Abstract

Tissue-engineered blood vessels (TEVs) are typically produced using the pulsatile, uniaxial circumferential stretch to mechanically condition and strengthen the arterial grafts. Despite improvements in the mechanical integrity of TEVs after uniaxial conditioning, these tissues fail to achieve critical properties of native arteries such as matrix content, collagen fiber orientation, and mechanical strength. As a result, uniaxially loaded TEVs can result in mechanical failure, thrombus, or stenosis on implantation. In planar tissue equivalents such as artificial skin, biaxial loading has been shown to improve matrix production and mechanical properties. To date however, multiaxial loading has not been examined as a means to improve mechanical and biochemical properties of TEVs during culture. Therefore, we developed a novel bioreactor that utilizes both circumferential and axial stretch that more closely simulates loading conditions in native arteries, and we examined the suture strength, matrix production, fiber orientation, and cell proliferation. After 3 months of biaxial loading, TEVs developed a formation of mature elastic fibers that consisted of elastin cores and microfibril sheaths. Furthermore, the distinctive features of collagen undulation and crimp in the biaxial TEVs were absent in both uniaxial and static TEVs. Relative to the uniaxially loaded TEVs, tissues that underwent biaxial loading remodeled and realigned collagen fibers toward a more physiologic, native-like organization. The biaxial TEVs also showed increased mechanical strength (suture retention load of 303 ± 14.53 g, with a wall thickness of 0.76 ± 0.028 mm) and increased compliance. The increase in compliance was due to combinatorial effects of mature elastic fibers, undulated collagen fibers, and collagen matrix orientation. In conclusion, biaxial stretching is a potential means to regenerate TEVs with improved matrix production, collagen organization, and mechanical properties.

Significance Statement

This work demonstrates the advantages of a novel bioreactor design for improving the biomechanical properties of engineered arteries. Native arteries experience cyclic multiaxial stresses due to pulsatile blood flow (circumferential) and axial prestretch along the tubular geometry of the vessel. However, most previous tissue engineering approaches have focused on imposing only the uniaxial loads during culture. This work imposes native-like loading conditions (circumferential and axial stretch) onto engineered vascular grafts. To model axial tension that develops in vivo during somatic growth, we simulated the combined effects of cyclic circumferential and axial stresses by subjecting the tissue-engineered vessels to biaxial loads during culture. The biaxially loaded constructs developed elastic fibers and a collagen structure that more closely resembled native tissue, resulting in an increase in compliance as well as in suture retention strength. Hence, in contrast to conventional uniaxial loading, biaxial loading results in tissue-engineered vessels that better mimic native arteries in biological function and mechanical performance.

Introduction

Tissue engineering of blood vessel substitutes has recently emerged as a means to treat patients with cardiovascular disease.1–8 Current tissue engineering methods readily produce blood vessel equivalents that generally resemble native arteries; however, these approaches sometimes fail to generate vessels exhibiting biochemical and mechanical properties that are required for long-term use in arterial circulation. A deficiency in tissue strength could result in graft failure via rupture, whereas graft/artery compliance mismatch may cause disturbances in blood flow and result in failure via thrombosis or intimal hyperplasia.9,10

To address the mechanical shortcomings of artificial engineered vessels, several groups have utilized the cyclic uniaxial (circumferential) stretch to generate mechanically robust tissue-engineered blood vessels (TEVs).1,11–13 However, tissues cultured in uniaxially stretched systems also undergo preferred alignment of collagen fibers in the direction of stretch. This preferred alignment results in a tissue that is mechanically robust in the circumferential (preferred) loading condition, but that may be weak under loading in the transverse direction.14–16 Collagen alignment may be advantageous in tissues that are uniaxially loaded such as ligaments, whereas native arteries are subjected to complex cyclic biaxial stresses and have complex collagen arrangements.17–19

Arteries, including the ascending aorta and coronary arteries, experience axial loading in addition to circumferential loading.20,21 The circumferential stress is attributed to the beat-to-beat pressure loading that is superimposed on distension via diastolic pressure, whereas the axial distension arises from somatic growth.22,23 In the native arteries, there are three orientations of collagen arrangement that withstand multi-axial loads: circumferential (0–10° relative to the cross-section of the vessel), helical (15–60°), and 65–90° (axial–helical).17–19 The orientation of collagen changes progressively from the intima to the adventitia. For example, the collagen fibers in the adventitia layer are more axial in orientation. Conversely, collagen fibers in the tunica media are primarily aligned in the circumferential direction.24 This layer-specific collagen structure is shown to play an active role in the mechanical properties of each section of the vessel, and also in overall vascular mechanics.24 As luminal pressure increases, the helical (anisotropic) collagen fibers become more circumferentially oriented (in the direction of applied stress), to reinforce mechanical properties at high stresses.24–26

The lack of multi-axial loading conditions in conventional vascular bioreactors may explain some of the fundamental differences in functionality between native and engineered arteries. Our basic hypothesis is that axial loading is a pivotal regulator of arterial morphogenesis and homeostasis, as well as an important variable in the development of engineered blood vessels. Currently, there exist in vitro stretch systems that are capable of imparting biaxial loading onto three dimensional tubular constructs, but these systems were designed solely for mechanical characterization of tissues rather than for long-term culture of TEVs.27,28

We built a novel system that is capable of long-term cyclic biaxial loading during the culture of TEVs ex vivo. To investigate the effects of cyclic biaxial stretching on TEVs on extracellular matrix (ECM) composition and organization as well as on biaxial mechanical properties, we compared polyglycolic acid (PGA)-based TEVs subjected to static, cyclic uniaxial, or cyclic biaxial culture for 12 to 13 weeks. Our findings show that biaxial loading enhances the formation of mature elastic fibers, which, in turn, positively impact collagen fiber organization. Specifically, biaxial loading promoted the development of residual stresses within the TEV wall and increased overall vascular compliance while preserving tissue strength and cell viability.

Materials and Methods

Biaxial bioreactor setup and culture

As previously described, bioreactors were set up for static, uniaxial (pulsatile circumferential stretching), or biaxial (combined pulsatile circumferential and slow cyclic axial stretching) cultures.4 TEVs were cultured in triplicate per experiment (Fig. 1). Briefly, 7 × 106 bovine smooth muscle cells (SMCs) at passage 2 were seeded onto 3-mm diameter × 4-cm-long tubular PGA scaffolds. Each PGA scaffold (n = 3 per experimental condition) was then placed over a distensible silicone tube to enable pressurization. Seeded SMCs were allowed to attach to the scaffolds for 30 min before adding growth medium to the bioreactors, which were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The growth medium consisted of high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin G (100 U/mL; Sigma), ascorbic acid (50 ng/mL; Sigma), CuSO4 (3 ng/mL; Sigma), 5 mM HEPES, proline (50 ng/mL, Sigma), glycine (50 ng/mL, Sigma), and alanine (20 ng/mL, Sigma). Culture medium was refreshed weekly, and fresh ascorbic acid was supplemented every 2 days. All TEVs were harvested between 12 and 13 weeks after cell seeding.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of biaxial bioreactor system. (A) A schematic top view of the biaxial bioreactor. Three biaxial vessels can be cultured and axially stretched in parallel. Flow passes from one end to the other end of the bioreactor. (B) Gross image of TEVs inside the bioreactor on harvest. (C) A schematic of the biaxial bioreactor connected to both the flow system and a linear motor to generate cyclic biaxial stretch. TEVs, tissue engineered blood vessels.

Application of mechanical stretching

The uniaxial pulsatile bioreactor was maintained at 270 mmHg/-30 mmHg at 245 bpm, whereas the static bioreactor was maintained unperturbed (no circumferential or axial stretching, Fig. 1A).29 The biaxial bioreactor was attached to a linear shaft motor stage (SCR075) at the axially movable connectors (Fig. 1C), which allowed the TEVs to be stretched axially up to 8% at 0.0333 Hz, based on previous work.30 The same pulsatile pressures (270 mmHg/−30 mmHg, 245 bpm) were applied to the biaxial and uniaxial bioreactors by connecting the bioreactors to the flow system (Fig. 1C). The luminal pressure of 270 mmHg resulted in a 1.5% to 2% circumferential strain on the silicone tubing, based on previous work.29

Transmission electron microscopy

TEVs were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 30 min and then at 4°C for 30 min. The samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h and stained en bloc in 2% uranyl acetate in maleate buffer (pH 5.2) for 1 h. The sections were then collected on nickel grids and stained using 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were viewed on an FEI Tencai Biotwin transmission electron microscope at 80 kV. Images were taken using a Morada CCD digital camera using iTEM (Olympus) software.

Collagen quantification

Collagen content was determined by measuring the level of hydroxyproline as previously described.31 Collagen content was calculated as 10 times the amount of hydroxyproline32 and normalized to mass per dry weight of tissue sample.

Desmosine assay

To establish the amount of mature elastin in each TEV, tissue samples with a wet weight of ∼3 mg were hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 110°C for 24 h. Subsequently, the samples were lyophilized and re-dissolved in water to measure the total protein mass for each TEV.33 The amount of desmosine was measured using the radioimmunoassay as previously described.34 Desmosine content was expressed as picomoles of desmosine per milligram protein in tissue samples.

Mechanical tests

Suture retention strength was measured by hanging weights at 2–3 mm from the edge (axial direction) of TEVs until tearing. TEVs were sectioned into ∼1.0 mm rings to assess opening angles, which reflect the presence of residual stress imparted by the presence of functional elastin fibers (passive) and cell tractional force (active). The rings were fastened to hollow bore needles with sutures and suspended in a normal saline solution to minimize effects of surface tension. Photomicrographs were taken both before and 30 min after cutting the rings. ImageJ software was used to determine wall thickness and opening angle.

Biaxial mechanical tests were performed on TEVs as previously described.35 Before removal from the bioreactors, India ink was used to mark the initial bioreactor length (in situ) of the TEVs (Fig. 4.1B). Subsequently, the unloaded length (final length) was measured and used to calculate the stretch ratio, λ, defined as the ratio between in situ and unloaded lengths. The TEVs were then secured to custom glass cannulae and then placed within Hanks phosphate-buffered solution (1.26 mM CaCl2 at 37°C) in a custom mechanical testing system.36 The luminal pressure, outer diameter (in the central region), axial force, and axial extension were all measured using protocols previously established.37,38 Briefly, all TEVs were subjected to four cycles of preconditioning, followed by three cycles of pressure–diameter tests (0–140 mmHg) at axial stretch ratios of 1.10, 1.16, and 1.21. Stretch ratios below in situ values were used to keep the force below the force transducer's maximum detection threshold of 980 mN. After mechanical testing, TEVs were exposed to intraluminal porcine pancreatic elastase at 7.5 U/mL (Worthington) for 10 min under the initial loading conditions. The residual elastase was then used to soak the outer surface of the TEVs for 5 min, and biaxial mechanical tests were repeated by following the same procedure previously discussed.37,38 Rings were cut from elastase-treated TEVs, and opening angles were also measured.

Optical clearing and second harmonic generation microscopy

TEVs were fixed in 4% PFA and optically cleared using a modification of a previously described method.39,40 Specimens were dehydrated via a graded series of ethanol (50%, 75%, 95%, 100%, 100%) at room temperature with each step lasting 10 min. Dehydrated TEVs were cleared using a 1:2 benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate (BABB) solution (volume by volume). After rinsing with 100% ethanol, TEVs were placed in a 1:1 solution of ethanol:BABB for at least 30 min, followed by a 100% BABB solution. Images were then captured using a custom multiphoton microscope that was previously described.39,40 The multiphoton microscope was equipped with a 5× Nikon objective lens with a 0.5 numerical aperture (AZ Plan Fluor; Nikon Corp.). The excitation source was an 80 MHz uniaxial Ti:Sapphire laser (Mai Tai, Spectra-Physics). An excitation wavelength of 740 nm with an ∼100 fs pulse width was used. Images were taken along the long axis of TEVs. Image z-stacks were collected and processed using SCANIMAGE software.

Analysis of ECM composition in biaxial TEVs

Cross-sections of TEVs stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Verhoeff-Van Gieson (VVG) were examined at both 5× and 40× magnification. A minimum of 50 cell nuclei were counted manually in each H&E image using ImageJ, and cell density was determined by normalizing cell number (nuclei) per mm2 tissue. Immunofluorescence staining was performed for SMC markers, elastic fibers, and collagen matrix. Briefly, sections were stained with 1:50 rabbit anti-elastin (ab21610; Abcam), anti-β-actin (A1978; Sigma), 1:150 rabbit anti-collagen III (ab7778; Abcam), 1:50 mouse anti-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 11 (SMMHC 11) (ab18147; Abcam), 1:5 for mouse anti-smoothelin (SC R4A; Santa Cruz), 1:10 mouse anti-fibrillin 1 (ab68444; Abcam), or 1:100 rabbit anti-fibronectin (ab23750; Abcam).

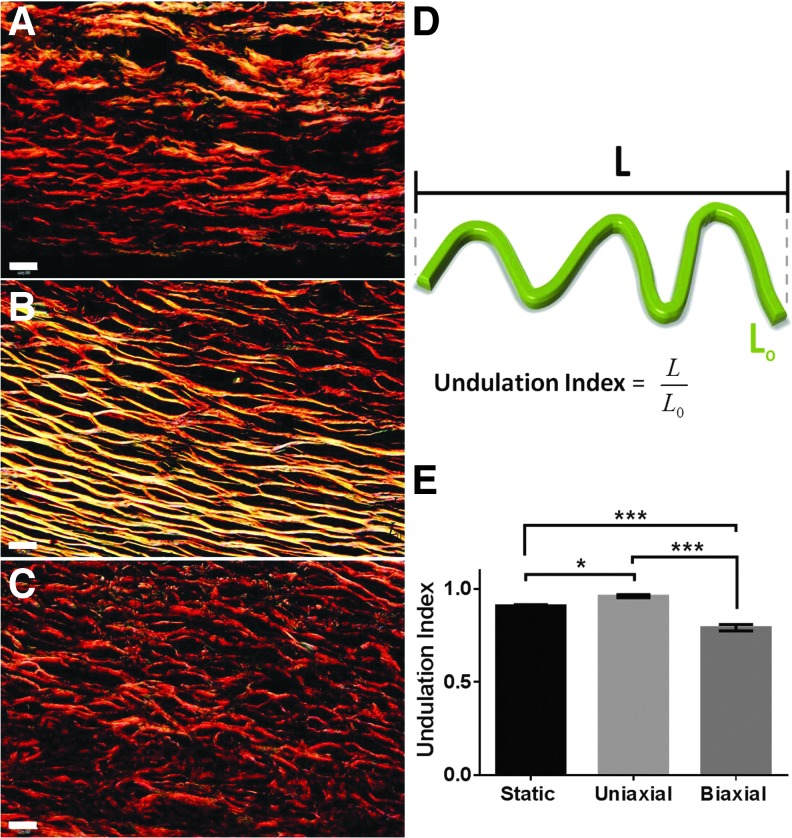

Collagen structure analysis: fibril diameter and fiber undulation

Collagen fibril diameter was measured manually in TEM images using ImageJ (300–350 fibrils were counted for each TEV). Picrosirius red stain was used to examine birefringence of fibrillar collagen in TEVs. Images of TEV cross-sections were acquired with an Olympus BX51TF microscope that was equipped with an Olympus DP70 camera using Olympus CellSens Dimension 1.4.1 software. Images were acquired using polarizing optics with dark-field imaging at 60×. Lengths of collagen fibers in dark field were measured using ImageJ. For each fiber, two length measurements were taken: shortest path length (L) and actual length of the fibers (L0) (Fig. 5D). An undulation index was defined as the ratio of the shortest path length to the actual length of the fiber (L/L0).41 The index ranged from 0 to 1, where “1” indicates no undulation and “0” refers to infinite undulation. In total, between 150 and 200 fibers were counted for each TEV.

FIG. 5.

Undulation of collagen fibers in biaxial TEVs under birefringence. (A) Static TEVs, (B) uniaxial TEVs, and (C) biaxial TEVs. (D) Schematic diagram describing the Undulation Index of collagen fibers, L/Lo. (E) Bar graph comparing Undulation Index of all three TEV groups. Scale bar: 20 μm (A–C). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

Collagen organization analysis: fiber angular dispersion

TEVs were divided evenly into three layers to reflect those of arterial walls (Supplementary Fig. S7A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec). Second harmonic generation (SHG) images (Supplementary Fig. S8) were converted into gray-scale images using ImageJ. Angular dispersion of collagen fibers in each SHG image was measured with Continuity software (UCSD, Cardiac Mechanics Research Group). The orientation of collagen fibers ranged from 0° to 90°, where 0° represents the circumferential collagen and 90° represents the axial collagen (Supplementary Fig. S7B). For each stratum, collagen fibers were assigned to one of the three groups: 0–10° (circumferential), 15–60° (physiological), and 65–90° (axial–helical) (Supplementary Fig. S7C), as previously described.24,25

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data (e.g., cell density, desmosine quantification, collagen quantification, angular dispersion, suture retention, collagen fibril diameter, undulation index, axial stretch ratio, wall thickness, and unloaded thickness) are expressed as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism 6 was used for statistical analysis with significance evaluated by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A paired student's t-test was used to compare opening angle both before and after elastase treatment. Tukey's multiple-comparisons test was used to examine the significance. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

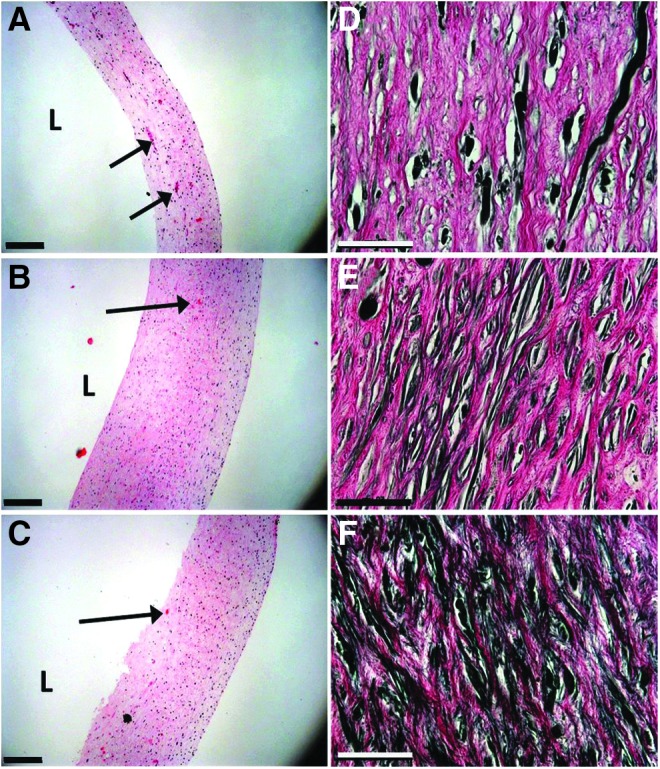

Wall properties of biaxial TEVs

Bioreactors were used to apply static conditions, cyclic uniaixal loading, or cyclic biaxial loading to TEVs ex vivo (Fig. 1). At the end of this period, all TEVs had a gross appearance similar to native arteries (Fig. 1B). In H&E staining, TEVs showed dense layers of intramural cells despite PGA fragments remaining near the lumen (Fig. 2A–C). Uniaxial (circumferentially stretched) and biaxial (circumferentially and axially stretched) TEVs developed similar wall thicknesses of 0.70 ± 0.038 mm (n = 3) and 0.76 ± 0.028 mm (n = 5), respectively, which were twofold greater than those observed in the static TEVs (0.300 ± 0.004 mm, n = 3, p < 0.05) (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Wall thicknesses of the uniaxial and biaxial TEVs are comparable to those of human coronary arteries (0.75 ± 0.17 mm).42

FIG. 2.

Histological images of engineered vessels. (A–C) H&E staining of TEV cross-sections. (D–F) VVG stain for elastin. Static vessels (A, D); uniaxial vessels (B, E); biaxial vessels (C, F). Scale bars: 200 μm for H&E and 50 μm VVG images. Arrows point to residual PGA segments. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PGA, polyglycolic acid; VVG, Verhoeff-Van Gieson.

Cell density in the static, uniaxial, and biaxial TEVs was 895 ± 35 nuclei/mm2 (n = 3), 1256 ± 43 nuclei/mm2 (n = 3), and 970 ± 135 nuclei/mm2 (n = 3), respectively. No statistical differences were found among these TEVs, even though the uniaxial TEVs showed the highest density of cells. Greater wall thicknesses in the uniaxial and biaxial TEVs also imply more cells in those TEVs as compared with the static TEVs.

Late SMC contractile markers were immunostained to evaluate differentiation under different mechanical conditions. All TEVs retained strong SMMHC expression, suggesting that static conditioning was sufficient to sustain highly differentiated SMCs in the culture medium used (Supplementary Fig. S2A–C). To further assess effects of mechanical cues on SMC differentiation, we examined smoothelin, a contractile maker expressed exclusively by fully differentiated SMCs.43 Unlike SMMHC, smoothelin was essentially absent in the static TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S2D), but present in both the uniaxial and biaxial TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S2E, F).

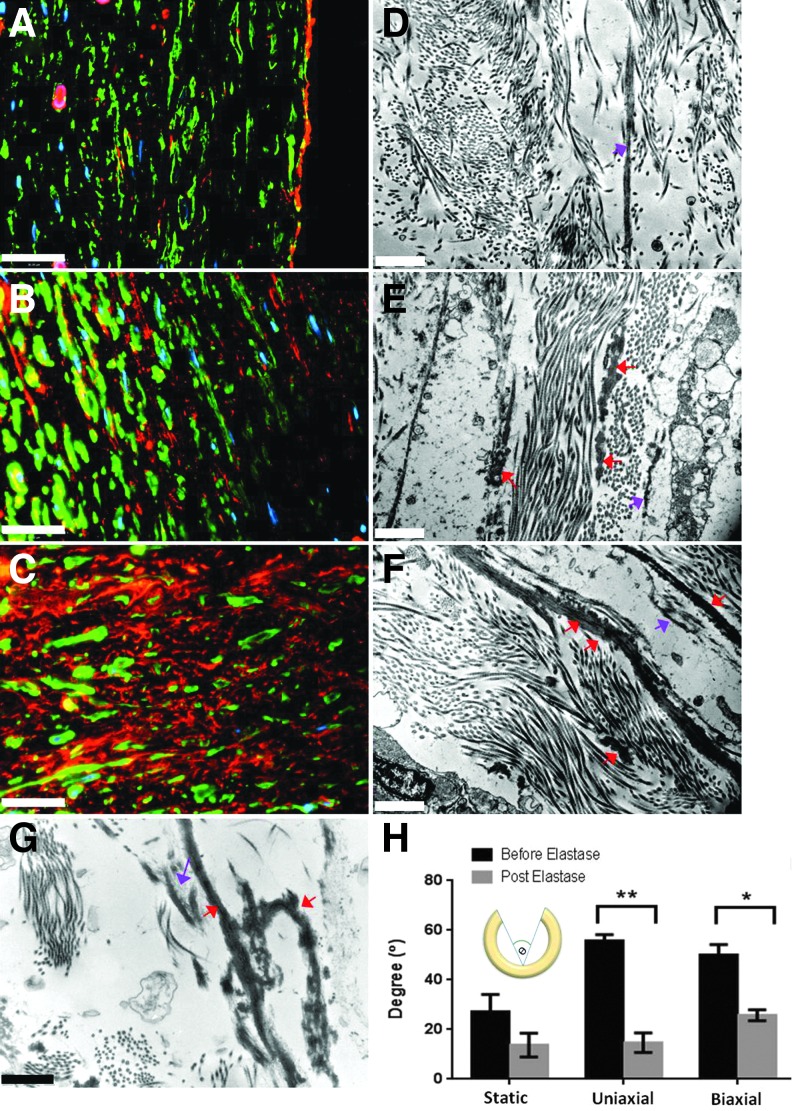

Biaxial stretching increases the formation of mature elastic fibers

VVG staining was used to visualize elastic fibers formed within the extracellular space (Fig. 2D–F). Cyclic biaxial loading enhanced elastic fiber formation as compared with static conditioning and uniaxial loading. Immunofluorescence staining was performed to identify extracellular elastin by double staining for an intracellular marker, β-actin. The biaxial TEVs developed significantly more extracellular elastin than either the static or uniaxial TEVs (Fig. 3A–C). Furthermore, the existence of desmosine (an elastin covalent cross-link) confirmed the presence of mature elastin in the biaxial and other TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The uniaxial TEVs showed a significantly higher desmosine content (325 ± 9 pmol/mg) than either biaxial (241 ± 19 pmole/mg, p < 0.05) or static (88 ± 13 pmol/mg, p < 0.001) TEVs. It is unclear as to why the uniaxially stretched tissues had higher desmosine levels, but it is likely, in part, due to the method of normalization. Given that the elastin levels are normalized on a per-protein basis, the enhanced production of other proteins (e.g., collagens) in biaxially stretched tissues could result in an artificially decreased/increased level of elastin.

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of extracellular elastic fiber maturity and elastin functionality via elastase treatment. (A, D) Static vessels; (B, E) uniaxial vessels; (C, F) biaxial vessels. (A–C) Immunofluroscence staining of elastin. Elastin, β-actin, and DAPI are in red, green, and blue, respectively. (D–F) TEM images of elastic fibers. Red arrows point to mature elastic fibers. Purple arrows indicate immature elastic fibers or microfibrils. (G) TEM image of elastic fibers of a human coronary artery. Red arrows point to mature elastic fibers. Purple arrows indicate immature elastic fibers or microfibrils. (H) Opening angle in degree (θ) both before and after elastase treatment (7.5 U/mL). Scale bars represent 36 μm in (A–C), 1 μm in (D–F). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n = 3, error bar ± SEM.

The maturity of elastic fibers in TEVs was further verified through TEM (Fig. 3D–F). The uniaxial TEVs formed short and segmented elastic fibers (Fig. 3E), whereas the static TEVs developed microfibril templates but failed to show elastin deposition onto the templates (Fig. 3D). Conversely, elastic fibers in the biaxial TEVs consisted of elastin cores and microfibril templates (Fig. 3F). The biaxial TEVs thus formed mature, long, and continuous elastic fibers that are similar to those of native coronary arteries (Fig. 3G). It is possible that the large number of segmented elastic fibers in the uniaxial TEVs corresponded to the high desmosine content.

In addition, the presence of fibronectin and fibrillin-1 was examined by immunostaining. All TEVs expressed fibronectin, a protein that is essential for assembly of fibrillin-144 (Supplementary Fig. S3). The biaxial TEVs expressed the most abundant fibrillin-1, whereas the static TEVs failed to form fibrillin-1. Mature elastin, along with fibrillin-1 and fibronectin, indicated mature elastic fibers in the biaxial TEVs. These findings suggest that mechanical stimulation is required for the synthesis of fibrillin-1, but not necessarily for the synthesis of fibronectin in those TEVs.

To assess the functionality of elastic fibers in terms of the development of residual stresses, opening angles were measured both before and after elastase treatment of isolated ring segments (Fig. 3H). Opening angles decreased significantly in the uniaxial and biaxial TEVs after elastase treatment (from 56° ± 2° to 15° ± 4°, p < 0.01; from 51° ± 4° to 26° ± 2°, p < 0.05, n = 3, respectively). No significant decrease in opening angle was observed in the static TEVs (from 27° ± 7° to 14° ± 5°, n = 3). A decrease in opening angle on the removal of elastin suggests that the elastic fibers played a role in developing the residual stresses in both uniaxial and biaxial TEVs.

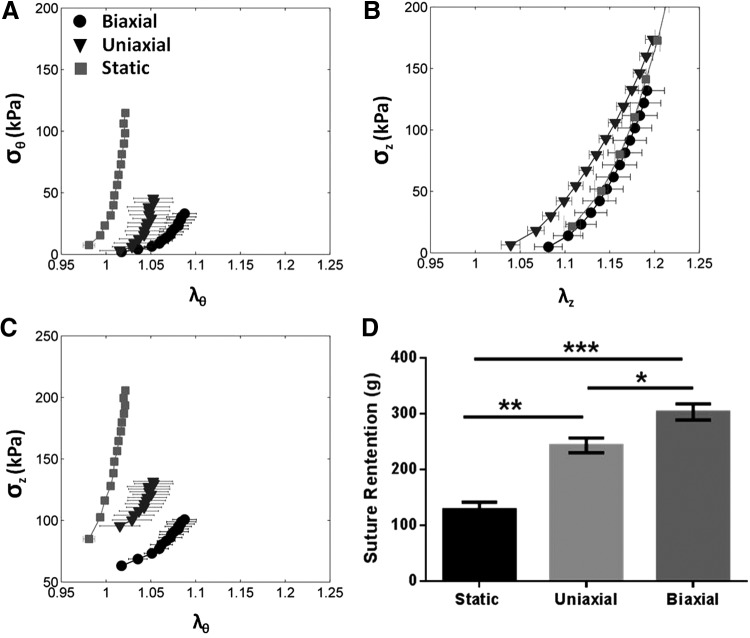

Biaxial stretching enhances vascular strength and compliance

The axial stretch ratio (λz, or extension ratio, defined as final length/initial length) was comparable among three groups (static: 1.35 ± 0.03, uniaxial: 1.19 ± 0.01, and biaxial: 1.28 ± 0.06), indicating no differences in recoiling properties of those TEVs. The biaxial TEVs demonstrated the highest suture retention strength (static: 128 ± 14 g, uniaxial: 243 ± 13 g, biaxial: 303 ± 15 g, n = 3, uniaxial vs. biaxial p < 0.05, static vs. uniaxial p < 0.01, static vs. biaxial p < 0.001) (Fig. 4D). The retention strength of the biaxial TEVs was comparable to that of native bovine arteries (273 ± 31 g)6 and higher than that for human arteries (200 g).45 Despite the difference in suture strength, the three TEV groups showed no statistically significant differences in collagen content (static: 54% ± 7%, uniaxial: 48% ± 5%, and biaxial: 67% ± 3% of dry weights, n = 3). Although the static TEVs had significantly smaller collagen fibril diameters than either biaxial or uniaxial TEVs (p < 0.01), no significant difference was observed in fibril diameter between the biaxial and the uniaxial TEVs (static: 43 ± 0.5 nm, uniaxial: 51 ± 1.3 nm, and biaxial: 50 ± 1.0 nm, n = 3) (Supplementary Fig. S1C).

FIG. 4.

Mechanical properties of biaxial TEVs. (A) Plot of circumferential stretch ratio versus circumferential stress (σθ vs. λθ). TEVs were pressurized to 140 mmHg and their bioreactor length. (B) Plot of axial stretch ratio versus axial stress (σz vs. λz). (C) Plot of circumferential stretch ratio versus axial stress (σz vs. λθ). n = 3 for static and the uniaxial TEVs, n = 2 for the biaxial TEVs. (D) Bar graph of suture retention strength of TEVs, n = 3. All data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The circumferential stress versus circumferential stretch (σθ vs. λθ) relationship obtained from biaxial mechanical tests was plotted to evaluate TEV distensibility under physiological pressures, up to 140 mmHg (Fig. 4A). The uniaxial and static TEVs were stiff and failed to exhibit a toe-region, whereas the biaxially conditioned TEVs displayed a nonlinear toe-region and more distensibility, both of which are characteristic of native arteries. Conversely, on examining axial stress–stretch relationships, all TEVs exhibited similar stretch relationships for the loads imposed (σz vs. λz) (Fig. 4B). In other words, despite differences in distensibility in the circumferential direction (Fig. 4A), all TEV groups showed comparable extensibility and all failed to display any associated toe-region in the axial direction (Fig. 4B). This finding was somewhat surprising given that the biaxial TEVs were subjected to higher cyclic strains in the axial direction. This may have resulted from the limited maximum stretch that was achieved during the mechanical tests, which was, in turn, restricted by the given capacity of the axial load cell. The axial stress versus circumferential stretch (σz vs. λθ) relationship showed changes in axial stress with an increase in TEV diameter (Fig. 4C), hence revealing a biaxial coupling. The biaxial TEVs showed the smallest increase in axial stress with increases in diameter, consistent with the highest compliance when compared with other TEVs.

The circumferential stress versus circumferential stretch (σθ vs. λθ) relationship of the biaxial TEVs both before and after elastase treatment is shown in Supplementary Figure S4. Removal of elastin via elastase caused a change in σθ versus λθ behavior of the biaxial TEVs as marked by a steeper slope at higher λθ (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Elastase treatment removed the majority of elastin in the TEVs, as evidenced by the lack of visible black filaments in the treated TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, the overall wall structure and integrity of the TEVs were not affected by the treatment. In contrast, elastase treatment had no effect on the stress–strain relationship in either the static or the uniaxial TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). These results suggest that elastic fibers had a small but notable effect on the stress–strain behavior of the biaxial TEVs but very little effect on the static or uniaxial TEVs.

To further understand what contributed to the observed compliance in the biaxial TEVs, we examined type III collagen by immunostaining, given that the elastin appeared to contribute little to vascular compliance. Type III collagen is commonly found in the arterial media and is associated with distensibility and/or extensibility.46 The expression of type III collagen progressively increased from static to uniaxial to biaxial mechanical conditioning (Supplementary Fig. S6). These outcomes suggest that, along with elastin, type III collagen might contribute to the observed higher compliance in the biaxial TEVs.

Biaxial stretching remodels transmural collagen organization

To examine collagen fiber structure, cross-sections of TEVs were divided into three layers (Supplementary Fig. S7A). SHG imaging revealed that collagen organization differed throughout the wall in all groups (Supplementary Fig. S8). In native arteries, fibers are axially oriented in the outer layers, and they are progressively more circumferential in inner layers (toward the lumen). The static TEVs showed little change in fiber orientation from outer to inner layers; each layer was composed of 42–48% anisotropically oriented fibers (arranged between 15° and 60°), and 46–50% axially oriented fibers (65°–90°). In uniaxial TEVs, collagen fibers were circumferentially aligned in the outer layers and became more axially oriented at the inner layers (Supplementary Fig. S8). In contrast, the biaxial TEVs showed axial collagen fibers in the outer and middle layers (48%), and they became progressively more circumferential in the inner layers, similar to that found in native arteries.24,25

This finding suggests that biaxial stretching led to a more physiologic organization of collagen in the TEVs relative to tissues that were cycled uniaxially.14,47,48 As previously seen in other biaxially stretched systems, this stretch-induced alignment can be overcome and produce tissues with more native-like matrix orientations.50,51 Our findings of increased mechanical and biochemical properties with biaxial loading are consistent with previous findings.50,51

A quantitative analysis of fiber orientation across the wall (Supplementary Fig. S7D–F) was consistent with the SHG images (Supplementary ig. S8). Collagen fibers were classified into three families depending on their angular dispersion25 (Supplementary Fig. S7B, C). Differences in fiber orientation among the TEV groups were not obvious in the outer layers but began emerging in the middle layers (Supplementary Fig. S7D–F). The biaxial TEVs showed consistently more anisotropic fibers (15°–60°) than the uniaxial TEVs in both the middle and inner layers. In the inner layers, biaxially stretched TEVs showed fewer helical–axial collagen fibers (65°–90°) than the uniaxial TEVs, as well as the most circumferential (0°–10°) collagen fibers. In other words, the uniaxial TEVs consisted of more axially oriented collagen fibers than the biaxial TEVs. Conversely, collagen fibers in the biaxial TEVs exhibited an organization more similar to that previously reported for native arteries.19,24,25

Biaxial stretching reinforces collagen undulation

Under birefringence, the majority of collagen fibers in all TEVs appeared red, suggesting mature collagen after 13 weeks of culture (Fig. 5). The static TEVs developed collagen fibers with a low degree of undulation (Fig. 5A); whereas this undulation was significantly reduced in the uniaxial TEVs, where most of the collagen fibers appeared straight (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, collagen undulation was higher in the biaxial TEVs than in either the static or uniaxial TEVs (Fig. 5E).

Removal of elastin via elastase reduced collagen undulation but had no adverse effect on the structural integrity of the collagen matrix. A similar loss of collagen undulation was observed in elastase-treated native arteries.35 This result suggests that elastic fibers found in the biaxial TEVs have a functional role in sustaining collagen fibers in an undulated state (Supplementary Fig. S9). Finally, collagen fibers of the biaxial TEVs developed a crimped structure (Supplementary Fig. S10C) that was similar to that in native arteries (Supplementary Fig. S10D), though this feature was largely absent in both static and uniaxial TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S10A, B).

Discussion

It is well known that mechanical conditioning is essential for growing TEVs with improved suture retention strength and burst pressure.4,30,49 Moreover, mechanical cues are necessary for maintaining the end-stage SMC contractile marker, smoothelin, a protein associated with a physiologic cell phenotype. We submit, however, that biaxial loading further enhances matrix development, producing more native-like TEVs with enhanced suture retention strength (Fig. 4D) and anisotropic (i.e., not entirely circumferential or axially aligned) collagen arrangement. Tissues that have preferential alignment in the circumferential or axial direction will have the capacity for large loads only in the preferred direction of the alignment.48 Therefore, it is advantageous in engineered tissues to have an anisotropic arrangement of fibers.

Cyclic loading (both uniaxial and biaxial) of TEVs increased cell number (cell proliferation) and enhanced smoothelin (an end-stage SMC contractile marker) expression relative to static conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2). Higher cell numbers correlated with greater elastin synthesis in cyclically loaded TEVs when compared with the static TEVs (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1B). However, only biaxial stretching (not uniaxial stretch alone) generated extensive and highly organized (Fig. 3F) elastic fibers (Fig. 3H and Supplementary Fig. S9) that contributed in a functional manner to vascular distensibility (Fig. 4A, C) and increased suture strength (Fig. 4D). Extensibility was, nevertheless, comparable among the three TEV groups. Hence, increased mechanical stresses enhanced both the contractile marker (smoothelin) expression and functional elastic fiber assembly, rather than simply producing disorganized elastin. However, they did not appear to enhance the axial recoil on removal of the TEVs from the bioreactor.

The biaxial loading induced an increase in mature elastic fibers that showed elastin cores supported by microfibril templates. On removal of these elastic fibers with elastase, the biaxial TEVs showed a significant decrease in opening angle and some vascular stiffening. The latter corresponded to the slight decrease in collagen undulation in the biaxial TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S9). These results indicate that biaxial stretching did enhance not only the presence but also the functionality of the elastic fibers.

Due to the limited availability of healthy arteries, veins and synthetic polymers continue to be used widely as arterial grafts.52,53 Mechanical mismatches of these grafts with the host arteries are considered to be primary contributors to graft failures.54,55 Such mismatches (e.g., compliance mismatch) can cause flow disturbances,56 which may contribute to intimal hyperplasia and thrombosis.57 Biaxial stretching slightly enhanced the nonlinear toe-region, and thus compliance of the TEVs studied here (Fig. 4.7A). Increasing graft compliance has been shown to improve graft patency.58 Thus, this enhancement resulted in more native-like mechanics that may, in turn, reduce graft failures in vivo.

Previous studies investigated the impact of mechanical cues on collagen structure and mechanics of engineered vascular constructs. Ultra-structural analysis of the collagen matrix suggests that cyclic circumferential strain promotes circumferential alignment of collagen fibrils in TEVs.19 Yeh and colleagues used a planar biaxial bioreactor to show that biaxial stretching realigned collagen fibers toward the direction between the maximum stretches in Cruciform-shaped collagen gels.59 Likewise, in this study, biaxial stretching yielded a more physiological organization of helical collagen fibers (15°–60°) in the TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S7E, F).24,25

The Tranquillo group showed that 60% axial retraction at the unfixed end of TEVs caused collagen fibers to realign toward the circumferential direction.12 Similarly, axial shortening during the cyclic biaxial load led to more circumferential fibers at the inner layers of the biaxial TEVs (Supplementary Fig. S7F). A combination of axial, helical, and circumferential fibers appears to provide improved adaptivity as well as stability against normal physiologic loading.60,61

Although not investigated in this study, it is clear from previous work that the cellular responses to uniaxial and biaxial stretching are markedly different in terms of matrix production and alignment. Balestrini et al. showed that fibroblasts orientated themselves in the direction of the stretch, and they remodeled their surrounding matrix that varied between uniaxially and biaxially deformed systems.62 Kaunas et al.63 demonstrated that after uniaxial cyclic load is applied, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is activated transiently; however, after biaxial load, activation of the JNK pathway is sustained. In cardiac fibroblasts, Lee et al.64 demonstrated that uniaxial strain produced increased activation of transforming growth factor-β1 relative to cells cycled under biaxial strain. Future studies will need to be performed to determine what regulatory mechanisms are governing the differential response of TEVs to biaxial stretch; however, it is clear that the biaxial conditioning directs resident SMCs to remodel their scaffold to a more functional blood vessel equivalent.

Conclusions

We designed a novel biaxial bioreactor that allowed us to study, for the first time, the impact of biaxial loading on TEVs in long-term (>3 months) culture. Effects of biaxial loading were assessed on ECM composition and structure as well as on mechanical properties in PGA-based TEVs cultured for 13 weeks. Biaxial stretching enhanced mature elastic fibers and compliance as well as biaxial strength. Hence, applying biaxial stresses is useful for constructing TEVs that exhibit mechanical functions and wall properties that are closer to those of native arteries than achieved with static conditions or cyclic uniaxial loading.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants NIH R01 HL083895-06A1 and U01 HL111016-01, both of which were to L.E.N.

Authors’ Contributions

A.H.H., J.D.H., and L.E.N. designed research; A.H.H., B.V.U., K.Z., L.Z., J.F., and B.S. performed research; A.H.H. and J.L.B. analyzed data; and A.H.H., J.L.B., and L.E.N. wrote the article.

Disclosure Statement

L.E.N. has a financial interest in Humacyte, Inc., a regenerative medicine company. Humacyte did not fund these studies, and Humacyte did not affect the design, interpretation, or reporting of any of the experiments here.

References

- 1.Diamantouros S.E., Hurtado-Aguilar L.G., Schmitz-Rode T., Mela P., and Jockenhoevel S. Pulsatile perfusion bioreactor system for durability testing and compliance estimation of tissue engineered vascular grafts. Ann Biomed Eng 41, 1979, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoerstrup S.P., Cummings Mrcs I., Lachat M., Schoen F.J., Jenni R., Leschka S., Neuenschwander S., Schmidt D., Mol A., Gunter C., Gossi M., Genoni M., and Zund G. Functional growth in tissue-engineered living, vascular grafts: follow-up at 100 weeks in a large animal model. Circulation 114, I159, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimitrievska S., Cai C., Weyers A., Balestrini J.L., Lin T., Sundaram S., Hatachi G., Spiegel D.A., Kyriakides T.R., Miao J., Li G., Niklason L.E., and Linhardt R.J. Click-coated, heparinized, decellularized vascular grafts. Acta Biomater 13, 177, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang A.H., and Niklason L.E. Engineering biological-based vascular grafts using a pulsatile bioreactor. J Vis Exp 52, 14, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niklason L.E., Abbott W., Gao J., Klagges B., Hirschi K.K., Ulubayram K., Conroy N., Jones R., Vasanawala A., Sanzgiri S., and Langer R. Morphologic and mechanical characteristics of engineered bovine arteries. J Vasc Surg 33, 628, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niklason L.E., Gao J., Abbott W.M., Hirschi K.K., Houser S., Marini R., and Langer R. Functional arteries grown in vitro. Science 284, 489, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isenberg B.C., Williams C., and Tranquillo R.T. Small-diameter artificial arteries engineered in vitro. Circ Res 98, 25, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahl S.L., Kypson A.P., Lawson J.H., Blum J.L., Strader J.T., Li Y., Manson R.J., Tente W.E., DiBernardo L., Hensley M.T., Carter R., Williams T.P., Prichard H.L., Dey M.S., Begelman K.G., and Niklason L.E. Readily available tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Sci Transl Med 3, 68ra9, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stewart S.F., and Lyman D.J. Effects of a vascular graft/natural artery compliance mismatch on pulsatile flow. J Biomech 25, 297, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies A.H., Magee T.R., Baird R.N., Sheffield E., and Horrocks M. Vein compliance: a preoperative indicator of vein morphology and of veins at risk of vascular graft stenosis. Br J Surg 79, 1019, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim D.H., Heo S.J., Kang Y.G., Shin J.W., Park S.H., and Shin J.W. Shear stress and circumferential stretch by pulsatile flow direct vascular endothelial lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells in engineered blood vessels. J Mater Sci Mater Med 27, 60, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syedain Z.H., Meier L.A., Bjork J.W., Lee A., and Tranquillo R.T. Implantable arterial grafts from human fibroblasts and fibrin using a multi-graft pulsed flow-stretch bioreactor with noninvasive strength monitoring. Biomaterials 32, 714, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn M.S., McHale M.K., Wang E., Schmedlen R.H., and West J.L. Physiologic pulsatile flow bioreactor conditioning of poly(ethylene glycol)-based tissue engineered vascular grafts. Ann Biomed Eng 35, 190, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhun C.S., Evans M.C., Barocas V.H., and Tranquillo R.T. Planar biaxial mechanical behavior of bioartificial tissues possessing prescribed fiber alignment. J Biomech Eng 131, 081006, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weidenhamer N.K., and Tranquillo R.T. Influence of cyclic mechanical stretch and tissue constraints on cellular and collagen alignment in fibroblast-derived cell sheets. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 19, 386, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girton T.S., Barocas V.H., and Tranquillo R.T. Confined compression of a tissue-equivalent: collagen fibril and cell alignment in response to anisotropic strain. J Biomech Eng 124, 568, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canham P.B., Finlay H.M., and Boughner D.R. Contrasting structure of the saphenous vein and internal mammary artery used as coronary bypass vessels. Cardiovasc Res 34, 557, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canham P.B., Talman E.A., Finlay H.M., and Dixon J.G. Medial collagen organization in human arteries of the heart and brain by polarized light microscopy. Connect Tissue Res 26, 121, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahl S.L., Vaughn M.E., and Niklason L.E. An ultrastructural analysis of collagen in tissue engineered arteries. Ann Biomed Eng 35, 1749, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson Z.S., Gotlieb A.I., and Langille B.L. Wall tissue remodeling regulates longitudinal tension in arteries. Circ Res 90, 918, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobrin P.B. Mechanical properties of arterises. Physiol Rev 58, 397, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey J.D., Eberth J.F., Dye W.W., and Gleason R.L. Fundamental role of axial stress in compensatory adaptations by arteries. J Biomech 42, 1, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark E.R. Studies on the growth of blood-vessels in the tail of the frog larva—by observation and experiment on the living animal. Am J Anat 23, 37, 1918 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bou-Gharios G., Ponticos M., Rajkumar V., and Abraham D. Extra-cellular matrix in vascular networks. Cell Prolif 37, 207, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzapfel G.A. Determination of material models for arterial walls from uniaxial extension tests and histological structure. J Theor Biol 238, 290, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dahl S.L., Vaughn M.E., Hu J.J., Driessen N.J., Baaijens F.P., Humphrey J.D., and Niklason L.E. A microstructurally motivated model of the mechanical behavior of tissue engineered blood vessels. Ann Biomed Eng 36, 1782, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mironov V., Kasyanov V., McAllister K., Oliver S., Sistino J., and Markwald R. Perfusion bioreactor for vascular tissue engineering with capacities for longitudinal stretch. J Craniofac Surg 14, 340, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaucha M.T., Raykin J., Wan W., Gauvin R., Auger F.A., Germain L., Michaels T.E., and Gleason R.L., Jr A novel cylindrical biaxial computer-controlled bioreactor and biomechanical testing device for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 15, 3331, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solan A., Mitchell S., Moses M., and Niklason L. Effect of pulse rate on collagen deposition in the tissue-engineered blood vessel. Tissue Eng 9, 579, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang A.H., Lee Y.U., Calle E.A., Boyle M., Starcher B.C., Humphrey J.D., and Niklason L.E. Design and use of a novel bioreactor for regeneration of biaxially stretched tissue-engineered vessels. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 21, 841, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woessner J.F., Jr The determination of hydroxyproline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch Biochem Biophys 93, 440, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piez KA L.R. The nature of collagen. In: Sognnaes R.F., eds. Calcification in Biological Systems: A Symposium presented at the Washington Meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, December29, 1958 Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1960, p. 411 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starcher B. A ninhydrin-based assay to quantitate the total protein content of tissue samples. Anal Biochem 292, 125, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starcher B., and Conrad M. A role for neutrophil elastase in the progression of solar elastosis. Connect Tissue Res 31, 133, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferruzzi J., Collins M.J., Yeh A.T., and Humphrey J.D. Mechanical assessment of elastin integrity in fibrillin-1-deficient carotid arteries: implications for Marfan syndrome. Cardiovasc Res 92, 287, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gleason R.L., Gray S.P., Wilson E., and Humphrey J.D. A multiaxial computer-controlled organ culture and biomechanical device for mouse carotid arteries. J Biomech Eng 126, 787, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberth J.F., Taucer A.I., Wilson E., and Humphrey J.D. Mechanics of carotid arteries in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Ann Biomed Eng 37, 1093, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dye W.W., Gleason R.L., Wilson E., and Humphrey J.D. Altered biomechanical properties of carotid arteries in two mouse models of muscular dystrophy. J Appl Physiol 103, 664, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calle E.A., Vesuna S., Dimitrievska S., Zhou K., Huang A., Zhao L., Niklason L.E., and Levene M.J. The use of optical clearing and multiphoton microscopy for investigation of three-dimensional tissue-engineered constructs. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16, 16, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinter J.P., and Levene M.J. Maximizing fluorescence collection efficiency in multiphoton microscopy. Opt Express 19, 15348, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broisat A., Toczek J., Mesnier N., Tracqui P., Ghezzi C., Ohayon J., and Riou L.M. Assessing low levels of mechanical stress in aortic atherosclerotic lesions from apolipoprotein E-/- mice—brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31, 1007, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fayad Z.A., Fuster V., Fallon J.T., Jayasundera T., Worthley S.G., Helft G., Aguinaldo J.G., Badimon J.J., and Sharma S.K. Noninvasive in vivo human coronary artery lumen and wall imaging using black-blood magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 102, 506, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Loop F.T., Schaart G., Timmer E.D., Ramaekers F.C., and van Eys G.J. Smoothelin, a novel cytoskeletal protein specific for smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol 134, 401, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabatier L., Chen D., Fagotto-Kaufmann C., Hubmacher D., McKee M.D., Annis D.S., Mosher D.F., and Reinhardt D.P. Fibrillin assembly requires fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell 20, 846, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.L'Heureux N., Dusserre N., Konig G., Victor B., Keire P., Wight T.N., Chronos N.A., Kyles A.E., Gregory C.R., Hoyt G., Robbins R.C., and McAllister T.N. Human tissue-engineered blood vessels for adult arterial revascularization. Nat Med 12, 361, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes M.J., and Farndale R.W. Collagens and atherosclerosis. Exp Gerontol 34, 513, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barocas V.H., Girton T.S., and Tranquillo R.T. Engineered alignment in media equivalents: magnetic prealignment and mandrel compaction. J Biomech Eng 120, 660, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tower T.T., Neidert M.R., and Tranquillo R.T. Fiber alignment imaging during mechanical testing of soft tissues. Ann Biomed Eng 30, 1221, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Isenberg B.C., and Tranquillo R.T. Long-term cyclic distention enhances the mechanical properties of collagen-based media-equivalents. Ann Biomed Eng 31, 937, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balestrini J.L., and Billiar K.L. Equibiaxial cyclic stretch stimulates fibroblasts to rapidly remodel fibrin. J Biomech 39, 2983, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balestrini J.L., and Billiar K.L. Magnitude and duration of stretch modulate fibroblast remodeling. J Biomech Eng 131, 051005, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Kurdi M.S., Hong Y., Stankus J.J., Soletti L., Wagner W.R., and Vorp D.A. Transient elastic support for vein grafts using a constricting microfibrillar polymer wrap. Biomaterials 29, 3213, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vijayan V., Shukla N., Johnson J.L., Gadsdon P., Angelini G.D., Smith F.C., Baird R., and Jeremy J.Y. Long-term reduction of medial and intimal thickening in porcine saphenous vein grafts with a polyglactin biodegradable external sheath. J Vasc Surg 40, 1011, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teng Z.Z., Ji G.Y., Chu H.J., Li Z.Y., Zou L.J., Xu Z.Y., and Huang S.D. Does PGA external stenting reduce compliance mismatch in venous grafts? Biomed Eng Online 6, 12, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kapadia M.R., Popowich D.A., and Kibbe M.R. Modified prosthetic vascular conduits. Circulation 117, 1873, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyawaki F., How T.V., and Annis D. Effect of compliance mismatch on flow disturbances in a model of an arterial graft replacement. Med Biol Eng Comput 28, 457, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart S.C., and Lyman D. Effects of an artery/vascular graft compliance mismatch on protein transport: a numerical study. Ann Biomed Eng 32, 991, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lehmann E.D. Vein compliance for preoperative assessment in vascular bypass surgery. Lancet 351, 1885, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu J.J., Humphrey J.D., and Yeh A.T. Characterization of engineered tissue development under biaxial stretch using nonlinear optical microscopy. Tissue Eng Part A 15, 1553, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cyron C., and Humphrey JD. Preferred fiber orientations in healthy arteries and veins understood from netting analysis. Math Mech Solids 6, 680, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balestrini J.L., Skorinko J.K., Hera A., Gaudette G.R., and Billiar K.L. Applying controlled non-uniform deformation for in vitro studies of cell mechanobiology. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 9, 329, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaunas R., Usami S., and Chien S. Regulation of stretch-induced JNK activation by stress fiber orientation. Cell Signal 18, 1924, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee A.A., Delhaas T., McCulloch A.D., and Villarreal F.J. Differential responses of adult cardiac fibroblasts to in vitro biaxial strain patterns. J Mol Cell Cardiol 31, 1833, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.