Introduction

Desmoplastic fibroma of bone has been described as a rare, locally aggressive, benign lesion that histologically resembles a desmoid tumour of the soft tissue. It was initially described in 1958 by Jaffe, who separated it as a distinct entity from other intraosseous fibrous tumours. Since his original description, a number of small series and case reports have brought the total number of published cases to approximately 150. In a review by Crim et al, [1] the mandible accounted for 30 cases of a total of 114 cases reviewed for desmoplastic fibroma involving various bones. Mandibular involvement is reported to be approximately 40% of the various bony sites. Since Griffith and Irby [2] in 1965, first reported a case in the jaw, numerous individual cases have appeared in the literature. The histological appearance of the desmoplastic fibroma is identical to that of the extra-osseous desmoid, although the fibroma is infiltrative, there are no mitoses or nuclear atypia.

Case Report

A 9 year old girl presented with the history of swelling in left lower jaw of 2 months duration following an injury to the left angle of mandible due to a fall. The swelling was nonprogressive in size and firm in consistency, confined to the angle of the mandible on the left side. She complained of mild pain over the swelling, however she was not finding any difficulty in opening the mouth; lower jaw deviated to the right side on opening the mouth. She was able to chew semisolid soft food, speech and swallowing were normal. On examination there was a firm swelling present on the left side of the jaw with well defined margins, fixed to the mandible. Upper limit of the swelling could not be reached, skin over the swelling was normal, intra-orally lingual plate of the mandible was normal, however, the swelling could be palpated at the gingivo-buccal sulcus. Dental examination showed all normally erupted teeth. CT scan of the lesion showed irregular bony surface with hypodense lesion at the angle of mandible involving the ramus of the mandible (Fig 1). Orthopantomogram (OPG) showed normal apices of the teeth and normal inferior dental canal. FNAC was suggestive of the fibro-osseous lesion of mandible. Patient was taken up for curettage and shaving of the mandible and simultaneous biopsy of the mass. Histopathological examination revealed “desmoplastic fibroma” of mandible (Fig 2). Following surgery, cosmetically she has improved and is being followed up closely.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of the lesion showed irregular bony surface with the hypodense lesion at the angle of mandible involving the ramus of the mandible

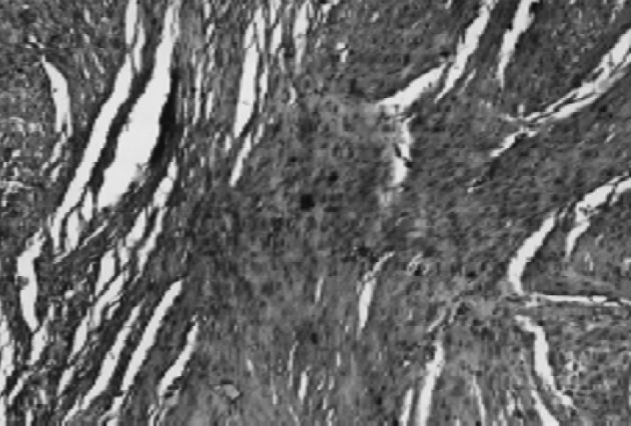

Fig. 2.

Section from tumour shows fascicles of spindle cells (mature fibroblasts) with intervening collagen

Discussion

In the head and neck desmoid fibromatosis may be intraosseous (desmoplastic fibroma) or, more often, in soft tissue, with the highest incidence in the supraclavicular region of the neck. High recurrence and persistence rates, 50% or more, accompany intralesional or marginal excision [3].

These tumours reside in a clinical grey zone between benign fibrous lesion e.g. keloids and malignant tumours. This is reflected, in part, by synonyms for desmoid fibromatosis: desmoma, aggressive fibromatosis, fibrosarcoma grade 1, desmoid type and desmoplastic fibroma of bone [4].

Desmoplastic fibroma of the jaw presents in the same manner as its counterpart in the long bones. The age incidence is usually in the first, second, or third decade. Neither sex is at greater risk. The site of predilection within the jawbone is the mandible, while the maxilla is rarely affected. The posterior mandible is most frequently involved (the ramus, angle and molar area). The premolar area and the anterior segments are less commonly affected. The initial symptoms include painful swelling of the jaw and occasionally loss of teeth. Radiographically, a well demarcated lytic lesion is seen. It is usually multilocular and often expands the bone. The radiographic differential diagnosis includes ameloblastoma, odontogenic fibroma, aneurysmal bone cyst and hemangioma. Only rarely will primary malignant lesions such as fibrosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma be suspected on the basis of radiographic evidence.

The histological features of desmoplastic fibroma and the extra-abdominal desmoid tumour are essentially identical. They are characterized by uniform-appearing fibroblastic cells in a stroma containing various amounts of collagen fibres. The morphologic differential diagnosis includes benign and malignant spindle cell tumours of bone. Fibrous dysplasia can stimulate desmoplastic fibroma in areas where fibrous tissue predominates and osteoid production is not apparent. The distinction can be made by recognising areas of bone formation by additional sampling. Also the nuclei in fibrous dysplasia are shorter and more compact-looking than the elongated, slender nuclei seen in desmoplastic fibroma. Low grade intraosseous osteosarcoma, another tumour that can mimic desmoplastic fibroma, can also be excluded by identification of bone formation. Non-ossifying fibroma and solitary congenital fibromatosis of bone can be confused with desmoplastic fibroma. Low grade fibrosarcoma poses the most difficult problem in the histologic differential diagnosis; in fact, the distinction may not always be possible and can only be detected when it recurs and metastasizes [5]. However, fibrosarcoma is more cellular, with a recognizable herringbone pattern and plumper, larger cells than those in desmoplastic fibroma. Cytologically hyperchromasia with anaplasia and mitotic activity quantitatively surpasses the rare mitotic figures occasionally seen in desmoplastic fibroma.

Jaffe, in his discussion of the treatment of desmoplastic fibroma of bone, recommended segmental resection as the treatment of choice and noted that if the lesion is curetted and recurs, segmental resection or a more thorough curettage should be performed. Wide resection or a thorough “marginal” curettage was the preferred method of treatment while local or limited curettage often led to continued growth of the tumour. It has been observed by Bertoni et al, that curettage or peripheral ostectomy achieved with a burr drill achieves better local tumour control.

There are conflicting reports regarding the role of radiotherapy in the management of desmoid tumours. In 1928, Ewing and in 1944, Pack and Ehrlich, stated that radiation therapy could effect regression of desmoid tumours, but this process was slow. Other authors, even recently, have judged radiation to be of limited value in the curative treatment of patients with desmoid tumours. Many of these opinions have been based upon experience in the orthovoltage era in the treatment of extensive lesions with low doses. In the last decade, there have been several reports documenting that complete and long term regression may be achieved using modern equipment and dose levels greater than 50 Gy. They confirm the observation of Ewing that regression is generally quite slow with radiotherapy. Radiation therapy is recommended in those situations where wide-field resection without significant morbidity is not possible for gross local disease. Kiel [6] has reported a partial or complete response in 76% of patients, and 59% were disease free at 9-94 months follow up. Role of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy in the management of desmoid tumours is not clear.

Desmoplastic fibroma is a rare, well-differentiated fibrous tumour with a slow but aggressive potential for growth. This lesion, while incapable of metastasizing, may recur locally when incompletely excised and thorough curettage with possible widening of margin with a bur (peripheral ostectomy) is the treatment of choice in early lesions, lesion growing outside the reactive bony rim requires wide excision.

References

- 1.Crim JR, Gold RH, Mirra JM, Eckardt JJ, Bassett LW. Desmoplastic fibroma of bone: radiographic analysis. Radiology. 1989;172:827–832. doi: 10.1148/radiology.172.3.2772196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith JG, Irby WB. Desmoplastic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsakis JG, Raslan W. Pathological consideration, extra-abdominal desmoid fibromatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:331–334. doi: 10.1177/000348949410300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayal AG, Ro JY, Goepfert H, Cangir A, Khorsand J, Flake G. Desmoid fibromatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 25 children. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1986;3:138–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inwards CY, Unni KK, Be about JW, Sim FH. Desmoplastic fibroma of bone. Cancer. 1991;68:1978–1983. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911101)68:9<1978::aid-cncr2820680922>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiel KD, Suit HD. Radiation therapy in the treatment of aggressive fibromatosis (Desmoid tumours) Cancer. 1984;54:2051–2055. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841115)54:10<2051::aid-cncr2820541002>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]