Abstract

Background: Macular pigment (MP) levels correlate with brain concentrations of lutein (L) and zeaxanthin (Z), and have also been shown to correlate with cognitive performance in the young and elderly.

Objective: To investigate the relationship between MP, serum concentrations of L and Z, and cognitive function in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1, n = 105) and in subjects with AMD (Group 2, n = 121).

Methods: MP was measured using customized heterochromatic flicker photometry and dual-wavelength autofluorescence; cognitive function was assessed using a battery of validated cognition tests; serum L and Z concentrations were determined by HPLC.

Results: Significant correlations were evident between MP and various measures of cognitive function in both groups (r = –0.273 to 0.261, p≤0.05, for all). Both serum L and Z concentrations correlated significantly (r = 0.187, p≤0.05 and r = 0.197, p≤0.05, respectively) with semantic (animal) fluency cognitive scores in Group 2 (the AMD study group), while serum L concentrations also correlated significantly with Verbal Recognition Memory learning slope scores in the AMD study group (r = 0.200, p = 0.031). Most of the correlations with MP, but not serum L or Z, remained significant after controlling for age, gender, diet, and education level.

Conclusion: MP offers potential as a non-invasive clinical biomarker of cognitive health, and appears more successful in this role than serum concentrations of L or Z.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, biomarker, cognitive function, lutein, macular pigment, zeaxanthin

INTRODUCTION

Carotenoids are a group of plant pigments which are responsible for the bright color of a variety of foods in nature. They are lipid soluble and divided into oxygenated xanthophylls, and non-oxygenated (hydrocarbon) carotenes [1]. The macula, which is the central part of the retina, is responsible for fine detailed vision. Of interest, this specialized part of the retina specifically accumulates the xanthophyll carotenoids lutein (L), zeaxanthin (Z), and meso-zeaxanthin (MZ) (in a ratio of 1:1:1), where they are collectively referred to as macular pigment (MP) [2]. The fact that the macula selects these three carotenoids from the more than 30 carotenoids available in human blood [3] suggests that L, Z, and MZ have a specific role to play at this tissue [4].

Indeed, it has been shown that MP’s constituent carotenoids can prevent against oxidative damage to the macula caused by reactive oxygen species, due to the antioxidant nature of their polyene chains, which actively quench these unstable molecules [5–7]. Also, the optical properties of MP reduce the production of reactive oxygen species at the macula, by absorbing short wavelength (blue) light before it is incident on the macula [8]. Importantly, the antioxidant and light filtering properties of MP confer protection against age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which is a disease of the macula caused (at least in part) by cumulative photo-oxidative injury, and is the most common cause of blindness in the Western world [9, 10].

Research to date has demonstrated the importance of MP for protecting against AMD progression [11–14], and has also established that MP plays an important role in enhancing visual function in both diseased [15–19] and non-diseased [20] eyes, via the optical (light-filtering) properties of this pigment [21, 22]. Of note, it has been shown that supplementation [23–26], and in particular supplementation with all three carotenoids (MZ, L, and Z) in a mg ratio of 10:10:2 may offer the best means of enriching MP across its spatial profile [27–29], and impacts positively on visual function (e.g., contrast sensitivity and glare disability) in human subjects [20].

Recent research has identified that L and Z are also present in brain tissue, specifically the cerebellum, pons, and the frontal/occipital cortices [30, 31]. L and Z were also detected in the hippocampus and prefrontal and auditory cortices of human brain tissue [32]. Interestingly, it has been found that MP levels correlate with concentrations of L and Z (particularly L) in the primate brain [31]. This had led researchers to speculate that the macular carotenoids may also have an antioxidant role in the brain, similar to that in the human retina (the retina is part of the central nervous system). Possible functions of carotenoids in the brain include: antioxidant; anti-inflammatory; structural and functional enhancement of synaptic membranes and gap junction communication, and thereby may ultimately protect against insult to cognition [33, 34]. Recent work by our group has shown that patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) exhibit significantly less MP, poorer vision, and a higher occurrence of AMD when compared to control subjects [19]. Moreover, in a subsequent clinical trial, we found that supplementation with the macular carotenoids (MZ, Z, and L) benefited patients with AD, in terms of increases in MP and in terms of clinically meaningful improvements in visual function [35]. In another example, Rinaldi et al. have shown that in patients with AD, plasma concentrations of L and Z were lower in comparison to control subjects, with a significant and inverse relationship observed between L concentrations and dementia severity [36, 37]. In another study, supplemental L resulted in improved performance in a range of cognitive tests in unimpaired older women [38]. Indeed, it has been shown that a positive relationship exists between MP levels and cognitive performance in unimpaired and mildly cognitively impaired adults [39–41]. Recent work has also shown that MP levels are significantly related to better global cognition, verbal learning and fluency, recall, and processing and perceptual speed, whereas serum L and Z levels were only significantly related to verbal fluency in older adults with normal cognitive function [42]. Taken together, these studies suggest that MP’s constituent carotenoids may play a role in cognitive function, and given the relationship between MP and brain carotenoid levels, it is reasonable to hypothesize that MP could be used as a biomarker for cognitive function and/or AD; however, additional study in this area is needed.

In this cross sectional baseline study, we report on cognition and its relationship with MP and serum concentrations of its carotenoids in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and subjects with AMD (Group 2) from the Central Retinal Enrichment Supplementation Trials (CREST) study [43].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CREST is a double blind, parallel group, and randomized controlled clinical trial, which studies the impact of macular carotenoids (L, Z, and MZ) on visual function in two subject populations; normal subjects with low MP (non-diseased) (Trial 1), and subjects with early AMD (Trial 2). Clinical assessments were conducted by the researchers J.D. (Trial 1) and K.O.A. (Trial 2), who were suitably trained on all aspects of the CREST protocol. The methods for the CREST clinical trial have been previously described in detail [43]. The primary outcome measure in both trials is Contrast Sensitivity (CS) at 6 cycles per degree, while secondary outcome measures include CS at other spatial frequencies, glare disability, visual acuity, light scatter, photo stress recovery, foveal architecture, subjective visual function, serum carotenoid concentrations, MP, and cognitive function. Reading acuity, reading speed, and AMD morphology are also assessed in Trial 2.

Subjects

Recruitment for Trial 1 involved organized national and local advertising campaigns, including in Irish newspapers, on radio stations and through online adverts. Flyers were also distributed to the general public. In addition, educational events were held for optometrists, ophthalmologists, and general practitioners, which created awareness of the trial, and aided in recruitment. Following the recruitment campaign, interested subjects attended our Vision Research Centre to undergo an initial assessment which determined if they met the eligibility criteria for inclusion.

Inclusion criteria for Trial 1 (Group 1) included: (1) ≥18 years; (2) best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/6 or better; (3) no more than five diopters spherical equivalence of refraction; (4) no previous consumption of supplements containing L, Z, and/or MZ; (5) no ocular pathology; and (6) MP at 0.25 degrees eccentricity of less than 0.5 optical density units.

Subjects recruited into Group 1 were those who exhibited no abnormalities in their vision following a range of tests including BCVA, fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and completion of a general health questionnaire, all under the supervision of a retinal specialist. Thus, this group of subjects were adjudged “normal” in every respect, except that their central MP levels were below-average. Low MP, for purposes of selecting Group 1 study subjects, was defined as 0.5 optical density units or below at 0.25 degrees eccentricity; 85% of Group 1 subjects were below this level, 95% were below 0.58, and none exceeded 0.7 units. The reasons for recruiting this Low MP group are detailed as follows: 1) Subjects with Low MP may have a higher tendency to exhibit beneficial effects following supplementation because of the higher likelihood for an increase in MP levels; 2) Subjects recruited in Group 1 had visual acuity of at least 6/6 and therefore typically exhibit ceiling effects on visual function tests. The impact of MP augmentation on visual function may be more evident in the low MP group given that these subjects have a wider range of possible/probable MP increase; 3) The Group 1 subjects may have certain genetic/lifestyle characteristics which preclude efficient absorption of the macular carotenoids at the macula; 4) One of the recommendations from the Collaborative Optical Macular Pigment Assessment Study (COMPASS) [44] was that further studies on the impact of MP augmentation on visual function should focus on individuals with low MP and therefore the current study was designed to fill this gap in the scientific literature; 5) Interestingly, in the AREDS2 study [11], beneficial effects of MP’s constituent carotenoids in terms of visual function and progression to advanced AMD were demonstrated more in subjects with low dietary intake of these carotenoids (and perhaps low MP group given that L, Z, and MZ are not synthesized de novo and can only be obtained through the diet and supplements). Of note, this is the first clinical trial to specifically recruit subjects with Low MP.

Recruitment for Trial 2 was carried out with the help of eye centers, who were used to raise awareness of the trial. As for Trial 1 above, educational events were held for optometrists, ophthalmologists, and general practitioners, which created awareness of the trial, and aided in recruitment. Interested and potentially suitable subjects attended our vision research center for a screening examination with an emphasis on the presence of early AMD. This was carried out by a consultant ophthalmologist with a special interest in AMD (SB). Subjects who were deemed suitable for the trial following this screening visit had stereo fundus photographs taken, which were then sent to the Reading Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital, London for confirmation of the presence of early AMD in subject eyes. These subjects were then invited to participate in Trial 2.

Inclusion criteria for Trial 2 (Group 2) included: 1) BCVA of 6/12 or better; 2) no more than five diopters spherical equivalence of refraction; 3) no previous consumption of supplements containing L, Z, and/or MZ; 4) no retinal pathology beyond AMD; and 5) no diabetes mellitus.

Subjects were included in the early AMD category (Group 2) if early AMD was seen in at least one eye based on the grading of a fundus photograph from one to eight [43] on the Age Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) 11-step severity scale [45].

Demographic variables

A demographic and lifestyle questionnaire was provided to all subjects, which obtained details on: address and contact number, education level, occupation, ethnicity, smoking habits (frequency and history), alcohol intake (average weekly consumption and frequency), dietary intake of L and Z using an L/Z screener [19], exercise (sessions per week and duration), light exposure (time spent outdoors, use of sunglasses, photochromic lenses), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), medical history, blood pressure, and ocular medical history. For the purposes of this publication, the following demographic and behavioral variables were included in the analysis: age, gender, smoking habits, diet score, exercise routine, education level, alcohol intake, and BMI.

Ethical approval

All subjects provided written consent of their willingness to enroll, and participate in, the CREST trials. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the European Research Council (ERC) and the Ethics Committee of the Waterford Institute of Technology (WIT), Waterford, Ireland. The trials also adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and followed the ethics code with respect to subject recruitment, testing and data protection.

Macular pigment measurement

MP levels were measured firstly by customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP) using the Macular Densitometer (Macular Metrics Corp, Providence, RI, USA) [46, 47]. Briefly, MP’s spatial profile was assessed by measuring MP at 0.25°, 0.5°, 1.0°, and 1.75° of retinal eccentricity, with a reference point located at 7°. The HFP edge effect is assumed in this study. Thus, the 0.25°, 0.5°, 1°, 1.75°, and 7° (the reference point) were obtained using the target diameters: 30-min (0.5°), 1°, 2°, 3.5°, and 2°, respectively. For the 7° target, a 2° diameter disc with its center located 7° from a red fixation point was used.

A detailed description of this technique has been presented previously [48, 49]. MP levels were also measured by dual-wavelength autofluorescence using the Spectralis HRA + OCT Multicolour (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). This method has been described in detail elsewhere [50–52]. MP at 0.25° and 0.5° eccentricities (Densitometer), and total MP volume (Spectralis) are reported in this study.

Serum carotenoid (L and Z) analysis

Non-fasting blood samples were collected from study subjects in 9 mL vacuette tubes each containing a “Z Serum Sep Clot Activator.” Collection tubes were inverted at least five times to ensure thorough mixing of the clot activator. The blood samples were then left to clot for 30 min at room temperature, after which they were centrifuged at 725 g for 10 min in a Gruppe GC 12 centrifuge to separate the serum from the whole blood. Serum sections were then transferred to light-resistant micro tubes and stored at – 80°C until further analysis was necessary. Serum carotenoid measurements were carried out as described previously [19].

Assessment of cognitive function

Cognition was assessed using various validated measurements. Phonemic fluency (the FAS test) was measured by completing as many words as possible, starting with each letter, and allowing a 1-min time limit per letter [47]. A semantic fluency score was also examined using “Animal” as the chosen category, with the subject required to give as many exemplars as possible in 1 min [47]. A battery of tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery [53, 54] (CANTAB, Cambridge Cognition, Cambridge, UK) were used to assess cognitive response in subjects using a computerized software program. These tests required a finger-operated subject response on a touch-screen tablet PC. A set of scripted instructions was provided for each test. The cognition tests were conducted at near distance of approximately 30–40 cm from the subject, and all subjects had near vision of sufficient quality to conduct the cognition tests using the CANTAB device. The actual tests used were as follows: (i) A modified version of the Verbal Recognition Memory task (VRM) was selected to assess verbal learning and memory [47, 48]. In the modified version a free recall format was used instead of a recognition format for the three learning trials, and subsequently both delayed free recall and delayed recognition were evaluated. In this task, the subject was asked to recall as many words as possible after being presented with a list of 12 words, one at a time. This was repeated three times, with scores calculated for free recall for each learning trial, total immediate free recall (sum of the three learning trials), and number of intrusion errors (recalling words that had not been presented). Under the delayed free-recall condition, the subjects were tested on their ability to complete a free recall phase (number of words free recalled and number of intrusion errors). This was followed by a recognition phase in the presence of a matched set of distractor words, and the scores include the number of list words correctly recognized and the number of distractor words incorrectly identified as list words (false positives); (ii) Attention switching task (AST) [53, 55], which is a test of the participant’s ability to switch attention between the direction of an arrow and its location on the screen, while ignoring irrelevant information from interfering or distracting events. This test is designed to measure top-down cognitive control processes involving the prefrontal cortex, and displays an arrow, which can appear on either the right or left side of the screen and can point in either direction. Each trial displays a cue at the top of the screen that indicates whether the subject should press the right or left button according to the “side on which the arrow appeared” or the “direction in which the arrow was pointing”. Some trials also display congruent stimuli (e.g., arrow on the right side of the screen pointing to the right) whereas other trials display incongruent stimuli which require higher cognitive skills (e.g., arrow on the right side of the screen pointing to the left). AST outcome measures include response latencies and error scores that reflect the participant’s attention switching ability and the interference of incongruent task-irrelevant information; (iii) the paired associate learning (PAL) [56], a test which assesses visual memory and new learning. The subject is presented with a set of white boxes, some of which contain a particular pattern, with the subject being tasked with remembering the location of each of the patterns. The difficulty of the test is gradually increased, and if a mistake is made the subject is reminded of the pattern location and is given another opportunity to select the correct box. The test ends when the final stage is completed or if a subject exceeds a specified number of attempts at any given stage. The official CANTAB protocol was followed in the administration of all tests [57].

Statistics

The statistical package IBM SPSS version 21 was used for all analyses. The primary outcome measures were baseline MP, serum L and Z concentrations, and cognitive scores. Relationships among these variables in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and in subjects with early AMD (Group 2) were first investigated using elementary methods, in particular, bivariate correlations and independent samples t-tests. Statistically significant results, identified from the bivariate analyses, were then re-analyzed using general linear models, in order to control for possible confounding variables (such as age, education level, gender, and diet score). The 5% significance level was used throughout all analyses, without adjustment for multiple tests.

Initial examination of the data revealed a very limited range of values for some cognitive variables. This was particularly true for some of the VRM cognitive variables (e.g., VRM Trial 3 recall and VRM Trial 3 intrusion errors). We treated such variables as categorical rather than quantitative, combining adjacent categories to form new “low” and “high” cognitive score categories. Associations between these new variables, and quantitative variables such as MP, were then analyzed using independent samples t-tests, and graphically investigated using box-plots.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the baseline demographic, health and lifestyle, and MP data, while Table 2 presents the cognition data in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and in subjects with early AMD (Group 2) in the CREST trial. As presented in Table 1, there were statistically significant differences between the study groups in terms of age, diet, education level, and gender, and hence we controlled for these where appropriate in all subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic, health and lifestyle, and macular pigment data of the subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and subjects with early AMD (Group 2)

| Variables | Low MP group (n = 105) | AMD group (n = 121) | Sig. |

| Age (years) | 47 ± 12.1 | 65 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.6 ± 4.5 | 28.0 ± 4.5 | 0.020 |

| Exercise (total exercise per week) | 306.4 ± 309.5 | 346.5 ± 390.6 | 0.416 |

| Diet score (Estimated lutein and zeaxanthin intake) | 22.6 ± 13.5 | 26.2 ± 12.1 | 0.034 |

| Serum lutein (μmol/l) | 0.245 ± 0.14 | 0.306 ± 0.20 | 0.01 |

| Serum zeaxanthin (μmol/l) | 0.092 ± 0.06 | 0.105 ± 0.09 | 0.207 |

| Education (highest level %) | <0.001 | ||

| Primary | 1.9 | 14.9 | |

| Secondary | 23.8 | 47.1 | |

| Higher (third level) | 74.3 | 38 | |

| Smoking (%) | 0.101 | ||

| Never smoked | 48.1 | 48.8 | |

| Past smoker | 33.7 | 42.1 | |

| Current smoker | 18.3 | 9.1 | |

| Alcohol (%) | 0.155 | ||

| Never drink | 5.8 | 12.5 | |

| Drink on special occasions | 13.5 | 20 | |

| Drink once or twice a month | 22.1 | 19.2 | |

| Drink once or twice a week | 52.9 | 39.2 | |

| Drink every day | 5.8 | 8.3 | |

| Drink twice a day or more | 0 | 0.8 | |

| Gender (%) | 0.012 | ||

| Male | 49.5 | 33.1 | |

| Female | 50.5 | 66.9 | |

| MP | |||

| MP 0.25 | 0.388 ± 0.11 | 0.751 ± 0.25 | <0.001 |

| MP 0.5 | 0.305 ± 0.12 | 0.626 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

| MP volume | 4189 ± 1758 | 5349 ± 2630 | <0.001 |

Data displayed are mean ± standard deviation for numerical data and percentages for categorical data. Variables, variables analyzed in the study; AMD group, subjects recruited into the study confirmed as having AMD in at least one eye; Low MP group, subjects recruited into the study with MP at 0.25 degrees of eccentricity less than 0.5 optical density units; Sig., the statistical difference (p value) between AMD and low MP subjects assessed using either independent samples t-tests or chi-squared depending on the variable of interest; Body mass index, Measure of body fat based on height and weight; Exercise, total exercise measured as minutes per week engaged in physical or sporting activity; Diet score, estimated dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin; Education, highest level to which subject was educated; Smoking, current smoker (smoked ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime and at least one in the last year), past smoker (smoked ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime and none in past year), or non-smoker (smoked <100 cigarettes in lifetime); Alcohol, as above; MP 0.25, spatial profile of MP measured at 0.25° of retinal eccentricity, with a reference point at 7° (measured using the macular densitometer); MP 0.5, spatial profile of MP measured at 0.5° of retinal eccentricity, with a reference point at 7° (measured using the macular densitometer); MP volume, a volume of MP calculated as MP average times the area under the curve out to 8° eccentricity (measured using the Heidelberg Spectralis ®).

Table 2.

Cognition data of the subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and subjects with early AMD (Group 2)

| Variables | Low MP group (n = 105) | AMD group (n = 121) | Sig. |

| FAS test | 42.4 ± 13.5 | 34.1 ± 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Animal fluency | 21.6 ± 5.8 | 15.5 ± 4.0 | <0.001 |

| VRM Trial 1 recall | 8.2 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| VRM Trial 2 recall | 9.9 ± 1.5 | 8.6 ± 1.9 | <0.001 |

| VRM Trial 3 recall | 10.5 ± 1.9 | 9.7 ± 1.6 | 0.002 |

| VRM total immediate free recall | 28.6 ± 4.3 | 23.4 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| VRM learning slope | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| VRM Trial 1 intrusion errors | 0.09 ± 0.35 | 0.17 ± 0.45 | 0.159 |

| VRM Trial 2 intrusion errors | 0.08 ± 0.31 | 0.10 ± 0.33 | 0.641 |

| VRM Trial 3 intrusion errors | 0.02 ± 0.20 | 0.04 ± 0.24 | 0.471 |

| VRM Delayed Free Recall | 9.4 ± 2.5 | 7.6 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| VRM Delayed Free Recall intrusion errors | 0.09 ± 0.32 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.025 |

| VRM Delayed Recognition total | 23.3 ± 3.5 | 23.1 ± 1.5 | 0.468 |

| VRM Delayed Recognition false positives | 0.09 ± 0.32 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.038 |

| AST Mean Correct Latency | 836.6 ± 197.9 | 1068.2 ± 198.5 | <0.001 |

| AST Congruency Cost | 108.7 ± 98.8 | 168.7 ± 120.8 | <0.001 |

| AST Switch Cost | –117.8 ± 114.2 | –101.0 ± 140.3 | 0.334 |

| AST Percent Correct | 94.3 ± 6.4 | 82.8 ± 16.2 | <0.001 |

| PAL Total Errors | 19.6 ± 23.2 | 49.0 ± 33.1 | <0.001 |

| PAL Total Errors at Stage 6 | 5.8 ± 6.4 | 12.6 ± 10.1 | <0.001 |

| PAL Memory score | 19.5 ± 5.3 | 13.3 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

Data displayed are mean ± standard deviation for numerical data. Variables, variables analyzed in the study; FAS, a phonemic fluency score generated by the total number of words produced for each of the letters F, A, and S in 1 min (high score is preferable); Animal fluency, (semantic fluency score) a semantic fluency score obtained from the number of animals named by the subject in 1 min (high score is preferable); VRM (Verbal Recognition Memory) Trial 1, 2, and 3 recall and total immediate free recall. Subject is asked to recall as many words as possible after being presented with a list of stimuli. This is repeated three times and scores are calculated for each individual trial in addition to a total score, (high score is preferable); VRM learning slope, trial 3 recall – trial 1 recall (high score is preferable); VRM Trial 1, 2, and 3 intrusion errors, number of words recalled that did not appear in the list (low score is preferable); VRM Delayed free recall, number of list words free recalled after a delay (high score is preferable); VRM Delayed free recall intrusion errors, number of words recalled after a delay that did not appear in the list (low score is preferable); VRM Delayed Recognition total, recognition memory of the previous words after a delay period. Subjects are tested on their ability to complete a recognition phase in the presence of a matched set of distractor stimuli and are scored on the total number of correctly identified list words and distractors (high score is preferable); VRM Delayed Recognition false positives, the total number of times that the subject responds “yes” incorrectly to a distractor word (low score is preferable); AST Mean Correct Latency, Attention Switching Task, the algorithm of the latency of response from stimulus appearance to button press. It is a test of the participant’s ability to switch attention between the direction of an arrow and its location on the screen, while ignoring irrelevant information from interfering or distracting events (low score is preferable); AST Congruency Cost, the difference between the algorithm response latency from stimulus appearance to button press of congruent versus incongruent assessed trials. It is calculated by subtracting the algorithm response latency for congruent trials from the algorithm reaction latency for incongruent trials (a positive score indicates that the subject is faster on congruent trials and a negative score indicates that the subject is faster on incongruent trials) Congruent trial = Trial where the arrow was on the same side as the direction it was pointing. Incongruent trial = Trial where the arrow was on one side but pointing in the opposite direction; AST Switch Cost, The difference between the algorithm response latency from stimulus appearance to button press of non-switched versus switched assessed trials. It is calculated by subtracting the algorithm response latency for non-switched trials from the algorithm reaction latency for switched trials. Switched trials = trials where the trial type was Side but the previous trial type was Direction, or the trial type was Direction but the previous trial type was Side. Non-switched trials = trials where the trial type was the same as the previous trial. A positive score indicates that the subject is faster on non-switched trials, and a negative score indicates that the subject is faster on switched trials. AST Percent Correct, percentage of trials, as filtered by the parameters set using available options, for which the trial outcome was a correct response (high score is preferable); PAL Total Errors, Paired Associates Learning (total errors adjusted) measures visual memory and new learning of subjects by assessing the total number of errors across all assessed problems and stages, with an adjustment for each stage not attempted due to previous failure (low score is preferable); PAL Total Errors at Stage 6, Paired Associates Learning (total errors adjusted at the 6 pattern stage) measures the total number of errors made at the 6-pattern stage (when there is a stimulus in each of 6 boxes), with an adjustment for those who have not reached this stage (low score is preferable); PAL Memory score (first trial memory score), the number of patterns correctly located after the first trial, summed across the stages completed (high score is preferable).

Relationship between macular pigment optical density and cognitive scores

a. Subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1)

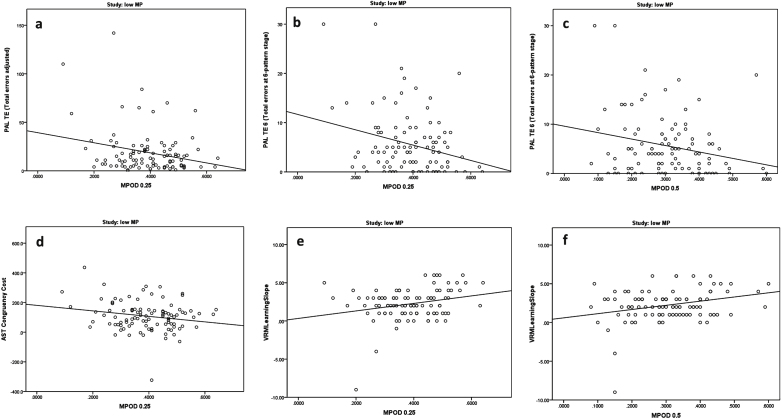

Significant relationships between MP and cognitive scores in the subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) are presented in Table 3 and in Figs. 1 and 2a and b.

Table 3.

Significant correlations between MP and cognitive scores in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and subjects with early AMD (Group 2)

| Low MP group | AMD group | |||||||||||

| Densitometer | Spectralis | Densitometer | Spectralis | |||||||||

| MP 0.25 | MP 0.5 | AF MP vol. | MP 0.25 | MP 0.5 | AF MP vol. | |||||||

| Cognitive test | r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value | r value | p value |

| FAS test | 0.072 | 0.476 | 0.116 | 0.248 | 0.002 | 0.982 | 0.261 | 0.004 | 0.244 | 0.008 | 0.160 | 0.083 |

| Animal fluency | 0.008 | 0.933 | 0.000 | 0.997 | 0.003 | 0.975 | 0.186 | 0.044 | 0.188 | 0.042 | 0.171 | 0.063 |

| AST Congruency Cost | –0.201 | 0.045 | –0.103 | 0.308 | –0.063 | 0.530 | 0.122 | 0.188 | 0.127 | 0.173 | 0.091 | 0.325 |

| AST Percent Correct | 0.004 | 0.971 | –0.004 | 0.972 | 0.091 | 0.364 | 0.214 | 0.020 | 0.200 | 0.030 | 0.111 | 0.230 |

| PAL Total Errors | –0.247 | 0.013 | –0.184 | 0.067 | 0.128 | 0.204 | –0.224 | 0.015 | –0.180 | 0.052 | –0.030 | 0.744 |

| PAL Total Errors Stage 6 | –0.273 | 0.006 | –0.235 | 0.018 | 0.181 | 0.071 | –0.183 | 0.047 | –0.145 | 0.117 | –0.050 | 0.586 |

| VRM Learning Slope | 0.258 | 0.009 | 0.290 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.959 | –0.079 | 0.397 | –0.046 | 0.617 | –0.025 | 0.786 |

MP, macular pigment; AMD group, subjects recruited into the study confirmed as having early AMD in at least one eye; Low MP group, subjects recruited into the study with MP at 0.25 degrees of eccentricity less than 0.5 optical density units; Densitometer, measures MPOD at 0.25 and 0.5 degrees of eccentricity by customized heterochromatic flicker photometry; Spectralis, measures MP volume, a volume of MP calculated as MP average times the area under the curve out to 8 degrees eccentricity. r value, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, is a measure of the strength of the association between the two variables; p value, the statistical significance of the correlation between two variables, with correlations considered statistically significant when p = <0.05; FAS test, a word fluency score generated by the total number of words produced for each of the letters F, A, and S in 1 minute (high score is preferable); Animal fluency, (semantic fluency score) a semantic fluency score obtained from the number of animals named by the subject in 1 minute (high score is preferable); AST Congruency Cost, Attention Switching Task, the difference between the algorithm response latency from stimulus appearance to button press of congruent versus incongruent assessed trials. It is calculated by subtracting the algorithm response latency for congruent trials from the algorithm reaction latency for incongruent trials (a positive score indicates that the subject is faster on congruent trials and a negative score indicates that the subject is faster on incongruent trials); AST Percent Correct, Attention Switching Task, percentage of trials, as filtered by the parameters set using available options, for which the trial outcome was a correct response (high score is preferable); PAL Total Errors, Paired Associates Learning (total errors adjusted) measures visual memory and new learning of subjects by assessing the total number of errors across all assessed problems and stages, with an adjustment for each stage not attempted due to previous failure (low score is preferable); PAL Total Errors at Stage 6, Paired Associates Learning (total errors adjusted at the 6 pattern stage) measures the total number of errors made at the 6-pattern stage (when there is a stimulus in each of 6 boxes), with an adjustment for those who have not reached this stage (low score is preferable); VRM learning slope, trial 3 recall – trial 1 recall (high score is preferable); p values which are significant at the 5% level are highlighted in bold.

Fig.1.

Relationships between macular pigment optical density and cognitive scores in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1).

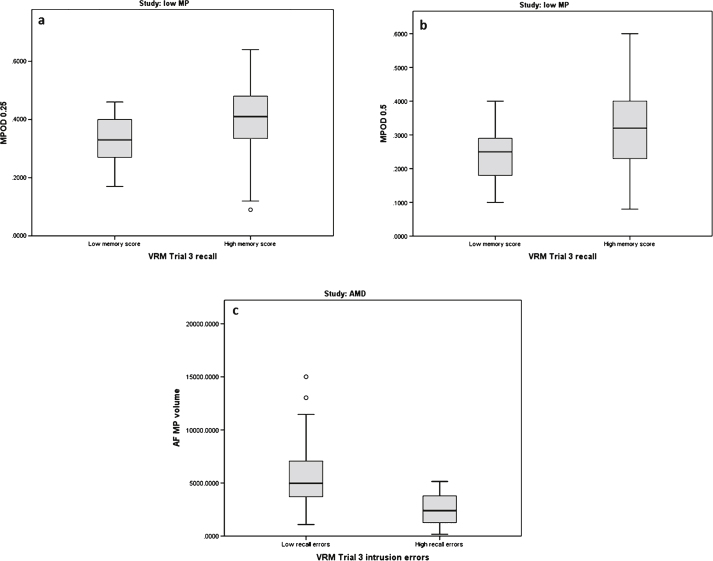

Fig.2.

Boxplots of macular pigment optical density (MPOD 0.25°, 0.5°, and MP volume) and its relationship to Verbal Recognition Memory (VRM) scores in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and in subjects with early AMD (Group 2).

As presented in Table 3, the following cognitive variables correlated negatively and significantly with MP 0.25°: PAL Total Errors, PAL Total Errors at Stage 6, and AST congruency cost; the negative correlations here indicated that higher MP was associated with better cognitive scores in this group. After controlling for age, gender, diet, and education level, using a general linear model, these relationships with MP 0.25° remained significant (p = 0.009 for PAL Total Errors, p = 0.006 for PAL Total Errors at Stage 6, and p = 0.022 for AST congruency cost). In addition, and also as presented in Table 3, the VRM learning slope variable correlated positively and significantly with MP 0.25°, indicating that higher MP was associated with better cognitive scores. The relationship between MP 0.25 and VRM learning slope was, however, no longer statistically significant (p = 0.273) after controlling for age, gender, diet, and education level.

Two cognitive variables in Table 3 were significantly related to MP 0.5°: the first, a negative correlation with PAL Total Errors at Stage 6. Of note, again, the negative correlation indicates that higher MP was associated with better cognitive scores in this group. After controlling for the same demographic variables mentioned above (age, gender, diet, and education level), this correlation remained statistically significant (p = 0.004). The second variable which was significantly related to MP 0.5° was the VRM learning slope variable. The positive correlation here indicated that higher cognitive scores were seen in patients with higher MP levels. The significant relationship between MP 0.5° and VRM learning slope no longer persisted (p = 0.378) after controlling for age, gender, diet, and education level.

As illustrated in the boxplots in Fig. 2a and b, higher MP values at 0.25° and 0.5° were associated with higher memory scores, and hence better cognitive performance for VRM Trial 3 recall (p = 0.014 and p = 0.032, respectively). The relationships between MP 0.25° and 0.5° and VRM Trial 3 recall were no longer significant after controlling for age, gender, diet. and education level (p = 0.360 and p = 0.570, respectively).

b. Subjects with early AMD (Group 2)

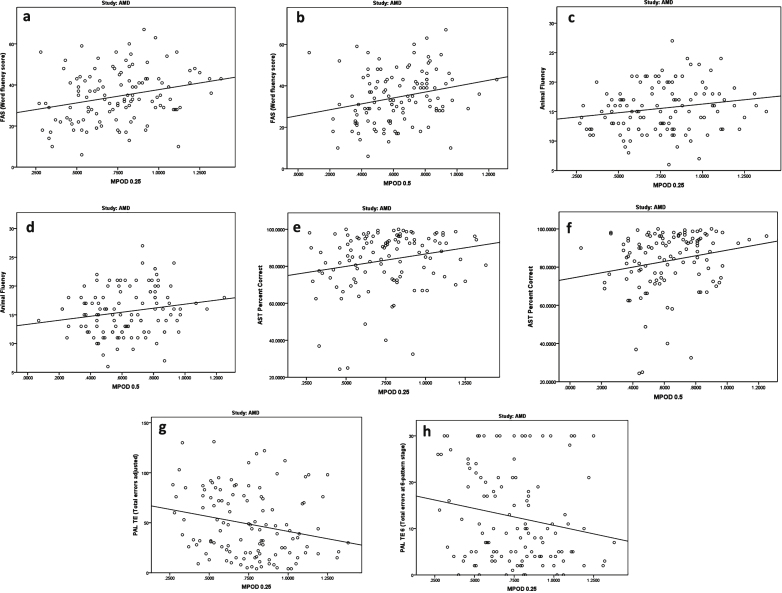

Significant relationships between MP and cognitive scores in the AMD study group (Group 2) are presented in Table 3, Figs. 2c, and 3.

Fig.3.

Relationships between macular pigment optical density and cognitive scores in subjects with early AMD (Group 2).

As seen in Table 3, the following cognitive variables correlated significantly with MP 0.25°: FAS test, animal fluency, AST percent correct, PAL Total Errors, and PAL Total Errors at Stage 6. The correlations with MP 0.25° were positive for FAS test, animal fluency, and AST scores, and negative for both PAL scores. Thus, for each of these tests, higher MP was associated with better cognitive scores. Controlling for age, education level, gender, and diet, using a general linear model, these relationships with MP 0.25° remained significant or nearly significant for the majority of the tests (p = 0.050 for FAS test, p = 0.040 for AST percent correct, p = 0.039 for PAL Total Errors, and p = 0.095 for PAL Total Errors at Stage 6) but the relationship with animal fluency was no longer significant (p = 0.776).

Three cognitive variables in Table 3 correlated significantly with MP 0.5°: FAS test, animal fluency, and AST percent correct; these correlations were positive, indicating that higher MP 0.5° was associated with better cognitive scores. Controlling for age, education level, gender, and diet, using a general linear model, these relationships with MP 0.5° remained significant or nearly significant (p = 0.067 for FAS test, p = 0.030 for AST percent correct), while the relationship with animal fluency was no longer significant (p = 0.386).

As illustrated in the boxplot in Fig. 2c, higher MP volume was associated with lower recall errors, and hence better cognitive performance for VRM Trial 3 intrusion errors (p = 0.016). This relationship remained statistically significant (p = 0.008) after controlling for age, gender, diet, and education level.

Relationship between serum L concentration and cognitive scores

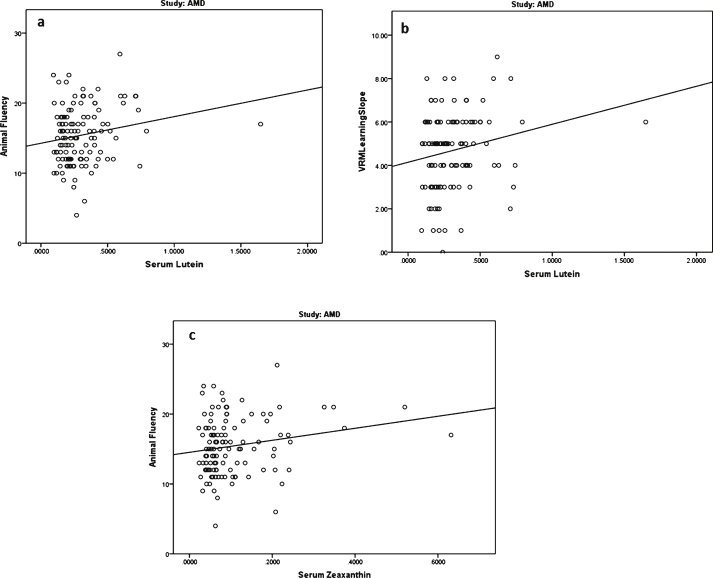

We found two statistically significant relationships between serum L concentrations and cognitive scores, and both were found in the AMD study group (Group 2). The cognitive test scores which correlated with serum L concentrations were animal fluency (p = 0.047) and VRM learning slope (p = 0.031); see Fig. 4a and b. The correlations were positive, indicating that higher serum L is associated with better cognitive performance. The relationships between serum L concentration and animal fluency (p = 0.699) and VRM learning slope (p = 0.254) were no longer statistically significant, after controlling for age, education level, gender, and diet.

Fig.4.

Relationships between serum concentrations of lutein (L) and zeaxanthin (Z) (μmol/l) and cognitive scores in subjects with early AMD (group 2).

Relationship between serum Z concentration and cognitive scores

We found only one statistically significant relationship (p = 0.046) between serum Z concentrations and cognitive scores, and it was again only noted in the AMD study group (Group 2) and for the animal fluency cognitive test; see Fig. 4c. The correlation was positive, indicating that higher serum Z is associated with better cognitive performance. However, the correlation between serum Z and animal fluency was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.773), after controlling for age, education level, gender, and diet.

Relationship between macular pigment optical density and serum L and Z concentrations

a. Subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1)

Serum L concentrations correlated significantly with all measures of MP (MP 0.25°, MP 0.5°, AF MP volume) in this group (p = 0.030, 0.024, <0.001 respectively), while serum Z concentrations correlated significantly with MP volume (p = <0.001). These significant relationships (between L, Z, and MP) all remained after controlling for age, gender, education level, and diet, in this study group.

b. Subjects with early AMD (Group 2)

Serum L concentrations correlated significantly with all measures of MP (MP 0.25°, MP 0.5°, AF MP volume) in the AMD study group (p = 0.034, 0.023, <0.001). Serum Z concentrations also correlated significantly, in this study group, with MP volume (p = 0.003). Controlling for age, gender, education level, and diet in the AMD study group, however, MP at 0.25° (p = 0.356) and 0.5° (p = 0.215) were no longer significantly correlated with serum L concentrations. The significant correlation between MP volume and serum Z became borderline (p = 0.067).

DISCUSSION

This study presents findings on the respective relationships between cognitive function, MP, and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids, in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and in subjects with early AMD (Group 2), all of whom are participants in CREST (a clinical trial designed to study the impact of carotenoid supplementation on vision in patients with AMD and in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP at baseline) [43]. The rationale and motivation for performing the current study relates to the possible role that these carotenoids play in brain health and function. Indeed, in what is becoming an emerging area of scientific research, several recent reviews have discussed the link between the macular carotenoids and cognitive performance [33, 34, 58, 59], and we know that L and Z are found in the human brain [30, 32, 60]. In addition, in non-human primates, it has been shown that carotenoid concentrations in the retina correlate with brain concentrations of these nutrients [61], and that serum concentrations of L and Z correlate with brain carotenoid levels in elderly adults [60]. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated a link between MP and cognitive performance [39–42], and our group has shown that subjects with moderate AD have significantly lower MP when compared to control subjects [19], and, in addition, a follow on study has demonstrated that supplementation with the macular carotenoids significantly increases serum concentrations of L and Z and MP levels in these subjects [35]. However, the current investigation is the first report on the respective relationships between MP (and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids), and cognitive function in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP (Group 1) and in subjects with early AMD (Group 2).

The main finding from this work was that significant correlations exist between MP and cognitive scores in each study group. For example, higher MP levels were associated with better performance in several cognitive tests, including: 1) phonemic fluency, which is primarily dependent on frontal cortex integrity [62]; 2) attention switching, which reflects prefrontal cortex functioning in top down cognitive control processing [63]; 3) visual and verbal memory and learning [64, 65] which involve a variety of brain regions, including anterior medial regions of the prefrontal cortex, lateral parietal/temporal regions, the medial region of the posterior cingulate, and the hippocampus [66].

Of note, our findings are consistent with reports of other investigators; for example, previous work has shown that MP is significantly related to visual - motor performance, i.e., the link between the visual (eye) cue and motor (brain) response of the central nervous system in both older and younger subjects [40, 67]. Moreover, a recent publication found a link between MP and cognitive function in older adults [41]. In that study, where they tested healthy subjects, MP levels were only related to visual-spatial and constructional abilities, while for subjects with mild cognitive impairment, MP levels correlated with a broad range of cognitive measures including visual-spatial and constructional abilities, attention, language ability, and both immediate and delayed memory [41]. A similar finding was also reported in a recent study where MP levels were significantly related to processing speed, recall, verbal learning and fluency, perceptual speed, and better global cognition in a group of older subjects [42]. In addition, a large study in a group of older adults found that lower MP correlated with poor performance on a range of cognitive tests examining executive function, processing speed, prospective memory, and reaction times [39]. Finally, our group has shown that subjects with moderate AD have significantly lower MP when compared to control subjects [19]. Also, and interestingly, in the non-interventional phase of a recent study involving young healthy subjects, a moderate, yet significant, correlation was found between MP and visual processing and neural efficiency, indicating that the relationship between MP and cognitive function is not only present in older populations [67]. In summary, our findings are consistent with these studies, in that similar relationships were seen between MP and cognitive function in both younger (i.e., in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP [Group 1]) and in older subjects (with early AMD [Group 2]). Of importance, our finding that MP is correlated with cognitive performance on tasks with a prominent executive functioning component dependent on the frontal cortex [68, 69] is interesting, given that L and Z are known to be present in high concentrations in this area of the brain [30].

Of note, MP is considered a stable measure of tissue L + Z concentrations and is representative of long term carotenoid intake, as opposed to serum concentrations, which reflect more recent dietary activity [42, 70]. Accordingly, it is reasonable to suggest that MP levels in the retina are representative of L and Z concentrations in the brain, given that this relationship has been demonstrated in non-human primates [71] (L and Z in the retina correlated with L and Z in the cerebellum and to a lesser extent in the occipital cortex, while Z concentrations in the retina correlated with those in the pons and frontal cortex of the brain in rhesus monkeys). Since correlations between MP levels and cognition in the human brain [72] have also been demonstrated, the possibility that MP may be used as a biomarker for brain concentrations of the carotenoids and, therefore, by extension, cognition, is plausible and provocative.

Previous studies have also shown that serum L and Z concentrations are related to cognitive function in older adults [60, 73, 74], and that serum L and Z levels are depleted in subjects with MCI [36] and with AD [75, 76]. However, some cognitive scores, such as verbal fluency, are known to be related also to age and education [36] and these variables, in turn, are related to diet. Of note, there is also evidence that L and Z serum concentrations are related to age, education, and diet [77–79]. With respect to the relationship between serum carotenoids and cognitive function in our study, we found few significant correlations. Indeed, and only for the AMD subjects (Group 2), serum L and Z concentrations correlated significantly with semantic (animal) fluency cognitive scores, a task that relies predominantly on temporal lobe functioning [62], and this observation is consistent with the work of others [42], while serum L concentrations also correlated significantly with VRM learning slope scores in the same group, this test indicating the learning ability of the subjects [66]. However, in contrast to our findings for MP, relationships between these cognitive scores and serum L or Z, were not statistically significant when we controlled for age, education, and diet.

This, in conjunction with the paucity of relationships, in our study, between serum concentrations of L and Z and the remaining cognitive tests, given the many relationships observed between MP and the same cognitive tests, suggests that retinal tissue concentrations of these antioxidants represent a more valid and valuable biomarker of brain concentrations of these carotenoids than their respective serum levels. Indeed, this superior suitability of retinal tissue concentrations was suggested in a recent letter by Hammond [80], in which the author highlights, in relation to a previous study [81], how plasma lutein levels were unrelated to cognitive enhancement in children. However, it is worth noting that coarse cognitive assessments were used.

The circulatory system delivers carotenoids to target tissue, and increasing concentrations of circulating carotenoids have been shown to attenuate the adverse effects of amyloid-β peptide in human blood [82]. This peptide impairs red blood cells (RBCs) through phospholipid peroxidation, thereby reducing oxygen delivery to the brain, and a consequential increased susceptibility to AD [82]. This attenuation of amyloid-β-induced RBC damage following treatment of RBCs with xanthophylls, including L, is consistent with a protective role for these carotenoids in terms of risk for AD [82, 83].

We have confirmed previously observed positive relationships between MP and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids. Serum L concentrations correlated significantly with all measures of MP in each study group, whereas serum concentrations of Z correlated significantly with MP volume in each study group, and these findings are consistent with previous reports [27, 29, 78, 84, 85].

Taken together, the results of our study suggest that MP levels may indeed be a reliable biomarker of cognition in humans. Given that cognitive decline, and diseases associated with cognitive decline, are age-related and progressive (characteristics shared with AMD), early intervention with formulations containing the macular carotenoids, shown to be beneficial in AMD, may offer some advantage in terms of amelioration of the natural course of cognitive decline associated with either aging or AD. Indeed a recent study by our group has demonstrated that AD patients, as well as normal control patients, respond to carotenoid supplementation, in terms of MP augmentation [35].

Several recent publications suggest health benefits associated with long-term use of antioxidant supplements, including L [58, 86, 87], and this should be considered (in conjunction with other important lifestyle variables) for healthy aging [77, 88, 89]. A recent study, for example, suggests a dual strategy for reducing risk for, and progression of, diseases associated with cognitive decline, such as AD; a “primary prevention” approach refers to modification of those risk factors amenable to intervention, in conjunction with screening to identify preclinical disease prior to damage mediated by amyloid plaque deposition [90]. In a recent letter authored by a panel of experts at the G8 dementia summit [91], governments of those nations were encouraged to prioritize prevention of dementia as a public health measure.

The limitations of this study include the L/Z screener, which may be considered relatively crude, the measurement of non-fasting patient serum samples for L and Z serum concentrations, the necessity to simplify the cognitive variables VRM Trial 3 recall and VRM Trial 3 intrusion errors into low and high categories for analysis, and perhaps most significantly the low correlation between results obtained from the Densitometer and the Spectralis. This lack of correlation is surprising as a previous report by our group suggested that measures of MP obtained from the Densitometer and Spectralis were highly correlated, at least in subjects without ocular disease [92]. For AMD subjects, concordance information is not currently available but is in fact under investigation by our group. MP measurement has, however, previously been extensively validated using the Densitometer [47, 93], including a study in AMD subjects [49]. An absence of validation studies for physical MP measurement methods such as fundus autofluorescence measured by the Spectralis has been noted by other groups [94], whereas the repeatability of the Densitometer when using the customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP) technique was confirmed previously [95]. It is therefore our view that cHFP, an optimized form of HFP, represents the best and most dependable reference standard to which other MP measuring techniques should be compared. Taking this into consideration, it is perhaps encouraging that most of the correlations seen in our study in relation to MP and cognition were with MP 0.25 (Table 3). This may be considered important as central eccentricities were previously found to be those where concordance was strongest between the Densitometer and Spectralis, while agreements diminished with increasing eccentricities [92]. Central MP would thus perhaps be more likely to play a key role in contributing to the correlations with cognition seen in this study. It is also worth noting that while indeed absent in general, there was one correlation evident between MP volume and VRM (Fig. 2c). The cross sectional design of the study may also be considered a possible limitation.

In conclusion, we have shown that MP levels correlate with performance on a range of cognitive tests in subjects free of retinal disease with low MP and in subjects afflicted with AMD, and serum concentrations of MP’s constituent carotenoids were related to verbal fluency (but this latter association was lost when age, education and diet were controlled for). Accordingly, it is reasonable to hypothesize that MP is a valid biomarker for cognitive function, and its role in this regard warrants further exploration for the wider population. Finally, the possibility that supplementation with MP’s constituent carotenoids may delay the onset or ameliorate the progression of cognitive decline cannot be ignored.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The CREST study was funded by a starter grant from the European Research Council (ERC); reference number: 281096. We thank the CREST participants, and we also acknowledge Cambridge Cognition, UK, for guidance with respect to the assessment of cognitive function. We would also like to thank the Reading Centre, Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, UK, for retinal photograph grading. We thank Prof. Elizabeth Johnson from Tufts University, USA, for permission to use the “L/Z screener” for estimating dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin in this study.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/15-0199r2).

REFERENCES

- 1.Meagher KA, Thurnham DI, Beatty S, Howard AN, Connolly E, Cummins W, Nolan JM. Serum response to supplemental macular carotenoids in subjects with and without age-related macular degeneration. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:289–300. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512004837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bone RA, Landrum JT, Friedes LM, Gomez CM, Kilburn MD, Menendez E, Vidal I, Wang WL. Distribution of lutein and zeaxanthin stereoisomers in the human retina. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:211–218. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khachik F, Spangler CJ, Smith JC, Jr, Canfield LM, Steck A, Pfander H. Identification, quantification, and relative concentrations of carotenoids and their metabolites in human milk and serum. Anal Chem. 1997;69:1873–1881. doi: 10.1021/ac961085i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widomska J, Subczynski WK. Why has nature chosen lutein and zeaxanthin to protect the retina? J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;5:326. doi: 10.4172/2155-9570.1000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beatty S, Koh HH, Henson D, Boulton M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevithick-Sutton CC, Foote CS, Collins M, Trevithick JR. The retinal carotenoids zeaxanthin and lutein scavenge superoxide and hydroxyl radicals: A chemiluminescence and ESR study. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1127–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pintea A, Socaciu C, Rugina DO, Pop R, Bunea A. Xanthophylls protect against induced oxidation in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Food Compost Anal. 2011;26:830–836. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junghans A, Sies H, Stahl W. Macular pigments lutein and zeaxanthin as blue light filters studied in liposomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;391:160–164. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bressler NM. Age-related macular degeneration is the leading cause of blindness. JAMA. 2004;291:1900–1901. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.15.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loane E, Kelliher C, Beatty S, Nolan JM. The rationale and evidence base for a protective role of macular pigment in age-related maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1163–1168. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.135566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chew E, The AREDS2 Study Group Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2005–2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beatty S, Chakravarthy U, Nolan JM, Muldrew KA, Woodside JV, Denny F, Stevenson MR. Secondary outcomes in a clinical trial of carotenoids with coantioxidants versus placebo in early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabour-Pickett S, Beatty S, Connolly E, Loughman J, Stack J, Howard A, Klein R, Klein BE, Meuer SM, Myers CE, Akuffo KO, Nolan JM. Supplementation with three different macular carotenoid formulations in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2014;34:1757–1766. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Jiang C, Zhang Y, Gong Y, Chen X, Zhang M. Role of lutein supplementation in the management of age-related macular degeneration: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ophthalmic Res. 2014;52:198–205. doi: 10.1159/000363327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang YM, Yan SF, Ma L, Zou ZY, Xu XR, Dou HL, Lin XM. Serum and macular responses to multiple xanthophyll supplements in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Nutrition. 2013;29:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weigert G, Kaya S, Pemp B, Sacu S, Lasta M, Werkmeister RM, Dragostinoff N, Simader C, Garhofer G, Schmidt-Erfurth U, Schmetterer L. Effects of lutein supplementation on macular pigment optical density and visual acuity in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:8174–8178. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma L, Yan SF, Huang YM, Lu XR, Qian F, Pang HL, Xu XR, Zou ZY, Dong PC, Xiao X, Wang X, Sun TT, Dou HL, Lin XM. Effect of lutein and zeaxanthin on macular pigment and visual function in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2290–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray IJ, Makridaki M, van der Veen RL, Carden D, Parry NR, Berendschot TT. Lutein supplementation over a one-year period in early AMD might have a mild beneficial effect on visual acuity: The CLEAR study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:1781–1788. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolan JM, Loskutova E, Howard AN, Moran R, Mulcahy R, Stack J, Bolger M, Dennison J, Akuffo KO, Owens N, Thurnham DI, Beatty S. Macular pigment, visual function, and macular disease among subjects with Alzheimer’s disease: An exploratory study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:1191–1202. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loughman J, Nolan JM, Howard AN, Connolly E, Meagher K, Beatty S. The impact of macular pigment augmentation on visual performance using different carotenoid formulations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:7871–7880. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snodderly DM, Brown PK, Delori FC, Auran JD. The macular pigment. 1. Absorbance spectra, localization, and discrimination from other yellow pigments in primate retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:660–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loskutova E, Nolan J, Howard A, Beatty S. Macular pigment and its contribution to vision. Nutrients. 2013;5:1962–1969. doi: 10.3390/nu5061962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond BR, Fletcher LM, Roos F, Wittwer J, Schalch W. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on photostress recovery, glare disability, and chromatic contrast. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:8583–8589. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu R, Wang T, Zhang B, Qin L, Wu C, Li Q, Ma L. Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation and association with visual function in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:252–258. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobbs RP, Bernstein PS. Nutrient supplementation for age-related macular degeneration, cataract, and dry eye. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9:487–493. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.150829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray IJ, Makridaki M, van der Veen RL, Carden D, Parry NR, Berendschot TT. Lutein supplementation over a one-year period in early AMD might have a mild beneficial effect on visual acuity: The CLEAR study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:1781–1788. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly EE, Beatty S, Loughman J, Howard AN, Louw MS, Nolan JM. Supplementation with all three macular carotenoids: Response, stability, and safety. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9207–9217. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolan JM, Stringham JM, Beatty S, Snodderly DM. Spatial profile of macular pigment and its relationship to foveal architecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2134–2142. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thurnham DI, Nolan JM, Howard AN, Beatty S. Macular response to supplementation with differing xanthophyll formulations in subjects with and without age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;253(8):1231–1243. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craft NE, Haitema TB, Garnett KM, Fitch KA, Dorey CK. Carotenoid, tocopherol, and retinol concentrations in elderly human brain. J Nutr Health Aging. 2004;8:156–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vishwanathan R, Neuringer M, Snodderly DM, Schalch W, Johnson EJ. Macular lutein and zeaxanthin are related to brain lutein and zeaxanthin in primates. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:21–29. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vishwanathan R, Kuchan MJ, Sen S, Johnson EJ. Lutein and preterm infants with decreased concentrations of brain carotenoids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:659–665. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson EJ. A possible role for lutein and zeaxanthin in cognitive function in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1161S–1165S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crichton GE, Bryan J, Murphy KJ. Dietary antioxidants, cognitive function and dementia–a systematic review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2013;68:279–292. doi: 10.1007/s11130-013-0370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolan JM, Loskutova E, Howard A, Mulcahy R, Moran R, Stack J, Bolger M, Coen RF, Dennison J, Akuffo KO, Owens N, Power R, Thurnham D, Beatty S. The impact of supplemental macular carotenoids in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized clinical trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:1157–1169. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rinaldi P, Polidori MC, Metastasio A, Mariani E, Mattioli P, Cherubini A, Catani M, Cecchetti R, Senin U, Mecocci P. Plasma antioxidants are similarly depleted in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:915–919. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W, Shinto L, Connor WE, Quinn JF. Nutritional biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: The association between carotenoids, n-3 fatty acids, and dementia severity. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13:31–38. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson EJ, McDonald K, Caldarella SM, Chung HY, Troen AM, Snodderly DM. Cognitive findings of an exploratory trial of docosahexaenoic acid and lutein supplementation in older women. Nutr Neurosci. 2008;11:75–83. doi: 10.1179/147683008X301450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feeney J, Finucane C, Savva GM, Cronin H, Beatty S, Nolan JM, Kenny RA. Low macular pigment optical density is associated with lower cognitive performance in a large, population-based sample of older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2449–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renzi LM, Bovier ER, Hammond BR., Jr A role for the macular carotenoids in visual motor response. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:262–268. doi: 10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Renzi LM, Dengler MJ, Puente A, Miller LS, Hammond BR., Jr Relationships between macular pigment optical density and cognitive function in unimpaired and mildly cognitively impaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:1695–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vishwanathan R, Iannaccone A, Scott TM, Kritchevsky SB, Jennings BJ, Carboni G, Forma G, Satterfield S, Harris T, Johnson KC, Schalch W, Renzi LM, Rosano C, Johnson EJ. Macular pigment optical density is related to cognitive function in older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:271–275. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akuffo KO, Beatty S, Stack J, Dennison J, O’Regan S, Meagher KA, Peto T, Nolan J. Central Retinal Enrichment Supplementation Trials (CREST): Design and methodology of the CREST randomized controlled trials. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21:111–123. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2014.888085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nolan JM, Loughman J, Akkali MC, Stack J, Scanlon G, Davison P, Beatty S. The impact of macular pigment augmentation on visual performance in normal subjects: COMPASS. Vision Res. 2011;51:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis MD, Gangnon RE, Lee LY, Hubbard LD, Klein BE, Klein R, Ferris FL, Bressler SB, Milton RC. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS Report No. 17. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1484–1498. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wooten BR, Hammond BR, Land RI, Snodderly DM. A practical method for measuring macular pigment optical density. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2481–2489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wooten BR, Hammond BR. Spectral absorbance and spatial distribution of macular pigment using heterochromatic flicker photometry. Optometry Vis Sci. 2005;82:378–386. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000162654.32112.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loane E, Stack J, Beatty S, Nolan JM. Measurement of macular pigment optical density using two different heterochromatic flicker photometers. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:555–564. doi: 10.1080/02713680701418405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stringham JM, Hammond BR, Nolan JM, Wooten BR, Mammen A, Smollon W, Snodderly DM. The utility of using customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP) to measure macular pigment in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delori FC, Goger DG, Hammond BR, Snodderly DM, Burns SA. Macular pigment density measured by autofluorescence spectrometry: Comparison with reflectometry and heterochromatic flicker photometry. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2001;18:1212–1230. doi: 10.1364/josaa.18.001212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wustemeyer H, Jahn C, Nestler A, Barth T, Wolf S. A new instrument for the quantification of macular pigment density: First results in patients with AMD and healthy subjects. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:666–671. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trieschmann M, Heimes B, Hense HW, Pauleikhoff D. Macular pigment optical density measurement in autofluorescence imaging: Comparison of one- and two-wavelength methods. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:1565–1574. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robbins TW, James M, Owen AM, Sahakian BJ, McInnes L, Rabbitt P. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB): A factor analytic study of a large sample of normal elderly volunteers. Dementia. 1994;5:266–281. doi: 10.1159/000106735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wild K, Howieson D, Webbe F, Seelye A, Kaye J. Status of computerized cognitive testing in aging: A systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahakian BJ, Downes JJ, Eagger S, Evenden JL, Levy R, Philpot MP, Roberts AC, Robbins TW. Sparing of attentional relative to mnemonic function in a subgroup of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:1197–1213. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90055-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:674–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cognition Limited (2012) CANTAB Eclipse Test Administration Guide, Cambridge Cognition Limited, Cambridge, UK

- 58.Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Ducros V, Jeandel C, Julia C, Hercberg S, Galan P. Carotenoid-rich dietary patterns during midlife and subsequent cognitive function. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:915–923. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rafnsson SB, Dilis V, Trichopoulou A. Antioxidant nutrients and age-related cognitive decline: A systematic review of population-based cohort studies. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:1553–1567. doi: 10.1007/s00394-013-0541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson EJ, Vishwanathan R, Johnson MA, Hausman DB, Davey A, Scott TM, Green RC, Miller LS, Gearing M, Woodard J, Nelson PT, Chung HY, Schalch W, Wittwer J, Poon LW. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:951786. doi: 10.1155/2013/951786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vishwanathan R, Neuringer M, Snodderly DM, Schalch W, Johnson EJ. Macular lutein and zeaxanthin are related to brain lutein and zeaxanthin in primates. Nutr Neurosci. 2013;16:21–29. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baldo JV, Schwartz S, Wilkins D, Dronkers NF. Role of frontal versus temporal cortex in verbal fluency as revealed by voxel-based lesion symptom mapping. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:896–900. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706061078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richter FR, Yeung N. Corresponding influences of top-down control on task switching and long-term memory. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove) 2015;68:1124–1147. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2014.976579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Juncos-Rabadan O, Pereiro AX, Facal D, Reboredo A, Lojo-Seoane C. Do the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery episodic memory measures discriminate amnestic mild cognitive impairment? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:602–609. doi: 10.1002/gps.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Junkkila J, Oja S, Laine M, Karrasch M. Applicability of the CANTAB-PAL computerized memory test in identifying amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;34:83–89. doi: 10.1159/000342116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yonelinas AP, Otten LJ, Shaw KN, Rugg MD. Separating the brain regions involved in recollection and familiarity in recognition memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3002–3008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5295-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bovier ER, Renzi LM, Hammond BR. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on neural processing speed and efficiency. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith EE, Jonides J. Storage and executive processes in the frontal lobes. Science. 1999;283:1657–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stuss DT. Traumatic brain injury: Relation to executive dysfunction and the frontal lobes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:584–589. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834c7eb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nolan JM, Stack J, Mellerio J, Godhinio M, O’Donovan O, Beatty S. Monthly consistency of macular pigment optical density and serum concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31:199–213. doi: 10.1080/02713680500514677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vishwanathan R, Neuringer M, Snodderly DM, Schalch W, Johnson EJ. Macular lutein and zeaxanthin are related to brain lutein and zeaxanthin in primates. Nutr Neurosci. 2012;16:21–29. doi: 10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson EJ, Vishwanathan R, Johnson MA, Hausman DB, Davey A, Scott TM, Green RC, Miller LS, Gearing M, Woodard J, Nelson PT, Chung HY, Schalch W, Wittwer J, Poon LW. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J Aging Res. 2013;2013:951786. doi: 10.1155/2013/951786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dias IH, Polidori MC, Li L, Weber D, Stahl W, Nelles G, Grune T, Griffiths HR. Plasma levels of HDL and carotenoids are lower in dementia patients with vascular comorbidities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40:399–408. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akbaraly NT, Faure H, Gourlet V, Favier A, Berr C. Plasma carotenoid levels and cognitive performance in an elderly population: Results of the EVA Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:308–316. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mecocci P, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Ingegni T, Mattioli P, Catani M, Rinaldi P, Cecchetti R, Stahl W, Senin U, Beal MF. Lymphocyte oxidative DNA damage and plasma antioxidants in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:794–798. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.5.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kiko T, Nakagawa K, Tsuduki T, Suzuki T, Arai H, Miyazawa T. Significance of lutein in red blood cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;28:593–600. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nolan JM, Feeney J, Kenny RA, Cronin H, O’Regan C, Savva GM, Loughman J, Finucane C, Connolly E, Meagher K, Beatty S. Education is positively associated with macular pigment: The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:7855–7861. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nolan JM, Stack J, O’Connell E, Beatty S. The relationships between macular pigment optical density and its constituent carotenoids in diet and serum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:571–582. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nolan JM, Stack J, O’ DO, Loane E, Beatty S. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy are associated with a relative lack of macular pigment. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hammond BR. Lutein and cognition in children. J Nutr Sci. 2014;3:1–2. doi: 10.1017/jns.2014.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mulder KA, Innis SM, Rasmussen BF, Wu BT, Richardson KJ, Hasman D. Plasma lutein concentrations are related to dietary intake, but unrelated to dietary saturated fat or cognition in young children. J Nutr Sci. 2014;3:e11. doi: 10.1017/jns.2014.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakagawa K, Kiko T, Miyazawa T, Sookwong P, Tsuduki T, Satoh A, Miyazawa T. Amyloid beta-induced erythrocytic damage and its attenuation by carotenoids. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Katayama S, Ogawa H, Nakamura S. Apricot carotenoids possess potent anti-amyloidogenic activity in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:12691–12696. doi: 10.1021/jf203654c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Connolly EE, Beatty S, Thurnham DI, Loughman J, Howard AN, Stack J, Nolan JM. Augmentation of macular pigment following supplementation with all three macular carotenoids: An exploratory study. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:335–351. doi: 10.3109/02713680903521951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beatty S, Nolan J, Kavanagh H, O’Donovan O. Macular pigment optical density and its relationship with serum and dietary levels of lutein and zeaxanthin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen K, Zhang X, Wei XP, Qu P, Liu YX, Li TY. Antioxidant vitamin status during pregnancy in relation to cognitive development in the first two years of life. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson EJ. Role of lutein and zeaxanthin in visual and cognitive function throughout the lifespan. Nutr Rev. 2014;72:605–612. doi: 10.1111/nure.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Flicker L. Modifiable lifestyle risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:803–811. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]