Abstract

Background

The major drawbacks of standard procedures of palatoplasty have been inadequate palatal lengthening, velopharyngeal incompetence, impaired maxillary growth with mid-face retrusion and high fistula rates. The Furlow's double opposing Z-plasty is accepted as one of the better procedures for treating cleft palates.

Methods

This paper compared Furlow's procedure to Veau Kilner Wardill's procedure performed on 63 patients from July 2000 till February 2005.

Results

The results were compared in terms of the fistula rates, palatal lengthening, nasal regurgitation, velopharyngeal incompetence, improvement in speech, hearing and maxillary growth.

Conclusions

The Furlow's technique offered better results irrespective of the age, type and extent of the cleft in the palate.

Key Words: Palatal lengthening, velopharyngeal incompetence, maxillary growth, fistula rates, Furlow's palatoplasty

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate with an incidence of 1:700 [1] and cleft palate with an incidence of 1:1600-4200 live births in Asian countries [2] and 1:3200 in Tamilnadu, India [3] is a common congenital anomaly. Till 19th century cleft palate was treated mainly with obturators [4]. It was not until Veau in 1931 introduced mucoperiosteal flaps and Kilner and Wardill modified to push back flaps, that palate surgery was taken up in earnest [4]. But these techniques had high rates of palatal fistulae, velopharyngeal incompetence (VPI), maxillary retrusion and impaired maxillary growth. Furlow published his double opposing Z-plasty for palate repair which circumvented most of these complications and is now accepted as one of the better procedures for palate repairs [4, 5, 6].

This paper is a single surgeon study of the Furlow's palatoplasty compared to Veau Kilner Wardill (VKW) push- back palatoplasty.

Material and Methods

Sixty five cases of cleft palate were operated upon by the author from July 2000 to February 2005. Two cases operated by the Langenbeck's technique have not been included in the study. 33 children underwent Furlow's palatoplasty and 30 Veau Kilner Wardill (VKW) push-back palatoplasty.

Initially all patients were operated upon by the VKW technique as this technique was followed in the centres where the author worked. Furlow's palatoplasty was initially done in cases of soft palates and narrow unilateral clefts. As surgical expertise and confidence increased Furlow's technique was used for wide bilateral clefts. Exceptions are children presenting for surgery over the age of five years when a primary pharyngoplasty is also indicated. In these cases the VKW push-back palatoplasty was combined with a pharyngoplasty. In two children, aged 2½ years and 4½years, Furlow's was done to correct a poorly done VKW where the child had severe VPI. In Furlow's series the youngest child was 8 months and the oldest, 4 ½ years and in VKW the youngest was 9 months, and oldest, a 15 year girl. All were non syndromic clefts.

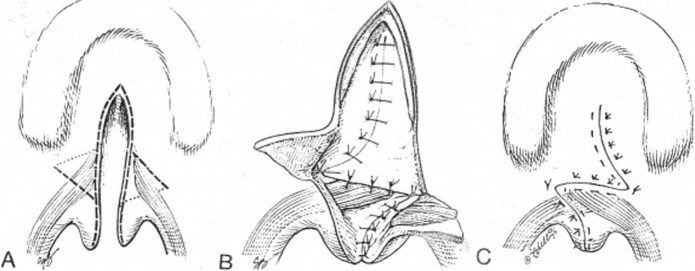

The basic principles for the Furlow's z-plasties were transposition rather than transection of the palatal muscles. The palatal muscle was elevated as part of the posterior based flap of each Z-plasty. The posterior based oral mucomuscular flap was on the left side for a right handed surgeon. The nasal Z-plasty was made as the mirror image of the oral layer. The lateral limbs of the oral Z-plasty ended over the hamuli. The posterior based flap on the left side had an angle of about 60 degrees. The lateral limb of the anteriorly based flap on the right side had an angle of almost 90 degrees. The left cleft margin was incised first and the mucoperiosteal flaps were raised without any lateral relaxing incisions. In 8 cases with wide clefts a back-cut was necessitated around the maxillary tubercle. In one 3 year old child of bilateral cleft with a very wide cleft of the hard palate, the mucoperiosteal flaps could not be approximated without tension. Here the backcut on the right side was converted into a push-back incision and the entire mucoperiosteal flap was elevated on the greater palatine vessel as an island flap. Buccal flaps were used in three cases to close the nasal layer. All flaps were sutured with 3-O Polyglactin. Horizontal mattress sutures were used to close the mucoperiosteal flaps (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

a) Double opposing Z-plasty incisions; b) Muscle included in the posterior flap; c) Final result with the recreated levator sling

All cases operated using the VKW procedure were done with the standard push back mucoperiosteal flaps islanded on the greater palatine vessels. The abnormal insertions of the palatal muscle on the posterior margins of the hard palate was completely erased, the muscles aligned and sutured together to form a levator sling. No packs were used to cover the raw mucoperiosteum. In all cases oral fluids were started the same evening after surgery.

Results

The results are as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results

| Furlow's | VKW | |

|---|---|---|

| Fistula | 3 in 33 cases, 2- | 4 in 30 cases |

| spontaneous closure, | All needed | |

| 1- secondary surgery | secondary surgery | |

| Flap necrosis | Partial necrosis in three | Nil |

| mucosal flaps. | ||

| Healed with granulation | ||

| Palatal lengthening | Excellent in all 33 | Inadequate in 9 |

| Nasal regurgitation | Nil | In 3 cases |

| of fluids and feeds | ||

| VPI | No VPI in the cases | 5 out of 30 needed |

| assessed | secondary surgery | |

| Speech | No nasal twang | Nasal twang |

| Hearing loss | No loss | In 3 with CSOM |

| Maxillary growth | 18 of 33 cases assessed, | 6 cases with |

| and malocclusion | no gross retrusion | malocclusion- |

| or malocclusion | 3 undergoing | |

| requiring orthodontic | orthodontic | |

| treatment | treatment |

Furlows palatoplasty

The longest follow up for Furlow's was 2 year and 9 months. Three children developed fistulae at the junction of the soft and hard palates giving an incidence of 9.09% which compares favourably with the 7% to 22% quoted by other authors [6, 13, 14, 15, 16]. Two fistulae closed spontaneously in about eight months. One required a secondary surgery to close the fistula, a rate of 3.03% as compared to 6-8% in other major series [13, 14]. The mucosal flap on the right side underwent partial necrosis in three cases. The raw areas healed with granulation. There was no residual fistula. Palatal lengthening was assessed per operatively by the ease with which the repaired soft palate could be manually approximated to the posterior pharyngeal wall, which was achieved in all cases. Active port closure was visually assessed by asking anaesthesiologists to make the patient light after the surgery was complete, so that the active movements of the repaired soft palate, lateral and posterior pharyngeal walls could be seen. Measurements of the elongation in the velar length was done only for the last three cases and were 14.2mm, 15.3mm and 15.2 mm respectively. None of the operated children had postoperative nasal regurgitation. Velopharyngeal incompetency (VPI) could be assessed in five of the older children who could undergo naso-endoscopy and there was no VPI as assessed by the ENT colleagues. Speech was near normal with no nasal twang. Children who underwent a secondary Furlow's procedure to correct VPI had a dramatic improvement in speech. None of the children assessed clinically had hearing loss. Maxillary growth and occlusion was checked in 18 of the 33 children and none of the children had maxillary retrusion or mal-occlusion.

With VKW repair of the 30 cases, four developed fistulas (13.33%) which required corrective surgery. This figure compares favourably with 17% to 43% for the Wardill type of repair as quoted by other authors.[4, 6, 13, 14]. There was no flap necrosis in any of the cases. Palatal lengthening was not of the same extent as in the Furlow's repair. In nine cases the soft palate could not be approximated easily with the posterior pharyngeal wall. Active port closure checked by making the child light at the end of surgery was inadequate. No measurement of the actual lengthening was done. Nasal regurgitation persisted in 3 cases even after surgery. Velopharyngeal incompetence (VPI) was assessed by nasoendoscopy. Secondary surgical procedures were needed in five cases. Speech was not clear with the children having a nasal twang. This was most noticeable in the children needing pharyngoplasty for VPI. Assessment was restricted to children below the age of 5 years at the time of surgery. Three children had impaired hearing with associated chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). Six had definite mal occlusion and maxillary retrusion and three of these children were undergoing orthodontic treatment. This did not include four children over 5 years of age at the time of primary palate surgery who were in need of orthodontic treatment.

Discussion

Cleft palate surgery till the early 20th century was replete with a large number of complications. Von Langenbeck introduced bipedicle mucoperiosteal flaps in 1859 for treating narrow clefts mainly the soft palate [4]. Modified by Wardill and Kilner in 1936, the VKW push back palatoplasty stayed the gold standard for palate surgery till the 1980's [4]. The major drawbacks of this procedure were inadequate palatal lengthening necessitating a secondary procedure to correct the velopharyngeal incompetence and improve speech, impairment in hearing, midface retrusion,impaired maxillary growth caused by extensive mucoperiosteal dissection of the hard palate and finally the high fistula rates [4, 6].

Kriens in 1970 introduced intravelar veloplasty to improve the palatal function and length [8]. He emphasised the separation of the levator muscles from the posterior palatal edge and transversely orienting the muscles.

Furlow's Palatoplasty

The major advantages of Furlow's Palatoplasty are excellent lengthening without the use of tissue from the hard palate [4, 7, 9, 18]. Complete division of the palatal aponeurosis, precise dissection of the muscles and transverse orientation of the muscles is possible [4, 5, 6, 7, 9]. The overlap of the levator achieves a better sling [9]. By avoiding a straight line incision, the zigzag incision in a rapidly moving organ like the soft palate gives better functional results [4, 5, 7]. The rate of fistulae formation is less than in other procedures[6, 13, 14, 15]. Palatal competence is better and rates of VPI were much less in all studies reported [6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. It has also been offered as a surgery for VPI [12, 20]. Large raw areas of the hard palate are not left exposed as in VKW procedures, scar formation and maxillary retrusion are minimal[6, 7, 13, 14, 19]. Speech results in all reported series are excellent [6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17] and hearing loss is an infrequent problem [6, 7, 14]. The drawbacks of this procedure include a demanding and time consuming surgery [4, 5, 6, 7]. In very wide clefts a back cut or lateral mucoperiosteal relaxing incisions may be necessary 4, 5, 6, 7] and the disadvantage of a zigzag incision is the impossibility of re-opening the soft palate other than by dividing the muscles [6, 7].

The initial results of this small series have been very good. However, a larger follow-up is necessary for a complete assessment of speech, VPI and maxillary growth.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified

References

- 1.Karoon Agrawal. Publication of the “Venture Fund” project of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 1st ed. 2001. A guide for the parents of cleft lip and palate children; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy J, Cutting CB, Michael V. Introduction to Facial Clefts. In: McCarthy J, editor. Plastic Surgery Cleft lip, palate and craniofacial anomalies. 1st ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1990. pp. 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sridhar K. Survey of 45 million rural populations for congenital defects in Tamilnadu. Procedings of 9th Congress of the International Confederation of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery; Mumbai; March 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randall P, LaRossa . Cleft Palate. In: Mc Carthy J, editor. 1st ed. Vol. 4. WB Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 1990. pp. 2723–2752. (Plastic Surgery. Cleft lip, palate and craniofacial anomalies). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furlow LT. Cleft palate repair by double opposing Z-plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:724–736. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198678060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randall P, LaRossa D, Cohen SR, Cohen MA. The double opposing Z-plasty for palate closure — Part 2. In: Jackson Ian T, Sommerlad Brian C., editors. Recent Advances in Plastic Surgery. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1992. pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furlow LT., Jr . The double opposing Z-plasty for palate closure — Part 1. In: Jackson Ian T, Sommerlad Brian C., editors. Recent Advances in Plastic Surgery. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1992. pp. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kriens OB. Fundamental anatomical findings for an intravelar veloplasty. Cleft Palate J. 1970;7:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang MH, Riski JE, Cohen SR, Simms CA, Burstein FD. An anatomic evaluation of the Furlow double opposing technique of cleft palate repair. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1999;28:672–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mc Williams BJ, Randall P, LaRossa D, Cohen S, Yu j Cohen M. Speech characteristics associated with the Furlow palatoplasty compared with other techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199609001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu CC, Chen PK, Chen YR. Comparison of speech results after Furlow palatoplasty and von Langenbeck palatoplasty in incomplete cleft of the secondary palate. Chung Gung Med J. 2001;24:628–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sie KC, Tampakopoulou DA, Sorom J, Gruss JS, Eblen LE. Results with Furlow palatoplasty in management of velopharyngeal insufficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:17–25. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirschner Re, Wang P, Jawad AF, Duran M, Cohen M, Solot C, Randall P, LaRossa D. Cleft palate repair by modified Furlow double -opposing Z-plasty: The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1998–2010. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Rossa, Jackson OH, Kirschner RE. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia modification of the Furlow's double opposing Z- plasty — long term speech and growth results. Clinics Plast Surg. 2004;31:243–249. doi: 10.1016/S0094-1298(03)00141-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng NX. Experience with Furlow's palatoplasty and its preliminary result. Zhonghua Zheng, Xing Shao Shang, Wai Ke, Za Zhi. 1992;8:43–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunther E, Wisser JR, Cohen MA, Brown AS. Palatoplasty: Furlow's double reversing Z-plasty versus intravelar veloplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1998;35:546–549. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1998_035_0546_pfsdrz_2.3.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vokurkova J, Mrazek T, Vyska T, Peslova M, Vesely J. Cleft repair by Furlow double- reversing Z-plasty: first speech results at the age of 6 years. Acta Chir Plast. 2000;42:23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guneren E, Uvsal OA. The quantitative evaluation of palatal elongation after Furlow palatoplasty. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho BC, Kim JY, Yang JD, Lee DG, Chung HY, Park JW. Influence of the Furlow palatoplasty for patients with submucous cleft palate on facial growth. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:547–554. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200407000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deren O, Ayhan M, Tuncel A. The correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency by Furlow palatoplasty in patients older than 3 years undergoing Veau-Wardill-Kilner palatoplasty: a prospective clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:85–87. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000169714.38796.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]