Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer worldwide. Surgical excision is considered to be the primary therapeutic modality wherever possible. For inoperable cases, 5% imiquimod seems to be a good alternative. We present two cases of nodular pigmented BCCs on the face in elderly women successfully treated with 5% imiquimod cream application resulting in complete clinical clearance of lesion as well as on histology and dermatoscopy. There was no recurrence of the lesion on 2 years follow-up for the first and 1.5 years for the second patient.

KEYWORDS: Basal cell carcinoma, dermatoscopy, imiquimod, immunomodulator

INTRODUCTION

Nonmelanoma skin cancers that primarily include basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma far out-number the melanoma skin cancer. Worldwide BCC is the most common skin cancer with higher incidence in countries closer to the equator. Intermittent intense sun exposure rather than cumulative exposure is an important risk factor.[1] Other risk factors include fair skin, tendency to burn rather than tan, and exposure to therapeutic ionizing radiations.[2] Unlike melanomas, BCCs tend to remain localized and have low mortality. Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice; however, due to lack of infrastructure, it is often not feasible. Surgical excision with wide margins is recommended in cases amenable to surgery or where follow-up is questionable. Various therapeutic modalities are available for cases who are either not fit for or who deny surgical intervention, namely, 5% imiquimod cream and photodynamic therapy. We present two cases of nodular pigmented BCC on the face successfully treated with 5% imiquimod with no histological or dermatoscopic evidence of BCC posttreatment.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 78-year-old woman, known diabetic and hypertensive, presented with a slowly growing black annular plaque with beaded margins of 2.5 cm diameter involving the left cheek in proximity to the nose and nasolabial fold of nearly 10 years duration [Figure 1a]. The histopathology with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain showing nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading is depicted in Figure 2. The patient refused surgery and was started on 5% imiquimod cream once a day application for four consecutive days and betamethasone valerate cream (0.01%) twice daily for remaining 3 days in a week. Marked erythema, scaling, and crusting were observed within 2 weeks after eight applications [Figure 1b]. Imiquimod application was withheld for a week until the inflammation subsided with twice daily application of betamethasone cream. After 12 weeks of resumption of topical imiquimod, clinically, the lesion subsided completely with residual marginal pigmentation and central depigmentation [Figure 1c]. The patient was satisfied with the cosmetic outcome. Dermatoscopy failed to reveal any features of BCC [Figure 3]. The posttreatment biopsy revealed prominent lymphoid infiltrates and fibrosis with clearing up of the nests of basaloid cells [Figure 4]. There was no evidence of recurrence at 24 months of follow-up.

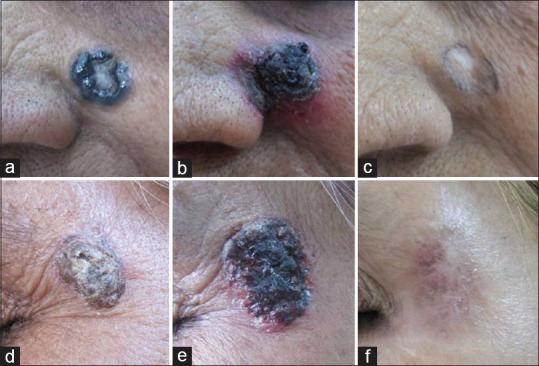

Figure 1.

(a-c) (Case 1) and (d-f) (Case 2) – Basal cell carcinoma lesion pretreatment, at 4 weeks and 12 weeks

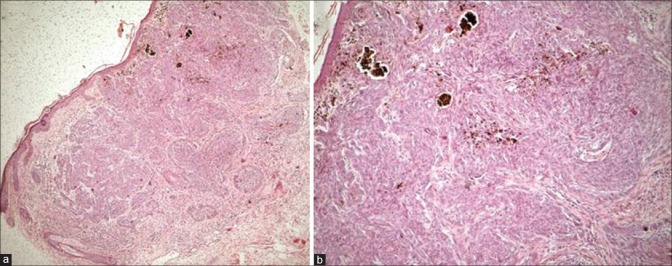

Figure 2.

(a) Pretreatment histology showing epidermal thinning and nests of basaloid tumor cells extending from the epidermis to deep dermis (H and E, ×400). (b) Higher magnification with peripheral palisading of basaloid cells (H and E, ×1000)

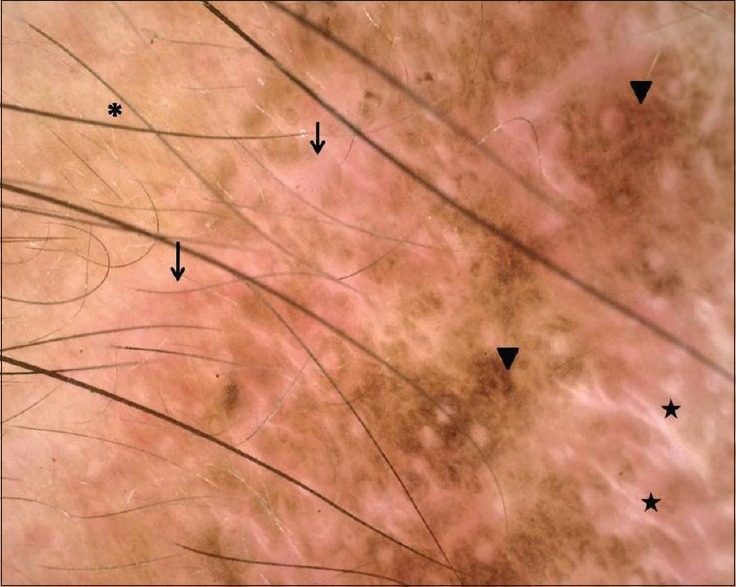

Figure 3.

Dermatoscopy of the residual lesion showing three zones – background erythema with dilated vessels (arrows) most prominent peripherally, followed by a prominent pigment network (arrowheads) and at the center chrysalis-like structures (stars), suggestive of new collagen induction at center. Note perilesional normal skin at upper left corner (Asterix “*”)

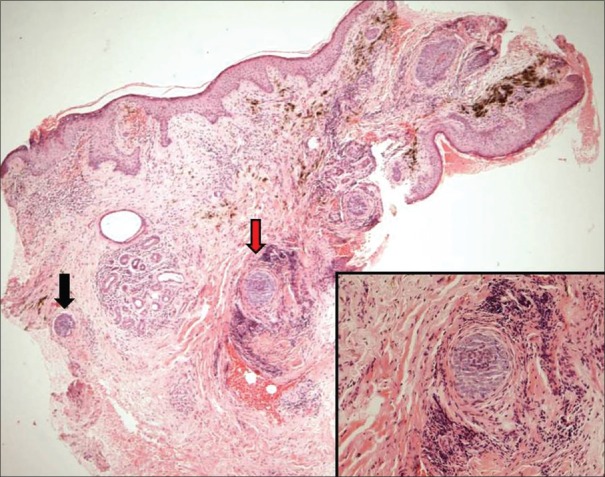

Figure 4.

Posttreatment biopsy-normal epidermis, lymphoid infiltrates in the dermis, and pigment incontinence in superficial dermis. Two tiny foci of basaloid cells in deep dermis (black and red arrows) surrounded by lymphocytic infiltrate and fibrosis representing immune zones (H and E, ×400). Inset: Close up of the foci (red arrow, ×1000)

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman presented with a 3 cm × 2 cm pigmented scaly and crusted plaque in the periorbital area close to the left lateral eyebrow of 6 years duration [Figure 1d]. The histopathology with H&E staining demonstrated nests of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading of nuclei. Due to the proximity with the orbit, the patient was a poor candidate for surgical excision and hence was started on 5% imiquimod cream once a day application for four consecutive days and betamethasone cream on remaining 3 days of the week. Marked erythema and scaling was observed within a week of the therapy [Figure 1e]. The treatment was continued for a total duration of 3 months. Clinically, only mild pigmentation along with a central irregular zone of depigmentation was observed posttreatment [Figure 1f]. Dermatoscopy and posttreatment biopsy showed complete clearance of BCC. Follow-up of 1.5 years revealed no recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Imiquimod is a topically acting immune-modulator with antiviral and antitumor properties, and the US Food and Drug Administration approved it for treatment of genital and perianal warts (1997) and actinic keratoses and superficial BCC <2 cm in 2004.[3]

Imiquimod exerts its effect in BCC via three different mechanisms – induction of proinflammatory cytokines, augmentation of adenosine receptor-associated inflammation, and direct proapoptotic activity, which ultimately induce inflammation that leads to resolution of the lesion.[4] Imiquimod activates both the arms of immune system, innate and cell-mediated through the activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and 8. The activation of TLRs leads to stimulation of a cascade of intracellular pathways that eventually activate the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). This NF-κB leads to induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-α (IFN-α), and IFN-β.

The dosing schedule and treatment duration are not standardized. The recommended schedule in the USA and Europe is 5 times a week for 6 weeks with success rate of 73–77%.[5,6] The most common adverse effects of imiquimod include tumor site reactions (erythema, scaling, ulceration) and flu-like symptoms that may be often severe enough to warrant discontinuation of therapy. Keeping this in mind, two pulsed regimens have also been proposed.[7]

The success rate of surgical treatment is higher than imiquimod. Mohs micrographic surgery has a cure rate of 99%.[8] In a recent multicenter, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial, the cure rate of standard excision was found to be far superior than imiquimod (98% vs. 84%).[9]

Topical imiquimod is primarily indicated in immune-competent individuals with superficial BCC with tumor diameter <2 cm and at sites which are difficult to operate. However, there is a report of treatment of giant facial BCC with topical 5% imiquimod in two patients with complete clinical and histological clearance.[10] This modality of treatment is inappropriate for patients unlikely to follow-up. Although surgical treatment is superior, it is not always feasible, especially in elderly with multiple comorbidities, in difficult sites, and when patient is not willing for surgery. We propose that for such cases imiquimod is a noninvasive, safe, and effective alternative treatment option.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, Nieto A, Miranda A, Mercier M, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: A multi-centre case-case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167–79. eCollection 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jobanputra KS, Rajpal AV, Nagpur NG. Imiquimod. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:466–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.29352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Giorgi V, Salvini C, Chiarugi A, Paglierani M, Maio V, Nicoletti P, et al. In vivo characterization of the inflammatory infiltrate and apoptotic status in imiquimod-treated basal cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:312–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulze HJ, Cribier B, Requena L, Reifenberger J, Ferrándiz C, Garcia Diez A, et al. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: Results from a randomized vehicle-controlled phase III study in Europe. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:939–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisse J, Caro I, Lindholm J, Golitz L, Stampone P, Owens M. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: Results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:722–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezughah FI, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, Fleming CJ. A randomized parallel study to assess the safety and efficacy of two different dosing regimens of 5% imiquimod in the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:111–7. doi: 10.1080/09546630701557965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewin JM, Carucci JA. Advances in the management of basal cell carcinoma. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:53. doi: 10.12703/P7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, Colver GB, Perkins W, Miller PS, et al. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal-cell carcinoma (SINS): A multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:96–105. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun-Guang M, Qi-Man L, Yu-Yun Zh, Li-Hua Ch, Cheng T, Jian-De H. Successful treatment of giant basal cell carcinoma with topical imiquimod 5% cream with long term follow-up. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:575–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.143520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]