Abstract

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is the leading cause of death in patients with refractory epilepsy. SUDEP occurs more commonly during nighttime sleep. The details of why SUDEP occurs at night are not well understood. Understanding why SUDEP occurs at night during sleep might help to better understand why SUDEP occurs at all and hasten development of preventive strategies. Here we aimed to understand circumstances causing seizures that occur during sleep to result in death. Groups of 12 adult male mice were instrumented for EEG, EMG, and EKG recording and subjected to seizure induction via maximal electroshock (MES) during wakefulness, nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Seizure inductions were performed with concomitant EEG, EMG, and EKG recording and breathing assessment via whole body plethysmography. Seizures induced via MES during sleep were associated with more profound respiratory suppression and were more likely to result in death. Despite REM sleep being a time when seizures do not typically occur spontaneously, when seizures were forced to occur during REM sleep, they were invariably fatal in this model. An examination of baseline breathing revealed that mice that died following a seizure had increased baseline respiratory rate variability compared with those that did not die. These data demonstrate that sleep, especially REM sleep, can be a dangerous time for a seizure to occur. These data also demonstrate that there may be baseline respiratory abnormalities that can predict which individuals have higher risk for seizure-induced death.

Keywords: seizure, SUDEP, sleep

epilepsy affects millions of people world-wide (Banerjee et al. 2009). It is estimated that one in 26 people in the United States alone will develop epilepsy in their lifetime (Hesdorffer et al. 2011a). Upwards of 30% of patients with epilepsy develop refractory epilepsy (Schmidt 2009). Refractory epilepsy carries a high risk of death, especially sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), the leading cause of death in these patients (Hesdorffer et al. 2011b). Among neurological conditions, SUDEP is second only to stroke in terms of number of potential years of life lost (Thurman et al. 2014), reflecting the fact that SUDEP tends to occur in young individuals who otherwise would have been able to contribute to society for decades. Thus, SUDEP constitutes a major public health problem.

Retrospective analyses of SUDEP cases has revealed that seizure-induced respiratory and/or cardiac failure is a common etiology for SUDEP (Bateman et al. 2010; Nashef et al. 1996; Ryvlin et al. 2013). In the large multicenter MORTEMUS study of SUDEP cases from epilepsy monitoring units, apnea preceded terminal asystole in all definite SUDEP cases for which there was sufficient data (Ryvlin et al. 2013). It has been suggested that baseline reduction of heart rate variability (Degiorgio et al. 2010; Stein et al. 1994) or prolonged postictal suppression of cortical activity (Bozorgi and Lhatoo 2013; Lhatoo et al. 2010) may be biomarkers that herald an increased likelihood of SUDEP.

Another consistent factor in SUDEP cases is that SUDEP tends to occur at night (Lamberts et al. 2012; Nobili et al. 2011). In the aforementioned MORTEMUS study, almost all of the definite SUDEP cases occurred at night. The majority of these occurred during sleep, with no clear association to one particular sleep state (Ryvlin et al. 2013). The specific mechanisms by which SUDEP occurs at night are unknown. It has been suggested that this could simply be a product of reduced monitoring during the nighttime when patients are supposed to be asleep, and thus resulting in delayed or absent resuscitation efforts (Langan et al. 2000; Nashef et al. 1998). It has also been suggested that this could be due to the patient ending up in the prone position following a nighttime seizure, leading to suffocation from airway obstruction (Tao et al. 2015). There is evidence to suggest that reduced supervision and delayed resuscitation can contribute (Seyal et al. 2013) and that many SUDEP victims are found in the prone position (Liebenthal et al. 2015; Tao et al. 2010); however, there may be other physiological reasons for sleep to be a prime time for SUDEP to occur (Sowers et al. 2013). For instance, there is state-dependent variability in cardiac and respiratory function (Buchanan 2013; Cajochen et al. 1994; Snyder et al. 1964), and sleep state can influence the frequency, severity, and duration of seizures (Bazil and Walczak 1997; Ng and Pavlova 2013). Thus, it follows that if a seizure were to occur during this time of cardio-respiratory instability, it could prove fatal. Therefore, SUDEP may represent a convergence of untoward cardiac and respiratory effects from both sleep and the seizure.

Here we examined whether seizures that occur during different sleep states have differential effect on electrocerebral, cardiac, and respiratory function and mortality. Seizures were induced via maximal electroshock (MES) in adult male mice during different vigilance states with concomitant measurement of electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), electrocardiography (EKG), and breathing via whole-body plethysmography. We found that in this model the vigilance state during which the seizure was induced differentially affected respiratory and electrocerebral function and survival and that baseline respiratory rhythm irregularity predicted risk of seizure-induced death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

All procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University School of Medicine.

Experimental animals.

Adult male (24–32 g) mice from our colony were housed in standard cages in a 12 h light/12 h dark regimen with food and water available ad libitum. Breeding and genotyping of our mouse line, which are on a primarily C57BL/6J background, has been described previously (Buchanan et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2006).

EEG/EMG headmount and EKG electrode implantation.

EEG/EMG headmounts (8201; Pinnacle Technology, Lawrence, KS) were implanted as previously described (Buchanan and Richerson 2010). Briefly, under isoflurane (0.5–2% inh.) anesthesia, the skull was exposed and the headmount was attached to the skull with two 0.1 in. (anterior) and two 0.125 in. (posterior) stainless steel machine screws (000-120; Pinnacle Technology). EMG leads emanating from the posterior portion of the headmount were sutured into the bilateral nuchal muscles ∼1 mm from the midline. Animals were concurrently implanted with EKG leads (MS303-76; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) in the left chest wall and right axilla, and a subcutaneous temperature transponder (IPTT-300; Bio Medic Data Systems, Seaford, DE) was implanted over the scapulae. The base of the headmount, screw heads, and EMG leads were anchored with dental acrylic (Jet Acrylic; Lang Dental, Wheeling, IL), and the skin sutured closed leaving only the headmount socket exposed. Animals received pre- and postoperative analgesia with meloxicam (0.3 mg/kg ip preoperatively; 0.05 mg/kg/day postoperatively in the drinking water for 7 days) and were allowed to recover for 7–10 days before being studied.

Seizure induction with MES.

Animals were acclimated to the recording apparatus for 1 h per day on 3 consecutive days prior to being studied. On the trial day, baseline data were recorded for at least 30 min, and then each mouse received a single electroshock stimulation (50 mA; 0.2 s; 60 Hz sine wave pulses) via ear clip electrodes (modified, toothless, stainless steel alligator clips with saline moistened gauze) attached to a Rodent Shocker (Harvard Apparatus) during the vigilance state of interest. As seen previously, with these stimulus parameters many mice succumbed to the seizure (Buchanan et al. 2014). Seizure severity was assessed by determination of the extension-to-flexion ratio (E/F ratio): length of time the hindlimbs were extended beyond 90° divided by the length of time the hindlimbs were flexed (≤ 90°). Higher E/F ratios correlate with widespread propagation of epileptiform activity (Anderson et al. 1986). E/F ratio determinations were made off-line by post hoc video review. MES thresholds were determined for this mouse strain previously (Buchanan et al. 2014).

EEG/EMG/EKG data acquisition.

EEG, EMG, and EKG data were acquired as described previously (Buchanan and Richerson 2010; Buchanan et al. 2014). Briefly, a preamplifier (8202-SL, Pinnacle Technology) was attached to the implanted headmount, and the animals were introduced to the recording chamber and allowed to acclimate as described. Preamplifier leads were then passed through a commutator (#8204, Pinnacle Technology) and into a conditioning amplifier (model 440 Instrumentation Amplifier; Brownlee Precision, San Jose, CA). EEG and EMG signals were amplified (50,000×), band-pass filtered (0.3–200 Hz for EEG; 10–300 Hz for EMG) and digitized (1,000 samples/s) with an analog-to-digital (A-D) converter (PCI-6221; National Instruments, Austin, TX) in a desktop computer (Dell) and acquired using software custom written in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). EKG signals were passed through a separate conditioning amplifier (Grass LP511 AC; Astro-Med, West Warwick, RI) where they were amplified (20,000×) and band-pass filtered (0.3–300 Hz) and then digitized with the A-D converter as above. Body temperature signals from the implanted telemeter were sampled periodically with a telemetry reader wand (DAS-7007S, Bio Medic Data Systems).

Sleep-wake determination.

Sleep state was assessed on-line in real time prior to delivery of the stimulation. A standard approach based on the EEG/EMG frequency characteristics was used to assign vigilance state (Franken et al. 1998) as follows: Wake - low amplitude, high frequency (7–13 Hz) EEG with high EMG power; Nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep - high amplitude, low frequency (0.5–4 Hz) EEG with moderate to low EMG power and lack of voluntary motor activity; Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep - moderate amplitude, moderate frequency (4.5–8 Hz) EEG with minimal EMG power except for brief bursts and minimal activity correlating with EMG bursts. Electroshocks were delivered when the animals were determined to be in the vigilance state of interest for at least 60 s. Vigilance states were verified off-line post hoc using custom software written in MATLAB. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) power spectra were created with MATLAB for each 10 s epoch of data and used along with EEG and EMG characteristics to verify scoring.

Breathing plethysmography.

For quantification of ventilation the recording chamber was fit with an ultralow pressure/high-sensitivity pressure transducer (DC002NDR5; Honeywell International, Minneapolis, MN). The analog output from the pressure transducer was digitized by the A-D converter (PCI-6221; National Instruments, Austin, TX), displayed on a computer monitor in real time using the acquisition program custom written in MATLAB. A mechanical ventilator (Mini-Vent, Harvard Apparatus) was used to deliver metered breaths (300 μl, 150 breaths/min) to the recording chamber to calibrate the breathing signal. Individual breaths were identified and measured using custom software written in MATLAB to aid in assessment of breathing parameters including respiratory rate (RR), tidal volume (VT), and minute ventilation (VE) as previously described (Hodges et al. 2008; Buchanan et al. 2014). Relative humidity, ambient temperature, body temperature, and atmospheric pressure (obtained from http://www.wunderground.com) were used to calculate VT using standard methods (Buchanan et al. 2014; Drorbaugh and Fenn 1955).

EKG analysis.

Heart rate (HR) and measurements of heart rate variability (HRV) were determined using custom software written in MATLAB and Kubios HRV 2.2 (University of Eastern Finland; http://kubios.uef.fi). HRV indices included the standard deviation of all R-R intervals (SDNN) and the root mean square of the standard deviation of the differences between R-R intervals (RMSSD). These are standard measurements that are good indicators of autonomic function (Stein et al. 1994) and are thought to be predictive of SUDEP risk (Degiorgio et al. 2010; Kalume et al. 2013). The coefficient of variance of the HR was determined with the aid of Microsoft Excel.

Statistics.

Interactions between vigilance state and respiratory and cardiac measures were analyzed for all physiological variables using two-way analysis of variance, paired t-test, or two-tailed t-test assuming unequal variance as appropriate. Survival analyses were conducted with logistic regression. The significance threshold was P < 0.05 for all conditions. Analyses were accomplished using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA), OriginPro 9.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA), and Systat 11.0. Data expressed as x ± y represent means ± SE, unless stated otherwise. All error bars represent SE.

RESULTS

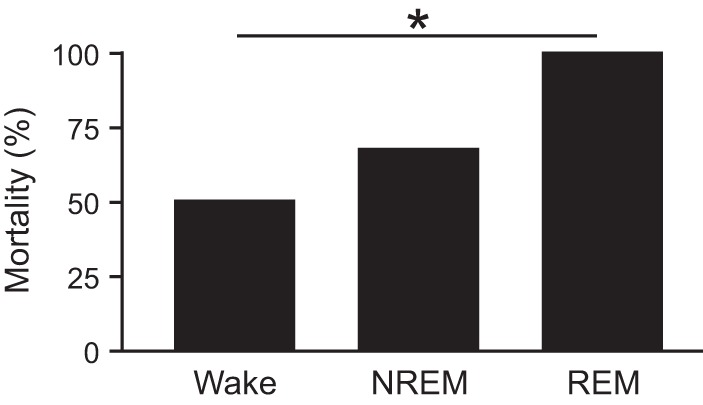

Seizures induced via MES during sleep were more likely to result in death.

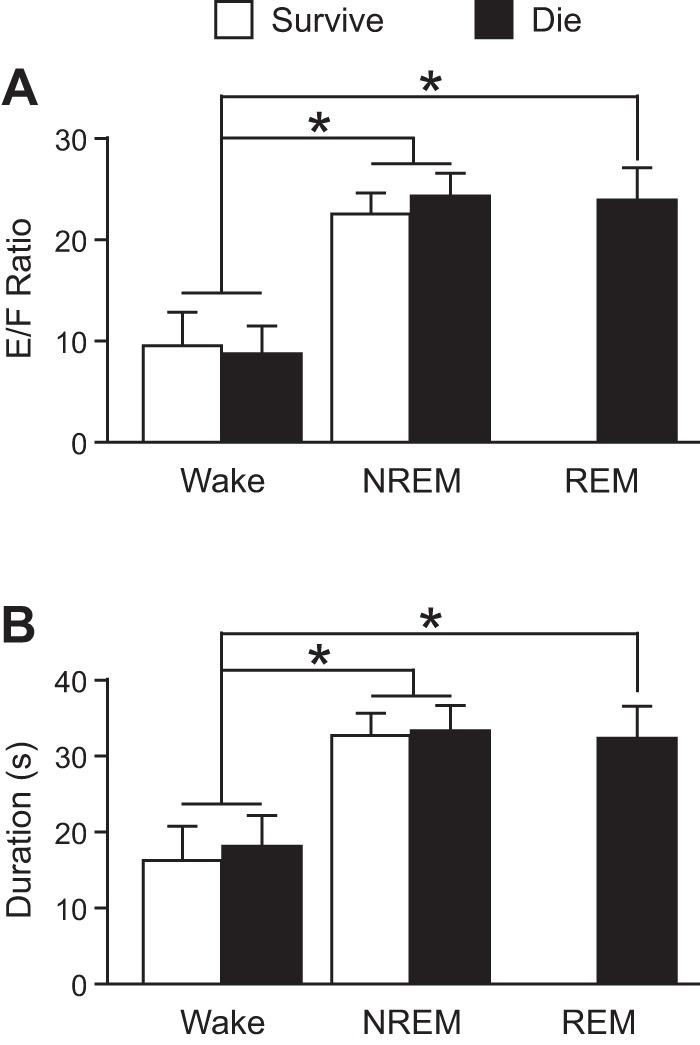

To determine whether the vigilance state during which a seizure occurred had any influence on survival, seizures were induced via MES in separate groups of mice during wakefulness, NREM sleep, and REM sleep (n = 12 per vigilance state). Strikingly, all mice that experienced a seizure that was induced during REM sleep died (Fig. 1). When seizures were induced during NREM sleep 67% of mice died, and 50% died when seizures were induced during wakefulness (Fig. 1). Seizures induced during sleep were more severe compared with those induced during wakefulness with E/F ratios of 23.55 ± 2.23 when induced during NREM and 23.75 ± 2.98 when induced during REM compared with 9.08 ± 2.98 when induced during wakefulness (n = 12 per group; P < 0.05 for NREM or REM compared with wakefulness; Fig. 2A). Seizures induced during sleep were also longer in duration compared with those induced during wakefulness lasting 32.89 ± 3.01 s when induced during NREM and 32.11 ± 3.98 s when induced during REM, but only 17.09 ± 4.13 s when induced during wakefulness (n = 12 per group; P < 0.05 for NREM or REM compared with wakefulness; Fig. 2B). There was no significant difference in severity (P = 0.435) or duration (P = 0.284) between those induced during NREM vs. REM sleep (Fig. 2). There was no significant difference in the severity [E/F ratios: wake (W), 9.47 ± 3.24 survive vs. 8.69 ± 2.72 die, P = 0.337; NREM (N), 22.38 ± 2.04 survive vs. 24.14 ± 2.32 die, P = 0.111] or duration (W, 16.13 ± 4.31 s survive vs. 18.04 ± 3.94 s die, P = 0.221; N, 32.47 ± 2.85 s survive vs. 33.10 ± 3.09 s die, P = 0.364) of seizures between those that survived compared with those that died when seizures were induced during wakefulness or NREM (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Seizures induced via maximal electroshock (MES) during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep are universally fatal. Mortality rates for seizures induced during Wake, nonrapid eye movement (NREM), and REM. n = 12 per sleep state. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

Increased severity and duration of seizures induced via MES during sleep. Severity (A) and duration (B) of seizures induced during Wake, NREM, and REM in mice that survived (white; n = 6, 4, and 0, respectively) and those that died (black; n = 6, 8, and 12, respectively). *P < 0.05. E/F ratio, extension-flexion ratio.

Seizures induced via MES during sleep were more likely to be associated with respiratory suppression.

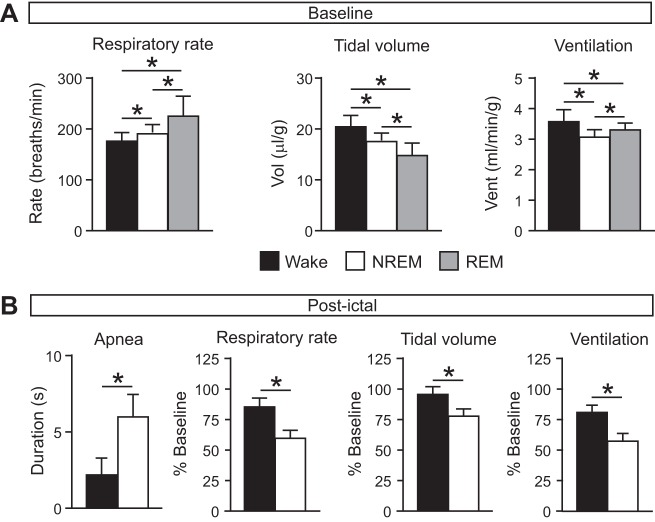

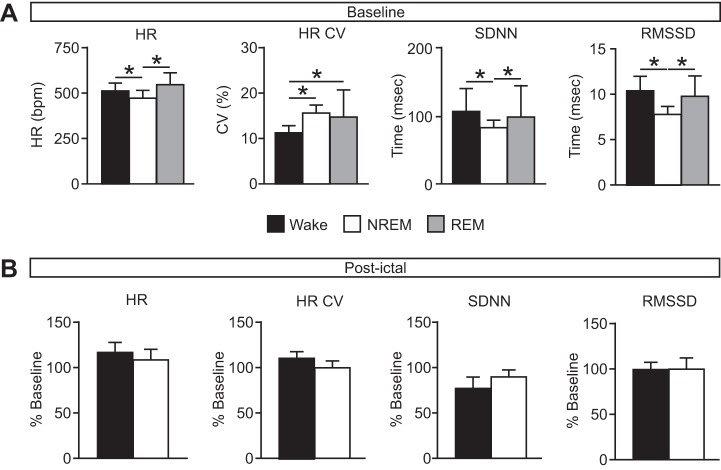

To determine whether the vigilance state during which a seizure occurred had an effect on the respiratory and/or cardiac sequelae of the seizure, respiratory and cardiac function were assessed before, during, and after seizures induced with MES during each vigilance state. At baseline, as expected, there were state-dependent differences in breathing during the different vigilance states, with increased RR (W, 174.80 ± 16.65 breaths/min; N, 189.21 ± 14.53 breaths/min; R, 223.58 ± 39.33 breaths/min; n = 12 per group; P < 0.05 for all comparisons), reduced VT (W, 20.28 ± 2.14 μl/g; N, 17.38 ± 1.36 μl/g; R, 14.66 ± 2.61 μl/g; n = 12 per group; P < 0.05 for all comparisons), and VE (W, 3.55 ± 0.36 ml·min−1·g−1; N, 3.09 ± 0.22 ml·min−1·g−1; R, 3.28 ± 0.20 ml·min−1·g−1; n = 12 per group; P < 0.05 for all comparisons) during NREM and REM sleep compared with wakefulness (Fig. 3A). Similarly, as expected, there was state-dependent variation in cardiac activity at baseline (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 3.

Greater degree of respiratory suppression following seizures induced during NREM sleep. A: baseline respiratory rate (left), tidal volume (middle), and minute ventilation (right) during wake (black), NREM (white), and REM (gray). *P < 0.05. n = 12 for each state. B: postictal apnea (left), respiratory rate (left middle), tidal volume (right middle), and minute ventilation (right) following seizures induced during wake (black) and NREM (white) presented as percentage of baseline. *P < 0.05. n = 6 for Wake; n = 4 for NREM.

Fig. 4.

Minimal effect of seizures induced during different vigilance states on cardiac function. A: baseline heart rate (HR), coefficient of variance of the interheart-beat interval (HR CV), and heart rate variability (SDNN, RMSSD) during wake (black), NREM (white), and REM (gray). HR: wake (W), 508.17 ± 36.61 beats/min; NREM (N), 468.31 ± 37.50 beats/min; REM (R), 520.72 ± 64.67 beats/min; P = 0.272 for W compared with R; HR CV: W, 11.17 ± 1.43%; N, 15.48 ± 1.55%; R, 14.61 ± 5.69%; P = 0.326 for N compared with R; SDNN: W, 105.67 ± 33.23 ms; N, 81.97 ± 10.31 ms; R, 97.40 ± 46.69 ms; P = 0.310 for W compared with R; RMSSD: W, 10.39 ± 1.54 ms; N, 7.74 ± 0.77 ms; R, 9.70 ± 2.16 ms; P = 0.209 for W compared with R. *P < 0.05. n = 12 for each state. B: postictal cardiac measures (as in A) following seizures induced during wake (black) and NREM (white) presented as percentage of baseline. Raw postictal values as follows: HR: W, 588.48 ± 80.91 beats/min; N, 471.26 ± 76.37 beats/min; P = 0.059; HR CV: W, 12.32 ± 2.14%; N, 15.32 ± 2.31%; P = 0.159; SDNN: W, 80.71 ± 23.94 ms; N, 72.91 ± 15.43 ms; P = 0.273; RMSSD: W, 10.18 ± 2.32 ms; N, 7.27 ± 1.86 ms; P = 0.079. n = 6 for Wake; n = 4 for NREM. SDNN, standard deviation of R-R intervals; RMSSD, root mean square of the differences between consecutive R-R intervals.

Consistent with what was demonstrated previously for seizures induced via MES during wakefulness (Buchanan et al. 2014), all seizures were associated with respiratory arrest during the seizure regardless of the vigilance state during which it was induced. Among survivors, seizures induced during NREM sleep caused a longer duration of postictal apnea compared with those induced during wakefulness (W, 2.16 ± 1.08 s, n = 6; N, 5.94 ± 1.47 s, n = 4; P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). When breathing resumed following the postictal respiratory arrest, there was a reduced rate (W, 148.11 ± 21.58 breaths/min, n = 6; N, 111.89 ± 19.69 breaths/min, n = 4; P < 0.05), reduced VT (W, 19.24 ± 1.22 μl/g, n = 6; N, 13.42 ± 1.89 μl/g, n = 4; P < 0.05), and consequently reduced VE (W, 2.85 ± 0.29 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 6; N, 1.76 ± 0.28 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 4; P < 0.05) following seizures induced during NREM sleep compared with those induced during wakefulness (Fig. 3B). There were no significant differences in cardiac measures among the different conditions (Fig. 4B). It should be noted that this assessment could not be performed in mice that died, because breathing did not recover to allow postictal assessment. Thus, this assessment could not be performed for seizures induced during REM sleep since all mice died in this condition.

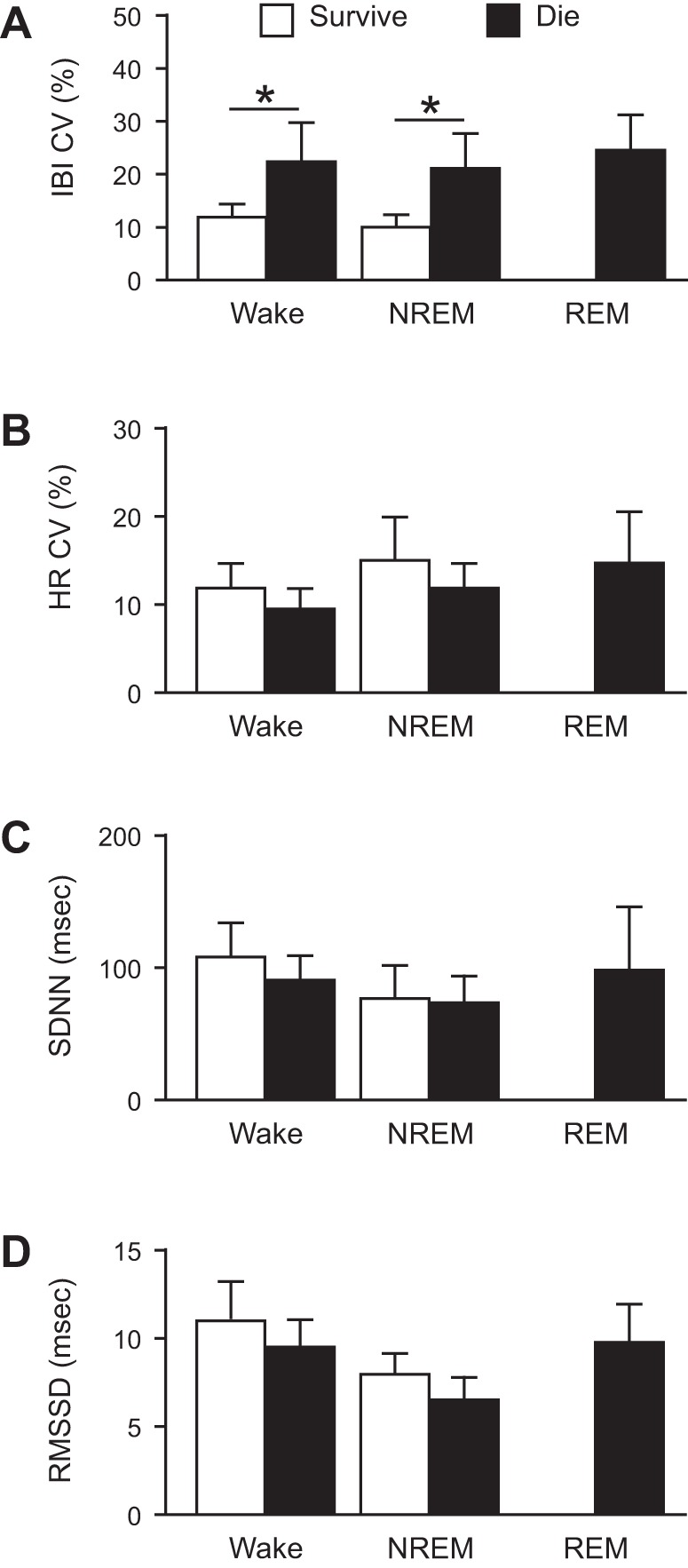

Mice that died following a seizure had increased baseline RR variability.

To determine whether there were any physiological indicators that correlate with survival from a seizure, breathing and cardiac activity were assessed at baseline in all animals, and the data were sorted by survival status. Among seizures induced during a given vigilance state, there was increased respiratory rhythm irregularity in those mice that went on to die from the seizure compared with those that survived the seizure (Fig. 5A). There was a nonsignificant trend toward reduction in HRV in mice that died compared with those that survived when seizures were induced during different vigilance states (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Increased baseline respiratory rhythm variability in mice that ultimately died from an MES-induced seizure. Coefficient of variance of the interbreath interval (IBI CV, A), coefficient of variance of the interheart-beat interval (HR CV, B), and measures of HRV (SDNN, C; RMSSD, D) for mice that survived (white; n = 6, 4, and 0, respectively) and mice that died (black; n = 6, 8, and 12, respectively) from seizures induced by MES during Wake, NREM, or REM. *P < 0.05. Abbreviations as in Fig. 4. IBI CV: W, 11.79 ± 2.72% survive vs. 22.20 ± 7.34% die; N, 9.92 ± 2.44% survive vs. 20.96 ± 6.87% die; R, 24.33 ± 6.77% die; HR CV: W, 11.79 ± 2.72% survive vs. 9.45 ± 2.65% die; N, 14.92 ± 5.06% survive vs. 11.79 ± 3.08% die; R, 14.61 ± 5.69% die; SDNN: W, 107.68 ± 25.19 ms survive vs. 90.03 ± 1.65 ms die; N, 76.06 ± 24.33 ms survive vs. 72.99 ± 22.52 ms die; R, 97.40 ± 46.69 ms die; RMSSD: W, 10.91 ± 2.11 ms survive vs. 9.43 ± 1.58 ms die; N, 7.89 ± 1.22 ms survive vs. 6.46 ± 1.32 ms die; R, 9.70 ± 2.16 ms die.

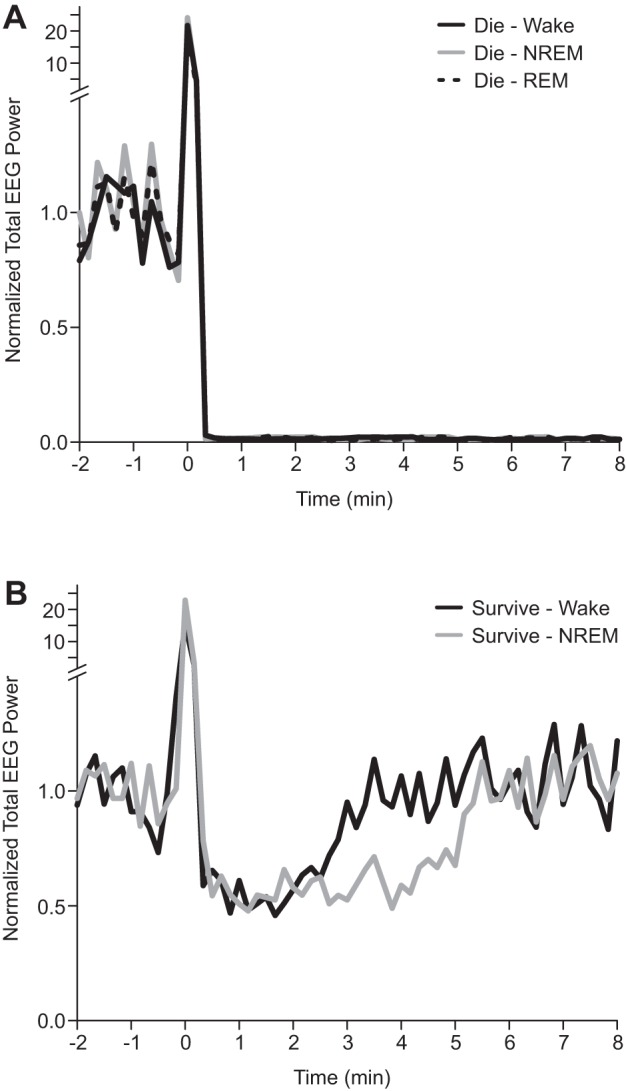

Prolonged EEG suppression following seizures induced during NREM sleep compared wakefulness.

We previously observed reversible suppression of EEG activity following nonfatal seizures induced during wakefulness (Buchanan et al. 2014). To determine whether the vigilance state during which a seizure occurred influenced the duration of the postictal EEG suppression total EEG power was determined with FFT before, during, and after seizures induced via MES during each vigilance state. In all mice that died from the seizure there was immediate and complete suppression of EEG power following the seizure irrespective of the vigilance state during which it was induced (Fig. 6A). Following nonfatal seizures, there was a reduction of EEG power that returned to baseline over some minutes after the end of the seizure. The duration of the suppression was longer for seizures that were induced during NREM sleep compared with those induced during wakefulness (5.19 ± 0.72 min vs. 3.04 ± 0.65 min; P < 0.05; Fig. 6B). The magnitude of the suppression was similar for seizures induced during wakefulness and NREM sleep (Fig. 6B). Since this suppression is seen in mice that survived, it does not seem to contribute to the mechanism of death. However, such alterations in EEG may correlate with reduction in sensitivity to stimulation, and thus could prove to be relevant as postictal recovery strategies are developed.

Fig. 6.

Prolonged suppression of electroencephalography (EEG) activity following nonfatal seizures induced during NREM sleep. Total EEG power between 0.5 and 20 Hz plotted vs. time relative to seizure onset (time 0) in 10 s epochs. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) power is plotted relative to 1 min of baseline EEG during wakefulness prior to seizure induction. Mean data are presented for mice that died (A) following seizures induced during wakefulness (black; n = 6), NREM (gray; n = 8), and REM (dotted; n = 12), and those that survived (B) following seizures induced during wakefulness (black; n = 6) and NREM (gray; n = 4).

DISCUSSION

SUDEP occurs more commonly during sleep, but the specific reason for this has not previously been elucidated. It has been proposed that environmental factors, such as reduced supervision and prone sleeping position, may be the primary cause; however, whether sleep state could be an independent risk factor has not been explored. Here we provide evidence in one animal model that the sleep state during which a seizure occurs can differentially affect respiratory and electrocerebral function following seizures and contribute to mortality. We further show that baseline respiratory rhythm irregularity may predict which animals are more likely to die from a seizure. Finally, we demonstrate that if a seizure occurs during REM sleep, a time when seizure typically will not occur spontaneously, it has a high likelihood of being fatal.

Sleep state differentially influences respiratory consequences of seizures.

It is well known that sleep state influences breathing. Changes in breathing during sleep are due in part to reduction in activity of respiratory motor neurons. Those that are more purely respiratory, such as those controlling the diaphragm, are least affected by sleep states changes. Motor neurons that are typically more susceptible to nonrespiratory influences, such as those involved with regulating upper airway tone and those controlling abdominal and intercostal accessory respiratory muscles, reduce their activity during sleep (Orem et al. 1977; Orem et al. 2002; Orem et al. 1974). Additionally, primary respiratory neurons in the dorsal and ventral respiratory groups governing inspiration and expiration, respectively; the pontine respiratory groups dictating the shape of the respiratory pattern; and the pre-Bötzinger complex, which houses the respiratory pattern generator (Smith et al. 1991) all alter their activity in a sleep-state dependent manner (Douglas 1984; Montandon and Horner 2013; Orem 1980; Orem et al. 1985; Orem et al. 1974). Subtle differences in the integrity of these systems between individuals (Shea and Guz 1992; Shea et al. 1990) may explain why some might be more susceptible to the additional effects of seizure. Whether systematic differences in the function of these systems exist in patients with epilepsy is not known.

Sensitivity of the respiratory system to hypercapnia and hypoxia is reduced during sleep and becomes progressively more decreased as one progresses into deeper stages of NREM sleep and into REM sleep (Bulow 1963; Douglas et al. 1982; Phillipson et al. 1978; Santiago et al. 1984). Thus, if breathing is halted by a seizure during sleep, the accumulated CO2 may not mount a sufficient respiratory response to adequately stimulate breathing and sustain life, owing to the reduced sensitivity to CO2. It may also be true that the accumulation of CO2 may be too large and outside the range to maintain respiratory drive. Similarly, independent of the respiratory effects, the CO2 stimulus may be insufficient to stimulate arousal and restore airway patency as typically occurs with arousal, such as in sleep apnea. This is likely to be exacerbated by reduction of activity and sensitivity of nuclei involved in breathing and sleep-wake regulation such as serotonergic nuclei of the medullary and dorsal raphe (Buchanan and Richerson 2010), respectively, and noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus, among others.

Seizures cause varying degrees of respiratory dysregulation depending on the seizure type and where they originate (Bateman et al. 2008; Blum 2009). Generalized tonic-clonic seizures cause muscles, including those involved in breathing, to contract during the seizure, thus contributing to seizure-induced apnea. There is evidence that seizures can have far reaching effects on brain loci involved in arousal and sleep-wake regulation, largely through inhibition of network connections to these sites (Blumenfeld 2012; Blumenfeld et al. 2004; Englot et al. 2009; Englot et al. 2008; Furman et al. 2015; Gummadavelli et al. 2015; Motelow et al. 2015; Sedigh-Sarvestani et al. 2014a), but may also include brain-stem structures involved in regulation of breathing (Blumenfeld et al. 2009) including 5-HT neurons (Zhan et al. 2016). Recently, it has been shown that seizures initiate spreading depolarization that influences cardiac and respiratory function (Aiba and Noebels 2015). It follows that since breathing patterns are set by vigilance state, a seizure occurring during different vigilance states would differentially affect respiratory function depending on the starting point. Here we found that vigilance state does indeed influence the effect of a seizure on respiratory function.

Implications of abnormal baseline breathing in mice that ultimately died from seizures.

It was somewhat surprising to find that the mice that died from seizures had irregular baseline respiratory rhythms. Though this was a subtle difference, it was consistent and statistically significant. Inspection of the baseline respiratory data from the entire population of animals used in this study revealed that this population of mice displayed a similar mean respiratory rate with similar standard deviation compared with published mouse populations (Friedman et al. 2004; Hodges et al. 2008). However, separating the mice that died from the ones that survived revealed the subtle variation in the coefficient of variance of the respiratory rhythm. This was considered a surprising finding because these mice are not a specific model of hyperexcitability. Therefore, it does not necessarily speak to respiratory instability caused by epilepsy but speaks to a possible naturally occurring respiratory variation that could make a subject more likely to die should they experience a seizure. Given that by definition patients with epilepsy have increased proclivity to having seizures, then identifying respiratory rhythm instability in epilepsy patients could help identify who is at risk for dying from a seizure, or at risk for SUDEP. It will be informative moving forward to determine whether there are similar variances in respiratory rhythms in seizure- and/or “SUDEP-prone” animals models, such as DBA mice (Faingold et al. 2010; Tupal and Faingold 2006) or mouse models of Dravet syndrome (Auerbach et al. 2013; Kalume et al. 2013). Interestingly, at least one of the Dravet models has abnormal sleep architecture (Kalume et al. 2015), but whether there is any association between sleep state and seizure-related death in this model is not known.

Possible mechanisms for REM sleep-related seizure mortality.

Seizures rarely occur during REM sleep in human patients with epilepsy (Ng and Pavlova 2013) or in most animal seizure models (Shouse et al. 2004). However, it has been shown that if there is an alteration in hippocampal theta rhythm, as is seen in the rat tetanus toxic model of epilepsy, seizures occur more commonly during REM sleep (Sedigh-Sarvestani et al. 2014b), though, in the initial report of this phenomenon, increased mortality was not observed (Sedigh-Sarvestani et al. 2014b). In the MES model, a generalized seizure is forced to occur. In our hands this invariably resulted in death when the seizure was forced to occur during REM sleep. Evaluation of the preictal cardiac and respiratory parameters revealed that, as typically occurs during REM in humans and most rodent models (Campen et al. 2002; Friedman et al. 2004; Shea and Guz 1992), there was less regularity of both the respiratory and cardiac rhythms during REM sleep. This suggests that the additional insult of a seizure during this “unstable” period from a cardio-respiratory standpoint overwhelms the system and the animal succumbs to the seizure.

Here we observed similar baseline respiratory rhythm variability in mice that died when seizures were induced during REM sleep as we did for mice that died when seizures were induced during other vigilance states. To the extent that we could assess it in this study, we did not observe a substantial contribution to death from cardiac dysregulation. However, in rats, seizures induced by MES are associated with cardiac instability that recovers over time (Darbin et al. 2003; Darbin et al. 2002; Naritoku et al. 2003). Differential effects of sleep state were not examined in those studies. It is certainly reasonable to consider that the additive physiological insult of seizure and REM sleep pushes the physiological instability of the cardiac as well as respiratory systems above a threshold and leads to mortality. In every instance the immediate cause of death was respiratory arrest, consistent with what has been seen for seizure induced during wakefulness during the daytime in this model (Buchanan et al. 2014).

Limitations of the MES model.

The MES model is a model of seizure induction in an otherwise seizure-naïve brain. Therefore, it is not a model of epilepsy, per se, but it is a good model with which to examine the effects of a single seizure. An advantage of this model is that seizures can be induced at a time, or vigilance state, of the investigator's choosing. In this case, it allowed seizures to be induced in REM sleep, a time when they do not often occur normally, and allowed us to learn that if a seizure occurs during REM sleep it has a high likelihood of being fatal (100% in this study). We have previously used this model to demonstrate differences in the physiological consequences of seizures between different genetic mouse models and now used it to explore sleep state-dependent effects. Given that a single generalized seizure can cause death, data from the MES model are relevant to SUDEP.

Conclusions

Based on population estimates, nearly 1% of Americans live with refractory epilepsy. This figure is likely higher for the world-wide population. These individuals are at high risk for SUDEP. It is widely appreciated that SUDEP occurs more commonly during the nighttime and most likely during sleep. This study demonstrates that sleep state can be an independent risk factor for seizure-associated death in certain populations of mice. Data from this study suggest that the small subset of patients that might have seizures during REM sleep would be at increased risk for SUDEP. These data also suggest that individuals with epilepsy who have somewhat irregular breathing at baseline may be at increased risk for SUDEP. It will be important moving forward to continue to understand factors that ordinarily prevent seizures from occurring during REM sleep and to look for possible respiratory biomarkers, such as irregular respiratory rhythm, in human patients with epilepsy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by The Christopher Donalty and Kyle Coggins Memorial SUDEP Research Fund from Citizens United for Research on Epilepsy (CURE; G. F. Buchanan) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants 5K08NS-069667 (G. F. Buchanan) and TL1 TR-000151 (M. A. Hajek). Dr. Buchanan is also supported by the Beth and Nathan Tross Epilepsy Research Fund. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under Award Number TL1 TR-00151. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the view of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.A.H. and G.F.B. performed experiments; M.A.H. and G.F.B. analyzed data; M.A.H. and G.F.B. interpreted results of experiments; M.A.H. and G.F.B. prepared figures; M.A.H. and G.F.B. drafted manuscript; M.A.H. and G.F.B. edited and revised manuscript; M.A.H. and G.F.B. approved final version of manuscript; G.F.B. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- Aiba I, Noebels JL. Spreading depolarization in the brainstem mediates sudden cardiorespiratory arrest in mouse SUDEP models. Sci Transl Med 7: 282ra46, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Howard RA, Woodbury DM. Correlation between effects of acute acetazolamide administration to mice on electroshock seizure threshold and maximal electroshock seizure pattern, and on carbonic anhydrase activity in subcellular fractions of brain. Epilepsia 27: 504–509, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach DS, Jones J, Clawson BC, Offord J, Lenk GM, Ogiwara I, Yamakawa K, Meisler MH, Parent JM, Isom LL. Altered cardiac electrophysiology and SUDEP in a model of Dravet syndrome. PLoS One 8: e77843, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee PN, Filippi D, Allen HW. The descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy-a review. Epilepsy Res 85: 31–45, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman LM, Li CS, Seyal M. Ictal hypoxemia in localization-related epilepsy: analysis of incidence, severity and risk factors. Brain 131: 3239–3245, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman LM, Spitz M, Seyal M. Ictal hypoventilation contributes to cardiac arrhythmia and SUDEP: report on two deaths in video-EEG-monitored patients. Epilepsia 51: 916–920, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazil CW, Walczak TS. Effects of sleep and sleep stage on epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia 38: 56–62, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum AS. Respiratory physiology of seizures. J Clin Neurophysiol 26: 309–315, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H. Impaired consciousness in epilepsy. Lancet Neurol 11: 814–826, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, McNally KA, Vanderhill SD, Paige AL, Chung R, Davis K, Norden AD, Stokking R, Studholme C, Novotny EJ Jr, Zubal IG, Spencer SS. Positive and negative network correlations in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cereb Cortex 14: 892–902, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld H, Varghese GI, Purcaro MJ, Motelow JE, Enev M, McNally KA, Levin AR, Hirsch LJ, Tikofsky R, Zubal IG, Paige AL, Spencer SS. Cortical and subcortical networks in human secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Brain 132: 999–1012, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozorgi A, Lhatoo SD. Seizures, cerebral shutdown, and SUDEP. Epilepsy Curr 13: 236–240, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan GF. Timing, sleep, and respiration in health and disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 119: 191–219, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan GF, Murray NM, Hajek MA, Richerson GB. Serotonin neurones have anti-convulsant effects and reduce seizure-induced mortality. J Physiol 592: 4395–4410, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan GF, Richerson GB. Central serotonin neurons are required for arousal to CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 16354–16359, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulow K. Respiration and wakefulness in man. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 59: 1–110, 1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajochen C, Pischke J, Aeschbach D, Borbely AA. Heart rate dynamics during human sleep. Physiol Behav 55: 769–774, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen MJ, Tagaito Y, Jenkins TP, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, O'Donnell CP. Phenotypic differences in the hemodynamic response during REM sleep in six strains of inbred mice. Physiol Genomics 11: 227–234, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbin O, Casebeer D, Naritoku DK. Effects of seizure severity and seizure repetition on postictal cardiac arrhythmia following maximal electroshock. Exp Neurol 181: 327–331, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbin O, Casebeer DJ, Naritoku DK. Cardiac dysrhythmia associated with the immediate postictal state after maximal electroshock in freely moving rat. Epilepsia 43: 336–341, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degiorgio CM, Miller P, Meymandi S, Chin A, Epps J, Gordon S, Gornbein J, Harper RM. RMSSD, a measure of vagus-mediated heart rate variability, is associated with risk factors for SUDEP: the SUDEP-7 Inventory. Epilepsy Behav 19: 78–81, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas NJ. Control of breathing during sleep. Clin Sci (Lond) 67: 465–471, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas NJ, White DP, Weil JV, Pickett CK, Zwillich CW. Hypercapnic ventilatory response in sleeping adults. Am Rev Respir Dis 126: 758–762, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drorbaugh JE, Fenn WO. A barometric method for measuring ventilation in newborn infants. Pediatrics 16: 81–87, 1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Mishra AM, Mansuripur PK, Herman P, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Remote effects of focal hippocampal seizures on the rat neocortex. J Neurosci 28: 9066–9081, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englot DJ, Modi B, Mishra AM, DeSalvo M, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Cortical deactivation induced by subcortical network dysfunction in limbic seizures. J Neurosci 29: 13006–13018, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL, Randall M, Tupal S. DBA/1 mice exhibit chronic susceptibility to audiogenic seizures followed by sudden death associated with respiratory arrest. Epilepsy Behav 17: 436–440, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken P, Malafosse A, Tafti M. Genetic variation in EEG activity during sleep in inbred mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 275: R1127–R1137, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L, Haines A, Klann K, Gallaugher L, Salibra L, Han F, Strohl KP. Ventilatory behavior during sleep among A/J and C57BL/6J mouse strains. J Appl Physiol 97: 1787–1795, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman M, Zhan Q, McCafferty C, Lerner BA, Motelow JE, Meng J, Ma C, Buchanan GF, Witten IB, Deisseroth K, Cardin JA, Blumenfeld H. Optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic brainstem neurons during focal limbic seizures: Effects on cortical physiology. Epilepsia 56: e198–e202, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummadavelli A, Motelow JE, Smith N, Zhan Q, Schiff ND, Blumenfeld H. Thalamic stimulation to improve level of consciousness after seizures: evaluation of electrophysiology and behavior. Epilepsia 56: 114–124, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Benn EK, Katri N, Cascino G, Hauser WA. Estimating risk for developing epilepsy: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology 76: 23–27, 2011a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesdorffer DC, Tomson T, Benn E, Sander JW, Nilsson L, Langan Y, Walczak TS, Beghi E, Brodie MJ, Hauser A. Combined analysis of risk factors for SUDEP. Epilepsia 52: 1150–1159, 2011b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges MR, Tattersall GJ, Harris MB, McEvoy SD, Richerson DN, Deneris ES, Johnson RL, Chen ZF, Richerson GB. Defects in breathing and thermoregulation in mice with near-complete absence of central serotonin neurons. J Neurosci 28: 2495–2505, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalume F, Oakley JC, Westenbroek RE, Gile J, de la Iglesia HO, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Sleep impairment and reduced interneuron excitability in a mouse model of Dravet Syndrome. Neurobiol Dis 77: 141–154, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalume F, Westenbroek RE, Cheah CS, Yu FH, Oakley JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Sudden unexpected death in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. J Clin Invest 123: 1798–1808, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberts RJ, Thijs RD, Laffan A, Langan Y, Sander JW. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: people with nocturnal seizures may be at highest risk. Epilepsia 53: 253–257, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langan Y, Nashef L, Sander JW. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: a series of witnessed deaths. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 68: 211–213, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhatoo SD, Faulkner HJ, Dembny K, Trippick K, Johnson C, Bird JM. An electroclinical case-control study of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Ann Neurol 68: 787–796, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebenthal JA, Wu S, Rose S, Ebersole JS, Tao JX. Association of prone position with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Neurology 84: 703–709, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montandon G, Horner RL. State-dependent contribution of the hyperpolarization-activated Na+/K+ and persistent Na+ currents to respiratory rhythmogenesis in vivo. J Neurosci 33: 8716–8728, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motelow JE, Li W, Zhan Q, Mishra AM, Sachdev RN, Liu G, Gummadavelli A, Zayyad Z, Lee HS, Chu V, Andrews JP, Englot DJ, Herman P, Sanganahalli BG, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Decreased subcortical cholinergic arousal in focal seizures. Neuron 85: 561–572, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naritoku DK, Casebeer DJ, Darbin O. Effects of seizure repetition on postictal and interictal neurocardiac regulation in the rat. Epilepsia 44: 912–916, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashef L, Garner S, Sander JW, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. Circumstances of death in sudden death in epilepsy: interviews of bereaved relatives. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 64: 349–352, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashef L, Walker F, Allen P, Sander JW, Shorvon SD, Fish DR. Apnoea and bradycardia during epileptic seizures: relation to sudden death in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 60: 297–300, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M, Pavlova M. Why are seizures rare in rapid eye movement sleep? Review of the frequency of seizures in different sleep stages. Epilepsy Res Treat 2013: 932790, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobili L, Proserpio P, Rubboli G, Montano N, Didato G, Tassinari CA. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 15: 237–246, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem J. Neural mechanisms of respiration in REM sleep. Sleep 3: 251–252, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem J, Lovering AT, Dunin-Barkowski W, Vidruk EH. Tonic activity in the respiratory system in wakefulness, NREM and REM sleep. Sleep 25: 488–496, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem J, Montplaisir J, Dement WC. Changes in the activity of respiratory neurons during sleep. Brain Res 82: 309–315, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem J, Netick A, Dement WC. Increased upper airway resistance to breathing during sleep in the cat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 43: 14–22, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem J, Osorio I, Brooks E, Dick T. Activity of respiratory neurons during NREM sleep. J Neurophysiol 54: 1144–1156, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson EA, Sullivan CE, Read DJ, Murphy E, Kozar LF. Ventilatory and waking responses to hypoxia in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exercise Physiol 44: 512–520, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryvlin P, Nashef L, Lhatoo SD, Bateman LM, Bird J, Bleasel A, Boon P, Crespel A, Dworetzky BA, Hogenhaven H, Lerche H, Maillard L, Malter MP, Marchal C, Murthy JM, Nitsche M, Pataraia E, Rabben T, Rheims S, Sadzot B, Schulze-Bonhage A, Seyal M, So EL, Spitz M, Szucs A, Tan M, Tao JX, Tomson T. Incidence and mechanisms of cardiorespiratory arrests in epilepsy monitoring units (MORTEMUS): a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 12: 966–977, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago TV, Scardella AT, Edelman NH. Determinants of the ventilatory responses to hypoxia during sleep. Am Rev Respir Dis 130: 179–182, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D. Drug treatment of epilepsy: options and limitations. Epilepsy Behav 15: 56–65, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedigh-Sarvestani M, Blumenfeld H, Loddenkemper T, Bateman LM. Seizures and brain regulatory systems: consciousness, sleep, and autonomic systems. J Clin Neurophysiol 32: 188–193, 2014a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedigh-Sarvestani M, Thuku GI, Sunderam S, Parkar A, Weinstein SL, Schiff SJ, Gluckman BJ. Rapid eye movement sleep and hippocampal theta oscillations precede seizure onset in the tetanus toxin model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 34: 1105–1114, 2014b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyal M, Bateman LM, Li CS. Impact of periictal interventions on respiratory dysfunction, postictal EEG suppression, and postictal immobility. Epilepsia 54: 377–382, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea SA, Guz A. Personnalite ventilatoire–an overview. Respir Physiol 87: 275–291, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea SA, Horner RL, Benchetrit G, Guz A. The persistence of a respiratory ‘personality’ into stage IV sleep in man. Respir Physiol 80: 33–44, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shouse MN, Scordato JC, Farber PR. Sleep and arousal mechanisms in experimental epilepsy: epileptic components of NREM and antiepileptic components of REM sleep. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 10: 117–121, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Botzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 254: 726–729, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder F, Hobson J, Morrison D, Goldfrank F. Changes in respiration, heart rate, and systolic blood pressure in human sleep. J Appl Physiol 19: 417–422, 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers LP, Massey CA, Gehlbach BK, Granner MA, Richerson GB. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: fatal post-ictal respiratory and arousal mechanisms. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 189: 315–323, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PK, Bosner MS, Kleiger RE, Conger BM. Heart rate variability: a measure of cardiac autonomic tone. Am Heart J 127: 1376–1381, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao JX, Qian S, Baldwin M, Chen XJ, Rose S, Ebersole SH, Ebersole JS. SUDEP, suspected positional airway obstruction, and hypoventilation in postictal coma. Epilepsia 51: 2344–2347, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao JX, Sandra R, Wu S, Ebersole JS. Should the “Back to Sleep” campaign be advocated for SUDEP prevention? Epilepsy Behav 45: 79–80, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman DJ, Hesdorffer DC, French JA. Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: assessing the public health burden. Epilepsia 55: 1479–1485, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupal S, Faingold CL. Evidence supporting a role of serotonin in modulation of sudden death induced by seizures in DBA/2 mice. Epilepsia 47: 21–26, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Buchanan GF, Motelow JE, Andrews J, Vitkovskiy P, Chen WC, Serout F, Gummadavelli A, Kundishora A, Furman M, Li W, Bo X, Richerson GB, Blumenfeld H. Impaired serotonergic brainstem function during and following seizures. J Neurosci 36: 2711–2722, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZQ, Scott M, Chiechio S, Wang JS, Renner KJ, Gereau RW, Johnson RL, Deneris ES, Chen ZF. Lmx1b is required for maintenance of central serotonergic neurons and mice lacking central serotonergic system exhibit normal locomotor activity. J Neurosci 26: 12781–12788, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]