Abstract

A total of 50 patients undergoing cancer treatment at Malignant Disease Treatment Centre were included in the present study aimed at evaluating the psychological status of cancer patients. All patients filled a specially designed proforma and the following psychological questionnaires : General Health Questionnaire, Carroll Rating Scale for Depression, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, PGI General Well-being Scale and Quality of Life Scale. Analysis of the results showed that 22 (44%) of the cancer patients had psychiatric disorders and this number had reduced to 12 (24%) after therapy. The difference was statistically significant. Psychiatric treatment also resulted in a statistically significant reduction in level of depression as measured by Carroll Rating Scale for depression. Short term psychiatric treatment was found to be very useful in treating psychiatric morbidity and depression in cancer patients.

Key Words: Cancer, Depression, Psychiatric morbidity

Introduction

Throughout the history of mankind, certain diseases have gained prominence in societies and cultures at particular times. Their vicissitudes may or may not have been felt globally but in the minds of laymen they get imbued with almost mystical qualities. This may relate to the fact that the causative factors were undefined and the treatment modalities available at the time were ineffective. Failure of rational definition then invested these diseases with the property of being the result of sinful activities and their manifestations viewed as stigmata marking one who had transgressed the accepted social and religious norms. Examples, which easily come to mind, are leprosy, small pox, bubonic plague and tuberculosis. Today cancer seems to occupy such a place in spite of the fact that there are a number of other diseases that are far more lethal in effect.

Despite recent advances in securing remission and possible cure, cancer has remained a disease equated with hopelessness, pain, fear and death. Its diagnosis and treatment often produce psychological stress resulting from the actual symptoms of the disease, as well as patient's and family's perception of the disease and its stigma [1]. Major concerns are fear of death, dependency, disfiguration, disability and abandonment as well as disruption in the role functioning relationships and financial status. Therefore, patient's responses are modulated by medical, psychological and interpersonal factors [2]. Medical factors include site of disease, symptoms, predicted course and also the treatment modalities used. Psychological factors include pre-existing character style, coping ability, ego strength, developmental stage of life and the meaning and impact of cancer at that stage. Inter-personal factors include family and social support and the input of caregivers. Affectively, patients may experience reactions ranging from extreme anxiety, sadness, fear and anger to numbness and lack of reactivity. Guilt and attribution mechanisms play a major role. Cognitively, the patients may become highly focused and seek information aggressively or may become confused, paralysed, and unable to concentrate. Somatic complaints may increase and daily activity, appetite and sleep may be affected [2, 3].

Psychiatric morbidity in the medically ill is a reality but is often under diagnosed and undertreated as there is a tendency to explain away the symptoms experienced by the patient. Various studies have found incidence of psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients to be around 50%. More than half of psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients consists of adjustment disorders and psychological problems directly related to cancer [4], while upto 45% suffer from depression [5, 6]. Depression in cancer patients needs to be identified as it has major implication in the course and prognosis of illness. Data from several studies have convincingly documented that once an individual is diagnosed with cancer, psychological factors including depression may influence the patient's immune status and thus influence the course of the illness and also the overall quality of life [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. However, with the advent of modern psychopharmacology, cancer patients need not suffer in silence from various psychological problems as effective and timely psychiatric intervention can ameliorate most of their symptoms and improve their quality of life [12]. Not many studies have been done in India to study the effect of short term psychiatric intervention in cancer patients. Keeping this in view, the above study was undertaken.

Material and Methods

A total of 50 consecutive patients were approached and monitored for a period of 2 months. A specially designed proforma was filled and all patients underwent the following psychological tests:

General Health Questionnaire [13]

Carroll Rating Scale for Depression [14]

State-Trait Anxiety Scale [15]

PGI General Well Being Scale [16]

Quality of Life Scale [17]

The scales were administered individually to the patients and scored as per the test manual. Analysis of the scores of the above questionnaires revealed the psychological status of the patient and helped to identify probable psychiatric patients. These patients were provided with psychopharmacological (antidepressants and anxiolytics) and supportive psychotherapy treatment for a period of six weeks. At the end of treatment the patients were re-evaluated using the same psychological tests to assess the efficacy of the treatment. The data collected was tabulated and statistically analyzed using Chi-square test and Mann Whitney U test.

Results

A total of 50 patients with confirmed diagnosis of malignant disease were included in the study with their consent. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 33.48 (10.35) years. The age of the patients ranged from 12 years to 59 years. Demographic variables of the patients are given in Table 1. Majority of the patients were Hindu, married, servicemen, in the fourth and fifth decades, hailing from a rural background and educated between 6 to 10 class. None of the patients had a past or family history of psychiatric disorders. None of the patients gave a family history of cancer. All the patients described their interpersonal relation with their family members as cordial.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the cancer patients

| Characteristics | No of cancer patients |

|---|---|

| Age distribuition | |

| 12-19 years | 8 |

| 20-29 years | 2 |

| 30-39 years | 24 |

| 40-49 years | 14 |

| 50-59 years | 2 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 39 |

| Female | 11 |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 47 |

| Sikh | 2 |

| Muslim | 1 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 36 |

| Unmarried | 14 |

| Domicile | |

| Rural | 45 |

| Urban | 5 |

| Education | |

| 0-5 class | 6 |

| 6-10 class | 34 |

| 11 + | 10 |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 7 |

| Housewife | 9 |

| Service | 34 |

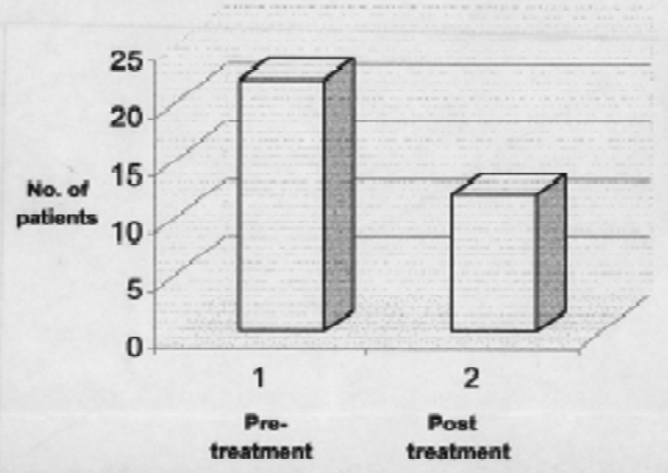

On the GHQ-12, a cut-off of >2 identified 22 (44%) patients before treatment as psychiatric cases and this number had reduced to 12 (24%) after psychiatric treatment (Fig 1). The difference was statistically significant (X2 = 4.46;df = 1; p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Psychiatric morbidity in cancer patients before and after psychiatric treatment

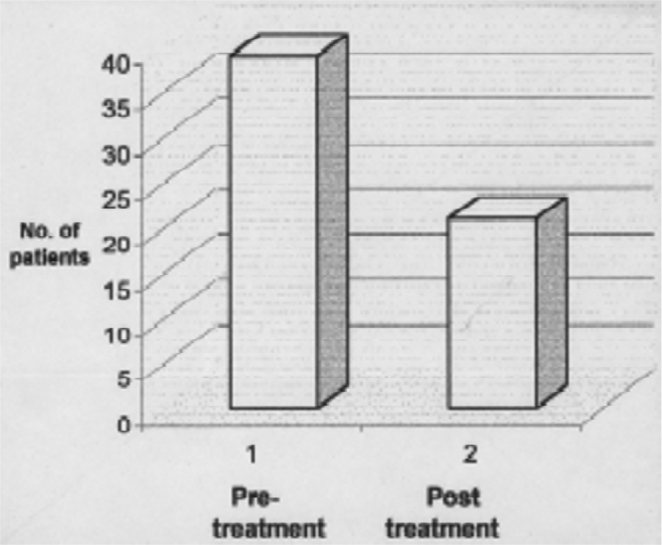

On the Carroll Rating Scale for depression a cut off score of >10 identified 39 (78%) patients as probably depressed prior to treatment. After psychiatric treatment this fell to 21 (42%) (Fig 2). The difference was statistically highly significant (x2 = 13.5; df=1;p <0.001).

Fig. 2.

Depression in cancer patients before and after psychiatric treatment

The scores obtained by the patients on the psychological tests are given in Table 2. Analysis revealed that after treatment a significant reduction in scores was noted only on the Carroll Rating Scale for depression. Though there was a marked reduction on the mean GHQ scores also, it did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Psychological test results

| Test | Pretreatment score Mean (SD) | Post treatment score Mean (SD) | Mann-Whitney test |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Health | 3.08 (2.78) | 2.0 (1.96) | NS |

| Questionnaire | |||

| Carroll Rating | 17.32 (7.75) | 11.76 (5.13) | S |

| Scale for | |||

| depression | |||

| State Trait Anxiety | 41.92 (6.91) | 39.36 (5.97) | NS |

| Inventory-S | |||

| State Trait Anxiety | 37.72 (8.4) | 35.04 (6.98) | NS |

| Inventory-T | |||

| PGI Well Being | 14.24 (4.04) | 14.44 (3.51) | NS |

| Scale | |||

| EQ-5D: | |||

| Mobility | 1.76 (0.78) | 1.48 (0.51) | NS |

| Self care | 1.44 (0.82) | 1.38 (0.58) | NS |

| Usual activities | 1.4 (0.76) | 1.28 (0.54) | NS |

| Pain | 1.84 (0.8) | 1.48 (0.71) | NS |

| Psychological functioning | 1.6 (0.65) | 1.44 (0.61) | NS |

S- Significant; NS – Not significant

Discussion

During the last few years growing dissatisfaction among patients with what they regard as dehumanized, high technology medicine, has focused the attention of medical care givers to the fact that it is not only in terms of death and disability that malignant diseases extract a severe toll, but there is evidence of substantial psychosocial morbidity [9].

In the past decades, many studies have been published on the psychological and psychiatric sequelae of a diagnosis of cancer. The disease and treatment may lead to functional restrictions or disabilities, which in turn may give rise to a diversity of psychosocial problems. These problems may also be related to a changing perspective of life. Though advances have been made recently in the treatment of malignant diseases, the psychological morbidity associated with cancer and cancer treatment has attracted less attention.

The present sample was from a military service setting and so was predominantly male. This fact may have affected the results, since male cancer patients show significantly higher depression and anxiety [12]. Similarly, the fact that 96% of the patients in the present study were less than 50 years of age may have affected the results. It has been shown that younger patients (mean age < 50 years) report significantly more depression, anxiety and general distress compared to older patients (mean age > 50 years). On the other hand, none of the patients had a past or family history of psychiatric disorders. Therefore, there was no effect of pre-existing psychiatric disorders on the results of the study.

The high level of 44% psychiatric morbidity in the present study is in agreement with some earlier studies [18] though some studies reported much lower levels of morbidity. A meta-analysis [12] revealed that the reported percentages of patients with psychological or psychiatric problems vary widely between individual studies (0%-46% for depression; 0.9%-49% for anxiety; and 5%-50% for psychological distress). Meta-analysis showed that the amount of anxiety and psychological distress in patients with cancer does not differ significantly from that in the normal population. Cancer patients showed a higher amount of depression compared with normal subjects, which supports the findings of our study. In addition, the fact that many of them improved with treatment is very encouraging. Obviously psychiatric treatment of cancer patients can certainly reduce anxiety, depression and psychological distress.

The finding of high levels of depression in cancer patients is in agreement with majority of studies in literature [12]. However, unlike many earlier studies [12], anxiety levels of the cancer patients were mostly within normal range. Here also, significant reduction in the depression scores is a very important finding and requires further study to confirm the findings. On the PGI well being scale and EQ-5D there was no significant difference in the scores. Given the short duration of the present study, this is on expected lines.

The major findings of the present study are that cancer patients show high levels of psychiatric disorders and depression. Short-term psychiatric treatment was found to be very useful in treating psychiatric morbidity and depression in cancer patients. Significant reduction in depression with short term psychiaric treatment is very encouraging and requires further detailed evaluation with a larger sample.

References

- 1.Lesko LM. Psychological issues. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 5th ed. Lippincott Raven; New York: 1997. pp. 2879–2890. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Psychiatry. 7th ed. Lippincott-Williams; New York: 2000. pp. 1850–1876. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chochinov HM, Douglas JT, Milson KG, Murray E, Lander S. Prognostic awareness and the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:500–504. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.6.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine PM, Silberfarb PM, Lipowski ZI. Mental disorders in cancer patients. Cancer. 1978;42:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3<1385::aid-cncr2820420349>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kathol RG, Mutgi A, William J, Clamon G, Noyes R. Diagnosis of major depression in cancer patients according to four sets of criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1021–1024. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Ennso M, Lander S. Prevalence of depression in the terminally ill. Effects of diagnostic criteria and symptom threshold judgements. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:537–540. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller AH. Neuroendocrine and immune system interactions in stress and depression. Psychiatric Clinic of North America. 1998;21(2):454–456. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greer S. Cancer and the mind. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:535–543. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi SK, Kumar GS, Kumar A. Psycho-oncology. In: Vyas JN, Ahuja N, editors. Textbook of Postgraduate Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Jaypee Bros; New Delhi: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derogatis LR, Morrow RG, Fetting J. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249:751–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.249.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaturvedi SK, Chandra P, Channabasavanna SM. Detection of anxiety and depression in cancer patients. NIMHANS Journal. 1994;12:141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spijker AV, Trijsberg RW, Duivenvoorden HJ. Psychological sequelae of cancer diagnosis: A meta-analytical review of 58 studies after 1980. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:280–293. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, NFR; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll BJ, Feinberg M, Smouse PE, Rawson SG, Greden JF. The Carroll Rating scale for Depression. I. Development, Reliability and Validation. Brit J Psychiatry. 1981;138:194–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.138.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speilberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists press; California: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moudgil AC, Verma SK, Kaur K, Pal M. PGI Well Being scale. Ind J Clin Psychology. 1986;13:195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrag A, Selai C, Jahanshahi M, Quinn NP. The EQ-5D- a generic quality of life measure is a useful instrument to measure quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:67–73. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omne-Pontem M, Holmberg L, Burns T. Determinants of the psychosocial outcome after operation for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1992;20A:1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90457-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]