Abstract

Two morphological types of appendages, an anchor-like appendage and a peritrichate fibril-type appendage, have been observed on cells of an adhesive bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. strain Tol 5, by use of recently developed electron microscopic techniques. The anchor extends straight to the substratum without branching and tethers the cell body at its end at distances of several hundred nanometers, whereas the peritrichate fibril attaches to the substratum in multiple places, fixing the cell at much shorter distances.

Microbial adhesion is detrimental to both human life and industrial processes, causing infection and contamination by pathogens, dental decay, and biofilm formation, but it can also be beneficial in some environmental bioprocesses and in agriculture (5). Therefore, microbial adhesion has attracted much attention from researchers in various fields (2, 5, 8, 20). Exopolymeric substances (EPS) (10, 11, 14, 17) and proteinaceous appendages such as pili (4, 21) and flagella (3, 9) have been shown to be responsible for tenacious bacterial adhesion by forming a bridge between a cell and a surface. We previously isolated a rod-shaped, gram-negative, toluene-degrading bacterium, strain Tol 5, which was classified as Acinetobacter sp. (genomospecies 10) by 16S rRNA sequence analysis and physiological tests using the Micro Station system (BIOLOG) (13). This strain has a highly hydrophobic cell surface and is highly adhesive to solid surfaces. We have found that this adhesive property is beneficial to a biofiltration process for treating off gas containing volatile organic chemicals such as toluene because it allows the effective immobilization and accumulation of these bacterial cells with their high degradation activity on carrier materials. In the current study, we describe the cell appendages that mediate the adhesion of this bacterium to a solid surface.

Bacterial cell appendages and EPS have been visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Compared with SEM, TEM provides high-resolution images by operating at higher electron-accelerating voltages (usually 70 to 100 kV for biotic samples). Of the several TEM techniques that have been used to observe living specimens (7, 11, 16, 17), negative staining methods produce images that reflect the intact morphology of cell surface structures; such structures are unaffected by sample preparation because, in this method, the sample is mounted on a grid and subjected to electron staining without any other pretreatment. Indeed, many researchers have used TEM coupled with negative staining to visualize bacterial cell surface appendages involved in cell adhesion (9, 12, 15, 21).

To observe the cell surface structure of Tol 5 by TEM, the cells were grown until stationary phase at 28°C in 20 ml of a basal salt medium (Na2HPO4, 4.9 g; KH2PO4, 2.0 g; (NH4)2SO4, 2.0 g; MgCl2 · 6H2O, 340 mg; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 1.7 mg; FeSO4 · 7H2O, 2.4 mg; ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 0.3 mg; CoCl2 · 6H2O, 2.4 mg; MnSO4 · 7H2O, 2.4 mg; CuCl2 · 2H2O, 0.2 mg; Na2MoO4, 0.25 mg [all per liter] [pH 7.2]) supplemented with 10 μl of toluene in a 100-ml Erlenmeyer flask (13). To the flask were added four pieces (1.15 by 1.15 by 1.00 cm) of sponge carrier made of polyurethane, with a specific surface area, density, and porosity of 12 cm2/cm3, 0.115 g/cm3, and 73.8%, respectively. The flask was capped with a rubber stopper and shaken at 115 rpm and 28°C for 42 h. Under these conditions, most of the cells adhered to the polyurethane surface throughout the growth phases. After 42 h, the adhered cells were separated from the polyurethane by vigorous shaking and washed with fresh basal salt medium. Several drops of cell suspension were settled onto a collodion-coated copper grid of mesh size 200 (Nisshin EM) for 5 min. After a brief wash with water, the grid was immersed in 30 μl of filtered 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0) or 5 mg of ruthenium red/ml for 3 min. The grid was removed, and the excess stain was wicked away with filter paper. The grid was then washed with water and dried at room temperature for 45 min. The specimens were observed under an H7500 TEM (Hitachi) operating at 80 kV.

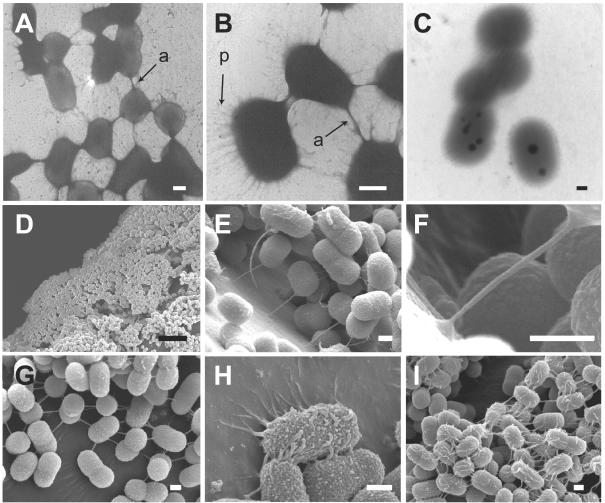

TEM images of the cells stained with phosphotungstic acid revealed the existence of two types of appendages: an anchor extending sparsely but nonpolarly from the cell and a peritrichate fibril (Fig. 1A and B). To clarify the difference between the anchor and the peritrichate fibril, their lengths and diameters were statistically analyzed on enlarged microphotographs. The former were 378 ± 155 (mean ± standard deviation) nm in length and 37 ± 15 nm in diameter (n = 80), while the latter were 286 ± 113 nm in length and 10 ± 3 nm in diameter (n = 111). These differences were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) by a two-tailed Student's t test. We also observed Tol 5 cells stained with ruthenium red, which is used for staining saccharic components on the bacterial cell surface such as lipopolysaccharide, capsule, and extracellular glycoproteins (7, 15, 16). As a result, neither the anchor nor the peritrichate fibril was visible by ruthenium red staining (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, no capsule was detected on Tol 5 cells by ruthenium red staining.

FIG. 1.

Representative images of cell surface appendages on Tol 5 obtained by TEM (A to C) and FE-SEM (D to I). The cells adhered to the polyurethane foam during growth on toluene as the sole carbon source for 42 h. After separation from the polyurethane foam, the cells were mounted on a collodion-coated copper grid and then negatively stained with phosphotungstic acid (A and B) or ruthenium red (C), followed by TEM observation. Anchor-like appendages (a) and peritrichate fibrils (p) can be seen on Tol 5 cells. Stereoscopic images of Tol 5 cells adhering to the polyurethane carrier were obtained by FE-SEM. (D) Tol 5 cells adhere to the substratum in the form of multilayer cell clusters. Both the anchor-like (E to G) and peritrichate fibril-type (H and I) appendages interact with the substratum (E, F, and H) and with other cells (G and I). Bars, 300 nm (A to C and E to I) and 5 μm (D).

TEM is inadequate for directly observing the three-dimensional features of the interaction between the cell and the substratum because TEM can provide only planar projected images or thin-sectioning images. By contrast, SEM has been used to obtain stereoscopic images and to reveal surface features of bacteria, for example, type IV pili of Escherichia coli (4), EPS of Staphylococcus epidermidis (10), and lateral flagella of Vibrio parahaemolyticus (3). Such studies have shown that many fibrils of EPS or pili, extending in random directions from the cell, connect the cell body to the substratum (3, 4, 10). Recently, Kolari et al. showed by using field emission SEM (FE-SEM) for the first time that Deinococcus geothermalis adhered to stainless steel through thin adhesion threads of EPS (14). In comparison to conventional SEM, FE-SEM improves spatial resolution by using a field emission electron source, minimizes sample charge up and damage by operating at lower electron-accelerating voltages, and gives better images of immediate biological surfaces owing to a reduction in electron penetration (19).

For FE-SEM observation, Tol 5 cells were grown under the same conditions as those used for TEM observation. After 42 h of cultivation, the cells adhering to the polyurethane carriers were fixed with 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.067 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 6.5) for 1 h at 4°C and then with 1.3% osmium tetroxide in 0.067 M PBS (pH 6.5) for 2 h at room temperature. After being dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol solutions, the samples were subjected to critical point drying (HCP-2; Hitachi) and then coated with platinum and palladium by using an ion sputter apparatus (E-1030; Hitachi). The specimens were observed under an S4700 FE-SEM (Hitachi) operating at 5 to 10 kV.

FE-SEM revealed that, during growth in the presence of polyurethane, Tol 5 adhered to the substratum of polyurethane in the form of multilayer cell clusters (Fig. 1D). This suggests that the strong adhesive property of Tol 5 is caused by “coadhesion” (5), that is, the subsequent adhesion of cells to the cells that initially adhered to a substratum. Furthermore, both anchors (Fig. 1E to G) and peritrichate fibrils (Fig. 1H and I) were identified on Tol 5 cells by FE-SEM. The cells use the anchor to tether themselves to the substratum like a balloon on a string at distances of several hundred nanometers (Fig. 1E). The anchor extends straight from the cells to the substratum without branching, and its end interacts with the substratum (Fig. 1F). By contrast, the interaction between the peritrichate fibril and the substratum extends along a large part of the appendage (Fig. 1H). The anchor also functions as a long-distance connector between two cells, extending more than 500 nm in many cases (Fig. 1G). It should be noted that only one anchor is involved in each connection between a pair of cells (Fig. 1A, B, and G). By contrast, the peritrichate fibril seems to function in multiples to attain tight cell clusters or aggregates (Fig. 1I).

This is the first report to show fine stereoscopic images of such long-distance interactions between bacterial cells and a substratum mediated by appendages with striking morphology. To our knowledge, such very long, straight, and unbranched appendages like the anchors on Tol 5 cells have not previously been described. In SEM or FE-SEM, however, it is sometimes difficult to rule out the observation of artifacts caused by morphological changes during sample preparation, including dehydration, drying, and metal coating. To overcome this difficulty, environmental SEM (ESEM) and variable pressure SEM (VP-SEM) have been developed. These microscopic techniques permit water-containing specimens to be observed in their natural, or close to natural, state without the need for conventional specimen preparation. However, fine ESEM (or VP-SEM) images of the interaction between bacterial cells and solid surfaces have not been reported, probably because it is difficult to observe a bacterial cell at high pressure (usually, 100 to 600 Pa) with resolution comparable to that achieved under the highly evacuated conditions of conventional SEM (1, 18).

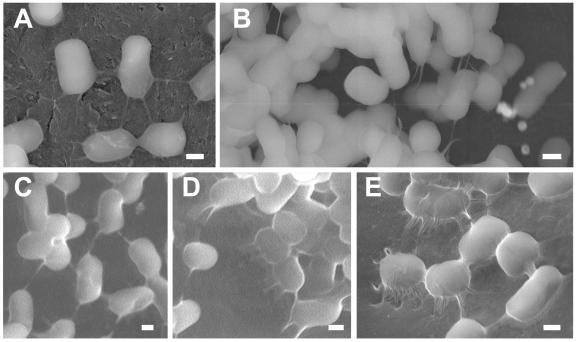

To confirm the unique morphology of the anchor observed by FE-SEM, we used a variable pressure FE-SEM (VP-FESEM) instrument (model S4300 SE/N; Hitachi), which improves VP-SEM by combining it with FE-SEM technology (similar to ESEM-FEG) (6). Tol 5 cells were grown under the same conditions as those used for FE-SEM observation in the presence of polyurethane foam or a carbon specimen stub for 42 h. The cells adhered to the stub or polyurethane foam were fixed with 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.067 M PBS (pH 6.5) for 1 h at 4°C and observed (at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV) without any other pretreatments. Because higher resolution can be obtained by operating VP-FESEM (or ESEM) at a lower pressure, the samples were observed at 80 Pa. We also used a cooling stage unit, which reduces water vaporization and beam damage by keeping the specimens at low temperature (−20°C), to avoid sample shrinkage caused by using a lower pressure than that normally used in ESEM. With this instrumental setup, we obtained fine images of the bacterial cell appendages involved in cell adhesion with a resolution (Fig. 2) higher than that previously reported for ESEM (1, 6, 18). The observation of Tol 5 cells by VP-FESEM confirmed that the intact anchor does indeed have a long, straight morphology. The tethering and cell-to-cell connecting functions of the anchor were confirmed by VP-FESEM (Fig. 2A to D). The peritrichate fibril on Tol 5 cells was also identified by VP-FESEM (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

Representative images of the cell surface morphology of Acinetobacter sp. strain Tol 5 obtained by VP-FESEM. The cells adhered to a carbon specimen stub (A and B) or to polyurethane foam (C to E) during growth on toluene as the sole carbon source for 42 h. (A and C) Pairs of cells are connected by anchor-like appendages. (B and D) The cells also use these anchors to tether themselves to the substratum. (E) The peritrichate fibril-type appendages can also be seen by VP-FESEM. Bars, 300 nm.

In summary, the anchor found on the strongly adhesive bacterium Acinetobacter sp. strain Tol 5 has a striking morphology and directly mediates a long-distance interaction between the cell and the substratum. We are now investigating the adhesion mechanism mediated by these anchor-like and peritrichate fibril-type appendages at the molecular level.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masako Nishimura (Hitachi Science Systems, Ltd.) for technically supporting the observation of bacterial cells by VP-FESEM.

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (A), “Dynamic Control of Strongly Correlated Soft Materials” (no. 413/14045222), from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture, and Technology and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 16360409) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison, D. G., B. Ruiz, C. SanJose, A. Jaspe, and P. Gilbert. 1998. Extracellular products as mediators of the formation and detachment of Pseudomonas fluorescens biofilms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, Y. H., and R. J. Friedman. 1998. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterial surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 43:338-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belas, M. R., and R. R. Colwell. 1982. Scanning electron microscope observation of the swarming phenomenon of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 150:956-959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieber, D., S. W. Ramer, C.-Y. Wu, W. J. Murray, T. Tobe, R. Fernandez, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1998. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 280:2114-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bos, R., H. C. van der Mei, and H. J. Busscher. 1999. Physico-chemistry of initial microbial adhesive interactions—its mechanisms and methods for study. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:179-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callow, J. A., M. P. Osborne, M. E. Callow, F. Baker, and A. M. Donald. 2003. Use of environmental scanning electron microscopy to image the spore adhesive of the marine alga Enteromorpha in its natural hydrated state. Colloids Surface B 27:315-321. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, R., S. D. Acres, and J. W. Costerton. 1984. Morphological examination of cell surface structures of enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli. Can. J. Microbiol. 30:451-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dankert, J., A. H. Hogt, and J. Feijen. 1986. Biomedical polymers: bacterial adhesion, colonization, and infection. Crit. Rev. Biocompat. 2:219-301. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeFlaun, M. F., A. S. Tanzer, A. L. McAteer, B. Marshall, and S. B. Levy. 1990. Development of an adhesion assay and characterization of an adhesion-deficient mutant of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:112-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franson, T. R., N. K. Sheth, H. D. Rose, and P. G. Sohnle. 1984. Scanning electron microscopy of bacteria adherent to intravascular catheters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:500-505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gristina, A. G. 1987. Biomaterial-centered infection: microbial adhesion versus tissue integration. Science 237:1588-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handley, P. S. 1990. Structure, composition and functions of surface structures on oral bacteria. Biofouling 2:239-264. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori, K., S. Yamashita, S. Ishii, M. Kitagawa, Y. Tanji, and H. Unno. 2001. Isolation, characterization and application to off-gas treatment of toluene-degrading bacteria. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 34:1120-1126. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolari, M., U. Schmidt, E. Kuismanen, and M. S. Salkinoja-Salonen. 2002. Firm but slippery attachment of Deinococcus geothermalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:2473-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langille, S. E., and R. M. Weiner. 1998. Spatial and temporal deposition of Hydromonas strain VP-6 capsules involved in biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2906-2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie, E. B., K. N. Brown, J. Lam, and J. W. Costerton. 1979. Morphological stabilization of capsules of group B streptococci, types Ia, Ib, II, and III, with specific antibody. J. Bacteriol. 138:609-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall, K. C., and R. H. Cruickshank. 1973. Cell surface hydrophobicity and the orientation of certain bacteria at interfaces. Arch. Mikrobiol. 91:29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura, M., M. Wada, T. Akiba, and M. Yamada. 2003. Scanning electron microscopy of food-poisoning bacterium Bacillus cereus using variable-pressure SEM. J. Electron Microsc. 52:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pawley, J. 1997. The development of field-emission scanning electron microscopy for imaging biological surfaces. Scanning 19:324-336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quirynen, M., and C. M. L. Bollen. 1995. The influence of surface roughness and surface-free energy on supra- and subgingival plaque formation in man. J. Clin. Periodontol. 22:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg, M., E. A. Bayer, J. Delarea, and E. Rosenberg. 1982. Role of thin fimbriae in adherence and growth of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus RAG-1 on hexadecane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44:929-937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]