Abstract

(5Z)-4-Bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone (furanone) from the red marine alga Delisea pulchra was found previously to inhibit the growth, swarming, and biofilm formation of gram-positive bacteria. Using the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis as a test organism, we observed cell killing by 20 μg of furanone per ml, while 5 μg of furanone per ml inhibited growth approximately twofold without killing the cells. To discover the mechanism of this inhibition on a genetic level and to investigate furanone as a novel antibiotic, full-genome DNA microarrays were used to analyze the gene expression profiles of B. subtilis grown with and without 5 μg of furanone per ml. This agent induced 92 genes more than fivefold (P < 0.05) and repressed 15 genes more than fivefold (P < 0.05). The induced genes include genes involved in stress responses (such as the class III heat shock genes clpC, clpE, and ctsR and the class I heat shock genes groES, but no class II or IV heat shock genes), fatty acid biosynthesis, lichenan degradation, transport, and metabolism, as well as 59 genes with unknown functions. The microarray results for four genes were confirmed by RNA dot blotting. Mutation of a stress response gene, clpC, caused B. subtilis to be much more sensitive to 5 μg of furanone per ml (there was no growth in 8 h, while the wild-type strain grew to the stationary phase in 8 h) and confirmed the importance of the induction of this gene as identified by the microarray analysis.

Gram-positive bacteria are important causes of infectious diseases and are responsible for more than 60% of the nosocomial bloodstream infections in the United States, while gram-negative bacteria are responsible for only 27% of such infections (7). Hence, it would be beneficial to find novel antimicrobials for gram-positive bacteria, and natural brominated furanones hold great potential.

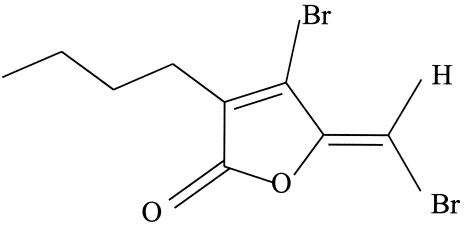

Recently, several brominated furanones from the marine alga Delisea pulchra have been shown to inhibit the quorum sensing (control of gene expression by sensing the bacterial population [3, 34]) of gram-negative bacteria by affecting both the species-specific (16) and non-species-specific (26) quorum-sensing signals autoinducer 1 (AI-1) (acylated homoserine lactones) and AI-2, respectively. As a consequence, these agents inhibit swarming and biofilm formation of gram-negative bacteria without affecting cell growth (10, 12, 24, 26). Interestingly, the furanones were also found to inhibit growth of gram-positive bacteria at concentrations not toxic to mammalian cells (14). One of the best-studied natural furanones of D. pulchra,(5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone(referred to as furanone below) (Fig. 1), inhibits the growth, swarming, and biofilm formation of Bacillus subtilis (25) in a manner distinct from that of Pseudomonas aeruginosa since gram-positive bacteria do not have an acylated homoserine lactone signaling system (3).

FIG. 1.

Structure of furanone.

While there have been several studies of the inhibitory effect of furanone on the phenotypes of gram-negative bacteria (16, 24, 26), little is known about the mechanism by which furanone inhibits the growth of gram-positive bacteria. To initiate an investigation of this mechanism on a genetic basis, DNA microarrays were used here to obtain the gene expression profiles of a model gram-positive bacterium, B. subtilis, with and without furanone. DNA microarrays have been used to monitor global gene expression profiles in response to different stimuli (31), including heat shock and other stresses (11, 38, 41), quorum sensing (5, 32), anaerobic metabolism (39), sporulation (8), and biofilm formation (26b, 28, 33, 37). DNA microarrays have also been used to study the global gene expression of B. subtilis in response to the antibiotic bacitracin (19). The microarray data obtained in the present study suggest that some type of stress response was induced by the furanone, and a mutant with a deletion in one of the induced stress response genes, clpC, was found to be more sensitive to growth inhibition by furanone. The identified induced genes are also candidates for drug discovery because they may be general genes used by gram-positive bacteria to thwart antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture medium.

Wild-type B. subtilis JH642 (pheA1 trpC2) was obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Columbus, Ohio). B. subtilis 168 (trpC2) and its clpC mutant B. subtilis QB4756 (trpC2 ΔclpC::spc) were kindly provided by Tarek Msadek (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (27) containing 10 g of tryptone per liter, 5 g of yeast extract per liter, and 10 g of NaCl per liter was used to culture the B. subtilis strains.

Furanone synthesis.

Furanone (Fig. 1) was synthesized by the method of Beechan and Sims (4), as well as by the four-step method of Manny et al. (18), with the following three changes: (i) the decarboxylation step was conducted by refluxing in benzene rather than in toluene, (ii) the lactone formation step (the last step) was conducted in a water bath (100°C) rather than in an oil bath (110 to 120°C), and (iii) the furanone was purified by column chromatography with hexane and ethyl acetate at a ratio of 100:1 (2.5- by 60-cm column; Spectrum Chromatography, Houston, Tex.). The structure of the purified product was verified by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (DRX-400MHz; Bruker Billerica, Mass.) (6.24 single peak, vinylidene; 2.39 triple peaks, coupling constant J = 7.2 Hz, allylic methylene; 0.93 triple peaks, coupling constant J = 7.2 Hz, terminal methyl) and infrared analysis (Nicolet-Magna-IR 560; Nicolet-Magna, Madison, Wis.) (reciprocal absorbing wavelengths, 2,958, 1,793, 1,610, 1,276, 1,108, and 1,030 cm−1) by comparison with previously published furanone spectra (4, 18). The identity of the furanone product synthesized by the method of Manny et al. (18) and the product synthesized by the method of Beechan and Sims (4) was also verified by thin-layer chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate ratio, 20:1; Rf, 0.8; Silica Gel 60, F-254; Selecto Scientific, Suwanee, Ga.). Furanone stock solutions (14.9 mg/ml in 95% ethanol) were stored at 4°C.

Furanone and B. subtilis gene expression studied with DNA microarrays.

To identify which genes are affected by addition of furanone to gram-positive bacteria, B. subtilis JH642 was grown in LB medium overnight at 37°C and diluted 1:100 into fresh 37°C LB medium. When the cells reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8, the culture was split equally into three portions, and 0, 5, or 20 μg of furanone per ml was added (the same amount of ethanol was added to all samples to eliminate the effect of solvent). Furanone at a concentration of 5 μg/ml decreased the rate of cell growth approximately twofold, but it did not kill the cells, while 20 μg of furanone per ml had a stronger inhibitory effect (see Results). After incubation for 15 min, the cells were harvested by centrifugation for 15 s (maximum speed) in −80°C mini bead beater tubes (catalog no. 10832; Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). The cell pellets were flash frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath and stored at −80°C until RNA was isolated.

Total RNA isolation.

To lyse the cells, 1.0 ml of RLT buffer (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and 0.2 ml of 0.1-mm zirconia/silica beads (Biospec) were added to the frozen tubes containing cell pellets. The tubes were closed tightly and beaten for 60 s at the maximum speed in a mini bead beater (catalog no. 3110BX; Biospec). Total RNA was isolated by using the protocol of an RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN), including on-column DNase digestion with RNase-free DNase I (QIAGEN). The OD260 was used to quantify the RNA yield, and the OD280 was used to quantify the protein; hence, OD260/OD280 and 23S rRNA/16S rRNA ratios were determined to check the purity and integrity of the RNA (RNeasy mini kit handbook; QIAGEN).

DNA microarrays.

The B. subtilis DNA microarrays were prepared as described previously (39). Each gene probe was synthesized by PCR and was the size of the full open reading frame (200 to 2,000 nucleotides). The double-stranded PCR products were denatured in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide and spotted onto aminosilane slides (Full Moon Biosystems, Sunnyvale, Calif.) as probes to hybridize with the mRNA-derived cDNA samples. It has been shown that each array can detect 4,020 of the 4,100 B. subtilis open reading frames (39). Each gene has two spots per slide.

Synthesis of Cy3- or Cy5-labeled cDNA.

To convert the total RNA into labeled cDNA, reverse transcription was performed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube to which 10 μg of total RNA and 6 μg of random hexamer primers (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) were added, and the volume was adjusted to 24 μl with RNase-free water (Invitrogen Corp.). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 70°C and then for 10 min at room temperature for annealing. To this mixture, 8 μl of 5× SuperScript II reaction buffer (Invitrogen Corp.), 4 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol (Invitrogen Corp.), 1 μl of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture (2 mM dATP, 2 mM dGTP, 2 mM dTTP, and 1 mM dCTP), 1 μl of 0.5 mM Cy3- or Cy5-labeled dCTP (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.), and 2 μl of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (10 U/μl; Invitrogen Corp.) were added to make cDNA. cDNA synthesis was conducted at 42°C for 2 h and stopped by heating at 94°C for 5 min. After cDNA synthesis, the RNA template was removed with 2 μl of 2.5 M NaOH. The pH was neutralized with 10 μl of 2 M HEPES buffer, and the cDNA was purified with a Qiaquick PCR mini kit (QIAGEN, Inc.). The efficiency of labeling was checked by determining the absorbance at 260 nm for the cDNA concentration, the absorbance at 550 nm for Cy3 incorporation, and the absorbance at 650 nm for Cy5 incorporation.

Hybridization and washing.

The control RNA samples (containing no furanone) and the test RNA samples (containing 5 μg of furanone per ml) were each labeled with both the Cy3 and Cy5 dyes to remove artifacts related to different labeling efficiencies. Each experiment required two slides; the Cy3-labeled no-furanone sample and the Cy5-labeled sample with furanone were hybridized on the first slide, and, similarly, the Cy5-labeled no-furanone sample and the Cy3-labeled sample with furanone were hybridized on the second slide. Since each gene had two spots on a slide, the two hybridizations generated eight data points for each gene (four points for the furanone sample and four points for the no-furanone sample).

The DNA microarrays were incubated in a prehybridization solution containing 3.5× SSC (Invitrogen), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Invitrogen), and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Invitrogen) at 45°C for 20 min (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate). The arrays were rinsed with double-distilled water and spun dry by centrifugation. The labeled cDNA (6 μg) was concentrated to 10 μl (total volume) and mixed with 10 μl of 4× cDNA hybridization solution (Full Moon Biosystems) and 20 μl of formamide (EM Science, Gibbstown, N.J.). The hybridization mixture was heated at 95°C for 2 min and added to the DNA microarrays; each array was covered with a coverslip (Corning, Big Flats, N.Y.) and incubated overnight at 37°C for hybridization. When the hybridization was finished, the coverslips were removed in 1× SSC-0.1% SDS at room temperature, and the arrays were washed once for 5 min in 1× SSC-0.1% SDS at 40°C, twice for 10 min in 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS at 40°C, and twice for 1 min in 0.1× SSC at 40°C. The arrays were quickly rinsed by dipping them in room temperature double-distilled water and then spun dry by centrifugation.

Image and data analysis.

The hybridized slides were scanned with a Generation III array scanner (Molecular Dynamics Corp.), and 570 and 670 nm were used to quantify the cDNA probes labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 separately. The signal was quantified with Array Vision 4.0 or 6.0 software (Imaging Research, St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada). Genes were identified as differentially expressed (i.e., induced or repressed) if the expression ratio was greater than fivefold (one standard deviation) and the P value (as determined by a t test) was less than 0.05; in a few cases some genes did not meet these criteria and are listed below as up-regulated. Including the P value criterion ensured the reliability of the induced-repressed gene list. P values were calculated with log-transformed, normalized intensities. Normalization was relative to the median total fluorescence intensity per slide per channel. The gene functions were obtained from the database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

RNA dot blotting.

DNA probes for four representative genes, clpC, ctsR, groES, and pyrF, were synthesized by using a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). Most of the probes were 400 bp long; the only exception was the groES probe, which was only 276 bp long due to the small size of the groES genes. Total RNA (1.25, 2.5, or 5 μg for each sample) from independent experiments (which were different from the experiments used to harvest RNA for the DNA microarrays) was blotted on positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ridgefield, Conn.) by using a Bio-Dot microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). RNA was fixed by baking the membranes for 2 h at 80°C, and about 400 ng of excess DNA probes was denatured in boiling water for 5 min before hybridization to RNA (serial dilutions of RNA samples were tested in each blot to ensure that there was an excess of the DNA probes). Hybridization (50°C, 16 h) and washes were conducted by following the protocol for DIG labeling and detection (Roche Applied Science). To detect the signal, disodium 3-(4-methoxyspiro{1,2-dioxetane-3,2-(5-chloro)tricyclo [3.3.1.1,7] decan}-4-yl) phenyl phosphate (Roche Applied Science) was used as a substrate to give chemiluminescence, and the light was recorded with Biomax X-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Sensitivity of B. subtilis to furanone due to the clpC mutation.

To each 250-ml shake flask, 25 ml of LB medium and 0, 5, 20, or 40 μg of furanone (14.9 mg/ml in 95% ethanol) per ml were added. Appropriate amounts of ethanol were added to eliminate the effect of solvent. The cultures were inoculated directly from glycerol stocks (15 μl for wild-type B. subtilis 168 and 30 μl for the clpC mutant B. subtilis QB4756 because the density of the mutant in stocks was lower due to its defect in stationary-phase growth [21]). The growth of both strains with different concentrations of furanone was monitored by measuring the OD600, and the specific growth rates were calculated. These experiments were conducted in duplicate.

Epifluorescence microscopy.

Ten milliliters of LB broth in a 100-ml shake flask was inoculated with 100 μl of an overnight culture of B. subtilis 168. Growth at 37°C was monitored, and when the OD600 reached 0.2, either no furanone or 40 μg of furanone per ml was added (the same amount of ethanol was added to both samples). The fixation method was based on the method of Amann et al. (1). Aliquots (250 μl) were removed from the culture flasks 30 and 60 min after the addition of furanone and then mixed immediately with 750 μl of 4% paraformaldehyde-phosphate-buffered saline (130 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer; pH 7.2) and incubated at 4°C for 3 h. Cells were centrifuged and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline. Fixed cells were resuspended in a phosphate-buffered saline-100% ethanol solution (1:1, vol/vol) and stored at −20°C. Fixed cells were stained with 1 μg of4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) per ml in 50% glycerol.

DAPI-stained cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy by using a DMLB microscope with an N PLAN 100×/1.25 numerical aperture oil immersion objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany); the light source for UV excitation (450 to 490 nm) was a 100-W mercury lamp. Images were captured with a DC100 digital camera by utilizing the IM50 software package (version 1.20, release 9; Leica Microsystems). Twenty fields were analyzed for each treatment.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

As described above for epifluorescence microscopy, when the OD600 reached 0.2, no furanone or 20 μg of furanone per ml was added to a B. subtilis 168 culture (the same amount of ethanol was added to both samples). Aliquots (330 μl) were removed from the culture flasks 15 min after the addition of furanone, and the cells were stained with a LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) by adding 1 μl of SYTO 9 dye (from a 3.34 mM SYTO 9 stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide) and 1 μl of propidium iodide (from a 20 mM propidium iodide stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide). The mixture was then incubated for 15 min.

The stained cells were viewed by confocal laser scanning microscopy by using a DM IRB microscope with a PL APO 100×/1.4 numerical aperture oil immersion objective (true confocal system; TCS SP; Leica Microsystems). The excitation wavelength was 488 nm (argon laser), and fluorescence signals were collected in two photomultiplier tubes set at collection ranges of 497 to 532 nm for SYTO 9 (green) and 608 to 655 nm for propidium iodide (red).

RESULTS

Furanone caused changes in gene expression in B. subtilis.

To study growth inhibition of gram-positive bacteria caused by furanone, DNA microarrays were used to analyze the gene expression profiles of the model gram-positive species B. subtilis with and without furanone treatment. B. subtilis cells at the late exponential phase (OD600, 0.8) were incubated with and without 5 μg of furanone per ml for 15 min; this concentration of furanone was chosen because it inhibited cell growth approximately twofold without killing the cells (see below). Under these conditions furanone induced 92 genes (Table 1) and repressed 15 genes (Table 2) more than fivefold. Genes in the same operons were induced together (e.g., of the 30 induced genes with known functions, 6 operons were induced, including the rbsABCDKR genes that were individually induced 12- to 46-fold) or repressed together (e.g., pyrABDDIIEF were all repressed 7- to 50-fold), indicating that the RNA was of good quality and the hybridization was efficient.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis genes induced by 5 μg of furanone per ml

| Gene | Induction expression ratio | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | ||

| acoR | 192.3 | Positive regulation of the acetoin dehydrogenase operon (acoABCL) |

| acuB | 7.1 | Acetoin utilization |

| glpF | 34.7 | Glycerol utilization |

| glpK | 6.3 | Glycerol utilization |

| licH | 67.3 | Lichenan degradation product utilization |

| Fatty acid biosynthesis | ||

| fabD | 8.4 | Malonyl coenzyme A-acyl carrier protein transacylase |

| fabHA | 8.5 | Also known as yjaX; 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase III A |

| fabHB | 74.1 | Also known as yhfB; 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase III B |

| fabF | 10.9 | Also known as yjaY; 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein synthase II |

| Stress response and drug resistance | ||

| clpC | 13.2 | Negative regulator of late competence genes; positive regulator of autolysin (LytC and LytD) synthesis; class III stress response-related ATPase |

| clpE | 89.4 | ATP-dependent Clp, protease-like |

| ctsR | 15.8 | Negative regulation of class III stress genes |

| groES | 7.0 | Class I heat shock protein (molecular chaperonin) |

| mdr | 13.4 | Resistance to puromycin, nerfloxacin, and tosufloxacin, but not CCCP; multidrug efflux transportera |

| mmr | 22.8 | Methylenomycin A resistance protein |

| Transport | ||

| kapB | 22.4 | Required for activation of KinB in the initiation of sporulation |

| kbl | 23.3 | 2-Amino-3-ketobutyrate coenzyme A ligase (glycine acetyl transferase) |

| licA | 9.2 | Phosphotransferase system lichenan-specific enzyme IIA component |

| licB | 134.5 | Phosphotransferase system lichenan-specific enzyme IIB component |

| licC | 16.9 | Phosphotransferase system lichenan-specific enzyme IIC component |

| rbsA | 11.9 | Ribose ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein)%b |

| rbsB | 24.6 | Ribose ABC transporter (ribose-binding protein) |

| rbsC | 12.8 | Ribose ABC transporter (permease) |

| rbsD | 46.2 | Ribose ABC transporter (membrane protein) |

| rbsK | 22.0 | Ribose metabolism |

| rbsR | 28.6 | Negative regulation of ribose operon (rbsRKDACB); transcriptional regulator (LacI family) |

| Synthesis and other functions | ||

| resC | 8.7 | Essential protein similar to cytochrome c biogenesis protein |

| ribB | 6.9 | Riboflavin synthase (alpha subunit) |

| ribG | 21.9 | Riboflavin biosynthesis |

| ribH | 7.8 | Riboflavin synthase (beta subunit) |

| sigY | 6.8 | RNA polymerase ECF-type sigma factor (sigma-Y) |

| spoIIE | 9.8 | Dephosphorylates SpoIIAA-P and overcomes SpoIIAB-mediated inhibition of sigma-F, required for normal formation of the asymmetric septum (stage II sporulation) |

| tdh | 6.2 | Threonine catabolism |

| Unknown functions | ||

| yabQ | 17.6 | Unknown |

| yacH | 9.0 | Unknown |

| yacI | 19.8 | Unknown |

| ycnC | 7.7 | Unknown, similar to transcriptional regulator (TetR/AcrR family) |

| ycnD | 37.9 | Unknown, similar to NADPH-flavin oxidoreductase |

| ycnE | 40.6 | Unknown |

| ydbH | 6.1 | Unknown, similar to C4-dicarboxylate transport protein |

| ydbM | 6.7 | Unknown, similar to butyryl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase |

| ydeQ | 14.1 | Unknown, similar to NAD(P)H oxidoreductase |

| ydfJ | 17.7 | Unknown, similar to antibiotic transport-associated protein |

| ydgI | 7.7 | Unknown, similar to NADH dehydrogenase |

| ydgJ | 9.3 | Unknown, similar to transcriptional regulator (MarR family) |

| ydiM | 6.1 | Unknown |

| yesE | 6.7 | Unknown |

| yfiE | 495.4 | Unknown |

| yfkO | 10.1 | Unknown, similar to NAD(P)H-flavin oxidoreductase |

| yhcL | 80.7 | Unknown, similar to sodium-glutamate symporter |

| yhgD | 6.9 | Unknown, similar to transcriptional regulator (TetR/AcrR family) |

| yhgE | 9.8 | Unknown, similar to phage infection protein |

| yitA | 6.3 | Unknown, similar to sulfate adenylyltransferase |

| ykcA | 13.4 | Unknown, similar to ABC transporter (binding protein) |

| ykoM | 9.1 | Unknown, similar to transcriptional regulator (MarR family) |

| ykvM | 6.5 | Unknown |

| ylbP | 9.7 | Unknown |

| ylnB | 11.3 | Unknown, similar to sulfate adenylyltransferase |

| ylnC | 59.4 | Unknown, similar to adenylylsulfate kinase |

| ylnD | 682.6 | Unknown, similar to uroporphyrin-III C-methyltransferase |

| ylnE | 8.9 | Unknown |

| ylnF | 43.9 | Unknown, similar to uroporphyrin-III C-methyltransferase |

| ymaA | 5.7 | Unknown, similar to ribonucleoprotein |

| yocJ | 51.6 | Unknown, similar to acyl-carrier protein phosphodiesterase |

| yodC | 7.5 | Unknown, similar to nitroreductase |

| yodS | 35.9 | Unknown, similar to 3-oxoadipate coenzyme A transferase |

| yosP | 8.2 | Unknown, similar to ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase (beta subunit) |

| yozB | 10.5 | Unknown |

| yqjM | 15.6 | Unknown, similar to NADH-dependent flavin oxidoreductase |

| yrhA | 71.7 | Unknown, similar to cysteine synthase |

| yrhB | 17.0 | Unknown, similar to cystathionine gamma-synthase |

| yrkF | 10.1 | Unknown |

| yrkI | 15.8 | Unknown |

| yrrT | 54.1 | Unknown |

| ysbA | 28.6 | Unknown |

| ysxA | 7.6 | Unknown, similar to DNA repair protein |

| yusR | 13.5 | Unknown, similar to 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier protein reductase |

| yvbT | 8.8 | Unknown, similar to alkanal monooxygenase |

| yvgW | 9.8 | Unknown, similar to heavy metal-transporting ATPase |

| yvrD | 32.7 | Unknown, similar to ketoacyl-carrier protein reductase |

| ywgB | 35.8 | Unknown |

| ywjE | 12.4 | Unknown, similar to cardiolipin synthetase |

| ywnA | 66.4 | Unknown |

| ywnB | 2,907.2 | Unknown |

| ywnF | 8.9 | Unknown |

| ywsB | 13.5 | Unknown |

| yxeI | 6.6 | Unknown, similar to penicillin amidase |

| yxeK | 6.9 | Unknown |

| yxeL | 7.6 | Unknown |

| yxeM | 17.3 | Unknown, similar to amino acid ABC transporter (binding protein) |

| yxeN | 15.9 | Unknown, similar to amino acid ABC transporter (permease) |

| yxeO | 6.2 | Unknown, similar to amino acid ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) |

CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone.

ABC, ATP binding cassette.

TABLE 2.

B. subtilis genes repressed by 5 μg of furanone per ml

| Gene | Repression expression ratio | Function |

|---|---|---|

| ackA | −6.3 | Acetate kinase |

| ctrA | −9.1 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis |

| hom | −11.1 | Threonine/methionine biosynthesis, homoserine dehydrogenase |

| pyrAB | −7.1 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis, carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (catalytic subunit) |

| pyrD | −6.7 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| pyrDII | −7.7 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (electron transfer subunit) |

| pyrE | −33.3 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis |

| pyrF | −50.0 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis |

| spoIVB | −5.9 | Intercompartmental signaling of pro-sigma-K processing/activation in the mother cell, essential for spore cortex and coat formation (stage IV sporulation) |

| thrB | −7.1 | Threonine biosynthesis |

| yfiY | −6.3 | Unknown, similar to iron(III) dicitrate transport permease |

| yhbF | −8.3 | Unknown |

| yvaX | −11.1 | Unknown |

| ywqE | −5.9 | Unknown, similar to capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| yycA | −6.3 | Unknown |

Since the labeling efficiencies of Cy3 and Cy5 can be different, as reported previously (40), a dye-swapping experiment was performed to eliminate any artificial effect in labeling, as well as to provide an independent means to verify the results for the first chip. The data from the dye-swapping experiments in this study agreed very well, indicating that the two dyes labeled consistently. For example, for the fatty acid biosynthesis gene yjaY (Table 1) (also known as fabF), the original with-furanone/without-furanone ratios for the level of transcription were determined to be 18.1/1.5 and 21.6/1.6 (average transcription induction level, 12.8-fold) with the Cy3-labeled no-furanone sample and the Cy5-label furanone-containing sample, respectively, and 33.5/3.1 and 15.8/2.0 (average transcription level, 9.4-fold) with the Cy3-labeled furanone-containing sample and the Cy5-labeled no-furanone sample, respectively.

Several stress response genes were also induced by furanone (Table 1). The most noticeable among these genes were some class III heat shock genes, including clpP, clpE, ctsR, yacH, yacI, and clpC (30). From the microarray results, it was found that furanone induced five of the genes (clpC, 13.2-fold; clpE, 89.4-fold; ctsR, 15.8-fold; yacH, 9.0-fold; and yacI, 19.8-fold) and up-regulated clpP (3.5-fold, less than the 5-fold cutoff ratio). In addition to their roles in the heat shock response (clpC and clpP mutants grow at 37°C but not at 54°C [21, 22]), class III heat shock genes are also involved in general stress responses (6), and the clpC and clpP gene products interact with two-component systems involved in modulating sporulation, competence, and exocellular enzyme synthesis (20-22). Hence, the induction of class III heat shock genes and the increased sensitivity of the clpC mutant to furanone (see below) suggest that the class III heat shock genes may be necessary for cell survival with furanone and that the furanone may act as a stressor directly or indirectly.

In addition to class III heat shock genes, some other heat shock genes were also up-regulated (the differential expression was less than the 5-fold cutoff ratio); these genes included dnaK (2.8-fold), grpE (3.3-fold), groES (7.0-fold), groEL (4.8-fold), and dnaJ (2.1-fold). Since the RNA was isolated only 15 min after furanone was added, the induction of these genes took place in less than one doubling time (17.4 min for these conditions). The rapid induction of these stress response genes may help refold lightly damaged proteins and degrade seriously damaged proteins, but how these gene products could allow cells to respond to furanone treatment is not clear (23, 30).

Furanone also greatly induced four genes whose products are involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (Table 1): fabD (8.4-fold), fabHA (8.5-fold), fabHB (74-fold), and fabF (11-fold). fabHA and fabF are likely to belong to the same operon (9), which is consistent with their levels of induction by furanone. The fatty acid biosynthesis pathway is necessary for cell viability and is the target of the antibiotics isoniazid, triclosan, and cerulenin (9).

Furanone at a concentration of 5 μg/ml was also found to repress 15 genes more than fivefold (Table 2). The most noticeable among these genes are the pyr genes for pyrimidine biosynthesis, including pyrAB (−7.1-fold), pyrD (−6.7-fold), pyrDII (−7.7-fold), pyrE (−33.3-fold), and pyrF (−50.0-fold). This may have been due to the repression of the regulatory gene pyrR (−2-fold) (data not shown), which encodes a factor that can cause termination of transcription of the pyr operon (15). It is also possible that furanone, which contains a furan ring, binds to PyrR and thus directly leads to premature termination of transcription of the pyr operon mRNA. It should be noted that the divIVA genes that function in initiation of cell division were down-regulated 2.3-fold by 5 μg of furanone per ml, supporting the twofold inhibition of growth seen with furanone. However, these genes were found to be down-regulated only by furanone and were not repressed (so they are not shown in Table 2), because the cutoff ratio was fivefold.

RNA dot blotting confirmed the microarray results.

To validate the gene expression profiles obtained from the microarray hybridizations, total RNA from B. subtilis cells grown with and without 5 μg of furanone per ml was isolated in the same way that RNA was isolated in the microarray experiments, and the expression of four genes (randomly chosen as representative induced and repressed genes) was determined by RNA dot blot analysis. Four genes (clpC, ctsR, groES, and pyrF) were checked, and the expression ratios of all four agreed with the microarray results (Table 3). For example, clpC was induced 13.2-fold in the microarray experiments and was induced 40-fold in the RNA dot blotting experiment.

TABLE 3.

Gene expression confirmed by RNA dot blotting

| Gene | Function | Expression ratio from DNA microarrays | Expression ratio from RNA dot blotting |

|---|---|---|---|

| clpC | Negative regulator of late competence genes, positive regulator of autolysin (LytC and LytD) synthesis, class III stress response-related ATPase | 13.2 | 40 |

| ctsR | Negative regulation of class III stress genes | 15.8 | 40 |

| groES | Class I heat shock protein (molecular chaperonin) | 7.0 | 15 |

| pyrF | Pyrimidine biosynthesis | −50.0 | −20 |

clpC mutant is more sensitive to furanone.

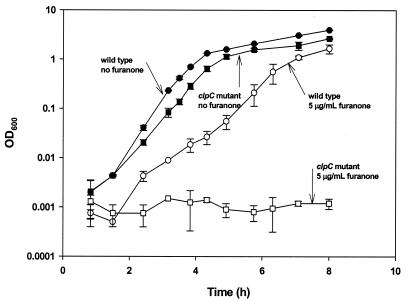

The induction of stress response genes of B. subtilis is reasonable given the inhibitory effect of furanone on gram-positive bacteria. Hence, mutation of a stress response gene may cause the cells to be more sensitive to furanone. To test this hypothesis, wild-type and isogenic clpC B. subtilis strains were grown with different concentrations of furanone (0, 5, 20, and 40 μg/ml), and growth was monitored (Fig. 2). Both the wild type and the clpC mutant grew well without furanone, and the specific growth rate of the clpC mutant was 23% lower than that of the wild type (2.385 ± 0.008 and 1.830 ± 0.001 h−1 for the wild type and the clpC mutant, respectively). In the presence of furanone, however, the growth rate was reduced more significantly for the clpC mutant; 5 μg of furanone per ml decreased the growth rate of the wild-type strain by 43% (to 1.354 ± 0.070 h−1), but no growth was observed after 8 h for the clpC mutant. Higher concentrations of furanone (20 and 40 μg/ml) inhibited growth completely over an 8-h period for both the wild type and the clpC mutant.

FIG. 2.

clpC mutation increases the sensitivity of B. subtilis to furanone.

Furanone is bactericidal for B. subtilis.

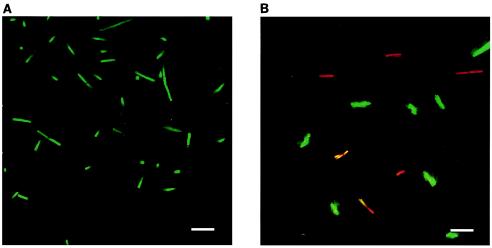

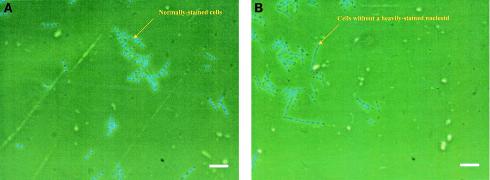

Since furanone at concentrations of 20 and 40 μg/ml completely inhibited the growth of both wild-type B. subtilis 168 and the clpC mutant (B. subtilis QB4756), we investigated whether furanone was bacteriostatic or bactericidal. After treatment with 20 μg of furanone per ml, the viability assay (Fig. 3) indicated that a significant portion of the furanone-treated cells were dead (no dead cells were seen with the sample containing no furanone); hence, this concentration of furanone kills Bacillus cells. Similar results were obtained for B. subtilis JH642 (data not shown). In addition, DAPI staining of untreated cells showed that these cells uniformly had clearly defined nucleoids, while DAPI-stained cells treated with 40 μg/ml showed a diffuse staining pattern and most of the treated cells lacked a clearly defined nucleoid (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

B. subtilis 168 treated with no furanone (A) or with 20 μg of furanone per ml (B) and stained with the LIVE/DEAD viability stain. Live cells are green, and dead cells are red. Scale bars = 10 μm.

FIG. 4.

B. subtilis 168 treated with no furanone (A) or with 40 μg of furanone per ml (B) and stained with DAPI to allow observation of nucleoids. DNA is indicated by blue fluorescence. Scale bars = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Natural furanone inhibits the growth of B. subtilis significantly, as found in this study and previously (25); 5 μg of furanone per ml decreased the growth rate of the wild-type strain by 43%, and 20 μg of furanone per ml inhibited growth completely. In contrast, furanone has no effect on the growth rate of gram-negative bacteria (26), while it inhibits the multicellular behavior of these organisms, including swarming (10, 26), bioluminescence (17), and biofilm formation (12, 26). The mechanism of this inhibition for gram-negative bacteria was delineated with DNA microarrays, which indicated that these phenotypes were the result of interference with both the AI-1 and AI-2 signaling systems. Hentzer et al. (13) found that thesynthetic compound 4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-2(5H)-furanone in P. aeruginosa PAO1 repressed 80% of the genes that were induced by AI-1 quorum sensing, and the natural furanone in the present study repressed 79% of the genes that were induced by AI-2 in Escherichia coli (26a).

Here, the gene expression pattern of B. subtilis was identified by using DNA microarrays, which showed that a sublethal furanone concentration (5 μg/ml) rapidly leads to the induction of specific genes, a significant number of which are related to the stress response (rather than the genes related to signaling, as seen with gram-negative strains). However, general growth genes (such as the divIVA genes discussed above) were not identified as repressed due to the fivefold cutoff ratio for the microarrays and the limited growth inhibition (twofold) caused by the addition of 5 μg of furanone per ml. B. subtilis has four classes of heat shock genes (6), but furanone induced only the class I and III genes (no class II or class IV heat shock genes were induced) at nonbactericidal concentrations. It is also interesting that furanone induced ctsR (15.8-fold), since this gene encodes a negative regulator of class III heat shock genes (6). Since all of the class III heat shock genes were induced by furanone (Table 1), there might be some additional mechanism that controls the expression of these class III heat shock genes.

Besides the induction of the stress response genes noted above and 59 genes with unknown functions, the ribose transport and metabolism genes were also induced by furanone; rbsA (11.9-fold), rbsB (24.6-fold), rbsC (12.8-fold), rbsD (46.2-fold), and rbsK (22.0-fold) were all induced (Table 1). The reason for induction of these genes is not clear. However, the existence of a ribose-like ring in furanone suggests that furanone might have some direct effects on the proteins encoded by these genes. It would be interesting to examine the furanone sensitivity of a strain that can neither transport nor catabolize ribose.

The 9- to 165-fold induction of licABCH is also interesting (Table 1). These four genes form an operon and encode proteins for importing and utilizing oligomeric β-glucosides (compounds which are probably not present in LB medium) as carbon sources. These oligosaccharides are produced by degrading β-1,3-1,4-glucan (lichenan) with the β-1,3-1,4-endoglucanase encoded by licS (29, 35, 36). licS (previously named bglS [35]) was also found to be induced by furanone in the present study (12.9-fold); however, the P value was higher than 0.05 (data not shown).

The extracytoplasmic factor gene sigY was also induced by furanone. However, none of the other 16 sigY-controlled genes (2) was induced by furanone. This might have been because of the short contact time, and more genes might be induced upon longer incubation with furanone. It is also notable that 15 genes with unknown functions, including 5 genes related to pyrimidine biosynthesis, were repressed (Table 2).

Two other sets of gene chip experiments with RNA from cells grown with 5 and 20 μg of furanone per ml were also conducted, but lysozyme rather than the bead beater was used to lyse the cells for RNA isolation (another four microarrays). The results obtained with this RNA were generally similar to the results obtained with bead beater-lysed RNA (there was 80% agreement in the operons that were induced or repressed, indicating the reproducibility of these experiments); however, since the bead beater method lyses cells faster (1 min) than the lysozyme method (5 to 10 min), the RNA quality is expected to be better for the bead beater method, and so this set of data was used for our analysis.

Microscopic analysis indicated that furanone acts as a bactericide at higher concentrations. The red cells seen upon viability staining demonstrated that the furanone treatment (30 min) caused a significant portion of the treated cells to become more permeable, presumably as a result of damage to the plasma membrane. DAPI staining demonstrated that the furanone treatment had a significant effect on the nucleoid distribution in the treated cells. It should be noted that the concentrations of furanone used for microscopy were higher than the concentration used for the microarrays since higher concentrations were required to see changes in the population.

Further study of the furanone-induced genes may help us understand the strategies used by gram-positive bacteria for survival under stress. Also, the furanone-induced genes found in the microarrays are candidates for discovering drugs with activity against gram-positive bacteria.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tarek Msadek (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for sending B. subtilis 168 and B. subtilis QB4756, and we thank James J. Sims of the University of California, Riverside, for providing a furanone standard and for his suggestions on the synthesis process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., B. J. Binder, R. J. Olson, S. W. Chisholm, R. Devereux, and D. A. Stahl. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, K., H. Yamaguchi, C.-M. Kang, K.-I. Yoshida, Y. Fujita, and Y. Sadaie. 2003. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassler, B. L. 1999. How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:582-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beechan, C. M., and J. J. Sims. 1979. The first synthesis of fimbrolides, a novel class of halogenated lactones naturally occurring in the red seaweed Delisea fimbriata (Bonnemaisoniaceae). Tetrahedron Lett. 19:1649-1652. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLisa, M. P., C.-F. Wu, L. Wang, J. J. Valdes, and W. E. Bentley. 2001. DNA microarray-based identification of genes controlled by autoinducer 2-stimulated quorum sensing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5239-5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derre, I., G. Rapoport, and T. Msadek. 1999. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clp and molecular chaperone gene expression in gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 31:117-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edmond, M. B., S. E. Wallace, D. K. McClish, M. A. Pfaller, R. N. Jones, and R. P. Wenzel. 1999. Nosocomial Bloodstream Infections in United States Hospitals: A Three-year Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawcett, P., P. Eichenberger, R. Losick, and P. Youngman. 2000. The transcriptional profile of early to middle sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8063-8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer, H. P., N. A. Brunner, B. Wieland, J. Paquette, L. Macko, K. Ziegelbauer, and C. Freiberg. 2004. Identification of antibiotic stress-inducible promoters: a systematic approach to novel pathway-specific reporter assays for antibacterial drug discovery. Genome Res. 14:90-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gram, L., R. de Nys, R. Maximilien, M. Givskov, P. Steinberg, and S. Kjelleberg. 1996. Inhibitory effects of secondary metabolites from the red alga Delisea pulchra on swarming motility of Proteus mirabilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4284-4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmann, J. D., M. F. W. Wu, P. A. Kobel, F.-J. Gamo, M. Wilson, M. M. Morshedi, M. Navre, and C. Paddon. 2001. Global transcriptional response of Bacillus subtilis to heat shock. J. Bacteriol. 183:7318-7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hentzer, M., K. Riedel, T. B. Rasmussen, A. Heydorn, J. B. Andersen, M. R. Parsek, S. A. Rice, L. Eberl, S. Molin, N. Høiby, S. Kjelleberg, and M. Givskov. 2002. Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria by a halogenated furanone compound. Microbiology 148:87-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hentzer, M., H. Wu, J. B. Andersen, K. Riedel, T. B. Rasmussen, N. Bagge, N. Kumar, M. A. Schembri, Z. Song, P. Kristoffersen, M. Manefield, J. W. Costerton, S. Molin, L. Eberl, P. Steinberg, S. Kjelleberg, N. Høiby, and M. Givskov. 2003. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 22:3803-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjelleberg, S., P. D. Steinberg, and C. Holmstrom. April 1999. Inhibition of gram positive bacteria. International patent WO 99/53915.

- 15.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessières, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manefield, M., R. de Nys, N. Kumar, R. Read, M. Givskov, P. Steinberg, and S. Kjelleberg. 1999. Evidence that halogenated furanones from Delisea pulchra inhibit acylated homoserine lactone (AHL)-mediated gene expression by displacing the AHL signal from its receptor protein. Microbiology 145:283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manefield, M., L. Harris, S. A. Rice, R. de Nys, and S. Kjelleberg. 2000. Inhibition of luminescence and virulence in the black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) pathogen Vibrio harveyi by intercellular signal antagonists. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2079-2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manny, A. J., S. Kjelleberg, N. Kumar, R. de Nys, R. W. Read, and P. Steinberg. 1997. Reinvestigation of the sulfuric acid-catalysed cyclisation of brominated 2-alkyllevulinic acids to 3-alkyl-5-methylene-2(5H)-furanones. Tetrahedron 53:15813-15826. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mascher, T., N. G. Margulis, T. Wang, R. W. Ye, and J. D. Helmann. 2003. Cell wall stress responses in Bacillus subtilis: the regulatory network of the bacitracin stimulon. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1591-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Msadek, T. 1999. When the going gets tough: survival strategies and environmental signaling networks in Bacillus subtilis. Trends Microbiol. 7:201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Msadek, T., V. Dartois, F. Kunst, M.-L. Herbaud, F. Denizot, and G. Rapoport. 1998. ClpP of Bacillus subtilis is required for competence development, motility, degradative enzyme synthesis, growth at high temperature and sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:899-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Msadek, T., F. Kunst, and G. Rapoport. 1994. MecB of Bacillus subtilis, a member of the ClpC ATPase family, is a pleiotropic regulator controlling competence gene expression and growth at high temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5788-5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price, C. W. 2002. General stress response, p. 369-384. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 24.Rasmussen, T. B., M. Manefield, J. B. Andersen, L. Eberl, U. Anthoni, C. Christophersen, P. Steinberg, S. Kjelleberg, and M. Givskov. 2000. How Delisea pulchra furanones affect quorum sensing and swarming motility in Serratia liquefaciens MG1. Microbiology 146:3237-3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren, D., J. J. Sims, and T. K. Wood. 2002. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Bacillus subtilis by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 34:293-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ren, D., J. J. Sims, and T. K. Wood. 2001. Inhibition of biofilm formation and swarming of Escherichia coli by (5Z)-4-bromo-5-(bromomethylene)-3-butyl-2(5H)-furanone. Environ. Microbiol. 3:731-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Ren, D., L. A. Bedzyk, R. W. Ye, S. M. Thomas, and T. K. Wood. Differential gene expression shows natural brominated furanones interfere with the autoinducer-2 bacterial signaling system of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26b.Ren, D., L. A. Bedzyk, P. Setlow, S. M. Thomas, R. W. Ye, and T. K. Wood. 2004. Gene expression in Bacillus subtilis surface biofilms with and without sporulation and the importance of yveR for biofilm maintenance. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86:344-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Schembri, M. A., K. Kjærgaard, and P. Klemm. 2003. Global gene expression in Escherichia coli biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48:253-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnetz, K., J. Stulke, S. Gertz, S. Kruger, M. Krieg, M. Hecker, and B. Rak. 1996. LicT, a Bacillus subtilis transcriptional antiterminator protein of the BglG family. J. Bacteriol. 178:1971-1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumann, W., M. Hecker, and T. Msadek. 2002. Regulation and function of heat-inducible genes in Bacillus subtilis, p. 359-368. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 31.Shoemaker, D. D., and P. S. Linsley. 2002. Recent developments in DNA microarray. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:334-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperandio, V., A. G. Torres, J. A. Giron, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 183:5187-5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanley, N. R., R. A. Britton, A. D. Grossman, and B. A. Lazazzera. 2003. Identification of catabolite repression as a physiological regulator of biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis by use of DNA microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 185:1951-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Surette, M. G., and B. L. Bassler. 1998. Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA 95:7046-7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobisch, S., P. Glaser, S. Krüger, and M. Hecker. 1997. Identification and characterization of a new β-glucoside utilization system in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 179:496-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tobisch, S., J. Stülke, and M. Hecker. 1999. Regulation of the lic operon of Bacillus subtilis and characterization of potential phosphorylation sites of the LicR regulator protein by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 181:4995-5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteley, M., M. G. Bangera, R. E. Bumgarner, M. R. Parsek, G. M. Teitzel, S. Lory, and E. P. Greenberg. 2001. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature 413:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson, M., J. DeRisi, H.-H. Kristensen, P. Imboden, S. Rane, P. O. Brown, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Exploring drug-induced alterations in gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microarray hybridization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12833-12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye, R. W., W. Tao, L. Bedzyk, T. Young, M. Chen, and L. Li. 2000. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 182:4458-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye, R. W., T. Wang, L. Bedzyk, and K. M. Croker. 2001. Application of DNA microarrays in microbial systems. J. Microbiol. Methods 47:257-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng, M., X. Wang, L. J. Templeton, D. R. Smulski, R. A. LaRossa, and G. Storz. 2001. DNA microarray-mediated transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli response to hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 183:4562-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]