Abstract

Nitrogen heterocycles are ubiquitous in natural products and pharmaceuticals. Herein, we disclose a nitrogen complexation strategy that employs a strong Brønsted acid (HBF4) or an azaphilic Lewis acid (BF3) to enable remote, non-directed C(sp3)—H oxidations of tertiary (3°), secondary (2°), and primary (1°) amine- and pyridine- containing molecules with tunable iron catalysts. Imides resist oxidation and promote remote functionalization.

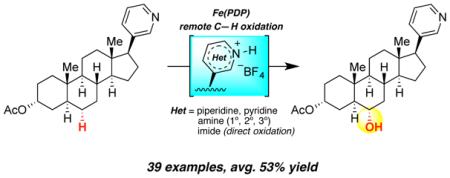

The development of reactions that selectively oxidize inert C(sp3)—H bonds while tolerating more electron rich nitrogen functionality is a significant, unsolved problem given that nitrogen is ubiquitous in natural products and medicinal agents.1 Among the challenges for developing such reactions are catalyst deactivation via nitrogen binding and direct oxidation of nitrogen to furnish N-oxides. Common electronic deactivation strategies for 2° and 1° amines (e.g. acylation) do not disable hyperconjugative activation leading to functionalization α to the nitrogen (Figure 1).2 Directing group strategies facilitate oxidation of C(sp3)—H bonds that are spatially and geometrically accessible from the directing functional group.3 Remote oxidation of C(sp3)—H bonds in nitrogen-containing molecules is not currently possible with ligated transition metal catalysis.

Figure 1.

Heterocycle Functionalization

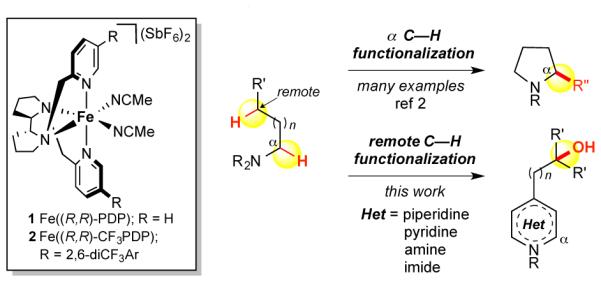

Site-selective and -divergent oxidation of tertiary (3°) and secondary (2°) C—H bonds has been demonstrated with small molecule catalysts, Fe(PDP) 1 and Fe(CF3PDP) 2, respectively.4 Discrimination of C—H bonds can be accom- plished via catalyst/substrate electronic, steric and stereoelectronic interactions. Inductive effects within a substrate strongly influence site-selectivity, as highly electrophilic metal oxidants (e.g. Fe=O) disfavor oxidation of electron-deficient C(sp3)—H bonds. Functionalities with positive charges, such as ammonium cations, or strongly polarized dative bonds, such as amine-borane adducts, exert a strong inductive effect on adjacent C—H bonds.5 We hypothesized that Lewis/Brønsted acid complexation of nitrogen would afford nitrogen tolerance and remote site-selectivity in iron-catalyzed C(sp3)—H oxidations. Herein, we describe strategies that enable remote, non-directed aliphatic C—H oxidation in substrates containing prevalent nitrogen functional groups: amines (3°, 2°, 1°) and pyridines. Imides tolerate oxidative conditions without complexation and promote remote C(sp3)—H oxidation.

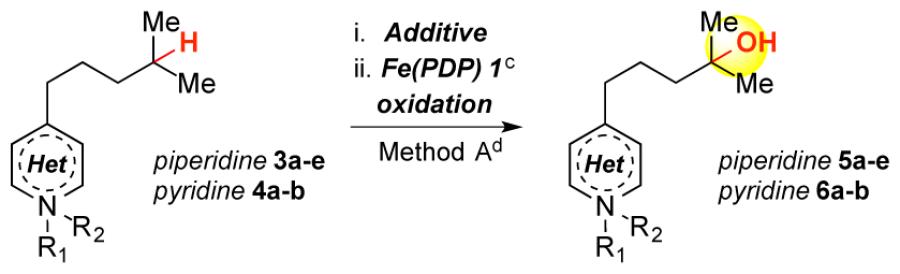

We evaluated two strategies to effect nitrogen tolerance/remote oxidation: azaphilic, oxidatively stable Lewis acid complexation with boron trifluoride (BF3) and irreversible protonation with tetrafluoroboric acid (HBF4), a strong Brønsted acid with a weakly coordinating counterion. Whereas some precedent exists with these strategies for C—H oxidations,6 olefin oxidations7a-b and metathesis,7c no examples of remote aliphatic C—H oxidations under ligated transition metal catalysis are known. In metal complexes having basic, dative ligands (e.g. PDP), competitive complexation with acid may lead to catalyst deactivation. Exploration of BF3 complexation with both 3° piperidine 3a and pyridine 4a provided encouraging yields of remotely oxidized products (Table 1, entries 1, 2). HBF4 protonation afforded remote oxidation products with improved yields for both 3a and 4a (entries 3, 7). The same protocol with tri-fluoroacetic acid or sulfuric acid,6c which generate more co-ordinating counterions, resulted in decreased yield (entry 4, 5). An in situ HBF4 protocol resulted in diminished yield of 5a, suggesting excess acid is not beneficial (entry 6). Oxidation of pyridine N-oxide 4b was unproductive (entry 8).6a

Table 1.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Entry | Heterocycle | R1 | R2 | Additive (equiv) | Yield (%) (rsm)e |

| 1 | 3a | Me | - | BF3•OEt2 (1.1) | 46 (28) |

| 2 | 4a | - | - | BF3•OEt2 (1.1) | 27 (67) |

| 3 | 3a | Me | - | HBF4•OEt2 (1.1) | 56 (29) |

| 4 | 3a | Me | - | F3CCO2H (1.1) | 5 (74) |

| 5f | 3a | Me | - | H2SO4 (1.1) | 0 (76) |

| 6g | 3a | Me | - | HBF4•H2O (1.1) | 43 (40) |

| 7 | 4a | - | - | HBF4•OEt2 (1.1) | 57 (23) |

| 8a | 4b | O | - | - | 0 (65) |

| 9a | 3b | Boc | - | - | n.d. (37) |

| 10a | 3c | TFA | - | - | n.d. (11) |

| 11 | 3d | H | - | HBF4•OEt2 (1.1) | 40 (26) |

| 12a,h | 3e | H | BF3 | - | 44 (22) |

|

| |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

| Entry | Heterocycle | R | Yield (%) (rsm)e | Selectivityj | |

|

| |||||

| 14 | 3g | Me | 57 (4) | 1:1 δ/mixture | |

| 15 | 4c | - | 53 (10) | 2.6:1 δ/γ | |

Iterative addition (3x): 5 mol% 1, AcOH (0.5 equiv), H2O2 (1.2 equiv), MeCN (ref 4a).

Slow addition: 25 mol% 2, AcOH (5.0 equiv), H2O2 (9.0 equiv), MeCN, syringe pump 6 mL/min (ref 4b,c).

c Catalyst enantiomers used interchangeably. d Method A: (i) Additive (1.1 equiv), CH2Cl2, concd in vacuo, (ii) Iterative addition, (iii) 1M NaOH.

Isolated yields, % recovered starting material (rsm).

No product observed with H2SO4 (0.55 equiv).

In situ addition of HBF4 (1.1 equiv).

2° Piperidine-BF3 complex 3e isolated and purifed. Product 5e isolated/purified as 2° piperidine-BF3 complex.

Method B: (i) HBF4•OEt2 (1.1 equiv), CH2Cl2, concd in vacuo, (ii) Slow addition, (iii) 1M NaOH.

Based on isolation.

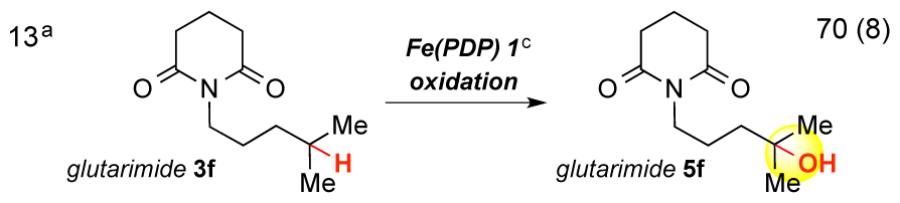

Oxidation of acyl-protected piperidines (3b-c, entries 9, 10) resulted in over-oxidized products, likely via N-dealkylation pathways. Both HBF4 protonation and BF3 complexation are effective with 2° piperidine 3d (entries 11, 12). The BF3 complexation strategy is preferable for 2° and 1° amines due to facile purification of oxidized amine-BF3 complexes. Additionally, these complexes can be stored without precaution to exclude atmosphere.8 Despite indiscriminate oxidation of carbamates and amides, we found that imides attenuate nitrogen basicity and enable remote oxidation (entry 13).

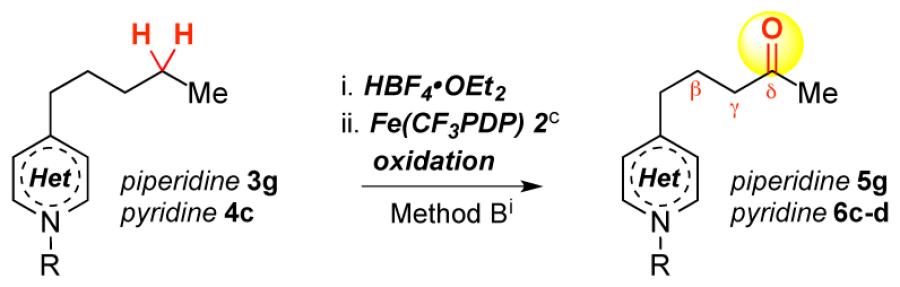

Remote methylene oxidation of piperidine 3g and pyridine 4c with Fe(CF3PDP)4c afforded good overall yields but with significantly diminished site-selectivities (Table 1, entries 14, 15). In contrast, Fe(PDP) hydroxylation of remote 3° C—H bonds proceeds with high site-selectivity; no benzylic or methylene oxidation products were detected. HBF4 protonation/oxidation of a linear substrate with competing 3° sites proceeded with excellent selectivity (>20:1 distal/proximal), favoring the site distal from the protonated amine (eq 1). Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g. Br, F, OAc) previously evaluated did not afford such strong inductive deactivation of proximal sites (9:1, 6:1, 5:1 distal/proximal, respectively).4a Collectively, these data suggest that Brønsted/Lewis acid complexation renders basic nitrogen a strong inductive withdrawing moiety, enabling remote C— H oxidations often with high site-selectivities.

Piperidines substituted at N, C4, and C2 are the most prevalent nitrogen heterocycles in drugs.1a Employing HBF4 protonation, Fe(PDP)-catalyzed tertiary oxidations of N-methyl or N-alkyl substituted piperidines proceeded uniformly in high yields and with excellent site-selectivities to afford 3° hydroxylated products (Table 2). Notably, piperi- dine 9a with C2-alkyl substitution was hydroxylated in 52% yield (10a), showcasing the effectiveness of HBF4 protonation in sterically hindered environments. Piperidines with a variety of functional groups (esters, nitriles, electron deficient aromatics) perform well under conditions where competitive hydrolysis or oxidation may occur (10b-f). The 4-phenylpiperidine motif in 10d-e represents a pharmacophore found in opioids such as ketobemidone and haloperidol.9 Improved site-selectivities for Fe(CF3PDP)-catalyzed remote methylene oxidations were observed in substrates having more electronic differentiating elements (10e and 10f, 40% and 50%, respectively).

Table 2.

Basic Aminesa

Isolated yield is average of two runs, % rsm in parentheses.

b Catalyst enantiomers used interchangeably. cMethod A with HBF4•Et2O (1.1 equiv). dMethod B. eStarting material recycled 1x. fMethod B with 1. gMethod A with BF3•Et2O (1.1 equiv) concd and purified prior to use. Isolated as BF3-complex, no NaOH workup. hMethod A with BF3•Et2O (1.1 equiv). iMethod B with BF3•Et2O (1.1 equiv) concd and purified prior to use. Isolated as BF3-complex, no NaOH workup.

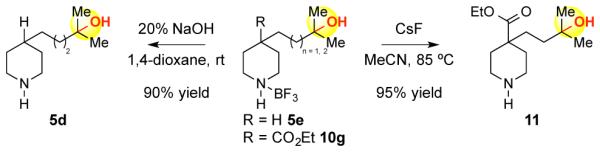

Analogous 2° piperidine-BF3 complexes worked with equal facility for remote tertiary and secondary oxidations (Table 2). Underscoring the variance in electronics between 3° and 2° C—H bonds, oxidation of 9j delivered 3° alcohol 10j in 65% yield, whereas methylene oxidation of 9k gave trace product. The BF3 complexation strategy is preferred for oxidation of sterically unencumbered 2° and 1° amines (10n), where challenges in product isolation with HBF4 protonation lead to diminished isolated yields (10l vs 10m). Protonation with HBF4 is advantageous in cases where steric hindrance at nitrogen retards effective BF3 coordination (10i 56% and 43% yield, respectively). Hydroxylated amine-BF3 complexes are readily converted to the free amine via base-mediated hydrolysis or exposure to a nucleophilic fluoride source (Scheme 1). The latter protocol is advantageous for substrates containing hydrolytically unstable functional groups, such as 10g.

Scheme 1.

Amine Deprotection Strategies

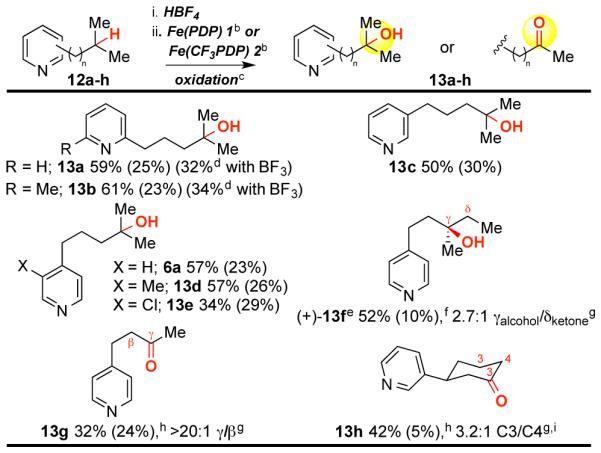

Pyridines are the most prevalent heteroaromatic in FDA approved pharmaceuticals.1a Fe(PDP)-catalyzed remote hydroxylation of 3° sites in 2-alkylpyridines proceeded smoothly using HBF4 protonation for both mono- and di-substituted substrates (13a 59%, 13b 61%, Table 3). In these sterically encumbered substrates, complexation with BF3 affords diminished yields (32% and 34%, respectively). Long-chain 3-alkylpyridines, prevalent in natural products,10 are efficiently oxidized (13c 50%). Remote oxidation proceeds in good yields with electron rich pyridines (6a, 13d) whereas yield and mass balance are lower with an electron deficient substrate (13e 34% yield, 29% recovered starting material (rsm)). Pyridines having less electronically favored and exposed 3° sites afford modest site-selectivity (13f 52%, 2.7:1). The one carbon shortened analog of 4-pentylpyridine (4c, Table 1) underwent methylene oxidation with improved site-selectivity (>20:1) but in diminished yield (13g 32% yield). In cyclohexanes4b having bulky, inductive withdrawing substituents, stereoelectronic preference for oxidation at C3 overrides electronic preference for oxidation at C4 (13h 1.6:1 C3/C4 adjusted for number of hydrogens).

Table 3.

Pyridinesa

|

Isolated yield is average of two runs, % rsm in parentheses.

bCatalyst enantiomers used interchangeably. cMethod A with HBF4•Et2O (1.1 equiv). dMethod B with BF3•OEt2 (1.1 equiv), catalyst 1 and 20% NaOH workup. e(+)−13f Refers to pure alcohol. fStarting material recycled 1x. gBased on isolation. hMethod B. i1.6:1 C3/C4 adjusted for number of hydrogens.

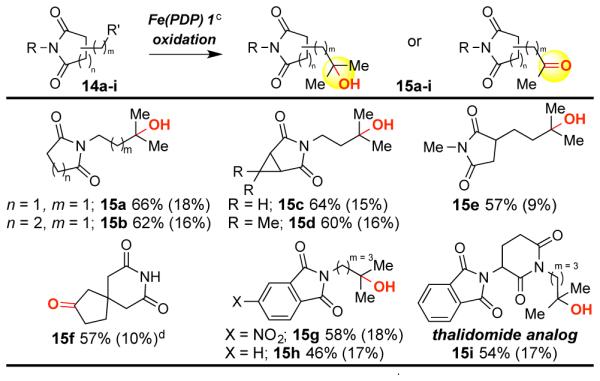

Imides are abundant in biologically active molecules and serve as synthetic precursors to amines.11 Succinimide 14a and glutarimide 14b were oxidized in excellent yield, without requirement for Brønsted/Lewis acid complexation, to afford the corresponding alcohols (Table 4). Cyclopropyl modified succinimides are tolerated in this C—H oxidation reaction (15c-d). Spirocyclic glutarimide 14f, a substructure in anxiolytic agent buspirone,12 underwent site-selective methylene oxidation in good yield (57%). Analogous to reactivity in enzymatic oxidations,1b we have observed Fe(PDP) to effect both oxidative N-dealkylation of amines and oxidation of electron neutral or rich aromatics. No N-demethylation was observed with imide 14e (57%) and both 4-nitrophthalimide 14g and unsubstituted phthalimide 14h were oxidized in useful yields (15g 58%; 15h 46%).13 Underscoring the medicinal relevance of this reaction, oxidation of thalidomide analog 14i afforded 15i in good yield (54%). Imides are oxidatively stable and inductively deactivating motifs that promote remote oxidations.

Table 4.

|

Isolated yield is average of two runs, % rsm in parentheses.

Iterative addition.

cCatalyst enantiomers used interchangeably. dStarting material recycled 1x.

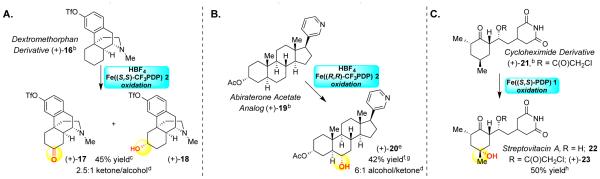

We evaluated efficacy of the aforementioned nitrogen protection strategies paired with Fe(PDP) or Fe(CF3PDP) oxidation in late-stage diversification of medicinally important complex molecules. Dextromethorphan, an antitussive drug of the morphinan class, contains a basic N-methyl piperidine moiety, an aromatic ring and a benzylic site, all highly prone to oxidation (Scheme 2A). We hypothesized that benzylic deactivation would result from the proximally fused tertiary piperidine, which as its ammonium BF4 salt would be rendered a strong inductive withdrawing group. Exposure of 16 to HBF4 protonation/Fe((S,S)-CF3PDP) oxidation afforded remote, non-benzylic oxidation products, ketone 17 and alcohol 18 in 45% yield with preference for the least sterically hindered methylene site (2.5:1 ketone/alcohol).

Scheme 2.

Late-Stage Functioalization of Nitrogen Containing Moleculesa

Abiraterone acetate, having a C17-(3-pyridyl) motif, is a steroidal antiandrogen used in the treatment of prostate cancer. Despite a strong preference for oxidation at 3° benzylic sites (BDE~83 kcal/mol),14 exposure of 19 to HBF4 protonation/Fe((R,R)-CF3PDP) oxidation resulted in a site-selective remote oxidation at C6 (BDE~98 kcal/mol) of the steroid core in 42% yield (6:1 alcohol/ketone) (Scheme 2B). These represent the first examples of transition metal catalyzed remote, aliphatic C—H oxidations on a morphinan and nitrogen-containing steroid skeletons.

Cycloheximide, a readily available natural product with broad antimicrobial activity but high toxicity is currently used as a protein synthesis inhibitor. The C4 hydroxylated analogue, streptovitacin A 22, has shown diminished toxicity and has been obtained via an eight step de novo synthesis proceeding in 7% overall yield.15 The direct oxidation of cycloheximide derivative 21 with Fe((S,S)-PDP) affords streptovitacin A derivative 23 in excellent yield (50%) (Scheme 2C), underscoring the power of remote late stage C—H oxidation to streamline synthesis.

We have demonstrated remote Fe(PDP)-catalyzed oxidation in a range of nitrogen heterocycles by employing Brønsted/Lewis acid complexation strategies. We envision this will be a highly enabling methodology for the generation of medicinal agents via late-stage oxidation and for the evaluation of their metabolites.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank G. Snapper for initial investigations, J. Griffin, J. Zhao and T. Osberger for spectra inspection, C. Delaney for checking procedures, Dr. L. Zhu for assistance with NMR data analysis, Dr. J. Bertke and Dr. D. Gray for crystallographic data and analysis. We thank Zoetis for an unrestricted grant to explore C—H oxidations in pharmaceuticals.

Funding Sources

Financial support was provided by the NIH/NIGMS (GM 112492).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:10257. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) White MC. Science. 2012;335:807. doi: 10.1126/science.1207661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nam W, Lee Y-M, Fukuzumi S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:1146. doi: 10.1021/ar400258p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Campos KR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Catino AJ, Nichols JM, Nettles BJ, Doyle MP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5648. doi: 10.1021/ja061146m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Condie AG, González-Gómez JC, Stephenson CRJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1464. doi: 10.1021/ja909145y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hari DP, König B. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3852. doi: 10.1021/ol201376v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Noble A, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11602. doi: 10.1021/ja506094d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) He J, Hamann LG, Davies HML, Beckwith RE. J. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:5943. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) McNally A, Haffemayer B, Collins BSL, Gaunt MJ. Nature. 2014;510:129. doi: 10.1038/nature13389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chan KSL, Wasa M, Chu L, Laforteza BN, Miura M, Yu J-Q. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:146. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2007;318:783. doi: 10.1126/science.1148597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2010;327:566. doi: 10.1126/science.1183602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gormisky PE, White MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14052. doi: 10.1021/ja407388y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Anslyn EV, Dougherty DA. Modern Physical Organic Chemistry; University Science Books; California: 2006. pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]; (b) Staubitz A, Robertson APM, Sloan ME, Manners I. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:4023. doi: 10.1021/cr100105a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Malik HA, Taylor BLH, Kerrigan JR, Grob JE, Houk KN, Du Bois J, Hamann LG, Patterson AW. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:2352. doi: 10.1039/C3SC53414F. Pyridines in Pd(II)/sulfoxide allylic C—H oxidation: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Asensio G, González-Núñez ME, Bernardini CB, Mello R, Adam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:7250. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee M, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12796. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Ferrer M, Sánchez-Baeza F, Messeguer A, Diez A, Rubiralta M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995:293. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brennan MB, Claridge TDW, Compton RG, Davies SG, Fletcher AM, Hen-stridge MC, Hewings DS, Kurosawa W, Lee JA, Roberts PM, Schoonen AK, Thomson JE. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:7241. doi: 10.1021/jo3010556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Woodward CP, Spiccia ND, Jackson WR, Robinson AJ. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:779. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03716h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampe EM, Rudkevich DM. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:9619. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman DM, Nickander R, Horng JS, Wong DT. Nature. 1978;275:332. doi: 10.1038/275332a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Hagan D. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1997;14:637. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ren MZ, Onat F. CNS Drug Rev. 2007;13:224. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y-H, Rayburn JW, Allen LE, Ferguson HC, Kissel JW. J. Med. Chem. 1972;15:477. doi: 10.1021/jm00275a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt VA, Quinn RK, Brusoe AT, Alexanian EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14389. doi: 10.1021/ja508469u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo Y-R, Cheng J-P. Haynes WM, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry & Physics. (94th) :9–65. CRC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo H, Oritani T, Yamashita K. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1990;54:1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.