Abstract

Local (skeletal muscle and adipose) and systemic inflammation are implicated in the development of obesity-associated insulin resistance in humans. In horses, obesity is neither strongly nor consistently associated with systemic inflammation. The role of skeletal muscle inflammation in the development of insulin dysregulation (insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia) remains to be determined. We hypothesized that skeletal muscle inflammation is related to obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia in horses. Thirty-five light-breed horses with body condition scores (BCSs) of 3/9 to 9/9 were studied, including 7 obese, normoinsulinemic (BCS ≥ 7, resting serum insulin < 30 μIU/mL) and 6 obese, hyperinsulinemic (resting serum insulin ≥ 30 μIU/mL) horses. Inflammatory biomarkers were evaluated in skeletal muscle biopsies and plasma. Relationships between markers of inflammation and BCS were evaluated. To assess the role of inflammation in obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia, markers of inflammation were compared among lean or ideal, normoinsulinemic (L-NI); obese, normoinsulinemic (O-NI); and obese, hyperinsulinemic (O-HI) horses. Skeletal muscle and plasma tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) concentrations were negatively correlated with BCS. When comparing inflammatory markers among groups, skeletal muscle TNFα was lower in the O-HI group than in the O-NI or L-NI groups. In horses, neither skeletal muscle nor systemic inflammation appears to be positively related to obesity or obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia.

Résumé

L’inflammation locale (muscle squelettique et tissu adipeux) et systémique sont impliquées dans le développement de la résistance à l’insuline associée à l’obésité chez l’humain. Chez les chevaux, l’obésité n’est pas fortement ou de manière constante associée avec l’inflammation systémique. Le rôle de l’inflammation des muscles squelettiques dans le développement de la dérégulation de l’insuline (résistance à l’insuline ou hyper-insulinémie) reste à être déterminé. Nous avons émis l’hypothèse que chez les chevaux l’inflammation des muscles squelettiques est reliée à l’hyper-insulinémie associée à l’obésité. Trente-cinq chevaux de race légère avec des pointages de condition corporelle (PCCs) variant de 3/9 à 9/9 ont été étudiés, incluant sept chevaux obèses, normo-insulinémique (PCC ≥ 7, insuline sérique au repos < 30 μUI/mL) et six chevaux obèses, hyper-insulinémique (insuline sérique au repos ≥ 30 μUI/mL). Les biomarqueurs de l’inflammation ont été évalués dans des biopsies de muscles squelettiques et le plasma. Les relations entre les marqueurs de l’inflammation et le PCC ont été évaluées. Pour apprécier le rôle de l’inflammation dans l’hyper-insulinémie associée à l’obésité, les marqueurs de l’inflammation ont été comparés parmi les chevaux élancés ou idéal, normo-insulinémique (L-NI); les chevaux obèses, normo-insulinémique (O-NI); et les chevaux obèses, hyperinsulinémique (O-HI). Les concentrations du facteur nécrosant des tumeurs alpha (TNFα) étaient corrélées négativement avec le PCC. Lors de la comparaison des marqueurs de l’inflammation entre les groupes, la concentration de TNFα dans les muscles squelettiques était plus basse dans le groupe O-HI que dans les groupes O-NI ou L-NI. Chez les chevaux, ni l’inflammation systémique ou celle des muscles squelettiques ne semblent reliées positivement à l’obésité ou à l’hyper-insulinémie associée à l’obésité.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

In humans, obesity and Type-II diabetes are associated with a pro-inflammatory state (1–3). Obesity is caused primarily by accumulation of white adipose tissue (WAT), an important endocrine organ that secretes proteins known as adipokines, which regulate metabolism, coagulation, and inflammation (4). Key inflammatory adipokines secreted by WAT include the cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and the acute phase reactants, serum amyloid A (SAA) and C-reactive protein (CRP) (5–8). Circulating inflammatory cytokines, primarily TNFα, perpetuate the inflammatory state by activating intracellular stress kinases in tissues (9), with subsequent transcription of inflammatory cytokines and perpetuation of the pro-inflammatory state. Additional key cytokines that modulate the inflammatory response include IL-6 and IL-10. Interleukin-6 is an important mediator of the hepatic acute phase response and an adipokine and myokine involved in insulin signaling (10,11). Interleukin-10 is primarily an anti-inflammatory cytokine that counters the effect of IL-6 and TNFα.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) has both direct and indirect anti-inflammatory actions and has been used to treat several inflammatory conditions, including dermatomyositis, polymyositis, gout, and other forms of crystalline arthritis (12–14). Although historically the anti-inflammatory activity of ACTH has been primarily attributed to stimulation of glucocorticoid release (indirect actions), anti-inflammatory activity of ACTH in induced crystalline arthritis is maintained in adrenalectomized rats, which suggests a direct anti-inflammatory effect associated with binding to melanocortin receptors (15). Furthermore, in horses, ACTH is released from both the anterior and intermediate lobe of the pituitary along with other anti-inflammatory peptides, including alpha-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and beta-endorphin. As the concentration of ACTH parallels that of other pituitary-derived hormones, it can be used as a surrogate marker for pituitary anti-inflammatory hormone activity (16,17).

In contrast to studies in humans and in mice, research into obesity in horses has not demonstrated a consistent association between systemic inflammation and obesity. Initial studies found that obesity in horses was correlated with systemic inflammation (18,19), but these findings were confounded by failure to control for age in the obese population surveyed. In ponies with historical laminitis, circulating TNFα concentrations were not correlated with obesity (20). Furthermore, there were no differences in systemic markers of inflammation in equids fed to promote obesity with either a high fat or high glucose diet, compared to equids fed to maintain weight (21).

The role of systemic inflammation in equine hyperinsulinemia is similarly unclear. A previous study of hyperinsulinemic obese horses demonstrated a trend toward decreased circulating TNFα and decreased inflammatory cytokine expression when compared with lean controls, but no change in CRP (22). Interleukin-1β, IL-6, and TNFα plasma concentrations were not correlated with obesity or plasma insulin concentrations in another study, although SAA correlated with insulin concentrations and weakly with BCS (23). Horses with insulin dysregulation have a more prolonged upregulation of circulating inflammatory cytokine gene expression in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infusion than control horses, which suggests a pro-inflammatory state (24).

Despite multiple investigations into the relationship between systemic inflammation, obesity, and insulin regulation in horses, knowledge of tissue inflammation is limited. Inflammatory cytokine gene expression in adipose tissue of insulin-resistant horses was not significantly different than that of insulin-sensitive controls (25). The protein content of TNFα was increased in visceral adipose, but not in skeletal muscle or subcutaneous adipose of insulin-resistant horses compared to insulin-sensitive controls (26). Notably, in both of these studies, horses were stratified solely on the basis of dynamic insulin-sensitivity testing and were similar with respect to BCS.

We hypothesized that skeletal muscle inflammation is related to obesity and obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia in horses. To test this hypothesis, relationships between body condition score (as an indicator of obesity) and markers of local (skeletal muscle) and systemic inflammation were explored, including skeletal muscle gene expression of TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 and protein content of TNFα, and circulating concentrations of TNFα, SAA, and ACTH, a pituitary hormone with anti-inflammatory activity. Furthermore, markers of inflammation were compared among lean or ideal, normoinsulinemic (L-NI); obese, normoinsulinemic (O-NI); and obese, hyperinsulinemic horses (O-HI).

Materials and methods

Sample population

Adult horses donated to Oklahoma State University or the University of Tennessee were included in the study. Body condition score (BCS) was assessed in all animals (N = 35) by experienced observers, as previously described (23). All horses were considered to be free of systemic disease (aside from endocrine or metabolic disease) on the basis of physical examination. Blood samples and skeletal muscle biopsies were collected from all horses. All horses (N = 35, Table I) were included in correlation analysis evaluating relationships between body condition score and inflammation. In order to determine if obesity-associated inflammation has a role in hyperinsulinemia, inflammatory markers in obese animals (BCS ≥ 7) with hyperinsulinemia (O-HI) were compared to those of obese animals with normoinsulinemia (O-NI). Normoinsulinemic lean or ideal animals (BCS ≤ 5; L-NI) were included as controls (see Table I).

Table I.

Population characteristics by group, comparing lean or ideal, normoinsulinemic (L-NI), overweight, obese, normoinsulinemic (O-NI), and obese, hyperinsulinemic (O-HI) horses

| Lean or ideal, NI (n = 17) | Overweight (n = 5) | Obese, NI (n = 7) | Obese, HI (n = 6) | P-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breed | QH/Paint (n = 13) | QH/Paint (n = 3) | QH/Paint (n = 6) | Paso fino (n = 2) | |

| TB (n = 4) | Azteca (n = 1) | MFT (n = 1) | Morgan (n = 1) | ||

| Arab (n = 1) | Azteca (n = 1) | ||||

| QH (n = 1) | |||||

| TWH (n = 1) | |||||

| Agea | 15 ± 7 | 16 ± 5 | 11 ± 5 | 15 ± 4 | P = 0.30 |

| Gender | Gelding (n = 11) | Mare (n = 5) | Gelding (n = 4) | Gelding (n = 3) | |

| Mare (n = 6) | Mare (n = 3) | Mare (n = 3) | |||

| BCSb | 5 (4 to 5) | 6 | 8 (7 to 8) | 8.5 (8 to 9) | |

| Insulinb (μIU/mL) | 6 (5 to 14) | 13 (12 to 356) | 14 (5 to 8) | 195 (72 to 315) | P < 0.0001 |

| ACTHb (pg/mL) | 35 (28 to 61) | 28 (16 to 99) | 36 (19 to 43) | 37 (19 to 68) | P = 0.22 |

| TNFαb (pg/mL) | 1137 (431 to 2166) | 260 (40 to 1440) | 471 (40 to 1414) | 209 (98 to 874) | P = 0.08 |

| SAAb (ng/mL) (n = 25) | 35 (30 to 54) | 31 (28 to 52) | 54 (40 to 1322) | 27 (26 to 29) | P = 0.91 |

QH — Quarter Horse; TB — Thoroughbred; MFT — Missouri fox trotter; TWH — Tennessee walking horse.

Age is expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation).

Body condition score (BCS), insulin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and serum amyloid A (SAA) are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Reported P-values are for differences among groups.

Horses were not fed grain within 12 h of sample collection. Blood samples were collected between 9 am and 12 pm into tubes containing no anticoagulant and into tubes containing ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) and EDTA tubes were immediately placed on ice. All samples were centrifuged at 1200 × g for 10 min within 30 min of collection and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Semimembranosus muscle biopsies were collected antemortem (n =15) for horses that were not euthanized or within 15 min after euthanasia with pentobarbital (n = 20) using an open-biopsy technique as previously described (24). Muscle biopsy samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analysis. All samples were analyzed within 4 y of collection. Plasma and tissue samples have been demonstrated to maintain stability of ribonucleic acid (RNA) and protein for at least 5 y when stored at −70°C to −80°C (27,28). All samples were obtained in accordance with the institution’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hormone analysis

Concentrations of serum insulin (Coat-A-Count; Siemens, Tarrytown, New York, USA) were measured by radioimmunoassay and plasma ACTH concentrations were analyzed by chemiluminescent immunoassay (Immulite 1000; Siemens). All assays were previously validated for use in horses (29,30).

Muscle TNFα protein

Muscle sample homogenates were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (~50 mg in 1 mL PBS) using a tissue homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, USA). Homogenates were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. Supernatant protein concentration was quantified using a commercially available assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). Skeletal muscle TNFα was evaluated by an equine-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) that has previously been validated for use in horses (19). To validate the ELISA for use in skeletal muscle, a pooled sample with low TNFα concentration was spiked with a high TNFα standard. The pooled sample was then mixed with the spiked high sample at varying proportions and linearity was evaluated (r2 = 0.95, P = 0.005). Percent recovery was determined by spiking a pooled low homogenate sample with reconstituted standard at concentrations ranging from 62.5 to 1000 pg/mL. Recovery [mean ± SD (standard deviation)] was 80 ± 13%. Samples were analyzed in duplicate. Inter-assay coefficient of variation was 11.2% and intra-assay coefficient of variation was 8.4%.

Gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 30 mg of muscle tissue, using TRIzol extraction (Invitrogen, Eugene, Oregon, USA). The integrity of RNA was assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis. For quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), total RNA was treated with DNAse (Ambion, Crawley, Texas, USA) and complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) was transcribed according to the manufacturer’s directions (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA). Equine-specific primers (Supplementary Table I) were designed with Primer3 (primer3.sourceforge.net) from published equine sequence data (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore) and used to amplify TNFα, IL-10, and IL-6 messenger RNA (mRNA) using Beta actin (β-actin) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as housekeeping genes (Table I). It was determined that β-actin and GAPDH were the most stable housekeeping genes based on analysis with a commercially available software program (geNorm; Biogazelle, Zwijnaarde, Belgium). The geometric mean of both housekeeping genes was used to create a normalization factor that was applied to each gene to determine relative expression (RE).

Systemic inflammatory biomarkers

Serum amyloid A (TriDelta, Maynooth, County Kildare, Ireland) and TNFα (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) were measured in duplicate in plasma using commercially available ELISAs as previously described (19,31).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using commercially available software (SPSS, Armonk, New York, USA). Continuous variables were checked for normality using a Pearson d’Agostino normality test.

A Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between BCS and markers of inflammation. All horses (N = 35) were included in correlation analysis. Measurement of skeletal muscle inflammation included skeletal muscle gene expression of TNFα, IL-6, and IL-10 and protein expression of TNFα. Systemic inflammation was assessed by measuring TNFα and SAA. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was also included because pituitary hormones may have an anti-inflammatory influence in horses.

Population characteristics were compared among groups of horses [lean or ideal, normoinsulinemic (L-NI); obese, normoinsulinemic (O-NI); and obese, hyperinsulinemic (O-HI)]. All hormones and inflammatory biomarkers were log-transformed for normality. Tukey’s method was used to identify 2 SAA outliers [1744 pg/mL (O-NI) and 4000 pg/mL (L-NI] and 1 TNFα skeletal muscle gene expression (L-NI) outlier, all of which were removed from analysis. Age and insulin concentration were compared among groups using analysis of variance. Inflammatory markers [ACTH, serum amyloid A, TNFα protein expression (plasma and skeletal muscle), and skeletal muscle gene expression (IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα)] were compared among groups using analysis of covariance, with group as a factor and age as a covariate. When an interaction between group or age and an inflammatory marker was identified, a general linear model was used to characterize the interaction. For any marker that was different across groups, a Bonferroni’s post-hoc test was carried out to identify which groups were different. Significance for all variables was interpreted to exist at P < 0.05.

Results

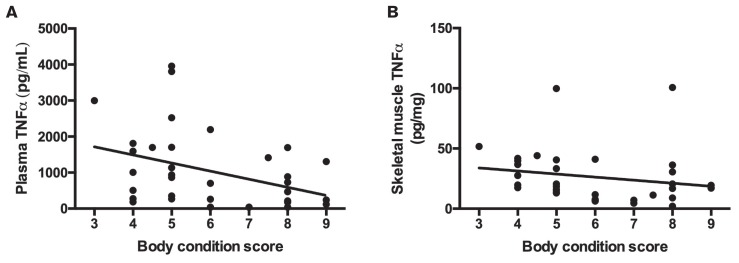

Population characteristics of all horses (N = 35) included in the correlation analysis are presented in Table I. Correlation analysis revealed significant negative associations between BCS and both circulating TNFα (r = −0.41, P = 0.02) and skeletal muscle TNFα (r = −0.37, P = 0.03; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between body condition score (BCS) and A — circulating tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (r = −0.41, P = 0.02) and B — skeletal muscle TNFα (r = −0.37, P = 0.03).

In order to determine how the presence of hyperinsulinemia altered the relationship between inflammation and obesity, further analysis was carried out among O-HI, O-NI, and L-NI horses. As expected based on inclusion criteria, insulin concentration was increased in O-HI horses compared to O-NI or L-NI horses. It was also found that insulin concentration was increased in the O-NI group compared to L-NI horses (P = 0.02). There were no differences in age among groups.

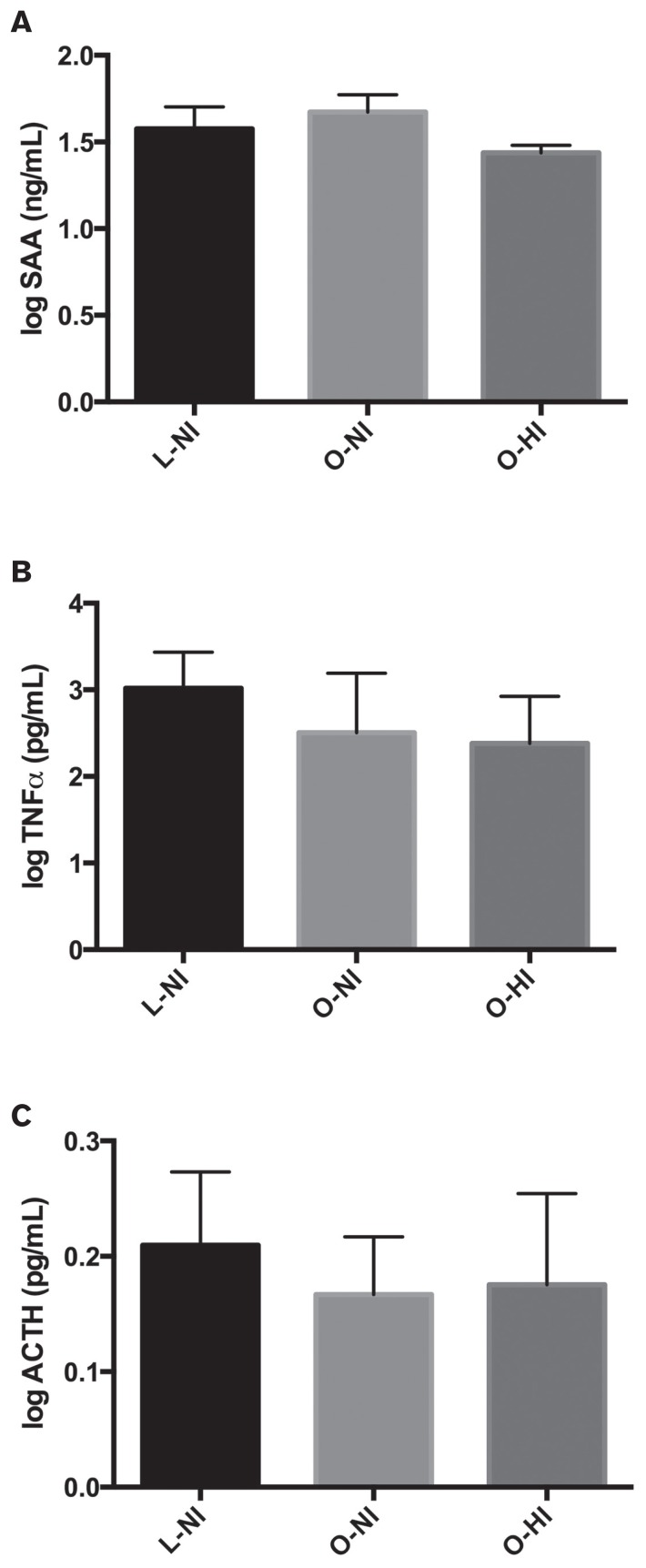

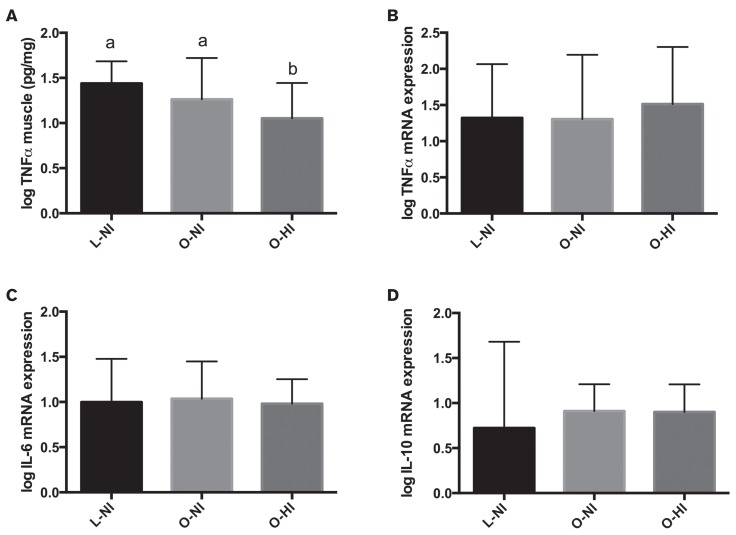

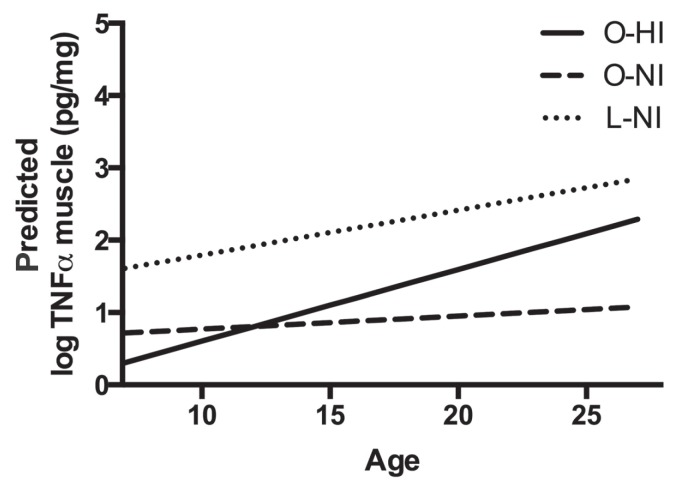

With regard to markers of systemic inflammation, there were no significant differences among groups in plasma SAA (P = 0.91), TNFα (P = 0.08), or ACTH (P = 0.22) concentrations (Figure 2). There was no influence of age or age-and-group interaction on any systemic marker. When evaluating skeletal muscle inflammation, there was a significant difference among groups with respect to skeletal muscle concentrations of TNFα (P = 0.006), with the O-HI horses having significantly lower concentrations compared to O-NI (P = 0.02) and L-NI horses (P = 0.006) (Figure 3). There was also a significant positive impact of age (P < 0.001) and an age-and-group interaction (P = 0.02) on concentrations of TNFα in skeletal muscle (Table II, Figure 4). When skeletal muscle gene expression was assessed, there were no significant differences among groups for expression of TNFα (P = 0.81), IL-6 (P = 0.44), or IL-10 (P = 0.14) (Figure 3). Skeletal muscle gene expression markers were not influenced by age or the age-and-group interaction.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of systemic inflammatory markers among groups [lean or ideal, normoinsulinemic (L-NI); obese, normoinsulinemic (O-NI); obese, hyperinsulinemic (O-HI)]. A — SAA; B — TNFα; and C — ACTH. Bars = mean ± standard deviation. There were no significant differences among groups in any systemic inflammatory marker.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of skeletal muscle inflammatory markers among groups. A — Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) concentration; B — TNFα gene expression; C — IL-6 gene expression, and D — IL-10 gene expression. Bars = mean ± standard deviation. Different superscripts (a,b) indicate significant difference among groups (P < 0.05). Only TNFα concentration differed among groups.

Table II.

Parameter estimates for group, age, and group-by-age interaction

| B | |

|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.171 |

| O-HI | −1.556 |

| O-NI | −0.579 |

| L-NI | 0 |

| Age | 0.018 |

| O-HI × age | 0.081 |

| O-NI × age | 0.044 |

| L-NI × age | 0 |

B — Estimated regression coefficient. O-HI — Obese, hyperinsulinemic; O-NI — Obese, normoinsulinemic; L-NI — Lean, normoinsulinemic.

Figure 4.

Interaction of age and group on concentration of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) in skeletal muscle.

Discussion

No positive associations between skeletal muscle or systemic inflammation and obesity were identified in this study. Furthermore, there were no significant increases in systemic or skeletal muscle inflammatory markers in O-HI compared to O-NI or L-NI horses. These findings suggest that neither skeletal muscle nor systemic inflammation is positively associated with obesity or obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia in horses.

Inflammation is considered to be a central component of obesity-associated insulin resistance in humans, with systemic and local (adipose and skeletal muscle) inflammation reported (32–34). There appear to be differences with respect to inflammation between metabolically healthy and unhealthy obese humans, with increased levels of inflammatory markers in metabolically unhealthy humans compared to healthy obese humans (35). Similar criteria for metabolically unhealthy obesity remain to be established for horses.

Hyperinsulinemia is a risk factor for laminitis (5), a painful condition that is an important concern for equine welfare. Therefore, in addition to looking at relationships between inflammation and obesity, we also chose to evaluate hyperinsulinemic obesity separately from normoinsulinemic obesity, since there may be mechanistic differences between these 2 groups.

Previous studies have yielded conflicting data with respect to the relationship between systemic inflammatory markers and body condition score or insulin concentration, with one study reporting positive associations between inflammatory markers and BCS or serum insulin concentration (23) and another study reporting no relationship between obesity and inflammation (36). Furthermore, induced weight gain in equids did not alter systemic SAA, TNFα, or adiponectin (21,37).

In our study, we found decreased systemic TNFα concentrations in association with obesity, with no change in systemic SAA or ACTH concentrations. Holbrook et al (22) previously documented a trend towards a decrease in circulating TNFα and decreased (IL-1, IL-6) or unchanged (TNFα) cytokine gene expression of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in obese hyperinsulinemic horses compared to controls. As TNFα promotes transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are important for leukocyte migration and immune response (38), the decrease in circulating TNFα and PBMC expression of inflammatory cytokines observed in obese horses may have implications for immune function.

Skeletal muscle gene transcription of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines was not altered with obesity in the horses of this study, while skeletal muscle TNFα protein expression was negatively associated with obesity. These findings indicate that skeletal muscle inflammation is not associated with obesity in horses as it is in humans (32,39). In addition, skeletal muscle inflammation was lower in O-HI compared to O-NI or L-NI groups, which suggests that skeletal muscle inflammation was not related to obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia.

As age is a potential confounder in evaluating inflammatory status, age was compared among groups and no significant differences were found. When examining both systemic and skeletal muscle inflammatory markers among groups, only skeletal muscle TNFα concentration was influenced by age, with skeletal muscle TNFα increasing with age. Previous studies have demonstrated an increase in systemic inflammation in aged, obese horses compared to aged controls (18) and an inverse relationship between systemic TNFα and insulin sensitivity in aged mares (19). Based on the findings of the present study, however, it appears that obesity and hyperinsulinemia independent of age do not contribute to a systemic or local pro-inflammatory phenotype.

Skeletal muscle inflammation was evaluated as a potential mechanism for hyperinsulinemia, as previous research in horses and other species has demonstrated that inflammation may lead to impaired insulin signaling in skeletal muscle, which may result in insulin resistance and subsequent hyperinsulinemia (26,32,40). In this study, we found a significant decrease in skeletal muscle TNFα protein concentration with obesity and obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia. Only the semi-membranosus muscle was evaluated, however, and these findings may not be consistent across other muscle groups. Previous studies have suggested that inflammatory state in healthy human skeletal muscle (41) and in rat skeletal muscle after dietary-induced obesity (42) may differ depending on the type of muscle fiber.

Skeletal muscle insulin resistance was not directly evaluated in this study and there could be other organs that contribute to hyperinsulinemia, including the insulin-sensitive tissues, liver and adipose, as well as the GI tract and pancreas. Previous research has suggested that adipose inflammation within select depots may be associated with insulin resistance in the horse (26), and it is possible that local inflammation could influence adipose insulin signaling and systemic insulin regulation without resulting in systemic or skeletal muscle inflammation. Furthermore, recent research suggests that the enteroinsulinar axis may play an important role in equine insulin dysregulation (43) and that tissue insulin resistance may be a secondary event.

In conclusion, despite what has been reported in other species, we did not find a positive relationship between skeletal muscle or systemic inflammation and obesity or obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia in horses. These findings suggest that skeletal muscle inflammation is not a key mechanism of obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia. Additional work is needed to determine the site and mechanism of hyperinsulinemia in obese horses.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary Table I.

Primer sequences used for gene expression analysis

| Primer | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | agtactccgtatggatcggcg | ccggactcgtcgtactcctg | Housekeeping gene |

| GAPDH | aagtggatattgtcgccatcact | aacttgccatgggtggaatc | Housekeeping gene |

| TNFα | agcccatgttgtagcaaacc | aaggctcttgatggcagaga | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-6 | ggatttcctgcagttcagcc | ccggactcgtcgtactcctg | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-10 | gatctcccaaatcccatcca | ggagagaggtaccacagggttt | Anti-inflammatory |

GAPDH — Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TNFα — Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6 — Interleuken-6; IL-10 — Interleuken-10.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kim Hill for technical assistance and Grace Kwong for statistical assistance. Funding was provided by the American Quarter Horse Foundation and the Oklahoma State University Research Advisory Committee.

References

- 1.Tantiwong P, Shanmugasundaram K, Monroy A, et al. NF-κB activity in muscle from obese and type 2 diabetic subjects under basal and exercise-stimulated conditions. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E794–E801. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00776.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plomgaard P, Nielsen AR, Fischer CP, et al. Associations between insulin resistance and TNF-alpha in plasma, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in humans with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2562–2571. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastard JP, Maachi M, Lagathu C, et al. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: Inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:347–355. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang RZ, Lee MJ, Hu H, et al. Acute-phase serum amyloid A: An inflammatory adipokine and potential link between obesity and its metabolic complications. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:29. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabro P, Chang DW, Willerson JT, Yeh ET. Release of C-reactive protein in response to inflammatory cytokines by human adipocytes: Linking obesity to vascular inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1112–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anty R, Bekri S, Luciani N, et al. The inflammatory C-reactive protein is increased in both liver and adipose tissue in severely obese patients independently from metabolic syndrome, Type 2 diabetes, and NASH. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1824–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:367–377. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yudkin JS, Kumari M, Humphries SE, Mohamed-Ali V. Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: Is interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trayhurn P, Drevon CA, Eckel J. Secreted proteins from adipose tissue and skeletal muscle-adipokines, myokines and adipose/muscle cross-talk. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2011;117:47–56. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2010.535835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daoussis D, Antonopoulos I, Yiannopoulos G, Andonopoulos AP. ACTH as first line treatment for acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis in 14 hospitalized patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritter J, Kerr LD, Valeriano-Marcet J, Spiera H. ACTH revisited: Effective treatment for acute crystal induced synovitis in patients with multiple medical problems. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:696–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine T. Treating refractory dermatomyositis or polymyositis with adrenocorticotropic hormone gel: A retrospective case series. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:133. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S33110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Getting SJ, Christian HC, Flower RJ, Perretti M. Activation of melanocortin type 3 receptor as a molecular mechanism for adrenocorticotropic hormone efficacy in gouty arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2765–2775. doi: 10.1002/art.10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beech J, Boston RC, McFarlane D, Lindborg S. Evaluation of plasma ACTH, alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, and insulin concentrations during various photoperiods in clinically normal horses and ponies and those with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235:715–722. doi: 10.2460/javma.235.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGowan T, Pinchbeck G, McGowan C. Evaluation of basal plasma α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and adrenocorticotrophic hormone concentrations for the diagnosis of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction from a population of aged horses. Eq Vet J. 2013;45:66–73. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2012.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams AA, Katepalli MP, Kohler K, et al. Effect of body condition, body weight and adiposity on inflammatory cytokine responses in old horses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;127:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.10.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vick MM, Adams AA, Murphy B, et al. Relationships among inflammatory cytokines, obesity, and insulin sensitivity in the horse. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:1144–1155. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treiber K, Carter R, Gay L, Williams C, Geor R. Inflammatory and redox status of ponies with a history of pasture-associated laminitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;129:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bamford NJ, Potter SJ, Harris PA, Bailey SR. Effect of increased adiposity on insulin sensitivity and adipokine concentrations in horses and ponies fed a high fat diet, with or without a once daily high glycaemic meal. Equine Vet J. 2016;48:368–373. doi: 10.1111/evj.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holbrook TC, Tipton T, McFarlane D. Neutrophil and cytokine dysregulation in hyperinsulinemic obese horses. Vet Immunol Immunopath. 2012;145:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suagee J, Corl B, Crisman M, Pleasant R, Thatcher C, Geor R. Relationships between body condition score and plasma inflammatory cytokines, insulin, and lipids in a mixed population of light-breed horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:157–163. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tadros EM, Frank N, Donnell RL. Effects of equine metabolic syndrome on inflammatory responses of horses to intravenous lipopolysaccharide infusion. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:1010–1019. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.74.7.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns TA, Geor RJ, Mudge MC, McCutcheon LJ, Hinchcliff KW, Belknap JK. Proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine gene expression profiles in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue depots of insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive light breed horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:932–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waller A, Huettner L, Kohler K, Lacombe V. Novel link between inflammation and impaired glucose transport during equine insulin resistance. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012;149:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis MR, Callas PW, Jenny NS, Tracy RP. Longitudinal stability of coagulation, fibrinolysis, and inflammation factors in stored plasma samples. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1495–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreasson A, Kiss NB, Juhlin CC, Höög A. Long-term storage of endocrine tissues at –80°C does not adversely affect RNA quality or overall histomorphology. Biopreserv Biobank. 2013;11:366–370. doi: 10.1089/bio.2013.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freestone JF, Wolfsheimer KJ, Kamerling SG, Church G, Hamra J, Bagwell C. Exercise induced hormonal and metabolic changes in Thoroughbred horses: Effects of conditioning and acepromazine. Eq Vet J. 2010;23:219–223. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1991.tb02760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins GA, Lamb S, Erb HN, Schanbacher B, Nydam DV, Divers TJ. Plasma adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) concentrations and clinical response in horses treated for equine Cushing’s disease with cyproheptadine or pergolide. Eq Vet J. 2002;34:679–685. doi: 10.2746/042516402776250333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pollock P, Prendergast M, Schumacher J, Bellenger C. Effects of surgery on the acute phase response in clinically normal and diseased horses. Vet Rec. 2005;156:538–542. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.17.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Garvey WT, Henry RR, Kern PA. The expression of TNF alpha by human muscle. Relationship to insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1111. doi: 10.1172/JCI118504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2409. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spranger J, Kroke A, Möhlig M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: Results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:812–817. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips CM, Perry IJ. Does inflammation determine metabolic health status in obese and nonobese adults? J Clin Endocrin Metab. 2013;98:E1610–E1619. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wray H, Elliott J, Bailey S, Harris P, Menzies-Gow N. Plasma concentrations of inflammatory markers in previously laminitic ponies. Eq Vet J. 2014;46:317–321. doi: 10.1111/evj.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suagee J, Burk A, Quinn R, Hartsock T, Douglass L. Effects of diet and weight gain on circulating tumour necrosis factor-α concentrations in Thoroughbred geldings. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2011;95:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2010.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roach DR, Bean AG, Demangel C, France MP, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. TNF regulates chemokine induction essential for cell recruitment, granuloma formation, and clearance of mycobacterial infection. J Immunol. 2002;168:4620–4627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plomgaard P, Nielsen AR, Fischer CP, et al. Associations between insulin resistance and TNF-alpha in plasma, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in humans with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2562–2571. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Alvaro C, Teruel T, Hernandez R, Lorenzo M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha produces insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by activation of inhibitor kappa B kinase in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17070–17078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plomgaard P, Penkowa M, Pedersen BK. Fiber type specific expression of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-18 in human skeletal muscles. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatt BA, Dube JJ, Dedousis N, Reider JA, O’Doherty RM. Diet-induced obesity and acute hyperlipidemia reduce IκBα levels in rat skeletal muscle in a fiber-type dependent manner. Am J Physiol Regul Integr and Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R233–R240. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00097.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Laat MA, McGree JM, Sillence MN. Equine hyperinsulinemia: Investigation of the enteroinsular axis during insulin dysregulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol and Metab. 2016;310:E61–E72. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00362.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table I.

Primer sequences used for gene expression analysis

| Primer | Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | agtactccgtatggatcggcg | ccggactcgtcgtactcctg | Housekeeping gene |

| GAPDH | aagtggatattgtcgccatcact | aacttgccatgggtggaatc | Housekeeping gene |

| TNFα | agcccatgttgtagcaaacc | aaggctcttgatggcagaga | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-6 | ggatttcctgcagttcagcc | ccggactcgtcgtactcctg | Pro-inflammatory |

| IL-10 | gatctcccaaatcccatcca | ggagagaggtaccacagggttt | Anti-inflammatory |

GAPDH — Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TNFα — Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6 — Interleuken-6; IL-10 — Interleuken-10.