Abstract

Background and purpose

Prostate biopsy positivity after radiotherapy (RT) is a significant determinant of eventual biochemical failure. We mapped pre- and post-treatment tumor locations to determine if residual disease is location-dependent.

Materials and methods

There were 303 patients treated on a randomized hypofractionation trial. Of these, 125 underwent prostate biopsy 2-years post-RT. Biopsy cores were mapped to a sextant template, and 86 patients with both pre-/post-treatment systematic sextant biopsies were analyzed.

Results

The pretreatment distribution of positive biopsy cores was not significantly related to prostate region (base, mid, apex; p = 0.723). Whereas all regions post-RT had reduced positive biopsies, the base was reduced to the greatest degree and the apex the least (p = 0.045). In 38 patients who had a positive post-treatment biopsy, there was change in the rate of apical positivity before and after treatment (76 vs. 71%; p = 0.774), while significant reductions were seen in the mid and base.

Conclusion

In our experience, persistence of prostate tumor cells after RT increases going from the base to apex. MRI was used in planning and image guidance was performed daily during treatment, so geographic miss of the apex is unlikely. Nonetheless, the pattern observed suggests that attention to apex dosimetry is a priority.

Keywords: Prostate, Post-treatment, Biopsy, Failure patterns

Prostatic adenocarcinoma is the most common non-skin cancer in males in the United States and is second only to lung cancer in mortality [1]. Both radical prostatectomy (RP) and primary radiotherapy (RT) are effective treatments for localized disease with comparable biochemical failure and survival rates. In the RP setting, positive margins portend biochemical failure [2]. A large percentage of positive margins occur at the apex, which is difficult to identify radiographically and surgically.

In the setting of radiotherapy, the apex is poorly visualized on planning CT [3]. The difficulty in identifying the apex is reflected in high inter-observer variability in delineation [4,5], and it has been suggested that without image guidance prior to treatment up to 17% of patients, particularly those with low-lying apices, are potentially undertreated [6]. MRI much better defines the apex [6], and when used in conjunction with daily image guidance to correct for inter-fraction motion, prostate apical coverage should be improved.

Post-treatment biopsy data from several cohorts of patients treated with external beam radiotherapy indicate that residual prostate cancer cells are seen at 2–3 years after completion of therapy in 20–40% of men clinically without evidence of biochemical or clinical recurrence [7–10]. Two-year positivity is predictive of eventual biochemical failure [11], disease-free survival [12], distant metastasis, and cause-specific survival [13].

The distribution of tumor cells in the prostate after radiotherapy, as seen on post-treatment biopsy, has not been previously examined to our knowledge. We asked whether there is a propensity for persistent disease in the prostate by region. Prostate regions characterized as high-risk for failure based on the pretreatment diagnostic biopsies may benefit from prostate subvolume dose escalation. In this report, we describe the distribution of disease by region as observed in pre- and 2-year post-treatment biopsies for a subset of patients treated on a Phase III randomized trial comparing the efficacy of conventional intensity-modulated radiotherapy (CIMRT) versus hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy (HIMRT) [14].

Material and methods

As previously described [14], 303 assessable patients of 307 patients were accrued to the Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) prostate hypofractionation trial from 2002 to 2006. Mainly patients with intermediate to high-risk prostatic adenocarcinoma were included. High risk per the protocol was defined as Gleason score 8–10, Gleason score 7 in ≥4 cores, cT3 disease, or a PSA >20 ng/mL. Patients were randomized to receive either CIMRT to 76 Gy at 2.0 Gy/fraction or HIMRT to 70.2 Gy at 2.7 Gy/fraction. Details of CT and MRI simulation have been described previously [15]. In particular, the prostate contours at the apex were drawn with both the consideration of the MRI anatomy (including the external sphincter and penile bulb anatomy), as well as CT anatomy, and would be considered generous, especially if apical involvement was seen on prostate diagnostic biopsies or MRI. Patients with high risk disease received long term androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for 2 years. Short term ADT was permitted for up to 4 months in intermediate risk patients.

One hundred and twenty-five patients had post-treatment prostate biopsies per protocol. The biopsy site in the FCCC Prostate Cancer Database was coded by a number, that was connected to the prostate location via a look-up table. A Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) program was utilized to translate the biopsy location to a sextant template, which consisted of a base, mid, and apex for both the left and right sides of the prostate. A patient’s biopsy was included if it had at least 6 cores that were localizable to the sextant template. An insufficient number of cores could occur either because too few cores were sampled at the time of biopsy (uncommon), or if the location descriptors were ambiguous, thus reducing the number of cores localizable to a sextant template below 6. Thus, 36 patients were excluded because of lack of a sufficient number of pre-treatment biopsy cores localizable to a sextant biopsy template. Two patients were excluded because of missing details in biopsy results and one additional patient was excluded because of an insufficient number of post-treatment biopsy sextant-localizable cores, resulting in a total of 86 analyzed patients. There were 86 patients with both pre-(diagnostic) and post-treatment systematic biopsies that could be mapped to a sextant template. Many of the diagnostic biopsies were done at outside institutions, while all the post-treatment biopsies were carried out at FCCC per protocol guidance. All patients had pathologic review and assignment of the Gleason score in the pretreatment prostate biopsies by pathologists at FCCC. Prostate biopsies after radiotherapy naturally fall into four categories: negative, atypical acini suspicious but not diagnostic of carcinoma, adenocarcinoma with treatment effect and adenocarcinoma without treatment effect. The classification of biopsy positivity was based on the presence of residual adenocarcinoma, with or without treatment effect.

Statistical analysis was carried out in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize study patients in terms of age, disease parameters, risk and treatment (use of ADT and radiotherapy treatment arm). Chi-square tests were applied to compare the 86 patients analyzed in this study with those excluded (n = 219).

Biopsy positivity was tabulated by location in pre- and post-treatment samples at the core and patient levels. Chi-square tests were used to compare positivity by region in pre- and post-treatment cores. The rate of biopsy positivity was compared by prostate region using Cochran’s Q statistic for an overall difference and McNemar’s test for pairwise comparisons of regions for both pre- and post-treatment data. Logistic regression was used to assess baseline characteristics, including pre-treatment biopsy positivity of the base, mid or apex regions, and treatment parameters, for association with post-treatment positivity in the apex, and in any region. Multivariable models for each of these outcomes were developed by stepwise selection taking p ≤ 0.10 as entry and retention criteria.

Failure free survival (FFS), defined as the earliest occurrence of PSA failure (nadir + 2 criteria) or clinical evidence of progressive disease or death from any cause, was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by treatment arm using the log rank test.

Results

There were 86 patients who had systematic sextant prostate biopsies and 15 of these developed biochemical or clinical disease failure (BCDF [12 PSA, two salvage ADT and one cryosurgery]) and one died of causes unrelated to prostate cancer. Seventy surviving failure-free patients were followed for a median time of 71.0 months (range 28.1–107.4 months) from the start of RT. Failure-free survival was 86.7% (95% CI: 77.3–92.4%) at 5 years and 76.3% (95% CI: 63.4–85.2%) at 8 years, and did not differ by protocol treatment arm (p = 0.231, log-rank test). Five of the 15 instances of BCDF (4 PSA; 1 salvage ADT) occurred prior to post-treatment biopsy. Thus, 81 patients were considered for analysis of the relationship between post-treatment biopsy findings and subsequent development of BCDF. There was a marginally significant difference in the incidence of subsequent failure among the four biopsy groups (p = 0.082, Gray’s test) with 5-year incidence rates ranging from 5.3% (95% CI: 0.9–15.7%) for patients with normal post-treatment biopsy to 34.4% (95% CI: 2.2–74.1%) for those with atypical cells; 20.6% (95% CI: 5.7–42.0%) for patients with adenocarcinoma showing treatment effect (CA + TE); and 33.3% (95% CI: 3.2–70.4%) for those with frank adenocarcinoma (CA). The significance of these estimates is limited by the small sample size. Similar pathologic designations have been shown to be associated with prostate cancer outcome after radiotherapy in a larger patient cohort [11,16].

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 86 analyzed patients in relation to the 217 trial patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria for this study. Although the post-treatment biopsy cohort patients were evenly allocated to both treatment arms, they were statistically younger and had more favorable baseline characteristics (lower T-category, Gleason score, pre-treatment PSA, and risk) than those in the parent group who did not have post-treatment biopsies. Based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) criteria [17], there were 19 low risk, 56 intermediate risk and 11 high risk patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 86 patients with systematic pre- and post-treatment biopsies in relation to other trial patients.

| Patients with systematic biopsies (86)

|

Others (217)

|

All trial patients (303)

|

p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 45–54 | 10 | 11.9 | 13 | 6.0 | 23 | 7.6 | 0.008 |

| 55–64 | 34 | 39.3 | 56 | 25.8 | 90 | 29.7 | |

| 65–74 | 34 | 40.5 | 103 | 47.5 | 137 | 45.2 | |

| ≥75 | 8 | 8.3 | 45 | 20.7 | 53 | 17.5 | |

| Median (range) | 64 (49–82) | 68 (45–86) | 67 (45–86) | ||||

| T-category | |||||||

| T1 | 30 | 34.9 | 90 | 41.5 | 120 | 39.6 | 0.010 |

| T2 | 52 | 60.5 | 96 | 44.2 | 148 | 48.8 | |

| T3 | 4 | 4.7 | 31 | 14.3 | 35 | 11.6 | |

| Pre-treatment GS | |||||||

| GS 6 | 39 | 45.4 | 65 | 30.0 | 104 | 34.3 | 0.012 |

| GS 7 | 38 | 44.2 | 104 | 47.9 | 142 | 46.9 | |

| GS 8–10 | 9 | 10.5 | 48 | 22.1 | 57 | 18.8 | |

| Pre-treatment PSA | |||||||

| <10 | 62 | 72.1 | 132 | 60.8 | 194 | 64.0 | 0.003 |

| 10–20 | 23 | 26.7 | 58 | 26.7 | 81 | 26.7 | |

| >20 | 1 | 1.2 | 27 | 12.4 | 28 | 9.2 | |

| ADT | |||||||

| Yes | 26 | 30.2 | 113 | 52.1 | 139 | 45.9 | 0.001 |

| No | 60 | 69.8 | 104 | 47.9 | 164 | 54.1 | |

| NCCN risk | |||||||

| Low | 19 | 22.1 | 28 | 12.9 | 47 | 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 56 | 65.1 | 113 | 52.1 | 169 | 55.8 | |

| High | 11 | 12.8 | 76 | 35.0 | 87 | 28.7 | |

| Treatment | |||||||

| Arm I: CIMRT | 44 | 51.2 | 108 | 49.8 | 152 | 50.2 | 0.827 |

| Arm II: HIMRT | 42 | 48.8 | 109 | 50.2 | 151 | 49.8 | |

Abbreviations: GS: Gleason score; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; CIMRT: conventional intensity-modulated radiotherapy; HIMRT: hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

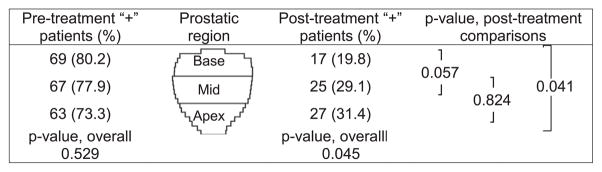

The distribution of positive biopsies was first examined per patient (Fig. 1). Forty-two (48.8%) patients had prostatic adenocarcinoma at diagnosis in all 3 regions (apex, mid and base) and 71 (82.6%) had malignant tissue in at least two prostate regions at diagnosis. Six (7%), two (2.3%) and seven (8.1%) patients had a single positive biopsy in the apex, mid and base, respectively. There was no overall statistical difference (p = 0.529) in the distribution of patients among the prostate regions: 63 (73.3%) patients were positive in the apex, 67 (77.9%) in the mid, and 69 (80.2%) in the base (Fig. 1). In the post-treatment biopsies, 44.2% remained positive by the criteria used and there was a significant difference in the distribution by region overall (p = 0.045). Pairwise tests showed that apex positivity was significantly greater than at the base at 31.4% vs. 19.8% (p = 0.041). Mid-gland positivity (29.1%) was also higher than the base, but not quite significantly so (p = 0.057; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient biopsy positivity by region pre- and post-treatment. Distribution of positive biopsies per prostate region (base, mid and apex) per patient pre- and post-treatment. There is no statistical difference among prostate regions with respect to the proportion of patients with positive pre-treatment findings (p = 0.529, Cochran’s Q test). In post-treatment biopsies, however, there is a significant difference by region (p = 0.045). Pairwise McNemar’s test confirmed that apex positivity is significantly greater than the base: 27 (31.4%) vs. 17 (19.8%), p = 0.041, while mid-gland positivity, 5 (29.1%), is higher than the base by a marginally significant amount (p = 0.057). Rates of positivity in the apex and mid are not significantly different (p = 0.824).

Treatment significantly reduced the percent of patients positive for each prostate region (p < 0.001, Table 2A). Considering the 38 patients with biopsy evidence of disease post-treatment (Table 2B), we found no change in the rate of apex positivity before and after treatment (76.3% vs. 71.1%, p = 0.774), while significant reductions were found in both mid region positivity (89.5% vs. 65.8%, p = 0.049) and base positivity (81.6% vs. 44.7%, p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Change in biopsy positivity, pre- versus post-treatment, by prostate region.

| Apex

|

Mid

|

Base

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| (A) 86 patients with assessable pre- and post-treatment biopsies | ||||||

| Stable Negative (−, −) | 18 | 20.9 | 15 | 17.4 | 15 | 17.4 |

| Eradicated (+,−) | 41 | 47.7 | 46 | 53.5 | 54 | 62.8 |

| New Positive(−,+) | 5 | 5.8 | 4 | 4.7 | 2 | 2.3 |

| Persistent Positive (+,+) | 22 | 25.6 | 21 | 24.4 | 15 | 17.4 |

| Pre-treatment + | 63 | 73.3 | 67 | 77.9 | 69 | 80.2 |

| Post-treatment + | 27 | 31.4 | 25 | 29.1 | 17 | 19.8 |

| Change | −41.9 | −48.8 | −60.4 | |||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| (B) 38 patients with post treatment biopsy failure | ||||||

| Stable Negative (−, −) | 4 | 10.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 13.2 |

| Eradicated (+,−) | 7 | 18.4 | 13 | 34.2 | 16 | 42.1 |

| New Positive (−,+) | 5 | 13.2 | 4 | 10.5 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Persistent Positive (+,+) | 22 | 57.9 | 21 | 55.3 | 15 | 39.5 |

| Pre-treatment + | 29 | 76.3 | 34 | 89.5 | 31 | 81.6 |

| Post-treatment+ | 27 | 71.1 | 25 | 65.8 | 17 | 44.7 |

| Change | −5.2 | −23.7 | −36.9 | |||

| p-Value | 0.774 | 0.049 | 0.001 | |||

Stable Neg (−, −): negative pre-and post-treatment biopsies.

Eradicated (+,−): positive pre- and negative post-treatment biopsies.

New Pos (−,+): negative pre- and positive post-treatment biopsies.

Persistent Pos (+,+): positive pre- and post-treatment biopsies.

Univariate logistic regression was then performed using post-treatment biopsy positivity in any prostate region (yes vs. no) as the endpoint (Table 3A, center column). Of the clinical and dosimetric factors tested, T-category, percent positive tissue (PPT), pre-treatment positivity in the mid region and use of ADT (any use) were identified as factors associated with biopsy positivity. All these factors except mid region positivity remained significant in multivariable analysis (Table 3B). Risk of biopsy positivity increased approximately threefold with advanced T-category (OR = 2.7; 95% CI: 1.0–7.7, p = 0.054) and fourfold if PPT was more than 20% (OR = 3.9; 95% CI: 1.4–10.9, p = 0.011). In contrast, use of neoadjuvant/adjuvant ADT reduced the risk by 80% (OR = 0.2; 95% CI: 0.1–0.7, p = 0.008).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of clinical and dosimetric characteristics with respect to post-treatment biopsy positivity as the endpoint. Significant Odds Ratios (p-Value < 0.05) are shown in bold.

| Characteristic | Any region “+”

|

Apex “+”

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | |

| (A) Univariate models | ||||

| Age ≥ 65 vs. ≤ 64 | 1.3 | 0.531 | 0.6 | 0.311 |

| T2a–T3c vs. T1 | 2.5 | 0.056 | 4.5 | 0.012 |

| GS ≥7 vs. ≤ 6 | 1.0 | 0.919 | 1.3 | 0.562 |

| PSA ≥10 vs. < 10 | 1.1 | 0.848 | 1.1 | 0.810 |

| NCCN intermediate vs. low risk | 1.0 | 0.943 | 0.7 | 0.601 |

| NCCN high vs. low risk | 0.4 | 0.285 | 0.6 | 0.593 |

| ADT yes vs. noa | 0.3 | 0.038 | 0.7 | 0.557 |

| PPT > 20 vs. ≤ 20% | 3.4 | 0.010 | 4.7 | 0.002 |

| GS 4–5 > 4 vs. ≤ 4%b | 1.5 | 0.386 | 2.0 | 0.197 |

| HIMRT vs. CIMRT | 0.6 | 0.268 | 0.6 | 0.311 |

| Prostate volume > 54 vs. ≤ 54 ccc | 0.7 | 0.499 | 0.8 | 0.582 |

| Prostate volume > 70 vs. ≤ 70 ccb | 1.0 | 0.933 | 1.2 | 0.692 |

| Prostate BED min > 110 vs. ≤ 110 Gyc | 0.8 | 0.564 | 1.4 | 0.469 |

| Prostate BED min > 115 vs. ≤ 115 Gyb | 1.1 | 0.890 | 1.8 | 0.268 |

| Prostate BED mean > 142 vs. ≤ 142 Gyc | 0.6 | 0.290 | 0.5 | 0.193 |

| Prostate BED mean > 147 vs. ≤ 147 Gyb | 0.5 | 0.215 | 0.5 | 0.277 |

| Prostate BED max > 162 vs. ≤ 162 Gyc | 0.7 | 0.335 | 0.5 | 0.154 |

| Prostate BED max > 169 vs. ≤ 169 Gyb | 0.8 | 0.569 | 0.5 | 0.248 |

| Pre-treatment base “+” vs. “−” | 1.2 | 0.780 | 1.1 | 0.844 |

| Pre-treatment mid “+” vs. “−” | 3.9 | 0.028 | 11.4 | 0.021 |

| Pre-treatment apex “+” vs. “−” | 1.3 | 0.569 | 1.9 | 0.248 |

| (B) Multivariable models | ||||

| T2a–T3c vs. T1 | 2.7 (1.0–7.7) | 0.054 | 3.9 (1.2–13.3) | 0.029 |

| PPT > 20% vs. ≤ 20% | 3.9 (1.4–10.9) | 0.011 | 4.2 (1.5–11.4) | 0.006 |

| ADT yes vs. no | 0.2 (0.1–0.7) | 0.008 | – | – |

Abbreviations: OR: Odds ratio; GS: Gleason score; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; PPT: percent positive tissue; CIMRT: conventional intensity-modulated radiotherapy; HIMRT: hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy; BED: biologically equivalent dose.

Grouping high risk long term ADT and intermediate risk short term ADT users together vs. favorable and intermediate risk patients who did not receive ADT.

75th percentile cutpoint.

Median cutpoint.

With respect to apex positivity on post-treatment biopsies (Table 3A, right column), univariate logistic regression identified higher T-category (2a–3c), more than 20% positive diagnostic tissue (PPT), and pre-treatment positivity in the mid region as risk factors. The reason for the association of mid region pre-treatment positivity to post-treatment apex positivity is unclear, but we hypothesize that assignment of mid vs apex in the diagnostic (outside) biopsies might be subject to more variability than assignments of post-treatment biopsies done under protocol guidelines. No association was found with a number of other factors examined including the Gleason score, pre-treatment PSA, risk group, protocol treatment arm, prostate volume, dosimetric parameters or pretreatment positivity in the apex or in the base. On multivariable analysis with respect to apex positivity (Table 3B), only advanced T-category and pre-treatment biopsy tissue with more than 20% tumor involvement remained significant with both factors increasing risk approximately fourfold.

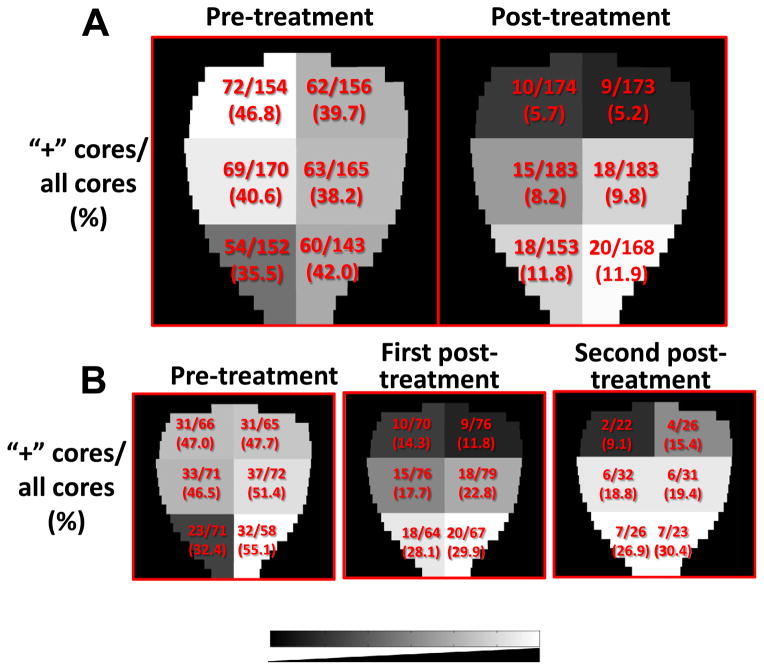

We then examined the overall distribution of positive biopsies pre- and post-treatment, unadjusted by patient. Fig. 2A displays the findings, with regions containing higher percentages of positive biopsies represented in lighter shades. Looking at biopsy positivity and negativity in the apex, mid and base prostate regions, combining left and right sides, we obtain a 3 × 2 contingency table. No significant difference was found among the three regions with respect to the number of positive cores in the pre-treatment biopsy analysis (p = 0.46). In contrast, a similar analysis of the 2-year post-treatment biopsies yielded a significant alteration in the distribution going from lowest in the base to highest in the apex (p = 0.014).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of positive cores represented on a gray scale. (A) Proportion of pre-treatment and 2-year post-treatment positive cores by region for the entire cohort (n = 86). (B) Pre-treatment (left) and 2-year post-treatment (center) core counts for the 38 study patients with positive post-treatment biopsies, and repeat post-treatment core counts for the subset of 14 patients who received a post-treatment biopsy beyond 2 years (right). The gray scale represents lower (darker) to higher (lighter) percentage of positive biopsies.

A similar relationship was seen in the overall biopsy positivity percentages by region for the 38 patients who had a positive biopsy 2 years post-treatment (Fig. 2B). In this subgroup, there was no significant difference in regional positivity before treatment (Fig. 2B left p = 0.56), but a significant increase was noted going from base to apex post-treatment (Fig. 2B center, p = 0.005). There were 14 individuals who went on to obtain a second repeat biopsy at a median of 3.2 years, ranging from 2.9 to 3.9 years from completion of all therapy (including ADT). All of these patients were without a rising PSA for both biopsies and only one had frank adenocarcinoma (without treatment effect) on the first post-treatment biopsy. On the second post-treatment biopsy, two converted to negative. The pattern of increasing biopsy positivity going from base to apex persisted; but, these differences were not significant due to small numbers.

Since there was a trend for post-treatment biopsy positivity increasing from base to apex, the apex (inferior third portion of the prostate) patient target volume (PTV) coverage was examined for 21 (11 CIMRT and 10 HIMRT) randomly selected patients from the clinical trial. The mean doses to the apex and prostate remainder PTVs, including standard deviation, were 78.68 ± 2.98 Gy and 78.86 ± 2.81 Gy, respectively (p = 0.836, Student’s T-test). However, the D95% for the apex PTV was lower at 73.1 Gy as compared to 74.2 Gy for the reminder PTV (p = 0.017).

Discussion

The aim of this analysis was to determine whether there was a regional pattern of prostate biopsy positivity after radiotherapy. Post-treatment biopsy positivity in the FCCC hypofractionation trial waspredictive of biochemical failure later [16]. Inother studies, such as the MDACC randomized dose escalation study, post-treatment biopsy positivity was the strongest predictor of eventual biochemical failure [11], with a roughly 50% risk of eventual biochemical failure 8–10 years later. Although slightly differing criteria have been used to define a positive biopsy in some other notable series [12], the significance of post-treatment tumor remains incontrovertible.

Our results show a shift from comparable rates of positivity in patients by sextant region in pre-treatment diagnostic biopsy cores to a significant difference in post-treatment rates with the highest proportion observed in the apex. Data also indicate that the best rates of tumor eradication were at the base, with a distinct trend of increasing rates of positivity – both new positive and persistent positive – from the base to apex.

Despite careful attention to the apex in planning and adjustment for interfraction motion, treatment was relatively less efficacious at tumor eradication in the apex. There was a 41.9% reduction from pre- to post-treatment biopsy positivity for apex disease compared to a 48.8% decrease in mid positivity and a 60.4% decrease in base positivity. This difference was more pronounced among the 38 patients with any positive post-treatment biopsy (Table 2), with apex positivity rates reduced by 5.2% compared to 23.7% in the mid and 36.9% in the base.

These findings, together with the observations in other studies that post-treatment biopsy positivity is strongly associated with biochemical failure [11] and survival [12], imply that residual disease in the apex may be preferentially responsible for progression. The mechanism of this redistribution toward the apex is unclear but could be related to apical contouring, dosimetry, unaccounted for uncertainties (e.g., MRI-CT fusion for planning and intrafraction motion), systematic errors in adjustment for interfraction motion, or radioresistence due to hypoxia or tumor-stromal reactions.

The FCCC hypofractionation trial included a number of procedural components that are pertinent to the potential mechanisms considered. MRI was fused to the planning CT to better define the apex, rectal prostate interface, bladder prostate interface and the penile bulb. Margins were relatively generous at the apex at 8 mm for the standard fractionation arm and 7 mm for the hypofractionation arm. Of note, the D95% PTV coverage of the prostate was 100%, as described previously [15]. Mean doses at the apex (lower third of the prostate) were similar; however, the D95% was slightly lower. Whether this difference is clinically meaningful is unclear. In addition, trans-abdominal ultrasound was used to localize the prostate daily to correct for interfraction motion. Although it is possible that there was a systematic error related to the use of ultrasound since the greatest error is in the superior–inferior axis, the team at FCCC has the longest experience with ultrasound in this context and the correlation with CT has been demonstrated previously to be very high [18–21]. Of note, radiation treatment was observed to be effective at reducing disease within all regions of the prostate and the mid-gland was consistently intermediate, which is also consistent with an increasing resistance mechanism from superior to inferior, as opposed to a geographic miss.

The patients selected for this study were significantly younger and had more favorable baseline characteristics (lower T-stage, Gleason score, pre-treatment PSA, and risk group) than those excluded. The finding of apical disease persistence presented here nonetheless remains relevant in the era of PSA screening and stage migration. In this selected patient group, T-category and PPT were the only clinical-pathologic factors associated with post treatment biopsy failure, both overall and apical. Furthermore, the data suggest that whereas ADT reduced the risk of biopsy positivity overall, there was less of an effect at the apex.

In summary, the distributions of positive biopsies between the diagnostic and 2 year post-treatment biopsies shifted from no regional difference to a gradient of greater positivity in the mid and apical regions than in the base post treatment. While the mechanism is unclear, this finding is cautionary. Contouring should be generous, and dosimetry around the apical region and the potential for systematic errors in adjusting for interfraction motion considered. In addition, because of the lack of a capsule in this part of the prostate, tumor may be more inferior than realized, even if the diagnostic biopsies are designated as being positive in the mid-gland and not the apex. More generous contouring around the apex comes with its own problems, such as increasing dose to the penile bulb and a risk of erectile dysfunction. The tumor location relationships in post-treatment biopsies reported need to be further established as well as how best to improve tumor eradication in prostate regions at a higher risk of persistent disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants CA-006927 and CA101984-01 from the National Cancer Institute, and Grant 09-BW-11 from Bankhead Coley Cancer Research Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastham JA, Kuroiwa K, Ohori M, et al. Prognostic significance of location of positive margins in radical prostatectomy specimens. Urology. 2007;70:965–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin PW, Evans C, Feng M, et al. Radiographic and anatomic basis for prostate contouring errors and methods to improve prostate contouring accuracy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasch C, Barillot I, Remeijer P, et al. Definition of the prostate in CT and MRI: a multi-observer study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Brabandere M, Hoskin P, Haustermans K, Van den Heuvel F, Siebert F-A. Prostate post-implant dosimetry: interobserver variability in seed localization, contouring and fusion. Radiother Oncol. 2012;104:192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milosevic M, Voruganti S, Blend R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for localization of the prostatic apex: comparison to computed tomography (CT) and urethrography. Radiother Oncol. 1998;47:277–84. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levegrün S, Jackson A, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Risk group dependence of dose-response for biopsy outcome after three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy of prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2002;63:11–26. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack A, Zagars GK, Antolak JA, et al. Prostate biopsy status and PSA nadir level as early surrogates for treatment failure: analysis of a prostate cancer randomized radiation dose escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:677–85. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02977-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sathya JR. Randomized trial comparing iridium implant plus external-beam radiation therapy with external-beam radiation therapy alone in node-negative locally advanced cancer of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1192–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CU, Hunt D, McGowan DG, et al. Radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:107–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vance W, Tucker SL, De Crevoisier R, Kuban DA, Cheung MR. The predictive value of 2-year posttreatment biopsy after prostate cancer radiotherapy for eventual biochemical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:828–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crook JM, Malone S, Perry G, et al. Twenty-four-month postradiation prostate biopsies are strongly predictive of 7-year disease-free survival: results from a Canadian randomized trial. Cancer. 2009;115:673–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelefsky MJ, Yamada Y, Fuks Z, et al. Long-term results of conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: impact of dose escalation on biochemical tumor control and distant metastases-free survival outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1028–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollack A, Walker G, Horwitz EM. A randomized trial of hypofractionated external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Onc. 2013;31:3860–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack A, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM. Dosimetry and preliminary acute toxicity in the first 100 men treated for prostate cancer on a randomized hypofractionation dose escalation trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:518–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoyanova R, Walker G, Sandler K. Determinants of prostate biopsy positivity 2 years after radiation therapy for men with prostate cancer treated on a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:S60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feigenberg SJ, Paskalev K, McNeeley S, et al. Comparing computed tomography localization with daily ultrasound during image-guided radiation therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer: a prospective evaluation. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2007;8:2268. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v8i3.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lattanzi J, McNeeley S, Hanlon A, et al. Ultrasound-based stereotactic guidance of precision conformal external beam radiation therapy in clinically localized prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;55:73–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lattanzi J, McNeeley S, Donnelly S, et al. Ultrasound-based stereotactic guidance in prostate cancer—quantification of organ motion and set-up errors in external beam radiation therapy. Comput Aided Surg. 2000;5:289–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-0150(2000)5:4<289::AID-IGS7>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lattanzi J, McNeeley S, Pinover W, et al. A comparison of daily CT localization to a daily ultrasound-based system in prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:719–25. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]