Abstract

Objective

Prior research indicates a connection between the experience of trauma and use of intimate partner aggression (IPA), but little work has focused on core cognitive schemas that can be influenced by trauma. In the current study, we examine the cognitive schema of mistrust in others as a mediator of the relationship between trauma exposure and IPA use. This schema may lead to IPA through distorted social information processing that can escalate relationship conflict.

Method

The sample consisted of 83 heterosexual community couples. All variables were assessed via written questionnaires, and IPA frequency was calculated by incorporating both partners’ reports on each member of the couple.

Results

For males, mistrust significantly mediated the relationships between trauma exposure and both physical and psychological IPA use. For females, mistrust did not mediate the significant relationship between trauma exposure and IPA use. In analyses using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model, both actor and partner mistrust uniquely predicted physical and psychological IPA use.

Conclusions

Findings of the study suggest the importance of examining core schemas that may underlie trauma reactions and use of IPA.

Keywords: partner violence, abuse, trauma, mistrust, aggression, schema

A large research base indicates that exposure to traumatic events represents an important risk factor for the use of aggression in intimate relationships (e.g., Delsol & Margolin, 2004; Maguire et al., 2015). However, little work to date has been devoted to understanding how core cognitive schemas (i.e., enduring cognitions about oneself, others, and the world) may explain the link between trauma and intimate partner aggression (IPA)1 use. Models for trauma-related disorders and problems highlight the role of underlying schemas or core beliefs that are altered due to trauma exposure (Resick & Schnicke, 1993). It has been suggested that these schemas that are impacted by trauma may also underlie relationship problems and aggressive behavior (Taft, Walling, Howard, & Monson, 2011). In this study we explicitly examine one core schema, mistrust of others, as a possible mediator variable that accounts for the association between trauma exposure and IPA in a sample of community couples.

Traumatic experiences can deeply disrupt one’s trust in others, as the trauma may have been caused by the negligent or purposeful actions of others that were supposed to be trustworthy (e.g., parents or relationship partners), and this reduced trust may serve as a self-preservation mechanism in order to avoid vulnerability to future trauma (Taft, Murphy, & Creech, 2016). In a study among undergraduate students, Gobin and Freyd (2014) found that experiences of trauma involving betrayal were associated with lower levels of self-reported general and relationship-specific trust. Prior research also indicates the particular importance of mistrust to aggressive behavior. Tremblay and Dozois (2009) found that, when examined alongside 14 other cognitive schemas, mistrust was the only schema to show significant unique prediction of all aggression variables? Mistrust of others’ intentions may lead to engaging in IPA through distorted social information processing that can then escalate relationship conflict (Taft et al., 2011). For example, one partner may attribute negative intent to a benign comment and react with defensiveness or hostility in response, increasing the conflict.

In this study we investigated the relationships between trauma, mistrust, and IPA use. We hypothesized that mistrust would significantly mediate the association between trauma exposure and IPA use for both males and females. Additionally, because both members of a couple may influence one another, we examined the relationship between mistrust and IPA use with the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006). We hypothesized that both one’s own mistrust and one’s partner’s mistrust would uniquely predict one’s own IPA use.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 83 male-female couples (166 individuals) recruited from the greater Boston area. Participants were recruited via the following sources: (a) flyers posted in the Boston area, (b) newspaper advertisements in various local papers and classifieds, (c) online postings for volunteers via Craigslist, and (d) online postings on job boards at a local university. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: (1) participants were between the ages of 18 and 60; (2) participants were involved in a heterosexual relationship and either married or cohabitating for a period of at least 6 months; (3) participants had not been in inpatient treatment for drug or alcohol problems or begun methadone maintenance in the previous 2 months; (4) female participants were not pregnant or currently trying to become pregnant; and (5) participants were able to read and speak English. Participants completed all measures in-person at the study site, and members of the couple were separated during assessment to reduce one’s influence over one’s partner’s responses. The measures of trauma exposure and IPA use were administered in an initial session, and the measure of mistrust was administered in a second session approximately one week later. In both sessions, participants also completed assessments and procedures beyond the scope of the present study. Participants received $40 for completing the initial session, $60 for completing the second session, and a $20 bonus for completing both of the initial sessions ($120 total).

The average age was 37.37 years (SD = 12.15) for males and 35.35 years (SD = 11.71) for females. The average length of relationship was 6.47 years (SD = 7.50). With regard to relationship status, 33.7% of the couples were married, 65.1% were unmarried and cohabitating, and 1.2% were married and separated (this couple reported daily contact within the prior 6 months). The median previous year income was $10,001–$15,000 for males and $5,001–$10,000 for females. With respect to racial/ethnic demographics, 47.0% of the males and 51.8% of the females identified as Non-Hispanic Caucasian, 31.3% of the males and 24.1% of the females identified as Black or African American, 13.3% of the males and 10.8% of the females identified as Hispanic or Latino, 4.8% of the males and 7.2% of the females identified as Asian, 1.2% of the males and females identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 2.4% of the males and 4.8% of the females identified as another race or ethnicity.

Measures

The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000) was used to assess lifetime exposure to 16 different types of potentially traumatic events (PTEs), including motor vehicle accident, natural disaster, combat/warfare, and robbery with a weapon. For each PTE, participants endorsed a frequency of occurrence, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 5 times). The frequency scores for each item were summed to create a total score representing the estimated frequency of lifetime exposure to PTEs. Due to potential overlap with the outcome variable, IPA victimization was omitted from this total score. With the exception of two male participants, all participants endorsed exposure to at least one PTE. Prior research supports the content validity, convergent validity, and test-retest reliability of the measure (Kubany et al., 2000).

The 5-item Mistrust/Abuse subscale of the Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form (YSQ-SF; Young, 1998) was used to assess the schema of mistrust in others. Respondents indicate their level of agreement with each item on a scale of 1 (Completely untrue of me) to 6 (Describes me perfectly). A sample item of this subscale is “I feel that people will take advantage of me.” In this sample, α = .83 for males and α = .95 for females.

The 12-item Physical Assault and 8-item Psychological Aggression subscales of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) were utilized to assess IPA use. This is the most commonly used measure of IPA and has demonstrated sound psychometric properties (Straus et al., 1996). Example items for the Physical Assault scale include “I pushed or shoved my partner” and “I slammed my partner against a wall.” Example items for the Psychological Aggression scale include “I insulted or swore at my partner” and “I destroyed something belonging to my partner.” Participants indicated the frequency with which they and their partners had engaged in each behavior over the previous 6 months. We sought to mitigate the risk of IPA underreporting by integrating reports from both members of the couple. Specifically, we compared both partners’ responses on each item and took the higher of the two responses before summing the items to create each subscale. Variety scores (i.e., dichotomous endorsement of each item) were used for the Physical Assault subscale and frequency scores were used for the Psychological Aggression subscale. For the assessment of physical IPA, using variety scores is preferable because it reduces skewness created by a small number of participants with high frequencies of physical IPA, gives equal weight to each behavior, and is less affected by memory limitations regarding the frequency of each behavior. Using frequency scores for psychological IPA is more appropriate due to the greater overall incidence of each variety of psychological IPA in the sample. IPA variables were square-root transformed to reduce skewness.

We also examined the level of agreement between partner reports. Percentage of occurrence agreement (i.e., the number of couples that agreed that IPA had occurred, divided by the number of couples in which at least one member reported its occurrence) was 52.4% for males’ physical IPA, 53.8% for females’ physical IPA, 82.7% for males’ psychological IPA, and 88.9% for females’ psychological IPA. Pearson correlations indicated that male and female reports were significantly correlated for males’ physical IPA (r = .43, p < .001), females’ physical IPA (r = .44, p < .001), males’ psychological IPA (r = .43, p < .001), and females’ psychological IPA (r = .46, p < .001), all showing medium effect sizes.

Data Analysis

We first conducted descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all study variables. Effect size interpretation for correlations followed Cohen’s (1988) guidelines for small (.1 ≤ r < .3), medium (.3 ≤ r < .5), and large (r ≥ .5) effects. Next, we ran mediation models with PTE exposure as the independent variable, mistrust as the mediating variable, and IPA use as the outcome variable. A total of 4 mediation models were run, with the following outcome variables: males’ physical IPA, males’ psychological IPA, females’ physical IPA, and females’ psychological IPA. We employed bootstrap analysis of the sampling distribution to test the significance of indirect effects. This approach is preferable to the causal steps approach by Baron and Kenny (1986), which does not directly test the significance of indirect effects, and is also preferable to the Sobel test, which may incorrectly assume normality of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect (Hayes, 2009). As the transformed IPA variables do not facilitate intuitive interpretation, all variables were standardized prior to running the analyses. We provided PM as an index of effect size of the mediated effect. This index represents the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect, and is recommended by Wen and Fan (2015) in cases when the indirect and direct effects are in the same direction.

Finally, we examined the relationship between mistrust and IPA use with the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) using multilevel modeling techniques in SPSS 21.0 (Kenny et al., 2006). Both actor and partner effects were modeled. An actor effect is the effect of an individual’s own predictor on his or her own outcome, and a partner effect is the effect of an individual’s partner’s predictor on the individual’s outcome. In the current study, the effect of one’s mistrust on one’s own use of IPA represents an actor effect, and the effect of one’s partner’s mistrust on one’s own use of IPA represents a partner effect. APIM for distinguishable dyads was used because heterosexual couples are distinguishable by gender. Two APIMs were estimated, with one for physical IPA and one for psychological IPA. We examined interactions between gender and actor mistrust using techniques described by Kenny and colleagues (2006).

All analyses were additionally rerun with self-reported IPA use (in contrast to couples’ combined reports of IPA). These results are not presented in full, but any differences in statistical significance between these and the primary analyses are noted in tables, and they are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the variables of interest are presented in Table 1. For both males and females, PTE exposure, mistrust, and IPA use were all significantly and positively correlated with one another. Correlations between mistrust and IPA use were in the medium range of magnitude for males, and were in the small to medium ranges of magnitude for females. Additionally, there were several significant cross-partner associations.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

| Variable | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Male PTE Exposure | 15.89 | 12.86 | -- | ||||||

| 2. Male Mistrust | 12.34 | 5.67 | .43*** | -- | |||||

| 3. Male Physical IPA Use | 1.01 | 0.89 | .25* | .40*** | -- | ||||

| 4. Male Psychological IPA Use | 5.69 | 3.16 | .25* | .41*** | .48*** | -- | |||

| 5. Female PTE Exposure | 19.82 | 18.28 | .43*** | .44*** | .39*** | .37** | -- | ||

| 6. Female Mistrust | 13.32 | 7.53 | .23* | .24* | .30**a. | .39*** | .59*** | -- | |

| 7. Female Physical IPA Use | 1.18 | 0.87 | .14 | .32** | .82*** | .42*** | .34** | .22*a. | -- |

| 8. Female Psychological IPA Use | 5.56 | 3.01 | .18 | .42*** | .54*** | .87*** | .36** | .35** | .54*** |

Note. All IPA variables are from combined reports from both members of the couple. Any differences in statistical significance with self-reported IPA use are noted in the table. Square-root transformed variety scores were used for physical IPA, and square-root transformed frequency scores were used for psychological IPA.

Abbreviations: PTE, Potentially Traumatic Event; IPA, Intimate Partner Aggression.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Not significant with self-reported IPA use

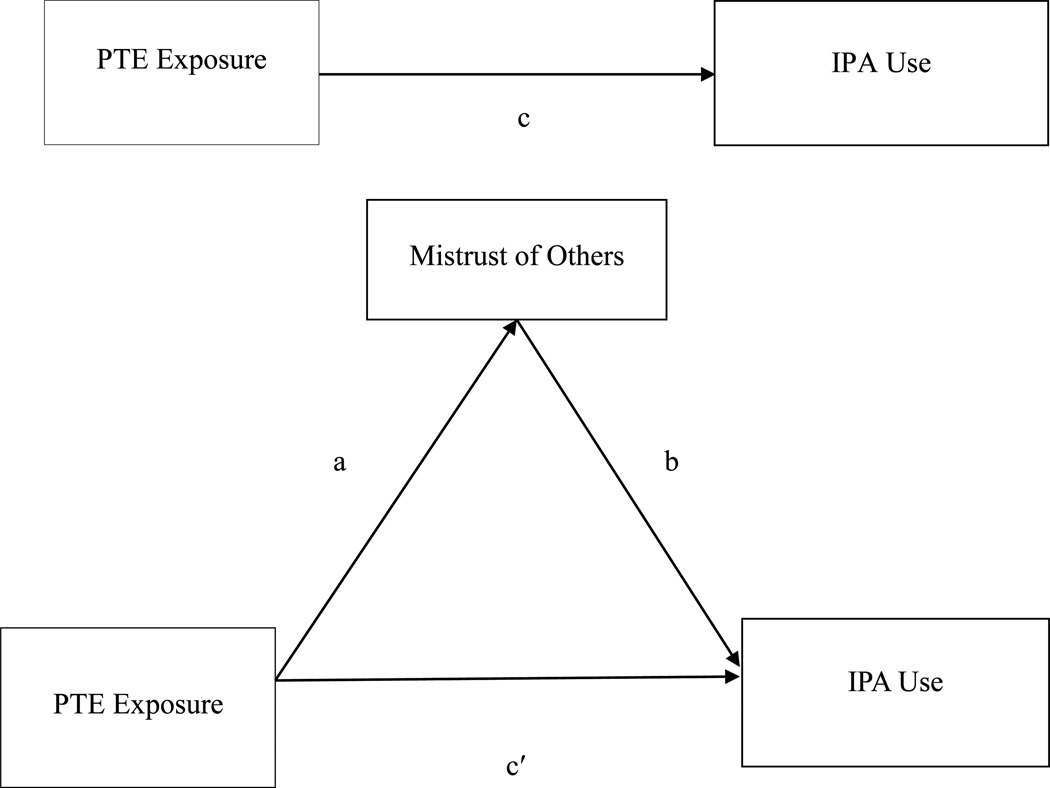

Results of mediation analyses are presented in Table 2, and the general mediation model is presented in Figure 1 to facilitate interpretation. In support of hypotheses, mistrust significantly mediated the relationships between males’ PTE exposure and their physical and psychological IPA use. In both cases, the effect of PTE exposure on IPA use was no longer significant after controlling for mistrust. Additionally, the indirect effect through mistrust represented 61% of PTE exposure’s total effect on males’ physical IPA use, and 63% of PTE exposure’s total effect on males’ psychological IPA use. In contrast, for females, mistrust did not significantly mediate the relationship between PTE exposure and physical or psychological IPA use. Interestingly, the total effect of PTE exposure on physical and psychological IPA use was somewhat higher for the females in the sample than for the males, and the direct effect remained significant for females’ physical IPA use. Additionally, the relationship between PTE exposure and mistrust appeared even stronger for females than for males, but the relationship between mistrust and IPA use was weaker for females, particularly for physical IPA. Together this suggests that, for females, PTE exposure is as strongly related to IPA use as for males, but mistrust does not explain this relationship.

Table 2.

Results of Mediation Analyses

| Dependent Variable | R2 | c path (SE) | a path (SE) | b path (SE) | c′ path (SE) | a × b (SE) | 95% CI of a × b | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | ||||||||

| Physical IPA | .17*** | 0.25 (0.11)* | 0.43 (0.10)*** | 0.36 (0.11)** | 0.10 (0.11)a. | 0.15 (0.06)* | 0.07 to 0.29 | .61 |

| Psychological IPA | .17*** | 0.25 (0.11)* | 0.43 (0.10)*** | 0.37 (0.11)** | 0.09 (0.11)a. | 0.16 (0.05)* | 0.07 to 0.28 | .63 |

| Female | ||||||||

| Physical IPA | .11** | 0.34 (0.10)** | 0.59 (0.09)*** | 0.04 (0.13) | 0.32 (0.13)* | 0.02 (0.08) | −0.13 to 0.20 | .07 |

| Psychological IPA | .16** | 0.36 (0.10)*** | 0.59 (0.09)*** | 0.21 (0.13)a. | 0.24 (0.13) | 0.12 (0.11) | −0.06 to 0.36 | .34 |

Note. 95% bias-corrected CIs were calculated on the basis of 5,000 bootstrap samples. All IPA variables are from combined reports from both members of the couple. Any differences in statistical significance with self-reported IPA use are noted in the table. Square-root transformed variety scores were used for physical IPA, and square-root transformed frequency scores were used for psychological IPA. All analyses are based on standardized variables.

Abbreviations: IPA, Intimate Partner Aggression; CI, Confidence Interval.

p <.05 or CIs that did not cross zero.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Significant with self-reported IPA use

Figure 1.

Mistrust of others as a mediator of the relationship between PTE exposure and IPA use. The c path represents PTE exposure’s prediction of IPA use, the a path represents PTE exposure’s prediction of mistrust, the b path represents mistrust’s prediction of IPA use controlling for PTE exposure, the c′ path represents PTE exposure’s prediction of IPA use controlling for mistrust, and a×b represents the indirect effect of PTE exposure on IPA use through mistrust.

Abbreviations: PTE, Potentially Traumatic Event; IPA, Intimate Partner Aggression.

Results of APIM analyses are presented in Table 3. Interactions between gender and actor mistrust were not significant in predicting either physical or psychological IPA, and so they were removed from the final model. Consistent with hypotheses, both actor and partner mistrust uniquely predicted greater physical and psychological IPA use.

Table 3.

Multilevel Model Analyses with Mistrust Predicting Use of Physical and Psychological IPA

| Final Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical IPA Use | β | SE | t |

| Constant | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.98 |

| Gender | −0.20 | 0.07 | −3.04** |

| A Mistrust | 0.24 | 0.07 | 3.61*** |

| P Mistrust | 0.25 | 0.07 | 3.75*** |

| Psychological IPA Use | β | SE | t |

| Constant | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.20 |

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.67a. |

| A Mistrust | 0.29 | 0.06 | 4.61*** |

| P Mistrust | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.21*** |

Note. All IPA variables are from combined reports from both members of the couple. Any differences in statistical significance with self-reported IPA use are noted in the table. Square-root transformed variety scores were used for physical IPA, and square-root transformed frequency scores were used for psychological IPA. All analyses are based on standardized variables, with the exception of Gender, which was coded as 0 = female, 1 = male.

Abbreviations: IPA, Intimate Partner Aggression; A, Actor Effect; P, Partner Effect.

p <.01.

p <.001.

Significant with self-reported IPA use in negative direction

Discussion

Mediation results indicate that, for males, the cognitive schema of mistrust represents an important link between lifetime exposure to PTEs and both physical and psychological IPA use. Additionally, APIM results indicated that, regardless of gender, both one’s own and one’s partner’s mistrust uniquely predict physical and psychological IPA use. These findings are consistent with some of the clinical literature on people who engage in IPA (Taft et al., 2016), and are also aligned with research on social information processing deficits that can result from trauma and contribute to IPA use (Taft, Schumm, Marshall, Panuzio, & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2008). People who constantly look for evidence of hostility and betrayal in others due to past trauma experiences may then escalate conflict and/or attempt to control their partners through abusive behaviors (Taft et al., 2016).

For females, it is notable that mistrust did not mediate the relationship between PTE exposure and IPA use. As females’ mistrust was significantly associated with their physical and psychological IPA use in bivariate analyses and APIM results did not show significant gender interactions, it is possible that our modest sample size may not have provided sufficient power to detect a mediation effect. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a true gender difference in the association between mistrust and IPA use. A meta-analysis found that the association between PTSD symptoms and IPA use was stronger for men than for women, but the association between PTSD symptoms and relationship discord did not show a gender difference, consistent with the idea that women tend to experience and express more internalizing posttraumatic pathology, whereas men may exhibit more externalizing posttraumatic pathology (Taft, Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, 2011). However, in the current sample, the lack of gender differences in overall IPA use and the somewhat larger associations found between PTE exposure and IPA use for females suggest that other factors may explain this relationship, potentially including other cognitive schemas. For example, past research has found that female trauma survivors tend to endorse greater self-blame for the event, greater beliefs that they are damaged or incompetent, and greater beliefs that the world is dangerous, as compared to male trauma survivors (Tolin & Foa, 2002). Additionally, implicit shame-processing bias has been shown to explain the relationship between PTSD symptoms and IPA use, based on the idea that aggression toward the source of expected negative evaluation and rejection may be used to minimize the discomfort produced by these expectations (Sippel & Marshall, 2011). Thus, it may be beneficial for future work to examine other cognitive schemas (e.g., self-esteem, power and control) as mediators of the relationship between trauma and IPA use for both men and women.

Limitations should be noted, such as our modest sample size and inclusion of only heterosexual couples. The relatively low-income and racially/ethnically diverse nature of the sample should be considered, given that people lower in socioeconomic status and people in racial/ethnic minority groups tend to experience more frequent trauma (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007), and may have greater mistrust of others due to experiences of racism and/or classism. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to rule out alternative causal explanations. Our use of combined reports for IPA variables was designed to mitigate risk of underreporting, but this scoring procedure likely increases risk of IPA overreporting. However, analyses using only self-reports of IPA use did not substantially change interpretation of the findings. Notably, all variables together accounted for less than 20% of the variance in the IPA variables, signifying that a multitude of factors contribute to the use of aggression in relationships. One potential reason that mistrust did not show a larger association is that we examined general mistrust of others, rather than relationship-specific mistrust. Another important limitation endemic to this area of research is that the assessment of IPA did not include information about whether a particular partner initiated the aggressive acts or used them in self-defense, which precludes a better understanding of these dynamics.

Mistrust in this study was assessed using a single 5-item self-report measure. Because it is easy to administer, this subscale of the YSQ-SF could have beneficial clinical applications in abuser intervention programs, pending successful replication of these findings among clinical samples of abusers. Discussing the role of trauma in forming one’s views of others may provide valuable insight for those trying to end their abusive behavior, and the current study suggests that, particularly for men, the mistrust of others represents an important schema to consider.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by National Institute of Mental Health Award K08 MH73117 01A2 to Casey T. Taft.

Footnotes

The terms “intimate partner aggression,” “intimate partner violence,” and “marital conflict” are often used interchangeably. We used the term “intimate partner aggression” instead of “intimate partner violence” in this study because we felt it would be more appropriate given our examination of psychological aggression alongside physical violence. Additionally, the term “marital conflict” was not used because not all couples in the sample are married.

Contributor Information

Adam D. LaMotte, Behavioral Science Division, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System

Casey T. Taft, Behavioral Science Division, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine

Robin P. Weatherill, Behavioral Science Division, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Department of Psychiatry, Boston University School of Medicine

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Delsol C, Margolin G. The role of family-of-origin violence in men's marital violence perpetration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:99–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. The impact of betrayal trauma on the tendency to trust. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: A review of the research. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40:313–332. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Leisen MB, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Haynes SN, Owens JA, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire E, Macdonald A, Krill S, Holowka DW, Marx BP, Woodward H, Taft CT. Examining trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in court-mandated intimate partner violence perpetrators. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2015 doi: 10.1037/a0039253. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment manual. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Marshall AD. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence perpetration, and the mediating role of shame processing bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Murphy CM, Creech SK. Trauma-informed treatment and prevention of intimate partner violence. Washington DC: US: American Psychological Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm JA, Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Family-of-origin maltreatment, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, social information processing deficits, and relationship abuse perpetration. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:637–646. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Walling SM, Howard JM, Monson CM. Trauma, PTSD and partner violence in military families. In: MacDermid Wadsworth S, Riggs D, editors. U.S. Military Families Under Stress. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Watkins LE, Stafford J, Street AE, Monson CM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Foa EB. Gender and PTSD: A cognitive model. In: Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Wolfe J, Kimerling R, Ouimette P, Wolfe J, editors. Gender and PTSD. New York, NY: US: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay PF, Dozois DA. Another perspective on trait aggressiveness: Overlap with early maladaptive schemas. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Fan X. Monotonicity of effect sizes: Questioning kappa-squared as mediation effect size measure. Psychological Methods. 2015;20(2):193–203. doi: 10.1037/met0000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JE. Young schema questionnaire short form. New York: Cognitive Therapy Center; 1998. [Google Scholar]