Abstract

Background:

The current standard recommendation is to avoid surgical interventions in patients taking oral isotretinoin. However, this recommendation has been questioned in several recent publications.

Aim:

To document the safety of cosmetic and surgical interventions, among patients receiving or recently received oral isotretinoin.

Materials and Methods:

Association of Cutaneous Surgeons, India, in May 2012, initiated this study, at 11 centers in different parts of India. The data of 183 cases were collected monthly, from June 2012 to May 2013. Of these 61 patients had stopped oral isotretinoin before surgery and 122 were concomitantly taking oral isotretinoin during the study period. In these 183 patients, a total of 504 interventions were performed. These included[1] 246 sessions of chemical peels such as glycolic acid, salicylic acid, trichloroacetic acid, and combination peels;[2] 158 sessions of lasers such as ablative fractional laser resurfacing with erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet and CO2, conventional full face CO2 laser resurfacing, laser-assisted hair reduction with long-pulsed neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, diode laser, and LASIK surgery;[3] 27 sessions of cold steel surgeries such as microneedling, skin biopsy, subcision, punch elevation of scars, excision of skin lesion, and wisdom tooth extraction;[4] 1 session of electrosurgery.

Results:

No significant side effects were noted in most patients. 2 cases of keloid were documented which amounted to 0.4% of side effects in 504 interventions, with a significant P value of 0.000. Reversible transient side effects were erythema in 10 interventions and hyperpigmentation in 15.

Conclusion:

The study showed that performing dermatosurgical and laser procedures in patients receiving or recently received isotretinoin is safe, and the current guidelines of avoiding dermatosurgical and laser interventions in such patients taking isotretinoin need to be revised.

KEYWORDS: Guidelines, hypertrophic scar, isotretinoin, keloid, side effects

INTRODUCTION

Oral isotretinoin has been in use since 1982, for “severe, nodulocystic acne, refractory to treatment, including oral antibiotics” and since 2000 with expanded indication to include acne which causes physical scarring and psychological impact.[1] With this expanded recommendation, nearly 1.2 million prescriptions were captured from December 2005 to February 2011, through PLEDGE Registry in the US.[2]

Even though the benefits outweigh the risks, isotretinoin has its share of side effects. Of all the side effects, three are significant and subject to much debate-depression and suicidal ideation,[3,4] inflammatory bowel disease,[5] and finally hypertrophic scar and keloid formation.[6]

Of the above, the hypertrophic scar and keloid formation are the focus of this paper. The present established standard preoperative surgical care, so far advises the stoppage of oral isotretinoin 6–12 months before any dermatosurgery.[7] This was based on the early reports of keloids or delayed wound healing, in patients on isotretinoin during surgery documented in 1980's.[8,9] Surprisingly, this recommendation stemmed from 9 cases reported from different authors.

However in 1985, Roenigk et al. had performed dermabrasion in nine patients on isotretinoin and reported normal “initial” skin healing.[10] However, despite this observation, for nearly two decades, stopping oral isotretinoin before dermatosurgery was the medico-legal standard practice, unchallenged.

Between 2004 and 2012, a few case series and prospective studies were published documenting the safety of dermatosurgery and laser therapy in patients on oral isotretinoin. These included laser hair removal with diode laser,[11,12] long-pulsed neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd: YAG) laser,[13] diamond fraise dermabrasion,[14] and chemabrasion.[15] The data are summarized the Table 1. However the studies were small and not significant enough to alter the recommended guideline, and larger studies were needed. The recommendation however put restrictions on physicians while performing procedures in these patients as it would have medicolegal implications and also often denied the right treatment to them.

Table 1.

Oral isotretinoin intake and scarring postintervention – review of literature

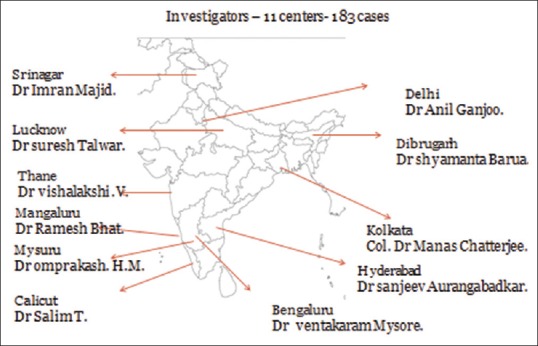

In view of this, to establish proper evidence for a change in the guidelines and facilitate evidence-based practice, in 2012, the Association of Cutaneous Surgeons India, ACS (I) proposed to start a multicentric study to establish the safety of procedures in such patients. The study was named as per acronym ISO-AIMS study which stood for “Isotretinoin and Surgical Outcome: ACS (I) Multicentric Study.” 11 investigators from across India took part in the multicentric trial [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Centers participating in the multicentric trial

MATERIALS AND METHODS

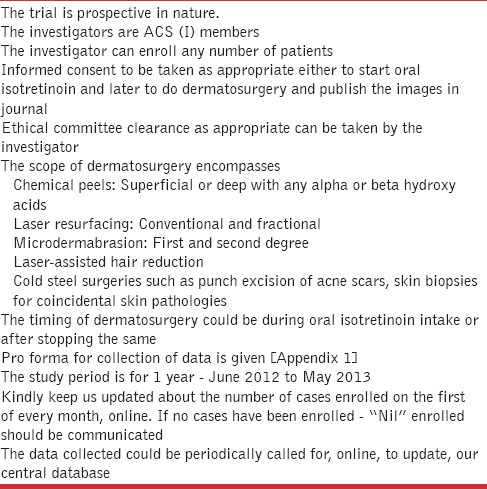

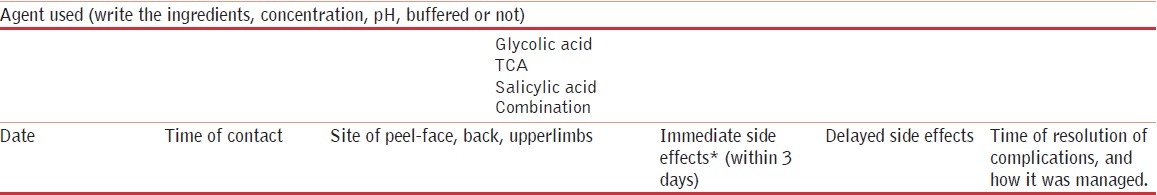

The study was prospective, interventional, and nonblinded in nature. The scope of the study is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scope of study

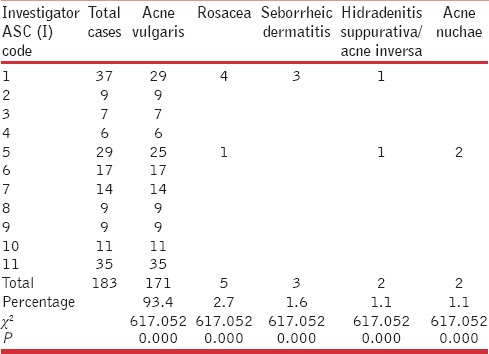

A total of 183 cases were enrolled across 11 centers. The age, sex, and Fitzpatrick skin types are shown in Table 3. The indications for oral isotretinoin are shown in Table 4. Of these patients, 61 had stopped oral isotretinoin intake before surgical intervention and 122 were taking concomitantly isotretinoin during surgical intervention. Dosage range was 2–110 mg/kg (180–9160 mg) [Table 5].

Table 3.

Patient profile

Table 4.

Oral isotretinoin indications data

Table 5.

Isotretinoin – cumulative dosage and usage profile

In the 183 cases, a total of 504 interventions were performed as shown in [Table 6]. The devices and parameters used are shown in Table 7. The data were statistically analyzed using descriptive statistics, contingency coefficient test, and Chi-square test.

Table 6.

Table of procedures

Table 7.

Devices/interventions and some parameters used

Of the 183 cases, 82 cases (44.8%) were of skin type IV, and 72 cases (39.3%) were of skin type V. Furthermore, significant was 122 (66.66%) cases were on concomitant oral isotretinoin. The skin type, age group, and indication for isotretinoin had a significant P < 0.000 except the gender distribution.

Of the interventions, chemical peel – 246 sessions (48.9%) – was the most common performed, followed by different lasers – 184 sessions (37.6%).

RESULTS

Two sets of adverse events were documented [Table 8]. Keloid formation was noted in 2 cases. The second set of adverse events was were transient like-erythema, pigmentation, acne, and hemorrhage. However, 93.8% cases did not have any adverse events.

Table 8.

Adverse events

Laser-diode/long-pulsed Nd: YAG or IPL-assisted hair reduction and acne therapy totaling 38 sessions had no adverse outcome. Salicylic acid peel performed in 30 sessions was without side effects. Microdermabrasion, 44 sessions was also safe. 8 skin biopsies also were safe. One wisdom tooth extraction healed well, despite patient being on isotretinoin. The wisdom tooth extraction outcome in our study concurs with the currently documented experience in literature of 26 cases, which is safe.[16]

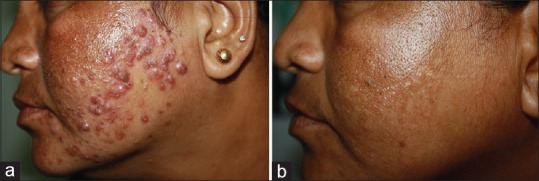

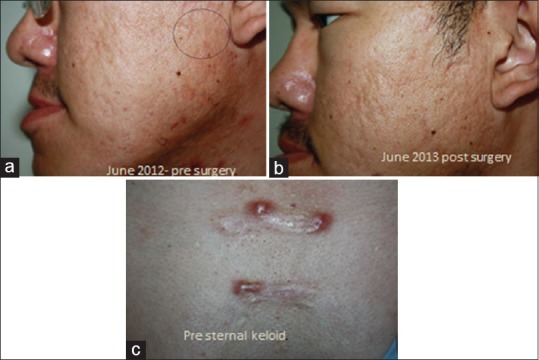

Of the other procedures carried out – in glycolic peel [Figure 2], of 147 cases, 6 had erythema. All had one coat of peel applied. One case on Refinity 70% buffered glycolic peel, had immediate erythema which started with in a minute, which was neutralized and resolved without sequelae (manufacturer recommended contact time 4–10 min). The second case of glycolic acid peel had erythema which resolved only with tacrolimus ointment 0.01% by 2 weeks. The third case had facial keloid formation at the site of glycolic acid application [Figure 3] and interestingly developed keloid later on truncal zone too (cumulative dose in this case - 2100 mg of isotretinoin). This was managed by intralesional steroids. In other procedures, 2 cases of combination peel developed erythema lasting for 5 days.

Figure 2.

Glycolic acid peel in topical steroid induced acne with centrofacial melasma. 70% buffered glycolic acid peel done in a patient with 1800mg of oral isotretinoin intake. (a) Pre peel (b) Post peel

Figure 3.

Keloid formation at site of peel and even distant site.

In the ablative fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er: YAG) series, one had postinflammatory pigmentation, which resolved in 3 weeks. The second case of fractional Er: YAG laser had prolonged redness requiring topical steroids for 2 weeks. The third case in this intervention had a flare of acne treated with adapalene 0.1% gel night daily.

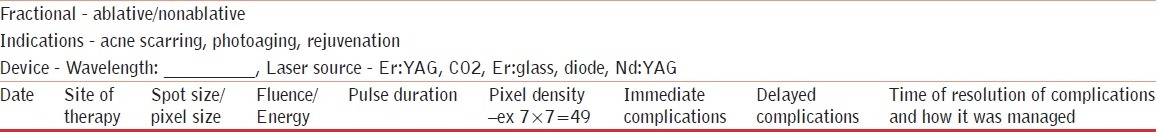

Interestingly, a case with acne vulgaris with a history of keloid on the trunk, who was on isotretinoin, did not develop keloid on the face when fractional Er: YAG laser was used to treat scar on the face [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Pre- and post-fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser resurfacing in a case of preexisting keloid. (a) Pre surgery (b) Post surgery (c) Pre sternal keloid

Conventional ablative CO2 laser resurfacing was done in 19 cases on face. Of these 14 cases developed post inflammatory hyperpigmentation, which resolved with sunscreen and hydroquinone by 3 months. However, none developed keloid or delayed wound healing.

The only microneedling case enrolled and subjected to 7 sessions of therapy had pigmentation which resolved.

A single case of acne vulgaris with nevus of Hori underwent 4 sessions with Q-switched Nd: YAG laser had erythema twice posttherapy which lasted for few minutes and resolved.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage post-LASIK surgery (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis) in a case resolved without permanent sequelae. It is known that isotretinoin causes corneal xerosis, so does LASIK surgery. LASIK surgery is contraindicated during isotretinoin. A gap of 6 months has been advocated before surgery. Furthermore, post-LASIK, isotretinoin should not be prescribed for nearly 6 months.[17]

In this study, not only facial fractional resurfacing but also extrafacial fractional resurfacing was done. One case of Er: Yag fractional laser and one case of CO2 fractional resurfacing were done on trunk region without any side effects.

Radiofrequency ablation of compound nevi on the face was done, in a case, with a cumulative dose of 4000 mg of isotretinoin. This patient developed a keloid.

Two cases of keloid were documented, which amounted to 0.4% of side effects in 504 interventions, with a significant P value of 0.000.

DISCUSSION

Of interest, in this prospective interventional study – “102 Fractional Er: YAG laser resurfacing, 19 conventional full face CO2 laser resurfacing, 19 Fractional CO2 laser resurfacing, 8 skin biopsies;” had no keloid/hypertrophic scar formation or delayed healing. All the above were collagen-specific interventions.

Laser or IPL-assisted hair reduction, being performed in 38 sessions, being more melanin specific, had no keloid/hypertrophic scar formation.

Thirty sessions of salicylic acid peels, 65 sessions of combination peels had no keloid/hypertrophic scar formation. However, of 147 sessions of glycolic acid peel, one case developed keloid at the site of peel and distant site postprocedure. This event of distant site keloid could be idiosyncratic.

The second case of keloid on the face followed radiofrequency ablation of compound nevi.

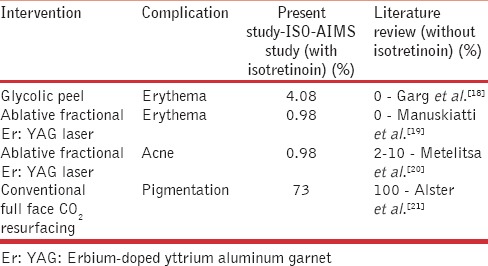

However, there were minor reversible outcomes such as pigmentation, erythema, and acne. If one compares our study and literature, which could serve like control data, the occurrence of reversible events in isotretinoin group is comparable [Table 9].

Table 9.

Comparison of adverse events in ISO-AIMS study and literature review

In a recent retrospective study,[22] about 55 patients undergoing laser-assisted hair reduction and postacne scar reduction in patient taking oral isotretinoin; the authors found no keloid or hypertrophic scar or delayed wound healing.

CONCLUSION

This study with 504 interventions done in patients taking oral isotretinoin with – glycolic/salicylic/combination acid peels, fractional Er: YAG laser resurfacing/fractional CO2 laser and conventional CO2 laser resurfacing, microdermabrasion had a single documented keloid in glycolic peel group. This was probably idiosyncratic. The second case of keloid following radiofrequency ablation of compound nevi however could not be explained.

The results of this study, further enhance the already accumulating evidence, about the safety of procedures in patients receiving isotretinoin and further provide additional evidence that the current recommendations for avoiding procedures may not be valid and need revision.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1

(Abridged version)

Demographic data

Name: _____________________________________ Age: ________ Sex: __________

Patient identification number (hospital registration number): ____________________

Address: __________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Contact phone numbers: ________________________ E-mail id if present: _________________________________

Occupation: _____________________ Patients skin Fitzpatrick type: _________________________

ACS (I) reporting code:_______________________________

Indication for oral isotretinoin (kindly tick the indication)

1. Acne vulgaris

2. Acne rosacea

3. Other indications ________ (kindly write)

Table 1.

Isotretinoin current dosage, duration, and frequency (kindly fill the data in detail)

![]()

Table 2.

Isotretinoin, past dosage, and duration since stopping

![]()

Relevant patient history

History of keloids/hypertrophic scars________ (yes/no)

Procedures indications

Acne scar- atrophic/ hypertrophic

Postacne macules - hyperpigmentation

Hair reduction

Scars - posttraumatic, chicken pox

Excision of scars/biopsy

Procedure performed

Chemical peel

Hair reduction - laser assisted

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Dermatology Position Statement on Isotretinon (Approved by the Board of Directors 9 December, 2000. Amended by the Board of Directors 25 March, 2003, 11 March, 2004, and 13 November, 2010) [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 02]. Available from: http://www.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Isotretinoin.Pdf .

- 2.Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee; Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Advisorycommittees/calendar/ucm275806.htm .

- 3.Hazen PG, Carney JF, Walker AE, Stewart JJ. Depression – A side effect of 13-cis-retinoic acid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:278–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)80154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigby M. Does isotretinoin increase the risk of depression? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1197–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.9.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey KM, James MP. Treatment of severe acne with isotretinoin in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:653–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdelmalek M, Spencer J. Retinoids and wound healing. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1219–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelmalek M, Spencer J. Retinoids and Wound Healing. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1219–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubenstein R, Roenigk HH, Jr, Stegman SJ, Hanke CW. Atypical keloids after dermabrasion of patients taking isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(2 Pt 1):280–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zachariae H. Delayed wound healing and keloid formation following argon laser treatment or dermabrasion during isotretinoin treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:703–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roenigk HH, Jr, Pinski JB, Robinson JK, Hanke CW. Acne, retinoids, and dermabrasion. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:396–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1985.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatri KA. Diode laser hair removal in patients undergoing isotretinoin therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1205–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassano N, Arpaia N, Vena GA. Diode laser hair removal and isotretinoin therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:380–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31097_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatri KA. The safety of long-pulsed Nd: YAG laser hair removal in skin types III-V patients during concomitant isotretinoin therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11:56–60. doi: 10.1080/14764170802612984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagatin E, dos Santos Guadanhim LR, Yarak S, Kamamoto CS, de Almeida FA. Dermabrasion for acne scars during treatment with oral isotretinoin. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:483–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picosse FR, Yarak S, Cabral NC, Bagatin E. Early chemabrasion for acne scars after treatment with oral isotretinoin. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1521–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma J, Thiboutot DM, Zaenglein AL. The effects of isotretinoin on wisdom tooth extraction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:794–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miles S, McGlathery W, Abernathie B. The importance of screening for laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis operation (LASIK) before prescribing isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:180–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg VK, Sinha S, Sarkar R. Glycolic acid peels versus salicylic-mandelic acid peels in active acne vulgaris and post-acne scarring and hyperpigmentation: A comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manuskiatti W, Iamphonrat T, Wanitphakdeedecha R, Eimpunth S. Comparison of fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet and carbon dioxide lasers in resurfacing of atrophic acne scars in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39((1 Pt 1)):111–20. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metelitsa AI, Alster TS. Fractionated laser skin resurfacing treatment complications: A review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alster T, Hirsch R. Single-pass CO2 laser skin resurfacing of light and dark skin: Extended experience with 52 patients. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2003;5:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandrashekar BS, Varsha DV, Vasanth V, Jagadish P, Madura C, Rajashekar ML. Safety of performing invasive acne scar treatment and laser hair removal in patients on oral isotretinoin: A retrospective study of 110 patients. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1281–5. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]