Abstract

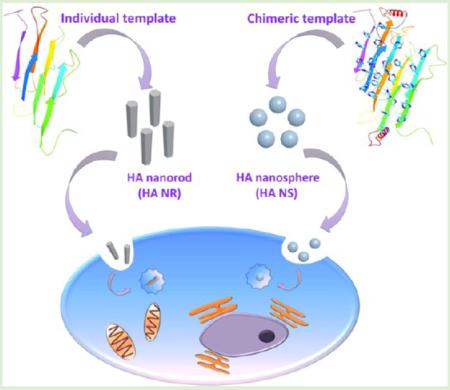

Protein-mediated molecular self-assembly has become a powerful strategy to fabricate biomimetic biomaterials with controlled shapes. Here we designed a novel chimeric molecular template made of two proteins, silk fibroin (SF) and albumin (ALB), which serve as a promoter and an inhibitor for hydroxyapatite (HA) formation, respectively, to synthesize HA nanoparticles with controlled shapes. HA nanospheres were produced by the chimeric ALB-SF template, whereas HA nanorods were generated by the SF template alone. The success in controlling the shape of HA nanoparticles allowed us to further study the effect of the shape of HA nanoparticles on the fate of rat mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). We found that the nanoparticle shape had a crucial impact on the cellular uptake and HA nanospheres were internalized in MSCs at a faster rate. Both HA nanospheres and nanorods showed no significant influence on cell proliferation and migration. However, HA nanospheres significantly promoted the osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs in comparison to HA nanorods. Our work suggests that a chimeric combination of promoter and inhibitor proteins is a promising approach to tuning the shape of nanoparticles. It also sheds new light into the role of the shape of the HA nanoparticles in directing stem cell fate.

1. INTRODUCTION

Protein template-induced molecular biomimetics through bottom-up self-assembly is becoming more and more interesting due to its ease in preparation, low energy consumption, and potential production of various composite materials with well-defined structures.1,2 Natural bone, a characteristic biocomposite with a hierarchical architecture resulted from protein-induced self-assembly biomineralization.3 During the process of bone biomineralization, collagen molecules are hierarchically assembled into a supramolecular framework that further regulates the nucleation and growth of hydroxyapatite (HA) crystals.3 Inspired from nature, many proteins, either as promoters (i.g. collagen,4 silk fibroin5) or inhibitors (albumin,6 osteopontin,7 matrix gla protein8) of HA formation, are detected in the extracellular matrix and blood systems and have been proposed to illuminate the process of biomineralization for fabricating new bone substitutes.9 Nonetheless, most of the current studies are focused on either a single promoter or a single inhibitor to modulate the HA mineralization. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on the combination of promoter and inhibitor proteins to mediate HA formation.

So far, HA nanoparticles with spherical shapes have not been achieved because HA tends to grow along its c-axis to become rod-like, needle-like, or plate-like.10–13 In this work, we designed a new chimeric template of ALB-SF by the chemical conjunction between silk fibroin (SF) and albumin (ALB), with two distinct roles of promoting and inhibiting HA nucleation, respectively, in one system. SF, a fibrous protein capable of promoting HA formation, has been used as a commendable substitute of natural type I collagen due to their similar fibrous structure and capacity in inducing HA formation.5 In contrast, ALB as a spherical protein in blood system can inhibit HA mineralization, because it has many calcium binding sites with up to 19 sites on its imidazole group that will prevent calcium ions to integrate with phosphate.6 We hypothesize that integrating SF with ALB will generate a new chimeric molecular template with dual functions of promoting and inhibiting HA formation. In our hypothesis, the individual SF template will induce HA nucleation and growth along its long axis and eventually form nanorods. If ALB is coexisting with SF, it will interrupt the growth of HA nanocrystals along one particular direction due to its inhibitory capacity, resulting in the formation of spherical HA nanoparticles.

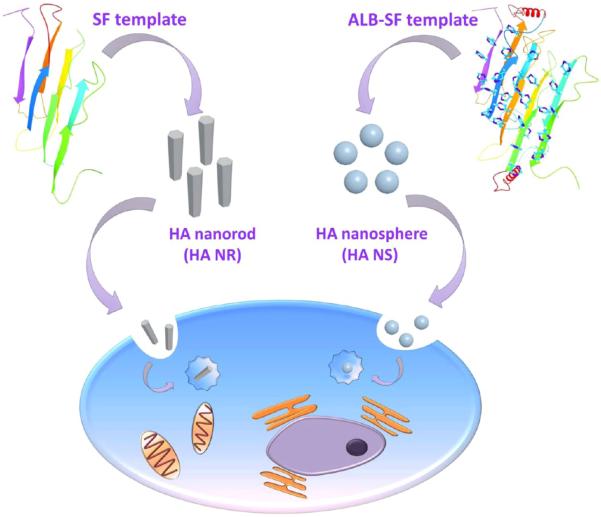

Interaction between nanoparticles and cells has been studied extensively, but little is known about the shape effect of the nanoparticles on stem cell fate.14–17 It remains a major challenge to tune their shapes with similar chemical compositions by the feasible fabrication strategies. So far, the shapes of nanoparticles made of gold,18 silica,19 zinc oxide,20 and copolymers of polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polycaprolactone (PCL),15 have been studied in terms of directing the fates of Hela cells, A375 human melanoma cells, mouse neural stem cells, and human lung-derived epithelial cells, respectively. However, the HA nanoparticles, the mineral in natural bone, have not been studied from the perspective of shape effect on the stem cell fates, due in part to the difficulty in achieving spherical HA nanoparticles. Toward this end, we first made an attempt to fabricate HA nanoparticles with two different shapes, HA nanospheres and HA nanorods, by a template-induced self-assembly method and subsequently investigated the shape effect of HA nanoparticles on directing the fate of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

General idea of this work. Two different HA nanoparticles, nanorods and nanospheres, were separately produced by a fibrous molecular template of Silk fibroin (SF) and a novel chimeric template of albumin-silk fibroin (ALB-SF), respectively. The shape effect of nanoparticles on stem cell fate was systematically studied in this work.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Synthesis of a Chimeric Template

Isolation and purification of SF were performed following our published protocol.21 Albumin (ALB) was derived from rat serum (A6414, Sigma). The ALB was cross-linked with SF to synthesize a combined protein template using N-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) approach using our previously modified protocol.22 Briefly, the carboxylic acid groups of ALB were first activated in a buffer solution of 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES buffer, 0.05 M, pH 6.0) followed by adding EDC and NHS. The molar ratio of EDC/NHS/ALB-COOH was 2:1.3:1 for the immobilization reaction. The purified SF was subsequently added to the EDC/NHS-activated ALB solution to form a stable peptide bond between the carboxylic acid group of ALB and the amide group of SF. The resultant products were lyophilized for future use and termed as a chimeric template, albumin-silk fibroin (ALB-SF).

2.2. Fabrication of Bone Nanoparticles

The template-induced self-assembly method was used to synthesize bone nanoparticles with different shapes.5 Briefly, the aforementioned chimeric protein (ALB-SF) solution (1 mg/mL, 20 mL) was mixed with Ca(NO3)2·4H2O solution (0.01M, 50 mL) under stirring for 1 h and kept at 37 °C for 12 h. The solution of (NH4)2HPO4 (0.01M, 30 mL) was dropwise added into the mixed solution. The pH value was immediately adjusted to 7.4 after completing the addition, and the suspension was maintained at 37 °C overnight. The resultant products, termed HA nanospheres, were purified and lyophilized for future use. Meanwhile, HA nanorods were produced based on the individual template of SF by our reported single-template method.5 As expected, there was no obvious HA deposition in the individual template of ALB due to the inhibition role.23–25

2.3. Characterization of Materials

The protein secondary structures of both the individual template (ALB, SF) and the chimeric template (ALB-SF) were separately analyzed using a Circular Dichroism (CD) spectrometer (J-810, Jasco, Japan), and the ellipticity spectra was measured from 190 to 250 nm. The percentages of the secondary structure for ALB, SF, and ALB-SF were calculated from the spectra using CDSSTR method.26 The zeta potential of both individual and chimeric template were investigated by a Zeta potential analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern). The crystal structure of bone nanoparticles was investigated by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, X'Pert PRO, PANalytical B.V. Holland) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å).27 The functional groups of bone nanoparticles were analyzed by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra (FTIR, Vertex 70, Bruker, Germany), in the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The atomic compositions of the samples were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, VG Multilab 2000). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and selective area electron diffraction (SAED) were performed to observe the morphology and growth orientation of the nanoparticles (FEI Tecnai G2 20). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out in air between 25 and 800 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min (Pyrisl TGA, PerkinElmer Instruments).28

2.4. Fluorescent Label of Bone Nanoparticles

Both HA nanospheres and nanorods were labeled with a red fluorescence, rhodamine B isothiocyanate (RITC) through two reactions including a coupling reaction with amino silane and a connecting reaction with RITC. Briefly, two nanoparticles were respectively suspended in the methylbenzene solution with a concentration of 20 mg/mL and, subsequently, an amino silane coupling agent, KH-550 (Sigma, A3648), was gradually added to the above nanoparticle solution with a final concentration of 0.4 mg/mL, and the reaction was maintained in room temperature for 12 h. Afterward, the rest of unreacted amino silane was removed with pure alcohol by centrifugation washing three times. The precipitation was collected and dried overnight at 50 °C for further collection reaction with RITC. Two nanoparticles coupled with amino silane were respectively suspended in the methanol solution with a concentration of 10 mg/mL, and the RITC (Sigma, 283924) was dissolved in the methanol solution with a concentration of 2 mg/mL. Subsequently, 1 mL of RITC solution was separately added to two aforementioned nanoparticle solutions. The conjugation reaction was kept at room temperature for 6 h, and the rest of unreacted RITC was removed by successively centrifugation washing with pure alcohol and tridistilled water five times, respectively. The final precipitation was collected and dried overnight at 40 °C for future use.

2.5. Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Location of Bone Nanoparticles

The rat mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were used to evaluate the interplay between nanoparticles and stem cells. The primary MSCs were isolated, purified, and cultured with our previously published protocol.5 The MSCs were first cultured with serum-free medium for 4 h, and switched to complete medium with serum prior to adding nanoparticles. To prepare the same concentration of nanoparticles, both HA nanorods and nanospheres were rinsed by suction filtration, freeze-dried, and sterilized to prepare a stocking solution of 10 mg/mL, respectively. Subsequently, both of the two stocking solutions were separately diluted to produce the working solutions with a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. Both of the two suspending solutions were respectively added to the above MSCs with an amount of 50 μL for each well. At two designed time points of 4 and 24 h, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The F-actin was stained with phalloidin labeled with FITC and the cell nuclei was stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Images of stained cells were observed with confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus, FV500). After the cells were exposed to the nanoparticle suspensions for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, ELAN DRC-e, PerkinElmer) was used to analyze the calcium concentration. Briefly, the MSCs were washed with PBS for three times to remove any residual nanoparticles. The cells were then collected, freeze-dried, and digested with 5 mL of 5% HNO3 for elemental analysis using ICP-MS. Before and after the cells were exposed to the nanoparticles, we separately prepared some cell sections for TEM observation following a published method.29 To further investigate the intracellular location of internalized nanoparticles, we used a specific endocytic indicator (pHrodo Green) that did not show fluorescence in a neutral environment (extracellular condition) while displayed a strong fluorescence in an acid intracellular environment. This indicator probe can be used to verify the nanoparticles internalized in the cell not absorbed on the outside surface of cells, and also to observe the intracellular location.

2.6. Cell Proliferation

The MSCs were incubated with nanoparticle suspensions at the designed time points of day 1, 3, 5, and 7 for measuring cell viability and proliferation by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Sigma). Briefly, the powders of HA nanospheres and nanorods were suspended in 75% ethanol for sterilization, and subsequently washed with sterile PBS five times. The MSCs were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 5000 cells/well, and then the suspensions of materials were added with a final concentration of 10 μg/mL. At a designed time point, the CCK-8 reagent was added and incubated for 12 h. The absorbance of yellow formazan was measured at 450 nm on a plate reader (BioTeck, U.S.A.).

2.7. Cell Migration

Cell migration was evaluated using a modified protocol of agarose drop.30 Briefly, we first prepared cell suspension with a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL and simultaneously fabricated a 0.3% (m/v) agarose solution using a low melting agarose. Cell suspension and agarose solution were mixed with equal volume to prepare cell-entrapped agarose drops. The drops were set in the center of the well of a 24-well culture plate, and placed at 4 °C for 15 min to solidify the agarose drop. Finally, the cell medium was added and the cells were routinely cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cell migration was monitored at the time points of 0, 4, and 24 h.

2.8. Real-Time PCR

For cell differentiation, the coculture of the cells and nanoparticles was separately terminated on days 14 and 21. Cells without nanoparticles in the absence or presence of the osteogenic media served as controls. Real-time PCR was performed using the Fastlane Cell SYBR Green Kit (Qiagen, U.S.). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from both experimental groups and control groups. Aliquots of RNA samples were initially reverse transcribed into cDNA, which was amplified with real-time quantitative PCR using gene-specific primers for osteocalcin (OCN), osteonectin (ONN), osteopontin (OPN), and collagen I (COL-I). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene. The real-time PCR reaction was done as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, 45 cycles of PCR (95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 60 s). The assay was carried out in triplicate and quantification of gene transcription was based on the relative Ct value for each sample. Sequences of the primers were used as reported in our published work.5,31

2.9. Immunofluorescence Staining

After coculture of cells and nanoparticles for 3 weeks, the cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 15 min. Each sample was permeabilized using 0.3% Triton X-100 for 5 min and then blocked with 5% BSA solution for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies targeting the osteogenic markers of OCN, ONN, OPN and COL-I. Secondary antibody of IgG-rhodamine was used to bind with the primary antibodies with 1:200 dilutions in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature, respectively. FITC-conjugated phalloidin was used to stain F-actin and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain cell nuclei. Images of the stained substrates were collected with confocal fluorescence microscope (Leica SP2MP confocal).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Analysis of CD and Zeta Potential

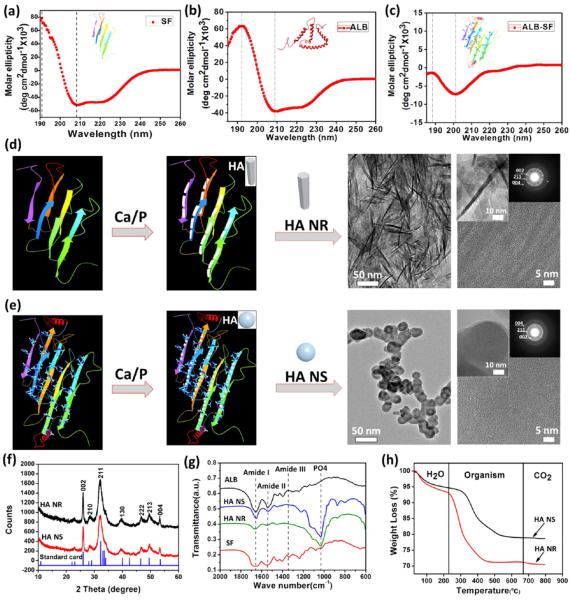

The spatial configuration of protein template, particularly β-sheet template,32 has an impact on mediating HA nucleation and growth as well as on influencing the entire properties of template-induced composite materials. We first analyzed the secondary structures of both the individual template (ALB or SF) and the chimeric template (ALB-SF) by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. The SF was found to be dominated by antiparallel β-sheet, as evidenced by a strong positive peak at around 190 nm and a negative peak at 205 nm (Figure 2a). The ALB mainly consisted of α-helix, which could be confirmed by a maximal positive peak at 192 nm and a strong negative peak at 208 nm (Figure 2b). After ALB was combined with SF, both the absorption peak and the intensity of ALB-SF were significantly changed when compared with those for individual protein templates, particularly on SF (Figure 2c). The percentages of helix and sheet in the ALB-SF were significantly increased in comparison with SF (Figure S1, Supporting Information). We found that the first positive peak (187 nm) was lower than that of ALB at the same position, whereas the second positive peak (220 nm) matched well with SF. Consequently, the major difference in the secondary structures between the chimeric template and the individual template may result from the chemical conjugation of SF and ALB. Moreover, the zeta potential of ALB and SF was found to be +28.2 and −7.45 mV, respectively. In the meantime, the zeta potential of the chimeric protein of ALB-SF turned out to be around 0 mV (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The alteration of zeta potential probably arose from the combination of most of free amide groups and carboxylic acid group into peptide bonds. Hence, the zeta potential of chimeric protein tended to be neutral as compared with individual proteins alone.

Figure 2.

Characterization of materials. (a–c) The analysis of circular dichroism showed the individual SF template was dominated by antiparallel β-sheet, whereas the individual ALB template mainly consisted of α-helix. The combined ALB-SF template presented significant changes compared with the individual templates. (d, e) HA nanorods (HA NR) and HA nanospheres (HA NS) were produced by the individual SF template and the chimeric ALB-SF template, respectively. (f) XRD analysis showed both HA NR and HA NS exhibited the main diffraction peaks of HA in comparison with HA standard card (JCPDS-PDF 09–0432). (g) FTIR analysis showed both HA NR and HA NS displayed the typical phosphate group and main functional groups of amides I, II, and III due to the presence of organic protein templates. (h) TGA analysis confirmed that both HA NR and HA NS were organic–inorganic composites consisting of ~20% organics and ~80% inorganics.

3.2. Characterization of Template-Induced Biomimetic Bone Nanoparticles

HR-TEM results showed that the HA nanorods (~50 nm in length) were induced by the individual SF templates (Figure 2d). Interestingly, the HA nanospheres with a similar size (~50 nm in diameter) were produced by the chimeric ALB-SF template (Figure 2e). Moreover, the SAED patterns were further used to evaluate the growth direction of HA crystals. It was found that there was no obvious preferential orientation according to the ring-shaped diffraction pattern from the HA nanospheres. However, HA nanorods presented the arc-shaped diffraction patterns from the (002), (211), and (004) planes, indicating the preferential orientation of HA nanorods. As expected, no obvious HA crystals were formed in the presence of another individual template, ALB. We continued to verify the formation of crystalline HA with X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Figure 2f). Both HA nanospheres and nanorods exhibited quite similar XRD patterns, which simultaneously displayed two typical stronger peaks (2θ = 25.9° for (002), 2θ = 32.8° for (211)) in comparison with the standard diffraction pattern of HA (JCPDS-PDF 09–0432). Both HA nanospheres and nanorods presented broadened diffraction peaks, confirming the nanocrystalline status of HA as in the natural bone.21

Both HA nanospheres and nanorods as well as the protein templates were investigated by Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR; Figure 2g). Two nanoparticles presented similar peaks at around 1035 cm−1, which was corresponding to the characteristic phosphate bands (PO4) in HA.33 The amide peaks of SF were shown at 1667 cm−1 (amide I), 1551 cm−1 (amide II), and 1325 cm−1 (amide III), while those of ALB were probed at 1660 cm−1 (amide I), 1544 cm−1 (amide II), and 1325 cm−1 (amide III). We found that both HA nanospheres and nanorods presented similar peaks for amide I and amide II derived from organic protein template, implying both of the bone nanoparticles were composites with inorganic HA and organic template.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was used to analyze the inorganic–organic ratio in both of two bone nanoparticles (Figure 2h). TGA curve of HA nanospheres presented a notable three-step weight loss and the total weight loss was 21.47% from 40 to 800 °C. At the first stage, the weight loss was about 6.71% due to the water evaporation from 40 to 180 °C. At the second stage, there was a major weight loss of 14.01%, which was ascribed to the combustion of the organic component. At the third stage, there was still a minor weight loss of 0.75% over 650 °C due to the decomposition of carbonated hydroxyapatite (CHA).34 There was a similar tendency in HA nanorods, which also showed a three-step weight loss. The weight loss of three stages was 7.66, 13.63, and 0.9%, respectively. The current data confirmed that the inorganic–organic ratio of two bone nanoparticles was around 20:80, which was also similar to the ratio in the natural bone matrix.35

The XPS analysis showed that both SF and ALB templates exhibited C 1s, O 1s, and N 1s. Compared with the protein templates, both HA nanorods and nanospheres displayed C 1s, O 1s, N 1s, Ca 2p, and P 2p (Figure S3, Supporting Information). In addition, the calcium-to-phosphate ratios (Ca/P) of in both HA nanorods and nanospheres were found to be approximately 1.50 and 1.57, respectively, close to the theoretical value of HA (Ca/P = 1.67).

3.3. Cellular Uptake

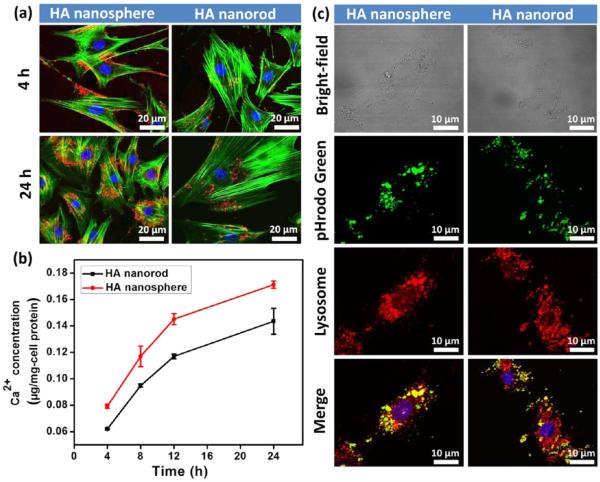

Two different bone nanoparticles, HA nanospheres and HA nanorods, were separately labeled with Rhodamine-B-Isothiocyanate (RITC) prior to studying cellular uptake. The confocal images confirmed that both HA nanospheres and nanorods were successfully internalized into MSCs by the coculture of the nanoparticles and MSCs for different times (4 and 24 h; Figure 3a). We found that the HA nanospheres entered the cells with a faster rate than the HA nanorods within the initial 4 h. After 24 h in cellular uptake, the HA nanospheres presented much more nanoparticle accumulation in the cytoplasm in comparison with the HA nanorods. ICP-MS analysis further confirmed that the calcium uptake in HA nanospheres was much higher than that in HA nanorods (Figure 3b). All of these results imply that the chimeric template-induced HA nanospheres are apt to promote cellular uptake.

Figure 3.

The shape effect of nanoparticles on cellular uptake and intracellular location. (a) Cellular uptake was evaluated in different times of 4 and 24 h. Both HA nanospheres and nanorods could be readily internalized into MSCs. The HA nanospheres showed a faster rate to enter cells and more intracellular accumulation compared with HA nanorods. The nanoparticles were labeled with RITC (red), the F-actin of cytoskeleton was stained with FITC (green), and the nuclei were stained with DAPI. (b) ICP-MS analysis showed that the calcium uptake of HA nanospheres in MSCs was higher than that of HA nanorods at different time points of 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. (c) After 24 h in cellular uptake, intracellular location of the internalized nanoparticles was investigated by a specific endocytic probe of pHrodo-green. The results showed most of nanoparticles entered the lysosomes because the merged yellow fluorescence was formed due to the overlap between green nanoparticles and red lysosomes. Nanoparticles were labeled by pHrodo (green) and the lysosomes were stained with the antibody (red).

3.4. Location of the Internalized Nanoparticles

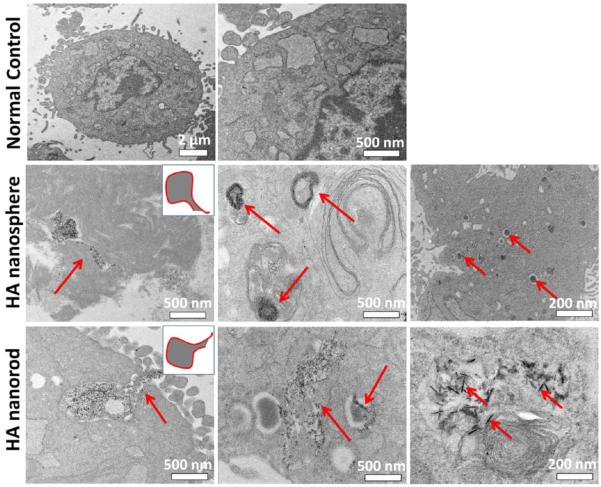

We further investigated the location of two internalized HA nanoparticles in the cytoplasm (Figure 3c). A specific intracellular indicator (pHrodo Green) was used to confirm the process of endocytosis, because this indicator probe shows no fluorescence in a neutral extracellular environment while it can turn green fluorescence in an acid intracellular environment, such as cytoplasm, particularly in lysosome. Hence, the generation of green fluorescence demonstrated two nanoparticles can be internalized into cytoplasm, not absorbed on the outside surface of cells. We also labeled the lysosomes using a specific probe of lysotracker with red fluorescence. By merging of the two different fluorescence images, arising from green nanoparticles and red lysosomes, we further validated that most of the nanoparticles were located in the lysosomes. Furthermore, TEM images of the cells before and after exposure to the nanoparticles showed that the two differently shaped nanoparticles promoted the internationalization via an endocytosis process (Figure 4). Consequently, two nanoparticles with different shapes can be taken up by MSCs via a nonspecific endocytosis, and subsequently be transported by lysosomes in the cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

Dynamic observation of cells before and after exposure to the nanoparticles. TEM images showed that both HA nanospheres and nanorods were able to be internalized into MSCs via a classic endocytosis process, transported by lysosomes, and accumulated in the cytoplasm. Two insets show the shape of a newly generated endosome during the process of endocytosis. Red arrows denoted the location of nanoparticles.

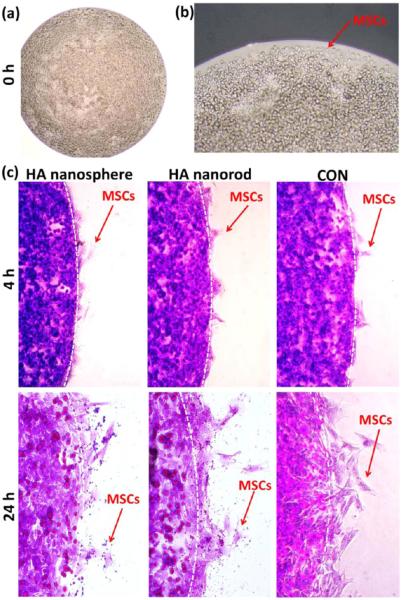

3.5. Cell Migration

Cellular uptake is expected to influence a variety of cell behaviors including cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Cell migration was evaluated by a modified cell-entrapped agarose drop method, and the results showed that all cells were first trapped in the agarose drop, and initially, no cells could migrate over the drop edge (Figure 5a,b). After 4 h in cell culture, some cells successfully migrated over the edge line, and spread to form polygonal cell morphologies. After 24 h in cell culture, more and more cells migrated from agarose drop and there was no significant difference between experimental and control groups (Figure 5c). Consequently, these results demonstrate that both HA nanospheres and nanorods did not obviously affect cell migration.

Figure 5.

Shape effect of nanoparticles on cell migration at different time points of 0 (a, b), 4, and 24 h (c). The results showed both HA nanospheres and nanorods did not obviously affect cell migration, and there was no significant difference before and after nanoparticles uptake by MSCs. The cells were stained with crystal violet.

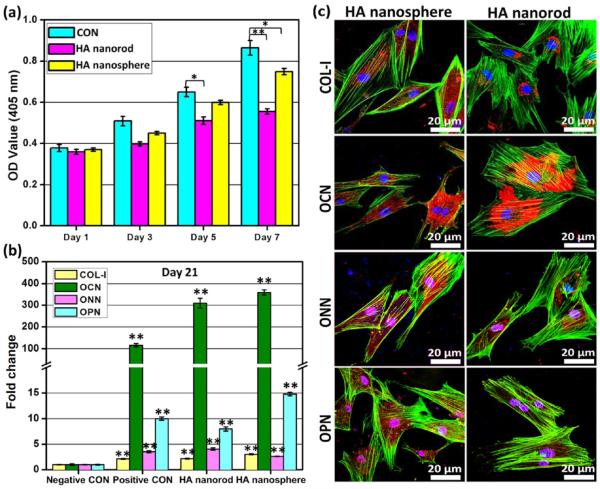

3.6. Cell Proliferation

The effects of HA nanospheres and nanorods on cell proliferation were further investigated through the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Figure 6a). The uptake of these two nanoparticles did not cause obvious toxicity. No significant difference was found between the two nanoparticles from day 1 to day 7. Conversely, from day 5 to day 7, the experimental groups (nanoparticle uptake) showed a slight decline in comparison with the control (no nanoparticle uptake). Based on our31 and other previous studies,31,36 such a slight decrease of cell proliferation at the later time is probably due to the initiation of cell differentiation.

Figure 6.

Shape effect of nanoparticles on cell proliferation and differentiation. (a) Cell proliferation showed that both HA nanospheres and nanorods exhibited excellent biocompatibility, presented no obvious toxicity, and were able to well support cell proliferation over the time. (b) Real-time PCR showed both nanoparticles significantly enhanced osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs based on the analysis of specific osteogenic genes including osteocalcin (OCN), osteonectin (ONN), osteopontin (OPN), and collage I (COL-I) on Day 21. The HA nanospheres showed stronger osteogenic capacity than HA nanorods. (c) Immunofluorescence staining showed that all corresponding proteins of osteogenic genes exhibited positive staining, and the results were highly consistent with mRNA level in (b). OCN, ONN, OPN, and COL-I were stained by rhodamine-labeled antibody (red), cell nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue), and F-actin were stained by FITC-labeled phalloidin (green).

3.7. Cell Differentiation

We continued to study the effect of two nanoparticles on osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs. Real-time PCR was used to analyze the relative fold changes of osteogenic genes including osteocalcin (OCN), osteonectin (ONN), osteopontin (OPN), and collagen I (COL-I) at two time points of day 14 and day 21. Compared with the positive control (cell culture in osteogenic medium) and the negative control (cell culture in basal medium), we found that both HA nanospheres and nanorods significantly promoted the osteoblastic differentiation, and the differentiation level was significantly enhanced over the time from day 14 (Figure S5, Supporting Information) to day 21 (Figure 6b). Also, the HA nanospheres showed a maximal value on both OCN and OPN on both day 14 and day 21, suggesting that the HA nanospheres showed better osteogenic capacity than the HA nanorods. Immunofluorescence staining, which serves as a qualitative analysis at the protein level, was further used to verify the differentiation status on Day 21. All osteogenic markers including OCN, ONN and OPN and COL-I exhibited significant positive staining (Figure 6c). All markers also showed high expressions in the positive control (Figure S6, Supporting Information). Overall, the result of immunofluorescence staining is highly consistent with the analysis of gene transcription. Therefore, we can conclude that MSCs can be successfully induced to differentiate into the bone cell lineage due to the stimulation of HA nanospheres and nanorods, and the former showed stronger inductive capacity than the latter under the same condition.

4. DISCUSSION

Mineralized tissues such as bone and dentin are unique biocomposites with excellent properties by combining the structural organic matrix with matrix-induced apatite crystals.1,14,37 Inspired from this fact, a specific strategy of protein template-induced self-assembly has been suggested to use the existing matrix protein or new designed proteins/peptides as templates to mediate the formation of inorganic crystals for generating new bone substitutes.2,38,39 In this work, we, for the first time, designed a novel chimeric molecular template with dual roles of promoting and inhibiting HA crystal formation and finally achieved spherical HA nanoparticles based on the induction of this unique chimeric template. A possible formation mechanism of HA nanospheres is suggested based on our current results. In general, the HA crystals can be grown preferentially along its c-axis to form a long rod-like morphology due to the induction by the promoter, the SF (Figure 2d).5,21 However, such preferential crystal growth will be suddenly interrupted due to the presence of an inhibitor, ALB, under the condition of the chimeric template. As a result, a novel HA with spherical morphology is generated due to the synergistic effect of this well-designed chimeric template with dual functions of promoting and inhibiting HA formation (Figure 2e). Overall, our findings clearly demonstrate that the shapes of template-induced inorganic crystals are highly dependent on the structures and properties of molecular templates.32,39,40

It is well documented that several nanoparticle factors such as size, surface chemistry and shape can influence the interaction between nanoparticles and cells. Previous studies have clearly demonstrated that sphere-shaped nanoparticles have a higher capacity of entering the cells in comparison with rod-shaped nanostructures.18 Similarly, our current data also demonstrate that both HA nanospheres and nanorods can be readily internalized into MSCs, and HA nanospheres can enter the cells with a faster rate in the initial time and a greater amount in the end than HA nanorods (Figures 3 and S4, Supporting Information). The difference in the protein molecular templates (chimeric and individual template) may slightly affect cell uptake due to the neutral surfaces of both HA nanospheres and nanorods (Figure S7, Supporting Information). More importantly, the shape effect of nanoparticles plays a crucial role on cellular uptake. A previous study has confirmed that the long rod-shaped nanoparticles will cause disorder in the organization of the cytoskeleton when taken up into cells, whereas the sphere-shaped nanoparticles do not disrupt the cell cytoskeleton.41 Hence, a possible explanation for our findings is that the HA nanospheres will slightly affect the disorder of cell cytoskeleton and result in a quick cytoskeleton reorganization, and eventually, they can enter the cells faster. On the contrary, the HA nanorods will seriously destroy cytoskeleton to cause a significant reorganization of cytoskeleton that will delay this internalization process and finally cause relatively slower rate of uptake (Figure S8, Supporting Information).

Cellular uptake will govern a range of other cell behaviors including cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Our results demonstrate that both HA nanospheres and nanorods show no significant influence on cell migration (Figure 5) and cell proliferation (Figure 6a) but significantly enhance the directed osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs (Figure 6b,c). Since all chemical components of two nanoparticles show excellent biocompatibilities, there is no toxicity for cell growth and proliferation. There will also be no adverse effect on cell migration because the cell migration highly associated with cell proliferation exhibits a normal increasing tendency. The positive role of two bone nanoparticles in inducing osteogenic maturation is mainly through the uptake of Ca2+, because the osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs is accompanied by the expression of Ca2+, binding proteins in the extracellular matrix.42 The signaling pathway of ossification tends to be enhanced with the existence of an enormous source of Ca2+. Hence, HA nanospheres have higher osteogenic capacity than HA nanorods because the spherical nanoparticles enter the cells with a relatively faster rate and in larger amounts and can initiate osteogenic differentiation at an early time.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we first designed a novel chimeric template with dual roles of promoting and inhibiting HA formation to control the shape of HA crystals. As a result, HA nanoparticles with two distinct shapes, nanospheres and nanorods, were synthesized due to the induction of the chimeric template and the individual template, respectively. Two nanoparticles can be considered as bone substitutes because they are quite close to natural bone in terms of the crystalline structure, chemical composition, and inorganic–organic ratio. Both nanoparticles could be readily internalized into cells with the HA nanosphere at a faster rate and in a larger amount. Moreover, the uptake of two nanoparticles by MSCs did not obviously affect cell migration and proliferation. Importantly, both nanoparticles significantly enhance the osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs. The HA nanospheres show stronger osteogenic capacity than the HA nanorods. Consequently, our current study provides a feasible protocol to synthesize HA nanoparticles with controlled shapes and shed light into the role of their shapes in directing the fate of MSCs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Key Project of NSFC (31430029) and NSFC (81461148032, 81471792, and 30870624), the National Basic Research Program of China (2012CB933601). We are also grateful for the Analytical and Testing Center of HUST. J.L.W., Y.Z., and C.B.M. would like to thank the financial support from National Institutes of Health (EB015190 and HL092526), National Science Foundation (CBET-0854465, CMMI-1234957, CBET-0854414, and DMR-0847758), Department of Defense Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-12-1-0384), Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research (434003), and Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR14-160).

Footnotes

Supporting Information The percentage of protein secondary structure, zeta potential analysis of individual protein templates and chimeric protein templates, XPS analysis, the analysis of Z-stack 3D reconstruction, real-time PCR analysis in the time point of 14 days, fluorescence staining of positive control (osteogenic medium) on day 21, zeta potential of HA nanospheres and nanorods, and schematic mechanism for the shape effect of nanoparticles on cytoskeletons. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00419.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sarikaya M, Tamerler C, Jen AKY, Schulten K, Baneyx F. Molecular biomimetics: nanotechnology through biology. Nat. Mater. 2003;2(9):577–585. doi: 10.1038/nmat964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Tamerler C, Sarikaya M. Genetically designed peptide-based molecular materials. ACS Nano. 2009;3(7):1606–1615. doi: 10.1021/nn900720g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Olszta MJ, Cheng XG, Jee SS, Kumar R, Kim YY, Kaufman MJ, Douglas EP, Gower LB. Bone structure and formation: A new perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. 2007;58(3–5):77–116. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Cui FZ, Li Y, Ge J. Self-assembly of mineralized collagen composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. 2007;57(1–6):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wang J, Yang Q, Mao C, Zhang S. Osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on the collagen/silk fibroin bi-template-induced biomimetic bone substitutes. J. Biomed Mater. Res. A. 2012;100(11):2929–2938. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Rees SG, Wassell DTH, Shellis RP, Embery G. Effect of serum albumin on glycosaminoglycan inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation. Biomaterials. 2004;25(6):971–977. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pampena DA, Robertson KA, Litvinova O, Lajoie G, Goldberg HA, Hunter GK. Inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by osteopontin phosphopeptides. Biochem. J. 2004;378:1083–1087. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Goiko M, Dierolf J, Gleberzon JS, Liao YY, Grohe B, Goldberg HA, de Bruyn JR, Hunter GK. Peptides of matrix gla protein inhibit nucleation and growth of hydroxyapatite and calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals. PLoS One. 2013;8:11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hunter GK, Hauschka PV, Poole AR, Rosenberg LC, Goldberg HA. Nucleation and inhibition of hydroxyapatite formation by mineralized tissue proteins. Biochem. J. 1996;317:59–64. doi: 10.1042/bj3170059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).He T, Abbineni G, Cao B, Mao CB. Nanofibrous bio-inorganic hybrid structures formed through self-assembly and oriented mineralization of genetically engineered phage nanofibers. Small. 2010;6(20):2230–5. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wang F, Cao B, Mao CB. Bacteriophage bundles with pre-aligned ca initiate the oriented nucleation and growth of hydroxylapatite. Chem. Mater. 2010;22(12):3630–3636. doi: 10.1021/cm902727s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yang M, Shuai Y, Zhang C, Chen Y, Zhu L, Mao CB, OuYang H. Biomimetic nucleation of hydroxyapatite crystals mediated by Antheraea pernyi silk sericin promotes osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(4):1185–93. doi: 10.1021/bm401740x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Yang M, Zhou G, Shuai Y, Wang J, Zhu L, Mao CB. Ca2+-induced self-assembly of Bombyx mori silk sericin into a nanofibrous network-like protein matrix for directing controlled nucleation of hydroxylapatite nano-needles. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2015;3:2455–2462. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01944J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Nudelman F, Pieterse K, George A, Bomans PHH, Friedrich H, Brylka LJ, Hilbers PAJ, de With G, Sommerdijk NAJM. The role of collagen in bone apatite formation in the presence of hydroxyapatite nucleation inhibitors. Nat. Mater. 2010;9(12):1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmat2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Geng Y, Dalhaimer P, Cai SS, Tsai R, Tewari M, Minko T, Discher DE. Shape effects of filaments versus spherical particles in flow and drug delivery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2007;2(4):249–255. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Xie J, Lee S, Chen XY. Nanoparticle-based theranostic agents. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62(11):1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wang J, Wang L, Yang M, Zhu Y, Tomsia A, Mao C. Untangling the effects of peptide sequences and nanotopographies in a biomimetic niche for directed differentiation of iPSCs by assemblies of genetically engineered viral nanofibers. Nano Lett. 2014;14(12):6850–6856. doi: 10.1021/nl504358j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Lett. 2006;6(4):662–668. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Huang XL, Teng X, Chen D, Tang FQ, He JQ. The effect of the shape of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on cellular uptake and cell function. Biomaterials. 2010;31(3):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Deng XY, Luan QX, Chen WT, Wang YL, Wu MH, Zhang HJ, Jiao Z. Nanosized zinc oxide particles induce neural stem cell apoptosis. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:11. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/11/115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wang J, Zhou W, Hu W, Zhou L, Wang S, Zhang S. Collagen/silk fibroin bi-template induced biomimetic bone-like substitutes. J. Biomed Mater. Res. A. 2011;99A(3):327–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wang J, Hu W, Liu Q, Zhang S. Dual-functional composite with anticoagulant and antibacterial properties based on heparinized silk fibroin and chitosan. Colloids Surf., B. 2011;85(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hughes Wassell DT, Hall RC, Embery G. Adsorption of bovine serum albumin onto hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials. 1995;16(9):697–702. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)99697-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liu TY, Chen SY, Liu DM, Liou SC. On the study of BSA-loaded calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite nano-carriers for controlled drug delivery. J. Controlled Release. 2005;107(1):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Serro AP, Bastos M, Pessoa JC, Saramago B. Bovine serum albumin conformational changes upon adsorption on titania and on hydroxyapatite and their relation with biomineralization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2004;70A(3):420–427. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Sreerama N, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: Comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 2000;287(2):252–260. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rogers KD, Daniels P. An X-ray diffraction study of the effects of heat treatment on bone mineral microstructure. Biomaterials. 2002;23(12):2577–2585. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gross KA, Gross V, Berndt CC. Thermal analysis of amorphous phases in hydroxyapatite coatings. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1998;81(1):106–112. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gratton SE, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105(33):11613–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Xu Z, Shen MX, Ma DZ, Wang LY, Zha XL. TGF-beta 1-promoted epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation and cell adhesion contribute to TGF-beta 1-enhanced cell migration in SMMC-7721 cells. Cell Res. 2003;13(5):343–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wang J, Wang L, Li X, Mao C. Virus activated artificial ECM induces the osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells without osteogenic supplements. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1242. doi: 10.1038/srep01242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).He G, Dahl T, Veis A, George A. Nucleation of apatite crystals in vitro by self-assembled dentin matrix protein, 1. Nat. Mater. 2003;2(8):552–558. doi: 10.1038/nmat945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Yao J, Tjandra W, Chen YZ, Tam KC, Ma J, Soh B. Hydroxyapatite nanostructure material derived using cationic surfactant as a template. J. Mater. Chem. 2003;13(12):3053–3057. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Landi E, Celotti G, Logroscino G, Tampieri A. Carbonated hydroxyapatite as bone substitute. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2003;23(15):2931–2937. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Weiner S, Wagner HD. The material bone: Structure mechanical function relations. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998;28:271–298. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Tare R, Andar A, Riehle MO, Herzyk P, Wilkinson CDW, Oreffo ROC. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat. Mater. 2007;6(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Wang J, Yang M, Zhu Y, Wang L, Tomsia AP, Mao C. Phage Nanofibers Induce Vascularized Osteogenesis in 3D Printed Bone Scaffolds. Adv. Mater. 2014;26(29):4961–4966. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science. 2001;294(5547):1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Prozorov T, Mallapragada SK, Narasimhan B, Wang L, Palo P, Nilsen-Hamilton M, Williams TJ, Bazylinski DA, Prozorov R, Canfield PC. Protein-mediated synthesis of uniform superparamagnetic magnetite nanocrystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007;17(6):951–957. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wang X, Zhuang J, Peng Q, Li YD. Liquid-solid-solution synthesis of biomedical hydroxyapatite nanorods. Adv. Mater. 2006;18(15):2031–+. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Huang XL, Li LL, Liu TL, Hao NJ, Liu HY, Chen D, Tang FQ. The shape effect of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on biodistribution, clearance, and biocompatibility in vivo. ACS Nano. 2011;5(7):5390–5399. doi: 10.1021/nn200365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).An SF, Gao Y, Ling JQ, Wei X, Xiao Y. Calcium ions promote osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human dental pulp cells: implications for pulp capping materials. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2012;23(3):789–795. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.