.-D., Xie Q., He Z.-H. (2016). Two faces of one seed: hormonal regulation of dormancy and germination. Mol. Plant 9, 34–45. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegborn C., Clausen T., Sondermann P., Jacob U., Worbs M., Marinkovic S., et al. (1999). Kinetics and inhibition of recombinant human cystathionine gamma-lyase. Toward the rational control of transsulfuration. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12675–12684. 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Zhang C., Lai D., Sun Y., Samma M. K., Zhang J., et al. (2014). Hydrogen sulfide delays GA-triggered programmed cell death in wheat aleurone layers by the modulation of glutathione homeostasis and heme oxygenase-1 expression. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 53–62. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Hu L.-Y., Hu K.-D., He Y.-D., Wang S.-H., Luo J.-P. (2008). Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination and alleviates oxidative damage against copper stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50, 1518–1529. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Tan Z.-Q., Hu L.-Y., Wang S.-H., Luo J.-P., Jones R. L. (2010a). Hydrogen sulfide alleviates aluminum toxicity in germinating wheat seedlings. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 556–567. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00946.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Wang M. J., Hu L. Y., Wang S. H., Hu K. D., Bao L. J., et al. (2010b). Hydrogen sulfide promotes wheat seed germination under osmotic stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 57, 532–539. 10.1134/S1021443710040114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of NaHS treatments on wild-type and des1 seed germination. WT and des1 seeds (50 per condition) were imbibed on paper filters soaked with distilled water containing 1 mM Na2SO4 (0) or increasing concentrations of NaHS. Germination was recorded after incubation at 15°C in the dark for 4 days. For all the conditions, 98–100% germination was achieved after 7 days. Values are the mean ± S.E. of three experiments.