Abstract

Impairments in human motor patterns are complex: what is often observed as a single global deficit (e.g., limping when walking) is actually the sum of several distinct abnormalities. Motor adaptation can be useful to teach patients more normal motor patterns, yet conventional training paradigms focus on individual features of a movement, leaving others unaddressed. It is known that under certain conditions, distinct movement components can be simultaneously adapted without interference. These previous “dual-learning” studies focused solely on short, planar reaching movements, yet it is unknown whether these findings can generalize to a more complex behavior like walking. Here we asked whether a dual-learning paradigm, incorporating two distinct motor adaptation tasks, can be used to simultaneously train multiple components of the walking pattern. We developed a joint-angle learning task that provided biased visual feedback of sagittal joint angles to increase peak knee or hip flexion during the swing phase of walking. Healthy, young participants performed this task independently or concurrently with another locomotor adaptation task, split-belt treadmill adaptation, where subjects adapted their step length symmetry. We found that participants were able to successfully adapt both components of the walking pattern simultaneously, without interference, and at the same rate as adapting either component independently. This leads us to the interesting possibility that combining rehabilitation modalities within a single training session could be used to help alleviate multiple deficits at once in patients with complex gait impairments.

Keywords: adaptation, locomotion, motor learning, dual task, interference

for our most practiced and stereotyped movements, we rely on adaptive learning to remain flexible in how we move. Whether walking (Reisman et al. 2005), reaching (Shadmehr and Mussa-Ivaldi 1994), or moving the eyes (Wallman and Fuchs 1998), the nervous system responds to external perturbations by attempting to reduce the errors from one movement to the next (Bastian 2008). This capability to rapidly adjust movements is essential to account for our highly variable environments and can be leveraged for rehabilitation to overcome motor deficits. For instance, walking on a split-belt treadmill, where one treadmill belt is moved faster than the other, leads to locomotor adaptation, which can improve the symmetry of walking in patients poststroke (Reisman et al. 2007, 2013). Likewise, wearing prism goggles (specialized goggles that shift the entire visual field laterally or vertically) induces a visuomotor adaptation that can improve symptoms of hemispatial neglect in chronic stroke patients (Rossetti et al. 1998).

When one considers adaptation as a potential rehabilitative treatment, one drawback of commonly used paradigms is they target only one specific feature of the movement. For instance, the aforementioned split-belt treadmill adaptation paradigm primarily alters step length symmetry. After stroke, however, disruption of a global behavior like walking is typically exhibited as a combination of multiple local abnormalities rather than a single global deficit. In addition to step length asymmetry, stroke survivors also frequently demonstrate decreased paretic knee flexion, resulting in a “circumducted” leg swing pattern (Kerrigan et al. 2000). This abnormality may be caused by several factors, including increased knee extensor muscle tone (Kerrigan et al. 1991; Sutherland et al. 1990; Waters et al. 1979) or weakness of the hip flexor (Kerrigan et al. 1991, 1998; Riley and Kerrigan 1998), and is not influenced by split-belt training (Reisman et al. 2005). Therefore, additional training paradigms are necessary to target paretic joint flexion to compensate fully for the complex gait problems experienced by these patients.

Under certain conditions, it is possible to adapt multiple, distinct movement characteristics simultaneously. Krakauer and colleagues (1999) demonstrated that in reaching movements, as long as two perturbations depended on different parameters of the movement (e.g., hand position and acceleration), they can be adapted concurrently without interference. Along these lines, Summa et al. (2012) recently showed that simultaneous reaching adaptation to both a force-field and a visuomotor rotation can occur in parallel, with little interaction, and at similar rates. These results have important implications when applied to rehabilitation of the complex movement deficits, such as gait impairments, experienced by stroke patients. However, it has yet to be determined whether this type of dual-learning paradigm can be effective in the context of walking, or whether it can be used to modify movement characteristics that are clinically important.

Here we asked whether a dual-learning paradigm can be used to simultaneously adapt multiple components of the walking pattern. We developed a joint-angle learning task that used biased visual feedback of sagittal joint angles to alter peak knee or hip flexion angles during the swing phase of the gait cycle. Young, healthy participants performed this task either independently or concurrently with split-belt treadmill walking (i.e., dual-learning). We hypothesized that the dual-learning paradigm would lead to adaptive changes in both step length symmetry and peak sagittal joint angles, two essential features of the walking pattern commonly impaired poststroke, and these changes would occur independently, without interference, and at a similar rate as adapting each parameter separately.

METHODS

We conducted two experiments with healthy adults that had no known neurological disorders. Eighteen healthy, naïve subjects (9 men, 26 ± 4 yr old) participated in Experiment 1, and 27 additional subjects (9 men, 24 ± 4 yr old) in Experiment 2. The experimental protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before testing.

Split-belt treadmill.

Participants walked on a custom split-belt treadmill (Woodway USA, Waukesha, WI) capable of moving each leg at different speeds. Subjects in Experiment 1 walked with “tied-belts” only, where both belts moved the same speed for the duration of the experiment, and subjects in Experiment 2 walked with periods of “split-belts,” where the belts moved different speeds. Speed commands for each belt were sent to the treadmill through a custom Python program in the Vizard (WorldViz) development environment. Subjects were positioned with one leg on each treadmill belt and wore a safety harness. They also held onto a handrail in front of the treadmill for all phases of the experiments to simulate the conditions that we would want to use in the future when training stroke patients on a split-belt treadmill.

Optotrak motion analysis.

Kinematic data were collected during walking at 100 Hz using Optotrak (Northern Digital, Waterloo, ON, Canada). Infrared-emitting markers were placed bilaterally on the fifth metatarsal head (toe), lateral malleolus (ankle), lateral femoral epicondyle (knee), greater trochanter (hip), iliac crest (pelvis), and acromion process (shoulder). Limb angle was defined as the angle between a vertical line and the vector from the hip to the toe on an x/y-plane. Limb angle is positive during flexion when the foot is in front of the hip and negative when the foot is behind the hip. Heel strike times were approximated using the maximum (positive) angle of the limb, and toe-off was approximated as the minimum (negative) limb angle (Malone and Bastian 2014).

Joint-angle learning task.

We explored the effects of a novel joint-angle feedback task to teach subjects new peak sagittal joint-angle patterns during walking (Fig. 1A). Subjects were provided real-time visual feedback of their knee or hip (depending on group assignment) flexion angles during walking using a custom Python program that was synchronized with Optotrak software to sample marker position simultaneously. Knee flexion angle was calculated as the angle between the vector from the hip to the knee and the vector from the knee to the ankle; increasing positive values indicated increased flexion. Hip flexion angle was calculated as the angle between a vertical reference passing from the hip joint to the floor and the vector from the hip to the knee. Here again increasing positive values indicated increased flexion. Visual feedback was provided as a green bar that increased or decreased in height based on real-time changes in knee or hip flexion angle. Subjects were additionally provided a “target” line for each leg and were instructed to walk such that their peak knee or hip flexion, occurring during the swing phase of the stride cycle, was as close to the target as possible.

Fig. 1.

A: diagram of joint-angle learning task. Participants were provided real-time visual feedback of knee or hip flexion angles during walking in the form of green bars that changed in height based on changes in joint flexion. Target lines were provided based on each subject's baseline peak flexion patterns. Subjects were instructed to walk such that the height of the green bar on each leg was within the target line each stride. Target lines remained in the same location throughout the experiment. During Adaptation, however, feedback for the left leg was offset by −10°. To successfully reach the target line, participants were thus required to increase joint flexion on the left leg. Optotrak marker locations are indicated by blue circles. Knee flexion angle was calculated as the angle between the vector from the hip to the knee and the vector from the knee to the ankle. Hip flexion angle was calculated as the angle between a vertical reference passing from the hip joint to the floor and the vector from the hip to the knee. For either joint, increasing positive values indicated increased flexion. B: example hip flexion angles for a single stride cycle plotted as a function of time during baseline and late adaptation. Positive values indicate flexion and negative values indicate extension. Peak flexion angles for each leg are highlighted. During baseline, hip flexion difference (left − right peak hip flexion) is roughly 0. By late adaptation, hip flexion difference increases due to greater peak left hip flexion.

Experiment 1: joint-angle learning.

Subjects in Experiment 1 were randomly divided into two groups that were given feedback on either knee flexion angle (Knee Feedback group) or hip flexion angle (Hip Feedback group). The experimental paradigm consisted of five walking phases (Fig. 2A), as follows: Baseline 1, all subjects walked for 1 min with no visual feedback; Baseline 2, subjects walked for 2 min with unbiased (i.e., veridical) feedback such that the target lines represented the mean peak knee or hip flexion angle during Baseline 1 walking (i.e., mean of both legs during Baseline 1); Baseline 3, subjects walked for an additional 2 min with no visual feedback; Adaptation, subjects walked for 15 min with visual feedback. During this phase, the target lines for both legs were in the same location as previously seen in Baseline 2; however, an offset of −10° was applied to the left leg feedback. Successfully performing the task (i.e., reaching the target lines with the joint feedback) thus required participants to flex the left knee or hip 10° more than at baseline. We initially found that participants receiving hip flexion feedback had difficulty actively coordinating the flexion of both hips with the feedback; therefore, to simplify the task subjects in the Hip Feedback group were provided feedback of the left hip only, allowing the right hip to move freely. The Knee Feedback group received feedback of both legs. Despite this slight alternation in the experimental conditions between the groups, the effect of the visual feedback was the same: participants in both cases were required to flex the left knee or hip an additional 10°, while the right knee/hip flexed normally; Postadaptation, subjects walked for 15 min with no visual feedback to assess any aftereffects of the Adaptation phase (i.e., how subjects unlearn the new joint-angle pattern). All subjects walked with tied-belts (both treadmill belts set at 1.0 m/s) during each phase of the experiment.

Fig. 2.

Experimental paradigm for Experiment 1 (A) and Experiment 2 (B). Hip or knee flexion feedback was provided during Baseline 2 and Adaptation phases, shown in gray. No feedback (FB) was provided during all other phases, shown in white. Participants in Experiment 1 walked with tied-belts (1.0 m/s) throughout the experiment. The paradigm for Experiment 2 differed only in that participants walked with split-belts (left belt 0.5 m/s, right belt 1.5 m/s) during Adaptation. Knee Feedback and Hip Feedback groups participated in Experiment 1, whereas Split Only, Split + Knee Feedback, and Split + Hip Feedback groups participated in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2: dual-learning: joint-angle with split-belt adaptation.

The experimental paradigm for Experiment 2 paralleled that of Experiment 1, except that subjects simultaneously adapted to a split-belt treadmill while performing the joint-angle learning task (Fig. 2B). Specifically, during the Adaptation phase the left (“slow”) treadmill belt moved at 0.5 m/s and the right (“fast”) belt moved at 1.5 m/s. The left belt was designated as the “slow” belt to correspond with the leg adapting to joint-angle feedback. During split-belt training in stroke patients, the paretic leg is generally placed on the “slow” belt (Reisman et al. 2010; Roemmich et al. 2012) and would benefit from joint-angle adaptation, so we designed the paradigm in this manner to best represent the conditions we anticipate would be most beneficial to stroke rehabilitation. Subjects were randomly divided into three groups that were provided either no visual feedback during Adaptation (Split Only group), knee flexion feedback (Split + Knee Feedback group), or hip flexion feedback (Split + Hip Feedback group). As in Experiment 1, the feedback groups received a visual perturbation of −10° on the feedback for the left leg. All other phases of the experiment consisted of tied-belt walking at 1.0 m/s with either no feedback (Baseline 1, Baseline 3, Postadaptation) or unbiased (i.e., veridical) feedback (Baseline 2).

Data analysis.

Kinematic data were analyzed stride-by-stride to calculate the peak hip (HF) or knee flexion (KF) angle during each stride cycle. Our primary outcome measures for the joint-angle learning task were knee flexion difference and hip flexion difference during each stride cycle, defined as the difference between the left and right legs' (or “slow” and “fast,” respectively, for Experiment 2) peak knee or hip flexion angle each stride (Fig. 1B), or:

| (1) |

| (2) |

A value of 0 indicates symmetric peak joint flexion between the legs, while positive values indicate that the left leg had greater peak flexion than the right leg and vice versa for negative values.

In Experiment 2, we additionally analyzed step length symmetry, which has previously been shown to adapt robustly to split-belt treadmill walking (Reisman et al. 2005). Step symmetry was defined as the normalized difference between the step lengths (SL) of the “fast” and “slow” leg, or:

| (3) |

We normalized the data so subjects of different heights who take different sized steps could be compared. A value of 0 indicates symmetric walking, while positive values indicate that the fast step was larger than the slow step and vice versa for negative values.

We characterized the learning and unlearning patterns of all three parameters (step symmetry, knee flexion difference, hip flexion difference) by computing the average values of each parameter across distinct time epochs during each experiment: baseline (mean of Baseline 3), early adaptation (first 5 strides of Adaptation), adaptation plateau (last 100 strides of Adaptation), early postadaptation (first 5 strides of Postadaptation), and postadaptation plateau (last 100 strides of Postadaptation). Additionally, the time courses of learning and unlearning were determined by computing the number of strides from the beginning of each phase until the respective parameter remained within the plateau range for 30 strides. The plateau range was defined as the mean ± 2 SDs of the plateau (Finley et al. 2014).

Statistics.

To confirm that no differences existed in baseline walking between the groups, we first performed an independent-samples t-test (Experiment 1) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; Experiment 2) to compare baseline performance in each walking parameter (step symmetry, knee flexion difference, and hip flexion difference). In Experiment 1, we used single-samples t-tests to determine if the knee or hip flexion difference values were significantly different from 0.

To investigate differences among groups during learning and unlearning in Experiment 2, we used separate one-way ANOVAs for each walking parameter during the aforementioned time epochs (early adaptation, adaptation plateau, early postadaptation, postadaptation plateau, and the number of strides to reach plateau). When applicable, post hoc analysis was performed using the Bonferroni test. To best visualize the results in the figures, data were smoothed with a moving average and binned by three strides; however, statistics were performed on the unsmoothed data. Additionally, the Knee Feedback and Hip Feedback groups from Experiment 1 were included in the analysis of Experiment 2 to compare joint-angle learning alone to dual-learning performance. When we describe Experiment 2 results, they are referred to as the Knee Feedback Only and Hip Feedback Only groups, respectively. We tested whether the step symmetry values for these two groups were different from 0 using single-samples t-tests.

RESULTS

All subjects were able to complete the walking tasks without difficulty regardless of group assignment. All groups walked similarly at baseline; we did not observe any significant differences between groups in any walking parameter (step symmetry, knee flexion difference, hip flexion difference; all P > 0.05). We therefore subtracted the baseline values of each parameter from all data to best visualize the results.

Experiment 1: joint-angle learning task leads to adaptation and motor aftereffects in both knee and hip flexion angles.

In general, we saw that the biased joint-angle feedback provided during the adaptation phase of Experiment 1 had the effect of increasing the peak flexion angle of the desired joint, resulting in increased knee/hip flexion difference. We first examined the effect of each feedback condition (knee or hip flexion feedback) on that specific joint [i.e., the effect of knee flexion feedback on knee flexion difference (Fig. 3A), and the effect of hip flexion feedback on hip flexion difference (Fig. 3D)]. By the end of adaptation, participants in the Knee Feedback group exhibited a significant increase in knee flexion difference compared with 0 (plateau: 8.00 ± 0.76°, P < 0.001). Similarly, the Hip Feedback group demonstrated a significant increase in hip flexion difference compared with 0 (plateau: 8.78 ± 0.68°, P < 0.001). Subjects in the Hip Feedback group additionally exhibited an immediate increase in hip flexion difference during early adaptation (5.14 ± 0.52°, P < 0.001), though the Knee Feedback group did not (knee flexion difference: 0.12 ± 1.83°, P = 0.951).

Fig. 3.

Peak sagittal joint angles plotted stride-by-stride for Experiment 1. Data from the joint for which we gave feedback (i.e., knee flexion difference for Knee Feedback group, and hip flexion difference for Hip Feedback group) are shown in red (A, D). Data for other joint are shown in black (B, C). Symmetric peak joint flexion between the legs is indicated by 0, while positive values indicate that the left leg had greater peak flexion than the right leg and vice versa for negative values. Baseline 3, Adaptation, and Postadaptation phases are displayed. Data are smoothed with a running average by 3 strides and expressed relative to baseline. Shaded areas around each line represent SE.

Importantly, both feedback conditions led to significant motor aftereffects during postadaptation. During early postadaptation, subjects in the Knee Feedback group demonstrated significantly greater knee flexion difference compared with 0 (3.38 ± 0.57°, P < 0.001). The same was true for hip flexion difference in the Hip Feedback group (2.96 ± 0.85°, P = 0.008). Both groups returned to baseline values by the end of postadaptation (Knee Feedback group/knee flexion difference: 0.51 ± 0.50°, P = 0.331; Hip Feedback group/hip flexion difference: 0.21 ± 0.52°, P = 0.702).

We were additionally interested in seeing how knee flexion feedback affected kinematics of the hip joint (Fig. 3B) and vice versa (Fig. 3C), so we repeated our analysis for each group with the alternate joint. Results paralleled those from our original analysis, indicating that adaptation from knee or hip feedback affects both joints rather than being specific to the task goal. Specifically, the Knee Feedback group exhibited a significant increase in hip flexion difference in the adaptation plateau (5.85 ± 0.38°, P < 0.001) and early postadaptation (1.89 ± 0.49°, P = 0.005). Similarly the Hip Feedback group demonstrated a significant increase in knee flexion difference in the adaptation plateau (12.25 ± 1.37°, P < 0.001) and early postadaptation (4.73 ± 1.00°, P = 0.002), as well as early adaptation (5.18 ± 0.98°, P = 0.001). Together, the results from Experiment 1 indicate that knee or hip flexion feedback can be used teach subjects a new walking pattern with increased knee and hip flexion, and this new walking pattern is temporarily stored and must be unlearned upon removal of the feedback.

Experiment 2: dual-learning task leads to simultaneous adaptation of joint flexion angles and step symmetry without interference.

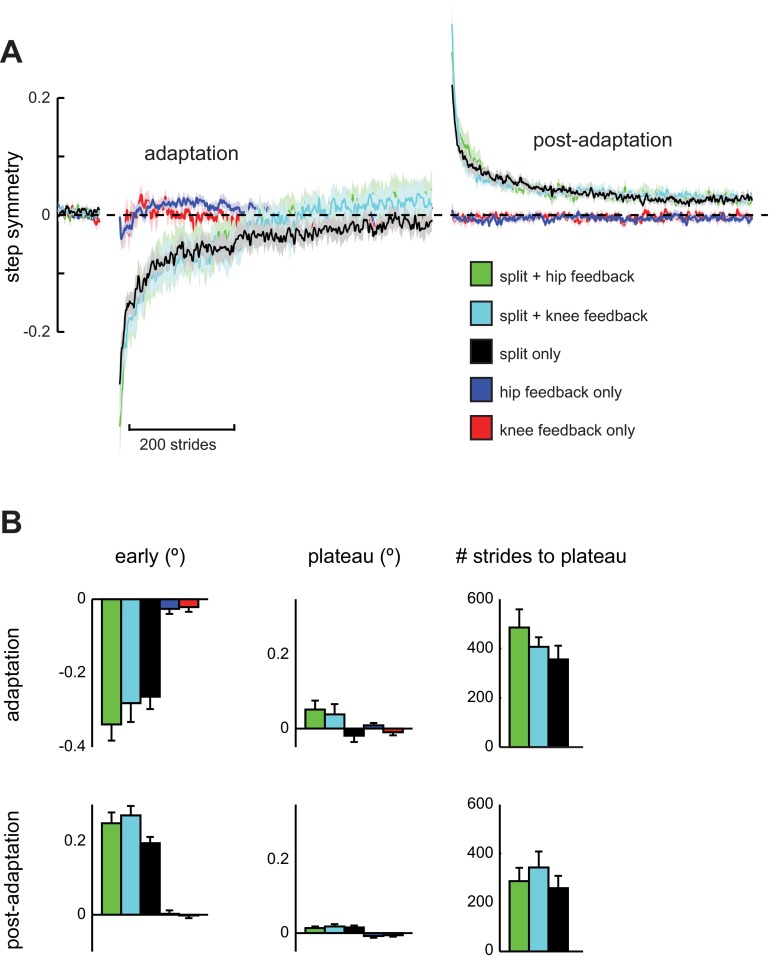

Subjects in Experiment 2 performed a dual-learning task that incorporated the joint-angle learning task together with split-belt treadmill adaptation. We were interested in determining whether this dual-learning task interfered with subjects' ability to perform either task, or if these separate kinematic features of the walking pattern could be learned simultaneously. We first observed that joint-angle adaptation alone did not significantly alter step symmetry during any time epoch (all P > 0.05) in either the Knee Feedback Only (previously the Knee Feedback group from Experiment 1) or Hip Feedback Only group (previously the Hip Feedback group from Experiment 1). Next, we compared changes in step symmetry between the Split Only, Split + Knee Feedback, and Split + Hip Feedback groups to assess possible interference of joint-angle adaptation with split-belt adaptation (Fig. 4). During the adaptation phase, there were no significant group differences in step symmetry for early adaptation [F(2,26) = 0.813, P = 0.455], plateau [F(2,26) = 2.600, P = 0.095] or number of strides to reach plateau (i.e., rate of adaptation) [F(2,26) = 1.279, P = 0.297]. Similarly, we found no significant differences for early postadaptation [F(2,26) = 2.508, P = 0.103], postadaptation plateau [F(2,26) = 0.169, P = 0.845], or de-adaptation rate [F(2,26) = 0.569, P = 0.574]. These results demonstrate that performance of the dual-learning task with either knee or hip flexion feedback did not significantly interfere with participants' ability to adapt or de-adapt step symmetry during split-belt treadmill walking.

Fig. 4.

Step symmetry results for Experiment 2. A: step symmetry plotted stride-by-stride for Split + Hip Feedback (green), Split + Knee Feedback (light blue), Split Only (black), Hip Feedback Only (dark blue), and Knee Feedback Only (red) groups. Symmetric walking is indicated by 0, while positive values indicate that the fast step was larger than the slow step and vice versa for negative values. Data are smoothed with a running average by 3 strides and expressed relative to baseline. Shaded areas around each line represent SE. B: comparison of group step symmetry during early Adaptation and Postadaptation, plateau levels, and the number of strides required to reach plateau. Data shown as means ± SE.

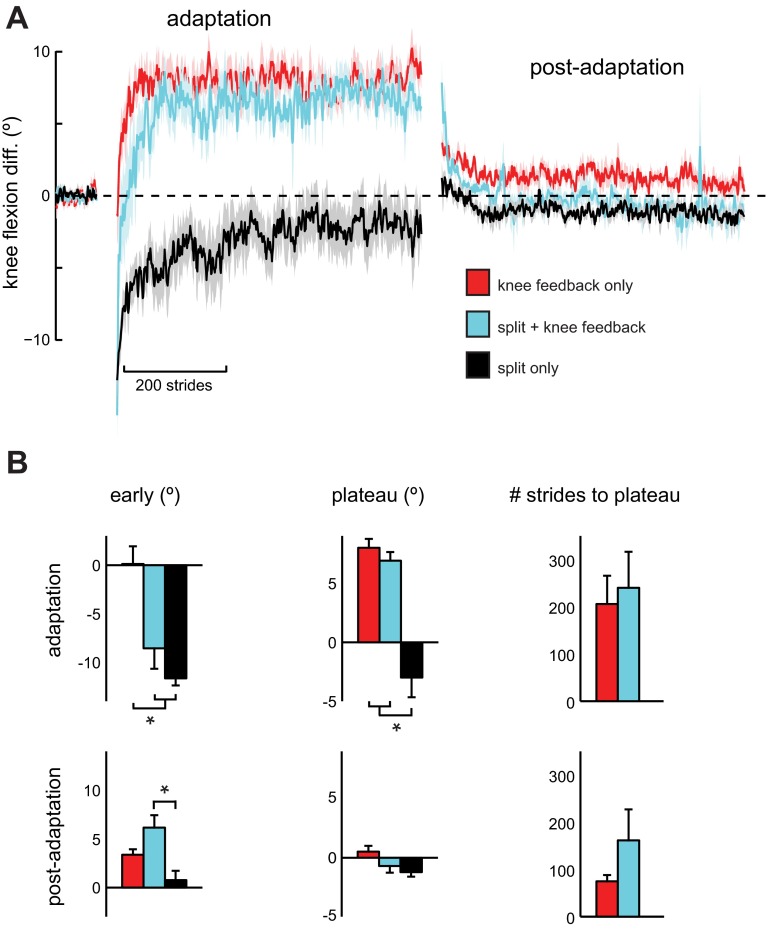

Like step symmetry, we found that the dual-learning task did not interfere with performance of the joint-angle learning tasks. To assess this, we first compared changes in knee flexion difference between the Knee Feedback Only, Split Only, and Split + Knee Feedback groups (Fig. 5). Results from our ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group on early adaptation [F(2,26) = 13.363, P < 0.001] and the plateau level [F(2,26) = 28.049, P < 0.001]. Post hoc analysis demonstrated that both the Split Only and Split + Knee Feedback groups had significantly lower knee flexion difference than the Knee Feedback Only group in early adaptation (P = 0.004 and P < 0.001, respectively), suggesting that knee flexion pattern was initially driven by the split-belt perturbation during the early part of the dual-learning task. Over the course of adaptation, however, the Split + Knee Feedback group was able to learn the new knee flexion pattern and reached a similar plateau level compared with the Knee Feedback Only group (P = 1.000). At this point, both feedback groups differed significantly from the Split Only group (both groups P < 0.001). Additionally, the Knee Feedback Only and Split + Knee Feedback groups had similar rates of knee flexion difference adaptation (P = 0.727). Our ANOVA for the postadaptation period revealed a significant effect of group on early postadaptation [F(2,26) = 7.682, P = 0.003]. In contrast to early adaptation when the dual-learning task resulted in an initial knee flexion difference similar to that of the Split Only group, the Split + Knee Feedback group now exhibited a significant increase in early postadaptation compared with the Split Only group (P = 0.002) and was not significantly different from the Knee Feedback Only group (P = 0.162). The two feedback groups had similar rates of de-adaptation of knee flexion difference (P = 0.227).

Fig. 5.

Knee flexion difference results for Experiment 2. A: knee flexion difference plotted stride-by-stride for Knee Feedback Only (red), Split + Knee Feedback (light blue), and Split Only (black) groups. Symmetric peak knee flexion between the legs is indicated by 0, while positive values indicate that the left knee had greater peak flexion than the right knee and vice versa for negative values. Data are smoothed with a running average by 3 strides and expressed relative to baseline. Shaded areas around each line represent SE. B: comparison of group knee flexion difference during early Adaptation and Postadaptation, plateau levels, and the number of strides required to reach plateau. Data shown as means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

We performed the same analysis for hip flexion difference between the Hip Feedback Only, Split Only, and Split + Hip Feedback groups and found very similar results (Fig. 6). During the adaptation phase, our ANOVA showed a significant effect of group on early adaptation [F(2,26) = 33.898, P < 0.001] and the plateau level [F(2,26) = 48.843, P < 0.001]. As previously seen with knee flexion difference, post hoc analysis revealed that both the Split Only and Split + Hip Feedback groups had lower hip flexion difference than the Hip Feedback Only group in early adaptation (both groups P < 0.001), indicating that early adaptation behavior was driven more by the split-belt perturbation during the dual-learning task. However, the Split + Hip Feedback group successfully learned the new hip flexion pattern during adaptation and reached a similar plateau level compared with the Hip Feedback Only group (P = 0.362), with each group significantly different from the Split Only group (both groups P < 0.001). The Hip Feedback Only and Split + Hip Feedback groups learned the new hip flexion pattern at a similar rate (P = 0.819). Analysis for postadaptation showed a similar trend seen in the knee flexion difference, but hip flexion results were not quite significant. Specifically, our ANOVA revealed a trend toward a group effect during early postadaptation [F(2,26) = 3.316, P = 0.054], with the Hip Feedback Only and Split + Hip Feedback groups more similar to each other (P = 1.000) rather than the Split Only group (Hip Feedback Only: P = 0.144; Split + Hip Feedback: P = 0.099). However, these results were not statistically significant. Lastly, the two feedback groups had similar rates of de-adaptation of hip flexion difference (P = 0.952).

Fig. 6.

Hip flexion difference results for Experiment 2. A: hip flexion difference plotted stride-by-stride for Hip Feedback Only (dark blue), Split + Hip Feedback (green), and Split Only (black) groups. Symmetric peak hip flexion between the legs is indicated by 0, while positive values indicate that the left hip had greater peak flexion than the right hip and vice versa for negative values. Data are smoothed with a running average by 3 strides and expressed relative to baseline. Shaded areas around each line represent SE. B: comparison of group hip flexion difference during early Adaptation and Postadaptation, plateau levels, and the number of strides required to reach plateau. Data shown as means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

In both knee flexion difference and hip flexion difference, we additionally found significant or nearly significant effects of group for the postadaptation plateau level (representing return to “baseline”) [knee flexion difference: F(2,26) = 3.380, P = 0.051; hip flexion difference: F(2,26) = 3.521, P = 0.046]. These postadaptation plateau results are largely driven by a slightly decreased plateau in the Split Only group; therefore, we do not believe they are indicative of any residual effects of the feedback on knee or hip flexion.

Together, the results from Experiment 2 demonstrate that step symmetry and knee/hip flexion difference can be adapted simultaneously and without interference in a single session using a dual-learning paradigm.

DISCUSSION

Here we asked whether two distinct components of the walking pattern can be learned simultaneously, or if they interfere with one another. Concurrent learning of separate movement components without interference was previously shown in planar reaching movements (Krakauer et al. 1999); however, we were interested in determining if this finding would generalize to a more complex, real-world behavior like walking. We first showed that biased visual feedback alone can lead to adaptation of peak knee and hip flexion angles during the swing phase of walking. Next, we demonstrated that performing this joint-angle adaptation task concurrently with split-belt treadmill walking leads to simultaneous adaptation of knee/hip flexion angles and step length symmetry without interference, and at the same rate as adapting each component individually.

It was important to determine initially whether biased visual feedback alone can induce adaptation of peak sagittal joint angles during walking. It was recently shown that a similar visual feedback paradigm can lead to adaptation of the temporal aspects of interlimb coordination during walking, particularly swing times (Hussain et al. 2013). How this would translate to the intralimb kinematics studied here, however, was unknown. Specifically, we were unsure whether participants would truly adapt their walking patterns in response to visual feedback errors or simply make a conscious adjustment to knee or hip flexion to accomplish the task goals. An important characteristic in differentiating conscious adjustment of movement and motor adaptation is that after adaptation, individuals exhibit motor aftereffects and must actively de-adapt their behavior back to the original state (Bastian 2008). After the participants were exposed to biased visual feedback for a period of 15 min, the removal of feedback resulted in motor aftereffects consistent with those seen in previous locomotor adaptation studies (Torres-Oviedo et al. 2011). Our joint-angle learning task, then, likely created a visually driven sensory prediction error (Tseng et al. 2007) that provoked subsequent motor adaptation.

The main result of this study is that two distinct parameters of the walking pattern can be adapted simultaneously and without interference. It should be noted that our goal was not to study the effect of divided attention using a “dual-task,” as is commonly done combining a motor and cognitive task (Li et al. 2012; Malone and Bastian 2010; Taylor and Thoroughman 2007). These types of dual-task studies generally demonstrate interference in the amount (Taylor and Thoroughman 2007) or rate (Malone and Bastian 2010) of adaptation. In contrast, a dual-learning paradigm incorporating two motor tasks, as studied here, can allow for concurrent adaptation of movement components without interference under the right conditions (Krakauer et al. 1999; Summa et al. 2012). As opposed to the cognitive tasks used in traditional dual-task studies (e.g., simple arithmetic, auditory attention tasks), motor learning tasks often have strong implicit components requiring less overt attention (Mazzoni and Krakauer 2006). This may decrease the possibility of distraction or interference from combining motor learning tasks. That being said, previous dual-learning studies have investigated the specific conditions required for concurrent learning of separate motor tasks. Krakauer et al. (1999) found that adaptation to an inertial load did not interfere with that of a visuomotor rotation, concluding that adaptation of limb kinematics and dynamics can occur independently. Tong et al. (2002) and Bays et al. (2005) elaborated on this point, arguing that two motor perturbations must depend on different kinematic parameters (e.g., hand position and acceleration, as opposed to two perturbations affecting hand path) to avoid interference. Importantly, this previous work focused on short, planar reaching movements. Given the relative complexity of walking compared with reaching, we were unsure how these findings would generalize to the context of walking.

We think that the ability of participants in the present study to adapt separate features of the walking pattern independently was also enabled by the distinct kinematic parameters and cognitive demands of each adaptation task. First, each task depended on separate movement parameters: split-belt walking primarily influences spatiotemporal, interlimb characteristics of the stepping pattern (e.g., step length symmetry), whereas joint-angle feedback altered intralimb joint kinematics. Next, they provided different sources of perturbation: a mechanical perturbation from the split-belt treadmill and a visuomotor perturbation from biased joint-angle feedback. Finally, we think that a goal of split-belt adaptation is to reduce the energetic cost associated with asymmetric walking (Finley et al. 2013). On the other hand, the objective of the joint-angle adaptation task was minimizing a visual feedback error. When considering future studies of dual-learning in walking, it is likely important to maintain similar dissociations between the demands and kinematic parameters affected by each task so as to avoid conflict between the motor commands required to complete them.

It is difficult to infer which specific brain areas may allow for dual adaptation from the current experiments. However, one likely site of neural involvement is the cerebellum, as diffuse cerebellar damage impairs locomotor adaptation (Morton and Bastian 2006). That being said, the independence with which each movement component was learned may suggest that separate cerebellar circuits are involved in each adaptation task. There are indications that medial cerebellar regions play an important role in regulating the muscle activity patterns that comprise the walking pattern, whereas intermediate regions are more involved in directing the timing, amplitude, and trajectory of limb movement (Morton and Bastian 2004). The lateral cerebellum is generally less important for balance and locomotion; however, it may be involved in controlling walking in novel situations or when visual input is needed (Marple-Horvat and Criado 1999; Morton and Bastian 2004). It is plausible that this dissociation in the roles of different cerebellar regions allowed for the independence with which step length symmetry and joint flexion angles were learned. Specifically, we speculate that split-belt adaptation relies on medial/intermediate cerebellar regions, whereas intermediate/lateral regions may be more involved in joint-angle adaptation in response to visual feedback (Ilg et al. 2008). In addition, frontal-parietal circuitry has been implicated in other forms of motor adaptation of visually guided movements (Clower et al. 1996; Luaute et al. 2009). These brain regions are likely involved here as well, especially considering the involvement of visual information in our joint-angle adaptation task.

An interesting result of this study is that providing visual feedback of either hip or knee flexion angle led to adaptation of the flexion patterns of both joints. This is not entirely surprising given the known dynamic coupling of the knee and hip joints during the swing phase of walking (Piazza and Delp 1996; Yamaguchi and Zajac 1990). However, this result could be important when considering the future implications of the present study in stroke rehabilitation. Stiff-knee gait, common in chronic stroke patients, may be caused by a combination of factors (Lucareli and Greve 2008), including quadriceps spasticity (Kerrigan et al. 1991; Sutherland et al. 1990; Waters et al. 1979), lack of control of the ankle (Kerrigan et al. 1991; Riley and Kerrigan 1999), and weakness of the hip flexor (Kerrigan et al. 1991, 1998; Riley and Kerrigan 1998). Patients may have difficulty actively controlling the knee; however, a joint-angle adaptation task could prove successful at increasing activity and strength of the hip flexors, which could, in turn, positively affect knee flexion patterns. Determining whether stroke patients are able to perform such a joint-angle adaptation task during walking is an important next step to assess the potential efficacy of this type of paradigm in rehabilitation settings.

In summary, we have shown that two distinct components of the walking pattern can be adapted simultaneously and without interference. Based on previous work, we speculate that participants were able to successfully adapt both components due to the separate kinematic parameters and demands associated with each adaptation task. The current experiment combined split-belt treadmill adaptation with a novel joint-angle adaptation task; however, future studies will be aimed at determining which other characteristics of the walking pattern can be learned in parallel to produce the greatest improvement for patients with complex gait impairments.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-048741.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.A.S. and A.J.B. conception and design of research; M.A.S. and A.T. performed experiments; M.A.S. and A.T. analyzed data; M.A.S., A.T., and A.J.B. interpreted results of experiments; M.A.S. prepared figures; M.A.S. drafted manuscript; M.A.S. and A.J.B. edited and revised manuscript; M.A.S., A.T., and A.J.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Bastian AJ. Understanding sensorimotor adaptation and learning for rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol 21: 628–633, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays PM, Flanagan JR, Wolpert DM. Interference between velocity-dependent and position-dependent force-fields indicates that tasks depending on different kinematic parameters compete for motor working memory. Exp Brain Res 163: 400–405, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clower DM, Hoffman JM, Votaw JR, Faber TL, Woods RP, Alexander GE. Role of posterior parietal cortex in the recalibration of visually guided reaching. Nature 383: 618–621, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JM, Bastian AJ, Gottschall JS. Learning to be economical: the energy cost of walking tracks motor adaptation. J Physiol 591: 1081–1095, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley JM, Statton MA, Bastian AJ. A novel optic flow pattern speeds split-belt locomotor adaptation. J Neurophysiol 111: 969–976, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain SJ, Hanson AS, Tseng SC, Morton SM. A locomotor adaptation including explicit knowledge and removal of postadaptation errors induces complete 24-hour retention. J Neurophysiol 110: 916–925, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilg W, Giese MA, Gizewski ER, Schoch B, Timmann D. The influence of focal cerebellar lesions on the control and adaptation of gait. Brain J Neurol 131: 2913–2927, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Frates EP, Rogan S, Riley PO. Hip hiking and circumduction: quantitative definitions. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 79: 247–252, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Gronley J, Perry J. Stiff-legged gait in spastic paresis. A study of quadriceps and hamstrings muscle activity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 70: 294–300, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Roth SR, Riley PO. The modelling of adult spastic paretic stiff-legged gait swing period based on actual kinematic data. Gait Posture 7: 117–124, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer JW, Ghilardi MF, Ghez C. Independent learning of internal models for kinematic and dynamic control of reaching. Nat Neurosci 2: 1026–1031, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KZ, Abbud GA, Fraser SA, Demont RG. Successful adaptation of gait in healthy older adults during dual-task treadmill walking. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 19: 150–167, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luaute J, Schwartz S, Rossetti Y, Spiridon M, Rode G, Boisson D, Vuilleumier P. Dynamic changes in brain activity during prism adaptation. J Neurosci 29: 169–178, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucareli PR, Greve JM. Knee joint dysfunctions that influence gait in cerebrovascular injury. Clinics 63: 443–450, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone LA, Bastian AJ. Thinking about walking: effects of conscious correction versus distraction on locomotor adaptation. J Neurophysiol 103: 1954–1962, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone LA, Bastian AJ. Spatial and temporal asymmetries in gait predict split-belt adaptation behavior in stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 28: 230–240, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marple-Horvat DE, Criado JM. Rhythmic neuronal activity in the lateral cerebellum of the cat during visually guided stepping. J Physiol 518: 595–603, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni P, Krakauer JW. An implicit plan overrides an explicit strategy during visuomotor adaptation. J Neurosci 26: 3642–3645, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton SM, Bastian AJ. Cerebellar control of balance and locomotion. Neuroscientist 10: 247–259, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton SM, Bastian AJ. Cerebellar contributions to locomotor adaptations during splitbelt treadmill walking. J Neurosci 26: 9107–9116, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza SJ, Delp SL. The influence of muscles on knee flexion during the swing phase of gait. J Biomech 29: 723–733, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Block HJ, Bastian AJ. Interlimb coordination during locomotion: what can be adapted and stored? J Neurophysiol 94: 2403–2415, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, McLean H, Bastian AJ. Split-belt treadmill training poststroke: a case study. J Neurol Phys Ther 34: 202–207, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, McLean H, Keller J, Danks KA, Bastian AJ. Repeated split-belt treadmill training improves poststroke step length asymmetry. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 27: 460–468, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman DS, Wityk R, Silver K, Bastian AJ. Locomotor adaptation on a split-belt treadmill can improve walking symmetry post-stroke. Brain J Neurol 130: 1861–1872, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley PO, Kerrigan DC. Torque action of two-joint muscles in the swing period of stiff-legged gait: a forward dynamic model analysis. J Biomech 31: 835–840, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley PO, Kerrigan DC. Kinetics of stiff-legged gait: induced acceleration analysis. IEEE Trans Rehabil Eng 7: 420–426, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemmich RT, Stegemöller EL, Hass CJ. Lower extremity sagittal joint moment production during split-belt treadmill walking. J Biomech 45: 2817–2821, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti Y, Rode G, Pisella L, Farné A, Li L, Boisson D, Perenin MT. Prism adaptation to a rightward optical deviation rehabilitates left hemispatial neglect. Nature 395: 166–169, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Adaptive representation of dynamics during learning of a motor task. J Neurosci 14: 3208–3224, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summa S, Palmieri G, Basteris A, Sanguineti V. Concurrent adaptation to force fields and visual rotations. Proceedings of the 4th IEEE RAS/EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics, Rome June 24–27, 2012, p. 338–343. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland DH, Santi M, Abel MF. Treatment of stiff-knee gait in cerebral palsy: a comparison by gait analysis of distal rectus femoris transfer versus proximal rectus release. J Pediatr Orthop 10: 433–441, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JA, Thoroughman KA. Divided attention impairs human motor adaptation but not feedback control. J Neurophysiol 98: 317–326, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong C, Wolpert DM, Flanagan JR. Kinematics and dynamics are not represented independently in motor working memory: evidence from an interference study. J Neurosci 22: 1108–1113, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Oviedo G, Vasudevan E, Malone L, Bastian AJ. Locomotor adaptation. Prog Brain Res 191: 65–74, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YW, Diedrichsen J, Krakauer JW, Shadmehr R, Bastian AJ. Sensory prediction errors drive cerebellum-dependent adaptation of reaching. J Neurophysiol 98: 54–62, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman J, Fuchs AF. Saccadic gain modification: visual error drives motor adaptation. J Neurophysiol 80: 2405–2416, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters RL, Garland DE, Perry J, Habig T, Slabaugh P. Stiff-legged gait in hemiplegia: surgical correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 61: 927–933, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi GT, Zajac FE. Restoring unassisted natural gait to paraplegics via functional neuromuscular stimulation: a computer simulation study. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 37: 886–902, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]