Abstract

Introduction:

The construction industry, which mainly consists of migrant labouers is one of the largest employers in the unorganized sector in India. These workers work in poor conditions and are often vulnerable to exploitation. These workers also do not have health care benefits and often these factors lead to poor quality of life (QOL) and psychological distress.

Objectives:

To assess the QOL, probable psychological distress and associated factors among male construction workers.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2013 and November 2013 among 404 male workers. These construction workers were enrolled by consecutive sampling at a construction area in Kolar district, Kaarnataka, India. The study tools used were World Health Organization (WHO) QOL-BREF and 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) to assess QOL and probable psychological distress, respectively. The transformed scores in WHO QOL-BREF in all four domains ranged 0–100. The four domain scores are scaled in a positive direction with higher scores indicating a higher QOL. Associations were done using statistical tests such as Chi-square, correlation, regression, independent samples t-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Results:

A total of 404 male workers with a mean age of 25.6 ± 7.3 years were studied. Mean scores of various domains of QOL were 68.5 ± 13.7 (physical), 59.9 ± 13.5 (psychological), 64.3 ± 16.4 (social), and 44.1 ± 12.8 (environmental). On the self- rating scale, 59 (14.6%) workers were rated as having poor QOL. The prevalence of probable psychological distress was 27.5%. Factors such as increasing age, being currently married, and low educational status were found to be significantly associated (P < 0.05) with poor QOL and psychological distress. There was a significant negative correlation (P < 0.05) between QOL and psychological distress and a positive correlation between income and QOL.

Conclusion:

The QOL in the environmental domain, which mainly deals with living conditions, health, and recreational facilities was found to be poor and there was a high prevalence of probable psychological distress among workers. This indicates a need for improving workplace amenities, and access to health and recreational facilities.

Keywords: Male construction workers, psychological distress, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

In India, emerging trends such as globalization and industrialization have led to a booming real estate and construction industry.[1] This sector contributes significantly to national GDP.[2] The expanding and fast-growing construction sector in general and a lack of employment opportunities in other sectors have drawn large number of workers to this sector.[3] The construction industry, which mainly provides employment to unskilled workers forms the second largest unorganized sector in India after agriculture.[3,4]

Currently, more than 25 million of the workforce is engaged in the construction industry in India.[4,5] These construction laborers as a part of the unorganized workforce remain the most exploited with the denial of basic amenities to maintain an optimal standard of living. Uncertain working hours, lack of basic amenities, and inadequacy of welfare facilities are the major drawbacks in the sector.[6,7] Several factors such as temporary employment, fragile employer-employee relationship, and risk of life due to lack of occupational health and safety measures add to the woes of this sector's workforce. Most of the migrant workers in the construction sector are disadvantaged compared to the native population and they often have a low socioeconomic status with no access to either health care or social services.[1]

The workers engaged in this industry are victims of various occupational disorders and psychosocial stresses, which lead to reduced productivity.[8] Poor working conditions, exploitation, increased workplace insecurities, and lack of health benefits can lead to poor quality of life (QOL) and psychological distress among workers.[9,10] The performance of a worker is usually accounted for by the output; sound health including mental and social well-beings is essential for proper functioning of a worker.[6]

There are a few studies that have been conducted on the general health and social problems among female construction workers.[11,12,13] But very few studies are available among male construction workers.[2] Given this background, we have decided to undertake this study that would assess psychological distress, QOL, and related aspects.

Objectives

To assess the QOL among male construction workers

To assess the prevalence of probable psychological distress among male construction workers

To study the factors associated with both QOL and psychological distress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted at a construction site in Anchemuskur village, Malur Taluk in Kolar district, Karnataka, India between September 2013 and November, 2013. Using a mean QOL score of 71.9 and standard deviation of 14.7 with 2% relative precision at 95% confidence interval, the sample size was calculated to be 404.[14] The construction site in a Anchemuskur village was chosen based on convenience and large workforce. Male construction workers at the site who were above the age of 18 years and were working in the present site for a period more than 1 month were included in the study. The total number of male construction workers in that site was 1,100. Among them, 404 male workers were enrolled by consecutive sampling. The study tools used were described as following:

Part 1: Sociodemographic details and the study variables such as hours of work, morbidities, and habits of the study population

Part 2: The World Health Organization (WHO) QOL-BREF allows a detailed assessment of each individual facet relating to QOL. It has four domains (physical health, psychological relationship, social relationship, and environment) and 26 questions. Out of the 26 questions, seven are related to physical health, six to psychological status, three to social support, and eight to the environmental domain of the patient. The physical domain mainly includes activities of daily living, dependence on medicinal substances, medical aids, energy, fatigue, mobility, pain, discomfort, sleep, and rest. The psychological domain mainly includes bodily image and appearance, negative and positive feelings, self-esteem, personal beliefs, thinking, and concentration. The social domain consists of questions related to personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity. The environmental domain mainly includes financial resources, physical safety and security, health and social care, accessibility and quality, working/home environment, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, participation in and opportunities for recreation/leisure activities, physical environment, and transport. In addition, two items from the overall QOL and general health facet have been included. After drawing raw scores from the questionnaire, they are converted into the transformed score with the help of a table, which is considered to be the final score in that particular domain. As no cutoff points exist for good and poor QOL measured by WHO QOL-BREF, the four domain scores were scaled in a positive direction with higher scores indicating a higher QOL[15,16]

Part 3: 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) is a screening tool, designed to identify short-term changes in mental health (depression, anxiety, social dysfunction, and somatic symptoms). It is a pure state measure, responding to how much a subject feels that the present state over the past few weeks has been relatively different. It consists of 12 questions and each question has four responses using a Likert scale with a range of 0-3. Out of the total score of 36, a score of >15 indicates distress and a score >20 suggests severe problems and psychological distress.[17,18,19,20,21,22]

The structured interview schedule was translated into Hindi and Kannada using the standard procedure and back-translation was done to ensure quality. A pilot study was conducted in a nonstudy area and suitable modifications were incorporated. The consent was obtained from the construction company's management after informing them about the need and the purpose of the study. Then written informed consent was obtained from the workers and the interview schedule was administered to the workers and data were collected.

Statistics and analysis of the data

The data were coded and entered in Microsoft Excel and all the statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0, IBM. Sample characteristics were described by mean [standard deviation (SD)] and percentage (N) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Pearson Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used to find an association between two categorical variables. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to find the correlation between outcome and sociodemographic variables. Independent sample t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare the means between the groups. Linear regression analysis was used to predict the QOL and psychological distress using associated factors. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic details

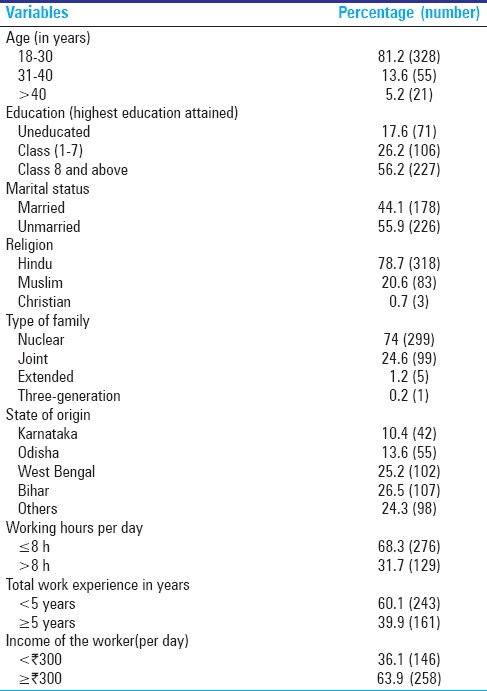

A total of 404 subjects were interviewed. Among them, 81.2% (328) were in the age group of 18–30 years and the mean age was 25.6 years (SD: 7.3 years). Most of the respondents 78.7% (318) were Hindus, 74% (299) were from nuclear families, and 82.6% (333) were literate. The mean number of years of schooling was 7.1 years (SD: 4.2 years). A vast majority of the workers, i.e., 89.6% (362) were from outside the state of Karnataka. Nearly one-third of the participants, i.e., 31.9% (129) were reported to be working for more than 8 h a day and the mean number of hours of work was 8.7 h (SD: 1.6 h). Most of the participants, i.e., 60.1% (243) had work experience of less than 5 years with a mean experience of 4.9 years (SD: 5.5 years). The mean daily income of workers was  329.7 (SD:

329.7 (SD:  141). The sociodemographic profile of the study population is shown in Table 1.

141). The sociodemographic profile of the study population is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the study population

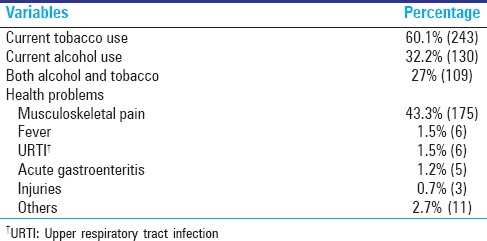

Current health status and habits

The prevalence of self-reported tobacco and alcohol use was 60.1% (243) and 32.2% (130), respectively, and 27% (109) used both tobacco and alcohol. Most of the workers, i.e., 43.3% (175) complained of musculoskeletal pain. However, very few workers reported incidents of injuries. Musculoskeletal pain was reported by the workers who worked >8 h per day compared to ≤8 h per day (χ2 = 188.1, P < 0.001). The details of the current habits and illness are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Morbidity profile and habits of the study populations

Quality of life and psychological distress among workers

The mean scores of various domains of QOL were 68.5 ± 13.7 (physical), 59.9 ± 13.5 (psychological), 64.3 ± 16.4 (social), and 44.1 ± 12.8 (environmental). On the self-rating scale, 40.1% (162), 45.3% (183), and 14.6% (59) of the workers were rated as having good, average, and poor QOL, respectively. Among the workers, 53.2% (215) were rated as having good health, 33.4% (135) as having average health, and 13.4% (54) as having poor overall health. A higher educational status and higher income were associated with good QOL. Increasing age and psychological distress were associated with poor QOL. The mean domain scores (physical) was found to be significantly different (P ≤ 0.001) among married (65.79 ± 13.9) and unmarried workers (70.36 ± 12.1) using independent samples t-test with a higher mean score among unmarried workers. This indicates a poor physical QOL among married workers compared to unmarried workers. No association was found between factors such as hours of work, religion, type of family, use of tobacco or alcohol, state of origin, morbidity, and QOL of workers.

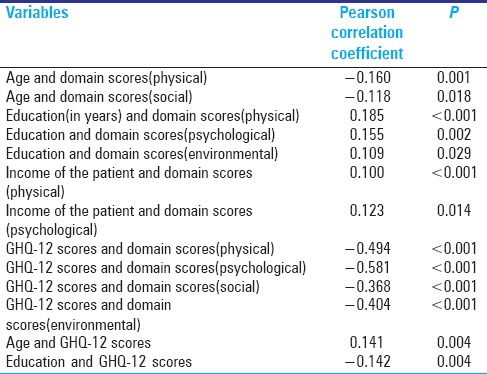

Among the 404 workers, 27.5% (111) screened positive for psychological distress using GHQ-12 (scores >15) and 8.2% (33) screened positive for severe psychological distress (scores >20). There was a significant positive correlation between age and distress (GHQ-12 scores) and a negative correlation between education and distress as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation of quality of life and psychological distress with associated factors

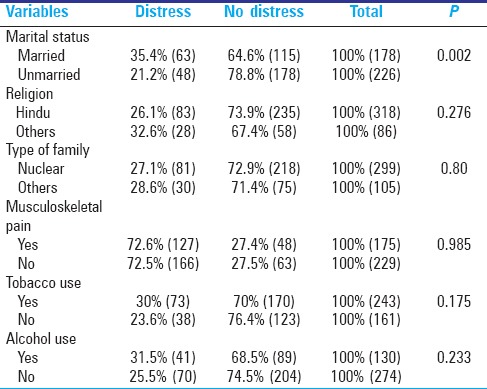

Pearson Chi-square test was used for assessing the plausible association between categorical variables and psychological distress. The details are shown in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Association of certain factors with psychological distress

The mean GHQ-12 score was found to be significantly different (P = 0.002) among married (13.6 ± 4.9) and unmarried (12.11 ± 4.7) workers, indicating more psychological distress among married workers using independent t-test. Similar differences were found between tobacco users (13.19 ± 4.6) and nonusers (12.17 ± 5.2) with more distress among tobacco users (P = 0.046) However, there was no significant association between tobacco use and distress using Chi-square test.

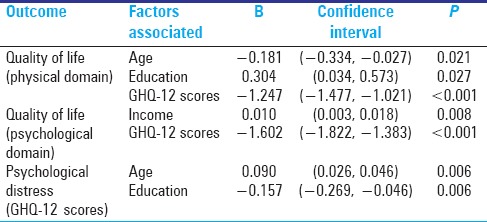

All the factors that were found to be significantly associated (P < 0.05) in the primary analysis were taken up for multiple regression analysis. Factors such as increasing age, lower educational status, lower income, and psychological distress were associated with low QOL. Marital status was not found to be significantly associated with QOL in the regression model. Similarly, only factors such as age and educational status were found to be associated with psychological distress. The details of the regression analysis are shown in the Table 5.

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis to predict the outcome

There were no statistically significant association found between factors such as hours of work, religion, type of family, use of alcohol, state of origin, morbidity, and psychological distress (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

A total of 404 male construction workers were included in this study. A majority of the workers (81.2%) belonged to the age group of 18–30 years with a mean age of 25.6 years (SD: 7.3 years). This finding was similar to the studies conducted among construction workers from Surat in Gujarat, India and Mumbai in Maharashtra, India where the mean age of the workers was 23 ± 7.31 years and 26.25 ± 8.49 years, respectively.[2,6] The educational status of the workers was found to be better compared to other studies with nearly 83% of the workers being educated.[2,6,23] Most of the workers were migrants from Bihar and West Bengal in India. Other studies also showed that a majority of the workers were from states such as Bihar, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan.[2,6] The present study showed that nearly one-third of the participants were working for than 8 h per day with a mean of 8.7 h (SD: 1.6 h). The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain was 43.3%. Similar results were found in other studies, which reported prevalence in the range of 20-45%.[2,24,25] The presence of musculoskeletal pain was more among the participants who worked for more than 8 h and this association was significant. A similar finding was observed in another study conducted among construction workers in Surat where the mean number of working hours in a day was 8.5 ± 0.8 h and the pain was more among the people who worked for >8 h.[2] The mean income of the workers was  329.7 (SD:

329.7 (SD:  141). The prevalence of injuries among the workers in this study was found to be very less compared to other studies.[2,26] The probable reasons stated by the participants were that the particular site dealt with only single-floor buildings and hence, the chances of falls and injuries were less; this could also be due to underreporting. It was difficult to capture the data on injuries as there was no system of documenting the incidence of injuries at the worksite.

141). The prevalence of injuries among the workers in this study was found to be very less compared to other studies.[2,26] The probable reasons stated by the participants were that the particular site dealt with only single-floor buildings and hence, the chances of falls and injuries were less; this could also be due to underreporting. It was difficult to capture the data on injuries as there was no system of documenting the incidence of injuries at the worksite.

The prevalence of self-reported tobacco use in any form (60.1%) and alcohol use (32.2%) was high among the study population. Other studies have shown that the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol use ranged 45-50% and 6-37%, respectively.[2,6,23,26]

Mean scores of various domains of QOL were 68.5 ± 13.7 (physical), 59.9 ± 13.5 (psychological), 64.3 ± 16.4 (social), and 44.1 ± 12.8 (environmental). On the self- rating scale, 59 (14.6%) workers were rated as having poor QOL. Among all the four domains, the workers scored poor in the environmental domain, which mainly deals with living and working conditions, safety, leisure activities, and health care. Workers were dissatisfied with the facilities provided to them including health care. During the interview, many participants stated that had to travel long distances to access health care. Similar results were found in other studies that assessed the living condition of workers. Lack of safety and other basic facilities coupled with long working hours might be the reason behind the high prevalence of tobacco and alcohol use among them. Factors such as increasing age, being currently married, lower educational status, and lower income were found to be significantly associated (P < 0.05) with poor QOL. There was a significant negative correlation between QOL and psychological distress; when one increased other decreased and vice versa. The prevalence of probable psychological distress among workers was found to be 27.5%. Increasing age, marital status, use of tobacco, and lower educational status were the factors associated with psychological distress. The prevalence of distress among construction workers in Kolkata in West Bengal, India was found to be 60.4% and studies have been conducted among female garment workers, which showed a prevalence of 45.1%.[21]

QOL and distress among workers in other occupations were studied in India. In spite of an extensive literature search, we could not find many study dealing with QOL and distress among male construction workers in India.

As the study had a cross-sectional design, it was difficult to find out the direction of association--whether psychological distress is leading to poor QOL or vice versa. In this study, we have mainly considered distress as an exposure and poor QOL as an outcome. However, the high prevalence of psychological distress, especially in this younger age group workers can adversely affect their productivity and economy in the long run. In addition to that, psychological distress with poor working conditions can increase the chance of accidents at the worksite. Many studies from outside India have shown that psychological problems among workers can reduce productivity.[8,9,10] Many studies conducted in the past only looked at the physical domain and most of the time, psychological distress can present as a physical problem among the workers; it is mandatory to look at the psychological domain as well. The limitations of this study are the nonrandom sampling method employed and the absence of assessment of workers’ productivity. The poor scores in the environmental domain imply a need to improve workplace amenities. All the workers who screened positive for psychological distress were referred to our community psychiatry clinic in the rural field practice area and were started on treatment if it turned out to be necessary.

CONCLUSION

The QOL in the environmental domain which mainly deals with living conditions, health and recreational facilities was found to be poor and there was a high prevalence of probable psychological distress among workers. This indicates a need for improving workplace amenities, access to health and recreational facilities in this group.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pandit N, Trivedi A, Das B. A study of maternal and child health issues among migratory construction Workers. Healthline. 2011;2:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel HC, Moitra M, Momin MI, Kantharia SL. Working conditions of male construction worker and its impact on their life: A cross sectional study in Surat city. Natl J Community Med. 2012;3:652–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hari Priya SK. Prepared for the Global Network for Women's Advocacy and Civil Society. Delhi, India: Charities Aid Foundation; [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 27]. Violence against women construction workers in Kerala, India. Available at https: //www.ciaonet.org/attachments/11887/uploads . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad N, Rao VK, Nagesha HN. Study On Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Schemes/Amenities in Karnataka. SASTech Journal. 2011;10:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhas AC, Helen MJ. Social Security for Unorganised Workers in India. MPRA Paper No. 9247. 2008. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 27]. Available from: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/9247/

- 6.Adsul BB, Laad PS, Howal PV, Chaturvedi RM. Health problems among migrant construction workers: A unique public-private partnership project. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2011;15:29–32. doi: 10.4103/0019-5278.83001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dileep Kumar M. Inimitable issues of construction workers: Case study. Br J Econ Finance Manage Sci. 2013;7:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang PS, Simon GE, Avorn J, Azocar F, Ludman EJ, McCulloch J, et al. Telephone screening, outreach, and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1401–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dewa CS, Lin E, Kooehoorn M, Goldner E. Association of chronic work stress, psychiatric disorders, and chronic physical conditions with disability among workers. Psychiatric Serv. 2007;58:652–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joling CI, Proper KI, Blatter BM, Bongers PM. A work site prevention program for construction workers: Design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:336. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papola TS, Partha PS. Growth and structure of employment in India. Long-Term and Post-Reform Performance and the Emerging Challenge. Institute for Studies in Industrial Development. A Study Prepared as a Part of a Research Programme structural changes, industry and employment in the Indian economy Macro-economic Implications of Emerging Pattern. 2012. Sponsored by Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) 2012. [Last cited on 2014 Dec 27]. Available from: http://isidev.nic.in/pdf/ICSSR_TSP_PPS.pdf .

- 12.Tikoo S, Meenu Work place environmental parameters and occupational health problems in women construction workers in India. Glob J Manage Bus Stud. 2013;3:1119–28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devi, Kiran UV. Status of female workers in construction industry in India: A review. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 2013;14:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHOQOL-BREF. Questionnaire. 1997. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 27]. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/seaqol/docs/WHOQOLBREF .

- 15.The World Health Organization Quality Of Life – Whoqol-bref. Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment. [Last accessed on 2014 Dec 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/76.pdf .

- 16.Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pevalin DJ. Multiple applications of the GHQ-12 in a general population sample: An investigation of long-term retest effects. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:508–12. doi: 10.1007/s001270050272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg D. Identifying psychiatric illnesses among general medical patients. Br Med J. 1985;291:161–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6489.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.General Health Questionnaire. EHS M270: Work and Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A, Deepika S, Taly AB, Srivastava A, Surender V, Thyloth M. Quality of life and psychological problems in patients undergoing neurological rehabilitation. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2008;11:225–30. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.44557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanbhag D, Joseph B. Mental health status of female workers in private apparel manufacturing industry in Bangalore City, Karnataka, India. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health. 2012;4:1893–900. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bansal V, Goyal S, Srivastava K. Study of prevalence of depression in adolescent students of a public school. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:43–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laad PS, Adsul BB, Chaturvedi RM, Shaikh M. Prevalence of substance abuse among construction workers. Paripex Indian J Res. 2013;2:280–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valsangkar S, Sai KS. Impact of musculoskeletal disorders and social determinants on health in construction workers. Int J Biol Med Res. 2012;3:1727–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telaprolu N, Lal B, Chekuri S. Work related musculoskeletal disorders among unskilled Indian women construction workers. Natl J Community Med. 2013;4:658–61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiwary G, Gangopadhyay PK, Biswas S, Nayak K. Psychosocial stress of the building construction workers. Hum Biol Rev. 2013;2:207–22. [Google Scholar]