Abstract

Firing patterns differ between subpopulations of vestibular primary afferent neurons. The role of sodium (NaV) channels in this diversity has not been investigated because NaV currents in rodent vestibular ganglion neurons (VGNs) were reported to be homogeneous, with the voltage dependence and tetrodotoxin (TTX) sensitivity of most neuronal NaV channels. RT-PCR experiments, however, indicated expression of diverse NaV channel subunits in the vestibular ganglion, motivating a closer look. Whole cell recordings from acutely dissociated postnatal VGNs confirmed that nearly all neurons expressed NaV currents that are TTX-sensitive and have activation midpoints between −30 and −40 mV. In addition, however, many VGNs expressed one of two other NaV currents. Some VGNs had a small current with properties consistent with NaV1.5 channels: low TTX sensitivity, sensitivity to divalent cation block, and a relatively negative voltage range, and some VGNs showed NaV1.5-like immunoreactivity. Other VGNs had a current with the properties of NaV1.8 channels: high TTX resistance, slow time course, and a relatively depolarized voltage range. In two NaV1.8 reporter lines, subsets of VGNs were labeled. VGNs with NaV1.8-like TTX-resistant current also differed from other VGNs in the voltage dependence of their TTX-sensitive currents and in the voltage threshold for spiking and action potential shape. Regulated expression of NaV channels in primary afferent neurons is likely to selectively affect firing properties that contribute to the encoding of vestibular stimuli.

Keywords: vestibular ganglion, vestibular afferent, sodium channel, action potential, NaV1.8, NaV1.5, tetrodotoxin

the vestibular organs of the inner ear sense head orientation and motion, sending signals to the brain that drive powerful ocular, autonomic, and postural reflexes, contribute to our sense of heading, and support learning of complex tasks such as dancing (reviewed in Angelaki and Cullen 2008; Goldberg et al. 2012). Normally, we are unaware of these functions, but their significance is revealed by the vertigo, blurred vision, and disequilibrium of vestibular disorders.

Signals from vestibular hair cells are conveyed to the brainstem and cerebellum by the processes of bipolar vestibular ganglion neurons (VGNs). VGNs that contact the distinct central and peripheral zones of the vestibular sensory epithelia differ in such key features as regularity of spiking, response dynamics, expression of calcium-binding proteins, axonal diameter and conduction velocity, and central projections (reviewed in Goldberg 2000; Lysakowski and Goldberg 2004; Eatock and Songer 2011). Variation in the mechanosensory hair cells also contributes to afferent diversity: type I and type II vestibular hair cells synapse with, respectively, calyceal and bouton afferent terminals, and vestibular afferents are either calyx-only, bouton-only, or, if they contact both types of hair cell, dimorphic.

Mammalian vestibular afferents are remarkable for their high firing rates and bimodal distribution of spike regularity, either highly regular or highly irregular. Evidence from isolated VGNs suggests that the irregular spike timing of central-zone afferents depends in part on afferent expression of low-voltage-activated K (KLV) channels (Iwasaki et al. 2008; Kalluri et al. 2010). Voltage-gated calcium (CaV) channels and Ca2+-gated K channels also vary across VGN populations (Limón et al. 2005). Because neuronal firing patterns are affected by differential expression of voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV) subunits (Bean 2007), we have examined NaV channel expression by VGNs. The pore-forming α-subunits of NaV channels are categorized according to their sensitivity to block by tetrodotoxin (TTX). Most α-subunits are TTX sensitive, with half-blocking doses of ∼10 nM, but NaV1.5 channels (TTX-insensitive) require over 10-fold larger doses, and NaV1.8 and NaV1.9 channels (TTX-resistant) are not blocked even by 1 μM TTX. Previous studies on VGNs have reported only TTX-sensitive NaV currents (Chabbert et al. 1997; Risner and Holt 2006). Here we show that the rat vestibular ganglion expresses mRNA for TTX-sensitive NaV α-subunits, as expected, but also NaV1.5, 1.8, and 1.9 subunits. NaV1.5 channels are strongly expressed in cardiac muscle (Gellens et al. 1992), where their current drives the upstroke of the cardiac action potential. The NaV1.8 current was first described as a slow current specific to small peripheral nociceptive neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and trigeminal ganglia (Akopian et al. 1996; Sangameswaran et al. 1996). We show that many early postnatal VGNs express NaV1.5-like or NaV1.8-like current in addition to TTX-sensitive current and that the TTX-sensitive current also differs between VGNs. The expression of different complements of NaV channels by VGN subpopulations is likely to contribute to spiking heterogeneity that serves vestibular encoding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals were handled in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all procedures were approved by the animal care committee at Baylor College of Medicine (RT-PCR), the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (physiology and fixation of tissue from reporter mice), and the University of Illinois at Chicago (immunocytochemistry). Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified.

RT-PCR

Long-Evans rats, postnatal day (P) 1 or P21, were anesthetized and decapitated and the temporal bones were placed in our standard dissection and bath solution, “modified L-15” (Table 1): chilled, oxygenated Leibovitz-15 medium supplemented with 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, ∼325 mmol/kg. The superior division of the vestibular ganglion, which innervates the utricle, lateral, and anterior semicircular canals and part of the saccule, was dissected out bilaterally and placed in RNase/DNase-free tubes. Excess liquid was removed and the tissue samples were placed on dry ice. The methods are identical to those described for utricular maculae and cristae in Wooltorton et al. (2007). Briefly, we isolated RNA from one ganglion at a time with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The RNA was reverse-transcribed to complementary (c) DNA with the Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (BD Biosystems, Palo Alto, CA) with Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase and random hexamer primers. We controlled for genomic DNA contamination by designing primers to span intron-exon boundaries; homogenizing the tissue to break up genomic DNA; using RNeasy columns, which contain a silica membrane that eliminates most DNA; and treating the column with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen) for 30 min to remove residual DNA. As the “negative RT” controls, for each primer set and tissue type we substituted water for the reverse transcriptase. No bands were detected on agarose gels with any primer set tested in these control samples (data not shown).

Table 1.

External and internal solutions

| Solution |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

External |

||||||||||

| NaCl | NMDG | KCl | CsCl | MgCl2 | TEACl | 4-AP | CaCl2 | HEPES | d-Glucose | |

| Cs+ external | 80* | 0 | 0 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| K+ external | 100 | 0 | 5.4 | 0 | 2.5 | 50 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| NMDG+ external | 0 | 80 | 0 | 5.4 | 2.5 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Modified L-15 | 138† | 0 | 5.3 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 5 | 0 |

|

Internal |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | Na2-Creatine Phosphate | KCl | K2SO4 | CsCl | Mg2+ | ATP | LiGTP | Na-cAMP | EGTA | CaCl2 | HEPES | |

| Cs+ internal | 0 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 148* | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5 or 10 | 0.8 | 5 |

| K+ internal | 5 | 5 | 135 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5 or 10 | 0.8 | 5 |

| Perforated patch | 0 | 0 | 25 | 75 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.1 | 5 |

Concentrations in mM. Dissections were done in modified L-15. Most voltage-clamp recordings were done with Cs+ internal and Cs+ external solutions. Current-clamp recordings of spiking were done with K+ internal and modified L-15. Osmolality was ∼325 mol/kgH2O for external solutions except for NMDG+ external (315 mol/kgH2O) and ∼315 mol/kgH2O for internal solutions except for the perforated patch solution (270 mol/kgH2O). pH was adjusted to 7.3–7.4 by adding KOH to K+ internal (∼17 mM), CsOH to Cs+ internal (∼17 mM), and NaOH to external solutions (∼4 mM), except for external solutions containing 4-AP or NMDG+, which were titrated to pH 7.3–7.4 with HCl. The free internal Ca2+ concentration for 800 μM Ca2+ and 5 mM EGTA was calculated as 20 nM (MaxChelator WEBMAXC software, http://maxchelator.stanford.edu/).

In some early experiments on the voltage dependence and tetrodotoxin (TTX) sensitivity of total NaV current, internal CsCl was 130 mM and external NaCl was 65 mM. Inward Na+ currents were correspondingly smaller in those cells but no other differences were noted. These data were not included in estimates of reversal potential.

L-15 also contains 1.34 mM Na2HPO4 and 5 mM Na-pyruvate. See http://www.lifetechnologies.com/us/en/home/technical-resources/media-formulation.80.html.

PCR was done on a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research, Reno, NV) with the TAQ enzyme (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), the primer sets (IDT, Coralville, IA), and the PCR protocol described in Wooltorton et al. (2007). PCR products were resolved on 1.2% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide.

The PCR product for each primer set was sequenced at least once; sequenced products for NaV1.1–1.7 and β-subunits were from the utricular macula, as reported previously (Wooltorton et al. 2007). NaV1.8 and NaV1.9 products, which were not present in the macula, were sequenced from vestibular ganglia (SeqWright, Houston, TX). Each primer set was tested on ganglion tissue multiple times. For all but three primer sets (NaV1.7, 1.8, and 1.9), we simultaneously tested for expression in standard tissues (brain, heart, or skeletal muscle), as a control for primer quality. NaV1.7, 1.8, and 1.9 are weakly expressed if at all in these standard tissues.

Cell Preparation for Physiology

VGNs were isolated from Long-Evans rat pups. The superior compartment of the vestibular ganglion was dissected out of the isolated temporal bone and placed in modified L-15 (Table 1). The ganglion tissue was incubated in 0.25% trypsin and 0.05% collagenase for 30 min at 37°C and then dissociated by gentle trituration onto glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA). The glass was uncoated for acute preparations and coated with poly-d-lysine for overnight cultures.

Usually, VGNs were dissociated from P1–P8 rat pups, allowed to settle at room temperature (20–25°C), and recorded from between 1 and 7 h posttrituration. In a small number of experiments, dissociated VGNs from P1–P11 rats were incubated in culture medium in 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C for ∼20 h. The culture medium was serum-free minimal essential medium (MEM) with Glutamax (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), supplemented with 10 mM HEPES and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). Data from overnight-cultured neurons are excluded from analysis except for the quantitative characterization of their TTX-sensitive NaV currents.

Recording Solutions

During recording sessions, cells were bathed in preoxygenated L-15 medium. The recorded cell was locally superfused, usually with “Cs+ external” solution (Table 1), which minimized K+ currents by substituting Cs+ for K+ and 50–75 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA, a K channel blocker) for equivalent Na+. Replacing external Na+ with TEA+ also reduced total NaV current and series resistance voltage errors. Ca2+ currents were minimized by substituting Mg2+, a Ca channel blocker, for Ca2+; only trace Ca2+ was present.

For current-clamp studies, solutions were more physiological. The external solution was modified L-15 and the internal solution was “K+ internal” (Table 1). After recording in current-clamp mode, we switched to voltage-clamp mode to characterize the NaV currents, changing at the same time from modified L-15 to “K+ external” solution containing TEA and 4-AP to block KV currents.

In several recordings, we used the perforated patch method to preserve the intracellular milieu (Horn and Marty 1988). The pore-forming antifungal drug (amphotericin B, 200 μg/ml) was added to an internal solution containing K2SO4 and KCl (Table 1).

Whole Cell Recordings

Cells were visualized at ×600 on an inverted microscope equipped with Nomarski optics (IMT-2; Olympus, Lake Success, NY). We chose round cells with diameters >10 μm (range 14–30 μm, most 18–24 μm) and sometimes partly covered by remnants of the enveloping satellite cells. Almost all of these cells had large total NaV currents (peak values >2 nA), consistent with their being VGNs. These diameters are within the range reported by Limón et al. (2005) for VGNs from P7–P10 rats, but smaller on average, probably because our recordings were from a younger age range (P1–P8). The mean membrane capacitance was 15.2 ± 0.4 pF (n = 239), similar to the mean values we obtained previously for P1–P7 rat VGNs with either sustained or transient firing patterns (Kalluri et al. 2010). Kalluri et al. (2010) found that in the second postnatal week, VGNs that fired transiently were larger than VGNs that fired tonically. Thus, in our sample, some neurons have not reached their mature sizes.

Data were acquired with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier, Digidata 1440A digitizer, and pClamp 10 software (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with low-pass Bessel filtering set at 10 kHz and sampling interval set at 10 μs. Electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass to resistances of 1–4 MΩ in our solutions and coated with a silicone elastomer (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI) to reduce electrode capacitance. Voltages were corrected for a liquid junction potential between 5 and 6 mV, calculated for each solution with JPCalc software (Barry 1994) in pClamp10.

To document the incidence of each type of NaV current, we included all VGNs for which NaV currents could be clearly identified based on their kinetics and voltage dependence. For analyses of voltage-dependent properties and current-clamp behavior, cells were accepted if one of the following criteria was met: input resistance ≥0.5 GΩ; a giga-ohm initial seal with a smooth rupture; and a resting potential of at least −58 mV. For the VGNs analyzed for voltage-dependent properties and voltage responses in current clamp, seal resistances exceeded 1 GΩ and series resistance, RS, ranged from 4 to 14 MΩ before electronic compensation. For ruptured-patch recordings, RS was compensated electronically, usually by 80–90%, and the average residual RS was 1.6 ± 0.1 MΩ (n = 198). For analysis of the relatively large total NaV current, we reduced residual RS to 1 MΩ or less to minimize voltage-clamp errors. The mean clamp rise time, τclamp = [Rs × Cm × (1-prediction)], where “prediction” is a fraction set with the amplifier, was 54 ± 2 μs (n = 190). Note also that in external solutions for voltage clamp (Table 1), replacement of one-third to one-half of Na+ by the K channel blocker TEA+ reduced NaV current and series resistance voltage errors. The perforated-patch recordings (see above) had, as is typical, higher Rs values (mean: 29 ± 4.2 MΩ, n = 11, compensated by 50–85% to 5–15 MΩ), and were not used to measure kinetics or activation.

The holding potential (VH) in voltage-clamp mode was −70 mV. Most recordings were at room temperature (range 20–25°C, mean 23.9 ± 0.3°C, n = 130), because fast NaV currents are difficult to voltage clamp and characterize at body temperature. For some recordings (indicated), we heated the bath to 37°C with a heated platform and temperature controller (TC-344B; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Note that VGNs exhibit similar firing pattern categories (“transient” vs. “sustained”) at room and body temperatures (Kalluri et al. 2010).

Pharmacology

Frozen stock solutions of TTX (2 mM or 200 μM in distilled water) were thawed and added to 10 ml of external solution to make the specified concentrations on the day of the experiment. Drugs were applied via controlled local perfusion (Valvelink 8; AutoMate Scientific, Berkeley, CA). Multiple lines were merged at a manifold that flowed into a single tip (∼3-cm long, 250-μm diameter). This dead volume provided a temporal separation between any transient mechanical artifacts induced by line switching and the onset of the drug effect. Perfusion of control solution before the test solution provided an additional control for flow effects. To visualize flow, we added 2 μl of latex beads (0.46-μm mean particle size) to 10 ml of the control and test solutions. Cells were confirmed to be in the path of bead movement and the flow was adjusted to a gentle but steady rate. Wash-in and wash-out of the drug were tracked by a protocol that applied a test voltage step at 10-s intervals. Recordings were analyzed only for cells with stable Rs values in both control and drug solutions. Many cells also provided stable recordings after wash-out of the drug.

Analysis

Analysis was performed in Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) and Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices). Figures were prepared with Origin software (versions 8–15; OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Means ± SE are presented. The voltage protocol comprised, in sequence, a 25- to 80-ms hyperpolarizing prepulse (from VH to −120, −125, or −130 mV) to relieve channel inactivation; a test step of iterated voltage (duration determined by the time course of the current under study, voltage iterated from −125 mV to +30 mV), and a brief tail step at a constant voltage (stepping from the test step to −15, −20, or −30 mV). The voltage dependence of activation and inactivation was analyzed only when Rs voltage error was <5 mV at peak current and τclamp was <100 μs. For the comparatively small TTX-insensitive and TTX-resistant currents, Rs voltage errors were typically <3 mV and were not corrected post hoc.

Activation curves of conductance, g, vs. voltage, V, were generated by plotting the peak current (I) against step voltage, fitting the linear upper region of the V- or U-shaped I-V curve (typically between 0 and +30 mV) to find the reversal potential (Erev) and then dividing the peak current by the driving force (V-Erev) to obtain g. The activation curves were fit by a Boltzmann function:

| (1) |

where gmax is maximum conductance, Vact is voltage of half-maximal activation, and s is the slope factor. Inactivation curves were generated by plotting the peak current produced by a test pulse (to −30, −20, or −10 mV) against the iterated prepulse voltage and fitting with a Boltzmann function:

| (2) |

with Vinact the voltage of half-maximal inactivation.

We fit drug dose-response curves with the Hill equation with Hill coefficient of 1:

| (3) |

where y is the fraction of channels blocked by drug. This equation assumes simple single-site block with an excess of drug relative to sodium channels and no conductance in the blocked state. It is successful at approximating TTX dose-response relations for NaV channels (e.g., Ritchie 1979; Du et al. 2009). Rearranging the Hill equation allows us to calculate the dissociation constant (Kd) from the block at a single drug dose:

| (4) |

For TTX block of total current in cells with both TTX-sensitive and TTX-insensitive currents, we fit the dose-response relation with:

| (5) |

where Kd1 and Kd2 are the dissociation constants for TTX binding of the two components, and A and (1 − A) are the relative fractions of the two components.

To explore the effects of TTX on inactivation curves of cells with a mix of TTX-sensitive and TTX-insensitive current, we performed a simple simulation. Combining Eqs. 2 and 3 for two components of current, with A being the fraction of TTX-insensitive current and (1 − A) the fraction of TTX-sensitive current, yields the following equation for total unblocked conductance at each drug concentration, with the first and second terms representing the TTX-insensitive and TTX-sensitive currents, respectively:

| (6) |

Vinact and s values for each current were taken from their average values in Table 2. A and the Kd values were estimated by fitting dose-response data from VGNs (see results).

Table 2.

Electrophysiological properties of NaV currents in vestibular ganglion neurons

| Inactivation |

Activation |

Time Course |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current/VGN Subpopulation | V1/2, mV | s, mV | V1/2, mV | s, mV | G density, nS/pF | tpeak, 0 mV, ms | tpeak, −15 mV, ms | τinact, 0 mV, ms |

| NaV (total) | ||||||||

| VGNs with INaI | −76.9 ± 1.5 (13) | 7.5 ± 0.4 (13) | −40.1 ± 2.0 (6) | 6.0 ± 0.6 (6) | 8.4 ± 0.9 (6) | 0.33 ± 0.03 (8) | 0.42 ± 0.03 (10) | 0.26 ± 0.02 (10) |

| VGNs without INaI or INaR | −79.5 ± 1.3 (3) | 6.6 ± 0.2 (3) | −38.6 (1) | 6.2 (1) | 7.24 (1) | 0.25 ± 0.003 (3) | 0.31 ± 0.01 (5) | 0.21 ± 0.01 (4) |

| cultured VGNs | −76.3 ± 0.2 (12) | 7.6 ± 0.1 (12) | −36.5 ± 1.6 (11) | 5.7 ± 0.4 (11) | 8.7 ± 1.0 (11) | 0.36 ± 0.01 (8) | 0.45 ± 0.01 (8) | 0.28 ± 0.01 (8) |

| NaS | ||||||||

| VGNs with INaI | −74.6 ± 1.5 (13) | 7.0 ± 0.3 (13) | −39.8 ± 2.5 (6) | 5.7 ± 0.8 (6) | 6.1 ± 0.4 (6) | 0.32 ± 0.03 (7) | 0.40 ± 0.04 (8) | 0.25 ± 0.02 (7) |

| VGNs with INaR | −65.8 ± 1.6 (8) | 10.5 ± 0.3 (8) | −32.3 ± 0.7 (6) | 5.9 ± 0.5 (6) | 3.1 ± 0.34 (5) | 0.45 ± 0.04 (5) | 0.57 ± 0.03 (5) | 0.312 ± 0.01 (5) |

| NaI | ||||||||

| VGNs with INaI + INaS | −102.1 ± 1.3 (23) | 9.9 ± 0.6 (23) | −47.5 ± 1.6 (9) | 8.2 ± 0.4 (9) | 1.0 ± 0.2 (9) | 0.47 ± 0.03 (9) | 0.53 ± 0.03 (11) | 0.27 ± 0.03 (8) |

| NaR | ||||||||

| VGNs with INaR + INaS | −31.4 ± 0.6 (23) | 5.2 ± 0.2 (23) | −16.5 ± 0.6 (8) | 4.5 ± 0.2 (8) | 1.5 ± 0.3 (7) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (6) | 3.1 ± 0.2 (6) | 2.4 ± 0.1 (11) |

Values are means ± SE (n). Sample sizes were smaller for activation parameters because higher recording quality is required. Room temperature, Cs+ internal, and Cs+ external solutions (Table 1). VGN, vestibular ganglion neurons; see text for additional definitions.

NaV1.8 Reporter Lines

We looked for evidence of NaV1.8 expression in two reporter mice: 1) an NaV1.8 reporter mouse generated by crossing the BAC transgenic “SNS-Cre” line (Agarwal et al. 2004) with a reporter line Rosa26LSL-tdTomato (Jackson Laboratory) in which a loxP-flanked STOP cassette prevented transcription of tdTomato, a variant of red fluorescent protein, under the CAG promoter (Madisen et al. 2009); and 2) the NaV1.8-Cre line, in which targeted knockin of Cre replaces the NaV1.8 sequence at its endogenous locus (Stirling et al. 2005). The mice used were hemizygous for SNS-Cre or heterozygous for NaV1.8-Cre and heterozygous for tdTomato. As a positive control for NaV1.8 expression and confirmation of genotyping, we dissected the trigeminal ganglia and DRG from the same animals; NaV1.8 is well documented in somatosensory neurons, including trigeminal ganglion cell bodies (Thun et al. 2009).

Reporter mouse tissues were also labeled with antibodies against calretinin, neurofilament 200 (NF200), and β-III tubulin, as described next.

Immunohistochemistry

Long-Evans rats (P3-P21) were deeply anesthetized with gaseous isoflurane or Nembutal (sodium pentobarbital, 80 mg/kg ip) and then either decapitated (younger animals, ages ≤ P6) or transcardially perfused (older animals, ages >P6) with 2 ml/g body wt of an aldehyde fixative [4% paraformaldehyde, 1% acrolein, 1% picric acid, and 5% sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4]. For young animals, the vestibular ganglia were quickly exposed and then tissue was transferred to 4% paraformaldehyde fixative for 20 min followed by rinses in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.01 M).

For SNS-Cre reporter mice, vestibular ganglia were dissected in L-15 and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2–3 h. For NaV1.8-Cre reporter mice, similar results were obtained whether the tissue was first dissected in L-15 and transferred to fix or fixed by transcardial perfusion of aldehyde fixative. Background fluorescence was reduced by incubating the tissues in a 1% aqueous solution of sodium borohydride for 10 min.

For NaV1.5 immunoreactivity and tissue from SNS-Cre mice, frozen sections (35 μm) were cut with a sliding microtome. NaV1.8-Cre ganglia were studied as whole mounts. Antibodies were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA) unless otherwise specified. Immunocytochemistry was performed on free-floating sections, permeabilized with Triton X-100 in a blocking solution of 0.5% fish gelatin and 1% BSA in PBS. Samples of vestibular tissues were incubated with Triton X-100 at concentrations that depended on age: P1: 0.3% overnight at 4°C; P3: 0.5% for 3 h at room temperature; P8: 2% for 1 h, room temperature; and P21 and adult: 4% for 1 h, room temperature. Samples were then incubated with a cocktail of two primary antibodies: goat anti-calretinin and rabbit anti-NaV1.5 (1:200 in the blocking solution) for 2 days at 4°C with 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5% Triton X-100 for P1, P3, and P8-adult sections, respectively. Specific labeling was revealed with a cocktail of two secondary antibodies: fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-goat and rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), all at 1:200 in the blocking solution. Sections were rinsed with PBS between and after incubations and mounted on slides in Mowiol (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). The sections were examined on a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510 META or LSM 710; Carl Zeiss, Oberköchen, Germany). Final image processing was done with Adobe Photoshop CS4 software (San Jose, CA).

For NaV1.5 immunostaining, two kinds of control reactions were done: 1) no primary antibody; and 2) primary antibody preincubated with the antigenic peptide (10 μg/1 μg antibody) for 1 h at room temperature. Images comparing labeling in control and test conditions were acquired and digitally processed identically.

In addition, Western blots, performed as described in Wooltorton et al. (2007), yielded a band at the appropriate size (227 kDa) for inner ear and control tissue (heart) prepared from adult rats.

RESULTS

Expression of NaV Channel Subunits in the Vestibular Ganglion

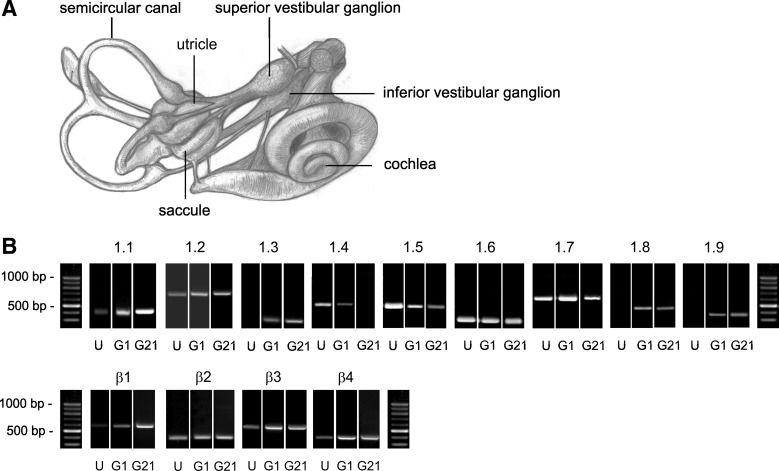

RT-PCR revealed robust expression of NaV pore-forming (α) subunits and accessory (β) subunits in the superior compartment of the vestibular ganglion, which contains neuronal cell bodies and their satellite cells (Fig. 1). Data were obtained from the ganglion at P1 and at P21. At P1, all known NaV α-subunits were detected; at P21 all were detected except NaV1.4, the skeletal muscle subunit. Most α-subunits (NaV1.1–1.4, 1.6, and 1.7) carry TTX-sensitive currents. NaV1.5 carries TTX-insensitive current and is prevalent in cardiac muscle but also reported in neurons, including somatosensory ganglion neurons (Renganathan et al. 2002), and in hair cells of the rat utricular macula (Wooltorton et al. 2007). NaV1.8 and 1.9 carry TTX-resistant current in somatosensory ganglion neurons. All four β-subunits were expressed.

Fig. 1.

Vestibular ganglia expressed mRNA for multiple Na channel α- and β-subunits at both postnatal day (P) 1 and P21. A: sketch of the mammalian inner ear [adapted from Fig. 7 by M. Brödel in Hardy (1934) with permission from John Wiley and Sons]. The superior division of the vestibular ganglion was taken from P1 and P21 rats for RT-PCR experiments. B: representative agarose gels of PCR products (40 amplification cycles) are shown for individual ganglia at P1 (“G1”) and P21 (“G21”) for each α-subunit (1 to 9) and each β-subunit (1–4). Results from P1 utricular epithelia (“U”) processed in the same experimental series serve as negative controls for positive ganglion expression in some cases (NaV1.3, 1.8, and 1.9). Each ganglion was processed in an independent experiment. PCR products were detected in most ganglia. Products for α1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7, and β1, 3, and 4 were detected in every ganglion (n = 5). Products for α1.8 and 1.9 were detected in every P1 ganglion (n = 4 and 5, respectively). At P21, α1.8 was detected in 4 of 5 ganglia and α1.9 was detected in 3 of 4 ganglia. α1.6 was detected in 4 of 5 ganglia at P1 and β2 was detected in 2 of 3 ganglia at P21. Product for NaV1.4 was detected in 3 of 5 ganglia at P1 but in 0 of 2 ganglia at P21. Controls: water (no template) negative controls are shown in Wooltorton et al. (2007) (their Fig. 11, A and B). (−)RT: controls, in which reverse transcriptase was left out, were also done for each tissue (not shown). Bands were verified by sequencing. [Some RT-PCR bands were previously published in Fig. 9, A and B, of Wooltorton et al. (2007) on NaV channels in utricular hair cells: all of the utricular bands (“U”) and the bands in ganglia for NaV1.7, 1.8, and 1.9 subunits. The ganglion data served in Wooltorton et al. (2007) as positive controls for negative results in the sensory epithelia of utricles and semicircular canals.]

The positive results for NaV1.5, NaV1.8, and NaV1.9 primers were remarkable given previous reports that all NaV current in VGNs was TTX sensitive. These RT-PCR results on vestibular ganglia were obtained in parallel with RT-PCR results for vestibular (utricular and semicircular canal) epithelia and controls that are reported in Wooltorton et al. (2007). Water (no template) controls and −RT (no reverse transcriptase) controls were negative. In vestibular epithelia, all β-subunits and most α-subunits were detected at P1 and/or P21, but NaV1.8 and NaV1.9 subunits were never detected. Correspondingly, no TTX-resistant currents were recorded in utricular hair cells. These clear negative results serve as an additional control for the strong NaV1.8 and NaV1.9 expression of the vestibular ganglia (Fig. 1B). Positive support for the NaV1.5 result in vestibular ganglia is provided by strong NaV1.5-like immunoreactivity in the distal calyceal terminals (Wooltorton et al. 2007; Lysakowski et al. 2011) of VGNs. In this report, we provide further support for expression of NaV1.5 and NaV1.8 subunits in vestibular ganglion cell bodies in the form of whole cell currents, immunostaining of the cell bodies (NaV1.5), and results with reporter mice (NaV1.8).

To look for functional expression of NaV channels in vestibular afferents, we dissociated VGNs from P1–P8 rats and recorded whole cell currents (n = 239 VGNs) within 7 h of dissociation. Dissociated neuronal somata are more accessible than neuronal terminals in situ and allow better space clamp. Recordings were restricted to the early postnatal period because increasing myelination of vestibular ganglion cell bodies (Dechesne et al. 1987) interferes with patching the neuronal membrane at later ages. In some previous reports, VGNs have been studied after overnight culturing, which reduces myelin and satellite cell coverage of the cell bodies. As described later, we found that culturing overnight may affect expression of NaV channels and have excluded data from overnight-cultured neurons except where indicated.

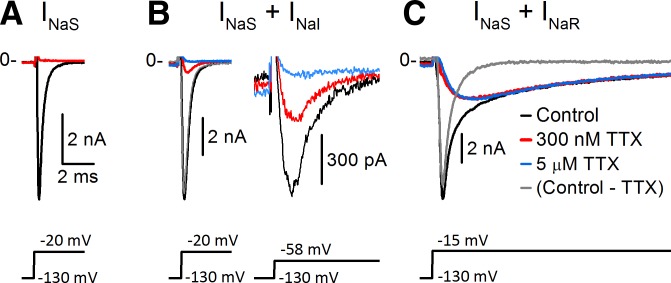

In all VGNs, fast inactivating inward current was evoked by depolarizing voltage steps following a hyperpolarizing prepulse (Fig. 2). Most recordings were made in solutions designed to minimize K+ and Ca2+ currents (Cs+ internal solution and Cs+ external solution with TEA and only trace Ca2+; Table 1). Experiments described later confirm that these are Na+ currents. We refer to the total voltage-dependent Na+ current as INaV. Application of the classic NaV channel blocker TTX revealed that INaV comprised currents with three different TTX sensitivities in different combinations. TTX-sensitive current (INaS) was present in all VGNs. In 32 of 109 (29%) VGNs, the total inactivating current was fully blocked by 300 nM TTX (Fig. 2A). Currents that were not TTX sensitive fell into two distinct categories. In many VGNs (69/111, 62%), a fast inward TTX-insensitive current (INaI) remained in 300 nM TTX (Fig. 2B). INaI was a small proportion of total INaV at −20 mV (Fig. 2B, left) but a much larger proportion at −58 mV (Fig. 2B, right), indicating that INaI had a negatively shifted activation range compared with INaS. Other VGNs (47/178, 26%) had INaR, a TTX-resistant inward current that was not blocked by micromolar levels of TTX and had slower kinetics and a less negative voltage range than either INaS or INaI (Fig. 2C). (Sample sizes differ because different conditions were used to detect different NaV components.) In no case did we detect both INaI and INaR in a single cell, although small levels of expression cannot be ruled out. Evidence on the identities of the channels carrying INaI and INaR is provided in sequence in the following sections. In addition, we show that the properties of INaS differed depending on whether INaR was also present.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological dissection with tetrodotoxin (TTX) revealed 3 types of Na+ current composition in vestibular ganglion neurons (VGNs), as shown by these representative examples. Legend in C applies to A–C. Recording solutions in this and all subsequent figures were Cs+ internal and Cs+ external (Table 1) unless otherwise specified; channel blockers were added to the external solution. VH = −70 mV in all figures. Voltage was first stepped to −130 mV to de-inactivate INaV, then stepped to a depolarized value. All currents are shown on the same time scale, but amplitude has been scaled for display. Transient capacitive artifact at the voltage step was truncated in this and subsequent figures. A: INaV was completely blocked by 300 nM TTX in some VGNs, indicating that it was entirely TTX sensitive (INaS). Data are from P3 VGN. B: some VGNs expressed a mixture of INaS and a more negatively activating TTX-insensitive current (INaI). INaI was small relative to total INaV for a step to −20 mV (left) but more prominent for a step to −58 mV (right, expanded current scale) because it activated at more negative voltages. Data are from P2 VGN. C: other VGNs had a mixture of INaS and a slower, more positively activating TTX-resistant current (INaR). Note that the residual inward current in 300 nM TTX (red) was little affected by increasing TTX to 5 μM (overlapping blue trace). Data are from P7 VGN. Gray, difference current between the control current and the current in 300 nM TTX.

INaI Is Carried by Nav1.5 Channels

INaI resembled current carried by NaV1.5 channels in its TTX sensitivity, voltage dependence and kinetics, and sensitivity to block by divalent cations.

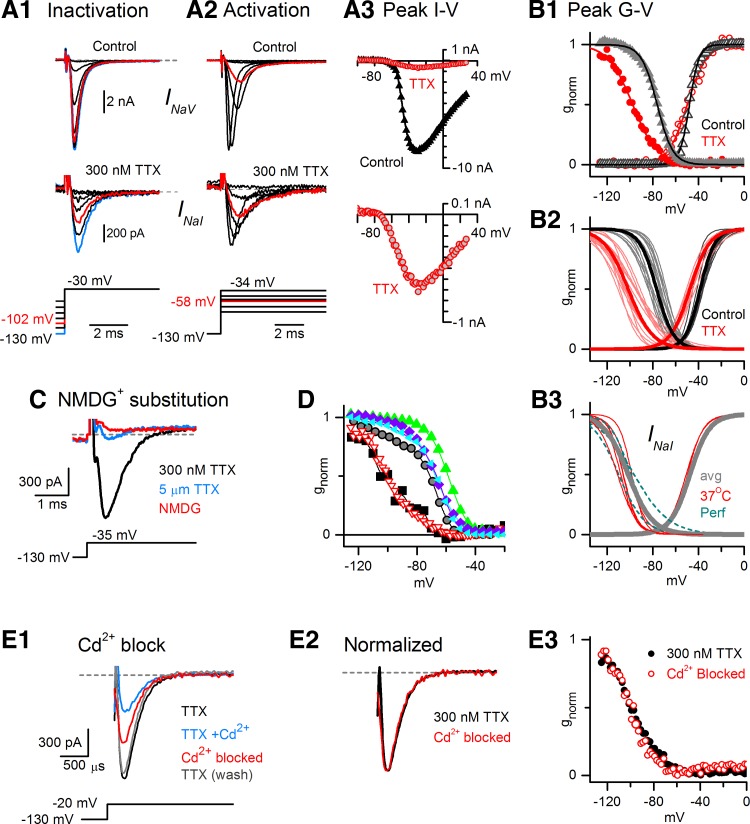

Reported Kd values for TTX block are 1–10 nM for TTX-sensitive currents and ∼100-fold higher for Nav1.5 current (Cribbs et al. 1990). To look for NaV1.5 current, we applied 300 nM TTX, which would block most TTX-sensitive current while significantly sparing any NaV1.5 current. The small current remaining in 300 nM TTX (INaI) activated and inactivated at substantially more negative voltages than total INaV in 0 TTX did (Fig. 2B; Fig. 3A and B), indicating that INaI was a distinct current component. INaI was blocked by a higher concentration of TTX (5 μM) and eliminated by replacing Na+ with the impermeant ion NMDG+ (Fig. 3C), confirming that it was a Na+ current. Even in VGNs with INaI, 300 nM TTX blocked total INaV by ∼90% (at −25 to −35 mV, Fig. 3A3), indicating that most of the NaV current was TTX sensitive. In control conditions, therefore, INaI was masked by the much larger INaS, such that the voltage dependence of total INaV was similar to that of TTX-sensitive channels (Fig. 3, B1 and B2, and Table 2). The masking of INaI by INaS in inactivation curves in 0 TTX is explored in a later section.

Fig. 3.

Some VGNs expressed TTX-insensitive Na+ current (INaI) with the properties of NaV1.5 channels, in addition to INaS. A and B: current remaining in 300 nM TTX (INaI) had more negative voltage dependence than total NaV current. Data are from P2 VGN. A1: inactivation: as prepulse voltages (bottom) became less negative, the peak current evoked by the step to −30 mV decreased in both control and 300 nM TTX solutions but with different voltage dependence: a prepulse to −102 mV (red traces) decreased total INaV only slightly (top) relative to the peak value (blue traces, prepulse to −130 mV) but inactivated approximately half of INaI (bottom). A2: activation: at −58 mV (red traces), INaV was one-quarter maximal but INaI was nearly half-maximal. A3: current-voltage relation: peak inward current in control and 300 nM TTX solutions (top) for the VGN in A1 and A2 shows a small TTX-insensitive component (red) that activated at relatively negative potentials (y-scale expanded, bottom). B: conductance-voltage (G-V) relations for activation and inactivation. B1: normalized plots of activation (peak current vs. test step, open symbols) and inactivation (peak current vs. prepulse, filled symbols) and Boltzmann function fits (curves); for the VGN in A. Gray triangles, total INaV; red circles, INaI. B2: population data. Thin curves, all fits for room temperature, ruptured-patch data. Thin gray curves, total INaV for VGNs with both INaS and INaI or just INaS. Thin red curves, INaI, obtained in 300 nM TTX. Thick black and red curves, curves generated with average fit parameters, Table 2. B3: INaI voltage range was still negative when recorded at body temperature (red curves) or at room temperature with the perforated patch method (dark cyan curves; inactivation curves only). Thick gray curves, population averages for INaI from B2 (ruptured patch, room temperature). C: INaI in 300 nM TTX (black) was strongly blocked by 5 μM TTX (blue) and abolished by replacing external Na+ with NMDG+ (red, no TTX present), demonstrating that it is carried by Na+ ions flowing through NaV channels (K+ internal, K+ external, P7). D: voltage range of inactivation recorded in 300 nM TTX did not shift negatively with time, as illustrated by inactivation curves taken at different times since patch rupture. Negative inactivation ranges were recorded immediately post rupture: inverted red open triangles, 300 nM TTX, 10 s after rupture. In 0 TTX, inactivation ranges of total INaV did not shift negatively with time: cyan triangles and purple diamonds, 2 VGNs, 7.5 min since rupture; green triangles, a 3rd VGN, 13 min since rupture. Removal of TTX shifted inactivation curves positively despite increasing time since rupture: black squares, in 300 nM TTX; gray circles, the same VGN later, after stopping TTX application. E: INaI (isolated in 300 nM TTX) was partially and reversibly blocked by 200 μM external Cd2+. The Cd2+-blocked (difference) current (E1, P4) had similar time course (E2, normalized E1 data) and voltage dependence (E3, different VGN, P2) to the current in 300 nM TTX, consistent with them being one and the same.

The activation and inactivation midpoints of INaI were, respectively, ∼10 and ∼25 mV negative to the midpoints for the total current (Table 2; P = 0.009 relative to INaS in cells without INaR). Reported Vinact values for NaV1.5 channels range from −106 to −82 mV (DiFrancesco et al. 1985; Frelin et al. 1986; Sheets and Hanck 1992, 1999; Yamamoto et al. 1993; Wang et al. 1996; Cummins et al. 1998; O'Leary 1998; Zhang et al. 1999; Kuo et al. 2002; Wooltorton et al. 2007), compared with −35 to −78 mV for TTX-sensitive channels (Noda et al. 1986; Sangameswaran et al. 1997; Dietrich et al. 1998; Smith and Goldin 1998; Chen et al. 2000; Moran et al. 2003) and approximately −30 mV for NaV1.8 channels (discussed later). Thus the Vinact value of INaI is consistent with NaV1.5 and no other NaV α-subunits.

Since INaI activated at significantly more negative voltages than other NaV currents, it contributed significantly to Na+ current evoked by steps from hyperpolarized voltages to near resting potential (Fig. 2B, right). The averaged inactivation and activation curves cross over at −71.5 mV for INaI and −56.0 mV for INaV, with crossover conductance levels at 6% of peak and correspondingly small window currents (Fig. 3B2). Resting membrane potentials range from −75 to −45 mV in isolated VGNs of the first postnatal week (present study and Kalluri et al. 2010) and could be less negative in vivo under the influence of excitatory synaptic input from hair cells. For resting potentials positive to −70 mV, our results indicate that INaI channels would be mostly inactivated. We investigated two factors that might negatively shift the voltage range of NaV channels in our experiments: temperature and second messenger availability. Increasing temperature from room to 37°C can shift the inactivation range of NaV channels positively (Ruppersberg et al. 1987; Oliver et al. 1997). For INaI in our cells, however, Vinact was similar at 37°C (−103.3 ± 1.5 mV, n = 6) and room temperature (−100.6 ± 1.6 mV, n = 15; P = 0.34; Fig. 3B3).

Alternatively, loss of intracellular signaling molecules during ruptured-patch recording might shift Vinact negatively (e.g., Penniman et al. 2010). To test for such washout effects, we recorded from three VGNs with the perforated-patch method. The inactivation range of INaI was still very negative (Vinact = −101.8 ± 4.1 mV; no significant difference from ruptured-patch recordings, P = 0.78; Fig. 3B3). Ruptured-patch data in Fig. 3D further indicate that the negative inactivation range was not a washout or rundown artifact: 1) the negative inactivation range could be seen within seconds of patch rupture (red inverted triangles); 2) in 0 TTX, the inactivation range of total current, INaV, did not shift negatively in ∼10 min following patch rupture (purple, cyan, and green curves show data from 3 cells); 3) removing TTX from the external solution moved the inactivation range of total NaV current positively with time (compare black squares, taken early in TTX, and gray circles, taken later from the same VGN after removing TTX).

Another property of NaV1.5 currents that distinguishes them from TTX-sensitive currents is a relatively high sensitivity to block by Cd2+ and Zn2+ (Backx et al. 1992; Chen et al. 1992; Heinemann et al. 1992; Satin et al. 1992). Reported half-blocking concentrations (IC50) of Cd2+ for NaV1.5 current are 50–250 μM (DiFrancesco et al. 1985; Scornik et al. 2006; Wooltorton et al. 2008), in contrast to 5 mM for TTX-sensitive currents (Frelin et al. 1986; Roy and Narahashi 1992). Like NaV1.5 current, INaI was ∼half-blocked by 200 μM Cd2+ (Fig. 3E), a dose that barely affects TTX-sensitive current. We first isolated INaI by recording in Cs+-based external solution with 300 nM TTX and then added 200 μM CdCl2 to the external solution (Fig. 3E1). In 13 cells, 200 μM Cd2+ reversibly blocked INaI at −20 mV by 53 ± 4%. Assuming that the block is of a single current, the measured block yields a Kd of 179 μM (Eq. 4), consistent with the reported range for NaV1.5 channels. (Note that the Kd for Cd2+ may be lower in 0 TTX because Cd2+ competes with TTX for a common binding site; Doyle et al. 1993; Renganathan et al. 2002.) INaS at −20 mV was negligibly blocked by 200 μM Cd2+ in three of three cells (block of 0.6 ± 4.7%). The current blocked by 200 μM Cd2+ resembled the total current in 300 nM TTX (INaI) in its kinetics (Fig. 3E2, normalized currents) and voltage dependence of inactivation (Fig. 3E3), supporting the interpretation that INaI is dominated by a Cd2+-sensitive inward current with fast kinetics and relatively negative voltage range.

Given that INaI was partly blocked by 200 μM Cd2+, a known blocker of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, how can we be certain that it was not carried by CaV channels? This conclusion is based on multiple arguments: 1) INaI was almost entirely blocked at 5–10 μM TTX (n = 7; Fig. 3C). In two cells, we were able to test for reversibility and in both cases the additional block by 5–10 μM TTX could be reversed and re-applied multiple times. The difference current obtained by subtracting current in 5 or 10 μM TTX from current in 300 nM TTX had similar biophysical properties to INaI, consistent with INaI being primarily a single TTX-blockable current. 2) INaI was eliminated by replacing external Na+ with the impermeant ion NMDG+ (Fig. 3C). This effect was almost fully reversible (>95%, 3 VGNs). 3) The biophysical properties of INaI were not consistent with those of inactivating T-type Ca2+ currents. INaI inactivated with a time constant of ∼300 μs at 0 mV and was half-inactivated at approximately −100 mV (Table 2), in contrast to T-type Ca2+ currents, which have inactivation time constants ranging from ten to hundreds of milliseconds (depending on voltage and subunit) and Vinact values from −47 to −86 mV (Coulter et al. 1989; Monteil et al. 2000; Chemin et al. 2001; Gomora et al. 2002; Díaz et al. 2005; Nelson et al. 2005; Vitko et al. 2005; Emerick et al. 2006; Zhong et al. 2006). The fast inactivation of L-type Ca2+ current is relatively slow, with time constants of ∼15 ms or more (Beuckelmann et al. 1991; Mewes and Ravens 1994; Magyar et al. 2000) and is Ca2+ dependent, with reduced extent and speed of inactivation when Ba2+ or Na+ (in μM Ca2+) is the charge carrier (Brehm and Eckert 1978; Lee et al. 1985; Ferreira et al. 2003; Brunet et al. 2009). In contrast, we observed rapid and near complete inactivation of INaI when Na+ was the charge carrier and current was eliminated by Na+ replacement (Fig. 3C). 4) Erev for INaI was consistent with a Na+ current. For our usual recording solutions (Cs+ internal and Cs+ external, Table 1), we estimated Erev from I-V curves (see materials and methods) as +49 ± 2 mV (n = 10) for total NaV current and +50 ± 5 mV (n = 6) for INaI. ENa calculated from the nominal Na+ concentrations (Table 2) equaled +62 mV but Erev is expected to be lower because of nonnegligible Cs+ permeability, PCs. Ratios of PCs to PNa for mammalian cardiac NaV currents, which INaI closely resembles, range from 0.007 to 0.06, with a mean across studies of 0.02 (reviewed in Kurata et al. 1999). In our solutions, the predicted Erev for a permeability ratio of 0.02 is +53 mV, close to the value (+50 mV) extrapolated from the INaI I-V relations. 5) Our external solutions for recording NaV currents contained only trace (no added) Ca2+. CaV channels do become permeable to Na+ at concentrations of Ca2+ <10 μM (Almers and McCleskey 1984; Hess and Tsien 1984), but to achieve such low concentrations usually requires chelators, which we did not include. Moreover, the voltage dependence of CaV channels is similar whether the current is carried by Na+ or Ca2+ (Fukushima and Hagiwara 1985), and, as already noted, the voltage dependence of INaI is very different from that of T-type channels. Our external solution included 3.5 mM Mg2+ to help counter the effects of low Ca2+ on apparent voltage dependence (Frankenhaeuser and Hodgkin 1957) and to block CaV channels (Fukushima and Hagiwara 1985; Kurejová et al. 2007). It is improbable that INaI, which was as large as 2 nA (below), was carried by trace Ca2+ or by Na+ through partly blocked CaV channels.

Sizes and Proportions of INaV, INaS, and INaI Current

Total peak current (INaV) for cells without INaR was −13.1 ± 1.8 nA (n = 6; range −5.7 to −17.0 nA) in K+ internal solution and K+ external solution (100 mM Na+) and −11.7 ± 0.9 nA (n = 21) in Cs+ internal solution and Cs+ external solution (80 mM Na+). [Note that external Na+ was reduced from physiological levels (∼145 mM) to reduce current size and associated voltage-clamp errors.] The mean peak current in 300 nM TTX (INaI) was −1.2 ± 0.2 nA (n = 6) (range −0.6 to −2.2 nA) for K+ internal and K+ external solutions and −834 ± 115 pA (n = 24) for Cs+ internal and Cs+ external solutions. Peak INaS, estimated by subtracting the current in 300 nM TTX from the control condition, was −12.3 ± 1.6 nA (n = 14; all solutions). Because INaI was partly blocked in 300 nM TTX, these estimates underestimate INaI and overestimate INaS.

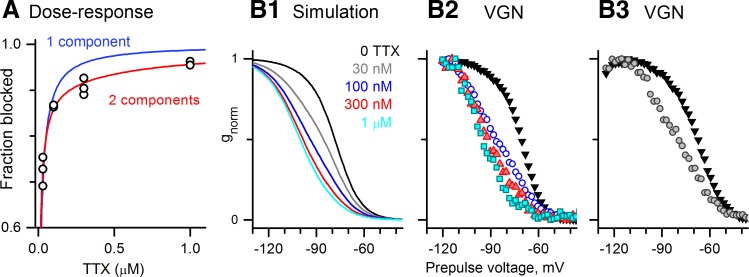

We estimated proportions of INaS and INaI in VGNs with both currents from the dose-response curve for the total NaV current at −15 mV. A dose-response curve of 11 normalized data points pooled from five cells (Fig. 4A) is better fit by a two-component model (Eq. 5) than a one-component model (Eq. 3); the deviation of the data from a single-component fit exceeds the variability between the data points. According to the two-component fit, INaI was 8.4% of the total current and had an IC50 of 774 nM; INaS constituted the remainder with an IC50 of 8 nM. These values are consistent with the range reported for NaV1.5 currents (150 nM to 2 μM; reviewed in Wooltorton et al. 2008) and the range of 1–10 nM typical of TTX-sensitive currents.

Fig. 4.

TTX-insensitive current was ∼10% of the total Na+ current in VGNs with INaI and was not readily evident in the absence of TTX. A: TTX dose-response data (11 data points from 5 VGNs) deviated from a single-component fit to the Hill equation (Eq. 3, blue, Kd = 13 nM) but was well fit by a 2-component fit (Eq. 5, red), with Kd1 = 8 nM, Kd2 = 774 nM, and A (fraction of TTX-sensitive component) = 0.92. B: inactivation curves recorded for different TTX doses are consistent with the predictions of the 2-component fit. B1: voltage dependence of inactivation at 5 TTX concentrations, simulated with Eq. 6: 10% INaI (Vinact = −96 mV, s = 8 mV, Kd2 = 700 nM) and 90% INaS (Vinact = −74 mV, s = 5.6 mV, Kd1 = 5 nM). Parameter values for TTX dependence were close to the results of the 2-component fit (Kd1, Kd2, A). Inactivation parameters were the means obtained for INaI and INaS (Table 2). B2 and B3 inactivation curves from 2 representative VGNs (P2 and P1, respectively) at different TTX doses resemble the simulations in B1 at corresponding TTX doses. Key colors in B1 apply to B1-B3.

If INaI is present within the total NaV current, why is it not visible as a separate component in the inactivation curves? To explore this question, we used Eq. 6 to simulate, for various TTX concentrations, the inactivation curve for total NaV current in a cell with 10% INaI plus 90% INaS and Kds of 800 and 5 nM, respectively, similar to the IC50s of the two-component fit in Fig. 4A. The inactivation midpoints and slopes of the two inactivation components in Eq. 6 were set to the average values for INaI and for INaS in VGNs with INaI (Table 2). The effect of INaI on the shape of the simulated inactivation curve at different TTX doses (Fig. 4B1) reproduces data (Fig. 4, B2 and B3) well and shows that in such a mixture, INaI cannot be distinguished as a separate component, especially at 0 TTX where INaS dominates. At moderate TTX doses (100–300 nM), Vinact shifted negatively and the slope decreased, consistent with a more balanced contribution of two currents. The mean s value for the inactivation curve was 7.4 ± 0.2 mV (n = 27) at 0 TTX; in contrast, s values were between 12.4 and 13.4 in four of five cells in 100 nM TTX. At high TTX doses (1 μM), INaI dominated.

Although INaI was just 10% of total NaV current at −15 mV, its maximum size of ∼200 to ∼2,000 pA in 100 mM external Na+ (and larger in physiological Na+ concentrations) is well above current thresholds for spiking, particularly in VGNs of the first postnatal week (10–100 pA, Kalluri et al. 2010). The mean INaI conductance density was 1.0 ± 0.2 nS/pF (n = 9), 8% of the mean total NaV conductance density per cell (13.0 ± 2.6 nS/pF, n = 9).

Our results suggest several reasons that NaV1.5 current has not been reported previously in VGNs. First, even in cells with INaI, the total current had similar biophysical properties to INaS, as predicted for cells with a ∼10% contribution of INaI (Fig. 4B). Second, the very negative inactivation range of INaI required a deeply hyperpolarized prepulse (to −130 mV in Fig. 3A1) to relieve inactivation and fully reveal the full conductance. Using less negative prepulses (Chabbert et al. 1997; Risner and Holt 2006) would reduce the pool of NaV1.5 channels available for activation. Third, the practice of culturing ganglion neurons overnight to reduce satellite cell coverage may suppress INaI expression either by the conditions or the passage of time ex vivo: in 14 VGNs that we recorded from after overnight culture, INaI was small or undetectable. We also did not observe INaR in cultured cells but did not specifically test for it. Fourth, it is not uncommon in NaV channel studies to add Cd2+ to block CaV channels, and this would block NaV1.5 channels.

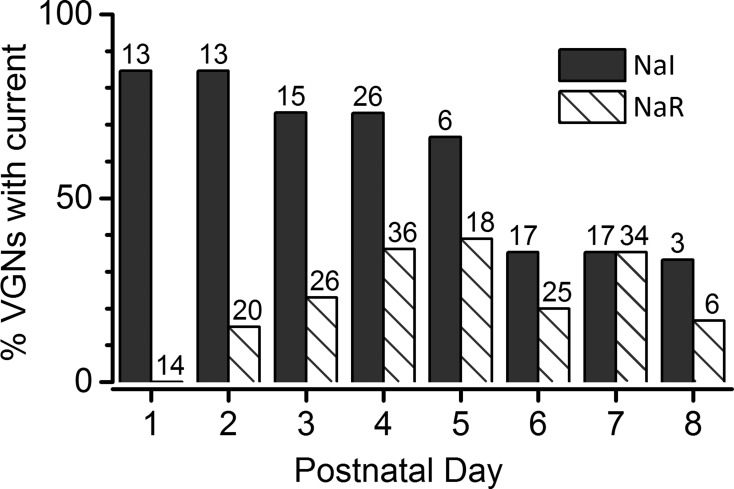

Finally, VGN maturation may play a factor in whether INaI is detected in VGNs. In our sample, the incidence of INaI in VGN cell bodies decreased toward the end of the first postnatal week (Fig. 5, dark bars). To estimate the incidence of INaI, we counted only cells that had total peak INaV larger than 4 nA in 0 TTX; for smaller INaV, the voltage dependence of the much smaller TTX-insensitive component was difficult to analyze. INaI was identified by its TTX insensitivity or Cd2+ sensitivity and its kinetics and voltage range. For VGNs dissociated on P1–P5, 60–85% of the recorded VGNs had detectable INaI. By P6–P8, the incidence dropped to 30–40%.

Fig. 5.

The incidence of TTX-insensitive and TTX-resistant currents in our samples of isolated rat VGNs changed over the 1st postnatal week. Total number of VGNs at each age is shown above each column.

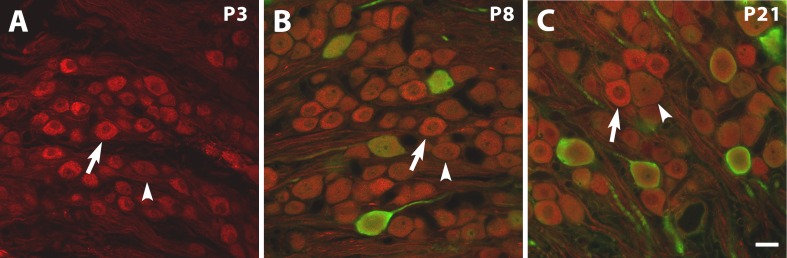

NaV1.5-Like Immunoreactivity in VGN Somata

The calyceal terminals of VGNs on type I hair cells in vestibular epithelia are strongly stained by NaV1.5 antibody during development (Wooltorton et al. 2007) and in adult (Lysakowski et al. 2011). With the same antibody, we also observed immunoreactivity in cell bodies within the ganglion, examined from ages P3–P21 (Fig. 6). Use of calretinin antibody at P8 and P21 showed that some NaV1.5-immunoreactive VGNs were also immunoreactive for calretinin, a marker for the large, irregularly-firing “calyx-only” afferents that form calyceal terminals on type I hair cells in the central zones of vestibular epithelia (Desmadryl and Dechesne 1992; Kevetter and Leonard 2002; Leonard and Kevetter 2002; Desai et al. 2005a,b).

Fig. 6.

NaV1.5-like immunoreactivity (red) in the rat superior vestibular ganglion at different ages. Calretinin antibody (green) was added at P8 (B) and P21 (C) to label the relatively large somata of calyx-only afferents, which selectively innervate type I hair cells in central zones of vestibular epithelia. At P3 (A), no calretinin antibody was applied because vestibular afferents are not calretinin-immunopositive. Arrows, examples of bright NaV1.5 staining at each age. Arrowheads, dimmer staining. The 20-μm scale bar in C applies to A–C.

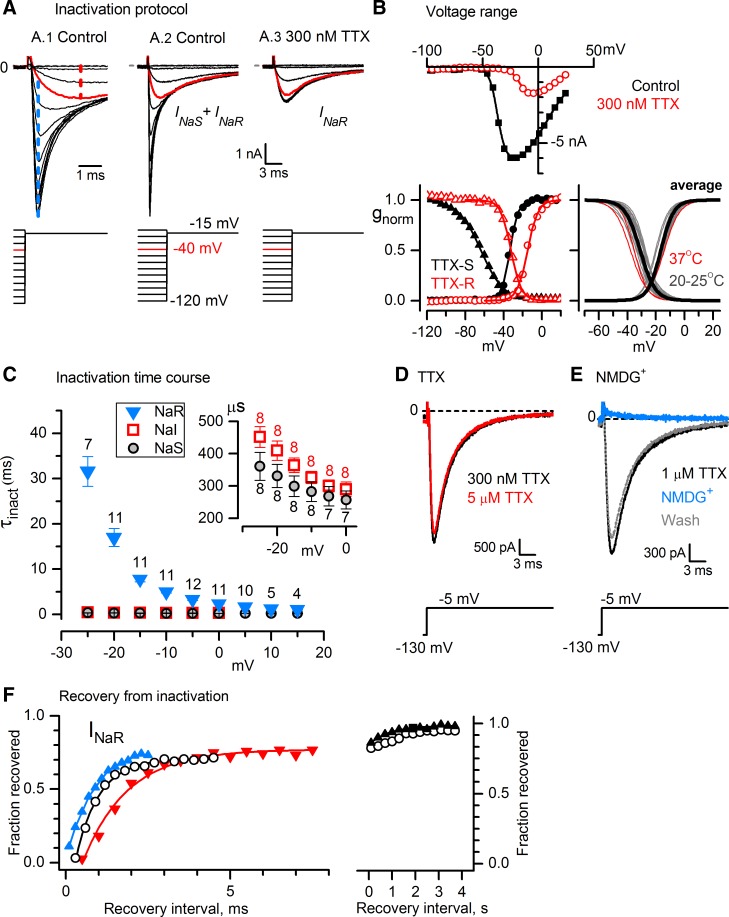

INaR Is Carried by Nav1.8 Channels

In approximately one-quarter (47/178) of VGNs, depolarizing voltage steps in 300 nM TTX evoked a relatively slow inactivating inward current, INaR, which resembled currents carried by NaV1.8 (SNS, PN3) channels, first identified in DRG (Akopian et al. 1996; Sangameswaran et al. 1996). Distinctive properties of NaV1.8 current include TTX resistance, relatively positive voltage dependence, slow time course, and rapid recovery from inactivation. INaR was readily detected in the presence of other NaV currents by its distinctive voltage range and time course (Figs. 2 and 7, A–C). In all cases of INaR recorded in 0 TTX (n = 20), INaS was also present. In all cases of INaR recorded in 300 nM TTX to block most INaS, either no fast component (9 cells) or only a very small fast component (12 cells) could be discerned. Where it was possible to analyze that fast component (5 cells), it resembled INaS rather than INaI. Thus we recorded no examples of INaR and INaI in the same cell.

Fig. 7.

Some VGNs expressed a TTX-resistant NaV current (INaR) with properties of NaV1.8 channels. A: in responses to an inactivation protocol with VH −70 mV, 80-ms prepulse, and test step to −15 mV, INaR was distinguished from INaS by its less negative voltage dependence and slower time course for P6 VGN. Vertical scale bar applies to A1-A3; A1 has a shorter time scale than A2 and A3. A1 and A2: control data (K+ internal, K+ external). A1's expanded time scale shows separation of INaS (blue dashed line) and INaR (red dashed line) with voltage and time, allowing estimation of their amplitudes in 0 TTX (see results). After a prepulse to −40 mV (red traces), INaS was almost completely inactivated but INaR was minimally inactivated; thus peak current after a −40-mV prepulse provided an estimate of INaR. Conversely, the difference current (blue dashed line) between −120- and −40-mV prepulses was almost entirely INaS. This method was validated by blocking INaS with 300 nM TTX (A.3), which did not affect current after the −40-mV prepulse (red trace, compare to control), confirming that it was INaR. B: voltage ranges of activation and inactivation. Solutions: Cs+ internal, Cs+ external. Top: peak I-V relations in control and 300 nM TTX, for the cell in A. Bottom left: activation data (circles) and inactivation data (triangles) for INaS obtained by subtracting traces in 300 nM TTX from control traces (black) and for INaR obtained in 300 nM TTX (red), for the cell in A. Data were fitted with Eqs. 1 and 2. INaR inactivation curve: Vinact = −32.1 mV, s = 5.4 mV; activation curve: Vact = −14.8 mV, s = 5.4 mV, gmax = 51.1 nS. INaS inactivation curve: Vinact = −63.6 mV, s = 11.9 mV; activation curve: Vact = 33.4 mV, s = 4.3 mV, gmax = 106.0 nS. For B, g was normalized to gmax. Bottom right: superimposed activation and inactivation curves from individual fits (thin gray lines, room temperature) and average fits (thick black lines) are shown. Average parameter values are in Table 2. Thin red lines, data at 37°C, not in average. C: time constants of fast inactivation of INaR decreased 10-fold to ∼2 ms as voltage was made less negative over the range from approximate Vinact to +15 mV; prepulse was −125 mV, 50 ms. Numbers of values averaged (one per VGN) are indicated above each data point. Inset: much smaller averaged values for INaS and INaR on an expanded ordinate. D: INaR was blocked only slightly more (7%) by 5 μM TTX than by 300 nM TTX. Data are from P7 VGN. E: INaR was completely and reversibly eliminated by replacing external Na+ with NMDG+. Data are from P5 VGN. F: INaR recovery at −90 mV from inactivation during 25-ms steps at 0 mV, in 4 VGNs. INaR recovered ∼75% within ms (left) but took seconds to recover fully (right). Solutions were Cs+ internal and Cs+ external except for blue triangles: K+ internal, K+ external (P7). Open circles, P7 (same VGN at left and right). Red inverted triangles, P2. Black triangles, P5.

For analyses of biophysical properties, we used a subset of 23 VGNs that satisfied two criteria: almost all INaS was blocked, and unblocked outward current that overlapped in time and voltage dependence with INaR was at least 15-fold smaller than the peak inward INaR. The voltage dependence (Fig. 7B) and time course (Fig. 7, A and C) of INaR (Table 2) were similar to reported values for NaV1.8 current in somatosensory afferent neurons.

Inactivation and activation curves of INaR were well fit by single Boltzmann functions (Fig. 7B, bottom left), with midpoints of −31 and −16 mV (Table 2), comparable to values between −25 to −35 mV and −15 to −20 mV, respectively, for NaV1.8 currents in DRG neurons (Akopian et al. 1996; Cummins and Waxman 1997; Sangameswaran et al. 1997; Leffler et al. 2005). NaV1.9 channels (reviewed in Dib-Hajj et al. 2015) have substantially more negative midpoints of activation and inactivation (−50 to −60 mV) and a larger window current. Relative to INaI and INaS, the time to peak, tpeak, for INaR was three- to fourfold slower at 0 mV and eightfold slower at −15 mV (Table 2) and consistent with tpeak values for NaV1.8 channels of ∼2 ms at ∼0 mV (Elliott and Elliott 1993; Scholz et al. 1998). Inactivation of INaR was well fit by a single exponential with a time constant of ∼2.5 ms at 0 mV and ∼8 ms at −15 mV, slower than INaS and INaI (Table 2 and Fig. 7C) and close to inactivation time constants of NaV1.8 currents (3.5 ms at 0 mV, 9 ms at −15 mV; Renganathan et al. 2002).

INaR was highly resistant to TTX. In Fig. 7D, increasing the TTX concentration from 300 nM to 5 μM, a dose that blocked most of INaI, produced only 7% additional block of INaR. Solving Eq. 4 for the effect yields a Kd of 61 μM, within the expected range for either NaV1.8 channels or NaV1.9 channels (IC50 values 40 to >100 μM; Akopian et al. 1996; Sangameswaran et al. 1996; Rabert et al. 1998; Cummins et al. 1999).

INaR was carried by Na+. Substitution of external Na+ with NMDG+ reversibly eliminated the current (Fig. 7E; eliminated in 13/13 cells; reversed in 7 of 7 cells that were tested for reversibility). Erev for INaR in Cs+ external solution was +50 ± 2 mV (n = 9), similar to Erev estimates for total INaV and INaI (49−50 mV, above).

NaV1.8 current recovers from fast inactivation an order of magnitude faster than TTX-sensitive current recovers at the same voltage (Elliott and Elliott 1993), consistent with the general observation that time constants for macroscopic transitions of channel states become faster away from the midpoint of the inactivation range. The fast recovery time constant of INaR from inactivation at −90 mV (1.0 ± 0.2 ms, n = 3, Fig. 7F, left) is consistent with recovery time constants for NaV1.8 currents in small DRG neurons (∼1 ms at −100 mV; Cummins and Waxman 1997) and 4 ms at −67 mV (Elliott and Elliott 1993) and one-quarter the recovery time constants for TTX-sensitive current in small DRG neurons (Everill et al. 2001).

In addition to the inactivation described above, NaV channels can enter into a distinct slow inactivated state, lasting seconds, which probably involves a different channel conformation (reviewed in Ulbricht 2005). NaV1.8 is unusual among NaV subunits for its rapid entry into slow inactivation from which it recovers slowly, even for relatively short depolarizations, contributing to adaptation of responses to physiological stimuli (Blair and Bean 2003). In our protocols probing recovery from inactivation (Fig. 7F, left), only ∼75% of INaR recovered with the fast time constant. The remainder of the recovery occurred with a slow time constant (1,060 ± 196 ms, n = 4), even for brief inactivating steps (Fig. 7F, right).

In summary, the properties of INaR are consistent with previous reports of current through NaV1.8 channels. As noted for INaI, it is very unlikely that CaV channels were involved, for similar reasons: INaR is carried by Na+, there was only trace Ca2+ in the external medium, and the voltage dependence and time course differed substantially from reported values for T-type (CaV3.1) Ca2+ currents, including T-type Ca2+ currents in immature mouse vestibular ganglion cells (Desmadryl et al. 1997; Chambard et al. 1999; Autret et al. 2005; Limón et al. 2005). Furthermore, the fast time constant for recovery from inactivation was much faster for INaR than for T-type current (1 ms at −90 mV, Fig. 7F, vs. 25–50 ms at −100 mV; Hering et al. 2004).

Size, Proportion, and Incidence of INaR

The average peak INaR was −2,962 ± 642 pA (n = 4; range −1,620 to −4,470 pA) or −109 ± 16.6 pA/pF in K+ internal and K+ external solutions and −1,978 ± 231 pA or −78 ± 9.4 pA/pF (n = 7) in Cs+ internal and Cs+ external solutions. Peak INaR conductance was 32.9 ± 4.0 nS and peak conductance density was 1.47 ± 0.25 nS/pF (n = 7; Cs+ internal and Cs+ external solutions). Since we excluded cells for which peak INaR was <15 times the residual (unblocked) outward current, these values may be larger than the true mean.

In five cells, we could segregate INaR and INaS pharmacologically by applying high doses of TTX to reveal INaR and subtracting to obtain INaS. In five other cells, we estimated the ratio of peak INaS to peak INaR by comparing peak INaV at −15 mV after a prepulse to −120 mV, which inactivated neither current, and after a prepulse to −40 mV, which inactivated INaS fully but INaR only by 15% (method illustrated in Fig. 7A1). To calculate proportions of each current, we corrected for the differences in percent maximal activation at the test voltage of −15 mV (100% for INaS vs. 76 ± 4%, n = 13, for INaR, Fig. 7B) and for the 15% inactivation of INaR at −40 mV. The method was validated by applying it to VGNs for which we also had pharmacological isolation of the currents, which showed that similar isolation was obtained (compare the red curves in Fig. 7, A2 and A3). The ratios of peak INaS to peak INaR did not differ significantly between data collected with and without TTX and were pooled, yielding a mean value of 3.8 ± 0.6 (range 1.8 to 7.5). Thus peak INaS was at least twice as large as INaR in a given cell. Peak current ratios may underestimate the relative influence of the TTX-resistant current, which, being slow, prolongs depolarization and its influence over other voltage-gated channels and calcium influx.

The incidence of INaR in our sample as a function of postnatal age increased rapidly from zero at P1 to ∼30% by P3–P4 (Fig. 5, hatched bars), in contrast to the decreasing incidence of INaI. Thus, by the latter part of the first postnatal week, approximately one-third of cells expressed INaI and INaS, one-third expressed INaR and INaS, and one-third expressed only INaS.

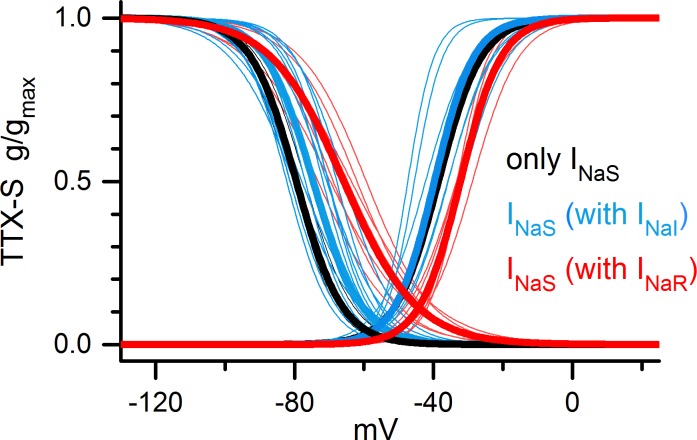

TTX-Sensitive Currents Differed Between VGNs With and Without TTX-Resistant Current

INaS was isolated by subtraction of records in 100–300 nM TTX from control records (0 TTX). INaS in VGNs with INaR differed from INaS in VGNs with INaI (Fig. 8 and Table 2) in size (about half) and voltage dependence: less negative (P = 0.005 for Vinact; P = 0.004 for Vact) and broader inactivation range (sinact, P = 0.0007) and was similarly distinct from INaS in cells with neither INaI nor INaR (Table 2). These differences might arise from the expression of different combinations of TTX-sensitive subunits, for which there are a number of candidates (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 8.

The TTX-sensitive current differed between cells with TTX-resistant current and cells without TTX-resistant current. INaS in VGNs with INaR (red) had a less negative voltage dependence and broader inactivation range than INaS in VGNs with only INaS (black), and in VGNs with INaI (blue). Thin lines, Boltzmann fits for individual cells; thick lines, mean curves. See Table 2 for Boltzmann parameters, numbers of cells in each group, and means ± SE.

In another difference, INaS showed use-dependent decline over the course of our standard voltage protocol in many VGNs with INaR but in no others. The ratio of peak INaS for the 1st vs. 24th sweeps in the protocol was significantly larger (1.28 ± 0.04) for 6 VGNs with INaR than for 15 cells lacking INaR (1.07 ± 0.04, P = 0.003). Use-dependent decline was described for TTX-sensitive currents in adult DRG cell bodies (Rush et al. 1998).

Firing Properties of Cells with INaR

Eighty VGNs were studied in current-clamp mode with more physiological solutions (K+ internal and modified L-15, Table 1) and no ion channel blockers. Current-clamp recordings were made immediately upon rupture to reduce possible effects of washout of endogenous molecules on firing patterns. After recording firing patterns, we switched to voltage-clamp mode and K+ external solution with K channel blockers and no added Ca2+ (Table 1) to determine whether INaR was present. INaR was recognized by its distinctive voltage and time dependence.

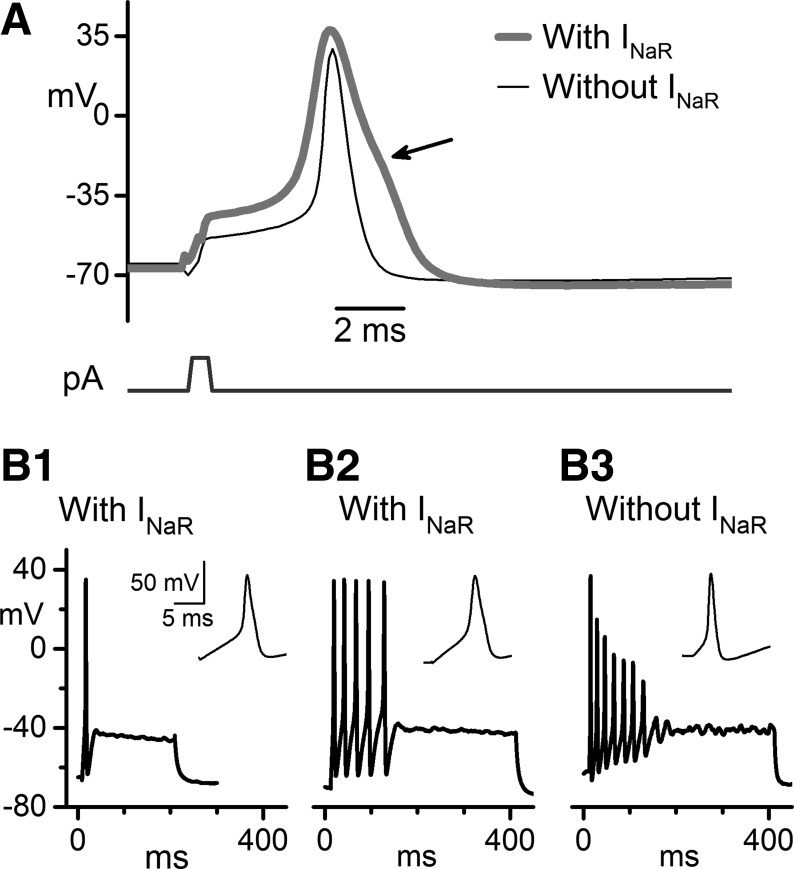

The most obvious differences in firing were between VGNs that expressed INaR (n = 11 VGNs) and VGNs that lacked INaR (n = 29 VGNs). Differences in other currents, including the differences in INaS described above, may contribute. Nevertheless, certain firing properties of VGNs with INaR resemble those in NaV1.8-expressing DRG neurons. The depolarized voltage dependence and fast recovery from inactivation of NaV1.8 channels are thought to contribute to tonic firing during sustained depolarizations. The slower time course produces broad spikes with an inflection or hump during the repolarization phase (reviewed in Rush et al. 2007). These features were observed in spikes from VGNs with INaR, as shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Spike shape and firing pattern differed between VGNs with INaR and VGNs without INaR. K+ internal, modified L-15 external. A: representative examples of voltage responses to 500-μs current steps are shown at firing threshold: 1,150 pA for a VGN with INaR and 400 pA for a VGN without INaR. VGNs with INaR had broader action potentials with less negative voltage thresholds and a shoulder during repolarization (arrow). Both cells: P7. Presence of INaR for each VGN was determined in voltage clamp after changing to K+ external with K channel blockers. B: firing patterns evoked by depolarizing current steps, 200 ms (B1) or 400 ms (B2, B3) long. VGNs with INaR fired either 1–2 spikes (B1) or multiple spikes (B2, B3). For multispiking VGNs, the presence of INaR was correlated with constant spike height throughout the train. Current steps of 160 pA (B1), 240 pA (B2), and 130 pA (B3) were selected to yield similar steady-state voltage. Insets: individual first spikes from the same trains. B1: P6. B2: P7. B3: P8. Scale bars in B1, including inset, apply to B2 and B3.

The current pulses we used to evoke action potentials were brief (500 μs) to minimize the influence of injected current on the action potential (Fig. 9A); large currents were required to achieve threshold with such brief pulses. The current amplitude was increased in 100-pA increments until a spike was evoked. The properties of this spike were compared for five VGNs with INaR and six VGNs without INaR at 23–25°C. The voltage threshold of the action potential (voltage at which dV/dt reached 4 mV/ms, chosen to be clearly above noise) was 10 mV less negative in cells with INaR (−44.2 ± 2.5 mV) than in cells without INaR (−53.8 ± 1.1 mV, P = 0.0003). The peak dV/dt on the upstroke of the action potential was twice as fast for cells without INaR (207 ± 24 mV/ms) than for cells with INaR (99 ± 11 mV/ms; P = 0.004). These differences may reflect the smaller size and less negative activation range of INaS in cells with INaR, combined with a strong contribution from INaR once voltage exceeds spike threshold. Spikes in VGNs with INaR were of similar height to, but broader than, spikes in VGNs without INaR (Fig. 9A). Spike height, measured from the spike peak to the afterhyperpolarization trough, was 105.5 ± 2.1 mV for cells with INaR and 102.9 ± 3.1 mV for cells without INaR. Spike width at half-height was ∼2–4 ms (2.64 ± 0.31 ms) for cells with INaR and ∼1 ms (1.07 ± 0.08 ms, P = 0.006) for cells without INaR. The slower kinetics and more depolarized voltage dependence of inactivation of INaR may broaden spikes, as reported in DRG and nodose ganglion neurons that have NaV1.8 current (Ritter and Mendell 1992; Djouhri et al. 2003). In addition to being broader, spikes in every VGN with INaR had a shoulder on the repolarization phase (n = 11 VGNs, Fig. 9A, arrow) while VGNs without INaR did not (n = 29). Although shoulders are often caused by Ca2+ currents, the slow properties of NaV1.8 current can contribute to shoulders (Ritter and Mendell 1992; Cardenas et al. 1997). In DRG neurons with NaV1.8 channels, ∼60% of the current during the shoulder flows through NaV1.8 channels, with the rest mostly through high-voltage CaV channels (Blair and Bean 2002).

The current threshold for spiking evoked by longer current steps (Fig. 9B) delivered in 10-pA increments was +30 ± 4 pA in 4 VGNs with INaR and +24 ± 5 pA in 24 VGNs without INaR (NS, P = 0.32). The firing patterns of VGNs in response to depolarizing current steps have been subdivided into “transient” or “single-spiker” (1–2 spikes at the start of the current step) and “sustained” or “multispiker” (Iwasaki et al. 2008; Kalluri et al. 2010). It is hypothesized that transient patterns are typical of irregularly firing afferents from central epithelial zones and sustained patterns are made by regularly firing afferents from peripheral epithelial zones (Iwasaki et al. 2008; Kalluri et al. 2010). In our limited dataset, we did not see a simple correlation between INaR and either the “transient” or “sustained” firing pattern. In VGNs with INaR (n = 11), firing patterns ranged from a single spike (Fig. 9B1) to multiple spikes that terminated before the end of the step (Fig. 9, B2 and B3): none showed a fully sustained response that lasted the duration of the step. In all six multispiking VGNs with INaR, successive spikes were of similar height until spiking abruptly stopped (Fig. 9B2), in contrast to the decrementing spikes of multispiking VGNs without INaR (n = 24) (Fig. 9B3). A possible reason for the abrupt termination is accumulating inactivation of TTX-sensitive currents. Because of their more negative activation range, TTX-sensitive currents may dominate the initial phase of the spike around threshold, but TTX-resistant currents should contribute strongly later in the spike (Blair and Bean 2002). In this way, inactivation of TTX-sensitive currents may increase spike threshold until spiking stops without much affecting spike height.

Despite a significant overlap of activation and inactivation ranges (a “window current”), the activation range of INaR was positive relative to most resting potentials. Mean resting potentials were −68.2 ± 2.1 mV (n = 6) for cells with INaR and −71.6 ± 0.7 mV (n = 26) for cells without INaR (P = 0.19). Thus the transient component of the current played little role in resting potential in these isolated neurons, although persistent current might (Han et al. 2015). We observed only two spontaneously firing VGNs in this study, neither of which had INaR.

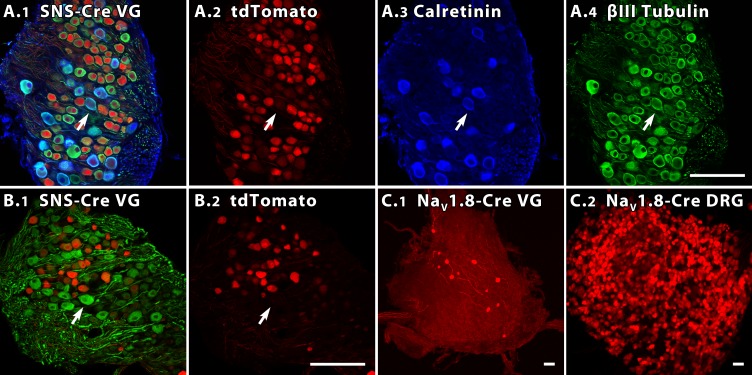

Nav1.8 Expression in Reporter Mice

Our electrophysiological data suggest that TTX-resistant currents carried by NaV1.8 channels are expressed by a VGN subpopulation that also differs from other neurons in the properties of TTX-sensitive current and spikes. To visualize this subpopulation, we examined the vestibular ganglia of two mouse lines in which cells that expressed NaV1.8 (SNS) also expressed the red fluorescent protein tdTomato (see materials and methods). We refer to the BAC transgenic line as SNS-Cre (Agarwal et al. 2004) and the targeted knockin as NaV1.8-Cre (Stirling et al. 2005).

Confocal images in Fig. 10 illustrate the tdTomato signal in three vestibular ganglia and one DRG. Figure 10A1 shows an SNS-Cre/Rosa26LSL-tdTomato vestibular ganglion also immunostained for calretinin, which is selectively expressed by calyx-only afferents, and β-III tubulin, which labels most VGNs (Perry et al. 2003). The staining patterns for tdTomato, calretinin, and β-III tubulin for this section are shown individually in Fig. 10, A2-A4. Figure 10B1 shows a second SNS-Cre vestibular ganglion with tdTomato and immunostaining for the heavy neurofilament NF200; Fig. 10B2 is the same section showing tdTomato alone. NF200-like immunoreactivity is strongest in large VGN somata (Ylikoski et al. 1990; Usami et al. 1993a,b), similar to the pattern in the DRG (Lawson and Waddell 1991). tdTomato expression was largely nonoverlapping with intense immunostaining in large VGNs for calretinin and for NF-200; arrows point to an exemplar large VGN that is positive for calretinin (tissue in Fig. 10A) or NF200 (tissue in Fig. 10B) but not tdTomato.

Fig. 10.

In 2 NaV1.8 reporter mouse lines, different percentages of vestibular ganglion neurons are labeled. A and B: 35-μm sections from the superior vestibular ganglia (VG) of 4- to 6-wk SNS-Cre reporter mice, showing tdTomato (red) in many VGNs. Scale bars (50 μm) in A4 and B2 apply to A1-A4 and B1-B2. A1: SNS-Cre VG colabeled with antibodies to calretinin (blue) and β-III tubulin (green). A2-A4: color channels of A1 shown separately. Calretinin-positive cells (A3) are relatively large and not tdTomato-positive (e.g., arrow). B1: SNS-Cre section from a different mouse, colabeled with NF200 antibody (green). Intensely NF200-positive cells (e.g., arrow) are often large and not tdTomato-positive. B2: same section showing tdTomato alone. C: tdTomato expression in VG (C1) and DRG (C2) of a 5- to 6-wk NaV1.8-Cre reporter mouse. Scale bars = 50 μm. C1: maximum intensity projection image of the VG. C2: whole mount DRG from the same animal. Despite strong tdTomato label in the DRG, fewer VGNs are positive in this reporter line than in the SNS-Cre mouse.

In vestibular ganglia of the NaV1.8-Cre mouse line, far fewer neurons were tdTomato-positive (Fig. 10C1), although DRGs from the same animals (Fig. 10C2) had many tdTomato-positive neurons, as did DRGs in the SNS-Cre line (not shown). Differences between transgenic and knockin reporter lines are not unexpected; which is more representative of NaV1.8 expression requires more study.

DISCUSSION

NaV Channel Diversity in the Vestibular Ganglion

As reported previously, rodent vestibular ganglion cell bodies have large TTX-sensitive currents (Chabbert et al. 1997; Risner and Holt 2006). A closer look has uncovered heterogeneity. RT-PCR of whole vestibular ganglia revealed mRNA expression of all known NaV channel subunits, including TTX-insensitive and TTX-resistant α-subunits. Whole cell recordings then provided evidence for functional expression of multiple NaV currents.

In acutely dissociated VGNs between P3 and P8, before maturation of the inner ear, we isolated TTX-insensitive and TTX-resistant currents that resembled currents carried by NaV1.5 and NaV1.8 α-subunits, respectively, in their kinetics and pharmacology. The expression of these subunits was further supported by NaV1.5-like immunoreactivity and by labeling in two kinds of Nav1.8 reporter mice. Whole cell recordings suggest that NaV1.5 current is widely expressed in neonatal afferent cell bodies but declines over the first postnatal week, while NaV1.8 is upregulated in some VGNs over the same period. We further found that the TTX-sensitive Na+ currents are heterogeneous, having smaller amplitude, less negative voltage dependence, and less steep voltage dependence of inactivation in VGNs with TTX-resistant current than in other VGNs. The RT-PCR results suggest multiple candidates for the pore-forming α-subunits that carry TTX-sensitive currents, and it is possible that VGNs with TTX-resistant current express a different complement of TTX-sensitive subunits than VGNs without TTX-resistant current. Differences in β-subunit expression also affect properties of TTX-sensitive currents (Namadurai et al. 2015). A likely contributor to TTX-sensitive current in vestibular afferents is the NaV1.6 subunit, which is expressed at the afferent heminode adjacent to hair cell synapses (Hossain et al. 2005; Lyakowski et al. 2011).

Expression of Nav1.8 in Peripheral Sensory Neurons