Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have shown great promise in the treatment of hematologic malignancies but more variable results in the treatment of solid tumors and the persistence and expansion of CAR T cells within patients has been identified as a key correlate of antitumor efficacy. Lack of immunological “space”, functional exhaustion, and deletion have all been proposed as mechanisms that hamper CAR T-cell persistence. Here we describe the events following activation of third-generation CAR T cells specific for GD2. CAR T cells had highly potent immediate effector functions without evidence of functional exhaustion in vitro, although reduced cytokine production reversible by PD-1 blockade was observed after longer-term culture. Significant activation-induced cell death (AICD) of CAR T cells was observed after repeated antigen stimulation, and PD-1 blockade enhanced both CAR T-cell survival and promoted killing of PD-L1+ tumor cell lines. Finally, we assessed CAR T-cell persistence in patients enrolled in the CARPETS phase 1 clinical trial of GD2-specific CAR T cells in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Together, these data suggest that deletion also occurs in vivo and that PD-1-targeted combination therapy approaches may be useful to augment CAR T-cell efficacy and persistence in patients.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells are a promising new technology in the field of cancer immunotherapy. Early clinical data in patients with hematologic malignancies has been encouraging,1,2 however CAR T-cell treatment of patients with solid tumors has had limited success.3,4,5 More work is needed to optimize CAR T-cell therapy in general, and how best to ensure the antitumor efficacy of CAR T cells in solid tumor patients is less clear. For B-cell malignancies, a systematic review has identified preconditioning chemotherapy and CD19-specific CAR T-cell persistence as positively influencing progression-free survival.6 In neuroblastoma patients receiving first-generation GD2-specific CAR T cells, better clinical outcomes were observed in those patients with CAR T cells detectable in blood beyond 6 weeks.4,7 These findings indicate that CAR T-cell persistence is essential for positive patient outcomes.

Lack of CAR T-cell persistence has been attributed to several factors. In early clinical trials of CAIX-, CD19-, or CD20-specific CAR T cells, limited persistence postinfusion was observed, and suggested that immune-mediated deletion may have occurred.5,8,9 Other groups have identified activation-induced cell death (AICD) resulting from IgG CH2CH3 region-derived spacer elements of the CAR binding the Fc-receptor on innate immune cells as a factor in lack of CAR T-cell persistence in preclinical models.10,11,12 AICD of tumor-specific T cells may also occur in the absence of Fc-receptor-engaging chimeric antigen receptors when T cells encounter cognate antigens.13,14 Although these processes are central to T-cell homeostasis, they may also limit CAR T-cell therapies that induce potent T-cell activation via multiple intracellular signaling domains.15,16,17

Suppression or exhaustion of T cells can also contribute to failure of CAR T-cell expansion and persistence, and may partly be mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 interactions, which attenuate T-cell responses after antigen18,19,20 encounter.18,19,20 Preclinical studies in a Her2+ mouse tumor model have indicated that PD-1 is upregulated on CAR T cells in vivo and can contribute to a lack of efficacy.21 In one recent paper, exhaustion resulting from tonic CAR signaling was identified in GD2-specific CAR T cells, although this may be specific to both the single chain variable fragment (scFv) in question (14g2a) and the intracellular signaling domains of the CAR, with CD28 promoting, and 41BB reducing, CAR T-cell exhaustion.22

Thus, the relative importance of factors that can limit CAR T-cell persistence remains unclear. Among these factors, functional exhaustion and AICD have been identified in preclinical in vitro and in vivo models, and CAR-specific immune responses not performing prior lymphodeletion have been found to reduce CAR T-cell persistence in patients. Hence, we considered it important to fully define the effects of our third-generation CAR encoding CD3ζ, CD28, and OX40 on T-cell activation, viability, and function in vitro in order to identify factors that may influence CAR T-cell persistence in patients. Importantly, our vector incorporates both the 14g2a scFv and the problematic IgG CH2CH3 spacer identified by others as discussed above. Accordingly, we used samples obtained in preparation of and during the conduct of the CARPETS trial, a phase 1 clinical trial of third-generation GD2-specific, iCasp9-expressing, autologous peripheral blood CAR T cells (GD2-iCAR-PBT) in patients with metastatic melanoma, to better understand the events that occur during GD2-iCAR PBT activation.

Here, we show that GD2-iCAR T cells undergo rapid activation after antigen stimulation; demonstrate potent effector functions and only transient expression of markers of T-cell exhaustion. While we did not observe CAR tonic signaling leading to significant functional exhaustion, we did find clear evidence of reduced cytokine secretion and AICD after repeated stimulation. In this report, we also aimed to identify practical ways of improving the effectiveness of CAR T cells and so we tested the recently approved melanoma therapeutic, pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (mAb), for its ability to promote CAR T-cell survival and function. Importantly, PD-1 blockade was able to preserve cytokine secretion and prevent CAR T-cell AICD in vitro. We have also monitored CAR T-cell persistence and immune phenotype in four CARPETS trial patients. The data presented here offer a strong scientific rationale for an anti-PD-1/CART-cell combination therapy approach in clinical trials of GD2-specific CAR T-cell therapy.

Results

GD2-specific CAR T cells do not constitutively express PD-1 or LAG-3 and are not functionally exhausted

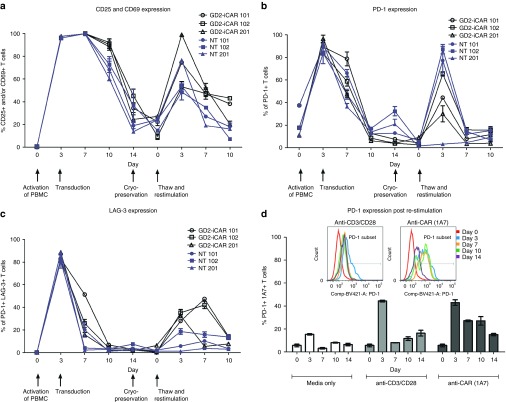

To understand what occurs to the GD2-iCAR T cells when they encounter antigen, we first analyzed markers of activation and exhaustion after stimulation in vitro. We tracked these markers during each step of the GD2-iCAR T-cell manufacturing process: initial activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), retroviral transduction of the activated T cells with the vector SFG.iCasp9.2A.14g2a.CD28.OX40.ζ, subsequent expansion of the CAR T-cell product in IL-7 and IL-15.23 We also assessed marker expression after cryopreservation, and upon restimulation of the thawed CAR T-cell product (Figure 1). GD2-iCAR T cells manufactured by this process had a predominately effector or effector memory phenotype, with smaller proportions of naive or central memory T cells.23 Further experiments described in this paper use patient-matched PBMC and nontransduced T cells (NT T cells) as controls. NT controls were subject to the same expansion conditions as CAR T cells and have a similar effector memory phenotype, whereas PBMC have been gradient-purified but are otherwise unmanipulated. We observed high levels of CD25, CD69, PD-1, and LAG3 expression during the initial activation, but only low levels of these markers on resting CAR T cells. CD25, CD69, PD-1, and LAG3 were upregulated again following restimulation of CAR T cells after cryopreservation, but to a lesser extent. Interestingly, direct restimulation of the CAR T cells via the CAR with the 1A7 anti-idiotypic antibody produced higher and more sustained levels of PD-1 expression on the cultured T cells for Patients 101 and 102, compared to stimulation via CD3 and CD28 endogenous receptors (Figure 1d). This suggests that a more exhausted or less functional phenotype is induced by CAR signaling and although CAR T cells are not exhausted upon administration, they may become so after antigen encounter in vivo. Minimal TIM-3 expression was detected on CAR T cells during expansion or restimulation (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Markers of activation and exhaustion on GD2-iCAR and paired nontransduced T cells in vitro. Patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells were activated, transduced with GD2-iCAR retroviral vector and expanded for 14 days before cryopreservation. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and nontransduced (NT) T-cell controls were manufactured from four patients with metastatic melanoma. Cells were then thawed and restimulated. (a) CD25 and CD69 expression during culture. (b) PD-1 expression during culture. (c) LAG-3 expression during culture. (d) Difference in PD-1 expression after restimulation with 1A7 or -anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. Representative data are shown for patient 101. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, with graphs displaying mean ± standard error of the mean. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

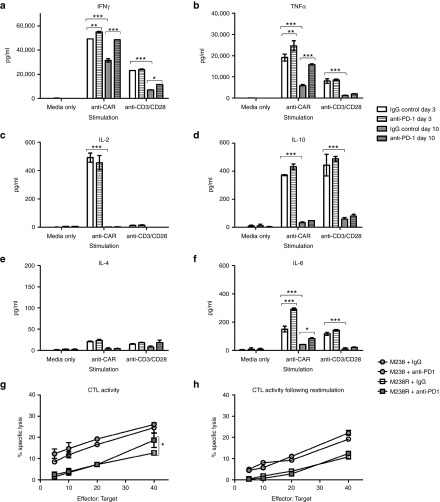

The use of the term “exhausted” to describe T cells expressing markers such as PD-1 remains controversial and may instead represent T cells undergoing chronic antigen stimulation.24,25 A better measure of whether T cells are truly exhausted is their functional capacity after stimulation.18 CAR T cells demonstrate potent effector functions including cytokine secretion, particularly of IFNγ and TNFα, cytotoxic activity and proliferative functions following a 3-day stimulation (Figure 2, see Supplementary Figure S2) and thus show no evidence of functional exhaustion. Others have reported decreased function of CAR T cells following longer-term cultures and so we rested CAR T cells for 4 days and then stimulated for a further 3 days with anti-CAR or anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies. On day 10, there were significantly reduced levels of IFNγ and TNFα, IL-6 and IL-10 production, and a complete loss of IL-2 production. Inclusion of pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 mAb) in the repeated stimulation cultures was able to restore IFNγ and TNFα production, although IL-2 production was not rescued (Figure 2a–f). Reduced cytokine production following repeated stimulation was also observed for NT control T cells, and thus was not an intrinsic function of CAR signaling but rather a global effect resulting from long-term culture of T cells (see Supplementary Figure S2a). Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte (CTL) activity, on the other hand, was not significantly reduced after culture and restimulation, and the inclusion of anti-PD-1 mAb provided only modest enhancement (Figure 2g,h). Likewise, proliferation was not enhanced by PD-1 blockade (Supplementary Figure S2b,c). Thus GD2-iCAR T cells are not functionally exhausted, and do not become so after long-term culture and repeated stimulation. However, they do lose some of their functional capacity for multiple cytokine secretion suggestive of a more terminally differentiated phenotype, and PD-1 blockade partially restores this function.

Figure 2.

Functional capacity of GD2-iCAR T cells in vitro with or without PD-1 blockade. Thawed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells were stimulated via CD3/CD28 or CAR in the absence of exogenous cytokine and in the absence (white) or presence (gray) of 20 µg/ml anti-PD-1 blocking antibody. Supernatants were collected after 3 days (day 3 plain bars) stimulation or 3 days after a restimulation on day 7 (Day 10, striped bars) and diluted 1/10 prior to analysis for cytokine secretion. (a) IFNγ. (b) TNFα. (c) IL-2. (d) IL-10. (e) IL-4. (f) IL-6. (g) CAR T-cell killing of GD2+ PD-L1- (M238, circles) and PD-L1 + (M238R, squares) melanoma cell lines ± 20 µg/ml anti-PD-1. Cells were thawed, rested overnight and then cultured with 51Cr-labeled tumor lines for 6 hours. (h) CAR T-cell killing of melanoma cell lines on day 7 after 3 days of stimulation. Cells were thawed, rested overnight and then stimulated with anti-CAR for 3 days and rested for 4 days before culture with 51Cr-labeled tumor lines for 6 hours. Flow samples were analyzed in duplicate and 51Cr assays in triplicate. Representative data are shown for patient 101, and graph display mean ± standard error of the mean. Cytokine secretion for nontransduced controls are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Observations of long-term (>7 days) culture also revealed that GD2-iCAR T-cell proliferation required either exogenous cytokine or stimulation of CD3/CD28 or CAR and was not constitutive, as has been reported for other CAR constructs.26 Following CAR-specific stimulation, the proportion of viable CAR-expressing cells decreased, the proportion of nonviable CAR-expressing cells increased and the remaining viable population had lower levels of CAR expression as measured by 1A7-PE MFI (see Supplementary Figure S2d,e).

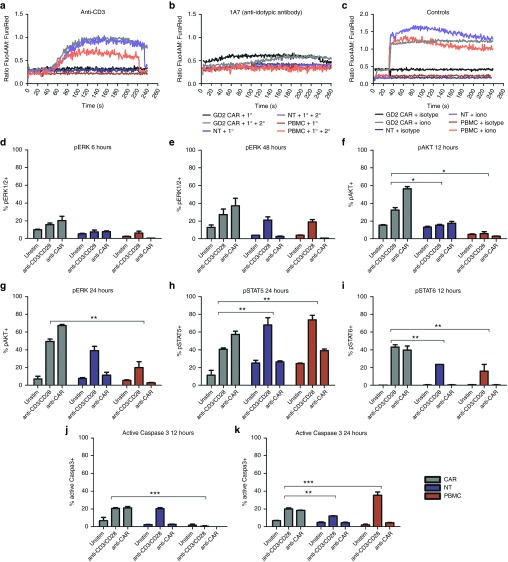

GD2-specific CAR T cells have basal levels of activation, and CAR engagement results in a rapid induction of downstream signaling events

To better understand the events following GD2-iCAR T-cell activation, we compared CAR T cells stimulated either by their CAR or CD3/CD28 molecules with NT controls and normal PBMC from the same patient (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3). As reported previously,27 we observed distinct differences in the levels and timing of calcium flux, with flux occurring immediately after CAR engagement without the requirement for cross linking (Figure 3a–c). We also found that CAR stimulation resulted in more rapid ERK phosphorylation, which was detectable at levels above unstimulated background by 6 hours in stimulated CAR T cells compared to 48 hours for stimulated NT controls or PBMC (Figure 3d,e). Stimulated CAR T cells were also more highly pERK+ when compared to stimulated controls. Likewise, AKT was also more rapidly phosphorylated in CAR T cells and pAKT was detectable at higher frequency in stimulated CAR T cells compared to controls (Figure 3f,g). There were also higher basal levels of phosphorylation for these two signaling molecules in unstimulated CAR cells, which suggests some level of basal activation as identified by others.22 Conversely, peaks in phosphorylated Stat5 and 6 appeared at the same time after stimulation for CAR, NT controls, and PBMC although a greater percentage of CAR T cells were pStat6+ and a lower percentage were pStat5+, compared to controls (Figure 3h,i). Finally, the active form of caspase 3 was detected at 12 hours poststimulation for CAR T cells and NT controls, compared to 24 hours for PBMC (Figure 3j,k). Thus, the CD28, OX40 and CD3ζ domains of the third-generation CAR result in rapid activation and calcium flux of GD2-iCAR T cells without receptor cross-linking, and GD2-iCAR T cells have higher basal levels of activation that may make them more susceptible to AICD in vivo. Importantly, NT T-cell controls also displayed higher basal levels of pAKT than PBMC controls, as well as a more rapid activation of caspase 3 poststimulation, which suggests that the activated phenotype is also due to the expansion culture conditions and not solely to CAR signaling. As previously noted, the culture conditions generate a majority of effector/effector memory T cells.23

Figure 3.

Comparison of downstream signaling events following chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) or CD3/CD28 stimulation. Calcium flux after stimulation of thawed CAR T cells with primary (1°) antibodies specific for (a) the CAR (1A7) or (b) the CD3 (OKT3) receptors, with or without cross-linking by antimouse IgG secondary (2°) antibodies. (c) Ionomycin and isotype control and a secondary antibody were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Anti-CD28 and anti-OX40 antibodies were also used in conjunction with anti-CD3 but did not induce markedly different calcium flux compared to anti-CD3 alone (data not shown). CAR T cells, nontransduced (NT) T cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were stimulated via CAR or CD3/CD28 receptors and analyzed for signaling molecule phosphorylation. (d) and (e) pERK+ T cells at 6 and 48 hours. (f) and (g) pAKT+ T cells 12 and 24 hours. (h) pSTAT5+ T cells at 24 hours. (i) pSTAT6+ T cells at 12 hours. (j) and (k) active caspase 3 in T cells at 12 and 24 hours. CAR T cells and NT T cells and PBMC were tested in duplicate. Representative data are shown for patient 102, and graphs display mean ± standard error of the mean. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

GD2-specific CAR T cells undergo AICD after repeated antigen stimulation

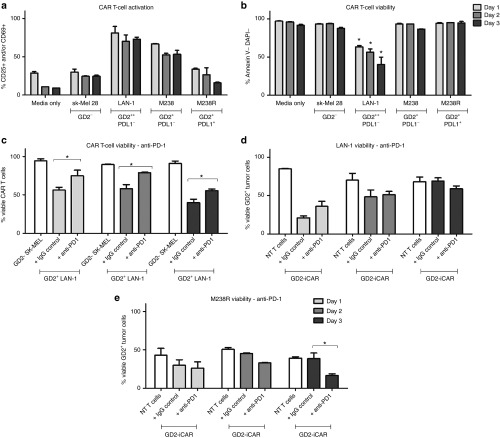

Given that CAR engagement with an anti-idiotypic antibody-induced marker of AICD, we wished to further explore the events following antigen encounter by CAR T cells, however it is difficult to model complex tumor environments in vitro. Prolonged or repeative antigen “stress-test” models of repeated stimulation have been reported by others,22,28 and give results that better correlate with in vivo data. We performed this “stress-test” assay with GD2-iCAR T cells from patients that were repeatedly passaged onto GD2+ melanoma (M238 or M238R) or GD2+ neuroblastoma (LAN-1) cells every 24 hours (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure S4). At each transfer, the survival of the tumor cells was analyzed by Annexin V and DAPI (4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride) staining, and a sample of the CAR T-cell population was also retained for analysis of viability and activation markers (CD25 and CD69).

Figure 4.

Activation-induced cell death (AICD) after repeated antigen stimulation of GD2-iCAR T cells with GD2+ tumor cells. Thawed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells were passaged daily onto tumor cells, and cells were collected at days 1, 2, and 3 for analysis of activation (CD25 and CD69) and cell death (Annexin V and DAPI) by flow cytometry. SK-Mel cells provide a GD2- control and nontransduced (NT) T cells provided controls lacking CAR expression. Anti-PD-1was included in some cultures. CAR T-cell activation (a) and viability (b) after repeated stimulation with tumor cell lines. (c) CAR T-cell death after repeated stimulation by GD2hi neuroblastoma cell lines (LAN-1), with or without anti-PD-1. (d) CAR T-cell killing of GD2hi PD-L1- neuroblastoma cells (LAN-1), with or without anti-PD-1. (e) CART-cell killing of GD2+PD-L1+ melanoma cells (M238R), with or without anti-PD-1. Repetitive antigen stress-test assays were performed in duplicate. Representative data are shown for patient 101, and graphs display mean ± standard error of the mean. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure S4.

Using this assay, we found that the percentage of viable GD2-iCAR T cells decreased with each stimulation and this depended on the level of antigen expression because melanoma cell lines with lower GD2 expression (M238) induced lower levels of CAR T-cell death compared to the highly GD2+ LAN-1 cell line (Figure 4a,b). In order to identify potentially beneficial combination therapies, we then included the currently available antimelanoma therapy, pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 mAb), in these cocultures to see whether it affected AICD. Anti-PD-1 mAb did not affect activation levels but was able to completely restore CAR T-cell viability to levels observed for CAR T cells cultured with GD2- cell lines on days 1 and 2, although by day 3 this effect lessened (Figure 4c and Supplementary Figure S4c). PD-1 blockade also resulted in enhanced killing of the PD-L1+ melanoma cell line (M238R, Figure 4e), but not of the PD-L1- cell lines (LAN-1: Figure 4d, M238: Supplementary Figure S4d).

The third-generation CAR incorporates an inducible caspase 9 suicide gene (iCasp9) and it is possible that this could contribute to the AICD observed. To investigate this possibility, we generated CAR T cells from the same patient PBMC using an earlier generation vector that encodes CD3ζ, CD28, and OX40 signaling domains but not iCasp9. These cells were found to be equally susceptible to AICD cell death when repeatedly stimulated with GD2+ LAN-1 cells, 1A7 anti-idiotypic antibody or via CD3/CD28 (Supplementary Figure S4e).

AICD is PD-1 dependent and can occur in the absence of tumor-derived PD-L1

In stimulation assays using plate-bound anti-CD3/CD28 or 1A7 antibodies, PD-1 blockade enhanced cytokine production (Figure 2), and in stress-test assays, PD-1 blockade promoted the survival of CAR T cells after activation with the PD-L1- cell line LAN-1 (Figure 4). This result suggested that homo- or hetero-typic interactions between PD-1-expressing T cells and T cells expressing PD-1 ligands such as PD-L1 might contribute to the observed AICD and suppression of T-cell function. Although PD-L1 expression on intratumoral lymphocytes has been recently reported,20 we have not found previous reports of PD-L1 expression on CAR T cells.

After stimulating the CAR T-cell product in vitro, we found that PD-L1 expression peaked at days 3–7 poststimulation (Figure 5a). Given that PD-L1+ T cells have been little characterized in the literature, we analyzed the PD-L1+ CAR T cells for surface markers and function. We found that they had equivalent levels of activation marker expression and higher levels of PD-L2 and FASL expression but demonstrated lower levels of proliferation and lower PD-1 and LAG-3 expression than PD-L1- CAR T cells (Figure 5b). A transient PD-L1 and PD-1 double-positive population was observed on day 3 after stimulation, which accounted for 40% of the total GD2-iCAR PBT population. Freshly isolated PBMC expressed PD-L1 primarily on non-CD3+ cells, including CD14+ macrophages, and PD-L1 was not coexpressed with PD-1. However, when PBMC were activated with anti-CD3/CD28, ~40% of T cells were likewise found to coexpress PD-1 and PD-L1. We also noted that although PD-1 was more highly expressed on the CD4+ subset before and after activation, its ligand, PD-L1, was expressed at equivalent levels before activation and more highly on the CD8+ subset after activation (Supplementary Figure S5a,b,d). Blockade of PD-L1 with a specific mAb inhibited AICD significantly on day 1 of coculture, but not on day 2 or day 3, and enhanced killing of the PD-L1+ M238R cell line, but not of the PD-L1- M238 and LAN-1 cell lines (Figure 5e–h). Blockade of PD-L2 had no significant effect on CAR T-cell viability. We also performed knockdown of either PD-1 or PD-L1 by siRNA, but only achieved a transient reductions in surface expression of 30–40%, however, there was a trend toward increased viability of CAR T-cells after PD-1 knockdown whereas PD-L1 knockdown significantly reduced CAR T-cell survival (data not shown). We hypothesize that these different effects relate to differences in PD-L1 forward and reverse signaling upon binding to PD-1,29,30 with reverse signaling in PD-L1+ CD8 T cells reportedly promoting survival.

Figure 5.

PD-1/PD-L1-dependent activation-induced cell death (AICD) after activation of GD2-iCAR T cells. (a) PD-L1 expression on thawed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells after stimulation in vitro. (b) Immune phenotype of CAR PD-L1+ and PD-L1- T cells at day 3 poststimulation. Immune phenotype defined as: Naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), effector memory (Tem; ––CD45RA–CCR7–), central memory (Tcm; –CD45RA–CCR7+), effector –(CD45RA+CCR7–), activated (CD25+/CD69+), proliferating (CFSE low). (c) CAR T-cell viability after repetitive stimulation with LAN-1. (d) GD2+PD-L1- M238 tumor cell viability and (e) GD2++PD-L1- LAN-1 tumor cell viability and (f) GD2+PD-L1+ M238R tumor cell viability after stress-test assay with PD-L1 blockade (anti-PD-L1). Repetitive antigen stress-test assays and flow cytometry analyses were performed in duplicate. Representative data are shown for patient 101, and graphs display mean ± stanadard error of the mean. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

Others have reported Fas Cell Surface Death Receptor and Ligand (FAS-FASL) interactions are critical for AICD of CAR T cells.10,15 We found that CAR T cells have constitutively high FAS expression, and upregulate intermediate levels of FASL after activation (see Supplementary Figure S5c). Blockade of FAS also resulted in reduced AICD as expected (see Supplementary Figure S5e). However, in some cases, when FAS-blocking antibody was added to the tumor cell coculture stress-test assay, tumor cells maintained higher viability (see Supplementary Figure S5f–h). Thus, blockade of FAS or PD-1 interactions between CAR T cells can promote their survival, but only PD-1 blockade was found to consistently preserve CAR T-cell cytotoxic function.

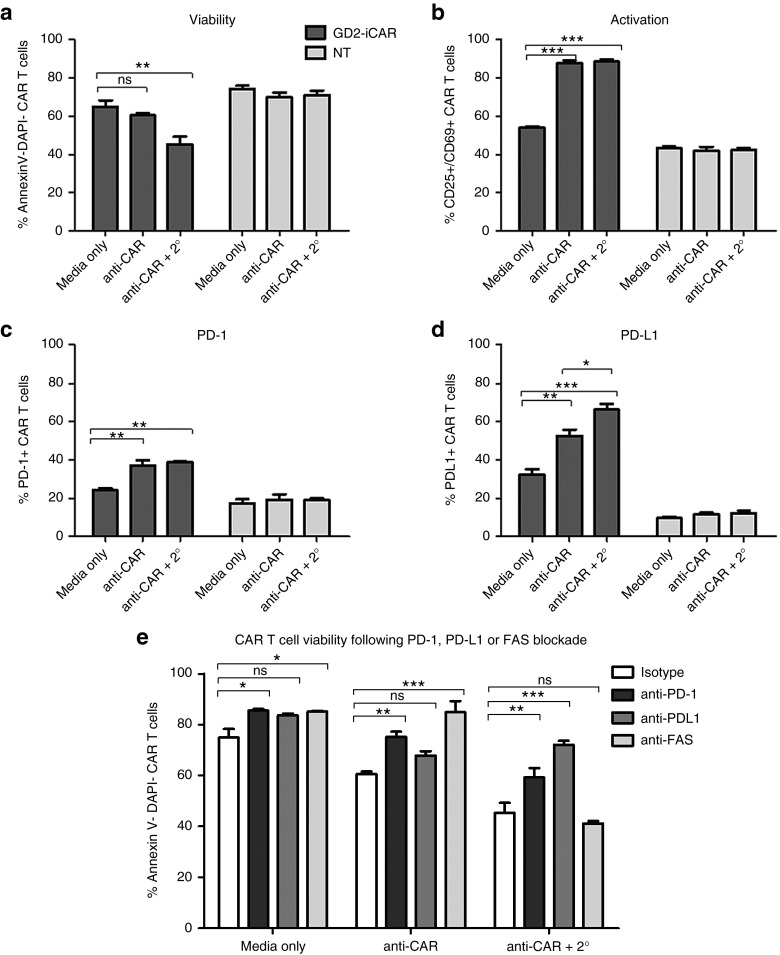

To isolate extrinsic signals provided by tumor cells during coculture from CAR T-cell-intrinsic signaling occurring after activation, we simulated repeated antigen engagement by cross-linking CAR-bound 1A7 antibody with a secondary antimouse IgG antibody (Figure 6). This result confirmed that direct CAR engagement could induce AICD in the absence of tumor cells because the percentage of cells undergoing AICD significantly increased when the 1A7 antibody was cross-linked by a secondary antibody (Figure 6a,b). PD-L1 expression, but not PD-1 expression, was also significantly increased by cross-linking (Figure 6c,d). We found that blocking antibodies to both PD-1 and PD-L1 prevented AICD after cross-linking (Figure 6e), in agreement with the findings from the tumor coculture stress-test assays. In particular, anti-PD-L1 restored CAR T-cell viability to the level of unstimulated cells.

Figure 6.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cross-linking also induces activation-induced cell death. (a) Viability, (b) activation, (c) PD-1, and (d) PD-L1 expression after CAR cross-linking with 1A7 and secondary antibody (2°) of thawed CAR T cells and nontransduced (NT) controls. (e) GD2-iCAR T-cell AICD in the presence of PD-1-, PD-L1-, or FAS-blocking antibodies after CAR cross-linking. Cross-linking assays and flow cytometry analyses were performed in duplicate. Representative data are shown for patient 101, and graphs display mean ± stanadard error of the mean. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

GD2-specific CAR T cells demonstrate limited persistence in patients and upregulate PD-1 and PD-L1 after infusion

We have examined patient-derived CAR T cells stimulated in vitro but although these experiments have identified some important potential factors in CAR T-cell persistence and efficacy but we cannot fully recapitulate the complex environment that influences CAR T-cell persistence within patients. In the CARPETS study, we have the opportunity to observe the fate of CAR T cells administered to the first four patients enrolled in this trial. The first cohort of patients, 101 and 102, received single IV injections at dose level 1 of 1 × 107 CAR T cells/m2 in conjunction with dabrafenib therapy but with no prior lymphodepletion. After a protocol amendment, the second cohort of patients, 201 and 203, received single IV injections at dose level 2 of 2 × 107 CAR T cells/m2. Patient 201 received lymphodepleting fludarabine and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy before the CAR T-cell infusion. Patient 203 received the CAR T-cell dose with dabrafenib and trametinib without prior lymphodepletion.

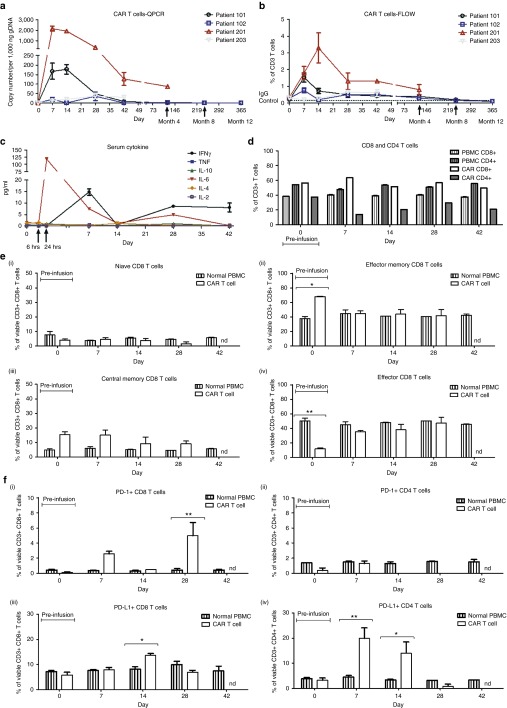

We observed limited expansion or persistence of the CAR T cells in Patients 101, 102, and 203. Quantitative PCR measurements of the CAR transgene in peripheral blood indicate that CAR T-cell numbers peaked around day 7, declined after day 14, and were undetectable by day 42 for Patients 101 and 102 although Patient 203 had very low levels of circulating CAR T cells at all time points from day 7 to day 42 (Figure 7b) . Fluorocytometric detection of peripheral blood CAR T cells followed a similar time-course, and serum cytokines also peaked at around day 7 postinfusion with a transient increase in IL-6 observed for all patients and an increase in IFNγ observed for Patient 102 (Figure 7a,c and Supplementary Figure S6b,c). The lympho-depleted Patient 201 showed more marked expansion of CAR T cells after infusion with a 10–100-fold increase in transgene copy number detected at days 7 and 14, compared to Patients 101 and 102, and a later peak in IL-6 around day 28. However, CAR T-cell numbers in the peripheral blood still declined from day 14 to day 42 and were only detectable at low levels by month 4. This suggests that fludarabine and cyclophosphamide conditioning improved expansion but did not dramatically improve persistence of GD2-iCAR-PBT cells in vivo. However, given that only one patient has received preconditioning in this study so far, we cannot draw definitive conclusions.

Figure 7.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell persistence and immune phenotype in patients receiving third-generation GD2-specific CAR T cells for the treatment of V600 BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. (a) Flow cytometry using 1A7 to detect GD2-iCAR-expressing T cells in peripheral blood. (b) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) to detect GD2-iCAR transgene-positive cells in peripheral blood. (c) Patient 102 serum cytokine levels. (d) Patient 102 CD4 and CD8 CAR T-cell subsets for peripheral blood mononuclear cells, the GD2-iCAR T-cell product and circulating GD2-iCAR T cells detected from day 7 postadministration. (e) Patient 102 CD8+ T-cell immune phenotype and (f) PD1/PD-L1 expression on peripheral blood normal T cells and 1A7+ GD2-iCAR T cells. Experiments were performed in duplicate (flow cytometry) or triplicate (QPCR), with graphs displaying mean ± standard error of the mean. Gating strategy and data for Patients 101, 201 and 203 are shown in Supplementary Figure S6.

Compared to PBMC drawn at the same time from the same patient, peripheral blood CAR T cells had an inverted CD4:CD8 ratio (Figure 7d), with CD8 T-cell frequency increased for all patients except Patient 201 (see Supplementary Figure S1b). Compared to the infused CAR T-cell product, which had a predominately effector-memory phenotype, the majority of peripheral blood CAR T cells had either an effector-memory or effector phenotype and also had upregulated expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 (Figure 7e,f and Supplementary Figure S6d,e). Circulating CD8+ CAR T cells had significantly higher PD-1 surface expression compared to normal peripheral CD8+ T cells for both Patients 101 and 102, whereas for Patient 201 CD4+ CAR T cells had significantly higher PD-1 expression than normal peripheral CD4+ T cells. In the case of PD-L1, Patient 102 had significantly higher surface expression on both CD4+ and CD8+ CAR T cells compared to normal T cells at multiple time points following infusion. Significantly higher PD-L1 surface expression was also observed on CD4+ CAR T cells from Patient 101 and on CD8+ CAR T cells from Patient 203.

Lack of persistence may be related to activation induced cell death, as we observed in vitro, or may be due to a CAR-specific immune response mounted after infusion. To investigate this possibility, we assayed patient sera for human anti-mouse antibody IgG (HAMA) and patient PBMC for CAR-specific CTL response. No HAMA was detected at any time point postinfusion in Patients 101 and 102, whereas Patient 201 had pre-existing HAMA that increased approximately fivefold by month 4 following CAR T-cell infusion (see Supplementary Figure S7a). Patient 203 had very low HAMA levels that did not increase over the 6-week time course. CTL responses were investigated using the protocol described by Lamers et al.8 to identify and expand CAR-specific clones within the peripheral blood. We compared PBMC stimulated with NT control T cells, GD2-iCAR T cells incorporating iCasp9, or GD2-CAR T cells lacking iCasp9, to determine whether the GD2-CAR construct was immunogenic and whether the inclusion of iCaps9 increased the immunogenicity of the CAR construct. We identified low levels of CAR-specific T cells in month 4 peripheral blood samples for Patient 101, at a frequency of 1–2% in the viable CD3+ population (see Supplementary Figure S7b,c). However, no significant CAR-specificT-cell responses above 1% were detected in samples at other time points for Patient 101, or in any samples from Patient 102, and thus were considered below the limit of detection. Interestingly, the CAR-specific T-cell response at month 4 was detected only in PBMC stimulated with irradiated T cells bearing the GD2-iCAR and not the GD2-CAR, which suggests that any T-cell response in these patients directed against epitopes within the iCasp9 molecule.

Discussion

In the phase 1 CARPETS trial (ACTRN12613000198729), we are investigating adoptive transfer of third-generation GD2-iCAR-PBT in patients with metastatic B-raf kinase (BRAF)-mutant melanoma who concurrently receive dabrafenib with or without trametinib, and BRAF-wildtype melanoma who receive lymphodepleting therapy. The GD2-iCAR consists of CD3ζ, CD28, and OX40 signaling domains coupled to the 14g2a scFv31,32 and an iCasp9 suicide gene.33,34 The same technology is also currently on trial in neuroblastoma patients (GRAIN; NCT01822652).

The failure of adoptively transferred CAR T cells to persist and expand in patients strongly correlates with a lack of antitumor efficacy. There are several proposed theories for this lack of persistence including exhaustion,22 AICD10,12 and immune-mediated deletion.8 In this paper, we have investigated whether any of these factors influence the survival of third-generation GD2-specific CAR T cells currently being tested in phase 1 clinical trials, which is particularly important given the inclusion in the CAR of regions reported to impact on CAR T-cell efficacy such as the 14g2a scFv and the IgG CH2–CH3 spacer, and we have also sought to better define the events occurring following antigen encounter by CAR T cells.

First, we tested GD2-iCAR T cells for evidence of the functional exhaustion resulting from the tonic CAR-signaling that has been reported by others.22 We found that PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 were not constitutively expressed, but that PD-1 and LAG-3 were upregulated transiently during CAR T-cell stimulation. Initial stimulation of CAR T cells resulted in potent cytokine secretion, which was diminished after restimulation, and we observed recovery of IFNγ and TNFα, but not IL-2 production when we blocked PD-1 using pembrolizumab mAb. Loss of IL-2 has been identified as one of the early steps leading to T-cell exhaustion and so may indicate a late-stage effector phenotype.35 A reduction in cytokine secretion was also observed after restimulation of NT controls, indicating that CAR signaling was not solely responsible for the loss of T-cell function. Thus although GD2-iCAR T cells lose some effector functions during longer-term culture and restimulation, the third-generation CAR does not seem to produce the same high levels of tonic CAR signaling and functional exhaustion reported for the GD2-specific, second-generation CD28-CD3ζ CAR36 perhaps because of OX40 coexpression in the third-generation construct. Nevertheless, these results do highlight the importance of rigorous multifunctional analysis of CAR T cells during product development, because immediate effector functions such as target cell lysis and IFNγ secretion observed in vitro may not be an accurate indicator of CAR T-cell efficacy in the clinic.

GD2-iCAR signaling resulted in different kinetics for downstream signaling events, with more rapid calcium flux and signaling molecule phosphorylation, and third-generation CAR of this kind have been previously reported to be more prone to AICD due to the potent stimulation induced.17 Higher basal levels of phosphorylated molecules in resting cells suggests that CAR T cells do have a higher activation state before antigen encounter. Importantly, NT T cells expanded under the same conditions also displayed higher basal levels of signaling molecule phosphorylation and active caspase 3 than unmanipulated T cells from PBMC samples. Thus, we could identify some changes in activation potential and signaling that were due to the effector memory phenotypes generated by ex vivo cell-expansion conditions, as opposed to the intrinsic properties of the third-generation CAR. A central memory or naive/stem-like memory phenotype is associated with superior T-cell persistence whereas an effector memory phenotype has been associated with poor antitumor responses.6,7,37 Consequently, we hypothesize that improvements in ex vivo activation and expansion conditions that promote central memory or stem-like phenotypes may be used to correct some defects in CAR T-cell function observed in this paper. For example, parameters influencing optimal T-cell therapy product development such as cytokine supplementation, stimulation conditions and transduction of defined T-cell subsets have previously been investigated.37,38,39

Our second aim was to investigate whether GD2-iCAR T cells experience activation-induced cell death, as has been reported by others.10 Using an antigen “stress-test” and receptor cross-linking assays, we found that GD2-iCAR T cells had reduced viability after antigen encounter, and lost the ability to kill GD2-specific tumor cell lines.AICD has long been noted in T cells following stimulation.13,15 The iCasp9 molecule has not previously been reported to undergo spontaneous dimerization, however we investigated whether this element contributed to AICD. We found that CAR T cells transduced with an iCasp9-negative vector experienced the same level of rapid caspase 3 activation (<12 hours stimulation) and AICD and this was also observed in NT controls stimulated via CD3 and CD28 receptors, albeit in a lower percentage of T cells. AICD could also be induced in PBMC although the stimulation over a longer time period (>24 hours) was required to observe the effect. Thus, the expression of the third-generation CAR leads to a heightened activation state, which contributes to AICD after repeated antigen stimulation. However, this phenomenon is also seen to some extent in NT T cells with effector memory phenotype and is not caused solely by the CAR-intrinsic elements such as intracellular signaling molecules or iCasp9.

During these investigations, we have found that PD-1 blockade restored CAR T-cell cytokine production and promoted both GD2-iCAR T-cell survival and killing of GD2+ PD-L1+ tumor cells during stress-test assays. Furthermore, we found that activated CAR T cells upregulated the PD-1 ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and the PD-1 receptor-ligand interactions between GD2-iCAR T cells were sufficient to induce AICD in the absence of tumor cells. To determine the ligand responsible for PD-1-dependent AICD, we blocked PD-L1 with blocking antibody and performed siRNA knockdown of PD-1 and PD-L1. This revealed that PD-L1 immune blockade inhibited AICD of CAR T cells, particularly in the presence of receptor cross-linking, while conversely PD-L1 knockdown by siRNA reduced CAR T-cell viability and PD-L2 blockade had no significant effect.

PD-1 and ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, modulate immune responses via inhibition of proliferation and cytokine secretion,40,41 blockade of survival gene expression,42 promotion of Treg differentiation,43 and induction of cell death.44,45 PD-L1 in particular has complex roles in both immune activation and suppression that are still being elucidated. PD-L1 signaling via PD-1 causes inhibition or deletion of activated PD-1+ T cells30,46 whereas signaling via CD80 enables costimulation of naive T cells.47 In addition to this, PD-L1 reportedly mediates reverse signaling within PD-L1+ T cells and protects them from cell death. PD-L1-deficient T cells express lower levels of antiapoptotic molecules and are more susceptible to apoptosis during the contraction phase after antigen-specific expansion.29,48 Early blockade of PD-L1 reportedly enhances antigen-specific T-cell expansion, while late blockade reduces the survival of effector T cells.29 Beneficial PD-L1 reverse signaling has also been identified in the survival of PD-L1+ tumor cells and renders these cells resistant to CTL-mediated and FAS-mediated killing.48 These findings support our observations that PD-L1 blockade improved T-cell survival at early time points postactivation, while conversely PD-L1 knockdown led to reduced survival of CAR T cells. Thus, we hypothesize that PD-L1 signaling may induce AICD in PD-1+ CAR T cells, but also promote survival of PD-L1+ CAR T cells via reverse signaling. It is important to note that PD-1/PD-L1 interactions are likely just one mechanism that contributes to AICD and only the subset of T cells expressing PD-1 will benefit from PD-1 blockade. We also found that FAS, another molecule identified in AICD, was also highly expressed on GD2-iCAR T cells and FASL was upregulated during stimulation. Blockade of FAS also promoted CAR T-cell survival, albeit at the expense of some CAR T-cell cytotoxic function. Therefore, we have identified a novel role for PD-1/PD-L1 interactions in AICD of CAR T cells, in addition to the FAS/FASL interactions previously identified by others10

One limitation of this study is that we lacked first- or second-generation GD2-CAR constructs, or constructs with different GD2-affinities, to compare to our third-generation CAR. It would be interesting to investigate to what extent re-engineering of CAR constructs would influence AICD and the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis. We hypothesize that the strength of CAR-mediated activation determines CAR T-cell deletion versus persistence, and may well play a role in the memory phenotype and functional potential of surviving T cells. In this GD2-CAR, it is possible that removing the OX40 signaling domain entirely,18 replacing it with the 41BB signaling domain24 or 41BB ligand49 as reported by others, may reduce or prevent AICD and/or PD-1-mediated suppression.

We have applied our understanding of our in vitro results to an analysis of peripheral blood samples derived from patients enrolled in the ongoing CARPETS clinical trial. The limited number of patients enrolled thus far, means the results presented are descriptive and cannot be used to form definitive conclusions. However, we identified upregulated expression of both PD-1 and PD-L1 on a subset of peripheral-blood GD2-iCAR T cells, a detectable GD2-iCAR+ population declined in all patients beyond day 28 postinfusion, and failed to persist in Patients 101 and 102, suggesting that mechanisms of CART-cell deletion we have identified in vitro may also be at play in vivo. Deletion may occur after GD2 antigen encounter or from nonantigen specific activation, for example, after engagement of the IgG CH2–CH3 spacer region with FcyR-bearing immune cells,10,12 and this requires further investigation. However, we propose that the timing of peak serum cytokines in CARPETS patients (days 7–28) may indicate antigen encounter because they occur at a similar time (~day 17) to the peaks of serum IFNy and IL-6 observed in leukemia patients treated with CD19-specific CAR T-cells,1 albeit at much lower concentrations.

Another hypothesis for lack of persistence is that a CAR T-cell-specific immune response targets the mouse-derived 14g2a scFv, the retroviral sequences, or the modified iCasp9 gene and cause immune-mediated deletion of CAR T cells. However, the low level and delayed timing of CAR-specific T-cell responses detected probably does not account for the reduction in detectable circulating CAR T cells by day 28 postinfusion. Furthermore, an increase in titer of (pre-existing) HAMA was detected in only one patient postinfusion, and this patient (201) is currently the only patient with detectable CAR T cells at month 4. Hence, we propose that early CAR T-cell deletion is more likely related to AICD than to postinfusion anti-CAR transgene immune responses.

The lack of persistence may be overcome with preinfusion lymphodepleting chemotherapy, which is known to have multiple effects on both tumor and immune environments, including the removal of suppressive cells and the provision of homeostatic cytokines to newly infused cells.50 The third patient enrolled in the CARPETS trial (Patient 201) received fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FluCy) conditioning as part of the CARPETS protocol and we immediately observed increased expansion of CAR T cells, however CAR T cells then declined from day 14. These data indicate that although the lymphodepleting chemotherapy supported GD2-iCAR T-cell expansion, the expanded population of adoptively transferred cells did not persist, perhaps because of active T-cell deletion. However at this stage, our results can only be descriptive until more patients are enrolled to the study.

Mounting clinical evidence indicates that pre-existing T-cell immunity is required for therapeutically effective PD-1 and PD-L1 blockade.20,36 CAR T cells may provide a source of primed immune effectors when endogenous responses are insufficient. Here, we have identified important roles for PD-1 interactions in the suppression of CAR T-cell effector functions as well as a novel role in CAR T-cell AICD, and these findings complement other preclinical studies.21 In a recent protocol amendment for the GRAIN trial of GD2-specific CAR T cells in neuroblastoma patients, concurrent treatment with anti-PD-1 mAb has been allowed. The current study therefore further supports the rationale for combining anti-PD-1 mAb and CAR T-cell therapy, which we hypothesize may also benefit patients with tumors lacking PD-L1 expression if the CAR T cells express PD-L1. We therefore propose to incorporate anti-PD-1 mAb combination therapy into the next cohort of patients enrolled in the CARPETS clinical trial.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects. Blood samples were obtained from patients with melanoma who provided written informed consent. The Royal Adelaide Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee approved the research protocols for the CARPETS trial (ACTRN12613000198729). In addition to the initial blood donation, patients enrolled in the CARPETS trial donated blood for analysis of persistence and immune phenotyping at days 0, 7, 14, 28, and 42 postadministration of autologous GD2-specific CAR T cells (GD2-iCAR PBT). Two metastatic melanoma patients (101 and 102), who did not have prior lymphodepletion, received the lowest GD2-iCAR-PBT dose level of 10 million cells/m2. Each patient had a tumor containing a V600 BRAF mutation and so received concurrent dabrafenib at the time of PBMC procurement and during the 6-week study evaluation period postinfusion. After a protocol amendment to allow concurrent treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib for patients with V600 BRAF mutant melanoma and lymphodepleting chemotherapy for patients with V600 BRAF mutation-negative melanoma, patients were enrolled at the second dose level. A third metastatic melanoma patient (201) had a V600 BRAF mutation-negative melanoma and had not had previous systemic therapy for melanoma. This patient received the second dose level of 20 million GD2-iCAR-PBT cells/m2 on day 0 after lymphodepletion with fludarabine 30 mg/m2 on days −4, −3, and −2 and IV cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 on days −4 and −3. A fourth patient (203) with metastatic V600 BRAF melanoma received the second dose level of 20 million GD2-iCAR-PBT cells/m2 concurrent with dabrafenib and trametinib.

Cell lines and patient-derived primary cells. LAN-1 (neuroblastoma cell line), M238, M238R1, and SK-Mel-28 (melanoma cell lines) were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-Glutamine, and 1% Penicillin/Gentamicin (IDL, Adelaide, Australia). M238 and M238R1 cell lines were gratefully received from Roger Lo (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA). To generate GD2-iCAR PBT, patient PBMC were purified by density gradient separation, activated for 3 days with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (Miltenyi Biotec, Sydney, Australia), transduced with the GD2-iCAR retroviral vector SFG.iCasp9.2A.14g2a.CD28.OX40.zeta supernatant (CAGT, BCM, Houston, TX), and then expanded for 10–14 days in IL-7 and IL-15 (Miltenyi Biotec, Sydney, Australia) and cryopreserved before use, as described previously.23 Nontransduced (NT) controls were activated and cultured in the same manner, but without retrovirus. Patient PBMC pre- and postadministration were purified and cryopreserved before analysis, as described previously. All cells were thawed and rested overnight before analysis in in vitro assays.

Flow cytometry. Cells were analyzed on BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, North Ryde, Australia) and FlowJo Software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). Isotype and FMO controls were used in each assay to establish negative gates and cells were incubated with Human Fc-block (BD Biosciences, North Ryde, Australia) for 5 minutes before staining. All gating strategies and representative data sets are shown in Supplementary Figures S1–S6. Staining was performed as described previously,27 with 1A7 (anti-idiotypic mAb for GD2-iCAR purified in house) and PE-conjugated secondary (BD Biosciences) used to detect CAR+ T cells in all instances. To detect cytokine secretion, cytokine bead arrays were performed using a BD Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Assay Kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). For proliferation assays, cells were stained with 1.5 µmol/l Cell Trace Violet (Life Technologies, Scoresby, Australia) before stimulation. For ratiometric calcium flux detection, CAR T cells were stained with 4 μmol/l Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), 10 μg/ml Fura Red AM (Molecular Probes), and 0.02% Pluronic F-127 (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA) as described by others. Cell samples were recorded for 30 seconds to establish a baseline and then anti-CAR (10 μg/ml), anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml), anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml) or cross-linking secondary antibodies (10 μg/ml) were added, and recordings made for a further 270 seconds. Ionomycin was used as a positive control, and some cells were prestained with primary antibodies for 30 minutes before adding crosslinking secondary antibody. For signaling molecule phosporylation detection, anti-pERK1/2-FITC, anti-pAKT-bv421, or anti-pSTAT6-FITC anti-pSTAT5-bv421 (BD Biosciences) were used. For viability and activation analyses, cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC, CD69-Pecy7, CD25-APC-Cy7, and DAPI (Sigma Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia). GD2 expression on tumor cells was detected with anti-GD2-APC (14g2a clone, BD Biosciences).

In vitro functional assays. For stimulation assays, cells were stimulated with plate-bound 1 µg/ml anti-CD3/CD28 (Miltenyi Biotech) or 2 µg/ml 1A7 for 3 days, cells and supernatants were collected for analysis by flow cytometry, and remaining cells were transferred to uncoated wells with fresh media. For restimulation, cells were stimulated for 3 days, rested for 4 days, and then restimulated for 3 days as above. For crosslinking assays, cells were cultured with either 1 µg/ml soluble 1A7 or 1 µg/ml soluble 1A7 or 10 µg/ml soluble antimouse IgG secondary. For coculture “stress-test” assays, tumor and CAR T cells were cultured at a 1:1 ratio, as described by others.10 Every 24 hours, CAR T cells were removed and replated onto fresh tumor cells at a 1:1 ratio. Remaining tumor cells and a sample of CAR T cells were retained at each 24-hour time point for analysis of viability by flow cytometry. Cytotoxicity assays were performed as described previously,27 with GD2-iCAR PBT cocultured with 51Cr-labeled LAN-1 neuroblastoma, M238, or M238R1 melanoma cells, and autologous PHA-blasts or SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells (as negative controls) for 6 hours before 51Cr-release was analyzed.

Detection of CAR-specific immune responses. Human antimouse antibody was assayed using patient serum collected pre and post CART-cell infusion using a HAMA ELISA kit (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CAR-specific immune responses were assayed as described by Lamers et al. Briefly, PBMC from preadministration, day 28, day 42, and month 4 timepoints were cultured with autologous, irradiated CAR T cells or NT control T cells as feeder cells at a 4:1 ratio. New feeder cells were added every 7 days for 4 weeks. We used CD107a (BD Biosciences) staining as a marker of degranulation to assess responses. Responses were considered negative when the flow cytometry assay yielded a net %CD107a+ population of <1%, based on the background observed for PBMC stimulated with NT control T cells.

Blockade or knockdown of PD-1, PD-L1, or FAS. In selected assays, 20 µg/ml pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), 10 µg/ml anti-PD-L1-neutralizing antibody MIH1 10 µg/ml anti-PD-L2 neutralizing antibody MIH18 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA),51 and 10 µg/ml anti-FAS-neutralizing antibody ZB452 (Millipore, Billercia, MA), were included from the initiation of culture. siRNA designed against the PD-L1, PD-1, and FAS human DNA sequence (Sigma Aldrich, Castle Hill, Australia) were introduced into cells by electroporation and knock down of target molecules was confirmed by flow cytometry. Cells electroporated with scrambled-siRNA were used as a negative control.

Statistical analyses. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Version 6.0d (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (for single variable data) or two-way analysis of variance (for two variable data) and Bonferroni multiple comparison posttests. Significance is represented on graphs as *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Gating strategy for activation and exhaustion markers. Figure S2. Investigating CAR T-cell function during primary and repeated stimulation. Figure S3. Intracellular signalling after stimulation of CAR T cells. Figure S4. Repeated antigen stimulation assay. Figure S5. Expression of PD-L1, FAS and FASL on CAR T cells, and effects of blocking these molecules during stimulation. Figure S6. GD2-iCAR PBT persistence and immune phenotype in patients. Figure S7. CAR-specific immune responses in patients postCAR T-cell infusion.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support from NHMRC Project Grant APP1010386 and the Therapeutic Innovation Australia Researcher Access Scheme. We thank Zhuyong Mei, Oumar Diouf, Adrian Gee, and Debbie Lyons from CAGT, Baylor College of Medicine for assistance with retroviral vector production and shipping and associated protocols. We also thank Cara Fraser for assistance with standard operating procedures, Smita Hiwase, Pam Dyson and Kerry Munro at the Therapeutic Products Facility, SA Pathology, and Andy Flies from the Experimental Therapeutics Laboratory, University of South Australia.

Supplementary Material

References

- Porter, DL, Levine, BL, Kalos, M, Bagg, A and June, CH (2011). Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 365: 725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp, SA, Kalos, M, Barrett, D, Aplenc, R, Porter, DL, Rheingold, SR et al. (2013). Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368: 1509–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw, MH, Westwood, JA, Parker, LL, Wang, G, Eshhar, Z, Mavroukakis, SA et al. (2006). A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res 12(20 Pt 1): 6106–6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis, CU, Savoldo, B, Dotti, G, Pule, M, Yvon, E, Myers, GD et al. (2011). Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood 118: 6050–6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, CH, Sleijfer, S, van Steenbergen, S, van Elzakker, P, van Krimpen, B, Groot, C et al. (2013). Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with CAIX CAR-engineered T cells: clinical evaluation and management of on-target toxicity. Mol Ther 21: 904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y, Tan, Y, Ou, R, Zhong, Q, Zheng, L, Du, Y et al. (2015). Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for B-cell malignancies: a systematic review of efficacy and safety in clinical trials. Eur J Haematol 96: 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pule, MA, Savoldo, B, Myers, GD, Rossig, C, Russell, HV, Dotti, G et al. (2008). Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med 14: 1264–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, CH, Willemsen, R, van Elzakker, P, van Steenbergen-Langeveld, S, Broertjes, M, Oosterwijk-Wakka, J et al. (2011). Immune responses to transgene and retroviral vector in patients treated with ex vivo-engineered T cells. Blood 117: 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, MC, Popplewell, L, Cooper, LJ, DiGiusto, D, Kalos, M, Ostberg, JR et al. (2010). Antitransgene rejection responses contribute to attenuated persistence of adoptively transferred CD20/CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor redirected T cells in humans. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16: 1245–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künkele, A, Johnson, AJ, Rolczynski, LS, Chang, CA, Hoglund, V, Kelly-Spratt, KS et al. (2015). Functional tuning of CARs reveals signaling threshold above which CD8+ CTL antitumor potency is attenuated due to cell Fas-FasL-dependent AICD. Cancer Immunol Res 3: 368–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudecek, M, Sommermeyer, D, Kosasih, PL, Silva-Benedict, A, Liu, L, Rader, C et al. (2015). The nonsignaling extracellular spacer domain of chimeric antigen receptors is decisive for in vivo antitumor activity. Cancer Immunol Res 3: 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach, A, Hombach, AA and Abken, H (2010). Adoptive immunotherapy with genetically engineered T cells: modification of the IgG1 Fc ‘spacer' domain in the extracellular moiety of chimeric antigen receptors avoids ‘off-target' activation and unintended initiation of an innate immune response. Gene Ther 17: 1206–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, DR, Droin, N and Pinkoski, M (2003). Activation-induced cell death in T cells. Immunol Rev 193: 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, S, Chhabra, A, Chattopadhyay, S, Dorsky, DI, Chakraborty, NG and Mukherji, B (2004). Rescuing melanoma epitope-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes from activation-induced cell death, by SP600125, an inhibitor of JNK: implications in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunol 173: 6017–6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher, S, Toomey, D, Condron, C and Bouchier-Hayes, D (2002). Activation-induced cell death: the controversial role of Fas and Fas ligand in immune privilege and tumour counterattack. Immunol Cell Biol 80: 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, A (2010). Mitochondria-centric activation induced cell death of cytolytic T lymphocytes and its implications for cancer immunotherapy. Vaccine 28: 4566–4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach, AA, Rappl, G and Abken, H (2013). Arming cytokine-induced killer cells with chimeric antigen receptors: CD28 outperforms combined CD28-OX40 “super-stimulation”. Mol Ther 21: 2268–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speiser, DE, Utzschneider, DT, Oberle, SG, Münz, C, Romero, P and Zehn, D (2014). T cell differentiation in chronic infection and cancer: functional adaptation or exhaustion? Nat Rev Immunol 14: 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, J, Gnjatic, S, Mhawech-Fauceglia, P, Beck, A, Miller, A, Tsuji, T et al. (2010). Tumor-infiltrating NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ T cells are negatively regulated by LAG-3 and PD-1 in human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 7875–7880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumeh, PC, Harview, CL, Yearley, JH, Shintaku, IP, Taylor, EJ, Robert, L et al. (2014). PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515: 568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, LB, Devaud, C, Duong, CP, Yong, CS, Beavis, PA, Haynes, NM et al. (2013). Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy potently enhances the eradication of established tumors by gene-modified T cells. Clin Cancer Res 19: 5636–5646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, AH, Haso, WM, Shern, JF, Wanhainen, KM, Murgai, M, Ingaramo, M et al. (2015). 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Med 21: 581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargett, T and Brown, MP (2015). Different cytokine and stimulation conditions influence the expansion and immune phenotype of third-generation chimeric antigen receptor T cells specific for tumor antigen GD2. Cytotherapy 17: 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, AD, Schuster, K, Gadiot, J, Borkner, L, Daebritz, H, Schmitt, C et al. (2012). Reduced tumor-antigen density leads to PD-1/PD-L1-mediated impairment of partially exhausted CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 42: 662–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, J, Rieger, A, Pickl, WF, Zlabinger, G, Grabmeier-Pfistershammer, K and Steinberger, P (2013). TIM-3 does not act as a receptor for galectin-9. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigault, MJ, Lee, J, Basil, MC, Carpenito, C, Motohashi, S, Scholler, J et al. (2015). Identification of chimeric antigen receptors that mediate constitutive or inducible proliferation of T cells. Cancer Immunol Res 3: 356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargett, T, Fraser, CK, Dotti, G, Yvon, ES and Brown, MP (2015). BRAF and MEK inhibition variably affect GD2-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell function in vitro. J Immunother 38: 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, V, Savoldo, B, Quintarelli, C, Mahendravada, A, Zhang, M, Vera, J et al. (2010). Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia 24: 1160–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulko, V, Harris, KJ, Liu, X, Gibbons, RM, Harrington, SM, Krco, CJ et al. (2011). B7-h1 expressed by activated CD8 T cells is essential for their survival. J Immunol 187: 5606–5614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, RM, Liu, X, Pulko, V, Harrington, SM, Krco, CJ, Kwon, ED et al. (2012). B7-H1 limits the entry of effector CD8(+) T cells to the memory pool by upregulating Bim. Oncoimmunology 1: 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulè, MA, Straathof, KC, Dotti, G, Heslop, HE, Rooney, CM and Brenner, MK (2005). A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol Ther 12: 933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yvon, E, Del Vecchio, M, Savoldo, B, Hoyos, V, Dutour, A, Anichini, A et al. (2009). Immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma using genetically engineered GD2-specific T cells. Clin Cancer Res 15: 5852–5860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasi, A, Tey, SK, Dotti, G, Fujita, Y, Kennedy-Nasser, A, Martinez, C et al. (2011). Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med 365: 1673–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargett, T and Brown, MP (2014). The inducible caspase-9 suicide gene system as a “safety switch” to limit on-target, off-tumor toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Front Pharmacol 5: 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry, EJ (2011). T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 12: 492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, RS, Soria, JC, Kowanetz, M, Fine, GD, Hamid, O, Gordon, MS et al. (2014). Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 515: 563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y, Zhang, M, Ramos, CA, Durett, A, Liu, E, Dakhova, O et al. (2014). Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 123: 3750–3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, DM, Singh, N, Liu, X, Jiang, S, June, CH, Grupp, SA et al. (2014). Relation of clinical culture method to T-cell memory status and efficacy in xenograft models of adoptive immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 16: 619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli, E, Gattinoni, L, Roberto, A, Mavilio, D, Price, DA, Restifo, NP et al. (2013). Identification, isolation and in vitro expansion of human and nonhuman primate T stem cell memory cells. Nat Protoc 8: 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchman, Y, Wood, CR, Chernova, T, Chaudhary, D, Borde, M, Chernova, I et al. (2001). PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol 2: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butte, MJ, Keir, ME, Phamduy, TB, Sharpe, AH and Freeman, GJ (2007). Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 27: 111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemnitz, JM, Parry, RV, Nichols, KE, June, CH and Riley, JL (2004). SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol 173: 945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarnath, S, Mangus, CW, Wang, JC, Wei, F, He, A, Kapoor, V et al. (2011). The PDL1-PD1 axis converts human TH1 cells into regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med 3: 111ra120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Y, Agata, Y, Shibahara, K and Honjo, T (1992). Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J 11: 3887–3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H, Strome, SE, Salomao, DR, Tamura, H, Hirano, F, Flies, DB et al. (2002). Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med 8: 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchman, YE, Liang, SC, Wu, Y, Chernova, T, Sobel, RA, Klemm, M et al. (2004). PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10691–10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, JH, Johanns, TM, Ertelt, JM and Way, SS (2008). PDL-1 blockade impedes T cell expansion and protective immunity primed by attenuated Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol 180: 7553–7557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, T, Yao, S, Zhu, G, Flies, AS, Flies, SJ and Chen, L (2008). B7-H1 is a ubiquitous antiapoptotic receptor on cancer cells. Blood 111: 3635–3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z, Condomines, M, van der Stegen, SJ, Perna, F, Kloss, CC, Gunset, G et al. (2015). Structural design of engineered costimulation determines tumor rejection kinetics and persistence of CAR T cells. Cancer Cell 28: 415–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff, CA, Khong, HT, Antony, PA, Palmer, DC and Restifo, NP (2005). Sinks, suppressors and antigen presenters: how lymphodepletion enhances T cell-mediated tumor immunotherapy. Trends Immunol 26: 111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamatsu, T, Schust, DJ, Sugimoto, J and Barrier, BF (2009). Human decidual stromal cells suppress cytokine secretion by allogenic CD4+ T cells via PD-1 ligand interactions. Hum Reprod 24: 3160–3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meli, M, D'Alessandro, N, Tolomeo, M, Rausa, L, Notarbartolo, M and Dusonchet, L (2003). NF-kappaB inhibition restores sensitivity to Fas-mediated apoptosis in lymphoma cell lines. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1010: 232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.