Abstract

Modified-atmosphere packaging (MAP) of foods in combination with low-temperature storage extends product shelf life by limiting microbial growth. We investigated the microbial biodiversity of MAP salmon and coalfish by using an explorative approach and analyzing both the total amounts of bacteria and the microbial group composition (both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria). Real-time PCR analyses revealed a surprisingly large difference in the microbial loads for the different fish samples. The microbial composition was determined by examining partial 16S rRNA gene sequences from 180 bacterial isolates, as well as by performing terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and cloning 92 sequences from PCR products of DNA directly retrieved from the fish matrix. Twenty different bacterial groups were identified. Partial least-squares (PLS) regression was used to relate the major groups of bacteria identified to the fish matrix and storage time. A strong association of coalfish with Photobacterium phosphoreum was observed. Brochothrix spp. and Carnobacterium spp., on the other hand, were associated with salmon. These bacteria dominated the fish matrixes after a storage period. Twelve Carnobacterium isolates were identified as either Carnobacterium piscicola (five isolates) or Carnobacterium divergens (seven isolates), while the eight Brochothrix isolates were identified as Brochothrix thermosphacta by full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Principal-component analyses and PLS analysis of the growth characteristics (with 49 different substrates) showed that C. piscicola had distinct substrate requirements, while the requirements of B. thermosphacta and C. piscicola were quite divergent. In conclusion, our explorative multivariate approach gave a picture of the total microbial biodiversity in MAP fish that was more comprehensive than the picture that could be obtained previously. Such information is crucial in controlled food production when, for example, the hazard analysis of critical control points principle is used.

Extending the shelf life of fresh foods by modified-atmosphere packaging (MAP) and low-temperature storage is becoming more common (7, 11). Identification and characterization of the bacteria able to grow under these limiting conditions are important. Determination of the potential health hazards of MAP fish requires a better description of the bacteria that are able to grow on these products. The quality and safety of MAP products are largely determined by bacterial growth (12, 26). Until now, the main focus has been on specific bacteria, particularly spoilage bacteria (13). The most common spoilage bacteria reported in fish and fish products are Shewanella putrefaciens, Photobacterium phosphoreum, Brochothrix thermosphacta, and lactic acid bacteria (4). Very little is known about the total microbial flora (2, 27).

Knowledge about the total microbial biodiversity and the conditions under which the different bacteria are encountered is crucial for identification of hazards in risk evaluations of MAP fish products. The lack of selective media for, e.g., S. putrefaciens and P. phosphoreum illustrates the challenges encountered with traditional methods for examining biodiversity. In the case of P. phosphoreum, the number of bacteria has to be estimated from the appearance of the colonies on general media and by microscopic analysis. Visual classification, however, can be very subjective and may not be correct. Furthermore, culture-based methods can be biased by the inability of certain bacteria to grow on the media used. A combination of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods is thus necessary.

The benefits of using 16S rRNA gene analyses are that an unbiased classification of bacteria can be achieved (31) and that the bacteria can be analyzed directly from the food matrix (23). Culture-independent 16S rRNA gene analyses for describing microbial diversity have already been performed for bacteria in several food environments, such as MAP salad (24) and MAP smoked salmon (2, 27). No such studies, however, have yet harnessed the full potential of 16S rRNA gene analyses in combination with multivariate statistics to determine the distribution patterns of different bacteria in food matrixes. Such information is needed, e.g., when 16S rRNA gene data are used for risk assessment in hazard analysis of critical control points (HACCP) analyses (17).

The aim of the present study was to demonstrate the use of an explorative approach to characterize microbial communities. MAP salmon and coalfish stored at low temperatures were used as examples. We used a combination of conventional plating and culture-independent methods. Multivariate analyses were used to investigate patterns in the data obtained. The results of multivariate correlations of fish matrixes and storage conditions with the bacteria identified are presented below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Storage experiment with salmon and coalfish.

Filets of salmon and coalfish packed in an atmosphere consisting of 60% CO2 and 40% N2 (produced at Sekkingstad AS and Sunnmørsfisk AS) were received at Matforsk 2 days after packaging. The fish were stored at 1 and 5°C, and the packages were analyzed at the beginning of the experiment and after 3, 8, 12, and 18 days.

Bacteriological and phenotypic analyses.

For the microbial analysis a 2- to 3-mm-thick layer of 25 cm2 of a fish surface was removed, placed in 100 ml of peptone water (8.5 g of NaCl and 1.0 g of peptone in 1,000 ml), and treated for 1 min in a stomacher.

Appropriate 10-fold dilutions of the fish suspensions were spread in duplicate on agar plates containing the following media: Long-Hammer medium, which is a common medium for isolating bacteria from fish samples; Lyngby iron agar (CM 964; Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) for H2S-producing bacteria; MRS agar (CM 361; Oxoid) for lactic acid bacteria with added Delvocid (DSM; Food Specialties, Zwolle, The Netherlands) to inhibit growth of yeast; STAA agar (streptomycin thallous acetate actidione agar base type; CM 881; Oxoid) with selective supplement SR 151 for B. thermosphacta; Pseudomonads agar base (CM 559; Oxoid) with selective supplement SR 103 for pseudomonads; and Petrifilm for Enterobacteriaceae (3M Microbiology Products, St. Paul, Minn.). The Petrifilm plates were incubated at 30°C for 1 day. All other plates were incubated at 15°C for 1 week either aerobically or anaerobically. For each sampling time, colonies were isolated from plates with different media. Approximately 200 colonies were streaked for purification and frozen with glycerol at −80°C.

Phenotypic identification of Photobacterium was done both by microscopic examination and by evaluating colony appearance. The fermentation patterns were also evaluated for the Brochothrix and Carnobacterium isolates. Forty-nine substrates were tested with API 50CH test strips (bioMérieux Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.). The test was conducted as recommended by the manufacturer (bioMérieux).

16S rRNA gene sequencing of pure cultures.

The isolated bacterial cultures were plated on the same kinds of plates from which they had been isolated. To isolate DNA, single colonies were added to wells in microtiter plates containing 200 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (1:10) and five sterile glass beads (diameter, 2 mm). The microtiter plates were shaken at the maximum speed for 45 min at 5°C, and this was followed by two PCRs for each colony. The 25-μl reaction mixtures contained 0.5 μl of cell extract, 1× Dynazyme DNA polymerase II reaction buffer, 5 pmol of primer KR1F, 5 pmol of primer KR2R, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, and 2 U of Dynazyme DNA polymerase II. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 4 min, followed by five cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The final step was extension for 7 min at 72°C. The PCR products were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis before sequencing. The presequencing reaction included treating 8 μl of the PCR product with 10 U of exonuclease I (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) and 2 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Amersham) at 37°C for 15 min. The enzymes were inactivated by heating at 80°C for 15 min. Sequencing was done with a Big Dye Terminator v 2.0 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and a 377 DNA sequencer. The sequencing mixture was prepared as recommended by the manufacturer. The sequencing primers described by Turner et al. (30) were used. All 10 internal primers were used for the full-length sequences, while primer 515F was used for the partial sequences.

Direct extraction of DNA from the fish matrix.

There are special requirements for DNA extraction protocols for bacterial communities in complex samples (1, 2, 18, 25). Extraction methods that fail to remove bacteria from the food matrix or fail to lyse certain bacteria introduce bias in the subsequent analyses (1). The extraction protocol used in this work was evaluated with both naturally colonized and spiked samples. An extensive method optimization procedure was performed in order to determine the final protocol. The criteria used in the optimization process were level of PCR inhibitors, DNA recovery, and potential bias due to differential lysis of the bacteria in the sample.

A combination of different centrifugation steps (first centrifugation twice at low speed to get rid of the solid matter of the fish and then centrifugation at high speed to sediment the bacteria) seemed to work best. It was difficult to obtain a clear supernatant with the salmon samples due to the high fat content. Extraction of DNA from the salmon samples was improved after purification with a Percoll gradient. A mechanical approach was used to ensure complete lysis of the bacteria present (see below).

The following optimized DNA extraction protocol was used. During the storage experiment tubes containing 50 ml of a fish suspension from the stomacher solution were frozen. For DNA isolation the tubes were thawed overnight in a refrigerator. The fish suspension was diluted with peptone water to obtain a volume of 100 ml and centrifuged at 700 rpm for 1 min (Biofuge Fresco; Kendro Laboratory Products). The supernatant was removed until 10 ml was left, 90 ml of peptone water was added, and centrifugation was performed again. The supernatant was added to the first tube and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. The pellet was diluted in 10 ml of TE buffer (pH 8) and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g and diluted in 5 ml of TE buffer. To estimate the number of bacteria recovered with this assay, 0.5 ml was diluted, plated on Long-Hammer medium, and incubated at 15°C for 1 week.

The salmon samples were treated in a Percoll gradient (NMKL method) before lysis and extraction of DNA. Four 0.9-ml samples of the final fish suspension were layered on top of 0.6 ml of Percoll (Amersham) in Eppendorf tubes. The tubes were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm (Biofuge Fresco) for 1 min. The supernatant was removed until 0.1 ml was left. What remained was transferred to another tube, mixed with 1.2 ml of H2O, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (Biofuge Fresco) for 5 min. The supernatant was removed until only 0.1 ml was left. Then 1.0 ml of TE buffer was added, mixed with the pellet, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm (Biofuge Fresco) for 5 min. This time the supernatant was removed until 0.3 ml was left. The contents of the four tubes prepared from the same sample were pooled.

Glass beads (0.25 g; diameter, 106 μm; Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) were added to 0.5-ml portions of suspensions of coalfish and to 0.5-ml suspensions of the Percoll-treated salmon. The bacterial cells were lysed with a Fast-Prep bead beater (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.). The treatment was performed at the maximum speed for 40 s. The DNA in the supernatant was purified with a DNeasy tissue kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

The total amounts of bacteria in the samples were determined by 5′ nuclease PCR by using universally conserved regions in the 16S rRNA gene as the target with the primers and probes described by Nadkarni et al. (20). The following amplification profile was used: 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 60°C for 1 min. The reactions were performed with the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). We used carboxyfluorescein as a reporter dye and 6-carboxy-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylrhodamine as a quencher. A threshold signal was chosen when the signal could be detected. This gave the threshold cycle (Ct), which defined the first cycle for which a signal could be detected.

Standard curves for quantification were prepared from DNA dilution series. Reliable standard curves for bacteria added to the fish matrixes were not possible due to the high intrinsic microbial loads in the samples. Polynomial regressions were used to construct the standard curves (Microsoft Excel 2000; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Wash.). The reason for using polynomial regression is the influence of bacterial DNA contamination in the DNA polymerase for packages containing small amounts of bacteria.

T-RFLP analysis.

A terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis was performed by using the protocol described above for real-time PCR, but without a probe. The T-RFLP analysis was replicated twice for each DNA purification. The forward primer was 5′ labeled with carboxyfluorescein, while the reverse primer was labeled with 6-carboxy-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylrhodamine. Five microliters of the amplification product was cut with a mixture of AluI, RsaI, MspI, and MseI (10 U each) in 20 μl (total volume) of 1× NEB buffer 2 (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) for 8 h. The products were subsequently separated on a 3% agarose gel, and the fragments were detected by using a Typhoon scanner (Amersham). Quantification was performed by using the ImageMaster Total Lab software (Amersham).

16 rRNA gene sequence analyses of DNA directly retrieved from the fish matrix.

The amplification conditions described above for the T-RFLP analysis were used. The products were then cloned with a TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). TOP 10 One Shot chemically competent cells were used. Transformation of the cells was performed as described in the TOPO TA cloning kit manual. The Rapid One Shot chemical transformation protocol was used (Invitrogen). Plasmids from the positive colonies were isolated by resuspending a colony in 30 μl of water, heating it to 99°C for 5 min, removing the cell debris by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm (Biofuge Fresco) for 1 min, and transferring 25 μl to a new tube. The insert was amplified with primers HU (5′-CGC CAG GGT TTT CCC AGT CAC GAC G-3′) and HR (5′-GCT TCC GGC TCG TAT GTT GTG TGG-3′), which are specific for the Bluescript vector. The following amplification conditions were used: 95°C for 4 min and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The reaction was ended with an extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Finally, the cloned fragments were sequenced by using the protocol described above for DNA sequencing of pure cultures.

Phylogenetic reconstruction.

Sequences of representative strains were selected from the GenBank nucleotide sequence database (June 2003) based on searches with the BLAST program. The sequences determined in this work were aligned with this selection of representative sequences by using the alignment software Clustal W (29). The alignments were then manually edited by using the program BioEdit (15).

A tree was constructed by using Tamura-Nei distances (28) and the Minimum Evolution algorithm provided in the MEGA 2 software package (16). The statistical support for the branches in the trees was tested by bootstrap analysis.

Multivariate statistical analyses.

The patterns within sets of data were evaluated by principal-component analysis (PCA), while the correlations between different sets of data were determined by using partial least-squares (PLS) regression (The Unscrambler; Camo Inc., Corvallis, Oreg.). The data were analyzed by using full cross-validation with centered data. The variables were weighted according to their standard deviations.

PCA is a bilinear modeling method which gives an interpretable overview of the main information in a multidimensional data table. The information carried by the original variables is projected onto a smaller number of underlying (latent) variables called principal components. The first principal component covers as much of the variation in the data as possible. The second principal component is orthogonal to the first and covers as much of the remaining variation as possible, and so on. By plotting the principal components, one can view relationships between different variables and detect and interpret sample patterns, groupings, similarities, or differences.

PLS regression is a method for identifying the variations in a data table (X variables) that are relevant for another data table (Y variables), with explanatory or predictive purposes. PLS regression is a bilinear modeling method in which information in the original X data is projected onto a small number of underlying (latent) variables called PLS components. The Y data are actively used in estimating the latent variables to ensure that the first components are the components that are most relevant for predicting the Y variables. Interpretation of the relationship between X data and Y data is then simplified, as this relationship is concentrated on the smallest possible number of components. By plotting the first PLS components one can view main associations between X variables and Y variables and also relationships within X data and within Y data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

DNA extraction from the total microbial community.

There was a relatively low content of PCR inhibitors in the purified DNA. Up to 10% of the DNA could be used without detectable inhibition of the PCR (data not shown). The reproducibility of DNA purification was evaluated by using three independent extracts from 18 (9 salmon and 9 coalfish) fish suspensions (after stomacher treatment). We determined that the average standard deviation was approximately 0.7 log10 CFU/cm2. DNA was also purified in triplicate from gram-negative (Shewanella) and gram-positive (Brochothrix and Carnobacterium) bacteria commonly encountered in MAP fish products. The overall standard deviation for all these purifications was 0.2 log10 CFU/cm2. This indicates that there were low levels of differential lysis for the bacteria tested. Lysis was also evaluated empirically by microscopy. We concluded that our protocol is robust with respect to removal of PCR inhibitors, lysis, and reproducibility.

Quantification and characterization of the total bacterial flora.

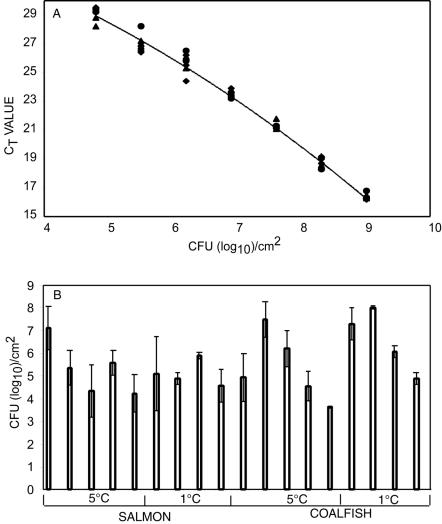

The 5′ nuclease PCR quantification analysis (Fig. 1A) showed that there was great divergence in the total amounts of bacteria in the different fish packages after storage (Fig. 1B). The 5′ nuclease PCR signal range for the salmon packages was 4 to 7 log10 CFU/cm2, while the range for the coalfish packages was 4 to 8 log10 CFU/cm2 (Fig. 1B). The variation was even larger early in the storage period. There were no significant differences between the conditions tested (data not shown). The divergence may have been due to the presence of high levels of fecal contamination of the fish samples. The total number of bacteria per square centimeter was also analyzed by plate counting by using Long-Hammer medium and incubation at 15°C, as recommended by Emborg et al. (10). The total numbers of bacteria were in the same range as the numbers determined by the 5′ nuclease PCR.

FIG. 1.

Real-time PCR quantification of the total amount of bacteria. (A) Standard curves for quantification of B. thermosphacta MF154 (•), Shewanella sp. strain MF186 (⧫), and C. divergens MF151 (▴). The polynomial regression curve is described by the following formula: y = −0.0047x2 − 0.1146x + 12,091 (R2 = 0.99), where y is log10 CFU per square centimeter and x is the Ct value. (B) Individually packed MAP samples were analyzed at the end of the storage period for salmon and coalfish packages stored for 12 and 18 days at 1 and 5°C, respectively. The bacteria were quantified by using the transformation formula described above and transforming the Ct data to the corresponding number of CFU per gram. The error bars indicate standard deviations for three individual analyses of each package.

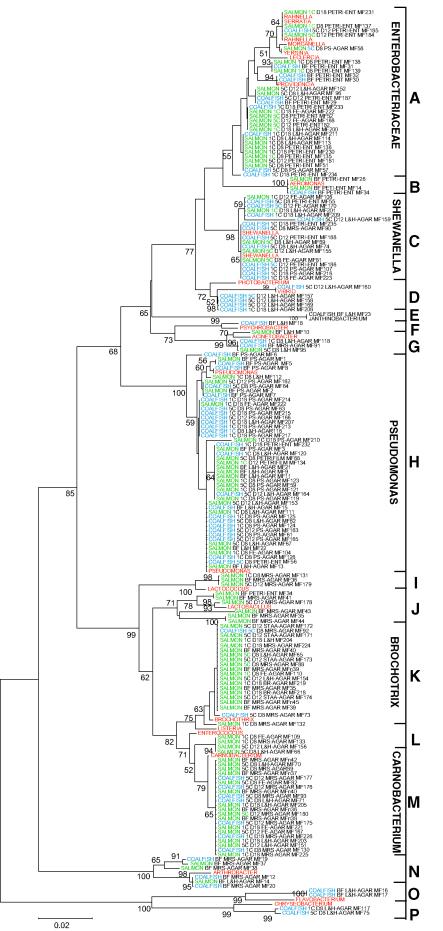

Sixteen different groups (groups A to P) were identified for the bacteria retrieved by plating on the media described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 2). In addition, Streptococcus (group Q), propionibacteria (group R), and clostridia (group S) were detected by direct cloning and sequencing. Interestingly, a clone with 100% 16S rRNA gene identity to Clostridium botulinum was identified (in group S). The microbial biodiversity was surprisingly high considering the relatively defined matrixes analyzed.

FIG.2.

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on 16S rRNA genes from bacterial isolates. The tree was constructed by using Tamura-Nei distances (28) and the Minimum Evolution algorithm provided in the MEGA 2 software package. The numbers at the nodes indicate the percentages of 1,000 bootstrap trees in which the clusters descending from the nodes were found. Only values greater than 50% are shown. The origins of the strains are indicated by colors, as follows: blue, coalfish; green, salmon; and red, sequences from GenBank. Abbreviations: BF, before storage; 1C and 5C, storage at 1 and 5°C, respectively; D8, D12, and D18, storage for 8, 12, and 18 days, respectively; PETRI-ENT, Petrifilm for Enterobacteriaceae; PS-AGAR, Pseudomonads agar base; L&H-AGAR and L&H, Long-Hammer agar; FE-AGAR, Lyngby iron agar; MRS-AGAR, MRS agar; STAA-AGAR, STAA agar; BR-AGAR, STAA agar with supplement for Brochotrix. The strain designations are indicated, as are the different groups of bacteria identified (groups A to P). Sequences having the following GenBank accession numbers were used: AF430124, AF336350, AF200329, AF134183, M58798, AF184247, AJ271009, AF061001, AF493646, Y08846, AB063479, X54259, AF461011, Z19107, AJ301684, AF094745, AJ297354, AJ312213, U88439, AJ233434, U90758, AB038029, and AF366380. A high-resolution version of the tree is available upon request.

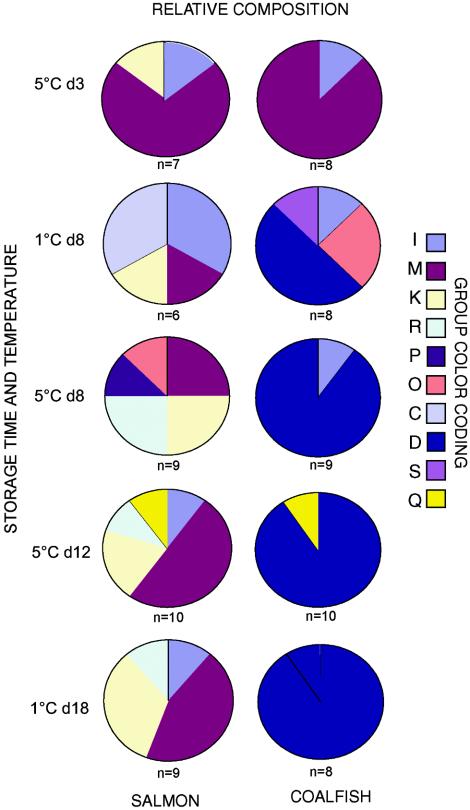

Clear patterns were observed when we analyzed sequences retrieved directly from the fish matrixes (Fig. 3). Bacteria belonging to the Carnobacterium group (group M) dominated early in the storage period in both salmon and coalfish. The dominant flora changed during storage to the Photobacterium group (group D) for the coalfish packages. There was an approximately 1:1 mixture of Carnobacterium (group M) and Brochothrix (group K) in the salmon packages after storage. There were no clear trends related to the storage temperature, but the presence of Streptococcus (group Q) in both salmon and coalfish packages only when they were stored at 5°C for 12 days may indicate that this bacterium does not grow at 1°C.

FIG. 3.

Relative distributions of bacteria based on the directly retrieved sequences. The relative compositions of the bacterial floras in the different samples are indicated. The colors indicate the groups that were present in the samples; these groups included the groups shown in Fig. 2 and also Streptococcus (group Q), propionibacteria (group R), and clostridia (group S). d3, d8, d12, and d18, storage for 3, 8, 12, and 18 days, respectively.

The microbial compositions of the samples directly retrieved from the fish matrixes were also analyzed by the T-RFLP procedure. The same trends were observed with the T-RFLP data as with the cloned sequences. The T-RFLP results supported the conclusions drawn from the cloned sequence data, but they did not provide additional information (data not shown).

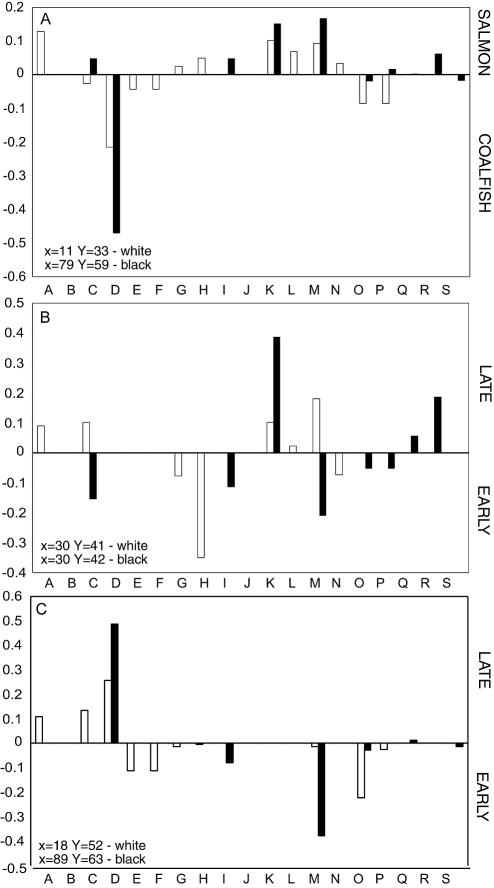

PLS regression was used to investigate the correlation between the bacterial group frequency data obtained by direct cloning and the results for the colonies isolated from Long-Hammer medium (Fig. 4). Regressions were constructed for the fish matrixes (Fig. 4A) and storage time (Fig. 4B and C). The most notable difference when the direct cloning and colony data were compared was the apparent underrepresentation of Photobacterium (group D) in the coalfish packages with the colony data (Fig. 4A). This underrepresentation was indicated by a score closer to zero. The same underrepresentation was also observed late in the storage period for the coalfish packages (Fig. 4C). Part of this underrepresentation may have been due to technical difficulties in growing Photobacterium. Enterobacteriaceae were associated with the salmon samples as determined with the colony data, while these bacteria were not detected by direct cloning (Fig. 4A). There was clear dominance of Carnobacterium early in storage for the directly retrieved sequences, while this was not the case for sequences retrieved from the colonies (Fig. 4B and C). Pseudomonas and Flavobacterium dominated early in the salmon and coalfish packages, respectively, as determined by the colony-based approach, while these bacteria were not detected by direct cloning (Fig. 4B and C).

FIG. 4.

PLS regression for 16S rRNA gene data with respect to the fish matrix (A), the storage time for salmon (B), and the storage time for coalfish (C). The PLS regression analysis was done by using bacterial group frequency data that were centered and normalized by dividing on the standard deviation for each factor as X, while the fish matrix (A) and storage time (B) were Y in the PLS regression. The open bars show data for strains isolated from Long-Hammer medium, while the solid bars show data for the directly retrieved sequences. The first principal component is shown. The explained variance for X (bacterial group frequency data) and the explained variance for Y (fish matrix and time) are shown in each panel for the open bars (colony) and solid bars (direct).

There were better correlations between the parameters analyzed (matrix and storage time) and the bacteria identified for the direct cloning approach than for the growth-based approach. This was shown by the higher explained variance for the directly retrieved data than for the colony data (Fig. 4). One explanation for this could be that there was more noise in the colony data than in the data obtained from the directly retrieved sequences.

Characterization of the dominant microbial flora.

It is well established that P. phosphoreum is associated with colonization of MAP fish (5-10, 13, 14, 19). Our partial Photobacterium 16S rRNA gene sequences showed 100% identity to this species. The presence of Carnobacterium and Brochothrix in MAP fish products, however, is not well documented (3, 10, 21). This prompted further characterization of these bacteria by full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and by determining the fermentation patterns.

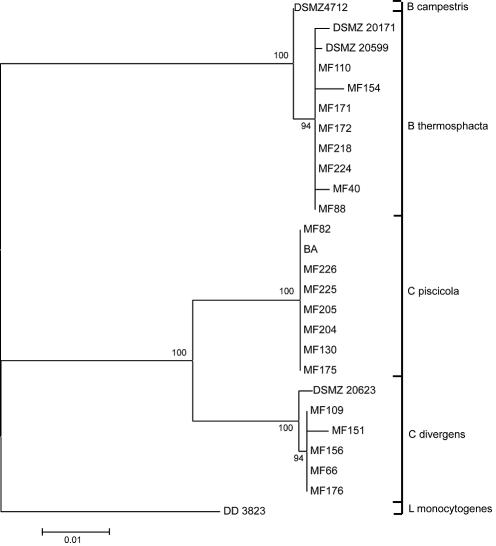

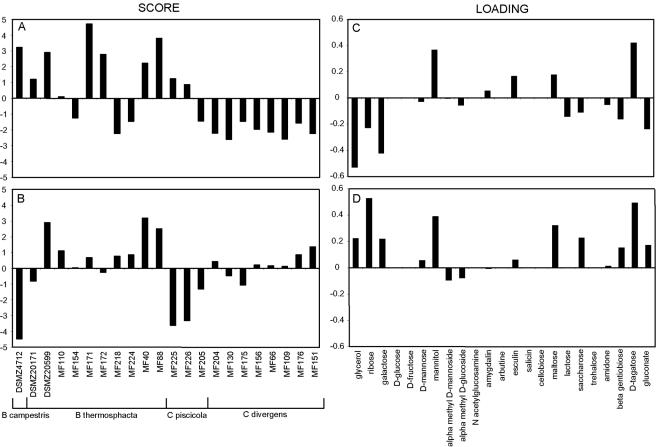

The full-length 16S rRNA gene analyses showed that Carnobacterium piscicola and Carnobacterium divergens were the dominant Carnobacterium species, while B. thermosphacta was the dominant Brochothrix species (Fig. 5). The fermentation patterns of these genera were also evaluated (Table 1). PCA of the growth patterns (Fig. 6) showed that the substrate requirements for Carnobacterium were relatively consistent for the two species identified. The requirements, however, were very divergent among the different Brochothrix isolates. The most important substrates, which separated the strains, are glycerol, ribose, galactose, mannitol, and d-tagatose. Multivariate regression analyses were used to relate the microbial species and fish matrix to substrate requirements. However, only low or no correlations were determined (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic reconstruction based on full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences for species determination for the Brochothrix and Carnobacterium isolates. The tree was constructed by using Tamura-Nei distances (28) and the Minimum Evolution algorithm provided in the MEGA 2 software package. The numbers at the nodes indicate the percentages of 1,000 bootstrap trees in which the clusters descending from the nodes were found. Only values greater than 50% are shown. Most of the sequence accession numbers are shown in Table 1. Additional accession numbers are as follows: U84150 (L. monocytogenes strain DD 3823), AF184247 (C. piscicola strain BA), M58816.1 (C. divergens strain DSMZ 20623), and AY543035 (C. piscicola strain MF82).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Brochothrix and Carnobacterium isolates

| Strain | Accession no. | Origin | Growth with the following substratesa:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyce- rol | Ri- bose | Galac- tose | d- Glu- cose | d- Fruc- tose | d- Man- nose | Man- nitol | α-Methyl- d-manno- side | α-Methyl- d-gluco- side | N-Acetyl- glucos- amine | Amyg- dalin | Arbu- tin | Escu- lin | Sali- cin | Cello- biose | Malt- ose | Lac- tose | Saccha- rose | Treha- lose | Ami- don | β-Gentio- biose | d-Taga- tose | Gluco- nate | |||

| B. campestris DSMZ 4712 | AY543038 | Soil | −b | −(+) | − | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | − | −(+) | − | − |

| B. thermosphacta strains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DSMZ 20171 | AY543023 | Pork | −+ | (+)+ | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | −+ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| DSMZ 20599 | AY543024 | Unknown | −+ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | −(+) |

| MF110 | AY543017 | Salmon | (+)+ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | − | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | (+)(+) | −(+) |

| MF154 | AY543020 | Salmon | (+)+ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −+ | − | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)− | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | − | −(+) |

| MF171 | AY543022 | Salmon | − | (+)+ | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | (+)(+) | (+)+ | − |

| MF172 | AY543025 | Salmon | − | (+)+ | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −+ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | −(+) |

| MF218 | AY543026 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF224 | AY543027 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | − | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF40 | AY543028 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − |

| MF88 | AY543029 | Salmon | −(+) | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − |

| C. piscicola strains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MF225 | AY543033 | Salmon | −+ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | −(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| MF226 | AY543034 | Coalfish | −+ | − | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −+ | −(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| MF205 | AY543032 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| MF204 | AY543031 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | − | (+)− | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF130 | AY543018 | Coalfish | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | −(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| MF175 | AY543030 | Coalfish | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | − | −(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| C. divergens strains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MF156 | AY543021 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF66 | AY543036 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | − | − | ++ | −(+) | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF109 | AY543016 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | −(+) | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF176 | AY543037 | Coalfish | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)(+) | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

| MF151 | AY54019 | Salmon | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −+ | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+)+ | ++ | ++ | ++ | −(+) | ++ | ++ | − | ++ | − | (+)(+) |

The following substrates did not support growth of the strains tested: erythrol, d-arabinose, l-arabinose, d-xylose, l-xylose, adonitol, beta-methyl-xyloside, l-sorbose, rhamnose, dulcitol, inositol, sorbitol, inulin, melezitose, d-raffinose, glycogen, xylitol, d-turanose, d-lyxose, d-fucose, l-fucose, d-arabitol, l-arabitol, 2-eto-gluconate, 5-eto-gluconate, and melibiose.

−, no signal; −(+), weak signal after 48 h; −+, strong signal after 48 h; (+)(+), weak signal after both 24 and 48 h; (+)+, weak signal after 24 h and strong signal after 48 h; ++, strong signal after both 24 and 48 h.

FIG. 6.

PCA of the substrate requirements for the Brochothrix and Carnobacterium isolates. The data in Table 1 were subjected to PCA (see Materials and Methods for details). Principal component 1 (A and C) explains 36% of the variance, while principal component 2 (B and D) explains 24% of the variance in the data. (A and B) Score matrix for principal components 1 and 2. (C and D) Loading matrix for principal components 1 and 2.

Carnobacterium is common in fish gastrointestinal tracts (22). The dominance of this bacterium early in storage supports the hypothesis that there was fecal contamination in the MAP products. Brochothrix, on the other hand, has not been associated yet with fish gastrointestinal tracts. The relatively large amounts of Brochothrix in the salmon samples early during storage (similar to the amounts of Carnobacterium), however, may also indicate that there is fecal contamination by this bacterium.

Implications for future production of safe MAP fish products.

The increasing incidence of food-borne diseases in the industrialized world may be due in part to changes in food-processing strategies. We are not able to control pathogens despite the introduction of the HACCP concept (17). The limiting factor is probably the analytical tools for hazard identification. For instance, we did not detect clostridia by plating techniques, although a wide range of conditions, including anaerobic conditions, were tested. By using direct analyses, on the other hand, a clone with 100% 16S rRNA gene identity to C. botulinum was identified. This bacterium is a potential threat in MAP products, although it is not possible to determine if the bacterium is viable by 16S rRNA gene analyses (26). The multivariate explorative approach presented in this paper may be used to increase our knowledge about potential hazards in MAP fish in order to use the HACCP concept properly and also in other fields of food safety analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agricultural Food Research Foundation and by TINE BA, Norway.

We thank Thomas Eie for providing the MAP fish material and Ragnhild Norang for carefully reading and commenting on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burgmann, H., M. Pesaro, F. Widmer, and J. Zeyer. 2001. A strategy for optimizing quality and quantity of DNA extracted from soil. J. Microbiol. Methods 45:7-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cambon-Bonavita, M. A., F. Lesongeur, S. Menoux, A. Lebourg, and G. Barbier. 2001. Microbial diversity in smoked salmon examined by a culture-independent molecular approach—a preliminary study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connil, N., H. Prevost, and X. Dousset. 2002. Production of biogenic amines and divercin V41 in cold smoked salmon inoculated with Carnobacterium divergens V41, and specific detection of this strain by multiplex-PCR. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:611-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalgaard, P. 2000. Fresh and lightly preserved seafood, p. 110-139. In A. A. Jones (ed.), Shelf life evaluation of foods, 2nd ed. Aspen Publishing Inc., Frederick, Md.

- 5.Dalgaard, P. 1995. Modelling of microbial activity and prediction of shelf life for packed fresh fish. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 26:305-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalgaard, P., L. Garcia Munoz, and O. Mejlholm. 1998. Specific inhibition of Photobacterium phosphoreum extends the shelf life of modified-atmosphere-packed cod fillets. J. Food Prot. 61:1191-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgaard, P., L. Gram, and H. H. Huss. 1993. Spoilage and shelf-life of cod fillets packed in vacuum or modified atmospheres. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 19:283-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalgaard, P., G. P. Manfio, and M. Goodfellow. 1997. Classification of photobacteria associated with spoilage of fish products by numerical taxonomy and pyrolysis mass spectrometry. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 285:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debevere, J., and G. Boskou. 1996. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging on the TVB/TMA-producing microflora of cod fillets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 31:221-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emborg, J., B. G. Laursen, T. Rathjen, and P. Dalgaard. 2002. Microbial spoilage and formation of biogenic amines in fresh and thawed modified atmosphere-packed salmon (Salmo salar) at 2 degrees C. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:790-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faber, J. 1991. Microbiological aspects of modified-atmosphere technology—a review. J. Food Prot. 54:58-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gram, L. 1992. Evaluation of bacteriological quality of seafood, p. 269-282. In J. Lista (ed.), Quality assurance in the fish industry. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 13.Gram, L., and H. H. Huss. 1996. Microbiological spoilage of fish and fish products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 33:121-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guldager, H. S., N. Boknaes, C. Osterberg, J. Nielsen, and P. Dalgaard. 1998. Thawed cod fillets spoil less rapidly than unfrozen fillets when stored under modified atmosphere at 2 degrees C. J. Food Prot. 61:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall, T. A. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMeekin, T. A., J. Brown, K. Krist, D. Miles, K. Neumeyer, D. S. Nichols, J. Olley, K. Presser, D. A. Ratkowsky, T. Ross, M. Salter, and S. Soontranon. 1997. Quantitative microbiology: a basis for food safety. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:541-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McOrist, A. L., M. Jackson, and A. R. Bird. 2002. A comparison of five methods for extraction of bacterial DNA from human faecal samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mejlholm, O., and P. Dalgaard. 2002. Antimicrobial effect of essential oils on the seafood spoilage micro-organism Photobacterium phosphoreum in liquid media and fish products. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 34:27-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadkarni, M. A., F. E. Martin, N. A. Jacques, and N. Hunter. 2002. Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad-range (universal) probe and primers set. Microbiology 148:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paludan-Muller, C., P. Dalgaard, H. H. Huss, and L. Gram. 1998. Evaluation of the role of Carnobacterium piscicola in spoilage of vacuum- and modified-atmosphere-packed cold-smoked salmon stored at 5 degrees C. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 39:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ringo, E., M. S. Wesmajervi, H. R. Bendiksen, A. Berg, R. E. Olsen, T. Johnsen, H. Mikkelsen, M. Seppola, E. Strom, and W. Holzapfel. 2001. Identification and characterization of carnobacteria isolated from fish intestine. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudi, K. 2003. Application of 16S rDNA arrays for analyses of microbial communities. Recent Res. Dev. Bacteriol. 1:35-44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudi, K., S. L. Flateland, J. F. Hanssen, G. Bengtsson, and H. Nissen. 2002. Development and evaluation of a 16S ribosomal DNA array-based approach for describing complex microbial communities in ready-to-eat vegetable salads packed in a modified atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1146-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudi, K., and K. Jakobsen. 2001. Protocols for nucleic acid-based detection and quantification of microorganisms in water, p. 63-74. In P. Rochelle (ed.), Environmental molecular microbiology: protocols and applications. Horizon Scientific Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom.

- 26.Stammen, K., D. Gerdes, and F. Caporaso. 1990. Modified atmosphere packaging of seafood. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 29:301-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suau, A., R. Bonnet, M. Sutren, J. J. Godon, G. R. Gibson, M. D. Collins, and J. Dore. 1999. Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4799-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura, K., and M. Nei. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10:512-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner, S., K. M. Pryer, V. P. Miao, and J. D. Palmer. 1999. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 46:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woese, C. R. 1987. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 51:221-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]