Abstract

Introduction:

Clindamycin is an excellent drug for skin and soft tissue Staphylococcus aureus infections, but resistance mediated by inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (iMLSB) phenotype leads to in vivo therapeutic failure even though they may be in vitro susceptible in Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method.

Objective:

The study was aimed to detect the prevalence of iMLSB phenotype among S. aureus isolates by double disk approximation test (D-test) in a tertiary care hospital, Eastern India.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 209 consecutive S. aureus isolates were identified by conventional methods and subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing by Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method. Erythromycin-resistant isolates were tested for D-test.

Results:

From 1282 clinical specimens, 209 nonrepeated S. aureus isolates were obtained. Majority of isolates 129 (61.7%) were methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). There was statistically significant difference between outpatients 60.1% and inpatients 39.9% (P < 0.0001). From 209 S. aureus isolates, 46 (22%) were D-test positive (iMLSB phenotype), 41 (19.6%) were D-test negative (methicillin sensitive [MS] phenotype), and 37 (17.7%) were constitutively resistant (constitutive macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B phenotype). The incidence of inducible, constitutive, and MS phenotype was higher in MRSA isolates compared to MS S. aureus (MSSA). The constitutive clindamycin resistance difference between MSSA and MRSA isolates were found to be statistically significant (P = 0.0086).

Conclusion:

The study revealed 22% of S. aureus isolates were inducible clindamycin resistant, which could be easily misidentified as clindamycin susceptible in Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method. Therefore, clinical microbiology laboratory should routinely perform D-test in all clinically isolated S. aureus to guide clinicians for the appropriate use of clindamycin.

Keywords: Constitutive macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B phenotype, D-test, inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B phenotype, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, sensitive methicillin phenotype, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus aureus

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common Gram-positive pyogenic bacteria responsible for variety of diseases that range in severity from mild skin soft tissue infections to life-threatening conditions such as endocarditis, pneumonia, and sepsis.[1] In the scenario of increasing methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections, the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) group of antibiotics which are structurally different with a same mechanism of action serves as one good alternative.[2] These antibiotics inhibit bacterial protein synthesis in susceptible organisms by reversibly binding to the 23 S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) receptor 50 S ribosomal subunit.[3] Among these, clindamycin is the preferred agent due to its excellent pharmacokinetic properties, available in both intravenous and oral formulations with 90% oral bioavailability, less costly, good tissue penetration, and accumulation in deep abscesses, not impeded by high bacterial burden at infection sites and may be able to inhibit production of certain toxins and virulence factors in Staphylococci.[4,5] However, indiscriminate use of MLSB group of antibiotics has led to an increase in resistance among Staphylococcal isolates.[6]

The MLSB resistant phenotype in S. aureus can be either constitutive MLSB (cMLSB) or inducible MLSB (iMLSB). Staphylococci that express ribosomal methylases (erm) genes may exhibit in vitro resistance to erythromycin, clindamycin, and other drugs of MLSB group. This resistance is referred to as the cMLSB phenotype. However, in some Staphylococci, those express erm genes require an inducing agent to synthesize methylase for clindamycin resistance. This type of is referred to as iMLSB phenotype. These organisms are resistant to erythromycin and falsely susceptible to clindamycin in vitro.[7] This type of inducible clindamycin resistance cannot be detected by standard Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method, broth micro dilution testing, automated susceptibility testing devices, or Epsilometer test.[8] Thus, falsely susceptible clindamycin will lose its effectiveness in vivo and thereby increase the chance of therapeutic failures.[9]

The double disk approximation test (D-test) that involves the placement of an erythromycin disk in proximity to the disk containing clindamycin. As the erythromycin diffuses through the agar, the resistance to the clindamycin is induced, resulting in a flattening or blunting of the clindamycin zone of inhibition adjacent to the erythromycin disk, giving a “S” shape to the zone. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommends D-test, which is a phenotypic screening method for inducible clindamycin resistance.[10] Therefore, all erythromycin resistant S. aureus should be tested for inducible clindamycin resistance to prevent clindamycin treatment failures and to report prevalence resistant phenotypes which varies widely. The present study was aimed to determine the constitutive and inducible clindamycin resistance in S. aureus isolated from various clinical specimens at a tertiary care hospital in Odisha state, Eastern India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, sample collection, and identification of Staphylococcus aureus

The prospective study was carried out from September 2013 to August 2014 in the Department of Microbiology at a Tertiary Care Hospital, Odisha state, Eastern India. A total of 1282 clinical specimens were collected, i.e., pus and wound swab, blood, urine, sputum, aspirates, and body fluids from patients with active infections. These specimens were collected from both hospitalized, i.e., surgical, medical, and Intensive Care Units and outpatients. From 1282 clinical specimens, 209 consecutive, nonrepeat S. aureus isolates were obtained. These isolates were confirmed as S. aureus isolates by conventional catalase, tube and slide coagulase, and DNAse test.[11] Patients from whom S. aureus was isolated in the absence of clinical disease suggesting colonization were not included in this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All S. aureus isolates were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing using Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates. Methicillin resistance was determined by disk diffusion method using 30 μg cefoxitin disks. The results were interpreted according to CLSI guidelines. The quality control of erythromycin, clindamycin, and cefoxitin disks were performed with S. aureus ATCC 25923 strains. All culture media, antibiotic disks, biochemical reagents, and control strains were procured from Hi Media Labs. Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Double disk approximation test (D-test)

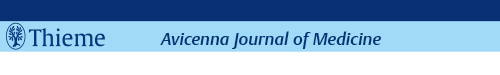

The isolates that were resistant to erythromycin were tested for inducible clindamycin resistance by double disk approximation test (D-test) as per CLSI guidelines. In this test, a 0.5 McFarland's standard suspension of S. aureus was prepared and plated onto MHA plate. An erythromycin disk (15 μg) and clindamycin (2 μg) were placed 15 mm apart edge-to-edge on MHA plate.[12] Plates were analyzed after 18 h of incubation at 35°C. Interpretation of zone of inhibition is indicated in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Interpretation of zones of inhibition and D-test results in Staphylococcus aureus

Different phenotypes were detected when erythromycin (15 μg) and clindamycin (2 μg) disks were placed next to each other in MHA plates.

They were interpreted as follows:

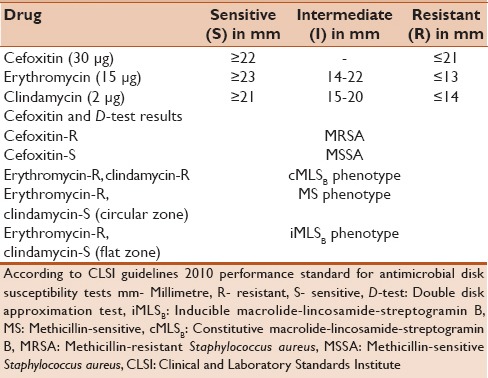

Methicillin-sensitive (MS) phenotype: Isolates resistant to erythromycin but sensitive to with a circular zone of inhibition around clindamycin (D-test negative). The organism is interpreted as clindamycin sensitive [Figure 1]

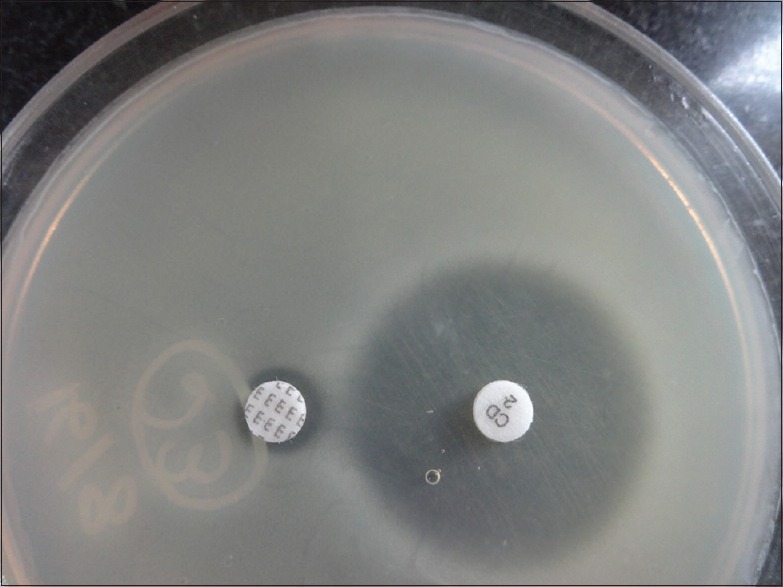

iMLSB phenotype: Isolates resistant to erythromycin but sensitive to clindamycin showing flattening of the zone of inhibition around clindamycin producing a “D” shaped blunting toward erythromycin disk (D-test positive). The organism is interpreted as clindamycin resistant [Figure 2]

cMLSB phenotype: Isolates resistant to both erythromycin and clindamycin with no or small zone of inhibition around clindamycin.

Figure 1.

Methicillin-sensitive phenotype (D-test negative)

Figure 2.

Inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B phenotype (D-test positive)

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Inc. statistical software (2236 Avenida de la Playa La Jolla, CA 92037, USA) was used for calculation of P value using Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was defined when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

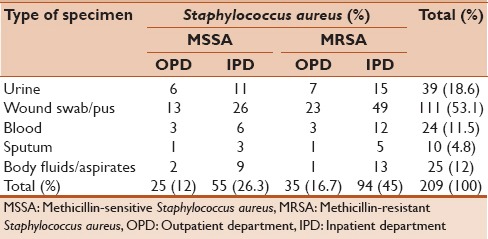

A total of 209 nonrepeated S. aureus isolates were obtained from 1282 clinical specimens such as pus and wound swabs, blood, urine, sputum, aspirates, and body fluids which were collected from 770 (60.1%) outpatients and 512 (39.9%) hospitalized patients. Maximum S. aureus isolates were detected from pus and wound swabs 53.1%, followed by urine 18.6%, aspirates 12%, and blood 11.5%. From 209 S. aureus isolates, 129 (61.7%) were MRSA and rest 80 (39.3%) were MS S. aureus (MSSA). Highest number of MRSA was detected from pus and wound swabs 34.4%, followed by urine 10.5% [Table 2]. Majority of S. aureus isolates 149 (71.3%) were obtained from hospitalized patients and rest 60 (28.7%) were from outpatients. There was statistically significant difference in S. aureus, and MRSA isolates obtained between outpatients and hospitalized patients (P < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Distribution of clinical specimens according to their origin and methicillin susceptibility

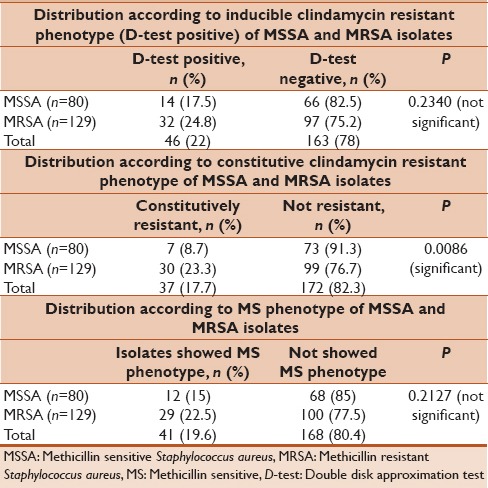

All 209 S. aureus isolates were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. One hundred twenty-four (59.3%) were found to be resistant to erythromycin. The resistant erythromycin isolates were tested for D-test. The result of the D-test revealed that 37 (7 MSSA, 30 MRSA) isolates were resistant to both erythromycin and clindamycin indicating cMLSB phenotype. Forty-one (12 MSSA, 29 MRSA) isolates were D-test negative, indicating MS phenotype. These isolates were truly susceptible to clindamycin. Rest 46 (14 MSSA, 32 MRSA) isolates were D-test positive, indicating iMLSB phenotype [Table 3]. These isolates were actually resistant to clindamycin which would have been easily missed and reported as clindamycin susceptible in regular Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility testing. The study also showed that higher percentage MRSA isolates were both constitutive and inducible clindamycin resistant in comparison to MSSA.

Table 3.

Results of the D-test

DISCUSSION

Antimicrobial resistance in S. aureus has become an ever-increasing problem among both outpatients and inpatients of health care facilities. Clindamycin, a lincosamide, has always been an attractive opinion for MSSA and MRSA skin and soft tissue infections. It is available in oral and parenteral formulations, 90% oral bioavailability, less costly in comparison to newer drugs, good tissue penetration and may be able to inhibit production of certain toxins and virulence factors in Staphylococci.[4,5] However, resistance to clindamycin is highly variable, and incidence of its resistant phenotypes varies by geographic regions and even between hospitals.[13] These isolates have a high rate of spontaneous mutation during the therapeutic process which would enable them to develop resistance to clindamycin.[14] Thus, the empirical treatment options against S. aureus infections have become more limited. Few studies have been performed that report the presence of both constitutive and inducible clindamycin resistance in Eastern India. Therefore, this study was undertaken to detect and report the presence of clindamycin-resistant phenotypes in a tertiary care hospital, Eastern India.

The prevalence of MRSA isolates among S. aureus was high (61.7%) in this study, which is similar to Sah et al. (61.4%), Mansouri and Sadeghi (56.8%), and Chudasama et al. (54.78%).[15,16,17] Lyall et al. had reported a very high percentage of MRSA (91.5%) in their study.[18] Between the mid-1970s and late-1990s, MRSA was considered a healthcare system-associated pathogen resistant to multiple drug classes in addition to β-lactam resistance. However, the emergence of community-associated MRSA in the past years among patients without obvious risk factors has shifted the management of Staphylococcal infections from various β-lactam first line antibiotics to MLS group of antibiotics.

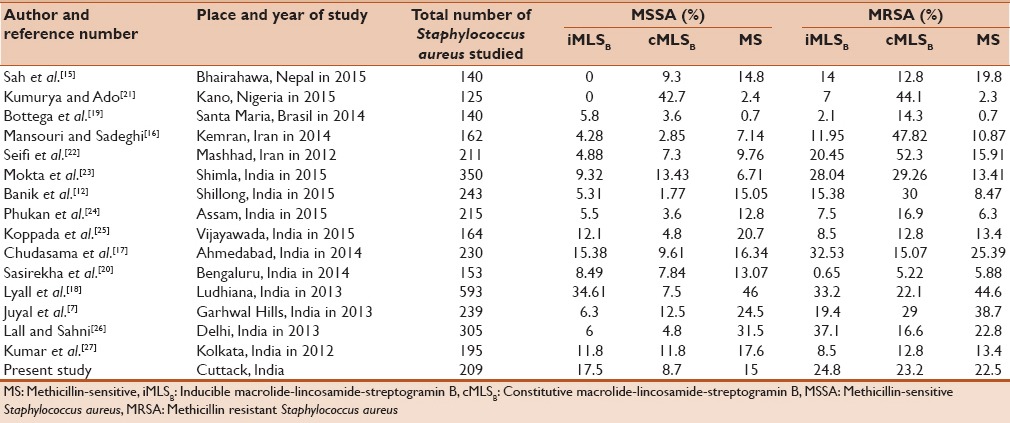

In our study from 209 S. aureus, 124 (59.3%) isolates were resistant to erythromycin. All erythromycin resistants were subjected to D-test. A positive D-test indicates that there is existence of inducible clindamycin resistant phenotype. Our study revealed 46 (22%) of S. aureus isolates were D-test positive. In different studies, the inducible clindamycin ranged from 0% to 37.1% [Table 4].[7,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] It was observed that percentage of inducible clindamycin resistance was higher among MRSA (24.8%) compared to MSSA (7.5%). The difference between MSSA and MRSA isolates were not statistically significant (P = 0.2340). Most of the authors have reported higher inducible clindamycin-resistant isolates in MRSA compared to MSSA [Table 4]. On the contrary, Bottega et al. and Sasirekha et al. had shown a higher percentage of inducible resistance in MSSA compared to MRSA.[19,20] The different patterns of resistance observed in various studies are due to resistance varies by geographical regions, age groups, antibiotic prescription patterns, methicillin susceptibility, and even from hospital to hospital. This type of inducible clindamycin resistance can only be detected phenotypically by placing erythromycin and clindamycin disk adjacent to each other in MHA plate by disk diffusion method. Therefore, the D-test can minimize clindamycin treatment failures.

Table 4.

Distribution of inducible, constitutive and MS clindamycin resistant phenotypes in Staphylococcus aureus from various studies across the globe

Constitutive clindamycin resistance in our study was observed in 7 (8.7%) of MSSA and 30 (23.3%) of MRSA isolates, which is similar to Chudasama et al.[17] The constitutive clindamycin resistance difference between MSSA and MRSA isolates were found to be statistically significant (P = 0.0086). In different studies, the constitutive clindamycin resistance was reported varies from 1.77% to 52.3% [Table 4].[7,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

Truly clindamycin-sensitive isolates, which exhibit MS phenotype, were present in 15% of MSSA and 22.5% of MRSA isolates in our study. This result is in close agreement with Sah et al.[15] In different studies, authors have reported the MS phenotype varies between 0.7% and 44.6% [Table 4].[7,12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] This result implies that clindamycin can be safely and effectively instituted as a therapeutic option in this group of patients even in the presence of macrolide resistance.

CONCLUSION

Due to the emergence of resistance to antimicrobial agents among S. aureus, accurate antimicrobial susceptibility data is an essential factor in making appropriate therapeutic decisions. Overall, the inducible clindamycin-resistant isolates obtained in our study were 22%. If D-test would not have been performed, nearly one-fourth of inducible clindamycin resistant S. aureus could have been easily misidentified as clindamycin susceptible leading to therapeutic failure. Thus, simple and reliable D-test can be incorporated into routine Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method in clinical microbiology laboratory. This enables the clinicians in judicious use of clindamycin, as clindamycin is not a suitable drug for D-test positive S. aureus isolates. Therefore, the clindamycin treatment failure could be minimized.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dong J, Qiu J, Wang J, Li H, Dai X, Zhang Y, et al. Apigenin alleviates the symptoms of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia by inhibiting the production of alpha-hemolysin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013;338:124–31. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lertcanawanichakul M, Chawawisit K, Choopan A, Nakbud K, Dawveerakul K. Incidence of constitutive and inducible clindamycin resistance in clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Walailak J Sci Technol. 2007;4:155–63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciraj AM, Vinod P, Sreejith G, Rajani K. Inducible clindamycin resistance among clinical isolates of staphylococci. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:49–51. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens DL, Gibbons AE, Bergstrom R, Winn V. The eagle effect revisited: Efficacy of clindamycin, erythromycin, and penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal myositis. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:23–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyle EA, Lewis RL, Prince RA. Influence of clindamycin on the release of Staphylococcus aureus α haemolysin from methicillin resistant S. aureus: Could MIC make a difference [abstract 182]? Crit Care Med. 2003;31(Suppl 1):A48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saiman L, O‘Keefe M, Graham PL, 3rd, Wu F, Saïd-Salim B, Kreiswirth B, et al. Hospital transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among postpartum women. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1313–9. doi: 10.1086/379022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juyal D, Shamanth AS, Pal S, Sharma MK, Prakash R, Sharma N. The prevalence of inducible clindamycin resistance among staphylococci in a tertiary care hospital – A study from the Garhwal hills of Uttarakhand, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:61–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4877.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorgensen JH, Crawford SA, McElmeel ML, Fiebelkorn KR. Detection of inducible clindamycin resistance of staphylococci in conjunction with performance of automated broth susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1800–2. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1800-1802.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel M, Waites KB, Moser SA, Cloud GA, Hoesley CJ. Prevalence of inducible clindamycin resistance among community- and hospital-associated Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2481–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02582-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2013. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twenty-second Informational Supplement Document M100-S22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baird P. Staphylococcus: Cluster-forming gram positive cocci. In: Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marmion BP, Simmons A, editors. Mackie and McCartney Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banik A, Khyriem AB, Gurung J, Lyngdoh VW. Inducible and constitutive clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus in a Northeastern Indian tertiary care hospital. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:725–31. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiebelkorn KR, Crawford SA, McElmeel ML, Jorgensen JH. Practical disk diffusion method for detection of inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4740–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4740-4744.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabhu K, Rao S, Rao V. Inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples. J Lab Physicians. 2011;3:25–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.78558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sah P, Khanal R, Lamichhane P, Upadhaya S, Lamsal A, Pahwa VK. Inducible and constitutive clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: An experience from Western Nepal. Int J Biomed Res. 2015;6:316–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansouri S, Sadeghi J. Inducible clindamycin resistance in methicillin-resistant and-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolated from South East of Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2014;7:e11868. doi: 10.5812/jjm.11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chudasama V, Solanki H, Vadsmiya M, Vegad MM. Prevalence of inducible clindamycin resistance of Staphylococcus aureus from various clinical specimens by D test in tertiary care hospital. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyall KD, Gupta V, Chhina D. Inducible clindamycin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Mahatma Gandhi Inst Med Sci. 2013;18:112–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottega A, Rodrigues Mde A, Carvalho FA, Wagner TF, Leal IA, Santos SO, et al. Evaluation of constitutive and inducible resistance to clindamycin in clinical samples of Staphylococcus aureus from a tertiary hospital. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:589–92. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0140-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasirekha B, Usha MS, Amruta JA, Ankit S, Brinda N, Divya R. Incidence of constitutive and inducible clindamycin among hospital-associated Staphylococcus aureus. Biotech. 2014;4:85–9. doi: 10.1007/s13205-013-0133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumurya AS, Ado ZG. Detection of clindamycin resistance among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in Kano, Nigeria. Access J Microbiol. 2015;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seifi N, Kahani N, Askari E, Mahdipour S, Naderi NM. Inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from Mashhad, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2012;4:82–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mokta KK, Verma S, Chauhan D, Ganju SA, Singh D, Kanga A, et al. Inducible clindamycin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from sub Himalayan Region of India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:DC20–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13846.6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phukan C, Ahmed GU, Sarma PP. Inducible clindamycin resistance among Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a tertiary care hospital of Assam. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:456–8. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.158603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppada R, Meeniga S, Anke G. Inducible clindamycin resistance among in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from various clinical samples with special reference to MRSA. Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2015;3:2374–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lall M, Sahni AK. Prevalence of inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples. Med J Armed Forces India. 2014;70:43–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Bandyopadhyay M, Bhattacharya K, Bandyopadhyay MK, Banerjee P, Pal N, et al. Inducible clindamycin resistance in Staphylococcus isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Eastern India. Ann Trop Public Health. 2012;5:468–70. [Google Scholar]