Abstract

The growing abundance of medical technologies has led to laments over doctors’ sensory de-skilling, technologies viewed as replacing diagnosis based on sensory acumen. The technique of percussion has become emblematic of the kinds of skills considered lost. While disappearing from wards, percussion is still taught in medical schools. By ethnographically following how percussion is taught to and learned by students, this article considers the kinds of bodies configured through this multisensory practice. I suggest that three kinds of bodies arise: skilled bodies; affected bodies; and resonating bodies. As these bodies are crafted, I argue that boundaries between bodies of novices and bodies they learn from blur. Attending to an overlooked dimension of bodily configurations in medicine, self-perception, I show that learning percussion functions not only to perpetuate diagnostic craft skills but also as a way of knowing of, and through, the resource always at hand; one’s own living breathing body.

Keywords: ethnography, materiality, medicine, senses

Before beginning this article, I would like you to try for yourself a medical technique called percussion. Perhaps you already know how to do it? If so, start straight away on the nearest fleshy or hard surface. For the novices, here are some instructions, adapted from a textbook called Clinical Examination by Nicholas Talley and Simon O’Connor.1 Beware, these instructions assume right-handedness and may be difficult for the directionally dyslexic! But have a go. First, raise your left hand to your upper chest wall and slightly separate the fingers (you can even align your fingers with the ribs if you can find them). Press the left middle finger firmly against the chest. Then, with the pad of the right middle finger, strike the middle phalanx (that’s the second ‘section’) of the middle finger of the left hand. Quickly remove the percussing finger so that the note generated is not dampened. Try it again. The percussing finger needs to be held partly fixed, and a loose swinging movement should come from the wrist, not the forearm. Move around to different parts of your chest and see if you notice any different sensations. Try to remember this technique and the sensations (the sounds, the vibrations, your body movements), or keep practising even, as you read this article, on different parts of your body, on a nearby table or arm of a chair.

Introduction

This article contributes to an ongoing discussion in the social sciences of the configuring of bodies in the practices of medicine (e.g. Casper, 1998; Hirschauer, 1991; Johnson, 2008; Michael and Rosengarten, 2012; Mol, 2002; Prentice, 2005; Taylor, 2005; Thompson, 2005). My case is the clinical examination technique of percussion. The article considers how a close study of the ways in which percussion is taught to, and learned by, novice doctors brings new insights into our understanding of how bodies are configured through craft skills, about the nature of sensory perception and the materiality of living bodies. As Davide Nicolini (2012) points out, drawing from Lave and Wenger (1994), studying how novices learn is a particularly good way to understand practice, as ‘old timers’ have the role of articulating practices, prying open their logics.

In medicine, percussion2 is one of the four steps in the basic clinical examination. Traditionally it is taught as coming after inspection and palpation, and before auscultation. It is a practice tied closely to doctors;3 perhaps more so than auscultation these days, with stethoscopes no longer markers of the medical profession in hospitals, used routinely also by physiotherapists and nurses. I largely limit my discussion in this article to percussion, although many themes raised would also apply to, and have contrasts with, other bodily practices in health care such as pulse taking (Daniel, 1984; Hsu, 2005), or the sensory techniques of ‘alternative bodyworkers’ such as reiki practitioners or masseuses (Barcan, 2011), which similarly deal with complicated notions of listening-touch.

Medical percussion has, like auscultation, an apocryphal story of invention. While René Laennec supposedly invented stethoscopic listening in 1816 when seeing some Parisian ‘street urchins’ playing with a log of wood, before this, in 1761, Leopold Auenbrugger is credited with inventing percussion after seeing his father tap wine barrels in his tavern basement. Some argue, however, that percussion was already being used by Auenbrugger’s teacher and others by the time he documented the technique (Jarcho, 1960; Volmar, 2013).4 Regardless of its accuracy, the invention story is an important one, often told to novices learning the technique. It is a story which emphasises the craftsmanship of percussion, tying it back to the skills of wine merchants and a sensory engagement with the material world.

As in other professions, craftsmanship is often emphasised when skills are perceived to be threatened by machines (Sennett, 2008). Recently, percussion has become somewhat emblematic of the kinds of skills considered lost in an era of technomedicine (Verghese, 2011). Laments over the deskilling of doctors have a longer history, with the introduction of new machines often wrapped up in ‘sensory politics’ (Rice, 2013). Technologies are viewed as replacing the senses in contemporary medicine, with blood pressure machines, ultrasounds, echocardiograms, X-rays and other investigations argued to replace practices involving touch, listening and more embodied approaches to care (Howes, 1995; Reiser, 1993; Verghese, 2011). Percussion thus takes on a political dimension in this context. It is important, therefore, to not assume the inherent value of teaching percussion, but to interrogate the kinds of bodies that learning this seemingly mundane practice brings into being.

I argue in this paper that three kinds of bodies arise from teaching and learning percussion: skilled bodies; affected bodies; and resonating bodies. Drawing from participant observation of clinical examination education in Australia and the Netherlands, including my learning with the students, interviews and textual analysis of teaching material, as well as my own experiences as a medical student and doctor, I flesh out these three bodies. I work first with Tim Ingold to examine processes of enskillment and the crafting of skilled bodies. I also turn to the work of Bruno Latour to explore how bodies are trained to be affected. These two theorists, both interested in sociomaterial practices, help to highlight important ways in which bodies are trained to know, and how knowing shapes bodies. Yet there is an aspect of how knowing and being interrelate which is overlooked in their work: self-perception.

Self-perception is neglected not only in these theories, but also many social studies of medicine, as well as those on the senses. However multisensory, perception is often regarded as something external to the self, as a way of perceiving the outside world, (two good exceptions being Tom Rice’s [2013] exploration of auto-auscultation and Drew Leder’s [1990] account of the absent body). In this article, I extend further from work on how bodies are trained to sense by examining what happens when practitioners attend to their own sensations and the sensory aspects of their interior. Looking at self-percussion, I show how students not only develop the muscles, nerves and body parts needed for percussion (wrists, fingertips, ears) but also livers and spleens and hearts and lungs. The student is both perceiver and perceived.

Much of the work to date on the configuration of bodies in medicine, in disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, history and science and technology studies (STS), assume an explicit distinction between practitioners’ bodies and the bodies practitioners work with (e.g. Hirschauer, 1991; Prentice, 2005; Twigg et al., 2011). Self-percussion blurs these boundaries between the bodies of novices learning their craft and the bodies they learn from. In this practice there is a sense of discovery as they tap out hollow and dull spaces, find ribs and lungs, organs and cavities, through sound and feel, crafting resonating bodies, pulsating, breathing, moving. Working predominantly with Merleau-Ponty’s (2002 [1945]) work on self-touch, towards the end of the article I consider the neglected practices of self-perception, whereby novices, in medicine but also by extension other crafts, learn through the pedagogical instrument always at hand; their own bodies, alive in movement.

Listening-touch

This article is based on fieldwork conducted in 2013, in a medical school and hospital in Melbourne, Australia, and in a Skills Lab in Maastricht, the Netherlands (see more about skills learning in this setting in Collins et al., 1997). Because of the timing of my research I encountered different moments in the learning process at each site. In Maastricht I spent time with novices in their first year of medical school, who were encountering the clinical examination for the first time (as practitioners). These students were learning in a laboratory environment, near to, but outside, the hospital. In Melbourne I also spent time with medical students in their first year, but they had already been learning examination techniques for the previous six months, and were revising the respiratory exam by the time I met them, rather than learning it for the first time. I also spent time with second, third and final year medical students on the wards, in tutorials, lecture theatres and cafeterias in Melbourne, as well as doctors and other hospital staff. In Melbourne I followed what was done and said, but in Maastricht, as I did not speak Dutch, I focused mostly on the bodily gestures rather than verbalisations (although some classes were taught in English). Throughout this article I intersperse practices from both sites, occasionally specifying something distinct to Maastricht or Melbourne when relevant.5

The primary aim of this research in medical schools and hospitals was to understand how doctors and other hospital staff listened to, and used, sounds in their work. This research was part of a larger project based in Maastricht (the Netherlands) about sonic skills across a range of professions.6 At first I concentrated on auscultation and the stethoscope, and the hospital soundscape. Doctors soon started emphasising to me though that percussion was about sound too.7 An email message in my inbox one morning from a professor of respiratory medicine articulates what others were telling me on the wards: ‘Percussion note is accurate in some settings, and in my view is a form of sound.’ I started to follow percussion more closely, focusing particularly on the respiratory examination.8 It was not long, however, before other doctors declared that the practice was not about sound at all, but about touch. Leaning back in his office chair, one professor of internal medicine declared: ‘I know this is contrary to your study but I could do percussion if I was deaf – it is about the feel of the percussion rather than the sound.’ More teachers and students told me that percussion was about the feeling of the vibration, rather than listening to the sound, especially in noisy hospital wards. It was not only that touch produced the sound, but also that the findings were felt through touch too, through listening fingers. There was no agreement about whether percussion was about sound or touch, and in the end it didn’t seem important: ‘We don’t just say “Now you’re listening. Now you’re looking. Now you’re feeling” it’s … it’s all integrated!’ one teacher in Melbourne exclaimed.

This intertwined nature of sound and touch in percussion reiterates the teaching of Auenbrugger. The clinical examination textbooks also emphasise the mingled nature of the sensory experience of percussion. For example, in a little yellow book stacked on top of any respectable medical student’s pile of ipads, clipboards and papers, The Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine instructions for percussion are given as follows:

Percuss all areas including the axillae, clavicles and supraclavicular areas. Listen and feel for the nature and symmetry of the sound. (Hope et al., 1996: 28, original emphasis)

Percussion is taught not only as a technique of listening or of touch only but both. Other textbooks reiterate this: ‘The feel of the percussion note is as important as its sound’, say Talley and O’Connor (1992: 111). ‘Percussion results in a complex set of signals giving the examiner both the auditory information of pitch and the tactile information of vibration or resistance, and reflects the ratio of air to solid structures under the area being percussed’, Cade and Pain (1988) further explain in the Essentials of Respiratory Medicine.

This intertwining of the senses treats touching and listening differently to many historical, sociological and anthropological studies of medical practice, which presuppose the senses as separate entities with corresponding sensory organs; the ears hear, the eyes see, fingers touch and so forth. These neat distinctions have been problematised over time. David Howes (2003) describes, for example, instances of intersense, a term that still retains some element of sensual separation. While Aristotle is often quoted as regarding the five senses as discrete, his work on common sense demonstrates an attempt to go beyond the five categories, to examine a mediating sense, by which we are sensing (Heller-Roazen, 2007: 44). Heller-Roazen follows the common sense through later philosophical work, writing that in later modernity, the classic problem of the central sense gained new urgency, reinterpreted as an inner touch, a sense of one’s vital movements, one’s sense that one is alive (Heller-Roazen, 2007: 250). This was a sense that could not be easily placed or described; for some it was skin, others viscera, muscles or blood, for others all things in a single moment (Heller-Roazen, 2007: 251).

The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1968: 134) and those inspired by his work dissolve further the notion of five senses, of eyes or ears as ‘separate keyboards for the registration of sensation’ (Ingold, 2000: 268), regarding them as organs of the body as a whole. Moving on from cognitive theories of perception, they argue that the lived body does not have senses but rather is sensible. As an example of how sensing occurs in unity, Merleau-Ponty focuses on how vision and touch are intertwined, through a crossing of the visible and tangible; a touch-vision system where looking and touching together make ‘my hands one sole organ of experience’ (Merleau-Ponty, 1968: 141). Ingold uses Merleau-Ponty to think of how the body responds to inflections in the environment to which it has been tuned, using examples such as interchangeable visual and auditory perceptions (Ingold, 2000: 277).

Like these sensory experiences in the phenomenological literature, my material so far (and perhaps your own experience?) has shown that percussion is simultaneously touch and listening, as well as the more ‘hidden’ sensation of proprioception (knowing where your finger is in relation to other parts of your body, when you perform the technique). Others have noted this fused nature of percussion, Jonathan Sterne (2003: 119) using the term ‘audible-tactile’ to describe the technique. Sterne (2006: 834) further deconstructs the notion of listening only with the ears, pointing out that we also listen through the chest and the head. Verrillo (1992: 296) examines listening through the skin’s vibrotactile system, offering a fascinating account of all of the parts of the body that a musician uses to detect tone. The details for the percussionist seem particularly pertinent here:

The tonal control exercised by percussive-instrument players takes place before the instrument is struck, because contact with the physical object is minimal, and through the kinesthetics of the arm-hand system, which also takes place largely before the sound is produced.

Listening-touch in percussion is not a single moment. As the finger-hand-wrist moves, the ear anticipates. The body works in coordination and listening-touch is distributed throughout the technique. Percussion entails anticipation, vibration, movement at the wrist, raising of the finger. As Massumi (2002: 155) argues, sensation happens in movement.

The phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty and his followers are important for highlighting the non-cognitive ways in which skills are learned in medicine, not as a process of acquisition and transmission, as is often presented in the medical education literature, but rather as an embodied process. Phenomenological theory also helps to underline the intertwined nature of the sensory experience of percussion – a practice that is an example of the multisensory work of medicine more generally – and I will return later to Merleau-Ponty’s work on self-touch particularly. However, the phenomenological literature does not sit entirely comfortably in this article, for there is some assumption in a lot of this work of a pre-existing body. As Annemarie Mol points out, rather than a body, there are bodies, configured through practices. Building on her earlier work on the enactment of bodies in medical settings, Mol (2002) examines this theme more recently with her collaborators studying eating, looking at the experience of tasting with fingers (Mann et al., 2011). Like the phenomenologists, these writers also point out that too often the senses are located in single organs – taste with the tongue in their case. In order to refute this, they set up an experiment in which the researchers eat a meal with their fingers. Their aim was to look at what these tasting practices may do, and the kinds of bodily specificities enacted. Unlike many phenomenologists, they were interested not in a body which preceded the self, but rather in the bodies which ‘arose from the occasion’ (Mann et al., 2011: 227). In this article I also examine bodies in medicine as arising through practices of percussion. I consider here the crafting of bodies, following from Simon Carmel’s (2013) definition of medicine as a craft9 – in the way in which medical work entails interactions with a material world and in the way in which it entails insightful and interpretive judgements. In the next two sections I look at how percussion is learned as a skilled interaction with the material world and then, following this, by looking at the insightful judgement learned through percussion, through training to be affected, focusing in both cases on the bodies which arise in these occasions.

Skilled Bodies: Becoming a Percussor

There are many classical strategies in teaching a craft which are used to teach percussion. I have already introduced textbooks as a means of describing the technique. Textbooks work as generalisers, mediators that summarise and record practices (Nicolini, 2012), extending the durability of a practice like percussion by propagating historical tales, offering diagrams and tips (van Drie, 2013). I spoke with two authors of the textbooks mentioned earlier in the article, Nicholas Talley and Michael Pain, and both reiterated how little had changed in their opinion with regard to the respiratory examination, including percussion, thus emphasising it as a time-honoured technique, a practice which spans place and time. The textbooks not only work generally but also work quite specifically and locally too. They are on reserve in libraries, borrowed, owned and shared, carried by students into their tutorials, on the wards, and in iphones. The complementary workbooks work mostly locally, being produced and copyrighted by each medical school. Both textbooks and workbooks outline, through written instruction and diagrams, what is involved in the technique. But as many theorists of craft, skill and tacit knowledge have argued (e.g. Collins, 2010; Ingold, 2000), we do not learn only from books.

Novices also learn ‘in practice’, and demonstrations in tutorials are an important part of this process (Harris and van Drie, forthcoming). Demonstration in medical education is a way of showing, a setting up of a situation so that novices can get a feel of it themselves (Ingold, 2000). In teaching percussion, the teachers demonstrate on themselves, on students or on skeletons. Then the novice has a go themselves, usually on a fellow student. Teachers instruct students to repeat the practice, over and over. It is not a natural technique for them. As one Melbourne teacher says:

a lot of people have no skill to draw on to explain it. If someone’s been a pianist and done staccato … then you can use that to explain what the right hand’s doing. But the left hand – when trying to get your middle phalanx flat – it is not a skill any of us have used in real life before.

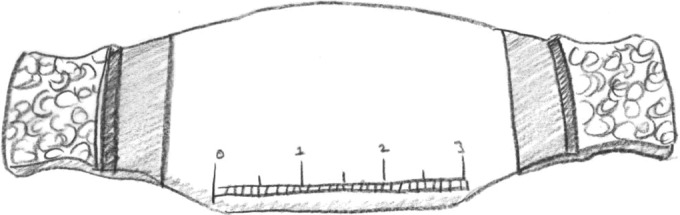

Not only have the students not done percussion before, but they’ve rarely seen it in action. This was evident in the early training sessions for first years I witnessed in Maastricht. The students had difficulty. One student used two fingers to percuss, another three tightly bound together. Another was too soft, another used her knuckles. One stabilised her percussion finger with another finger. Some were hesitant and others too gentle. Their fingers hurt and got tired. They start to notice them more, as their trained bodies came into being (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percussing hands.

Source: Author’s own drawing.

In these Maastricht tutorials the teachers were on hand to help correct techniques. As they assisted the student they tried to bring the novice closer to the practice. They might move a student’s finger in a particular way, making slight adjustments to reposition the student’s hands. One teacher in Melbourne said:

if they are really having trouble with positioning of their fingers I get them to hold their fingers and I tap their finger, so we can do both hands individually and build technique with left and right hand as separate beings.

The teachers show them the parts of the body they should ‘hit’, the pressure they should use or how to loosen the wrist, how hard to push and tap, which side of the bed to stand, how to stand so their back will not hurt or they do not look awkward. The teachers might advise students to cut their fingernails, so they avoid making gouges in their middle phalanges, and their bodies are further shaped. ‘It was hard to control my finger,’ one Dutch student told me in English, after her first session learning the technique, ‘but I learned from the teacher how to push harder.’ Throughout this process the teachers are demonstrating the technique again and again, demonstrating the kind of rhythm required. The students mimicked the teachers. In Melbourne, on the wards, I saw these techniques practiced on patients. A second year student percussed down one elderly man’s back, and her professor leaned in closely: ‘Low down you’ve hit a dull note haven’t you?’ he said. ‘We can all hear. Good wrist action Katherine, that’s good.’10

Through these techniques the novices’ bodies are crafted through repeated and learned movements. Ingold describes this process as enskillment, a way of learning through practical engagement with a world of materials. For Ingold, bodies exist in a dynamic ecological arrangement with tools and the environment, and are developed through skills. Learning, he writes, is a process whereby:

The novice watches, feels or listens to the movements of the expert and seeks – through repeated trials – to bring his own bodily movements into line with those of his attention so as to achieve the kind of rhythmic adjustment of perception and action that lies at the heart of fluent performance. (Ingold, 2001: 141)

These rhythmic gestures are not mechanical but rather set up through a ‘continual sensory attunement of the practitioner’s movements’ to their material world (Ingold, 2013: 115). Learning percussion is about learning to listen-touch bodies, with the whole body. The fingers, fingertips and phalanges are involved in the technique, as are the wrists. A teacher may regard the hands as ‘beings’ but my observations show that much more of the body is involved and the hands do not work separately. The elbow is not meant to do any work but the rest of the body also needs to be in the right position to not appear awkward, to not give back ache. Listening is not just through the ears, nor is touching just through the fingers; to paraphrase Kathryn Geurts’ (2003) translation of the Ghanaian phrase ‘seselelame’ as ‘feel-feel-at-flesh-inside’,11 this is body-listening-touch. Nowadays this technique uses the fleshy tools of the body, but it once involved intricate instruments such as wooden or ivory pleximeters (see Figure 2), percussion hammers, percussion thimbles and leather gloves (Jarcho, 1960: 168), advocated by doctors such as Pierre Piorry (Sakula, 1979) as ways of achieving measurable results.12 These instruments, though, never caught on, and for some time now the hand/fingers/wrist/body have been considered ‘the instrument’ of percussion.

Figure 2.

Ebony graduated ivory pleximeter.

Source: Author’s own drawing.

From this and the previous section we can see that the novice is trained in percussion through textbooks, demonstration, skeletons, mimicry and repeated practice. There were other materials involved too, such as YouTube videos, which students and teachers used. Through learning this technique, particular percussing bodies are brought into being. These are the skilled bodies of medical practitioners who are not awkward with other people’s bodies, who know how to stand near a hospital bed. The students are perpetuating a practice, learning how to perform one of the ‘time-honoured’ techniques of clinical examination.13 Crafted are bodies with chopped fingernails and ideally with calluses (Ingold, 2013; Sennett, 2008), like ink-stains on a writer’s hand. One teacher jokingly tells his students, ‘Unless you have a bump on your finger you haven’t done enough percussion!’ These bodies are not pre-given, but rather accomplished through training. Technologies were not absent from this process. There may no longer be thimbles, ebony plates and leather gloves, but there are textbooks, and diagrams, and YouTube videos which all mattered in learning the skill. In this section I have focused on learning the skill of percussion, and how, through fused listening-touch, the novice learns to engage with their materials; bodies. The next section examines how novices then learn something from the sensations produced by this technique, and develop skills in insightful judgement, the second aspect of craftwork which Carmel highlights.

Affected Bodies: Distinguishing Differences

Learning the technique of percussion and how to produce sensations is one aspect of the practice. It is also important for the young doctors, as future diagnosticians, to learn how to tell different sounds and textures apart, and to recognise similarities. Let’s return again to the little dog-eared and coffee-stained Oxford Handbook. Following the description of the technique described earlier in the article, the text instructs students to:

Distinguish between normal, resonant (hyperexpanded chest or pneumothorax), dull (over liver, consolidated lung) and stony dull (pleural effusion).

The novice must learn to distinguish between four categories of sensations – ‘normal’, resonant, dull and stony dull – learning the vocabulary associated with what they are listening to and feeling at the same time.14 The Maastricht workbook also encouraged this: ‘Describe your findings, try to use medical terminology.’ Like other practices, such as wine tasting (Shapin, 2012), this is about learning to be articulate. ‘I think a lot of it is also learning the words you should use to describe sound’, one student tells me. With regard to the description of percussion, little has changed since Auenbrugger’s use of the Latin terms ‘sonus altior’, ‘sonus obscurior’, ‘sonus prope suffocates’, ‘sonus percussae carnis’ which translate to the four categories listed above (Volmar, 2013), reflecting a conservatism and attempted preservation not only of percussive techniques, as we saw in the previous section, but also descriptions of the sensations produced. In Maastricht I observed when novices were first introduced to these words (in English and Dutch) through whiteboard teaching, as the teachers quizzed them on words they hoped the students had pre-read in the workbook. They tried hard to remember but some students got confused, answering with words that were reserved for other practices, such as auscultation. They needed ways in which to tie the words to sensations.

One method, in the tutorial room, was to use vocal mimicry: ‘Puck puck’ a teacher in Maastricht said as he traversed the skeleton on one side, then ‘Boom boom – boom boom, puck puck’. ‘What is that?’ He asked. ‘Boom boom?’ ‘Sonore’, a student answers. ‘Yes, and bum bum?’ ‘Tympany’, another said. The teachers start to fill in some anatomical detail. ‘Dull’, one student offered when quizzed. ‘Yes, that is no air, say over the liver’, the teacher said. ‘Tympany’, another replied. ‘Yes, that is when an organ has some air’. The textbooks also attempt to help the student to associate the sounds with the anatomical structures underneath the skin:

Percussion over a solid structure, such as the liver or a consolidated area of lung, produces a dull note. Percussion over a fluid-filled area, such as a pleural effusion, produces an extremely dull (stony dull) note. Percussion over the normal lung produces a resonant note and percussion over hollow structures, such as the bowel or a pneumothorax, produces a hyperresonant note. (Talley and O’Connor, 1992: 110)

Learning the words is one step, but associating them with sensory experiences is another. Just like flavourists, perfumers (Agapakis and Tolaas, 2012: 570) and other sensory experts, the medical students need to be trained to match sensations to words and types. For medical students, this happened on bodies. One way in which the teachers made this easier for students was by starting with large, obvious differences. A teacher in Maastricht showed his students the difference, for example, between the percussion note over the stomach and the clavicle (collar bone). This is an ‘artificial set-up’ (Latour, 2004) which is unlikely to appear in the clinic:15 ‘Clinically it’s not that important [to know the difference between the organs] – I want you to hear the difference between the sounds’, the teacher said. Another teacher told his students that the reason you do this is to listen to difference, ‘so that you are able to distinguish the difference between the sounds and say that this is sonorous and this is not sonorous’. So the students learn differences: between right lung and left lung (where the heart causes dullness), lung and liver, dull and resonant, clavicle and stomach. This distinguishing of difference happens on the wards too, particularly when being taught a technique called tidal percussion, which is performed at the bottom of the lungs, as the patient breathes in and out. A professor in Melbourne told me: ‘The beauty of percussion is that you can teach a student the difference between a dull note and a resonant note straight away. Because, as the patient takes a breath in, the note changes. From dull to resonant. So they pick up vibrations under their finger.’

As the students move through their training they learn smaller and smaller differences:

When you hit clinical school and the bedside they take you up to the really sick patients. The really obvious ones, so you can go ‘this is what abnormal sounds like’ and towards the end of the degree – which is where I am now – it’s like you’re listening to everyone. So … with some you will hear something but it could be completely normal because they’ve had it chronically and some would be very subtle … there’s less of the extreme ends of normal versus abnormal. There’s sort of the murky bits in the middle. (Final year medical student, Melbourne)

Latour (2004) discusses a similar process of learning differences with perfumers. In his discussion of Genevieve Teil’s work on the training of ‘noses’ for the perfume industry, he shows how when a novice perfumer is trained they use an odour kit to smell arranged fragrances that go from sharp to small contrasts. After a week, the new perfumer should be able to tell the difference between smells with slight differences, eventually even those mixed with other smells. As Latour writes, these artificial set-ups are created to attune the body (in his case ‘noses’) to differences, and to be moved into action by the contrast between the two. In order to understand this theoretically, Latour (2004) extends James Gibson’s notion of ‘an education of attention’ (a concept used extensively by Ingold) to examine how novice perfumers are ‘training to be affected.’ In this process of learning to be affected by previously unregisterable differences, ‘body parts are progressively acquired’ (Latour, 2004: 207). For Latour, the body is an interface that becomes further determined as it learns to be affected by more and more elements, whereby we become sensitive to what the world is made of. Before their teaching, the medical novices were also inarticulate – they couldn’t speak of the sounds of the body in the same way that Teil’s novice perfumers couldn’t speak about odours. They couldn’t tell the difference between hollow and dull spaces in the body. The students, in their percussion teaching, learn to be affected by differences they didn’t have the words to describe before: ‘Learning to be affected means exactly that: the more you learn, the more differences exist’ (Latour, 2004: 213). The body is trained to sense, to be sensible.16

While in medical school, students learn differences in each other’s bodies, in patients they are searching for pathologies. Pathological differences are more nuanced than those obvious differences in tutorial examples. Yet before a novice can detect smaller differences, they must be attuned to larger ones. They must not only discern differences but also similarities. One way in which the students are taught to do this is to find comparisons on their own bodies. This was demonstrated one day during ward teaching. We were standing in a cramped room in an acute medical care unit, and a student was performing a respiratory exam on an elderly woman. The teacher stopped to ask the student about her findings and a small lesson ensued. The professor instructed them on how to find sensations on their own bodies. First a particular kind of breath sound (bronchial breathing), by listening to their throats with their stethoscopes, a technique commonly used throughout my field sites. The patient looked on, amused. Then he taught them the sound of stony dullness by telling them to percuss their own thighs: ‘You can always go out and leave a patient and pretend you are going to the toilet or something. And percuss your thigh and that’s what stony dullness is. And it’s not only the sound, of course, it’s sort of the feel.’ I met many teachers who taught thigh percussion as a technique of comparison. Other parts of the body can be used too. The Wikipedia entry for percussion mentions hyperresonance (too much air) being like percussing puffed out cheeks. The body is a walking fleshy textbook of comparisons. As one student said to me: ‘You know, you’re always with you! So why not make use of your own anatomy!’ Back to the teacher on the wards, as he expands further about teaching self-percussion on the thigh:

I think it’s nice to have a resource like that, because it’s always there. You can always – you’ve always got a reference point – you can always come back to that.… Like stony dullness – there is nothing else that feels like it. Or sounds like that … feels like it. Nothing. So I think it is just a – a kind of resource that you carry with you – so you can always know what a normal percussion note is. Because you can do it on yourself. It’s a shortcut there.

Learning similarities and differences in percussion notes crafts the medical novices’ bodies in ways that go beyond enskillment; bodies are also brought into being through being affected by differences in the world. In the case of percussion, the affected bodies depend on the skilled bodies, for unlike the perfumers with their kits, the medical novices are making the sounds themselves, so technique matters. Another body also arises in the examples above: the novices’ anatomical body. The students are taught to use their bodies as ‘gold standards.’ It is not only sensing bodies which are crafted, but also the body parts that the medical student delineates through the practice. Here Ingold and Latour are somewhat limited in our exploration of this, for they are focused on perception of a world out there, rather than one’s own inner spaces. In the next section, through a more detailed exploration of self-percussion, I describe how the distinctions between perceiver and perceived are dissolved, as medical students tap out their own medical bodies.

Resonating Bodies: Discovering New Depths and Spaces

I am sitting around a tutorial table with a group of second year medical students in Melbourne, drinking coffee from the hospital café. They are talking about percussion:

Michael: I walk around tapping myself all the time.

Alex: I use the walls at home, because they’re hollow, so that’s good.

Simone: I sit on the loo and … (laughing) tap.

Clare: Yeah. It’s a good time isn’t it!

I saw many students practising on themselves throughout my fieldwork in Melbourne and Maastricht, sneaking taps on their stomachs during a tutorial, hitting their clavicles and thighs. One teacher told me a terrific story of self-percussion in the wilds of Africa. At the time a first year medical student, he was lying in his tent, in the middle of the bush, near his friend Edward, also a medical student:

It was dark and you could just hear these – you know – African bird calls and the occasional slightly strange noise and hope it wasn’t too near to the tent. There was silence and then in the next door tent I heard [he knocks on the table, laughs]. Edward, you’re practising your percussion now aren’t you!

These students are conducting a form of self-experimentation long-practised in medicine as a way of learning about bodies,17 discovering the sounds and textures of their own bodies. I also remember percussing myself all the time as a medical student. I do it now, while writing this article, and perhaps you may be doing it too as you read it, now you’ve been taught the skill and may have started to notice some interesting differences.

Learning on one’s own body is something rarely acknowledged in studies of medicine. There is much emphasis on learning from other bodies – corpses in dissection theatres (Richardson, 1987), anaesthetised (Hirschauer, 1991) or simulated patients (Bradley, 2006; Taylor, 2014), mannequins (Cooper and Taqueti, 2008; Johnson, 2008), models of body parts (Hardy, 2013), bodies in formaldehyde jars, patients on the wards – so learning on the one resource that is close to hand is often neglected. In the literature just cited, two different bodies, the trained practitioner’s body and the body learned on, are separated. There is little mention of self-perception. Rice (2013: 137) is an exception, for he examines the practice of auto-auscultation, when, through the stethoscope, the patient or student creates a sensory engagement not with an abstract body, but with their own body. Rice importantly calls attention to the sounds dwelling in the listener, which complicate clear distinctions between interiority and exteriority.

Self-perception not only blurs boundaries between internal and external but also complicates clear distinctions between self and others. It is useful, in thinking through the practice of self-percussion, to return briefly to Merleau-Ponty’s (1968, 2002 [1945]) work. In Phenomenology of Perception the philosopher first introduces his exploration of self-touch, elaborated on much further in The Visible and Invisible, one of the last (unfinished) pieces of writing he was working on before he died. Self-touch is best demonstrated in the simple movement of one hand touching another. This movement, for Merleau-Ponty, highlights the intertwining and divergence of flesh, body as object and subject as the hands are felt from within and from without. Each hand in turn, takes its place among the things it touches, for Merleau-Ponty (1968: 133), demonstrating that our bodies are of the world around us, caught up in its tissue. We are both touched and touching, perceived and perceiver at the same time.

This dissolution of the perceiver and perceived, I believe, is an important point to keep hold of, even if we abandon the notion of a preconceived body. For the act of self-touch highlights that our own bodies are not just loci of sensory perceptions, however intertwined, but are also built through these perceptions. Through self-percussion, I suggest, to paraphrase Merleau-Ponty (1968: 143), the students turn themselves anatomically inside out, a process eloquently described in this passage by the author and physician Abraham Verghese (1994: 337).18

I was taught how to percuss the body so long ago…. That night, like tonight, lying flat on my back, the sheets pulled away and the lights off, I percussed my liver. I started just above my right lung, high, at the level of my nipple, pressing the middle finger of my left hand against my skin. I cocked my right wrist and let the fingertips fall like piano hammers: thoom, thoom. ‘Resonance’ I said to myself, picturing the air vibrating in a million air sacs, a million tiny tambours. I moved down an inch: thoom, thoom. Farther down and farther still, and then suddenly, thunk! thunk! – dullness. I had reached my liver, airless and solid. I returned to my nipple: thoom, thoom, thoom, thoom, and then thunk! I lightened my stroke: there was no longer any sound but there was still a vibration in my stationary finger – the pleximeter finger – which told me where the air sacs ended and where, high under my rib cage, under the domed diaphragm, my liver began… As a young medical student, I percussed everything in the joy of discovery. I percussed table tops, to find the stony dull circle where the leg joined the underside. I percussed plaster walls, looking for studs. I percussed tins of rice flour and the sides of filing cabinets. But in the dark, just as tonight, it was my own body that I percussed. As I drifted to sleep I saw myself as if transparent, my viscera, both hollow and solid, shining through my skin.

Through percussion it is as if, as Verghese writes, students’ viscera become visible under their epidermal cover. The student’s inner spaces become sonic caves textured with pulsating organs, creaking fibrous tissues and vibrating alveoli. The body is a resonating19 chamber,20 a living breathing body, one in constant movement (Massumi, 2002; Merleau-Ponty, 2002 [1945]). The inner body is realigned spatially and in the imagination, ‘fleshed out’ through an ‘inner touch’ (Heller-Roazan, 2007), in a way that carves out a new shining visceral materiality.21 Here percussion crafts a third kind of body; resonating bodies, which breathe and pulse, bodies thick with air and fluid, arising not from visceral ‘depth-disappearance’, as Leder (1990) discusses, but rather a heightened awareness of depth and voids. For the students there is a sense of joy in these inner space discoveries which extends to when they percuss walls and tins and table legs, and each other too: ‘This should be tympany, but now it is dull’, one Maastricht student exclaims to another. ‘But there can’t be lung there any more! Maybe your intestines are very high!’ Through percussion, the students’ living bodies are dissected from the outside, portioned into parts without the need of scalpels and retractors. ‘That’s lung’, the teacher shows them, percussing, ‘that’s mixed’, ‘that’s dull.’ ‘Oh wow, the liver is really high! That’s shocking!’ This new knowledge is shocking. Another student told me after a percussion session, ‘The lungs are really big when you breathe in!’

The practice of percussion helps to craft the anatomical and physiological materiality of students’ bodies. In the Maastricht tutorial sessions, anatomical borders are traced on skin surfaces with eyeliner pencils as the students draw where the lungs end and other organs begin, the markings moving with breath. The students draw on their bodies with soft gentle strokes like a tailor chalking fabric, an anatomist helping to explain the organs underneath. The students walk around at the end of the session with numbers marked down their spine.22

The resonating bodies the students percuss become criss-crossed with surface markings and lines showing newly discovered inner spaces. The students are not only discovering anatomical and physiological detail of underlying viscera, but are, I suggest, developing a perception of their ‘own vitality, one’s sense of aliveness’ (Massumi, 2002: 36). This is not a corpse or a body part in a jar nor the abstract bodies in textbooks that Hirschauer (1991) describes surgeons learning from. In the vitalist sense, this is a body in movement. The students are listening and feeling their own vitality, just as Mol and her colleagues (Mann et al., 2011: 239) tasted theirs, bringing their bodies into being through sensing in movement. And as Verghese describes in his story above, there are not only human bodies to discover but, in fact, a whole world to percuss: tables and walls and, as the students tell me, cats and dogs too.

The students are bodies among other human and other-than-human bodies. The medical student becomes more aware of, resonates with (Latour, 2004), these other bodies in part by crafting their own bodies, the nearest to hand, literally in the case of percussion, an arm’s length away. As Merleau-Ponty (1968: 145) writes, ‘the factual presence of other bodies could not produce thought or the idea if its seed were not in my own body’. Karen Barad (2012: 1) takes this further, in her consideration of self-touch, which she suggests might:

not enliven an uncanny sense of the otherness of the self, a literal holding oneself at a distance in the sensation of contact, the greeting of the stranger within? So much happens in a touch: an infinity of others – other beings, other spaces, other times – are aroused.

In learning percussion future patients’ bodies become possible too.

Through percussion, medical students learn the craft skills important for becoming good diagnosticians: bodily techniques for eliciting signs; discernment of sensory differences or similarities; and, finally, awareness of the anatomical body in movement, their own and a potential sensibility for other bodies as well, the ‘strangers within’. Through knowing themselves, the students can know others too. This section of the article has highlighted how knowledge of bodies is inextricably tied up with the students’ own material bodies. Not only does the student train sensing fingers, wrist joints and ears but they also craft their own topographical bodies. These are bodies missing from other studies of medicine mentioned in this article, a bodily materiality also somewhat absent from the work of Ingold and Latour. Through learning percussion, skilled bodies, affected bodies and resonating bodies are crafted, relying on each other. Knowing and being cannot be separated. A new way of being is necessary for a new way of knowing to become possible, and a new way of knowing shapes the new way of being. Bodies emerge, in movement, and are shaped by what the medical students come to know and their own materiality simultaneously.

Conclusion

In this article I have discussed the teaching and learning of a medical skill, percussion, and the kinds of bodies which arose from these occasions. In doing so I have addressed Barad’s (2003) call to consider carefully how material bodies come together with practices to mutually produce each other, contributing to an ongoing discussion on the configuration of bodies in medicine. How do the three bodies described in this paper interrelate? To create sensations to compare, skilled bodies must be trained. When learning to discern differences and similarities through skilled movements, bodies become experimental spaces. Through practices of self-percussion not only are new depths and spaces found in resonating chambers, but also others’ bodies, bodies of living, breathing future patients, become possible to explore as well. This further configures skilled bodies, for the clinical skills taught in medical school entail not only technical ability (skills) and diagnostic ability (being affected by difference/similarity) but also an imagining of others.

My empirical examples of how these bodies are crafted have centred around pedagogical events. As I have pointed out, one of the aims of teaching percussion is to train good diagnosticians. Percussion is a skill to be taken onto wards and into clinics. During my hospital fieldwork, however, percussion was not often performed; only occasionally by the respiratory physicians, mostly during morning rounds. The practice of percussion, it might be argued, performs primarily a pedagogical purpose, to educate doctors into being doctors, into their medical identities and to reproduce medical practices at the same time. Learning percussion, as well as the self-knowledge of one’s own body discovered through it, is part of belonging to a community and profession (Lave and Wenger, 1994). Teaching percussion helps to conserve medical knowledge in bodies and maintain time-honoured craft traditions. Those involved in the sensory politics debate argue that we should continue to teach percussion in order to foster clinical skills in a medical world increasingly filled with machines. Yet, as I showed in this article, the practice of percussion is inseparable from the field of technological relations which constitute it – from the YouTube videos (some of which are made by Verghese himself), the pleximeters and the textbooks for example.

No, I do not suggest here that percussion is an antidote to technomedicine. But perhaps learning clinical skills such as percussion has a role which has to date been largely overlooked – that of experimentation and discovery. The medical students learned about bodies through their own bodies, living, breathing, ready to be sensed as well as sensing, always at hand to learn from. Perhaps you, the reader, also learned more about the arguments I proposed in this article by performing the practice yourself, on yourself? Such forms of self-discovery should be taken more seriously, not only in medical education but also in the teaching of sensory skills more broadly. In doing so, the materiality of bodies comes to the fore, dissolving boundaries between the perceiver and the perceived, the skilled expert and the object of learning, highlighting how perception is not only of something external to the self, but can also be internal and inextricably tied up with the cultivation of one’s own body and other bodies. Perception is not, or not always, a registration of some world out there by means of separated sensory organs, but rather an intricate engagement in which knower and known are crafted together, through sensing in movement.

Acknowledgements

The research upon which this article is based is part of the Sonic Skills: Sound and Listening in the Development of Science, Technology, Medicine (1920–now) project funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), from a Vici Grant awarded to Karin Bijsterveld. I would like to thank the Sonic Skills team (Karin Bijsterveld, Joeri Bruyninckx, Stefan Krebs, Alexandra Supper and Melissa van Drie) for their collegiality and comments; the Department of Technology and Society Studies Summer Harvest 2014 group for the rich discussion, especially Govert Valkenburg for an excellent commentary; the Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT, for hosting me during fieldwork in Melbourne and for a wonderful exchange of ideas during their seminar series, especially Tania Lewis and Sarah Pink for their comments on percussion; Eleanor Flynn, Peter Morley, Jan-Joost Rethans and Karin te Sligte for helping me set up this research and their insights. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers who provided excellent comments for me to work with to improve the article. Above all, I would like to thank the students and teachers in Melbourne and Maastricht who so generously shared their time, sounds and many other fascinating things with me during fieldwork.

Biography

Anna Harris is an anthropologist of medical practices. She studies how bodies and technologies get entangled and play out in different settings of medicine, with a focus on issues of sensoriality, embodiment and learning. Her research crosses the fields of anthropology, science and technology studies, medical education, medical humanities and health sociology. She blogs regularly about an intriguing hospital infrastructure at: www.pneumaticpost.blogspot.com.

Notes

All of the textbooks mentioned in this article are chosen because they were used by participants in my study. The references are to editions that I used as a medical student, and still have on my bookshelf, although there have now been updated versions of these books. See van Drie (2013) for a discussion of how medical textbooks have changed over time in regard to teaching sonic skills.

Two theories have been proposed to explain the phenomena resulting from percussion. The first is the topographic percussion theory, where percussion causes vibrations in underlying structures, and sound waves are reflected, refracted and absorbed according to the density of underlying structures. The second is the cage resonance theory where percussion sound is thought to reflect the ease with which the body wall vibrates (Wong et al., 2009: 312). Steven McGee (1995), one of the main figures of evidence-based diagnosis, follows the second theory, arguing that the percussion note reflects the ease with which the wall vibrates, and is affected by strength of stroke, condition and state of body and underlying organs.

Throughout the course of my fieldwork, while I saw many nurses with stethoscopes and some performing auscultation, I did not see any percuss, nor any of the other allied health professionals. From my brief examination of nurses’ teaching manuals on the wards I spent time on, I also did not find the same attention to percussion as there was in the neighbouring medical workbooks and textbooks.

Regardless of when it was first used, Auenbrugger was the first to document percussion. The adoption of the technique in medicine, however, was slow and uncertain before 1820, due in part to Auenbrugger’s short, incomplete treatise, in Latin, which did not provide a clear explanation, as well as the physician’s own reluctance to promote the technique and, perhaps most importantly, the lack of a general consideration of disease as localised phenomena at that time (Sterne, 2001: 124–5). It was only when Corvisart, a strong advocate of the clinical exam, translated Auenbrugger’s work into French that percussion was introduced, into an era of medicine where physical examination of the body had replaced listening to patients’ stories (Volmar, 2013). Percussion was part of a great turn in medical practice, towards attending to signs as well as symptoms of disease. The history of the senses is a vast body of literature. For a history of the senses in medical diagnosis, such as urine tasting and pulse taking, see Bynum and Porter’s (2005) Medicine and the Five Senses or, more recently, Howes and Classen’s (2014) Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society. For more detail on the rise of physical examination in Western medicine in the 19th century and the role of touch in particular, see especially Porter (2005).

There are, as Lachmund (1999) and others point out, geographical distinctions between how such clinical skills are taught and have developed in medicine, and I certainly do not imply that the practice of percussion is ‘universal’. However, cultural differences in the practice between Melbourne and Maastricht are not my focus here.

This Dutch (NWO, VICI) funded research project – Sonic Skills: Sound and Listening in the Development of Science, Technology, Medicine (1920–now) – is led by Karin Bijsterveld. It also includes other sub-projects by Joeri Bruyninckx, Stefan Krebs, Alexandra Supper and Melissa van Drie that empirically investigate the role of sound and listening in knowledge production.

Surprisingly, percussion has received little attention in the social sciences, even in social studies of medical practice. In discussions of sensory practice involving sound, auscultation is the most used example (e.g. Lachmund, 1999; Rice, 2013; Sterne, 2003; Volmar, 2013). While percussion is mentioned in some of this work, it is not the focus of analysis. This may be for a number of reasons: the emphasis in some cases on cardiac medicine, where percussion is not so common; the focus on clinical rather than pre-clinical training of medical students; or it may indicate a general trend in some of these studies to focus on medical techniques through technologies of listening.

Percussion is also conducted in the cardiac and abdominal examinations of the body; however, it performs only a minor role in these examinations and I focus here on the respiratory examination where it is more prominent. My focus during fieldwork was on respiratory medicine.

Medicine has also been described as a craft by others, such as Hirschauer (1991), who likens medicine to building and carpentry, tailoring, sailors’ knots and the butcher’s trade. More generally Latour and Woolgar (1979) also discuss craftwork in science, Fujimura (1992) examines crafting of science, and Kondo (1990) the crafting of selves in the Japanese workplace.

All names used in the article, except for the authors of textbooks, are pseudonyms.

My thanks to a reviewer for pointing this connection out to me.

Roy Porter (2005:179) suggests that instruments used at this time in medicine may have also reduced a sense of violation and undesired intimacy.

Others have written about this through the lens of Bourdieu’s habitus. See for example, Rice (2013) and Sinclair (1997).

For a historical perspective on this issue see Lawrence (2005), who writes about the learning of a sensory vocabulary in medicine by looking at how London lecturers of the 18th and 19th centuries educated the senses.

Topographical percussion, although advocated by many such as Verghese, is argued to have little clinical utility, and advocates of evidence-based medicine recommend abandoning it (McGee, 1995).

See also Bleakley and colleagues (2003), for their work on visual judgement in medical education as a form of sensory connoisseurship.

For example, the self-experimentation of the doctor Werner Forssmann made the heart visible by catheterisation (Kerridge, 2003).

In the US, Abraham Verghese is an instrumental figure in the push for better clinical examination teaching and the sensory practices of medicine. He bemoans the lost art of percussion, shocked that internists can be certified in the US without being able to detect a pleural effusion by percussion (Verghese, 2009). In efforts towards comparable testing, doctors are now tested on standardised patients who do not have clinical signs, meaning that skills such as percussion cannot be tested.

Resonance has a number of different meanings which could apply here: it refers to the quality of sound, a quality that makes something meaningful, a sound vibration in one object caused by sound vibration produced in another, a sensation produced from percussion and finally, in social theory, to an incorporeal intensity (Massumi, 2002).

The body as a resonant chamber is also discussed by Brian Massumi (2002) and Jean-Luc Nancy (2007).

An interesting contrast could be made here to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioners who regard the entire body to be responsive, expressive and a site of memory – rather than focusing on localised areas and symptoms they regard the spaces of the body differently, in terms of fluids, flows and energy rather than a mass of bones, muscles and viscera (Barcan, 2011).

The 18th-century physician Pierre Piorry also used to draw on his patients’ skin, using coloured crayons, to outline his findings from percussion, a mapping he called l’organographism. Piorry was quite flamboyant in his approach to percussion teaching. He tried to convince observers that every organ had a separate sound, playing his pleximeter like a virtuoso. There is a charming story, which surely can’t be true, that he once visited the Royal Palace in the Tuilleries and demanded to see the king. Upon being told the king wasn’t there, Piorry brought out his pleximeter and percussed the king’s closed door. The story goes that he detected a certain dull sound and diagnosed the presence of the king in his chamber (Sakula, 1979)!

References

- Agapakis C, Tolaas S. (2012) Smelling in multiple dimensions. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 16: 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barad K. (2003) Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(3): 801–831. [Google Scholar]

- Barad K. (2012) On touching: The inhuman that therefore I am In: Witzgall S. (ed.) The Politics of Materiality. Available at: http://womenstudies.duke.edu/uploads/media_items/on-touching-the-inhuman-that-therefore-i-am-v1-1.original.pdf (accessed 25 August 2014).

- Barcan R. (2011) Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Bodies, Therapies, Senses. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Farrow R, Gould D, Marshall R. (2003) Making sense of clinical reasoning: Judgement and the evidence of the senses. Medical Education 37(6): 544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. (2006) The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Medical Education 40(3): 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum WF, Porter R. (2005) Medicine and the Five Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cade JF, Pain MCF. (1988) Essentials of Respiratory Medicine. Oxford: Blackwell Science. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel S. (2013) The craft of intensive care medicine. Sociology of Health & Illness 35(5): 731–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper MJ. (1998) The Making of the Unborn Patient: A Social Anatomy of Fetal Surgery. London: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins HM. (2010) Tacit and Explicit Knowledge. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins HM, de Vries GH, Bijker WE. (1997) Ways of going on: An analysis of skill applied to medical practice. Science, Technology & Human Values 22(3): 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JB, Taqueti VR. (2008) A brief history of the development of mannequin simulators for clinical education and training. Postgraduate Medical Journal 84: 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel EV. (1984) The pulse as an icon in Siddha medicine In: Daniel EV, Pugh JF. (eds) Contributions to Asian Studies 18 Leiden: Brill, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura J. (1992) Crafting science: Standardised packages, boundary objects, and ‘translation’ In: Pickering A. (ed.) Science as Practice and Culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 168–214. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts K. (2003) Culture and the Senses: Bodily Ways of Knowing in an African Community. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy KA. (2013) The education of affect: Anatomical replicas and ‘feeling fat’. Body & Society 19(1): 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, van Drie M. (forthcoming) Sharing sound: Teaching, learning and researching sonic skills Sound Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Heller-Roazen D. (2007) The Inner Touch: Archaeology of a Sensation. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschauer S. (1991) The manufacture of bodies in surgery. Social Studies of Science 21(2): 279–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hope RA, Longmore JM, Hodgetts TJ, Ramrakha PS. (1996) Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howes D. (1995) The senses in medicine. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 19: 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Howes D. (2003) Sensual Relations: Engaging the Senses in Culture and Social Theory. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howes D, Classen C. (2014) Ways of Sensing: Understanding the Senses in Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu E. (2005) Tactility and the body in early Chinese medicine. Science in Context 18: 7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold T. (2000) The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold T. (2001) From the transmission of representations to the education of attention In: Whitehouse H. (ed.) The Debated Mind: Evolutionary Psychology Versus Ethnography. Oxford: Berg, 113–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold T. (2013) Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jarcho S. (1960) Auenbrugger, Laennec, and John Keats. Speech at the Annual Banquet of the Osler Society of McGill University. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson E. (2008) Simulating medical patients and practices: Bodies and the construction of valid medical simulators. Body & Society 14(3): 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge I. (2003) Altruism or reckless curiosity? A brief history of self experimentation in medicine. Internal Medicine Journal 33(4): 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo D. (1990) Crafting Selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmund J. (1999) Making sense of sound: Auscultation and lung sound codification in nineteenth-century French and German medicine. Science, Technology, & Human Values 24(4): 419–450. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. (2004) How to talk about the body? The normative dimension of science studies. Body & Society 10(2/3): 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Latour B, Woolgar S. (1979) Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lave J, Wenger E. (1994) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SC. (2005) Educating the senses: Students, teachers and medical rhetoric in eighteenth-century London In: Bynum WF, Porter R. (eds) Medicine and the Five Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 154–178. [Google Scholar]

- Leder D. (1990) The Absent Body. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mann A, Mol A, Satalkar P, Savirani A, Selim N, Yates-Doerr E. (2011) Mixing methods, tasting fingers: Notes on an ethnographic experiment. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 1(1): 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi B. (2002) Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGee SR. (1995) Percussion and physical diagnosis: Separating myth from science. Disease a Month 41(10): 641–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. (1968) The Visible and the Invisible. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. (2002. [1945]) Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Michael M, Rosengarten M. (2012) Medicine: Experimentation, politics, emergent bodies. Body & Society 18(3–4): 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mol A. (2002) The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy J. (2007) Listening. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini D. (2012) Practice Theory, Work, and Organization: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porter R. (2005) The rise of physical examination In: Bynum WF, Porter R. (eds) Medicine and the Five Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice R. (2005) The anatomy of a surgical simulation: The mutual articulation of bodies in and through the machine. Social Studies of Science 35(6): 837–866. [Google Scholar]

- Reiser S. (1993) Technology and the use of the senses in twentieth-century medicine In: Bynum WF, Porter R. (eds) Medicine and the Five Senses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rice T. (2013) Hearing and the Hospital: Sound, Listening, Knowledge and Experience. Canon Pyon: Sean Kingston Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson R. (1987) Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sakula A. (1979) Pierre Adolphe Piorry (1794–1879): Pioneer of percussion and pleximetry. Thorax 34: 575–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennett R. (2008) The Craftsman. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shapin S. (2012) The tastes of wine: Towards a cultural history. Rivista di Estetica 51: 49–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S. (1997) Making Doctors: An Institutional Apprenticeship. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J. (2001) Mediate auscultation, the stethoscope, and the ‘autopsy of the living’: Medicine’s acoustic culture. Journal of Medical Humanities 22(2): 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J. (2003) The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J. (2006) The mp3 as cultural artifact. New Media & Society 8(5): 825–842. [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, O’Connor S. (1992) Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis, 3rd edn. Sydney: Maclennan and Petty. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS. (2005) Surfacing the body interior. Annual Review of Anthropology 34(1): 741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS. (2014) The demise of the bumbler and the crock: From experience to accountability in medical education and ethnography. American Anthropologist 116(3): 523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. (2005) Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twigg J, Wolkowitz C, Cohen RL, Nettleton S. (2011) Conceptualising body work in health and social care. Sociology of Health & Illness 33(2): 171–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Drie M. (2013) Training the auscultative ear: Medical textbooks and teaching tapes (1950–2010). The Senses and Society 8(2): 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Verghese A. (1994) My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story of a Town and Its People in the Age of AIDS. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Verghese A. (2009) In praise of the physical examination. British Medical Journal 339: b5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese A. (2011) Treat the patient, not the CT scan. New York Times 26 February. [Google Scholar]

- Verrillo R. (1992) Vibration sensation in humans. Music Perception 9(3): 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Volmar A. (2013) Sonic facts for sound arguments: Medicine, experimental physiology, and the auditory construction of knowledge in the 19th century. Journal of Sonic Studies 4(1). [Google Scholar]

- Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Straus SE. (2009) Does this patient have a pleural effusion? Journal of the American Medical Association 301(3): 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]