Abstract

Smoke agglomerates are made of many soot sphcres, and their light scattering response is of interest in fire research. The numerical techniques chiefly used for theoretical scattering studies are the method of moments and the coupled dipole moment. The two methods have been obtained in this tutorial paper directly from the monochromatic Maxwell curl equations and shown to be equivalent. The effects of the finite size of the primary spheres have been numerically delineated.

Keywords: agglomerates, coupled dipolc method, light scattering, method of moments, smoke

1. Introduction

Electromagnetic scattering problems involving complicated geometries are treated numerically nowadays. Apart from some low- or high-frequency methods [1, 2] and the T-matrix method [3], implementation of most numerical techniques entails a partitioning of the region occupied by the scatterer into may subregions. This is generally true whether a differential formulation is used or an integro differential formalism.

The method of moments (MOM) [4–6], as applied to an inhomogeneous dielectric scatterer, is an approach based on the evaluation of an electric field volume integral equation over the region occupied by the scatterer. This region is partitioned into a number of subregions; the electric field in each subregion is represented by a subregional basis function; and the volume integral equation is converted into a set of simultaneous algebraic equations that are solved using standard procedures. The subregions are generally cubes, although the relevant self-terms are usually evaluated as that of equivoluminal spheres.

Whereas the MOM is an actual field formalism, the coupled dipole method (CDM) is based on the concept of an exciting field. The CDM was formulated intuitively in 1969 by Purcell and Pennypacker [7] for dielectric scatterers, although it had by that time a rich history spanning many decades [8]. Conceived from a microscopic viewpoint, the CDM has only a semi-microscopic basis; indeed, the operational basis for applying the CDM to boundary value problems is totally macroscopic [9]. Both the MOM and the CDM were recently extended to bianisotropic scatterers and their respective weak and strong forms were shown to be equivalent [10].

This tutorial paper contains a complete derivation of the MOM and the CDM for the scattering of time-harmonic electromagnetic waves by an inhomogeneous dielectric object possessing an isotropic permittivity, the starting point of the exercise being the monochromatic Maxwell curl equations. A central topic of the paper is the elucidation of the relationship between the MOM, which is widely used in electrical engineering, and the CDM, which is motivated by concepts in atomic physics [7]. Our treatment is directed towards the researcher who is interested in understanding these methods but who may not be a specialist in electromagnetic field theory.

A current topic of considerable interest is light scattering by agglomerated structures made up of individual spheres arranged in a low-density structure. Examples of such structures include smoke agglomerates formed in fires or internal combustion engines; various materials produced in combustion systems including silica and titanium dioxide; and, perhaps, interstellar dust. The earliest relevant analyses [11, 12] of light scattering from smoke were based on the Rayleigh-Debye approximation, in which the field exciting any particular primary sphere is taken to be just the field that is actually incident on the agglomerate. Such a procedure neglects multiple scattering effects, and is acceptable for primary spheres with size parameter (= radius multiplied by the free space wavenumber) less than about 0.2. The typical size parameters for the smoke agglomerates mentioned above lie in the range 0.1 to about 0.25 at visible frequencies.

Both the CDM [13, 14] and the MOM [15, 16] have been applied to compute scattering from smoke agglomerates in the recent past, since neither technique suffers from the limitations of the Rayleigh-Debye approximation. While the MOM and the CDM are expected to give the same results for infinitesimally small size parameters [17], the methods – as ordinarily used – do not yield identical results as the primary sphere size increases [18, 19]. This is because the CDM has been used chiefly in what may be called its weak form, while it is the strong form of the MOM that is in standard usage [10]. The strong form is valid for larger primary spheres because the effect of the singularity of the free space dyadic Green’s function is better estimated therein than in the weak form. This becomes clearer in the following sections.

2. Volume Integral Equation

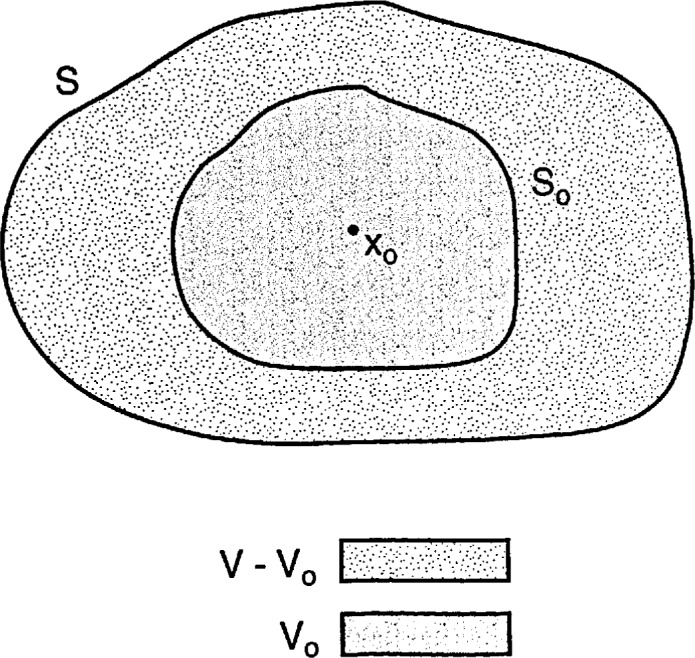

As is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1, let all space be divided into two mutually disjoint regions, Vint and Vext, that are distinguishable from each other by the occupancy of matter. The region Vext is vacuous; hence,

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the scattering problem. The unshaded region Vext extends to infinity in all directions, while the shaded regions collectively constitutc Vint.

The region Vint is filled with an isotropic, linear, possibly inhomogeneous, dielectric continuum with frequency dependent [exp(−iωt)] constitutive equations

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where ϵr(x) is the complex relative permittivity scalar. The square root of ϵr(x) is the local complex refractive index, Imag [ωϵ0ϵr(x)] is the local conductivity, and ω is the circular frequency.

There is no requirement that Vint be a simply-connected convex region. Sharp corners and cusps should be absent, it being preferable that the boundary surface that separates Vint from Vext be at least once-differentiable everywhere to enable the unambiguous prescription of a unit normal at every point on it. Furthermore, the maximum linear extent of Vint must be bounded so that only the region Vext extends out to infinity in all directions.

The monochromatic Maxwell curl equations, in the absence of any externally impressed sources, are given in Vext as

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

with 0 denoting the null vector. Similarly, in Vint we have

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

On rewriting Eq. (4b) as

| (4c) |

and comparing it with Eq. (3b), we are able to state the Maxwell curl equations everywhere as

| (5a) |

| (5b) |

In Eq. (5b), the volume electric current density J(x) ≡ 0 for x ∈ Vext, but

| (5c) |

In this fashion a volume electric current density has effectively replaced the dielectric matter occupying the region Vint [20, Sec. 3–11].

The volume electric current density J(x) defined by Eq. (5c) is not a fictitious entity in the present context. We must remember that, while the region Vext is vacuous, the region Vint is occupied by dielectric matter. The monochromatic polarization current density in this dielectric matter is given by

| (6a) |

while the conduction current density is given by

| (6b) |

It is now easy to see that

| (6c) |

which implies that J(x) is not merely a mathematically convenient quantity for dielectric scatterers.

It is enough that we look for the solution of the differential equations (5a, b) in terms of only the electric field, since the magnetic field everywhere may be obtained from Eq. (5a) if the electric field is known everywhere: H(x) = ∇ × E(x)/iωμ0. On taking the curl of both sides of Eq. (5a), and then substituting for ∇ × H(x) from Eq. (5b) in the result, we get

| (7) |

where k0 = ω(μ0ϵ0)1/2 is the free space wavenumber. We take cognizance of the fact that when J(x) is set equal to zero everywhere, Eq. (7) reduces to the celebrated vector Helmholtz equation.

As shown in Appendix A, it follows from Eq. (7) that the electric field E(x) is the solution of the volume integral equation

| (8a) |

or, equivalently,

| (8b) |

on using Eq. (5c). Here

| (8c) |

is the free space dyadic Green’s function and I is the identity dyadic. The field Einc(x) is the solution of Eq. (7) when J(x) ≡ 0 for all x ∈ Vint + Vext, and is the electric field existing in Vint + Vext if ϵr(x) = 1 for all x ∈ Vint. The standard radiation conditions are satisfied by the right sides of Eqs. (8a, b) as k0|x|→∞ [21].

3. Intermediate Remarks

Equation (8a) is utilized in setting up the CDM, while the integral Eq. (8b) is solved in the MOM, and it is this commonality that partially begets the algorithmic equivalence of the two techniques. In setting up the solutions of Eq. (7) in the form of the integral Eqs. (8a, b), we have brought in two significant topics that need some rumination right now: (i) dyadics and (ii) the free space dyadic Green’s function.

Dyadics are as American as apple pie, being the brainchildren of Josiah Willard Gibbs. In 1884, Gibbs circulated a pamphlet introducing the concept and nomenclature of dyadics. Mathematics books with dyadic notation were written every so often earlier in this century, but most mathematicians appear to have eventually discarded dyadics in favor of tensors. In electromagnetics, though, dyadic notation has been used with great profit, the books by van Bladel [22], Fedorov [23] and Chen [24] being immensely popular. A short exposition on dyadics was brought out by Lindell [25] in 1981, and is much recommended to the interested reader.

A dyadic serves as a linear mapping from one vector to another vector; thus, a dyadic D is a mapping from a to b given by b = D · a. This property leads to the idea of a dyad that is composed of two vectors, i.e., D12 = d1d2. It follows that D12 · a =d1(d2 · a) and a · D12 = (a · d1) d2 are vectors, and D12 × a = d1(d2 × a) and a × D12 = (a × d1)d2 are dyads, and the oft-used appellation bivectors for dyads appears justified [26]. Because a dyadic can be written as the sum of dyads, the general representation of a dyadic is the sum D = Σkm Dkmdkdm [27].

The identity dyadic I is such that D · I = D = I · D, and the null dyadic 0 is such that D · 0 = 0 = 0 · D. The simplest antisymmetric dyadic is u × I, where u is any vector of unit length. Even vector differential operators can be thought of as dyadics; thus, the curl operator is written as ∇ × I, and the divergence operator as ∇ · I, in dyadic notation. It is not possible for us to go through all the wonderful properties of dyadics than can be exploited in theoretical electromagnetics research, so we refer the interested reader to the compendiums in the books by Chen [24], van Bladel [22], and Varadan et al. [28]. The main feature of computational significance is that, as dyads are bivectors, all dyadics used in this paper can be thought of as 3 × 3 matrices.

The second issue concerns the singularity of the dyadic Green’s function G(x, x′) used in Eqs. (8a, b) and defined in Eq. (8c): the factor exp (ik0 |x−x′|)/4π|x−x′| goes to infinity as |x−x′|→0. When evaluating G(x, x′), the second derivatives therefore have to be carefully handled. As shown by van Bladel [29], the classical procedure leads one to write

| (9) |

where P.V. stands for “principal value.” When computing the P.V. integral on the right side of Eq. (9), an infinitesimally small spherical region centered about the point x′ = x is excluded from the domain of integration. Computing the P.V. integral is not problematic because [30]

| (10) |

is not singular when the source point x′ and the field point x do not coincide; here X = x − x′ and ux = X/|X|. Yaghjian [31] has modified the right side of (9) to an expression wherein the excluded infinitesimal region need not be spherical.

We will use an alternative approach to evaluate the integral (9), as shown in Appendix 2. In this approach [6, 10, 32], the region of integration is split into two regions: one region includes the point x' = x in its interior, while the second one is the remainder. Use is made of Gauss’ theorem and the Green’s function for Poisson’s equation to determine this integral. This procedure is attractive as it places very little restrictions on the shape and the size of the region surrounding the point x′ = x.

4. The Method of Moments

The method of moments is a general mathematical procedure for transforming a linear operator equation into a set of simultaneous algebraic equations, and the interested reader is referred to [4], Chap. 1, for a simple introduction. We are, however, confining ourselves here to the application of MOM to electromagnetic scattering problems.

Although the MOM has grown increasingly sophisticated in the last decade [6, 33], a simple version [5] suffices for the easy conversion of the integral equation (8b) into a set of simultaneous algebraic equations. We begin by partitioning the scatterer region Vint into simply connected subrogions Vm, 1 ≤ m ≤ M, each bounded by a closed surface Sm, so that Eq. (8b) can be transformed to

| (11) |

The main features of this partitioning scheme are as follows:

- Each subregion Vm is modeled as being homogeneous such that

(12) The maximum linear cross-sectional extent 2am of Vm is such that am/λ < 0.1 and am|ϵr,m1/2|/λ < 0.1; that is, the dimension am is no more than a tenth of the wavelength λ in the exterior region Vext as well as of the wavelength in the subregion Vm.

The surface Sm that bounds the subregion Vm is sufficiently smooth so as to be at least once differentiable, which enables the unambiguous prescription of a normal at any point on Sm.

Satisfaction of these three conditions, in practice, means that the union ΣmVm of the subrogions is only approximately coincident with the scatterer region Vint. Condition (i) can lead to an artificial material discontinuity across the interface of two adjacent subrogions, therefore the simple MOM algorithm given in this section works best when adjacent subrogions do not differ widely in their permittivities. Condition (ii) ensures that the spatial variations of the electromagnetic field inside each subregion are small enough so that each sub-region can be thought of as a dipole scatterer [34], though different authors use somewhat different upper bounds on the subregional size [35, 36]. Condition (iii) is mostly ignored by MOM users, their usual practice being to use cubical subrogions. Thus, the adequacy and the accuracy of the MOM – and the CDM – results depend in large measure on the adequacy of the partitioning scheme.

Two ancillary aspects of the partitioning scheme need to be stated for the simple MOM algorithm. First, the incident field must have slow enough spatial variations that it may be considered almost spatially constant over any subregion. Second, not only the permittivity but also the actual field is assumed spatially constant in each subregion. Together, these two assumptions constitute a long wavelength approximation [37], whose consequences are exploited in the MOM as well as in the CDM.

Let the volume of Vm be denoted by , and let xm denote a distinguished point (such as the centroid) lying inside Vm. On setting x = xk in Eq. (11) we get the relation

| (13a) |

Next, on using the approximation E(x) ≅ E(xm) for all x ∈ Vm and carrying out the integrations over all subrogions, we get

| (13b) |

where Em ≅ E(xm). In obtaining Eq. (13b) from Eq. (13a), we have accomplished the integration on the subregion Vm, m ≠ k, very simply by evaluating the specific integrand at xm and multiplying it by the volumetric capacity vm. The integral , on the other hand, has been estimated using Eq. (A2-5a).

With the assistance of Eqs. (5c) and (12), we transform Eq. (13b) into 3M simultaneous algebraic equations compactly stated in vector dyadic notation as

| (14a) |

where the 3M unknowns are the cartesian components of the fields Em, 1 ≤ m ≤ M. The dyadic kernel used in Eq. (14a) is given as

| (14b) |

where δkm is the Kronecker delta and the definition

| (15) |

follows from Eq. (A2-6a) with Xkm = xk − xm. In this straightforward and simple version of the MOM, wherein the electric field has been assumed to be piecewise constant over the scatterer region Vint, Eq. (14a) has to be solved for the three cartesian components of all Em for specified Einc(x).

Bearing in mind that all of our dyadics can be easily thought as 3 × 3 matrices, one can solve Eq. (14a) using a variety of matrix manipulation techniques. The Gauss elimination procedure [38] is simple but places a heavy demand on computer memory. Much less computationally intensive is the conjugate gradient method [39], which is now being heavily employed for MOM calculations [40].

Once all Em have been thus calculated, the scattered electric field in Vext can be computed as the sum

| (16) |

which expression follows from Eq. (8b). Now, from Eq. (A2-6a), we have the asymptote [41]

| (17a) |

correct to order 1/|x − xm|. Since all xm are generally distributed around the origin, the further reduction

| (17b) |

is reasonable. Finally, making the Fraunhofer approximation [42]

| (17c) |

on the left side of Eq. (17b) yields

| (17d) |

Consequently, the scattered electric field of Eq. (16) has the asymptotic representation

| (18) |

in the direction us in the far zone, with the far-zone scattering amplitude defined by

| (19) |

which shows quite clearly that us · Fsca(us) ≡ 0.

5. The Coupled Dipole Method

The heart of the MOM is Eq. (13b) which involves the electric field Ek that is actually present at xk. However, in the CDM we have to consider the electric field that excites the subregion Vk, each subregion being explicitly modeled as an electric dipole moment. In order to obtain an expression for this exciting field, we return to Eq. (8a), and rewrite it as

| (20) |

after partitioning the scatterer region precisely in the same manner as was done for the MOM solution. We know that Einc(x) is the field in the absence of the scatterer and that the quantity

is an electric field whose source clearly lies in the subregion Vm, m ≠ k. Thus, the whole of the right side of Eq. (20) is a composite electric field with multiple sources, but none of the sources lies in Vk. This composite electric field

| (21a) |

can be thought of as the field that excites Vk.

Since the left side of Eq. (20) must be equal to its right side, it follows that

| (21b) |

On setting x = xk in Eq. (21b), and completing the volume integration therein using Eq. (A2-5a), we get the expression

| (22) |

here, Jk = J(xk) and Eexc,k = (k)Eexc(xk). But, by virtue of Eq. (5c) we have

| (23a) |

which means that Eq. (22) reduces to

| (23b) |

whence,

| (23c) |

| (23d) |

Consistent with the long-wavelength approach, in the CDM we think of the equivalent electric dipole moment [9, 10]

| (24a) |

located at xk; thus,

| (24b) |

after using Eq. (21b), where

| (24c) |

is the polarizability dyadic of the dielectric region Vk.

We return to Eq. (21a) at this stage, set x =xk therein, and do the volume integrations; the result is the vector dyadic relation

| (25) |

in accord with the long-wavelength approximation. With the aid of Eq. (24a), we rewrite Eq. (25) as

| (26a) |

and the use of Eq. (24b) yields

| (26b) |

Equation (26b) constitutes the core of the CDM and, for numerical work, is best rewritten as the set of the 3M algebraic scalar equations

| (27a) |

for the cartesian components of Eexc,m, where the dyadic kernel

| (27b) |

The CDM algorithm is structurally just the same as the MOM algorithm, as is easily demonstrated by a comparison of Eqs. (27a, b) with Eqs. (14a, b). Hence, computational techniques for solving Eq. (27a) are the same as for solving Eq. (14a).

Once all Eexc,m have been obtained as the solution of Eq. (27a), one can use Eq. (24b) to find all pm and ascertain the scattered field as the sum

| (28) |

which relation follows from Eq. (8a). Equation (18) still applies for the scattered electric field in the far zone, but the far-zone scattering amplitude is now given by

| (29a) |

equivalently,

| (29b) |

Parenthetically, we remark here that the Rayleigh-Debye approximation for scattering by smoke agglomerates [11, 12] may be obtained by replacing Eexc,m in Eq. (29b) by Einc(xm).

6. Scattering and Absorption

The presence of a scatterer has two observable consequences insofar as the conservation of electromagnetic energy is concerned. A portion of the energy radiated by the source of Einc(x) is scattered in all directions by the scatterer. Another portion is absorbed by the scatterer and converted into other forms such as heat. All calculations pertaining to the scattered and the absorbed powers at a given circular frequency ω are made in terms of power averaged over the time period 2π/ω.

Because Fsca(us) is of the form [I − usus] · b, it follows that us · Fsca(us) ≡ 0, as has been mentioned earlier. By virtue of Eqs. (3a) and (18), we have

| (30) |

where η0 = (μ0/ϵ0)1/2 is the intrinsic impedance of free space. These observations imply that the scattered field in the far zone is Transverse Electro-Magnetic (TEM) in character.

The time-averaged scattered power per unit solid angle in the direction us is defined as

| (31a) |

with dΩ(us) ≡ sinθs dθs dϕs, as is customary in spherical coordinates, and the asterisk denoting the complex conjugate. After putting Eqs. (18) and (30) in Eq. (31a), we obtain

| (31b) |

consequently, we are able to ascertain the total time-averaged scattered power as the integral

| (31c) |

Unless the scatterer material is intrinsically lossless, there is absorption of electromagnetic energy in Vint. Because the scatterer is simply a dielectric object here, the time-averaged power absorbed in Vint may be computed as the volume integral

| (32a) |

from Poynting’s theorem for monochromatic fields [24, Chap. 2]. After using Eq. (2a) on the right side of this relation, we get the result

| (32b) |

Finally, after using Eq. (12) as well as the long-wavelength approximation made heretofore, we are able to reduce this expression to the sum

| (33) |

Because Em · Em* is purely real, no power absorption will take place in Vm if ϵr,m is purely real; indeed, Pabs ≡ 0, provided Imag [ϵr(x)] ≡ 0 for all x ∈ Vint.

Insofar as the MOM is concerned, the solution {Em; m = 1, 2,…, M} of Eq. (14a) may be directly substituted into Eq. (33) for the computation of Pabs. The calculation of Pabs in the CDM is only slightly more complicated: the exciting fields {Eexc,m; m = 1, 2,…, M} obtained by solving Eq. (27a) have to be substituted into Eq. (23c) to get {Em;m = 1,2,…, M}. Thus, an useful expression for CDM computations is

| (34a) |

where

| (34b) |

The total time-averaged power extinguished by the scatterer region is the sum

| (35) |

Quite often, one is interested in the extinction of the plane wave

| (36a) |

| (36b) |

where einc carries the units of volts per meter and uinc is a dimensionless unit vector such that einc · uinc = 0. In this case, the total time-averaged power extinguished by the presence of matter in Vint can be estimated using the forward scattering amplitude as [22, Chap. 8]:

| (37) |

Substitution of Eqs. (29a) and (36a) in this relation gives us

| (38a) |

whence,

| (38b) |

for use with the CDM. The MOM analog of Eq. (38b) is easily obtained by substituting Eq. (23b) therein; ergo,

| (38c) |

for use with the MOM.

7. Spherical and Cubical Subrogions

Although spheroidal and ellipsoidal subregions have been used [43, 44], it is commonplace in literature to have cubical or spherical subregions. CDM users are more comfortable with spherical subregions, while MOM users are fond of cubical ones. Cubes and spheres have the same dyadic L, and in many MOM codes the M dyadic of a cube is estimated as that of an equi-voluminal sphere; see Appendix C. Without any particular loss of generality therefore, we take the subregions to be spherical and of identical radii in the remainder of this paper.

Let the subregion Vk be the sphere of radius a with its center at xk. As a result, the volume vk = (4π/3)a3, the dyadic Lk = (1/3)I, and the dyadic Mk = (2/3k02)[(l − ik0a) exp(ik0a) − 1]I, as shown in Appendix C. Consequently, the MOM dyadic kernel given in Eq. (14b) reduces to

| (39a) |

| (39b) |

In the same manner, the CDM dyadic kernel of Eq. (27b) simplifies to

| (40a) |

| (40b) |

An analysis of the self-terms is crucial to the understanding of the MOM and the CDM. From Eq. (39a) it follows that the MOM self-term can be broken up as

| (41a) |

where

| (41b) |

and

| (41c) |

Both Ákk and Åkk should be called self-terms; instead, it seems only Åkk has been accorded that honor in some MOM papers, e.g., [16–19, 45].

The CDM self-term is somewhat obscure, being hidden as the polarizability dyadic tk of Eq. (24b). In the present instance, the polarizability dyadic reduces to a scalar because the subregion is spherical; hence,

| (42a) |

where

| (42b) |

and

| (42c) |

is the Mossotti-Clausius polarizability [46, 47] of the electrically small dielectric sphere.

Let k0a < < 1 in Eq. (41c) and Åkk be evaluated correct to order k03a3. Then,

| (43) |

and we observe that the (2ik03/3)αk/4πϵ0 term in the denominator of the right side of Eq. (43) is the radiative reaction term used by Draine [48] in his CDM formulation. More often, Åkk is evaluated correct only to the first order in k0a, leading to τk ≅ αk [7], and thereby giving rise to the semi-microscopic flavor of this numerical approach [9].

8. Strong and Weak Forms

The various approximations that can be made for the self-terms lead us to the strong and the weak forms of the MOM and the CDM [10]. In the strong forms (S-CDM & S-MOM), Eq. (A2-5a) is used to estimate the self-term (m = k) in Eqs. (13a) and (21b). In the Weak forms (W-CDM & W-MOM), Eq. (A2-7) is used in place of Eq. (A2-5a) for this estimation. For isotropic dielectric scatterers, the W-CDM is exemplified by Purcell and Pennypacker [7] using spherical subregions, and the S-CDM has become recently available [17] for the same problem. The S-MOM has been used for isotropic dielectric scatterers for many years [6, 33], but the idea of W-MOM is of more recent provenance [17].

The W-MOM corresponds exactly to the W-CDM, while the S-MOM corresponds exactly to the S-CDM. When all subregional volumetric capacities are very small, the S-MOM/S-CDM effectively transmutes into the W-MOM/W-CDM. Generally stated, therefore, it can be surmised that the scatterer region Vint must be broken up into a larger number of subregions when the W-MOM/W-CDM is used than if the S-MOM/S-CDM is used. Comparison of S-MOM results with the W-CDM results, with identical partitioning of the scatterer region, [e.g., 16, 18, 19], in some instances may be like comparing apples with oranges. The difference between S-CDM/S-MOM and W-CDM/W-MOM is solely due to the inclusion or the exclusion of the dyadic Mk in the expression for Akk, therefore computational time is marginally increased and the memory requirement negligibly, when one shifts from W-CDM/W-MOM to S-CDM/S-MOM.

9. Spherical Subregions and Finite-Size Effects

An assessment of the MOM and the CDM for isotropic dielectric scatterers with spherical subregions is now in order. To facilitate such a comparison, we reiterate that

| (44a) |

| (44b) |

and correspondingly,

| (45a) |

| (45b) |

We can evaluate the strong forms vis-a-vis the weak forms through the Taylor expansion of the ratio r/a about ϵr = 1, there being no need for us to continue the subscript k in the remainder of this paper. Using Eqs. (41b), (41c) and (42b), we get the expansion

| (46a) |

where Λ = [(1 − ik0a) exp(ik0a) − 1] has been used for convenience; and it becomes clear that the weak forms are poor approximations of the strong forms when the relative permittivity is significantly different from unity.

Likewise, the Maclaurin expansion of τ/α with respect to the size parameter k0a,

| (46b) |

indicates that the weak forms become increasingly inadequate as the size parameter of the subregion increases.

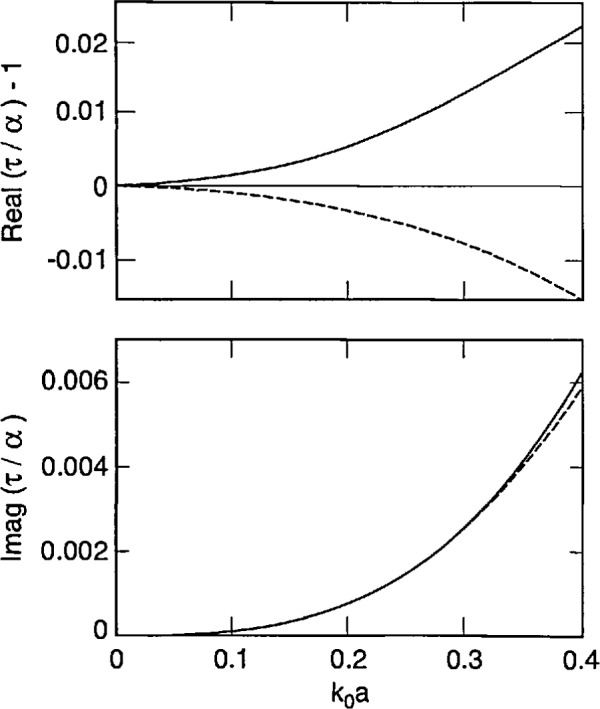

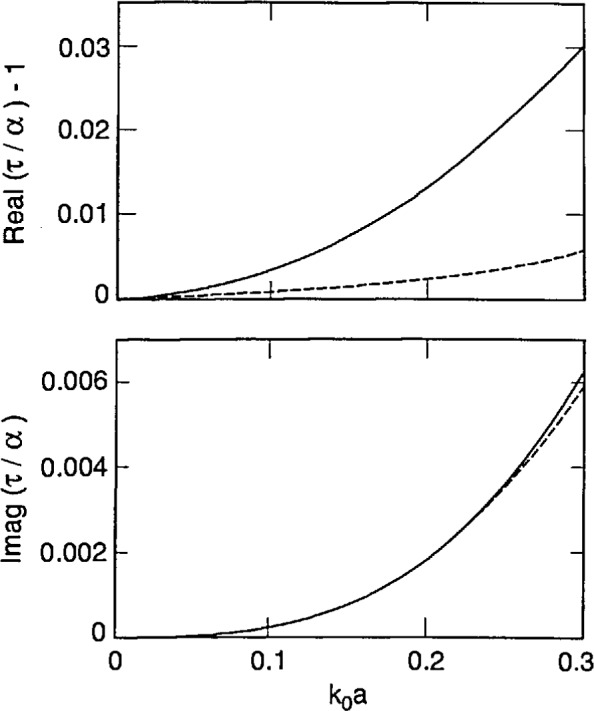

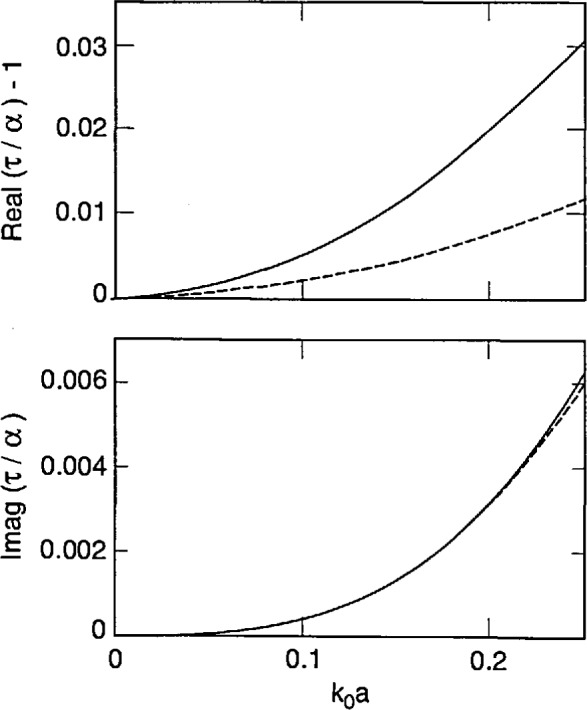

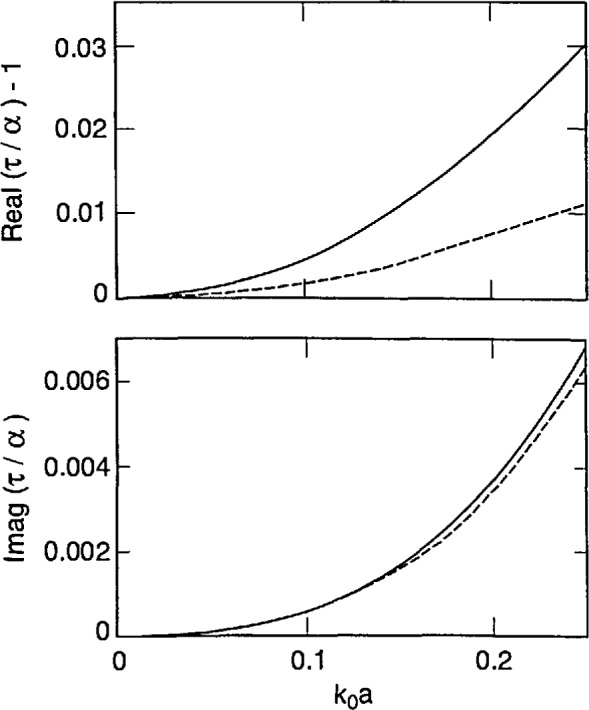

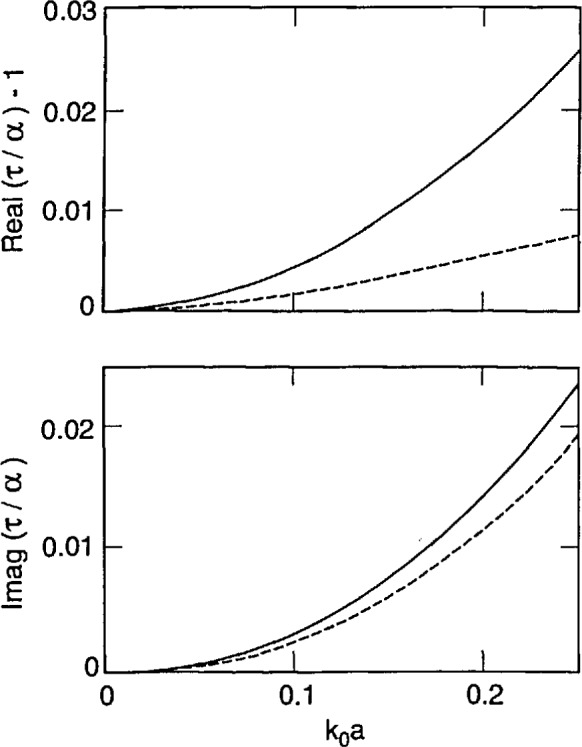

Equations (46a) and (46b) tell us that strong forms incorporate finite-size effects meaningfully, while the weak forms do so trivially. This conclusion is reinforced by Figs. 2–4 that show plots of τ/α versus the normalized radius k0a of an electrically small sphere for ϵr = 1.5, 2.5 and 4.0. In these figures we have ensured that the maximum value of k0a|ϵr1/2| is about 0.5. We observe – not surprisingly – that τ is complex while α is purely real for these input parameters. Furthermore, in all three figures the ratio |τ/α| lies between 1.02 and 1.03 when k0a|ϵr1/2| ≅ 0.5; while τ/α = 1 for k0a = 0, of course. Similar conclusions can be drawn from Fig. 5, wherein the calculations of τ/α have been reported for a lossy dielectric sphere with ϵr = 3.75 + 0.25i. These figures highlight the understanding on finite-size effects drawn from Eqs. (46a, b), and it follows that coarser partitioning of Vint may be acceptable when S-CDM/S-MOM is used than when W-CDM/W-MOM is used. These thoughts can be validated by careful examination of the graphs recently published by Ku [19].

Fig. 2.

Functions [τ/α − 1] (solid lines) and [τDB/α − 1] (dashed lines) as functions of the size parameter k0a of a spherical sub-region whose relative permittivity ϵr = 1.5; the Mossotti-Clausius polarizability α = 4πa3 ϵ0(ϵr − 1)/(ϵr + 2).

Fig. 3.

Same as Fig. 2, but ϵr = 2.5.

Fig. 4.

Same as Fig. 2, but ϵr = 4.0.

Fig. 5.

Same as Fig. 2, but ϵr = 3.75 + 0.25i.

The strong forms discussed above are not the only way of introducing finite-size effects, there being at least two more CDM algorithms available for that purpose. As alluded to earlier, Draine [48] replaced the Mossotti-Clausius polarizability by

| (47) |

However, τD is fully contained in τ, as we have seen in Eq. (43); and τD approaches α as the size parameter k0a becomes vanishingly small.

The second source for the incorporation of finite-size effects has been the Lorentz-Mie-Debye analysis for scattering by a dielectric sphere [46]. The electromagnetic field scattered by any object can be described in terms of a multipole expansion [49]. With inspiration from Doyle [50], Dungey and Bohren [51] introduced finite-size effects in the CDM by using the lowest order Mie coefficient – corresponding to the electric dipole term of the mutipole expansion – for the polarizability in place of the Mossotti-Clausius polarizability α. Thus,

| (48) |

was used in [47], with ψ(β) = β−1 sin(β) − cos(β), ∂ψ(β) = dψ/df/dβ, ζ(β) = − (1 + i/β) exp(iβ), and ∂ζ(β) = dζ/dβ.

Using Eq. (48), it can be shown that τDB approaches α as the normalized radius k0a becomes vanishingly small. This is also borne out in Figs. 2–5, wherein the computed values of τDB/α are compared with those of τ/α as functions of the normalized radius k0a for ϵr = 1.5, 2.5, 4.0 and 3.75 + 0.2i. The general behavior of τDB is the same as of τ: (i) τDB is complex even for purely real ϵr and (ii) the ratio |τDB/α| lies between 0.99 and 1.01 when k0a |ϵr1/2| ≅ 0.5 in these figures. A more remarkable observation is that |1 − τDB/α| ≤ |1 − τ/α|; in other words, τDB is closer to the Mossotti-Clausius polarizability α than τ is.

Draine [48] and Dungey and Bohren [51] concluded from their numerical investigations that D-CDM and DB-CDM, respectively, generally provide scattering results superior to those from W-CDM. This does not come as a surprise because the self-terms in W-CDM (or W-MOM) are estimated with the least accuracy. On the other hand, although it is difficult to provide general enough conclusions for the adequacy of either D-CDM or DB-CDM vis-a-vis that of the S-CDM/S-MOM, it is safe to state that any claims of superiority – based purely on the estimation of some gross parameter, such as the total scattering cross-section – are debatable. Indeed, the only good way of deciding on the superiority of S-CDM, D-CDM or DB-CDM is by making calculations for the specific problem under consideration: The scatterer region should be subdivided into different numbers of subregions, and computed data from the various algorithms for different partitioning schemes compared for the property of interest [52–54].

The refractive index of soot at visible frequencies has been measured by a variety of experimental techniques, and has been found to be dependent on the source materials [55]. We conclude with calculations of τ/α and τDB/α for ϵr = 2.40 + 2.38i, corresponding to a complex refractive index of 1.7 + 0.7i, in Fig. 6. It is not difficult to gather from this figure that conclusions drawn in the previous paragraphs of this section apply to light scattering by soot agglomerates.

Fig. 6.

Same as Fig. 2, but ϵr = 2.40 + 2.38i.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors (George W. Mulholland) was supported in part by the Pennsylvania State University Particulate Materials Center while on sabbatical leave at Pennsylvania State University. The authors thank Dr. Egon Marx (NIST), Prof. Dike Ezekoye (University of Texas at Austin), and Prof. W. S. Weiglhofer (University of Glasgow) for their constructive comments and criticisms. Thanks are also due to the external reviewers whose comments helped improve this tutorial paper.

Glossary

- 0

Null vector

- 0

Null dyadic

- a

Radius of a spherical subregion

- a, b, d1, d2

Arbitrary vectors

- am

(1/2) × maximum linear cross-sectional dimension of the sub-region Vm

- Akm

Dyadic kernel for the MOM equations

- Åkk, Ákk

Self-terms when MOM is used with spherical subregions

- b

Side of a cubical subregion

- B(x)

Magnetic flux density (weber per square meter)

- D(x)

Electric flux density (coulomb per square meter)

- einc

Electric field intensity amplitude of an incident plane wave

- E(x)

Electric field intensity (volt per meter)

- (m)Eexc(x)

Electric field intensity exciting the subregion Vm

- Ecxc,m

= (m)Eexc(Xm)

- Einc(x)

Incident electric field intensity

- Em

Electric field intensity at xm

- Esca(x)

Scattered electric field intensity

- Fsca(us)

Far-zone scattering amplitude in the direction us

- G(x, x′)

Free space dyadic Green’s function

- Gkm

= G(xk, xm)

- H(x)

Magnetic field intensity (ampere per meter)

- Hsca(x)

Scattered magnetic field intensity

- i

= (−1)1/2

- I

Identity dyadic

- J(x)

Electric current density (ampere per cubic meter)

- Jm

= J(xm)

- Jcond(x)

Conduction current density (ampere per cubic meter)

- Jpol(x)

Polarization current density (ampere per cubic meter)

- k0

Free space wavenumber (inverse meter)

- Lm, Mm, Tm

Depolarization dyadics for the three-dimensional subregion Vm

- M

Total number of subregions

- pm

Electric dipole moment equivalent to the subregion Vm

- Pabs

Time-averaged absorbed power

- Psca

Time-averaged scattered power

- Pext

Time-averaged extinguished power

- Qkm

Dyadic kernel for the CDM equations

- Sm

Closed surface of the three-dimensional subregion Vm

- t

Time (seconds)

- tm

Polarizability dyadic of the subregion Vm

- us

Unit vector denoting direction in the far zone

- uinc

Unit vector denoting propagation direction of an incident plane wave

- Vext

Three-dimensional region external to the scatterer

- Vint

Three-dimensional region occupied by the scatterer

- Vm

Three-dimensional subregion

- x

Three-dimensional position vector (meter)

- xm

Distinguished point inside the subregion Vm

- Xkm

xk-xm

- α

Mossotti-Clausius polarizability scalar of a spherical subregion

- αm

Mossotti-Clausius polarizability scalar of the m-th spherical subregion

- δkm

Kronecker delta

- δ(x–x′)

Dirac delta

- ϵ0

Permittivity of free space (= 8.854 × 10−12 farad per meter)

- ϵr

Relative permittivity

- ϵr(x)

Relative permittivity of dielectric matter occupying Vint

- ϵr, m

Relative permittivity of dielectric matter of the subregion Vm

- η0

Intrinsic impedance of free space (= 120 π ohm)

- Λ

= [(1 − ik0a) exp(ik0a) − 1]

- λ

= Wavelength in free space (= 2π/k0)

- μ0

Permeability of free space (= 4π × 10−7

- ω

Circular frequency (radian per second)

- Ω

Solid angle

- τ

Polarizability scalar of a spherical subregion

- τm

Polarizability scalar of the m-th spherical subregion

- τD

Draine’s polarizability scalar of a spherical subregion

- τDB

Dungey-Bohren polarizability scalar of a spherical subregion

- νm

Volume of the subregion Vm (cubic meter)

- ψ(β)

A Riccati-Bessel function of argument β

- ζ(β)

A Riccati-Hankel function of argument β

Biography

About the authors: Akhlesh Lakhtakia is Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics at the Pennsylvania State University. George W. Mulholland is Research Chemist and Group Leader, Smoke Dynamics Research Group at NIST. The National Institute of Standards and Technology is an agency of the Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce.

10. Appendix A. The Volume Integral Equation for the Electric Field

The free space Green's function G(x,x′) satisfies the dyadic differential equation

| (A1-1) |

where δ(x−x') is the Dirac delta function. Since J(x′) is not a function of x, it follows that ∇ × [G(x,x′) · J(x′)] = [∇ × G(x, x′)] · J(x′); hence,

| (A1-2) |

We multiply both sides of this equation by iωμ0 and integrate over all x′ to get

| (A1-3) |

whence,

| (A1-4) |

Now by comparing Eqs. (7) and (A1-4), it is not too arduous to convince ourselves that

| (A1-5) |

Remembering that for the present purposes J(x) is null everywhere except in Vint, we next obtain

| (A1-6) |

The solution of every linear differential equation can be divided into two parts: the particular solution that depends on the forcing function, J(x) being the forcing function here, and the complementary function that holds when the forcing function is identically zero everywhere. The right side of Eq. (A1-6) is the particular solution of Eq. (7), which has the complementary function Einc(x) satisfying

| (A1-7) |

Hence, the complete solution of Eq. (7) is

| (A1-8) |

which can be easily re-expressed as Eq. (8a).

11. Appendix B. The Self-Integral

The integral under consideration is given as

| (A2-1) |

where V is the region bounded by the surface S, as shown in Fig. 7, G(x, x′) is given by Eq. (8c), and the point x0 lies inside V. Because G(x, x′) is of the order 1/|x − x′|3 for |x − x′| ≅ 0, and becomes singular at x = x′, this integral has to be carefully treated.

Fig. 7.

For the evaluation of the integral in Eq. (A2-1) when x0 ∈ V and x′ ∈ V.

As shown by Fikioris [56], we can transform Eq. (A2-1) to

| (A2-2) |

where

| (A2-3) |

is an auxiliary dyadic related to the Green’s function for Poisson’s equation [10]; V0 is an exclusionary region bounded by the surface S0, as shown in Fig. 7; un is the unit normal to S0, pointing away from V0, at the point x′ ∈ S0. The exclusionary region V0 should be small but not necessarily infinitesimal, and it must be wholly contained within V. Moreover, there is no requirement that S0 be a miniature copy of S.

The use of the long-wavelength approximation b(x)≅b(x0) for all x ∈ V reduces Eq. (A2-2) to

| (A2-4) |

Since V is electrically small, but V0 need not be infinitesimal, we set V = V0 and S = S0 to have

| (A2-5a) |

where

| (A2-5b) |

| (A2-5c) |

The evaluation of M can be accomplished numerically for regions of different shapes using the coordinate-free (i.e., non-indicial) representations [24, Chap. 9]

| (A2-6a) |

| (A2-6b) |

where X = x−x′ and ux = X/|X|. The evaluation of the depolarization dyadic L is equally easy on a digital computer, and analytical expressions for L are available for the quite general ellipsoidal shapes [57].

If V is extremely small in electrical size, the simplification

| (A2-7) |

is permissible and leads to the weak forms of the MOM and the CDM.

12. Appendix C: The Self-Dyadics for Spherical and Cubical Regions

Let the region V in Appendix B be a sphere with radius a and center at x0. Without loss of generality due to the translational invariance of the right sides of Eqs. (A2-6a, b), we set x0= 0. Furthermore, we set x′ = r′ (u1 sinθ′ cosϕ′ + u2 sinθ′ sinϕ′ + u3 cosθ′), where |x′| = r′, (u1, u2, u3) is the triad of cartesian unit vectors, while (r′, θ′, ϕ′) represent the corresponding spherical coordinate system located at the center of the sphere. Hence,

Now,

| (A3-1) |

and

| (A3-2) |

likewise. It follows that

| (A3-3) |

In order to evaluate L for a spherical region, we note that un′ = x′/|x′| where x′ ∈ S; ergo, |x′| = a, and

| (A3-4) |

after using Eq. (A3-1).

If the region V in Appendix B were to be a cube of side b, we would get

| (A3-5) |

the same as that for a sphere. No expression exists for the dyadic M for a cube in closed form; however, it is commonplace in MOM practice to use the value for an equivoluminal sphere. Thus,

| (A3-6) |

because [(3/4π)1/3 b] is the radius of a sphere having the same volume as the cube of side b.

13. References

- 1.Massoudi H, Durney CH, Johnson CC. Long-wavelength electromagnetic power-absorption in ellipsoidal models of man and animals. IEEE Trans Microwave Theory Tech. 1977;25:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowlandson GI, Barber PW. Absorption of higher-frequency RF energy by biological models: Calculations based on geometrical optics. Radio Sci. 1977;14(6S):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varadan VV, Lakhtakia A, Varadan VK. Comments on recent criticism of the T-matrix method. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1988;84:2280–2284. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrington RF. Ficld Computation by Moment Methods. McGraw-Hill Book Publishing Company; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livesay DE, Chen KM. Electromagnetic fields induced inside arbitrarily shaped dielectric bodies. IEEE Trans Microwave Theory Tech. 1974;22:1273–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JJH. Generalized Moment Methods in Electromagnetics. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell EM, Pennypacker CR. Scattering and absorption of light by nonspherical dielectric grains. Astrophys J. 1973;186:705–714. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakhtakia A. General theory of the Pureell-Pennypackcr scattering approach, and its extension to bianisotropic scatterers. Astrophys J. 1992;394:494–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakhtakia A. Macroscopic theory of the coupled dipolc approximation method. Opt Commun. 1990;79:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakhtakia A. Strong and weak forms of the method of moments and the coupled dipolc method for scattering of time-harmonie electromagnetic fields. Int J Mod Phys C. 1992;3:583–603. [Google Scholar]; errata: 4, 721–722 (1993).

- 11.Berry MV, Percival IC. Optics of fractal clusters such as smoke. Optica Acta. 1986;33:577–591. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mountain RD, Mulholland GW. Light scattering from simulated smoke agglomerates. Langmuir. 1988;4:1321–1326. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson J. Test of a mean field theory for the optics of fractal clusters. J Mod Opt. 1989;36:1031–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singham SB, Bohren CF. Scattering of unpolarized and polarized light by particle aggregates of different size and fractal dimension. Langmuir. 1993;9:1431–1435. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iskander MF, Chen HY, Penner JE. Optical branching and absorption by branched chains of aerosol. Appl Opt. 1989;28:3083–3091. doi: 10.1364/AO.28.003083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ku JC, Shim KH. A comparison of solutions for light scattering and absorption by agglomerated or arbitrarily-shaped particles. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transfer. 1992;47:201–220. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakhtakia A. Towards classifying elementary microstructures in thin films by their scattering responses. Int J Infrared Millim Waves. 1992;13:869–886. [Google Scholar]; errata: 14, 663 (1993).

- 18.Hage JI, Greenberg JM. A model for the optical property of porous grains. Astrophys J. 1990;361:251–259. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku JC. Comparisons of coupled-dipole solutions and dipolc refractive indices for light scattering and absorption by arbitrarily shaped or agglomerated particles. J Opt Soc Amer A. 1993;10:336–342. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington RF. Time-Harmonic Electromagnetic Fields. McGraw-Hill Book Publishing Company; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones DS. Low frequency electromagnetic radiation. J Inst Maths Applies. 1979;23:421–447. [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Bladcl J. Electromagnetic Fields: Hemisphere; Washington, DC: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedorov FI. Theory of Gyrotropy (in Russian) Nauka i Tcknika; Minsk: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen HC. Theory of Electromagnetic Waves. McGraw-Hill Book Publishing Company; NewYork: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindell IV. Elements of Dyadic Algebra and Its Application in Electromagnetics. Helsinki University of Technology; 1981. (Radio Laboratory Report S 126). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulanger P, Hayes M. Electromagnetic plane waves in anisotropic media: An approach using bivectors. Philos Trans Roy Soc Lond A. 1990;330:335–393. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brand L. Vector and Tensor Analysis. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varadan VV, Lakhtakia A, Varadan VK, editors. Field Representations and Introduction to Scattering. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Bladcl J. Some remarks on Green’s dyadic for infinite space. IRE Trans Antennas Propagat. 1961;9:563–566. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiglhofer W. Delta-function identities and electromagnetic field singularities. Amcr J Phys. 1989;57:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaghjian AD. Electric dyadic Green’s functions in the source region. Proc IEEE. 1980;68:248–263. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang JJH. A unified and consistent vicw on the singularities of the electric dyadic Green’s function in the source region. IEEE Trans Antennas Propagat. 1982;30:463–468. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller EK, Medgycsi-Mitschang L, Newman EH, editors. Computational Electromagnetics: Frequency-Domain Method of Moments. IEEE Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DS. Numerical methods for antenna problems. Proc Inst Elec Eng. 1974;121:573–582. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen KM, Guru BS. Internal EM field and absorbed power density in human torsos induced by 1–500-MHz EM waves. IEEE Trans Microwave Theory Tech. 1977;25:746–756. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hagmann MJ, Gandhi OP, Durncy CH. Upper bound for cell size for moment method solutions. IEEE Trans Microwave Theory Tech. 1977;25:831–832. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Athanasiadis C. Low-frequency electromagnetic scattering by a multi-layered scatterer. Quart J Mech Appl Math. 1991;44:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carnahan B, Luther HA, Wilkes JO. Applied Numerical Methods: John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strang G. Introduction to Applied Mathematics. Wellesley-Cambridge Press; Wellesley, MA: 1986. Chap. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkar TK, editor. Application of Conjugate Gradient Method to Electromagnetics and Signal Analysis. Elsevier; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 41.We define g(x) =Tendx→∞ f(x) as a function that replicates the asymptotic behavior of f(x) as x→∞, “Tend” standing in for “tendency;” Limx→∞ [g(x)/f(x)] =1.

- 42.Goodman JW. Introduction to Fourier Optics. McGraw-Hill Book Publishing Company; New York: 1968. Chap. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singham SB. Intrinsic optical activity in light scattering from an arbitrary particle. Chem Phys Lett. 1986;130:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varadan VK, Lakhtakia A, Varadan VV. Scattering by beaded helices: Anisotropy and chirality. J Wave Mater Interact. 1987;2:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gocdecke GH, O’Brien SG. Scattering by irregular inhomogeneous particles via the digitized Green’s function algorithm. Appl Opt. 1988;27:2431–2438. doi: 10.1364/AO.27.002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohren CF, Huffman DR. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prinkcy MT, Lakhtakia A, Shanker B. On the extended Maxwell Gannett and the extended Brugge man approaches for dielectric indiclectric composites. Optik; 1993. Chronological propriety demands that Mossotti’s name be placed before that of Clausius; see. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Draine BT. The discrete dipolc approximation and its application to interstellar graphite grains. Astrophys J. 1988;33:848–872. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papas CH. Theory of Electromagnetic Wave Propagation. Dover Publications; New York: 1988. Chap. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doyle WT. Optical properties of a suspension of metal spheres. Phys Rev B. 1989;39:9852–9858. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.39.9852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dungey CE, Bohren CF. Light scattering by non-spherical particles: a refinement to the coupled-dipolc method. J Opt Soc Am A. 1991;8:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massoudi H, Durncy CH, Iskander MF. Limitations of the cubical block model of man in calculating SAR distributions. IEEE Trans Microwave Theory Tceh. 1984;32:746–752. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Varadan VV, Lakhtakia A, Varadan VK. Scattering by three-dimensional anisotropic scatterers. IEEE Trans Antennas Propagat. 1989;37:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- 54.West RA. Optical properties of aggregate particles whose outer diameter is comparable to the wavelength. Appl Opt. 1991;30:5316–5323. doi: 10.1364/AO.30.005316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Colbeck I, Hardman EJ, Harrison RM. Optical and dynamical properties of fractal clusters of carbonaceous smoke. J Aerosol Sci. 1989;20:765–774. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fikioris JG. Electromagnetic field inside a current-carrying region. J Math Phys. 1965;6:1617–1620. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lakhtakia A. Polarizability dyadics of small chiral ellipsoids. Chem Phys Lett. 1990;174:583–586. [Google Scholar]