Abstract

The secretome obtained from stem cell cultures contains an array of neurotrophic factors and cytokines that might have the potential to treat neurodegenerative conditions. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is one of the most common human late onset and sporadic neurodegenerative disorders. Here, we investigated the therapeutic potential of secretome derived from dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) to reduce cytotoxicity and apoptosis caused by amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide. We determined whether DPSCs can secrete the Aβ-degrading enzyme, neprilysin (NEP), and evaluated the effects of NEP expression in vitro by quantitating Aβ-degrading activity. The results showed that DPSC secretome contains higher concentrations of VEGF, Fractalkine, RANTES, MCP-1, and GM-CSF compared to those of bone marrow and adipose stem cells. Moreover, treatment with DPSC secretome significantly decreased the cytotoxicity of Aβ peptide by increasing cell viability compared to nontreated cells. In addition, DPSC secretome stimulated the endogenous survival factor Bcl-2 and decreased the apoptotic regulator Bax. Furthermore, neprilysin enzyme was detected in DPSC secretome and succeeded in degrading Aβ 1–42 in vitro in 12 hours. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that DPSCs may serve as a promising source for secretome-based treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases that leads to dementia and decline of intellectual function. The pathology of AD is characterized by an accumulation of misfolded proteins, inflammatory changes, and oxidative stresses which result in loss of synaptic contacts and neuronal cell death [1]. It is estimated that the number of AD patients may increase to over 100 million cases by 2050 [2]. Therefore, the identification of new drugs and therapies is urgently needed to either prevent or delay the onset, slow the progression, or improve the symptoms of AD.

One of the main misfolded proteins in AD is amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide. Intensive therapeutic efforts have been attempted to treat AD targeting Aβ, including decreasing its accumulation [3, 4] and inhibiting the inflammatory process caused by it [5]. These therapies intended to delay the onset or slow the progression of AD. Among those potential therapies is the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The therapeutic role of MSCs is based on their restorative and protective features rather than replacement of neuronal cells. Recent studies showed that MSCs can activate microglia [6], induce Aβ clearance, increase autophagy [7], induce neurogenesis [8], and enhance the level of synaptic transmission key proteins in AD models [9]. Additionally, growing stem cells release in culture medium some biologically active substances and structures, such as cytokines, growth factors, enzymes, microvesicles/exosomes, and genetic material [10, 11]. A recent report showed that adipose stem cells (ADSCs) can secrete functional neprilysin bound exosomes [12]. It is known that neprilysin (NEP) is a membrane-bound protease with efficient Aβ degradation activity. The levels of Aβ inversely correlate with the gene dosage of NEP and thus with its enzymatic activity [13]. In theory, the cultured stem cell secretome could be great pharmaceutical/medicinal product. Compared to cells, secretome could be easily biopreserved, sterilized, packaged, and stored. In context, the secretome obtained from mesenchymal stem cell cultures contains an array of neurotrophic factors and cytokines indicating the potential role in treating neurodegenerative conditions [14].

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) are a unique type of mesenchymal stem cells. Besides their neural crest origin, DPSCs express pluripotent stem cell markers such as Oct4, Nanog, Sox, and Klf4 [15], and they have more potent neurogenicity and more immunosuppressive activities than bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) [16]. All these properties actually make them better candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. It has been reported that DPSCs are capable of stimulating long-term regeneration of nerves in the damaged spinal cord [17]. DPSCs promoted the regeneration of transected axons in a severed rat spinal cord by preventing multiple axon growth inhibitors and by preventing the apoptosis of neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [18]. Moreover, DPSCs attenuated Aβ 1–42 toxicity and increased the neuronal viability when cocultured with primary hippocampal neurons suggesting a neurotrophic effect [19].

To our knowledge, the therapeutic potential of DPSC secretome for AD has not been evaluated. In the present study, we characterized the DPSC secretome and investigated its neuroprotective effects against amyloid beta (Aβ) induced neurotoxicity in vitro. We examined the levels of anti- and proapoptotic factors, Bcl-2 and Bax, respectively, to investigate the role of DPSC secretome against Aβ induced apoptosis. Bcl-2 is one of the most important antiapoptotic factors that have a major role in stimulating the survival of cells while Bax is a proapoptotic factor that induces apoptosis and cell death. We also checked whether DPSCs can secrete the Aβ-degrading enzyme, neprilysin (NEP), and the effects of DPSC secretome in vitro by quantifying Aβ-degrading activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Isolation and Culture of Dental Pulp Stem Cells

Normal human third molar teeth indicated for extraction were collected from patients aged 20–28 years at the Aichi-Gakuin University Dental Hospital, in accordance with the approved guidelines set by the School of Dentistry, Aichi-Gakuin University, and the National Centre for Geriatrics and Gerontology Research Institute. All experimental protocols were approved by the National Centre for Geriatrics and Gerontology Research Institute. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this experiment and donor information for used dental pulp derived mesenchymal stem cells can be found in Supplementary Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/8102478. The pulp was gently removed using a sterile dental probe and the collected pulp tissue was dissected and digested in 0.2% Liberase MNP-S enzyme (Roche, Germany). The isolated dental pulp cells were cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% human serum and Antibiotic-Antimitotic solution (Gibco, Life Technologies) containing 500 units/mL of penicillin, 500 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 1.25 μg/mL of Fungizone®. Cells were selected on the basis of their ability to adhere to the dish; nonadherent cells were removed during medium replacement after 4-5 days in culture. Subsequent experiments have been performed in triplets on 3 different samples.

2.2. Preparation and Characterization of DPSC Secretome Using MAGPIX Cytokine Multiplex

For preparation of DPSC, BMSC, and ADSC secretomes (donor information for used bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells can be found in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3), cells at passages (4th-5th) were grown to 60% confluency; then culture medium was switched to DMEM without serum and cells were starved for 24 hours. The medium was then collected and concentrated approximately 40-fold by Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit with an ultracel-3 membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, USA) was added to the collected secretome at a concentration of 10 μL/mL. Protein concentration was measured by Coomassie (Bradford) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). The collected secretome was either used immediately or frozen at −30°C up to one month. Content analysis of DPSC secretome against BMSC and ADSC secretomes for cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors was performed using commercially available MAGPIX cytokine human 41 multiplex (Millipore) according to manufacturer's instructions. All data were compensated to pg/mL/106 cells.

2.3. Preparation of Aβ 1–42 Peptide

Aβ 1–42 (Peptide Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan) was provided as an amorphous powder that has been lyophilized from dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution. 1 mM solution was prepared by dissolving Aβ 1–42 powder thoroughly in DMSO according to the manufacturer's instructions. The dissolved Aβ 1–42 was used immediately after preparation.

2.4. SH-SY5Y Cells Viability Analysis and Morphological Assessment

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (Sanyo Chemical Industries, Ltd.) were cultured in DMEM/ham F12 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS and Antibiotic-Antimitotic solution (Gibco, Life Technologies). In order to decide concentration and incubation time, SH-SY5Y cells were grown in 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with Aβ 1–42 (Peptide Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan) over a range of concentrations (0 [control], 2, 5, or 10 μM) for variable incubation times (0, 12, and 24 hours). The extent of cell growth and cell viability was assessed using a cell counting kit 8 assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) at 0, 12, and 24 h. Before assessment, the cells were washed and then 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance at 450 nm was determined by a multiplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Appliskan Multimode). Mean values of the mean absorbance rates from four wells were calculated. The neuroprotective effect of DPSC secretome was then tested in SH-SY5Y cells treated with 5 μM of Aβ. SH-SY5Y cells were cultured for 24 hours; then the cells were divided into three groups exposed to either (i) 5 μM of Aβ 1–42, (ii) Aβ 1–42 in combination with DPSC secretome (5 μg/mL), or (iii) nonexposed cells as negative control. Cells were incubated for 24 hours in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. SH-SY5Y cells were then collected for assay. The viability of cells was assessed as previously described and morphological changes were observed under an inverted light microscope (Leica, 6000B-4) using Suite V3 (Leica).

2.5. Antiapoptotic Effect of DPSC Secretome

Cells were harvested from the three experimental groups and homogenized in 1X sample SDS lysis buffer. The protein concentration of cell lysates was determined by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Ten micrograms of total protein was separated by electrophoresis in TGX™ acrylamide gel (Bio-Rad) under reducing conditions and then electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (immobilon-p, Millipore, USA). After protein transfer, the membranes were treated with 5% skim milk as a blocking buffer. The membranes were then probed with antibodies against either Bax (mouse, 610982, 1.5 : 1000, BD Transduction Laboratories, USA), Bcl-2 (mouse, 610538, 1.5 : 1000, BD Transduction Laboratories, USA), or β-actin (rabbit, RB-9421, 1 : 1000, Thermo Scientific, UK). Proteins of interest were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 1000, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and visualized with Luminata Forte Western HRP blotting substrate (Millipore, Germany) according to the provided protocol using light capture II cooled CCD camera system (ATTO cooperation, Japan). Detected bands were analyzed using Image J software (version 1.49r15).

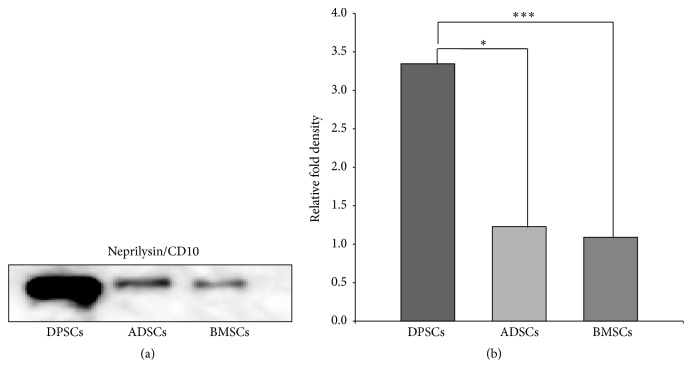

2.6. Detection of Neprilysin/CD10 in DPSC Secretome

The protein level of neprilysin/CD10 in DPSC secretome was investigated and compared to its level in BMSC and ADSC secretomes using western blot analysis. After measuring the total protein concentration of secretomes using Coomassie (Bradford) protein assay, five micrograms of total protein was separated by electrophoresis under reducing conditions. PVDF membranes were incubated after blotting and blocking with primary antibody against neprilysin/CD10 (mouse, ab951, 1 : 1000, Abcam, USA). The membranes were visualized after secondary antibody treatment to detect and compare protein signals. Detected bands were analyzed using Image J software (version 1.49r15).

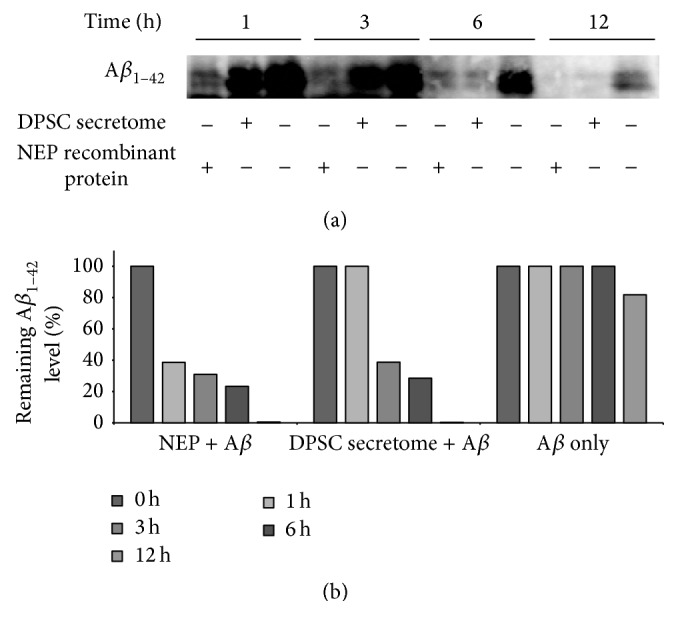

2.7. Degradation Ability of DPSC Secretome for Aβ 1–42

Samples of 5 μM Aβ 1–42 were incubated at 37°C either with DPSC secretome (5 μg/mL) or neprilysin/CD10 recombinant protein or alone for increasing length time (1, 3, 6, and 12 hours). At each time point, samples were collected and analyzed for remaining Aβ by western blot analysis using a primary antibody against Aβ (mouse, 10323, 1 : 1000, IBL, Japan).

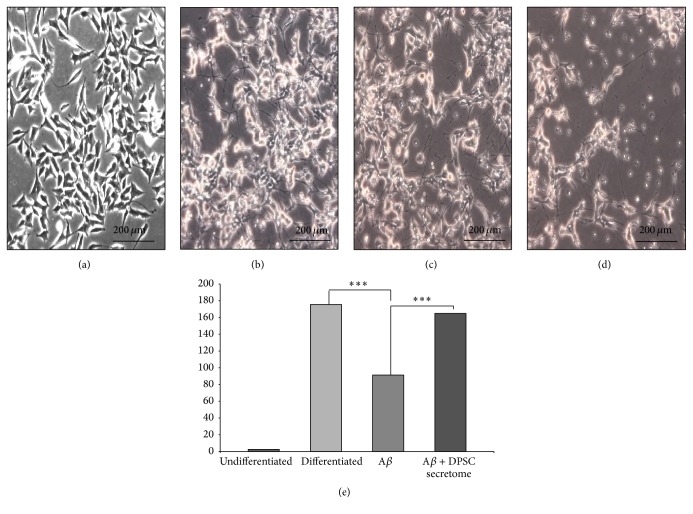

2.8. Neuroprotective Ability of DPSC Secretome

SH-SY5Y cells were cultured for 10 days in serum-free DMEM-F12 to induce neurogenic differentiation. Cells were then divided into 3 groups: cells either exposed to Aβ 1–42 only or Aβ 1–42 and DPSC secretome or nonexposed cells. Undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells were used as negative controls. Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator for 24 hours. Successful differentiation was confirmed using neuronal differentiation markers: neurofilament and neuromodulin (Supplementary Figure S6). Morphology and neurite lengths were then assessed. For neurite lengths assessment, multiple representative fields of cells morphology were photographed with an inverted light microscope (Leica, 6000B-4). Captured images were labeled with a scale according to the correspondent microscope magnification (×10). The images scale was used to convert pixels units into micrometers (μm), using Image J software (version 1.49r15). The length of 5 to 10 neurites per field was traced and measured.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard error. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft (MS) Office Excel Software. One-way ANOVA was used to assess for differences between groups and p values were calculated using unpaired Student's t-test using IBM SPSS version 19. Differences were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05. The number of replicates in each experiment is indicated in the figure legends.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of DPSC Secretome

DPSCs were successfully isolated from human third molar teeth indicated for extraction; their secretome was collected, analyzed, and compared to BMSC and ADSC secretomes using MAGPIX cytokine multiplex (Millipore). Various growth factors and cytokines were investigated as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of cytokines and growth factors investigated by MAGPIX cytokine multiplex.

| Name of cytokine/growth factor | Abbreviation/another name |

|---|---|

| Endothelial growth factor | EGF |

| Fibroblast growth factor-2 | FGF-2 |

| Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 | FLT-3L |

| FRACTALKINE | CX3CL1 |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor | GM-CSF |

| Human platelet-derived growth factor BB | PDGF-BB |

| Interferon alpha 2 and gamma | INFα2, INFγ |

| Interleukin-12 p40 | IL-12p40 |

| Interleukin-12 p70 | IL-12p70 |

| Interleukin-13 | IL-13 |

| Interleukin-15 | IL-15 |

| Interleukin-17 | IL-17 |

| Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist | IL-1ra |

| Interleukin-1 alpha and beta | IL-1α, IL-1β |

| Interleukin (2–10) | IL-(2–10) |

| Macrophage-derived chemokine | MDC |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha and beta | MIP-1α, MIP-1β |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 and 3 | MCP-1, MCP-3 |

| Platelet-derived growth factor-AA | PDGF-AA |

| RANTES | CCL5 |

| CXCL10 | IP-10 |

| Soluble CD40 ligand | sCD40L |

| Tumor necrosis factor alpha and beta | TNFα, TNFβ |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor | VEGF |

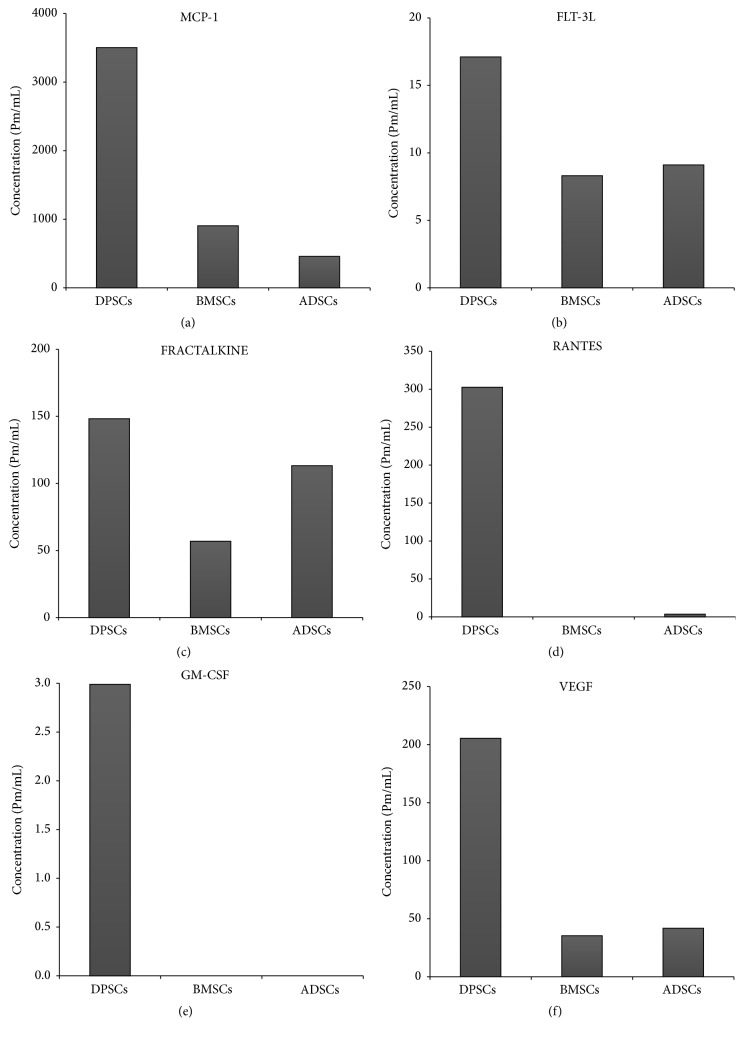

Analysis showed that DPSC secretome contains higher concentrations of VEGF, RANTES, FRACTALKINE, FLT-3, GM-CSF, and MCP-1 than both BMSC and ADSC secretomes (Figure 1). Those factors and cytokines play important roles when it comes to neurodegenerative diseases. Some of these factors have neuroprotective effects like RANTES and VEGF [20, 21], while others may have antiapoptotic effects as MCP-1 [22] and FRACTALKINE [23]. FLT-3 can regulate microglial activation [24] and G-MCSF reverse cognitive impairment and amyloidosis [25]. These results indicate that DPSCs might have better therapeutic potentials for neurodegenerative diseases than other MSCs in terms of secreted neurotrophic factors.

Figure 1.

DPSCs secrete some cytokines and growth factors more than both BMSCs and ADSCs. (a) MCP-1. (b) FLT-3L. (c) FRACTALKIN. (d) RANTES. (e) GM-CSF. (f) VEGF.

3.2. Exposure to Aβ Reduces Cell Viability of SH-SY5Y Cells in a Dose- and Time-Dependent Manner

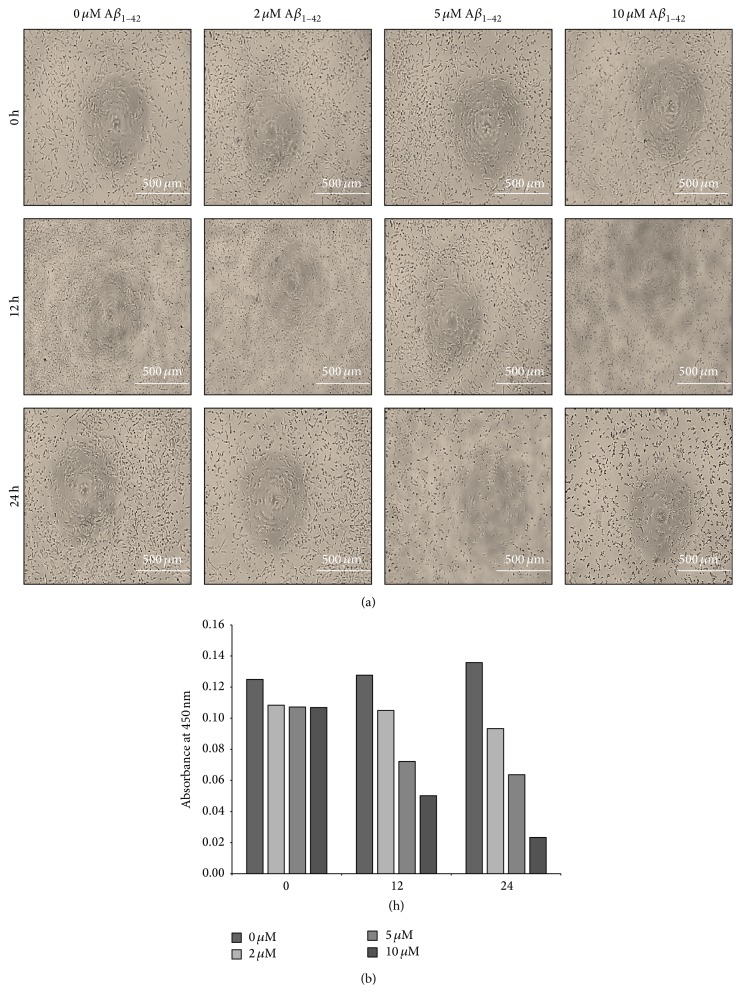

In order to determine the concentration and incubation time, neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were treated with varying concentrations (0 [control], 2, 5, or 10 μM) of Aβ 1–42 (Peptide Institute, Inc., Osaka, Japan) for variable incubation times (0, 12, and 24 hours). Aβ 1–42 treatment resulted in cellular morphological changes and loss of cellular viability in dose- and time-dependent manner (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). The effect of Aβ 1–42 on the viability of SH-SY5Y cells was most obvious after 24 hours and at 5 μM concentration as the cytotoxic effect of Aβ 1–42 was observed clearly without losing all cells. Thus, treatment with 5 μM concentration of Aβ 1–42 for 24 hours was chosen for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Exposure to Aβ 1–42 decreased the viability of SH-SY5Y cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. (a) Phase contrast micrographs of SH-SY5Y cells treated with various concentrations of Aβ 1–42 for different periods of time. (b) Cell viability as detected at 450 nm absorbance (mean ± SE).

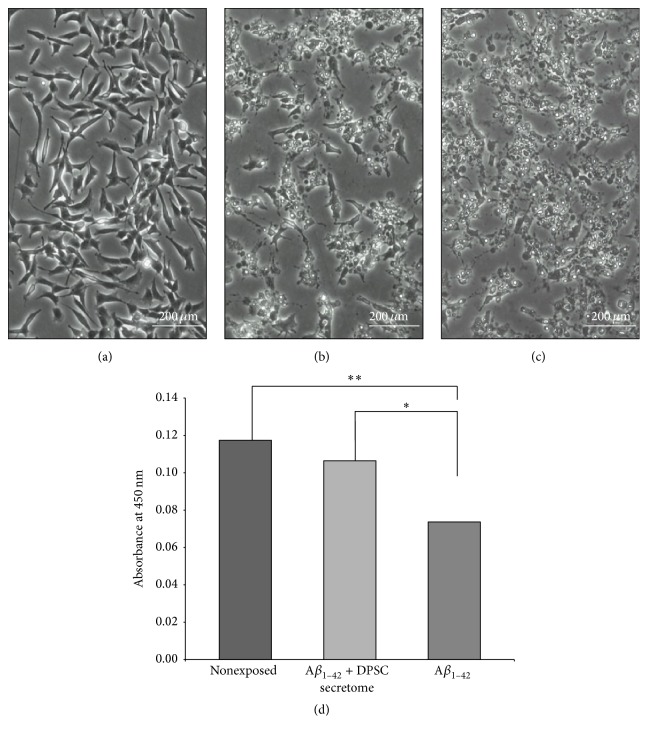

3.3. DPSC Secretome Treatment Preserves Morphology and Improves the Viability of SH-SY5Y Cells

SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 5 μM Aβ 1–42 and treated with DPSC secretome (5 μg/mL) were compared to nontreated cells for morphological changes. Cells treated with DPSC secretome appeared to preserve their intact morphological shape while obvious morphological changes have been noticed in nontreated cells (Figures 3(a), 3(b), and 3(c)). Moreover, there was a significant increased viability (p = 0.0103) in cells treated with DPSC secretome as total cell number was higher compared to nontreated cells (0.11 ± 0.008 and 0.07 ± 0.005, resp., n = 3, mean ± SE) (Figure 3(d)).

Figure 3.

DPSC secretome treatment preserves morphology and improves the viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ 1–42. (a–c) Phase contrast micrographs of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ 1–42 only, Aβ 1–42, and DPSC secretome or nonexposed as control (full-size images are presented in Supplementary Figure S1). (d) Cell viability as detected at 450 nm absorbance (mean ± SE, n = 3. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01).

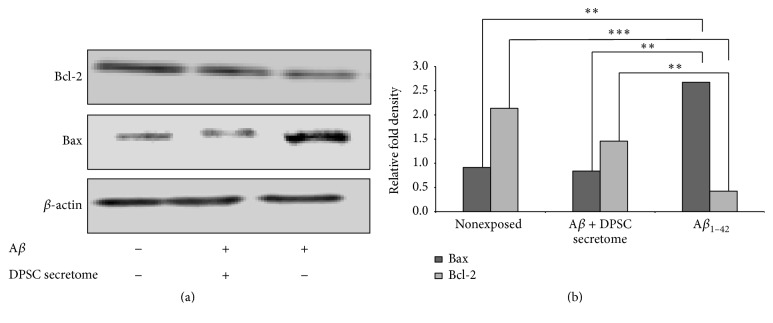

3.4. Antiapoptotic Effects of DPSC Secretome

SH-SY5Y cells were divided into three groups: cells either exposed to (i) 5 μM of Aβ 1–42 alone or (ii) Aβ 1–42 in combination with DPSC secretome (5 μg/mL) or (iii) Nonexposed cells as negative control. Cells lysates from the three groups were analyzed by western blotting to detect expression of Bcl2 (antiapoptotic factor) and Bax (apoptotic regulator). DPSC secretome treated cells showed a significant increase in Bcl2 expression (p = 0.000) compared to the nontreated cells (1.46 ± 0.025 and 0.42 ± 0.06, resp., n = 3, mean ± SE). On the other hand, Bax expression was significantly decreased (p = 0.001, 0.84 ± 0.03 and 2.6741 ± 0.18, n = 3, mean ± SE) (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)). These results indicate that DPSC secretome has an antiapoptotic effect by stimulating the endogenous survival factor Bcl-2 and decreasing the apoptotic regulator Bax, revealing the possible mechanism of neuroprotection.

Figure 4.

DPSC secretome stimulates the endogenous survival factor Bcl-2 and decreases the apoptotic regulator Bax. (a) Immunoblotting analysis with an anti-Bax, an anti-Bcl2, or an anti-actin antibody (full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure S2). (b) Relative fold density as analyzed by Image J (mean ± SE, n = 3. ∗∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001).

3.5. Neprilysin (NEP) Content in DPSC Secretome and Its Degrading Ability

NEP expression was significantly increased in DPSC secretome compared to that in both BMSC (p = 0.000) and ADSC (p = 0.01) secretomes (3.35 ± 0.073, 1.23 ± 0.16, and 1.09 ± 0.28, resp., n = 3, mean ± SE), indicating the stronger potential of DPSCs to degrade Aβ 1–42 protein (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)). We sought to determine whether DPSC secretome could proteolytically degrade Aβ 1–42 in vitro. Quantitative immunoblotting analysis showed that incubation with 5 μg/mL of DPSC secretome resulted in complete degradation of 5 μM of Aβ 1–42 after 12 hours (Figure 6). However, the rate of Aβ 1–42 hydrolysis was relatively slow at the first 3 hours when compared to hydrolysis by NEP recombinant protein.

Figure 5.

DPSC secretome contains a higher concentration of neprilysin/CD10. (a) Immunoblotting analysis with an anti-NEP antibody (full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure S3). (b) Relative fold density as analyzed by Image J (mean ± SE, n = 3. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

DPSC secretome degrades Aβ 1–42 protein in vitro. (a) Immunoblotting analysis at each time point with an anti-Aβ antibody (full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Figure S4). (b) Quantitation of remaining Aβ 1–42 level (mean ± SE).

3.6. Neuroprotective Ability of DPSC Secretome

Neurodifferentiated SH-SY5Y exposed to Aβ 1–42 and treated with DPSC secretome kept their morphology and viability compared to nontreated cells. Cells not treated with DPSCs secretome showed decreased viability (Figures 7(a)–7(d)) and significant shrinkage in neural extensions compared to treated cells (165 ± 3.2 and 91 ± 3.6, resp., n = 3, p = 0.000, mean ± SE) (Figure 7(c)), indicating the neuroprotective ability of the DPSC secretome against Aβ 1–42 induced neurotoxicity.

Figure 7.

DPSC secretome has neuroprotective ability against Aβ 1–42 induced neurotoxicity. (a–d) Representative photos demonstrating the morphology of SH-SY5Y cells in different treatment groups: undifferentiated, nonexposed differentiated, differentiated exposed to Aβ 1–42 and DPSC secretome, and differentiated exposed to Aβ 1–42 only (full-size images are presented in Supplementary Figure S5) (e). Quantitative analysis of SH-SY5Y neurite outgrowth after exposure to Aβ 1–42 for 24 hours (mean ± SE, n = 3, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Recent studies on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have provided promising new ways for tissue repair in central nervous system diseases [26]. Initially, it was considered that the true therapeutic potential of MSCs depends mainly on their ability to differentiate into multiple lineages, but recently it has been shown that their therapeutic potential was mostly related to the growth factors that they secrete rather than to their differentiation potential [27]. In the present study, we evaluated the therapeutic potential of DPSC secretome for AD treatment. Our results demonstrated that DPSC secretome was able to reduce the toxic effect of Aβ 1–42 on neuroblastoma cells, secrete Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin, and decrease Aβ 1–42 induced apoptosis. To our knowledge, this is the first report to investigate the therapeutic potentials of DPSC secretome for Alzheimer's disease.

During the organogenesis of the tooth, dental stem cells play critical roles by secreting neurotrophic factors such as NGF (nerve growth factor), GDNF (glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor), and BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) which results in innervation of dental tissues [28]. This neurotrophic feature brings an important advantage to dental stem cells in terms of restoration of neuronal tissues. In our study, we started by characterizing the secretome collected from DPSCs in an attempt to know its content and compare it to other MSC secretomes. We have identified that DPSCs secrete (in addition to the previously mentioned factors) other important growth factors and cytokines which might be involved in attenuation of neurotoxicity such as VEGF, RANTES, FRACTALKINE, FLT-3, and MCP-1. Furthermore, DPSCs were found to secrete these cytokines and factors at higher concentrations than both ADSCs and BMSCs. While VEGF secretion enhances angiogenesis during tissue repair [22], RANTES was found to increase neuronal cell survival and to have a neuroprotective effect [20], and FRACTALKINE is considered as a key microglial pathway in protecting against AD-related cognitive deficits [23]. Moreover, FLT-3 is involved in microglial cells' capacity to respond to environmental cues to function as antigen presenting cells and mediate CNS inflammation, suggesting that FLT-3 may be a therapeutic target on microglia to alleviate CNS inflammation [24]. Furthermore, G-MCSF can reverse cognitive impairment and amyloid pathology in AD mice [25]. Taken together, the data presented indicate that DPSC secretome has high therapeutic potentials in neurodegenerative diseases.

We evaluated the ability of the DPSC secretome to protect neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) against Aβ 1–42 induced toxicity. The exposure of the SH-SY5Y cultures to Aβ led to a reproducible and dose-time-dependent loss in cell viability. This toxic effect was attenuated when the cells were cotreated with DPSC secretome. It has been previously demonstrated that coculturing with DPSCs significantly reduced Aβ 1–42 induced toxicity in primary cultures of mesencephalic and hippocampal neurons and led to an increase in neuronal viability [19]. This can now be attributed to the factors that DPSCs secrete in culture.

Several approaches have been made to investigate the potential role of Aβ in the apoptotic mechanism of AD. Initial studies suggested that Aβ plaques directly induce apoptosis in vitro [29]. However, it was suggested that Aβ is more likely to induce apoptosis indirectly, possibly by first promoting oxidative stress through the production of reactive oxidative species (ROS) [30]. Aβ also activates apoptosis pathway by upregulating the proapoptotic Bax protein and inducing other apoptotic signal cascades [31]. In the present study, we showed that DPSC secretome upregulated Bcl-2 and downregulated Bax expression in SH-SY5Y cells counteracting the effect of Aβ. Bax and caspase-3 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD and are components of a well-defined molecular pathway of neuronal apoptosis [32]. And given that Bcl-2 inhibits Bax-induced apoptosis, delays caspase expression, and increases neuron survival [33], it will be expected that manipulating the expression and or the activity of Bcl-2 will increase neuronal survival. Growth factors and cytokines like FGF2 [34], VEGF [35], RANTES [36], and Fractalkine [37] can upregulate Bcl-2 expression. And the data presented here proves that those factors not only are found abundantly within the DPSC secretome but also are found at higher concentrations than in other MSC secretomes. Accordingly, DPSC secretome exhibits those antiapoptotic properties.

Recently, there has been considerable debate over the enzyme or enzymes that contribute most to Aβ degradation in human brain. It is likely that multiple proteases, both intracellular and extracellular, may play a role in determining Aβ concentration in human brain. Neprilysin (NEP) is one of the major proteases involved in that debate. NEP is a membrane-bound protease with efficient Aβ degradation activity. It has been found that levels and activity of NEP are decreased in AD brains, suggesting that a reduction in Aβ degradation may contribute to the development of the disease [38]. When it comes to NEP and MSCs, a study showed that the coculture of human MSCs and mouse microglia increased neprilysin expression under the exposure of Aβ [39]. It has been also reported that adipose stem cells (ADSCs) can secrete functional neprilysin bound exosomes [12]. In our study, we investigated the expression of neprilysin within the DPSC secretome at a protein level using western blot analysis. Our results showed that DPSC secretome contains functional NEP that was able to degrade 5 μM of Aβ 1–42 in vitro within 12 hours. Another important observation was that DPSCs expressed NEP at a higher level than both BMSCs and ADSCs. These results suggest that DPSC secretome has the capacity to contribute to clearance of Aβ accumulated in the brain, indicating that DPSCs may serve as a promising source for secretome-based AD treatment.

In conclusion, the results of the present study support the use of DPSCs as a source of secretome which is highly enriched in neurotrophic factors, Aβ-degrading enzyme (NEP), and antiapoptotic factors, rendering DPSCs promising candidates for secretome-based therapy for AD providing a novel therapeutic approach against one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Donor information for used dental pulp derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Table 2: Donor information for used bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Table 3: Donor information for used Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Figure 1: DPSC secretome treatment preserves morphology and improves viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ1–42.

Supplementary Figure 2: DPSC secretome stimulates the endogenous survival factor Bcl-2 and decreases the apoptotic regulator Bax.

Supplementary Figure 3: DPSC secretome contains higher concentration of Neprilysin/CD10.

Supplementary Figure 4: DPSC secretome degrade Aβ1–42 protein in vitro.

Supplementary Figure 5: DPSC secretome has neuroprotective ability against Aβ1–42 induced neurotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nobuyuki Kimura for his guidance throughout writing this paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Authors' Contributions

Misako Nakashima supervised the project, designed the study, and reviewed the paper. Nermeen El-Moataz Bellah Ahmed participated in the design of the study, carried out the experiments, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the paper. Masashi Murakami participated in the western blotting analysis. Yujiro Hirose performed the cytokine/chemokine analysis. All authors read and approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Li M., Guo K., Ikehara S. Stem cell treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(10):19226–19238. doi: 10.3390/ijms151019226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(2):208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carret-Rebillat A.-S., Pace C., Gourmaud S., et al. Neuroinflammation and Aβ accumulation linked to systemic inflammation are decreased by genetic PKR down-regulation. Scientific Reports. 2015;5, article 8489 doi: 10.1038/srep08489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piermartiri T. C. B., Figueiredo C. P., Rial D., et al. Atorvastatin prevents hippocampal cell death, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress following amyloid-β 1 − 40 administration in mice: evidence for dissociation between cognitive deficits and neuronal damage. Experimental Neurology. 2010;226(2):274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W.-W., Lu S., Su Y.-J., et al. Decreasing oxidative stress and neuroinflammation with a multifunctional peptide rescues memory deficits in mice with Alzheimer disease. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2014;74:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma T., Gong K., Ao Q., et al. Intracerebral transplantation of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alternatively activates microglia and ameliorates neuropathological deficits in Alzheimer's disease mice. Cell Transplantation. 2013;22(1):S113–S126. doi: 10.3727/096368913X672181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin J. Y., Park H. J., Kim H. N., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance autophagy and increase β-amyloid clearance in Alzheimer disease models. Autophagy. 2014;10(1):32–44. doi: 10.4161/auto.26508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Y., Ma T., Gong K., Ao Q., Zhang X., Gong Y. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation promotes adult neurogenesis in the brains of Alzheimer's disease mice. Neural Regeneration Research. 2014;9(8):798–805. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.131596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae J.-S., Jin H. K., Lee J. K., Richardson J. C., Carter J. E. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells contribute to the reduction of amyloid-β deposits and the improvement of synaptic transmission in a mouse model of pre-dementia Alzheimer's disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2013;10(5):524–531. doi: 10.2174/15672050113109990027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crigler L., Robey R. C., Asawachaicharn A., Gaupp D., Phinney D. G. Human mesenchymal stem cell subpopulations express a variety of neuro-regulatory molecules and promote neuronal cell survival and neuritogenesis. Experimental Neurology. 2006;198(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biancone L., Bruno S., Deregibus M. C., Tetta C., Camussi G. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2012;27(8):3037–3042. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsuda T., Tsuchiya R., Kosaka N., et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells secrete functional neprilysin-bound exosomes. Scientific Reports. 2013;3, article 1197 doi: 10.1038/srep01197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul G., Anisimov S. V. The secretome of mesenchymal stem cells: potential implications for neuroregeneration. Biochimie. 2013;95(12):2246–2256. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karaöz E., Demircan P. C., Saflam Ö., Aksoy A., Kaymaz F., Duruksu G. Human dental pulp stem cells demonstrate better neural and epithelial stem cell properties than bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2011;136(4):455–473. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0858-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerkis I., Kerkis A., Dozortsev D., et al. Isolation and characterization of a population of immature dental pulp stem cells expressing OCT-4 and other embryonic stem cell markers. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;184(3-4):105–116. doi: 10.1159/000099617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mead B., Logan A., Berry M., Leadbeater W., Scheven B. A. Paracrine-mediated neuroprotection and neuritogenesis of axotomised retinal ganglion cells by human dental pulp stem cells: comparison with human bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109305.e109305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai K., Yamamoto A., Matsubara K., et al. Human dental pulp-derived stem cells promote locomotor recovery after complete transection of the rat spinal cord by multiple neuro-regenerative mechanisms. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(1):80–90. doi: 10.1172/jci59251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Almeida F. M., Marques S. A., Ramalho B. D. S., et al. Human dental pulp cells: a new source of cell therapy in a mouse model of compressive spinal cord injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2011;28(9):1939–1949. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Apel C., Forlenza O. V., De Paula V. J. R., et al. The neuroprotective effect of dental pulp cells in models of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2009;116(1):71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tripathy D., Thirumangalakudi L., Grammas P. RANTES upregulation in the Alzheimer's disease brain: a possible neuroprotective role. Neurobiology of Aging. 2010;31(1):8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Religa P., Cao R., Religa D., et al. VEGF significantly restores impaired memory behavior in Alzheimer's mice by improvement of vascular survival. Scientific Reports. 2013;3, article 2053 doi: 10.1038/srep02053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semple B. D., Bye N., Rancan M., Ziebell J. M., Morganti-Kossmann M. C. Role of CCL2 (MCP-1) in traumatic brain injury (TBI): evidence from severe TBI patients and CCL2−/− mice. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2010;30(4):769–782. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho S.-H., Sun B., Zhou Y., et al. CX3CR1 protein signaling modulates microglial activation and protects against plaque-independent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(37):32713–32722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeBoy C. A., Rus H., Tegla C., et al. FLT-3 expression and function on microglia in multiple sclerosis. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2010;89(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyd T. D., Bennett S. P., Mori T., et al. GM-CSF upregulated in rheumatoid arthritis reverses cognitive impairment and amyloidosis in Alzheimer mice. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;21(2):507–518. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uccelli A., Laroni A., Freedman M. S. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases. The Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(7):649–656. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teixeira F. G., Carvalho M. M., Neves-Carvalho A., et al. Secretome of mesenchymal progenitors from the umbilical cord acts as modulator of neural/glial proliferation and differentiation. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2015;11(2):288–297. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9576-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nosrat I. V., Smith C. A., Mullally P., Olson L., Nosrat C. A. Dental pulp cells provide neurotrophic support for dopaminergic neurons and differentiate into neurons in vitro; implications for tissue engineering and repair in the nervous system. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19(9):2388–2398. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yankner B. A. Mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1996;16(5):921–932. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattson M. P. Neuronal life-and-death signaling, apoptosis, and neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2006;8(11-12):1997–2006. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradis E., Douillard H., Koutroumanis M., Goodyer C., LeBlanc A. Amyloid beta peptide of Alzheimer's disease downregulates Bcl-2 and upregulates Bax expression in human neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(23):7533–7539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07533.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattson M. P. Apoptosis in neurodegenerative disorders. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2000;1(2):120–129. doi: 10.1038/35040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pérez-Navarro E., Gavaldà N., Gratacòs E., Alberch J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents changes in Bcl-2 family members and caspase-3 activation induced by excitotoxicity in the striatum. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;92(3):678–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim H.-R., Heo Y.-M., Jeong K.-I., et al. FGF-2 inhibits TNF-α mediated apoptosis through upregulation of Bcl2-A1 and Bcl-xL in ATDC5 cells. BMB Reports. 2012;45(5):287–292. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2012.45.5.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beierle E. A., Strande L. F., Chen M. K. VEGF upregulates BCL-2 expression and is associated with decreased apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2002;37(3):467–471. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi E. H., Lee C. S., Lee J.-K., et al. STAT3-RANTES autocrine signaling is essential for tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer cells. Molecular Cancer Research. 2013;11(1):31–42. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boehme S. A., Lio F. M., Maciejewski-Lenoir D., Bacon K. B., Conlon P. J. The chemokine fractalkine inhibits Fas-mediated cell death of brain microglia. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(1):397–403. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S., Wang R., Chen L., Bennett D. A., Dickson D. W., Wang D.-S. Expression and functional profiling of neprilysin, insulin-degrading enzyme, and endothelin-converting enzyme in prospectively studied elderly and Alzheimer's brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(1):47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabo P., Relkin N., Weksler M. E. Natural human antibodies to amyloid beta peptide. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2008;7(6):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Donor information for used dental pulp derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Table 2: Donor information for used bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Table 3: Donor information for used Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Supplementary Figure 1: DPSC secretome treatment preserves morphology and improves viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to Aβ1–42.

Supplementary Figure 2: DPSC secretome stimulates the endogenous survival factor Bcl-2 and decreases the apoptotic regulator Bax.

Supplementary Figure 3: DPSC secretome contains higher concentration of Neprilysin/CD10.

Supplementary Figure 4: DPSC secretome degrade Aβ1–42 protein in vitro.

Supplementary Figure 5: DPSC secretome has neuroprotective ability against Aβ1–42 induced neurotoxicity.