Abstract

The effect of cations in the surrounding solutions on the surface degradation of magnesium alloys, a well-recognized biodegradable biomaterial, has been neglected compared with the effect of anions in the past. To better simulate the compressive environment where magnesium alloys are implanted into the body as a cardiovascular stent, a device is designed and employed in the test so that a pressure, equivalent to the vascular pressure, can be directly applied to the magnesium alloy implants when the alloys are immersed in a medium containing one of the cations (K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) found in blood plasma. The surface degradation behaviors of the magnesium alloys in the immersion test are then investigated using hydrogen evolution, mass loss determination, electron microscopy, pH value, and potentiodynamic measurements. The cations are found to promote the surface degradation of the magnesium alloys with the degree decreased in the order of K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. The possible mechanism of the effects of the cations on the surface degradation is also discussed. This study will allow us to predict the surface degradation of magnesium alloys in the physiological environment and to promote the further development of magnesium alloys as biodegradable biomaterials.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The biodegradability and low toxicity of magnesium (Mg) and its alloys enable them to become a promising candidate as implantable materials used in medical devices. Clinical studies as well as in vivo and in vitro assessments have demonstrated that Mg alloys are relatively biosafe.1–3 Mg-based implants could be absorbed after their missions to avoid secondary surgeries and alleviate suffering in patients. However, Mg and its alloys degrade so rapidly that they cannot support blood vessel walls or fractured bones for an adequate time during the healing process in blood plasma or human body fluids.1 Hence, identifying and understanding the biological features and material factors that govern the surface degradation (corrosion) kinetics and mechanisms are of significant importance to promote the development of biodegradable stents. It has been reported that the corrosion behaviors of Mg alloys are predominately affected by the environment.4–6 To understand the corrosion mechanism of Mg alloys, previous researchers used various solutions, such as Hank’s balanced salt solution,7,8 simulated body fluid (SBF),9,10 and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM),11,12 to study the corrosion behavior of Mg alloys. Additionally, the influences of anions, including chloride (Cl−),6,10 hydrogen carbonate (HCO32−),4,6,13,14 and hydrogen phosphate (HPO43−),10,15 on the corrosion of Mg alloys have been investigated. Although the concentrations of metal cations in the physiological environment cannot be ignored,16 little attention has been paid to the influences of metal cations on the corrosion behavior. Nevertheless, it was reported that metal cations, such as Mg2+, Ca2+, and Na+, can affect the corrosion behavior of metals under atmospheric conditions.17–19 For a more comprehensive understanding of the degradation behavior of Mg alloys, it is necessary to investigate the corrosion properties of Mg alloys in the presence of different metal cations found in the physiological environment.

This study aimed to identify the influence of four main metal cations found in blood plasma, including Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ ions, on the surface degradation of Mg alloys by the standard immersion test and electrochemical approaches.20 To avoid interference from anions, two types of anionic system were used to compare the influences of these four metal cations (Table 1). Chloride ions were reported to have a strong promoting effect on the corrosion of Mg alloys,4,10 while hydrogen phosphate and dihydrogen phosphate ions were observed to retard the corrosion process.6 To simulate the environment of blood vessels, the concentration of metal cations in the designed solutions were kept the same as that of Na+ in blood plasma. Given the influence of pressure on magnesium corrosion,21 to better simulate the blood vessel environment, samples were loaded with stress to simulate the compressive environment of implantation. Hence, a special experimental device was designed and employed [Figure S1, Supporting information (SI)] to ensure that each Mg alloy sample was under a pressure equivalent to vascular pressure, because cardiovascular stents will be exposed to a compressive environment after being implanted into blood vessels.

Table 1.

Ionic Composition and Concentration (in mM) of Each Test Solution

| solutions | concentration

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Cl− | HPO42− | |

| blood plasma20 | 142.0 | 5.0 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 103.0 | 1.0 |

| 1 (NaCl) | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 142.0 | 0 |

| 2 (KCl) | 0 | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 142.0 | 0 |

| 3 (MgCl2) | 0 | 0 | 142.0 | 0 | 284.0 | 0 |

| 4 (CaCl2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 142.0 | 284.0 | 0 |

| 5 (Na2HPO4) | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 71.0 |

| 6 (K2HPO4) | 0 | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 71.0 |

| 7 (NaH2PO4) | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 71.0 |

| 8 (KH2PO4) | 0 | 142.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 71.0 |

| 9 [Ca(H2PO4)2] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 142.0 | 0 | 142.0 |

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1. Materials

Rolled Mg alloy (AZ31B) samples (nominal composition: Al, 0.005; Mn, 0.019; Zn, 0.008; Si, 0.01; Cu, 0.003; Fe, 0.049; Ni, 0.0001; balanced with Mg) were supplied by Shanxi Jinhui Science and Technology Co., Ltd., with a size of 20 × 5 × 2 mm3 (see Figure S2, SI). For the electrochemical, immersion, and evolution tests, the samples were made rectangular and polished with SiC abrasive paper of 400, 1000, and 3000 grits sequentially. After being polished, the samples were successively cleaned in an ultrasonic bath of acetone, alcohol, and distilled water each for 5 min and then rinsed with distilled water and dried by nitrogen gas. The final thickness was adjusted to 1.9 mm after being polished.

2.2. Hydrogen Evolution, pH Measurement, and Weight Loss Analysis

Immersion tests were carried out in nine various aqueous solutions (Table 1) and in a carefully designed acrylic reaction container (Figure S1, SI) with a pressure of 100 mmHg applied to the Mg alloys. The container was placed in a digitally controlled water bath maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C for 7 days to compare corrosion degree in each solution. The volume of hydrogen gas released during the immersion depended on the dissolution of Mg as explained below.

The anodic and cathodic reaction proceeded as follows, respectively:22

| (1) |

| (2) |

Thus, the total reaction after the combination of the above two reactions can be described as

| (3) |

Therefore, the corrosion rate of Mg can be monitored by the volume of hydrogen evolved per unit time in unit area. The hydrogen evolution rate (HER) is expressed as23

| (4) |

where S is the exposed area, t is the immersion time, and V is the volume of hydrogen evolution.

Monitoring the pH values in chemical and biological environments is critical. The pH value steadily increased during the dissolution of magnesium according to reaction 2. The change in the pH value of the solutions during the immersion depended on the dissolution of Mg. The immersion test was carried out at different time points to monitor the local pH values of samples, which were immersed in 40 mL of various solutions in accordance with the G31-72 standard of the American Society for Testing and Materials (the ratio of surface area to solution volume was 1 cm2:20 mL).24 At different time points (i.e., 1–6 and 12 h; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 d), the pH values of the material surface were measured at three random locations on each sample using a flat membrane microelectrode (MI-406, Microelectrodes, Bedford, NH) with a separate reference electrode (MI-401, Microelectrodes).25 This pH meter was calibrated before each measurement. Three samples were measured for each test. In addition, the release of magnesium ions from the samples both in the solution and on the surface were measured at four different time points (i.e., 1, 3, 5, and 7 d) using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (Optical Emission Spectrometer, PerkinElmer, Optima 2100DV). The correlation between ion dissolution and time was subsequently established.

Each sample was weighed before being immersed in solutions. The corrosion product that formed on the sample surface during corrosion was removed by immersing the samples into chromic acid (200 g/L CrO3 + 10 g/L AgNO3) for 5 min26 and subsequently rinsing the samples with running distilled water and drying under vacuum. The weight of the samples before and after being soaked was recorded to calculate the mass loss and corrosion rate of samples immersed in different solutions. The weight of five parallel samples was measured in each solution to determine the average values and standard deviations. The degradation rate was calculated by eq 5

| (5) |

where m0 is the weight before degradation (g), m1 is the weight after degradation (g), s is the degraded area (cm2), and t is the soaking time (h).

2.3. Surface Morphology Analysis

The samples were removed after 7 days of immersion in various solutions and ultrasonically cleaned in acetone solution. The morphologies and structures of corrosion products on the sample surface were examined using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; Merlin, Zeiss, Germany). Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) was employed to analyze the elementary composition of corrosion products.

2.4. Electrochemical Test

An electrochemical test was conducted to evaluate the corrosion potentials of AZ31B Mg in various solutions. Its corrosion resistance was characterized by Zennium electrochemical workstations (Zahner Electric Co.). A three-electrode system was used, which was made of a working electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as a reference electrode, and a platinum plate as the auxiliary electrode. All the electrochemical tests were carried out at a temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C throughout testing. Prior to polarization, the samples were immersed in 500 mL of solution for 15 min. The polarization scan started from −1.5 V at a scan rate of 3 mV/s, and the changes in the free corrosion potential (Ecorr) were monitored as a function of time. The samples were measured in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed on hydrogen evolution, pH change, mass loss, and release of Mg ions using SPSS v19.0.0 (IBM) software to determine whether a significant difference exists (p < 0.05) between groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Influence of Various Cations on the Hydrogen Evolution, Solution pH, and Weight Loss of Samples

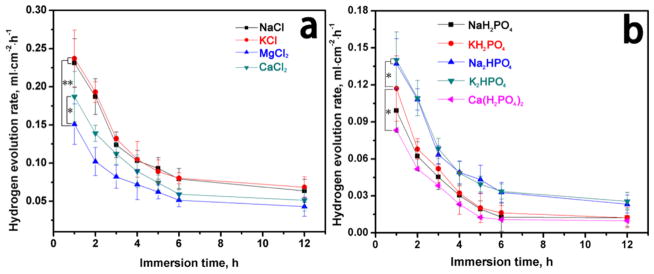

The HERs for the AZ31B alloys (Figure 1) were found to be dependent on the cations. The HERs decreased as the immersion time prolonged and finally leveled off, which might result from the formation of the layer of corrosion products on the surface of the alloys. Generally, the HERs were lower in dihydrogen phosphate solutions and hydrogen phosphate solutions than in the chlorine solutions. At concentrations the same as those in the blood, the metal cations influenced the HERs. The HERs were higher in solutions 1–4 than that in solutions 5–9. In solution 3, the existence of Mg ions inhibited Mg2+ releasing from Mg surface (reaction 1); thus, the HER of solution 3 was the lowest in chlorine solutions. When the metal cations were calcium ions in the solutions, the formation of the corrosion product film affected the HERs.

Figure 1.

Hydrogen evolution for AZ31B alloys in different solutions: (a) solutions 1–4 and (b) solutions 5–9. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

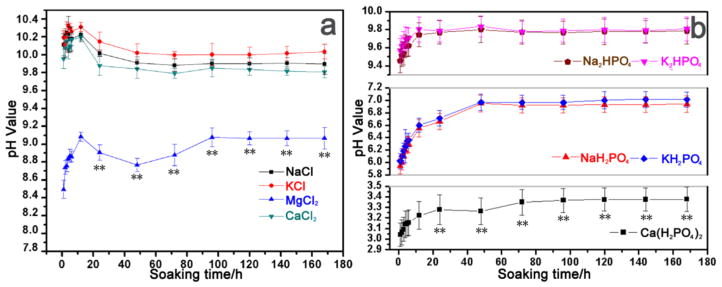

The variations in the pH value during the immersion tests (n = 5) in each solution are shown in Figure 2. The pH values of solutions 1–4 increased abruptly after 12 h of immersion, followed by a drop (Figure 2a). This result was attributed to the dissolution of Mg and the subsequent formation of Mg hydroxide. When chloride ions were present, the degradation rates of AZ31B alloys were greatly accelerated. After a period of reduction, the pH value slowly increased with further immersion time and finally became steady. Obviously, the pH change rates and equilibrium values were different according to the type of metal cations present in the solutions. Reaction 1 was inhibited when there was Mg2+ ions present as shown in Figure 1a. Due to the inhibiting effect of the hydrogen phosphate and dihydrogen phosphate ions, the pH value of solutions 5–9 increased slowly when compared with solutions 1–4. Apparently, when Na+ existed in the solutions (i.e., solutions 1 and 5), the pH values were higher than for other solutions. In solution 3, the presence of Mg2+ inhibited the reaction between Mg and the solution. The curves of solution 1, 2, and 4 showed that the degradation degree of the Mg alloys was much smaller in the presence of Ca2+.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the soaking time and the pH values in different solutions of AZ31B alloys at 37 °C: (a) solutions 1–4 and (b) solutions 5–9. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5). **p < 0.01 compared to all other groups.

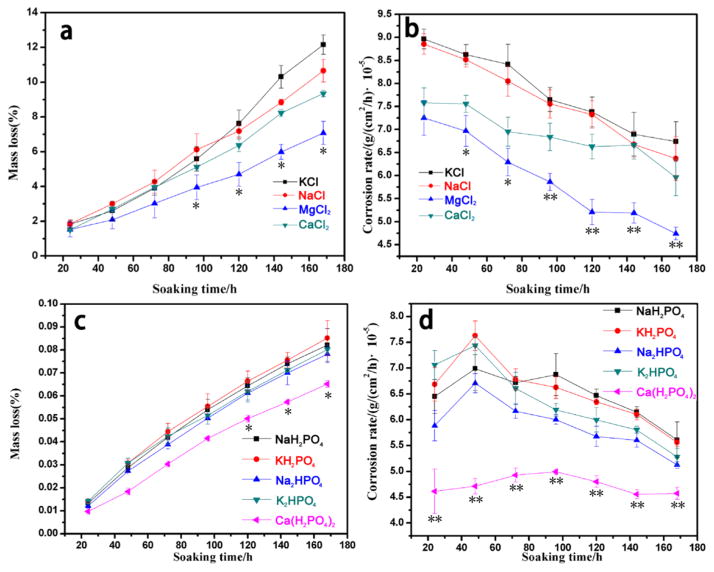

The mass loss and corrosion rate of AZ31B alloys during the immersion tests (n = 5) in each solution are shown in Figure 3. As indicated in Figure 3, the mass loss and corrosion rate during the degradation process were in agreement with the dynamic changes of pH values. Thus, the influence, reflected by the pH change and mass loss in the presence of the above metal cations, was decreased in the following order: K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+.

Figure 3.

Relationship between soaking time and average corrosion rate of AZ31B alloys at 37 °C: (a) mass loss of AZ31B alloys in solutions 1–4, (b) corrosion rate of AZ31B alloys in solutions 1–4, (c) mass loss of AZ31B alloys in solutions 5–9, and (d) corrosion rate of AZ31B alloys in solutions 5–9. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to all other groups.

3.2. Surface Morphology Observation

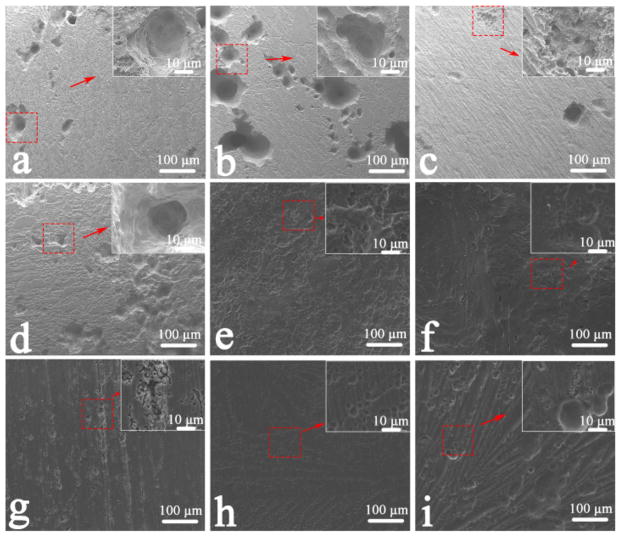

Figures 4 and 5 show the images of the surface of AZ31B alloys without and with corrosion products after immersion in the various solutions for 7 d. Localized corrosion occurred on the surface. The corrosion type could be identified as pitting corrosion, as shown in Figure 4. In solutions 7–9, where the degradation degree was smaller (Figure 4g–i), the scratch markings produced during grinding were the attractive sites for the initial corrosion, and nanosized Mg(OH)2 films formed in the matrix after immersion in solutions for 7 d, resulting in a rough surface. Corrosion pits appeared due to the galvanic corrosion between the anodic α-Mg matrix and the cathodic Al–Mn particles.27 As chloride ions greatly accelerated the degradation of Mg alloy,10 the morphologies of the surface corroded in the chlorine salt solution were insignificantly changed. Larger corrosion pits and filiform corrosion occurred in solutions 1–4 (Figure 4a–d). However, overall corrosion was initiated on the alloys as soon as the samples were soaked in solutions 5–9 (Figure 4e–i), as evidenced by the small scattered corrosion dots. Conspicuously, when different metal cations were present, the surface morphologies of corrosion product were different, even when the anions in the solutions were identical.

Figure 4.

SEM images of corroded surfaces of AZ31B alloys after immersion tests in different solutions for 7 d: (a) solution 1, (b) solution 2, (c) solution 3, (d) solution 4, (e) solution 5, (f) solution 6, (g) solution 7, (h) solution 8, and (i) solution 9.

Figure 5.

SEM images of corrosion products after immersion tests in different solutions for 7 days: (a) solution 1, (b) solution 2, (c) solution 3, (d) solution 4, (e) solution 5, (f) solution 6, (g) solution 7, (h) solution 8, and (i) solution 9.

Compared with samples soaked in solutions 1 and 5, those immersed in solutions 2 and 6 were corroded more severely. As shown in Figure 5, corrosion products had a similar microstructure in the presence of the same anions in the solutions. The scalelike Mg(OH)2 films could be observed in solutions 1–4 (Figure 5a–d), and honeycomb films with numerous microcracks spanning the whole surface appeared for solutions 5 and 6 (Figure 5e,f). As shown in Figure 5c, a thick and dense corrosion product was formed and composed of tiny styloid microstructures on the surface after the samples were immersed in solutions 7 and 8 (Figure 5g,h). However, the presence of metal cations influenced the macromorphologies of the corrosion products. The films in solutions 2 and 6 were loose compared with those in solutions 1 and 5. Simultaneously, a dense corrosion product was formed in solution 9, which might be affected by the Ca2+ in the solution. Figures 4 and 5 show the formation and morphologies of corrosion products influenced by metal cations. Hence, the corroded morphologies of Mg alloys were affected by the combination of corrosion products and metal cations themselves in the solutions.

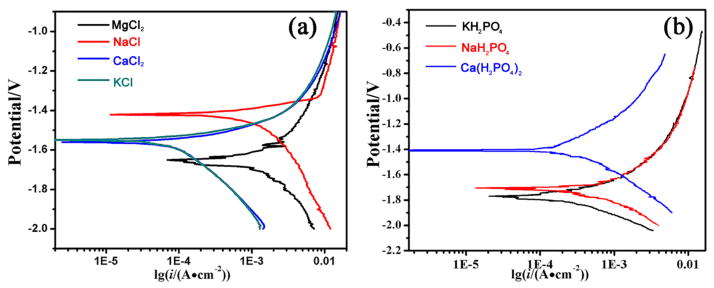

3.3. Electrochemical Test

The electrochemical polarization curves of AZ31B alloy samples in the presence of various cations are depicted in Figure 6. Although the anions were the same one, the corrosion potential (Ecorr) varied in the presence of different cations. It is obvious that the AZ31B alloys in solutions 1, 2, and 4 exhibit corrosion potentials (Ecorr) more positive than that in solution 3 in the presence of chloride ions (Figure 6a). This unexpected result may be explained by the fact that the chloride ions shifted the anodic polarization behavior and significantly decreased the corrosion resistance of the alloys. Howerver, in the presence of hydrogen phosphate and dihydrogen phosphate ions, the electrochemical polarization curves exhibited an Ecorr order of solution 9 (Ca2+) > solution 7 (Na+) > solution 8 (K+), which is consistent with the ranking of Mg alloy corrosion (Figure 6b). Accordingly, the corrosion current density of the alloy in the presence of chloride, hydrogen phosphate, and dihydrogen phosphate ions was lower than that in the presence of only chloride ions. This behavior was attributed to the prevention of cathodic hydrogen evolution due to the formation of phosphate precipitates. According to the corrosion current density, the influence of cations on the corrosion of AZ31 alloys declined in the following order: K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+.

Figure 6.

Electrochemical polarization curves of AZ31B alloys in solutions (a) 1–4 and (b) 7–9.

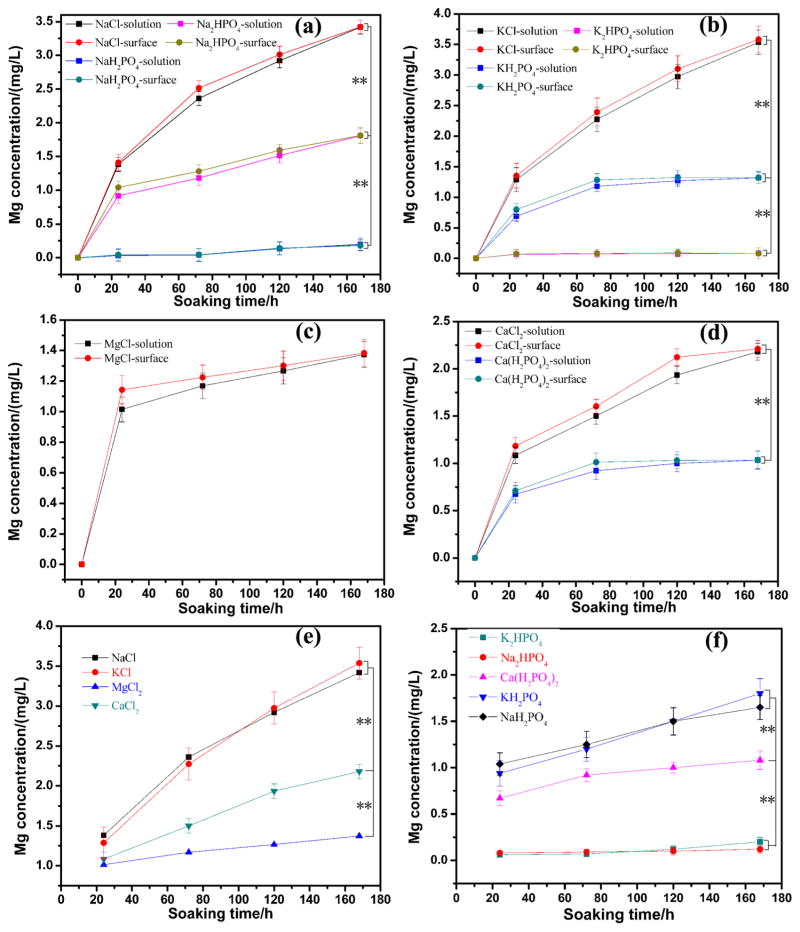

3.4. The Release of Mg2+ Analysis

Figure 7 shows the release of Mg2+ ions from both the sample surface and solutions. Accordingly, the concentration of Mg2+ ions in the solutions reflected the degradation degree of AZ31B alloys, and their surface concentration indicated the reaction rate. The concentration of Mg2+ ions increased both in the solution and on the surface (see Figure 7a–d) along with the increasing of soaking time. The concentration of Mg2+ ions on the surface was higher than that in solutions (Figure 7a–d). As shown in Figure 7e,f, when metal ions varied in different solutions, the reaction rate and the final concentration changed with the type of cations. The acceleration of the degradation process of AZ31B alloys by metal cations decreased as follows, regardless of the anions: K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+.

Figure 7.

Concentrations of Mg ions in different solutions and on different surfaces: (a) solutions 1, 5, 7; (b) solutions 2, 6, 8; (c) solution 3; (d) solutions 4, 9; (e) solutions 1–4; and (f) solutions 5–9. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 5, **p < 0.01).

Here we studied the effects of physiologically relevant cations individually at a concentration close to that of human blood and under stress condition on the corrosion behavior of Mg alloys. We assayed the variations in HERs, pH values, weight loss and the release of Mg2+, surface morphologies, and chemical components of corrosion products after immersion tests. The pH value increase in the solutions revealed that Mg hydroxide films formed on the AZ31B alloy (Figure 2). In solutions 1–4, the Mg(OH)2 dissolved by reacting with the chloride ions as follows:

| (6) |

As a result, corrosion pits and filiform corrosion were observed on the samples, as illustrated in Figure 4. The relationship between the concentration of Mg2+ ions ([Mg2+]) and pH value was proved to be28

| (7) |

For the solution saturated with Mg2+ ions, the concentration of Mg2+ ions is

| (8) |

Inserting eq 8 into eq 7 yields

| (9) |

Thus, 10.43 was designated as the pH value of the solution saturated with Mg2+ ions, which was consistent with the result shown in Figure 2. On the basis of reactions 1–3, the change in [Mg2+] with soaking time also reflects the corrosion rate for Mg and its alloys. The HER decreased continuously with increasing soaking time; however, the pH value did not always increase. This novel finding revealed the dissolution processes of the Mg(OH)2 precipitates.

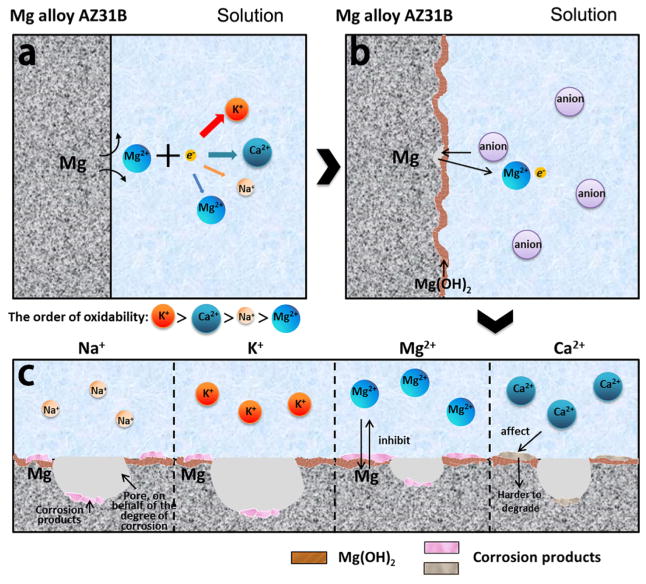

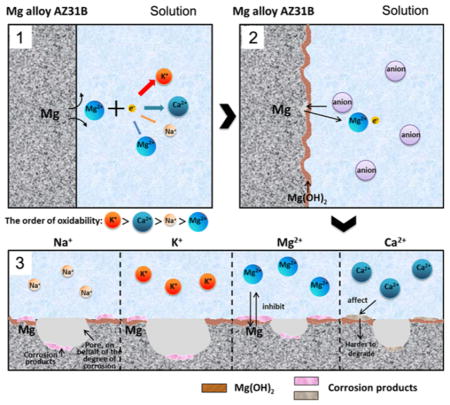

3.5. Mechanism of Metal Cations Influencing Degradation of Magnesium Alloys

The composition of the corrosion products was mainly Mg(OH)2 due to the anion composition in this experiment. There have been many studies on the structural and chemical properties as well as the mechanism of formation and decomposition of hydrotalcite and hydrotalcite-like compounds.29–31 It has been established that the hydrotalcite and hydrotalcite-like compounds improve the corrosion resistance of Mg alloys in aggressive environments.32,33 The corrosion rate of alloy AZ31B varied with different kinds of metal cations in both chlorine and hydrogen phosphate salt solutions. The corrosion products were similar when the anions in solution were chloride. Pardo et al.34 reported that the main corrosion product formed on the surface of some Mg–Al alloys in NaCl solution was brucite [Mg(OH)2]. During the degradation process, there was a drop after the samples were immersed in the solutions after 12 h, probably resulting from the chloride ions and galvanic reaction. This is because Mg(OH)2 can be converted into the more soluble MgCl2, although it is formed on the surface in NaCl solution.22 The similar reactions also occurred in other chlorine salt solutions, except for the influence of cations in solution. The corrosion products affected by the cations also had an effect on AZ31B alloys. However, corrosion potentials differed obviously in solutions 1–4, as shown in Figure 5. A possible mechanism of the effect of metal cations was related to the oxidizability of metal ions. Reaction 1 was respectively accelerated in solution 2, 6, and 8 compared with solutions 1, 5, and 7 due to the stronger oxidizability of potassium ion (Figures 2 and 6).

The small variations in the pH value increment in solutions containing HPO42− and H2PO4− may be attributed to several factors, including the consumption of OH− induced by dissolution of Mg when Mg3(PO4)2 was formed on the surface by chemical reaction with HPO42− and H2PO4− in solution, retardation of the dissolution of Mg due to the formation of stable, dense Mg3(PO4)2 on the surface, and the buffering effect of phosphate. The Mg/P atomic ratio in solutions 5, 6, 7, and 8 was 2.86, 1.75, 1.78, and 1.51, respectively, according to the EDS results in Table 2, which was higher than the expected Mg/P atomic ratio of 1.5 suggested by the formula Mg3(PO4)2. The presence of Mg(OH)2 as a corrosion product along with Mg3(PO4)2 would account for this observation.28 The many microcracks observed in the SEM images (Figure 4a–d) are probably produced due to dehydration of the corrosion products during the samples preparation process for SEM.6

Table 2.

Chemical Compositions of Corrosion Products Formed on the Surface after Immersion Tests in Solutions for 7 d Detected by EDS Analysis (atom %)

| solution | C | O | Na | K | Mg | P | Cl | Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (NaCl) | 5.82 | 63.12 | 0.49 | 30.51 | 0.06 | |||

| 2 (KCl) | 4.45 | 58.31 | 0.52 | 36.67 | 0.05 | |||

| 3 (MgCl2) | 1.42 | 59.12 | 39.34 | 0.12 | ||||

| 4 (CaCl2) | 2.31 | 57.38 | 20.59 | 0 | 0.07 | 19.65 | ||

| 5 (Na2HPO4) | 4.26 | 54.26 | 1.69 | 35.82 | 12.49 | |||

| 6 (K2HPO4) | 2.86 | 42.89 | 9.85 | 30.14 | 17.26 | |||

| 7 (NaH2PO4) | 1.23 | 62.48 | 1.34 | 22.39 | 12.56 | |||

| 8 (KH2PO4) | 2.72 | 46.15 | 1.03 | 30.73 | 20.37 | |||

| 9 [Ca(H2PO4)2] | 3.36 | 49.21 | 8.72 | 21.33 | 17.38 |

It is interesting to note the slow increase of the pH value in solution 9, which contains both calcium and dihydrogen phosphate ion (Figure 2). The pH value usually increases rapidly during immersion tests of AZ31B because H2 and OH− are generated at both the anode and cathode as Mg is corroded.22 The reason for the pH value decrease in solution 9 may be due to the formation of octacalcium phosphate (OCP) or the transformation of OCP into hydroxyapatite (HAp) on the surface of AZ31B alloys. These two processes increase the hydrogen ion concentration, as shown in the following chemical reactions (reactions 10–12),26,35 and result in the slow degradation rate of AZ31B alloys in the solutions containing calcium and dihydrogen phosphate ions:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

Figure 8 shows a possible schematic diagram of the effects of metal ions on the corrosion of AZ31B alloys. Immediately after contacting the solution, Mg is oxidized into Mg ions following the anodic reaction (reaction 1). The generated electrons are consumed by a cathodic reaction corresponding to the water reduction (reaction 2). Due to the difference in the extranuclear electron distribution and ionic size of the cations, the electron loss from the cations is affected by the oxidation ability of the cations in the order of K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+, which further promotes the corrosion of AZ31B alloys to a degree on the same order as reflected by reaction 1. According to reaction 3, Mg(OH)2 will be formed due to the corrosion. Furthermore, the existence of various metal cations results in the difference in the amount of the other formed corrosion products in the order of K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. In addition, in real-world application, the organic molecules, such as serum proteins, amino acids, and lipids, will adsorb over the metal surface, thereby influencing the degradation of Mg implants. In fact, many investigations reported that the degradation was delayed due to the adsorption of proteins on the metal surface.36–38 Thus, the barrier effect of the adsorbed protein layer is expected to matter in the degradation stage and weakens dramatically the degradation by reducing the action of metal cations in the physiological environment.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the corrosion at the magnesium interface. (a) Metal cations promote corrosion via reaction 1 in the order of oxidability shown. (b) The Mg(OH) layer formed by the mechanism of corrosion in reaction 3 covers the Mg alloy surface. (c) Metal cations promote the formation of the corrosion products with the degree being in the order of oxidability.

On the other hand, as the degradation proceeds, metal implants can release not only metal ions but also may be disintegrated into irregular particles falling into the surrounding media. Such phenomenon is often observed on Mg-based implants. Depending on the physicochemical properties of particles, a protein corona might form on the particle surface, which may further influence the degradation behavior.39,40 Meanwhile, this also significantly affects the interactions between the particles and the biological environment, including cellular components found within the blood system (endothelial cells, etc.).39–41 More detailed mechanisms remain to be studied.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, a pressure-bearing device, along with a solution made of cations found in blood, is employed to mimic the compressive corrosion environment after an Mg stent is implanted into the human body. By such a device, the effects of cations (K+, Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) found in blood plasma on the corrosion of the Mg alloys have been systematically studied using hydrogen evolution, mass loss determination, electron microscopy, pH value, and potentiodynamic measurements. The degree of the corrosion of the Mg alloys by metal cations is decreased in the order K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. We expect that these results are useful for future studies to understand the corrosion behavior of Mg alloys in vivo and will lead to better in vitro tests that can predict the in vivo behavior of magnesium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant no. 2012CB619100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51232002, 51372087, and 51072055), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2015A030313493), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2014A010105048). Y.Z. and C.B.M. are thankful for the financial support from National Institutes of Health (CA200504 and CA195607), National Science Foundation (CMMI-1234957 and CBET-1512664), Department of Defense Office of the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (W81XWH-15-1-0180), Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research (434003), and Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR14-160).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.lang-muir.5b03699.

- Schematic diagram of the immersion test setup with pressure added and aqueous solutions of different cations and SEM image of the surface of control AZ31B alloy without any treatment (PDF)

Contributor Information

Chengyun Ning, Email: imcyning@scut.edu.cn.

Yingjun Wang, Email: imwangyj@163.com.

Chuanbin Mao, Email: cbmao@ou.edu.

References

- 1.Witte F, Kaese V, Haferkamp H, Switzer E, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Wirth C, Windhagen H. In Vivo Corrosion of Four Magnesium Alloys and the Associated Bone Response. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3557–3563. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zartner P, Cesnjevar R, Singer H, Weyand M. First Successful Implantation of A Biodegradable Metal Stent into the Left Pulmonary Artery of a Preterm Baby. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:590–594. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krause A, Von der Höh N, Bormann D, Krause C, Bach FW, Windhagen H, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Degradation Behaviour and Mechanical Properties of Magnesium Implants in Rabbit Tibiae. J Mater Sci. 2010;45:624–632. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Shinohara T, Zhang BP. Influence of Chloride, Sulfate and Bicarbonate Anions on the Corrosion Behavior of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. J Alloys Compd. 2010;496:500–507. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu X, Zheng Y, Chen L. Influence of Artificial Biological Fluid Composition on the Biocorrosion of Potential Orthopedic Mg–Ca, AZ31, AZ91 Alloys. Biomed Mater. 2009;4:065011. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/6/065011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xin Y, Huo K, Tao H, Tang G, Chu PK. Influence of Aggressive Ions on the Degradation Behavior of Biomedical Magnesium Alloy in Physiological Environment. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:2008–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waizy H, Weizbauer A, Modrejewski C, Witte F, Windhagen H, Lucas A, Kieke M, Denkena B, Behrens P, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Bach FW, Thorey F. In Vitro Corrosion of ZEK100 Plates in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution. Biomed Eng Online. 2012;11:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zainal Abidin NI, Martin D, Atrens A. Corrosion of High Purity Mg, AZ91, ZE41 and Mg2Zn0. 2Mn in Hank’s Solution at Room Temperature. Corros Sci. 2011;53:862–872. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xin Y, Liu C, Zhang X, Tang G, Tian X, Chu PK. Corrosion Behavior of Biomedical AZ91 Magnesium Alloy in Simulated Body Fluids. J Mater Res. 2007;22:2004–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rettig R, Virtanen S. Composition of Corrosion Layers on A Magnesium Rare-Earth Alloy in Simulated Body Fluids. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2009;88A:359–369. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carboneras M, García-Alonso M, Escudero M. Biodegradation Kinetics of Modified Magnesium-Based Materials in Cell Culture Medium. Corros Sci. 2011;53:1433–1439. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willumeit R, Fischer J, Feyerabend F, Hort N, Bismayer U, Heidrich S, Mihailova B. Chemical Surface Alteration of Biodegradable Magnesium Exposed to Corrosion Media. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2704–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulbrandsen E. Anodic behaviour of Mg in HCO3−/CO32− Buffer Solutions. Quasi-Steady Measurements. Electrochim Acta. 1992;37:1403–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto A, Hiromoto S. Effect of Inorganic Salts, Amino Acids and Proteins on the Degradation of Pure Magnesium in Vitro. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2009;29:1559–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Taib Heakal F, Mohammed Fekry A, Ziad Fatayerji M. Electrochemical Behavior of AZ91D Magnesium Alloy in Phosphate Medium—Part I. Effect of pH. J Appl Electrochem. 2009;39:583–591. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukaski HC. Methods for the Assessment of Human Body Composition: Traditional and New. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:537–556. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prosek T, Thierry D, Taxén C, Maixner J. Effect of Cations on Corrosion of Zinc and Carbon Steel Covered with Chloride Deposits Under Atmospheric Conditions. Corros Sci. 2007;49:2676–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin MA, Abd El Rehim SS, El-Naggar M, Abdel-Fatah HT. Assessment of EFM as a New Nondestructive Technique for Monitoring the Corrosion Inhibition of Low Chromium Alloy Steel in 0.5 M HCl by Tyrosine. J Mater Sci. 2009;44:6258–6272. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poursaee A, Laurent A, Hansson C. Corrosion of Steel Bars in OPC Mortar Exposed to NaCl, MgCl2 and CaCl2: Macro-and Micro-cell Corrosion Perspective. Cem Concr Res. 2010;40:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JT, Leng Y, Chow KL, Ren F, Ge X, Wang K, Lu X. Cell Culture Medium as an Alternative to Conventional Simulated Body Fluid. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2615–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu X, Zhou W, Zheng Y, Cheng Y, Wei S, Zhong S, Xi T, Chen L. Corrosion Fatigue Behaviors of Two Biomedical Mg Alloys–AZ91D and WE43–in Simulated Body Fluid. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4605–4613. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song G, Atrens A. Understanding Magnesium Corrosion. Adv Eng Mater. 2003;5:837–858. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng RC, Sun L, Zheng YF, Cui HZ, Han EH. Corrosion and Characterisation of Dual Phase Mg–Li–Ca Alloy in Hank’s solution: the influence of Microstructural Features. Corros Sci. 2014;79:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y, Shan D, Chen R, Zhang F, Han EH. Biodegradable Behaviors of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2009;29:1039–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y, Liu W, Wen C, Pan H, Wang T, Darvell BW, Lu WW, Huang W. Bone Regeneration: Importance of Local pH—Strontium-Doped Borosilicate Scaffold. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:8662–8670. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong HM, Yeung KW, Lam KO, Tam V, Chu PK, Luk KD, Cheung KM. A Biodegradable Polymer-Based Coating to Control the Performance of Magnesium Alloy Orthopaedic Implants. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2084–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng RC, Zhou W, Han E, Ke W. Effect of pH Value on Corrosion as-Extruded AM60 Magnesium Alloy. Acta Metall Sin. 2005;44:307–311. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su Y, Li G, Lian J. A Chemical Conversion Hydroxyapatite Coating on AZ60 Magnesium Alloy and its Electrochemical Corrosion Behaviour. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2012;7:11497–11511. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyata S. Anion-Exchange Properties of Hydrotalcite-Like Compounds. Clays Clay Miner. 1983;31:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trave A, Selloni A, Goursot A, Tichit D, Weber J. First Principles Study of the Structure and Chemistry of Mg-Based Hydrotalcite-Like Anionic Clays. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:12291–12296. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellotto M, Rebours B, Clause O, Lynch J, Bazin D, Elkaïm E. A Reexamination of Hydrotalcite Crystal Chemistry. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:8527–8534. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Song Y, Shan D, Han EH. Study of the Corrosion Mechanism of the in situ Grown Mg–Al–CO32− Hydrotalcite Film on AZ31 Alloy. Corros Sci. 2012;65:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Song Y, Shan D, Han EH. In situ Growth of Mg–Al Hydrotalcite Conversion Film on AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Corros Sci. 2011;53:3281–3288. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pardo A, Merino M, Coy A, Viejo F, Arrabal R, Feliu S. Influence of Microstructure and Composition on the Corrosion Behaviour of Mg/Al Alloys in Chloride Media. Electrochim Acta. 2008;53:7890–7902. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrere F, Layrolle P, Van Blitterswijk C, De Groot K. Biomimetic Calcium Phosphate Coatings on Ti6Al4V: A Crystal Growth Study of Octacalcium Phosphate and Inhibition by Mg2+ and HCO3−. Bone. 1999;25:107S–111S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willumeit R, Fischer J, Feyerabend F, Hort N, Bismayer U, Heidrich S, Mihailova B. Chemical Surface Alteration of Biodegradable Magnesium Exposed to Corrosion Media. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2704–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Kong N, Shi Y, Niu J, Mao L, Li H, Xiong M, Yuan G. Influence of Proteins and Cells on in vitro Corrosion of Mg–Nd–Zn–Zr alloy. Corros Sci. 2014;85:477–481. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Lim CS, Lim CV, Yong MS, Teo EK, Moh LN. In vitro Degradation Behavior of M1A Magnesium Alloy in Protein-Containing Simulated Body Fluid. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2011;31:579–587. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Setyawati MI, Tay CY, Docter D, Stauber RH, Leong DT. Understanding and Exploiting Nanoparticles’ Intimacy with the Blood Vessel and Blood. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:8174–8199. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00499c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tay CY, Setyawati MI, Xie J, Parak WJ, Leong DT. Back to Basics: Exploiting the Innate Physico-chemical Characteristics of Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:5936–5955. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Setyawati MI, Tay CY, Chia SL, Goh SL, Fang W, Neo MJ, Chong HC, Tan SM, Loo SC, Ng KW, Xie JP, Ong CN, Tan NS, Leong DT. Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials Cause Endothelial Cell Leakiness by Disrupting the Homophilic Interaction of VE-cadherin. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1673. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.