Abstract

Background

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2) is a serine protease inhibitor that exerts multiple physiological and patho-physiological activities involving the modulation of coagulation, angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and apoptosis. In previous studies we reported a novel role of human TFPI-2 in innate immunity by serving as a precursor for host defense peptides. Here we employed a number of TFPI-2 derived peptides from different vertebrate species and found that their antibacterial activity is evolutionary conserved although the amino acid sequence is not well conserved. We further studied the theraputic potential of one selected TFPI-2 derived peptide (mouse) in a murine sepsis model.

Results

Hydrophobicity and net charge of many peptides play a important role in their host defence to invading bacterial pathogens. In vertebrates, the C-terminal portion of TFPI-2 consists of a highly conserved cluster of positively charged amino acids which may point to an antimicrobial activity. Thus a number of selected C-terminal TFPI-2 derived peptides from different species were synthesized and it was found that all of them exert antimicrobial activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa. The peptide-mediated killing of E. coli was enhanced in human plasma, suggesting an involvement of the classical pathway of the complement. Under in vitro conditions the peptides displayed anti-coagulant activity by modulating the intrinsic pathway of coagulation and in vivo treatment with the mouse derived VKG24 peptide protects mice from an otherwise lethal LPS shock model.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the evolutionary conserved C-terminal part of TFPI-2 is an interesting agent for the development of novel antimicrobial therapies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-016-0750-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: TFPI-2, Peptide, Complement, Vertebrates, Antimicrobial, Coagulation, Sepsis, Evolution

Background

In response to pathogenic microorganisms, host organisms have evolved a diverse range of defense mechanisms, starting from simple mechanical barriers to complex immune systems. In these processes, blood coagulation, complement cascades and antimicrobial peptides are central to host defense and many components of these systems are evolutionary conserved [1]. The crosstalk between the coagulation and complement systems is essential for the clearance of the infection. Together they have a dual role of immobilization and destruction of invading bacteria in addition to preventing the loss of body fluids. Coagulation factors, apart from their primary role of maintaining hemostasis, are also involved in killing of bacteria and immunomodulation, such as thrombin [2], kininogen [3], protein C inhibitor [4], fibrinogen [5, 6], antithrombin [7], TFPI-1 [8], and TFPI-2 [9, 10]. These proteins may explore their activities either as intact molecules or after proteolysis. Often they execute their host defense functions by killing the intruder or by triggering immunomodulatory reactions. Many well-characterized antimicrobial peptides have recently been found to exhibit also multifaceted immunomodulatory activities, such as reported for LL-37 [11, 12] and some antimicrobial peptides have been described to be involved in angiogenesis, chemotaxis, and wound-healing [11]. These biological properties suggest that host defense peptides may have a clinical potential also in disorders where targeting of inflammatory pathways is beneficial, such as in sepsis [11, 13].

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI-2) consists of a highly negatively charged N-terminal region, three tandemly linked Kunitz-type domains, and a highly positively charged C-terminus [14, 15]. The molecule is synthesized and secreted by many cells, including skin fibroblasts, endothelial cells (ECs), smooth muscle cells (SMCs), dermal fibroblasts, keratinocytes, monocytes, macrophages and syncytiotrophoblasts [16, 17]. In vitro, TFPI-2 is a weak inhibitor of coagulation induced by the TF-VII complex, while it targets a wide range of proteases such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, plasmin, MMPs, factor XIa and plasma kallikrein [18, 19]. Stimulation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with inflammatory mediators such as PMA, LPS, or TNF-α significantly increases TFPI-2 expression [17]. Analogously, in a murine model, TFPI-2 expression is dramatically upregulated in the liver upon LPS stimulation [20]. Notably, it has been shown that proteases such as ADAMTS1, plasmin and thrombin can process TFPI-2 at its C-terminal end in in vitro experiments [21]. We previously reported an undisclosed host defense function of the C-terminal region of TFPI-2 [9, 10]. TFPI-2 as well as the C-terminal peptides of the molecule were detected in wounds from patients and were found in complex with the bacteria and fibrin. Correspondingly, human TFPI-2 was degraded in vitro by human neutrophil elastase, leading to the generation of C-terminal TFPI-2 fragments. These fragments were then found to bind to various bacterial surfaces, kill gram-negative bacteria, through membrane lysis, and boost complement activation, including formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) and antimicrobial C3a. In a therapeutic context, the peptide significantly reduced mortality either as a monotherapy, or in combination with ceftazidime E. coli and P. aeruginosa sepsis models. We therefore hypothesized that TFPI-2 C-terminal derived peptides may have an important function in the host defense to infection, thus they may be interesting agents for drug development.

Results

Phylogenetic and sequence analysis of the TFPI-2 C-terminal part from different species

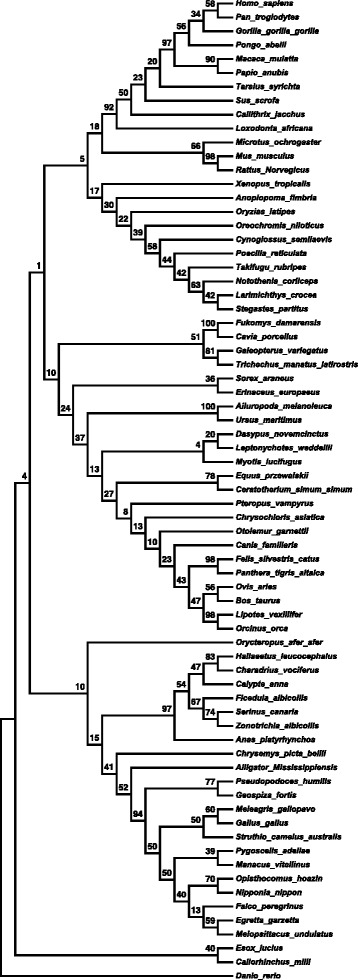

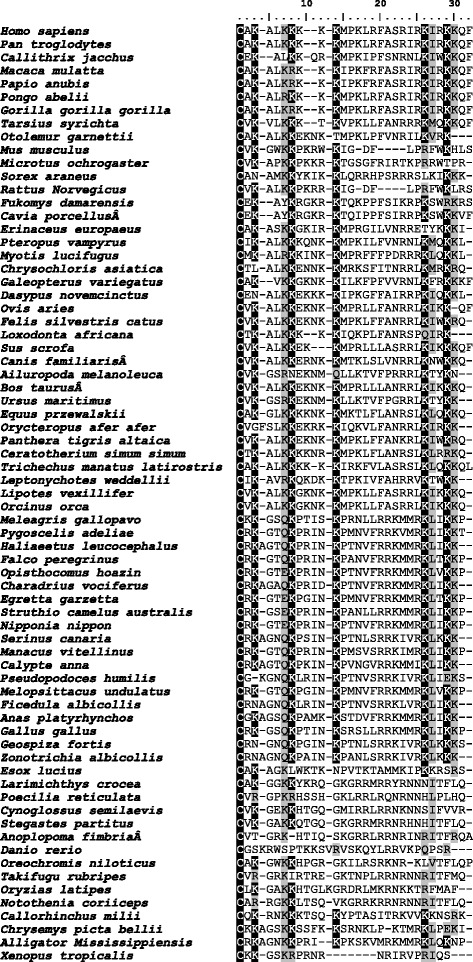

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with C-terminal TFPI-2 sequences from 72 vertebrate organisms, using neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap repeats, resulting in distinct groups (Fig. 1). The remainder of TFPI-2 and full length protein are more conserved than the C-terminal region, at first suggesting that the C-terminal region has not been under evolutionary pressure (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Even though the TFPI-2 amino acid length varies among the species, many other conserved regions were observed among the species (data not shown). Interestingly, the multiple sequence alignment of the C-terminal antimicrobial peptide region is not fully conserved (Fig. 2). Importantly however, even though the C-terminal region was not well conserved, the net positive charge is preserved, with a charge ranging from +7 to +14 (Table 1). This suggests an important role of the charge and points towards putative antimicrobial activity where charge rather than the exact amino acid sequence is essential.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of the C-terminal region of TFPI-2 from vertebrates. Phylogenetic tree from 72 vertebrate TFPI-2 species was constructed using Neighbour-Joining tree with 1000 bootstrap replications on MEGA6

Fig. 2.

Sequence homology of the C-terminal region of TFPI-2. ClustalW multiple sequence alignment of TFPI-2 where identical and similar amino acids in all sequences are highlighted in black and grey shaded, respectively

Table 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of vertebrate TFPI-2 C-terminal region showing identical and similar amino acids

| Entry & name | Latin & name | English & name | Protein & sequence | Net & charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAMMALS | ||||

| P48307 | Homo sapiens | Human | CAKALKKKKKMPKLRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| H2QUX8 | Pan troglodytes | Chimpanzee | CAKALKKKKKMPKLRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| U3ENJ1 | Callithrix jacchus | White-tufted-ear marmoset | CEKALKKQRKMPKIPFSNRNLKIWKKQF | 9 |

| F7CWN2 | Macaca mulatta | Rhesus macaque | CAKALKRKKKIPKFRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| XP_003896360.1 | Papio anubis | Olive baboon | CAKALKRKKKIPKFRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| H2PMX0 | Pongo abelii | Sumatran orangutan | CAKALRKKKKMPKLRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| G3QPC8 | Gorilla gorilla gorilla | Western lowland gorilla | CAKALKRKKKMPKLRFASRIRKIRKKQF | 14 |

| XP_008067041.1 | Tarsius syrichta | Philippine tarsier | CVKVLKKKTKVPKLLFANRRRKMQKKQF | 12 |

| H0XT57 | Otolemur garnettii | Small-eared galago | CAKALKKEKNKTMPKLPFVNRILKVRK | 9 |

| O35536 | Mus musculus | Mouse | CVKGWKKPKRWKIGDFLPRFWKHLS | 7 |

| XP_005363735.1 | Microtus ochrogaster | Prairie Vole | CVKAPKKPKKRKTGSGFRIRTKPRRWTP | 12 |

| XP_004602345.1 | Sorex araneus | European shrew | CANAMKKYKIKKLQRRHPSRRRSLKIKK | 13 |

| EDL84392.1 | Rattus Norvegicus | Brown Rat | CVKALKKPKRRKIGDFLPRFWKLRS | 9 |

| XP_010601797.1 | Fukomys damarensis | Damaraland Mole Rat | CEKAYKRGKRKTQKPPFSIKRPKSWRKR | 12 |

| H0VU83 | Cavia porcellus | Guinea pig | CEKAYKRGKRKTQIPPFSIRRPKSWKKV | 10 |

| XP_007522577.1 | Erinaceus europaeus | Western European Hedgehog | CAKASKKGKIRKMPRGILVNRRETYKKK | 11 |

| XP_011361893.1 | Pteropus vampyrus | Large Flying Fox | CIKALKKKQNKKMPKILFVNRNLKMQKK | 11 |

| G1PX03 | Myotis lucifugus | Little brown bat | CMKALRKKINKKMPRFFFPDRRRKLQKK | 12 |

| XP_006834353.1 | Chrysochloris asiatica | Cape Golden Mole | CTLALKKENNKKMRKSFITNRRLKMRKR | 11 |

| XP_008569808.1 | Galeopterus variegatus | Sunda flying lemur | CAKVKKGKNKKILKFPFVVRNLKFRKKK | 13 |

| XP_004475751.1 | Dasypus novemcinctus | Nine-banded Armadillo | CENALKKEKKKKIPKGFFAIRRPKIQKK | 10 |

| W5NS10 | Ovis aries | Sheep | CVKALKKEKNKKMPRLLFANRRLKIKKQ | 11 |

| M3X7K4 | Felis silvestris catus | Cat | CVKALKKEKNKKMPKLFFANRRLKIWKR | 11 |

| G3THG9 | Loxodonta africana | African elephant | CTKALKKKKKIQKPLFANRSPQIRK | 10 |

| F1SFC1 | Sus scrofa | Pig | CVKALKKEKKMPRLLLASRRLKIKKKQF | 11 |

| E2RBF0 | Canis familiaris | Dog | CVKALKKERNKKMTKLSLVNRRLKNWKK | 11 |

| G1MHA9 | Ailuropoda melanoleuca | Giant panda | CVKGSRNEKNMQLLKTVFPRRRLKTYKN | 8 |

| Q7YRQ8 | Bos taurus | Bovine | CVKALKKEKNKKMPRLLLANRRLKIKKK | 12 |

| XP_008684473.1 | Ursus maritimus | Polar bear | CVKGSRKEKNMKLLKTVFPGRRLKTYKK | 10 |

| XP_008542988.1 | Equus przewalskii | Przewalski’s horse | CAKGLKKKKNKKMKTLFLANRSLKLQKK | 12 |

| XP_007938042.1 | Orycteropus afer afer | Aardvark | CVGFSLKKEKRKKIQKVLFANRRLKIRK | 11 |

| XP_007076762.1 | Panthera tigris altaica | Amur Tiger | CVKALKKEKNKKMPKLFFANKRLKIWKR | 11 |

| XP_004431409.1 | Ceratotherium simum simum | Southern White Rhinoceros | CTKALKKKKNRKMPKLFLANRSLKLRRK | 13 |

| XP_004386213.1 | Trichechus manatus latirostris | Florida manatee | CAKALKKKKKKIRKFVLASRSLKLQKKQ | 13 |

| XP_006733001.1 | Leptonychotes weddellii | Weddell seal | CIKAVRKQKDKKTPKIVFAHRRVKTWKK | 11 |

| XP_007450700.1 | Lipotes vexillifer | Yangtze River dolphin | CVKALKKGKNKKMPKLLFASRRLKIKKK | 13 |

| XP_004265641.1 | Orcinus orca | Killer Whale | CVKALKKGKNKKMPKLLFASRRLKIKKK | 13 |

| BIRDS | ||||

| XP_010710984 | Meleagris gallopavo | Wild Turkey | CKKGSQKPTISKPRNLLRRKMMRKLIKK | 12 |

| XP_009328855.1 | Pygoscelis adeliae | Adélie penguin | CRKGTQKPRINKPMNVFRRKVMRKLIKK | 12 |

| XP_010560815 | Haliaeetus leucocephalus | Bald eagle | CRKAGTQKPRINKPTNVFRRKMMRKLIK | 11 |

| XP_005228880.1 | Falco peregrinus | Peregrine falcon | CRKGTQKPRINKPANVFRRKMMRKLTKK | 12 |

| XP_009934468.1 | Opisthocomus hoazin | Hoatzin | CRKGTEKPRINKPTNVFRRKMMRKLVKK | 11 |

| XP_009893654.1 | Charadrius vociferus | Killdeer | CRKAGAQKPRIDKPTNVFRRKMMRKLIK | 10 |

| XP_009639692.1 | Egretta garzetta | Little egret | CRKGTEKPGINKPMNVFRRKMMRKLTKK | 10 |

| XP_009672625.1 | Struthio camelus australis | Ostrich | CRKGSEKPRINKPANLLRRKMMRKLIKK | 11 |

| XP_009464906.1 | Nipponia nippon | Crested Ibis | CRKGTEKPRINKPTNVFRRKMMRKLIKK | 11 |

| XP_009084577.1 | Serinus canaria | Atlantic canary | CRKAGNQKPSINKPTNLSRRKIVRKLKK | 11 |

| XP_008919443.1 | Manacus vitellinus | Golden-collared manakin | CRKGTQKPRINKPMSVSRRKIMRKLIKK | 12 |

| XP_008492487.1 | Calypte anna | Anna’s hummingbird | CRKAGTQKPKINKPVNGVRRKMMIKLIK | 11 |

| XP_005518860.1 | Pseudopodoces humilis | Ground tit | CGKGNQKLRINKPTNVSRRKIVRKLIEK | 9 |

| XP_005152979.1 | Melopsittacus undulatus | Budgerigar | CRKGTQKPGINKPMNVFRRKMMRKLVKK | 11 |

| XP_005041216.1 | Ficedula albicollis | The collared flycatcher | CRNAGNQKLRINKPTNVSRRKLVRKLIK | 10 |

| XP_005010988.1 | Anas platyrhynchos | Mallard | CGKAGSQKPAMKKSTDVFRRKMMRKLIK | 9 |

| XP_418662.2 | Gallus gallus | Chicken | CRKGSQKPTINKSRSLLRRKMMRKLIKK | 12 |

| XP_005418689.1 | Geospiza fortis | Medium ground finch | CRNGNQKPGINKPTNLSRRKIVRKLKKK | 11 |

| XP_005480303.1 | Zonotrichia albicollis | White-throated Sparrow | CRNAGNQKPAINKPANLSRRKIVRKLKK | 10 |

| REPTILES | ||||

| XP_005308608.1 | Chrysemys picta bellii | Western painted turtle | CKKAGSKKSSFKKSRNKLPKTMRKLPEK | 11 |

| XP_006258519.1 | Alligator Mississippiensis | American Alligator | CRKAGNKKPRIKPKSKVMRKMMRKLQKN | 13 |

| AMPHIBIANS | ||||

| Q5FVY6 | Xenopus tropicalis | Western clawed frog | CKKGSKRPRNRNRIRVPRIQS | 9 |

| FISHES | ||||

| XP_010889816.1 | Esox lucius | The northern pike | CAKAGKLWKTKNPVTKTAMMKIPKKRSR | 10 |

| XP_010739844.1 | Larimichthys crocea | Croceine croaker | CAKGGKKYKRQGKGRRMRRYRNNNITFL | 11 |

| XP_008419957.1 | Poecilia reticulata | Guppy | CVRGPKRHSSHGKLRRLRQNRNNHLPLH | 8 |

| XP_008329541.1 | Cynoglossus semilaevis | Cynoglossus | CVKGEKKHTGQGMIRRLRRNKNNSIFVV | 7 |

| XP_008287494.1 | Stegastes partitus | Bicolor damselfish | CVKGAKKQTGQGKGRRMRRNRHNHITFL | 9 |

| XP_007259866.1 | Mexican tetra | Astyanax mexicanus | CARKSKPGKMRRKLIPRKPERRI | 10 |

| C3KHI5 | Anoplopoma fimbria | Sablefish | CVTGRKHTIQSKGRRLRRNRINRITFRQ | 10 |

| Q1WCN6 | Danio rerio | Zebrafish | CGSKRWSPTKKSVRVSKQYLRRVKPQPS | 9 |

| I3JXJ8 | Oreochromis niloticus | Nile tilapia | CAKGWKKHPGRGKILRSRKNRKLVTFLQ | 10 |

| XP_003969359.1 | Takifugu rubripes | Japanese Puffer | CVRGRKIRTREGKTNPLRRNRNNRITFM | 9 |

| XP_004073873.1 | Oryzias latipes | Japanese Rice Fish | CLKGAKKHTGLKGRDRLMKRNKKTRFMA | 10 |

| XP_010772945.1 | Notothenia coriiceps | Black Rock Cod | CARRGKKLTSQVKGRRKRRNRNNRITFL | 12 |

| XP_007903512.1 | Callorhinchus milii | Australian Ghostshark | CQKRNKKKTSQKYPTASITRKVVKKNSR | 11 |

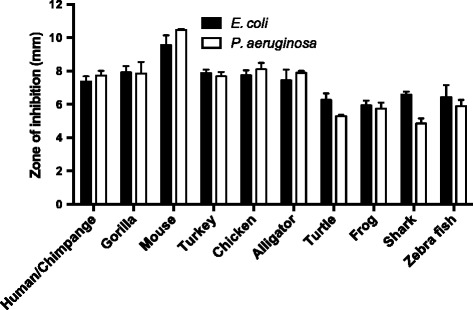

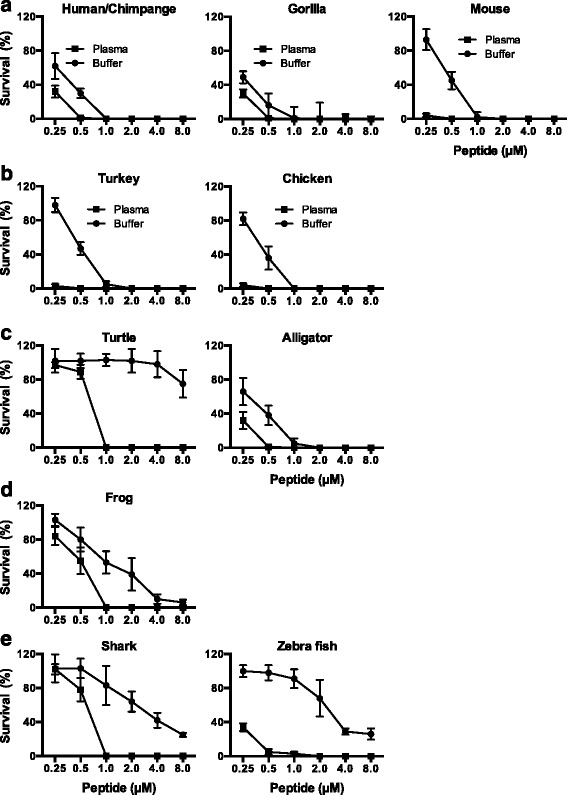

Antimicrobial activities of TFPI-2 C-terminal derived peptides

Having identified the C-terminal region of TFPI-2, we next wished to investigate whether other vertebrate derived peptides retain similar bactericidal activity compared to the human peptide. The antimicrobial properties of the C-terminal TFPI-2 derived peptides from different vertebrates were assessed using radial diffusion assay against gram-negative bacteria E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 3). These species included primates (human and gorilla), rodents (mouse), birds (turkey and chicken), reptiles (alligator and turtle), amphibians (frog) and fishes (shark and zebra fish). We also noted that all vertebrate peptides displayed antimicrobial activities at concentrations of 100 μM against both bacteria. In consensus with the human peptide, we investigated if also other vertebrate-derived peptides display enhanced bactericidal activity in presence of plasma. To this end, the peptides were incubated at varying concentrations with E. coli in presence of physiological buffer containing 20 % human citrate plasma, since this E. coli strain is complement sensitive. In concordance with previous data, all vertebrate peptides displayed enhanced bactericidal activity against E. coli. Complete bacterial killing was observed at a concentration of 1 μM in human plasma, which is due to boosting complement activation, whereas higher concentrations of the peptides were required for their direct antimicrobial activity as seen from incubating the peptide in presence of buffer (Fig. 4). The growth of bacteria in buffer is slower than in citrated plasma, but the peptide-mediated killing in buffer is still less efficient than in citrated plasma.

Fig. 3.

Antimicrobial activities of TFPI-2 C-terminal derived peptides from different species. For determination of antimicrobial activities, E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (4 × 106 cfu) were inoculated in 0.1 % TSB agarose gel. Each 4 mm-diameter well was loaded with 6 μl of peptide (at 100 μM). The zones of clearance (in mm) correspond to the inhibitory effect of each peptide after incubation at 37 °C for 18–24 h (mean values are presented, n = 3). A control with buffer only yielded no inhibition zone

Fig. 4.

Activities of TFPI-2 C-terminal derived peptides in human plasma. The bactericidal activity of TFPI-2 peptides was assessed in physiological buffer conditions using viable count analysis. a–e Bacteria E. coli ATCC 25922 were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and incubated with varying concentrations of peptides corresponding to sequences found in mammals, birds, reptiles, frog and fish species. Peptides were used in buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4 alone, or in presence of 20 % human plasma. The antimicrobial activity was determined by plating serial dilution of bacteria on TH agar plates and number of cfu was counted after overnight incubation. All investigated peptides showed dose dependent bactericidal activity and 100 % bacterial killing was achieved in all cases at 1 μM concentration

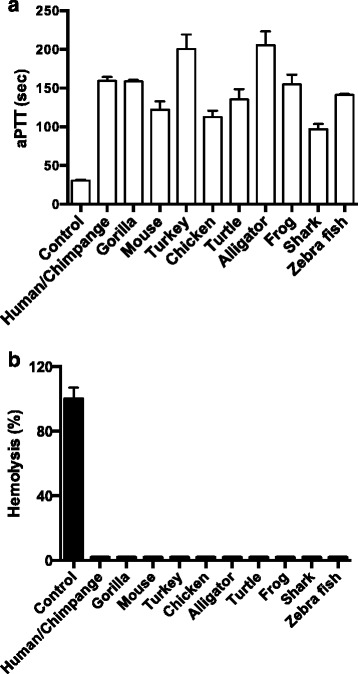

Effect of TFPI-2 derived peptides on blood coagulation/intrinsic pathway of coagulation

Previously, it was shown that the human TFPI-2 derived peptide EDC34 blocks the intrinsic pathway of coagulation in both human and murine plasma [22]. Based on these findings we investigated the anticoagulant activity of the vertebrate-derived TFPI-2 peptides by determining the prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). As shown in Fig. 5a, all peptides effectively prolonged the normal clotting time on aPTT by more than 100 s when applied at a concentration of 50 μM. We further noted that all vertebrate-derived anticoagulant peptides tested are non-hemolytic at 60 μM and thus have potential to be used in therapeutic applications (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Anticoagulant effects of TFPI-2 derived peptides. a The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was determined by addition of buffer or 50 μM of different vertebrate TFPI-2 derived peptides to human plasma. Data are presented as clotting time in seconds; values are mean ± SD (n = 3). b Human erythrocytes were incubated with 60 μM of vertebrate TFPI-2 derived peptides. The hemoglobin release was measured at λ 540 nm and hemolysis was indicated in percentage, Triton X-100 treated sample being used a positive control

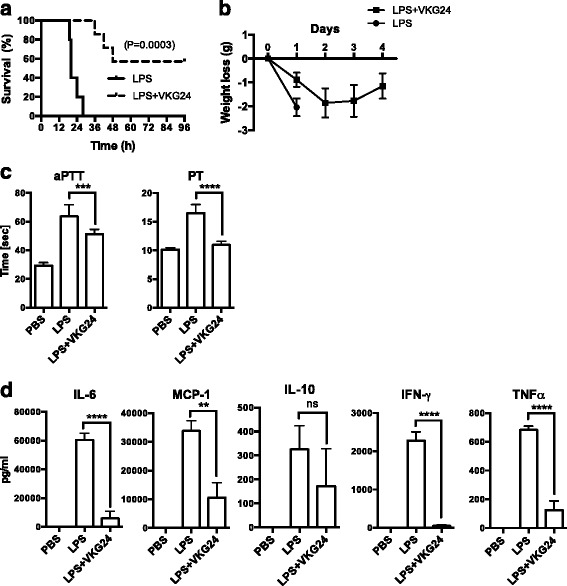

Mouse C-terminal TFPI-2 derived VKG24 peptide provides protection against septic shock

Given the observed effects of the TFPI-2 C-terminal peptides, we made an attempt to find out whether these peptides are of therapeutic importance. To test whether the endogenous C-terminal TFPI-2 region is important in host defense, the mouse peptide VKG24 was chosen for a murine in vivo model. In vitro, VKG24 peptide displayed potent antimicrobial and anti-coagulant activities in mouse plasma (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Thus, the in vivo efficiency of VKG24 peptide was evaluated in a standardized mouse model of endotoxin-induced shock [22]. A dramatic improvement in the survival rate of the animals was seen after treatment with the peptide (~25 mg/kg body weight) (Fig. 6a). Peptide-treated animals started regaining their weight from day three (Fig. 6b). Previous studies have shown that thrombocytopenia is as an important indicator for the severity of sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation [23]. Therefore, activation of the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways was measured in citrate plasma of LPS-injected mice that received a VKG24 injection or were left untreated. The treatment showed significantly decreased coagulation aPTT and PT times in LPS challenged mice, indicating that the peptide reduced consumption of coagulation proteins (Fig. 6c). The levels were completely normalized in the survivors after seven days. Analyses of the cytokine profile 24 h after LPS injection showed significant reduction of IL-6, MCP-1, IFN-γ and IL-10, respectively (Fig. 6d). Thus, the results demonstrate that the mouse VKG24 peptide exerts potent immunomodulatory activity.

Fig. 6.

Treatment of LPS-induced septic shock mice with a mouse TFPI-2 derived peptide. Septic shock in Balb/c mice was induced by i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg E. coli LPS. Thirty minutes after LPS injection, VKG24 (0.5 mg/mouse or ~25 mg/kg body weight) or PBS was administrated i.p. a Mouse TFPI-2 derived peptide significantly increased survival of mice. Survival of mice was monitored for 7 days (only the first 96 h is shown in the figure). Statistical comparisons of survival curves were performed using the Mantel-Cox’s test. ***P ≤ 0.0003. b Weight was determined daily. c Clotting times of aPTT and PT was measured in citrate plasma 24 h after LPS injection (n = 8). d The indicated cytokines were analyzed in plasma 24 h after LPS injection (n = 8). Statistical analysis for C-D, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test was used. **P ≤ 0.003, ****P ≤ 0.0001

Discussion

In the present study we aimed to study the host defence and immunomodulatory activities of the vertebrate C-terminal epitope of TFPI-2. Sequence analysis of this region in different vertebrate species showed that the exact amino acid sequence was not well conserved, whereas the net positive charge appeared to be preserved. These findings suggest an essential function of the charge. It can be speculated that there has been an evolutionary pressure to maintain the positive charge in the C-terminal region, as this is important in the host defence against bacterial pathogens. Within the last years, TFPI-2 has attracted increasing attention because of its ubiquitous presence, which leads to the deposition in a variety of tissues and particularly in the extracellular matrix. This likely reflects its potential as a central regulator of multiple biological processes involving the control of inflammatory reactions, matrix protease activity, coagulation, angiogenesis, and tumour growth. In previous studies we found that the proteolysis of human TFPI-2 generates C-terminal fragments, both in vivo and in vitro after digestion with neutrophil elastase. These findings are of importance in the context of proteolysis of TFPI-2 and possible release of bioactive host defence fragments [9, 10]. Notably, the observed generation of C-terminal fragments of TFPI-2 are very similar to that seen with TFPI-1, suggesting that the same cleavage sites is used by plasmin and thrombin to generate the C-terminal part of TFPI-1. Interestingly, previous data on TFPI-1 and TFPI-2 revealed that the release of C-terminal peptides may exert similar complement boosting effects [8–10]. It is also notable that the C-terminal peptide of TFPI-1, GGL27, and TFPI-2, EDC34 prolongs aPTT, thus further illustrating a functional overlap between the two TFPI proteins. In a broader perspective, a picture thus emerges; suggesting that C-terminal fragments from both TFPI-1 and TFPI-2 may be released during inflammation and infection, serving as modulators of both antimicrobial activity and coagulation. So far, available structural and functional data separate the C-terminal TFPI-2 peptides from the group of classical amphipathic antimicrobial peptides, such as the helical cathelicidin peptide LL-37 as well as defensins. Indeed, the EDC34 show a similarity to some linear peptides of low helical content, such as antimicrobial peptides derived from growth factors [24] as well as human kininogen, all displaying mostly random coil conformation in buffer and at lipid bilayers, the interactions dominated by electrostatic interactions [25].

It remains to be investigated whether TFPI-2 peptides may have similar actions as those reported here, although the absence of a marked boosting of activity in plasma suggests that complement interactions are characteristic for the TFPI-peptides. The detailed mode of action of these peptides remains to be explored, but it seems that they are involved in interactions with C1q and/or other molecules that can initiate the classical pathway of complement and lead to the formation of C3a or a MAC complex. Contact activation, involving degradation of human kininogen, and release of vasoactive bradykinin has been reported during various infective processes including sepsis [26, 27]. The finding that EDC34 inhibited contact activation in vitro is of importance, since a generalized activation of the system can be deleterious.

From a clinical perspective, many opportunistic bacteria can cause both localized and systemic infections and are responsible for considerable mortality or morbidity in patients suffering from burn wound infections, pneumonia, cystic fibrosis, intra-abdominal infections, chronic ulcers, and sepsis. Our results show a direct antimicrobial activity of the TFPI-2 peptide derived from different vertebrates species. The potent antimicrobial activity of these peptides was paired with boosting of complement activation and a modulation of the coagulation cascade. In vivo, VKG24 administration after LPS challenge protects mice and also significantly reduced aPTT and PT time. Therefore, our findings that VKG24 is able to significantly reduce LPS induced shock is particularly relevant, and implies a therapeutic potential for VKG24. The protective effect of mouse VKG24 in infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens may also apply to other vertebrate TFPI-2 C-terminal peptides.

Conclusions

Several therapeutic strategies to combat severe infections including sepsis are based on supplementation of antibiotics with molecules exerting anti-coagulant and anti-inflammatory actions [28]. The dual effects of these natural peptides, for example the mouse derived VKG24 peptide, that can block contact activation and boost complement activation, thus represent, to our knowledge, a novel treatment concept, which could enable complement mediated bacterial clearance while inhibiting the deleterious effects of excessive procoagulant responses during infection with Gram-negative bacteria.

Methods

Peptides

Indicated peptides (Additional file 3: Table S1) were synthesized by Ontores (Shanghai, China). The purity (>98 %) of these peptides was confirmed by mass spectral analysis (MALDI-ToF Voyager).

Microorganisms

The bacterial isolates E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection.

Radial diffusion assay (RDA)

Essentially as described earlier, bacteria were grown to mid-logarithmic phase in 10 ml of full-strength (3 % w/v) trypticase soy broth (TSB) (Becton-Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD). The microorganisms were then washed once with 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4. Subsequently, 4 × 106 bacterial colony forming units (cfu) were added to 15 ml of the underlay agarose gel, consisting of 0.03 % (w/v) TSB, 1 % (w/v) low electroendosmosis type (EEO) agarose (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and 0.02 % (v/v) Tween 20 (Sigma). The underlay was poured into a Ø 144 mm petri dish. After agarose solidification, 4 mm-diameter wells were punched and 6 μl of test sample was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h to allow diffusion of the peptides. The underlay gel was then covered with 15 ml of molten overlay (6 % TSB and 1 % Low-EEO agarose in distilled H2O). Antimicrobial activity of a peptide is visualized as a zone of clearing around each well after 18–24 h of incubation at 37 °C.

Viable count analysis (VCA)

E. coli were grown to mid-exponential phase in Todd-Hewitt (TH). Bacteria were washed and diluted in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4 either alone or with 20 % human or mouse (BALB/c) citrate-plasma. Bacterial (2 × 106 cfu/ml) were incubated in 50 μl, at 37 °C for 1 h with the C-terminal TFPI-2 derived peptides at the indicated concentrations. Serial dilutions of the incubation mixture were plated on TH agar, followed by incubation at 37 °C overnight and cfu determination.

LPS animal model

Male/female balb/c mice (8 weeks, 21 ± 5 g) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 10 mg E. coli 0111:B4 LPS (Sigma) per kg of body weight. Thirty minutes after LPS injection, 0.5 mg VKG24 (25 mg/kg) or PBS buffer alone (control) were injected i.p. into the mice. Status and weight were monitored daily for seven days. Mice where immobilization and/or shaking was observed were euthanized by an overdose of isoflurane (Abbott) and counted as non-survivors. For determination of cytokine levels in mouse plasma, animals were sacrificed 24 h after LPS injection. The blood was collected immediately by cardiac puncture into citrate tubes.

Cytokine assay

Cytokines IL-6, IL-10, MCP-1, INF-γ and TNF-α were measured in plasma from mice infected by E. coli LPS (with or without peptide treatment) using the Cytometric bead array; mouse inflammation kit (Becton Dickinson AB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All plasma samples were stored at −80 °C before the analysis.

Hemolysis assay

EDTA-blood was centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min, where after plasma and buffy coat were removed. The erythrocytes were washed three times and resuspended in PBS, pH 7.4 to get a 5 % suspension. The cells were then incubated with end-over-end rotation for 60 min at 37 °C in the presence of peptides (60 μM). Triton X-100 (Sigma) 2 % served as positive control. The samples were then centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 min and the supernatant was transferred to a 96 well microtiter plate. The absorbance of hemoglobin release was measured at 540 nm and expressed as percentage of Triton X-100 induced hemolysis.

Phylogenetic and sequence homology analyses

Various vertebrate TFPI-2 amino acid sequences, which are presently available, were retrieved from the NCBI, Ensembl and Uniprot. These sequences were aligned using Blosum 69 protein weight matrix settings using BioEdit software (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA). Internal adjustments were made taking the structural alignment into account utilizing the ClustalW interface. Neighbor-joining method was used for phylogenetic tree construction, and the reliability of each branch was assessed using 1000 bootstrap replications using Mega-6.

Clotting assays

All clotting times were analyzed using a coagulometer (Amelung, Lemgo, Germany). For determination of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), 100 μl of a kaolin-containing solution (Technoclone) was added to the 100 μl of fresh citrate plasma or citrate plasma peptide mix and incubated at 37 °C for 200 s before clot formation was initiated by adding 100 μl of 30 mM fresh CaCl2 solution. For detection of prothrombin time (PT, thromboplastin reagent (Trinity Biotech)) 100 μl of fresh citrate plasma were incubated 60 s at 37 °C before clot formation was initiated by adding 100 μl of clotting reagent.

Statistical analysis

Values are shown as mean with SEM. For statistical evaluation of two experimental groups, one-way with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test was used and for comparison of survival curves the Mantel-Cox’s test. Viable count and radial diffusion assay data are presented as mean with SD. All statistical evaluations were performed using the GraphPad Prism software 6.0 with *p- < 0.05, **p- < 0.01, *** < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 and ns = not significant.

Abbreviations

TFPI-2, tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; PT, prothrombin time

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Professors Heiko Herwald, Artur Schmidtchen and Arne Egesten for their support.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Crafoord (http://www.crafoord.se) and The Royal Physiographic Society in Lund (http://www.fysiografen.se/sv/).

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article. For phylogenetic analysis, vertebrate species protein accession numbers are available in Table 1.

Authors’ contributions

PP designed the experiments. GK, ES, EM, LW, SA and PP performed the experiments. PP analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animals were housed under standard conditions of light and temperature and had free access to standard laboratory chow and water. Animal use protocols (M185-14) were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Malmö/Lund.

Additional files

Phylogenetic tree analysis of full-length and reminder protein except C-terminal TFPI-2 from vertebrates. Phylogenetic tree from 72 vertebrate TFPI-2 species was constructed using Neighbour-Joining tree with 1000 bootstrap replications on MEGA6. (PDF 54 kb)

Activities of TFPI-2 C-terminal derived peptides in mouse plasma. (Left) The bactericidal activity of mouse VKG24 peptide was assessed in physiological buffer conditions using viable count analysis. E. coli ATCC 25922 were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and incubated with varying concentrations of peptide. The antimicrobial activity was determined by plating serial dilutions of bacteria on TH agar plates and number of cfu was counted after overnight incubation. (Right) The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was determined by addition of buffer or 50 μM of VKG24 peptide to mouse plasma. Data are presented as clotting time in seconds; values are mean ± SD (n = 3). (PDF 32 kb)

Selected vertebrate TFPI-2 C-terminal peptides showing sequence entry name, species, sequence, charge and hydrophobicity. (PDF 73 kb)

Contributor Information

Gopinath Kasetty, Email: gopinath.kasetty@med.lu.se.

Emanuel Smeds, Email: Emanuel.smeds@med.lu.se.

Emelie Holmberg, Email: Emelie.holmberg.134@student.lu.se.

Louise Wrange, Email: Louise.wrange.121@student.lu.se.

Selvi Adikesavan, Email: Selvi.a2013@vit.ac.in.

Praveen Papareddy, Phone: 46-46-222 68 06, FAX: 46-46-15 77 56, Email: praveen.papareddy@med.lu.se.

References

- 1.Krem MM, Di Cera E. Evolution of enzyme cascades from embryonic development to blood coagulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27(2):67–74. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(01)02007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papareddy P, Rydengård V, Pasupuleti M, Walse B, Mörgelin M, Chalupka A, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A Proteolysis of human thrombin generates novel host defense peptides. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4), e1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Frick IM, Åkesson P, Herwald H, Mörgelin M, Malmsten M, Nagler DK, Björck L. The contact system--a novel branch of innate immunity generating antibacterial peptides. Embo J. 2006;25(23):5569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Malmström E, Mörgelin M, Malmsten M, Johansson L, Norrby-Teglund A, Shannon O, Schmidtchen A, Meijers JC, Herwald H. Protein C inhibitor--a novel antimicrobial agent. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(12), e1000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Tang YQ, Yeaman MR, Selsted ME. Antimicrobial peptides from human platelets. Infect Immun. 2002;70(12):6524–33. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6524-6533.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedel T, Suttnar J, Brynda E, Houska M, Medved L, Dyr JE. Fibrinopeptides A and B release in the process of surface fibrin formation. Blood. 2011;117(5):1700–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papareddy P, Kalle M, Bhongir RK, Mörgelin M, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A. Antimicrobial effects of helix D-derived peptides of human antithrombin III. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(43):29790–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Papareddy P, Kalle M, Kasetty G, Mörgelin M, Rydengård V, Albiger B, Lundqvist K, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A. C-terminal peptides of tissue factor pathway inhibitor are novel host defense molecules. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):28387–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Papareddy P, Kalle M, Sorensen OE, Lundqvist K, Mörgelin M, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 is found in skin and its C-terminal region encodes for antibacterial activity. PLoS One. 2012;7(12), e52772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Papareddy P, Kalle M, Sorensen OE, Malmsten M, Mörgelin M, Schmidtchen A. The TFPI-2 derived peptide EDC34 improves outcome of gram-negative sepsis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(12), e1003803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hilchie AL, Wuerth K, Hancock RE. Immune modulation by multifaceted cationic host defense (antimicrobial) peptides. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9(12):761–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KY, Chow LN, Mookherjee N. Cationic host defence peptides: multifaceted role in immune modulation and inflammation. J Innate Immun. 2012;4(4):361–70. doi: 10.1159/000336630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock RE, Nijnik A, Philpott DJ. Modulating immunity as a therapy for bacterial infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(4):243–54. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chand HS, Foster DC, Kisiel W. Structure, function and biology of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(6):1122–30. doi: 10.1160/TH05-07-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprecher CA, Kisiel W, Mathewes S, Foster DC. Molecular cloning, expression, and partial characterization of a second human tissue-factor-pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(8):3353–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udagawa K, Miyagi Y, Hirahara F, Miyagi E, Nagashima Y, Minaguchi H, Misugi K, Yasumitsu H, Miyazaki K. Specific expression of PP5/TFPI2 mRNA by syncytiotrophoblasts in human placenta as revealed by in situ hybridization. Placenta. 1998;19(2–3):217–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Iino M, Foster DC, Kisiel W. Quantification and characterization of human endothelial cell-derived tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(1):40–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.18.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petersen LC, Sprecher CA, Foster DC, Blumberg H, Hamamoto T, Kisiel W. Inhibitory properties of a novel human Kunitz-type protease inhibitor homologous to tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1996;35(1):266–72. doi: 10.1021/bi951501d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong D, Ma D, Bai H, Guo H, Cai X, Mo W, Tang Q, Song H. Expression and characterization of the first kunitz domain of human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(4):1179–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hisaka T, Lardeux B, Lamireau T, Wuestefeld T, Lalor PF, Neaud V, Maurel P, Desmouliere A, Kisiel W, Trautwein C et al. Expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in murine and human liver regulation during inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91(3):569–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Torres-Collado AX, Kisiel W, Iruela-Arispe ML, Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC. ADAMTS1 interacts with, cleaves, and modifies the extracellular location of the matrix inhibitor tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):17827–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalle M, Papareddy P, Kasetty G, Mörgelin M, van der Plas MJ, Rydengård V, Malmsten M, Albiger B, Schmidtchen A. Host defense peptides of thrombin modulate inflammation and coagulation in endotoxin-mediated shock and Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. PLoS One. 2012;7(12), e51313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Levi M, Schultz M, van der Poll T. Sepsis and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(5):559–66. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malmsten M, Davoudi M, Walse B, Rydengård V, Pasupuleti M, Mörgelin M, Schmidtchen A. Antimicrobial peptides derived from growth factors. Growth Factors. 2007;25(1):60–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ringstad L, Andersson Nordahl E, Schmidtchen A, Malmsten M. Composition effect on peptide interaction with lipids and bacteria: variants of C3a peptide CNY21. Biophys J. 2007;92(1):87–98. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.088161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persson K, Mörgelin M, Lindbom L, Alm P, Björck L, Herwald H. Severe lung lesions caused by Salmonella are prevented by inhibition of the contact system. J Exp Med. 2000;192(10):1415–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Pixley RA, DeLa Cadena RA, Page JD, Kaufman N, Wyshock EG, Colman RW, Chang A, Taylor FB, Jr.. Activation of the contact system in lethal hypotensive bacteremia in a baboon model. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(4):897–906. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.de Jong HK, van der Poll T, Wiersinga WJ. The systemic pro-inflammatory response in sepsis. J Innate Immun. 2010;2(5):422–30. doi: 10.1159/000316286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article. For phylogenetic analysis, vertebrate species protein accession numbers are available in Table 1.