Abstract

Background

Labour pain can be deleterious for mother and baby. Epidural analgesia relieves labour pains effectively with minimal maternal and foetal side effects. A prospective open label study was undertaken to ascertain effective dosing regime for walking epidural in labour.

Methods

Fifty women with singleton foetus in vertex position were included. Epidural catheter was inserted in L2-3 / L3-4 interspinous space. Initial bolus of 10 ml (0.1% bupivacaine and 0.0002% fentanyl) solution was injected and after the efficacy of block was established, an epidural infusion of the same drug solution was started at the rate of 5 ml/hour.

Results

In first stage of labour 80% of the parturient had excellent to good pain relief (visual analogue scale 1 to 3) with standard protocol while 20% parturient required one or more additional boluses. For the second stage, pain relief was good to fair (VAS 4-6) for most of the parturient. The incidence of caesarian section was 4% and 6% needed assisted delivery. No major side effects were observed.

Conclusion

0.1% bupivacaine with 0.0002% fentanyl maximizes labour pain relief and minimizes side effects.

Key Words: Labour analgesia, Walking epidural

Introduction

Labour and delivery results in severe pain for many women. The McGill Pain Questionnaire ranks labour pain in the upper part of the pain scale between cancer pain and amputation of a digit [1]. The goal of maternal labour analgesia is relief of pain without compromising maternal safety, progress of labour and foetal well-being. Epidural analgesia is the most effective and least depressant method of intrapartum pain relief in current practice [2]. Low concentration of bupivacaine combined with fentanyl, results in analgesia with minimal side effects [3]. The aim of the study, was to develop a safe dosing regime to provide satisfactory pain relief with minimal side effects.

Material and Methods

It was a prospective open label study. We studied 45 primiparous and five second gravida women with singleton foetus in vertex position admitted for parturition in the age group of 18-30 years. Parturients with obstetric complications like pre-eclampsia, preterm labour, previous caesarian, abnormal lie and placenta previa were excluded from the study. Once the parturient is in active phase of labour i.e. cervix is 3-4 cms dilated, anaesthesiologist was called for lumbar epidural block.

After explaining the procedure, 500 ml of ringer lactate was infused as preload. Pre-epidural pulse, blood pressure (BP), SpO2 and pain score (using Visual Analogue Scale-VAS) were checked. Foetal heart rate (FHR) was continuously monitored using cardiotocograph. All the parturient were kept fasting, but clear fluids were allowed till delivery. Epidural space was identified in L2-3 / L3-4 interspinous space using loss of resistance to saline and multiorifice epidural catheter inserted. Initial bolus of 10 ml of drug solution (0.1% bupivacaine and 0.0002% fentanyl) was injected in two aliquots, five ml in left lateral and five ml in right lateral position at an interval of five minutes. Maternal pulse, BP, SpO2 and FHR were monitored every five minutes for the first 30 minutes. After 30 minutes pain score using VAS and motor blockade using modified Bromage Score (Table 1) was checked. If pain relief was satisfactory (VAS <5) and there were no motor block or evidence of significant hypotension an epidural infusion (with syringe infusion pump) of the same drug solution was started at the rate of 5ml /hour. Patient was assessed at 30 minutes interval for pain relief (objective assessment using VAS on 1-10 scale and subjective assessment by mother as excellent/good/fair/poor), maternal haemodynamics, foetal heart rate, motor block, duration of second stage of labour, incidence of caesarian section, instrumental delivery, side effects, complications (sedation, nausea, vomiting, itching, urinary retention) and total dose of bupivacaine and fentanyl used.

Table 1.

Modified Bromage Score

| Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ability to raise extended legs |

| 2 | Inability to raise extended legs and decreased knee flexion, but full extension of feet and ankles present |

| 3 | Inability to raise legs or flex knees, but flexion of ankles present |

| 4 | Inability to raise legs, flex knees or ankles or move toes |

Obstetrician monitored labour by repeated internal examination (two hourly) and feeling uterine contractions. During first stage, sitting in bed or walking was allowed. When VAS was more than 5, a bolus of five ml of drug solution was given through infusion pump. At full cervical dilatation parturients were allowed to walk to second stage delivery room. For second stage, parturients lied in lithotomy position with head up. In primigravidae local infiltration of 2 ml of 2% lignocaine was given before episiotomy. After delivery, epidural catheter was removed and duration of second stage noted. Neonatal Apgar at one and five minutes were recorded. Parturients were interviewed a day after delivery for satisfaction level, backache and willingness for labour epidural for subsequent pregnancy. Results were statistically analyzed using Student's t-test.

Results

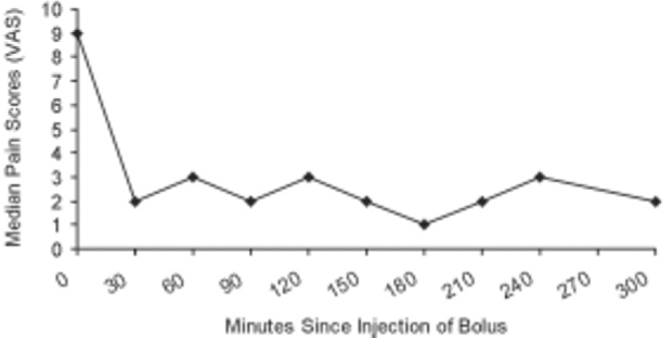

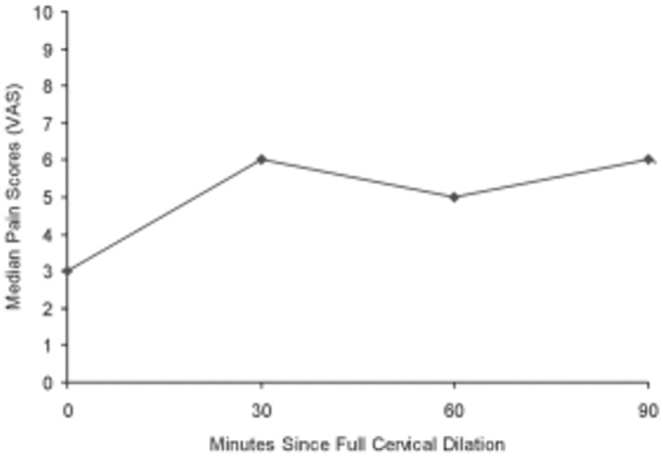

At the time of inserting epidural catheter all parturients experienced severe labour pains (VAS 8-10). After initial 10 ml bolus the mean maternal blood pressure and pulse did not vary by more than 10% of pre-epidural values. Oxygen saturation was 98-99% in all the parturients. After 30 minutes of bolus, mean VAS was 1-3 and parturient own assessment was excellent to good pain relief. For the first stage, pain relief was excellent to good and median pain scores were 1-3 for 80 % of parturients (Fig. 1). Ten parturients required additional bolus of five ml after 2-3 hours. For the second stage, pain relief was good to fair with median pain scores 4-6 for all the parturients (Fig. 2). None had motor weakness (Bromage Score 1-2), loss of sensations in lower half of body or sedation. All parturients were able to walk to second stage room for the delivery. The duration of second stage was 30-90 minutes. There was no incidence of itching or urinary retention. Forty five parturients were able to bear down effectively and delivered vaginally without assistance. The decrease in pain scores during first stage of labour was found to be highly significant. However the motor block and change in hemodynamic parameters were not significant.

Fig 1.

Median pain scores (VAS) during first stage of labour

Fig 2.

Median pain scores (VAS) during second stage of labour

Two parturients required caesarian section because of cervical dystocia. For caesarian section 15-20 ml bupivacaine 0.5% was injected through epidural catheter and catheter was left for 48 hours for postoperative pain relief. Three parturients required vacuum assisted delivery. In all cases neonatal Apgar at one minute was 7-8 and at five minutes 8-9. There was no incidence of neonatal depression. The total dose of bupivacaine varied from 15 to 40 mg and fentanyl from 30 to 80 μg depending upon duration of labour. When interviewed next day, all patients were satisfied with pain relief and none complained of backache. All were willing for labour epidural for subsequent pregnancy.

Discussion

Higher concentration of bupivacaine was used as an intermittent bolus in the past, which resulted in fairly high incidence of motor block and instrumental deliveries. For labour epidurals several dosing regimens exist, but we devised our own protocol using 0.1% bupivacaine with 0.0002% fentanyl as bolus, followed by continuous infusion at the rate of 5ml /hour. A continuous infusion of a dilute mixture offers the advantage of a stable level of analgesia, increased maternal hemodynamic stability, lowered risk of systemic local anaesthetic toxicity and a slower ascent of the level of anaesthesia should intravascular or subarachnoid migration of catheter occur. Some studies suggest that the continuous technique results in the administration of greater total dose but not greater maternal or umbilical venous drug concentration [4].

‘Loss of resistance to saline’ technique to identify epidural space, results in decreased incidence of patchy block. Many workers recommend test dose before giving epidural bolus, to confirm catheter placement [5] but this lacks sensitivity and specificity [6]. We have not given any test dose. In our study 80% parturient had excellent to good pain relief (median VAS 1-3) within 15-30 minutes of bolus. After about 2-3 hours of bolus, 10 parturient had increased pain (VAS 5-6) and were given five ml bolus through the infusion pump. This bolus brought down the VAS to 2-3. Pain relief for second stage was not satisfactory for most. Second stage pain results from foetal descent and distension of vagina and perineum. Second stage pain relief requires higher concentration of bupivacaine which could result in motor weakness. All parturients could feel the uterine contractions and psychological satisfaction of participating in the process of labour. Due to analgesic efficacy of fentanyl, the dose of bupivacaine was reduced thereby decreasing the maternal and foetal toxicity [7]. There was no incidence of hypotension, desaturation, motor or sensory block. The incidence of caesarian section (4%) and instrument assisted deliveries (6%) were much lower in our study. This is probably due to the selection of parturients having favorable cervix who could deliver vaginally for this study.

Several retrospective studies have demonstrated an association between epidural analgesia and increased duration of first and second stage of labour, oxytocin augmentation, instrumental vaginal delivery and caesarian section for dystocia. In these studies, the probability of caesarian section for dystocia increased three-to-six times [8]. However, several recent prospective studies have concluded that epidural analgesia does not adversely affect progress of labour or increase the rate of caesarian section [9]. Ambulation during labour increases maternal comfort and intensity of uterine contractions, avoids inferior vena caval compression, facilitates foetal head descent and relaxes the pelvic musculature, all of which shorten labour. However, the preponderance of evidence suggests that ambulation during labour is not associated with these benefits [10]. The Apgar score of 8-9 at five minutes, is comparable to the study by Chestnut et al [11]. While using intrathecal opioid for labour analgesia Cutbush et al [12] observed shortened duration of labour. We cannot comment on duration of first stage in our study. The second stage of labour was not prolonged indicating that bupivacaine in concentration of 0.1% does not interfere with the bearing down efforts of mother. The study by Chestnut et al [13] states that combination of bupivacaine and fentanyl does not prolong second stage. The combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique, whereby selected advantages of each technique are combined, has gained increasing popularity in recent years [14, 15].

In conclusion, 0.1% bupivacaine with 0.0002% fentanyl bolus followed by continuous epidural infusion, provided a faster onset of analgesia with a long lasting effect. The parturient remains ambulant and pain free. The dose of bupivacaine was reduced due to addition of fentanyl, thereby reducing maternal or foetal toxicity. The concentrations of bupivacaine and fentanyl do not prolong labour or increase the incidence of caesarian section.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified

References

- 1.Melzack R, Taenzer P, Feldmen P, Kinch RA. Labour is still painful after prepared childbirth training. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;125:357–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson JO, Rosen M, Evans JM. Maternal opinion about analgesia for labour. A controlled trial between epidural block and intramuscular pethidine combined with inhalation. Anaesthesia. 1980;35:1173–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1980.tb05074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Writer D. Epidural Analgesia for labour. Anaesthesiology Clinics of North America. 1992;10:59–85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smedstad KG, Morison DH. A comparative study of continuous and intermittent epidural analgesia for labour. Can J Anesth. 1988;35:234–241. doi: 10.1007/BF03010616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbach DJ, Chestnut DH. The epidural test dose in obstetric practice: Has it outlived its usefulness? Anesth Analg. 1999;88:971–973. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris MC, Ferrenbach D, Dalman H. Does epinephrine improve the diagnostic accuracy of aspiration during labour epidural analgesia? Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1073–1076. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernando R, Borello E, Gill P. Neonatal welfare and placental transfer of fentanyl and bupivacaine during ambulatory combined spinal-epidural analgesia for labour. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.154-az0160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman E, Lang JM, Cohen A, D'Agostino R, Jr, Datta S, Frigoletto FD. Association of epidural analgesia with caesarian delivery in nulliparas. Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;88:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bofill JA, Vincent RD, Ross EL, Martin RW, Norman PF, Werhan CF. Nulliparous active labour, epidural analgesia, and caesarian delivery for dystocia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1565–1570. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallejo MC, Firestone LL, Mandell GL, Jaime F, Makishima S, Ramanathan S. Effect of epidural analgesia with ambulation on labour duration. Anaesthesiology. 2002;95:857–861. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200110000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chestnut DS, Owen Cindy. Continuous infusion epidural analgesia during labour. A randomized double blind comparison of 0.0625% bupivacaine / 0.0002% fentanyl versus 0.125% bupivacaine. Anaesthesiology. 1988;68:749–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutbush CM, McDonough JP, Clark K, McCarthy EJ. CRNA. 1998;9:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chestnut DH, Laszewski Linda J. Continuous epidural infusion of 0.0625% bupivacaine and 0.0002% fentanyl during the second stage of labour. Anaesthesiology. 1990;72:613–618. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199004000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heppner C, Gaiser R, Cheek TG, Gutsche BB. Comparison of combined spinal epidural and low dose epidural for labour analgesia. Canadian J of Anaesth. 2000;47:232–236. doi: 10.1007/BF03018918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collies RE, Davis DW, Aveling W. Randomised comparison of spinal-epidural and standard epidural analgesia in labour. Lancet. 1995;345:1413–1416. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]