Abstract

Osteoblasts are emerging regulators of myeloid malignancies since genetic alterations in them, such as constitutive activation of β-catenin, instigate their appearance. The LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5), initially proposed to be a co-receptor for Wnt proteins, in fact favors bone formation by suppressing gut-serotonin synthesis. This function of Lrp5 occurring in the gut is independent of β-catenin activation in osteoblasts. However, it is unknown whether Lrp5 can act directly in osteoblast to influence other functions that require β-catenin signaling, particularly, the deregulation of hematopoiesis and leukemogenic properties of β-catenin activation in osteoblasts, that lead to development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Using mice with gain-of-function (GOF) Lrp5 alleles (Lrp5A214V) that recapitulate the human high bone mass (HBM) phenotype, as well as patients with the T253I HBM Lrp5 mutation, we show here that Lrp5 GOF mutations in both humans and mice do not activate β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts. Consistent with a lack of β-catenin activation in their osteoblasts, Lrp5A214V mice have normal trilinear hematopoiesis. In contrast to leukemic mice with constitutive activation of β-catenin in osteoblasts (Ctnnb1CAosb), accumulation of early myeloid progenitors, a characteristic of AML, myeloid-blasts in blood, and segmented neutrophils or dysplastic megakaryocytes in the bone marrow, are not observed in Lrp5A214V mice. Likewise, peripheral blood count analysis in HBM patients showed normal hematopoiesis, normal percentage of myeloid cells, and lack of anemia. We conclude that Lrp5 GOF mutations do not activate β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts. As a result, myeloid lineage differentiation is normal in HBM patients and mice. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Tumor Microenvironment Regulation of Cancer Cell Survival, Metastasis, Inflammation, and Immune Surveillance edited by Peter Ruvolo and Gregg L. Semenza.

Keywords: Lrp5, β-catenin, Osteoblasts, High bone mass (HBM), Hematopoiesis, Leukemia

1. Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) can be found temporarily circulating or in secondary residence organs such as spleen and liver, but the majority of functional adult HSCs reside in the bone marrow (BM). It is within this compartment that they interact directly or indirectly with the different types of cells that comprise the HSC niche. Among this stromal population, cells of the osteoblast lineage are important determinants of the size of the niche and the function of hematopoiesis [1–10]. They influence HSC expansion and engraftment [3,10–13], promote quiescence [14–16], initiate HSC mobilization [17], regulate B-lymphopoiesis [18,19] and integrate sympathetic nervous system and HSC regulation [20]. More recently, osteoblasts have been directly implicated in the development of myeloid malignancies when global disruption of gene expression in osteoblast progenitors led to myelodysplasia (MDS) in mice [21], and constitutive activation of β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts induced acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in mice [22]. Conversely, leukemic myeloid cells were shown to stimulate osteoblast expansion into myeloproliferative cells that effectively support leukemic cells [23]. These observations suggested that functional changes in osteoblasts that are demonstrated by alterations in bone remodeling might eventually impact on their ability to regulate hematopoiesis.

LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) is a broadly expressed cell-surface receptor that affects bone formation. LRP5 loss-of-function mutations cause the autosomal recessive osteoporosis–pseudoglioma syndrome (OPPG), characterized by a severe decrease in bone formation [24], while gain-of-function (GOF) mutations cause the autosomal dominant high bone mass syndrome (HBMS) [25,26]. Studies in a variety of different mouse models have shown that Lrp5 potently regulates bone mass mainly through a gut-bone endocrine signaling system, in a non-cell autonomous manner, by suppressing the synthesis of gut serotonin, a powerful inhibitor of bone formation [27,28]. However, the homology of Lrp5 with a wingless co-receptor, has also led to the suggestion that Lrp5 may favor bone formation by acting as a co-receptor in the Wnt canonical signaling pathway in osteoblasts [24,25, 29,30]. This hypothesis has been challenged by previous and more recent findings showing that activation of canonical β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts, as opposed to Lrp5 activation, has no effect on osteoblast numbers and bone formation, but instead, increases bone formation by suppressing osteoclastogenesis and thus inhibiting bone resorption [31–36]. Consistent with this, it has been shown that Wnt16 is a β-catenin-activating ligand in osteoblasts which favors bone mass by inducing β-catenin-mediated suppression of bone resorption [37]. Although it appears more and more unlikely that the Lrp5 regulation of bone formation might rely on β-catenin activation in osteoblasts, it remains unknown whether Lrp5 can directly influence other osteoblast functions that require β-catenin signaling.

It has recently been shown that an activating mutation of β-catenin in mouse osteoblasts (Ctnnb1CAosb mice) invariably disrupts hematopoiesis altering the differentiation potential of myeloid and lymphoid progenitors and is sufficient to initiate the development of AML and death within 6 weeks of age [22]. These findings are relevant to human disease, since 38% of patients with AML, MDS, or AML arising from previous MDS have increased β-catenin signaling and nuclear accumulation in osteoblasts, suggesting that a similar mechanism may contribute to leukemia in humans. The demonstration that β-catenin activation in osteoblasts can induce AML raised the possibility that if there is indeed any link between Lrp5 signaling and β-catenin activation in osteoblasts, Lrp5 signaling would have detrimental effects on hematopoiesis in patients with the autosomal dominant HBMS (HBM, OMIM#601884) [38].

To address this important question, we have examined both in humans and in mouse models, whether Lrp5 and β-catenin interact in osteoblasts to deregulate hematopoiesis. We thus analyzed β-catenin activation in BM-derived osteoblasts, and hematopoiesis regulation in mice carrying a A213V amino acid mutation, that is equivalent to the A214V missense mutation reported in human patients with HBMS, the Lrp5A213V mice [30]. We have also analyzed β-catenin activation in circulating osteoblastic-lineage cells of patients carrying activating mutations in LRP5 known to cause the HBM. We found that Lrp5 gain-of-function does not activate canonical Wnt signaling (β-catenin activation) and that there is no alteration of hematopoiesis as a consequence of Lrp5 activating mutations, both in humans and mice.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and genotyping

The Lrp5A213V targeted mutation mice strain was purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The Ctnnb1CAosb have been previously described [22]. In each experiment, the mice used were all littermates of the same genetic background. All the protocols and procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of The Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Randomization was done according to genotype and blinding was applied during histological analysis.

2.2. Hematological measurements and peripheral blood morphology

For hematological measurements in mice, blood was collected by cardiac puncture and peripheral blood cell counts were performed on a FORCYTE hematology analyzer (Oxford Science). For morphological assessment, peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright–Giemsa stain (Sigma–Aldrich) for 10 min followed by rinsing in distilled H2O for 3 min. Images were taken using a 63× objective on a Leica microscope outfitted with a camera. Hematological measurements in patients and healthy controls were performed using standard techniques.

2.3. Antibodies and flow cytometry analysis

Freshly isolated BM cells from Lrp5A213V and corresponding WT littermates were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, 2 mM EDTA), filtered (40 μm), and kept on ice. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with a cocktail of primary conjugated antibodies as previously described [39]. The following cocktails of monoclonal conjugated antibodies were used for the myeloid population (defined as CD11b+ Gr-1+): CD11b (M1/70) and Gr-1 (RB6-8C5). For the hematopoietic progenitors, cells were first stained with lineage cocktail (CD3e; CD11b; CD45R/B220; Ter-119, Ly-6G, and Ly-6C) and then stained with c-kit (2B8), Sca-1 (D7), CD34 (RAM34), and CD16/CD32 (FcγRII/III; 2.4G2). LSK cells were defined as Lin− Sca-1+ c-kit+; GMP, CMP, and MEP cells were defined as CD34+ FcγRhigh, CD34+ Fcγlow, and CD34− FcγR− population from Lin− Sca-1− c-kit+ cells, respectively. The LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP were identified using the previously described LSK combination together with the SLAM markers CD150 (Sham) and CD48 (HM48-1), and defined as LSK CD150+ CD48−, CD50− CD48−, and CD150− CD48+, respectively. BM-derived osteoblasts were identified by surface expression of Lin− CD34− OCN+ (osteocalcin V-19, sc-18319) and intracellular expression of the RunX2+ osteoblast-specific transcription factor (RunX2 M-70, sc-10758). Stromal cells were isolated following previously published procedures [9,39–42], with minor modifications. Briefly, intact long bones were isolated, cleaned, and crushed with mortar and pestle to release the BM cells. Bone fragments were collected by filtration through a 40 μm cell strainer and extensively washed in HBSS with 2.5% FCS to remove non-adherent BM cells. The bone fragments were further minced and incubated at 37 °C with a 3 mg/mL solution of type IV collagenase (Worthington) and dispase II (Roche) in HBSS for 90 min, in a shaking water bath. The resulting population of endosteal stromal cells was stained for the following three populations: endothelial cells (Lin− CD45− Sca-1+ CD31+), mesenchymal cells (MSC; Lin− CD45− CD31− Sca-1+ CD51+), and endosteal osteoblasts (Lin− CD45− CD31− Sca-1− CD51+). In order to specifically detect activated (nuclear) β-catenin in osteoblasts, a non-phospho-β-catenin antibody that recognizes endogenous β-catenin protein when residues Ser33, Ser37, and Thr41 are not phosphorylated was used (Cell Signaling D13A1). Multicolor flow cytometry acquisition was performed in a BD LSRFortessa™ Cell Analyzer (Becton Dickinson) and analysis was done using the FlowJo software (Treestar). Cells were gated for size, shape, and granularity using forward and side scatter parameters. A fixable viability dye was used to exclude dead cells. The positive populations were identified as cells that expressed specific levels of fluorescence activity above the non-specific auto fluorescence of the isotype control.

2.4. Histology and immunohistochemistry

Murine long bones were collected from Lrp5A213V, Ctnnb1CAosb, and WT littermates mice, fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) following standard procedures. Heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) for immunohistochemical staining was done overnight at 65 °C in 10 mM Citrate buffer pH 6.0, 0.1% Tween-20. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched using 3% H2O2 in PBS. After blocking, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for either RunX2 or β-catenin (Santa Cruz #sc-10758, and #ab16051, Abcam, respectively) at 4 °C overnight. Signal was revealed using the avidin-biotin complex method (Vector Labs #PK6101), Horseradish peroxidase, and 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB, Vector Labs #SK4100). After permanent mounting, slides were analyzed with a brightfield microscope (Leica).

2.5. Patient samples

The patients with genetically and phenotypically verified HBM phenotype were recruited from hospital registry and have previously participated in other studies from our group [43]. The controls were recruited through personal contact. Each HBM patient was compared with age- and gender-matched controls. All participants gave written informed consent, and the local scientific ethical committee approved the study. After an overnight fast, the peripheral blood samples were collected in the morning in an EDTA-containing tube and immediately stored at 4 °C. The hematological parameters were carried out at the hospital Clinical Biochemistry Department and were collected from patients’ records. Osteocalcin surface staining was evaluated in bone marrow biopsies obtained from MDS patients after informed consent. Samples were stored in an IRB-approved Tissue Repository at Columbia University Medical Center and were used according to protocols approved by the institutional IRB.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Lrp5 gain-of-function mutant mice do not show β-catenin activation in osteoblasts

We have used a previously described Lrp5 gain-of-function (GOF) mutant mouse model, the Lrp5 A213V knock-in (Lrp5A/A, ‘A’ indicates the Lrp5 A213V gain-of-function allele) carrying the missense A213V amino acid mutation that is equivalent to the A214V missense mutation reported in human patients with HBM in the exon 3 of Lrp5 in all cells [38]. Homozygous mutant mice show an abnormally high bone density and heterozygous ones also show significantly increased bone mass and strength compared to WT mice. The A213V mutation encodes a mutant protein, expressed at normal (wild type, WT) levels and comparable to WT human LRP5 in their ability to transduce canonical Wnt signaling in vitro.

We first determined the concentration of BM-derived osteoblastic cells [44,45] in mice carrying either one (Lrp5A/+) or two copies (Lrp5A/A) of the A213V mutation versus WT littermates. Those were identified as Lin− CD34− RunX2+ OCN+ cells. Since osteocalcin is a secreted protein, we confirmed the specificity of the surface staining by showing specific osteocalcin staining in mouse calvaria-derived osteoblasts, the osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cell line, and in human osteoblasts derived from bone biopsies, but not in non-osteoblastic cells, such as mouse Lewis lung carcinoma or human A-431 epithelial cells (Sup. Fig. 1). In addition, we show that nearly all human bone marrow CD34− Lin− cells that stained positive for osteocalcin, stained positive also for the osteoblast-specific transcription factor RunX2 (Sup. Fig. 1B). Taken together, these observations suggest that osteocalcin staining is specific for osteoblasts and ostoeprogenitors.

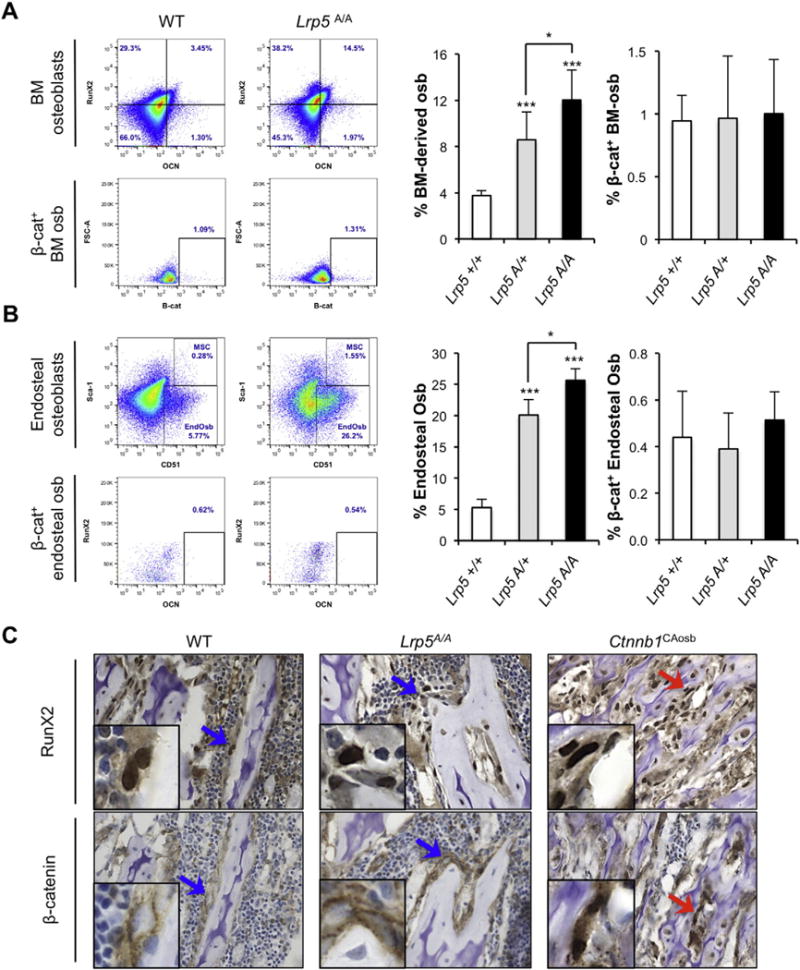

The Lrp5 GOF mutant mice carrying either one (Lrp5A/+) or two copies (Lrp5A/A) of the mutant allele, show a significant increase in the number of BM-derived osteoblastic cells (Lin− CD34− RunX2+ OCN+) compared to WT littermates (Fig. 1A). We also examined changes in the endosteal osteoblasts, since these are likely responsible for the high bone mass phenotype and are also the cells that represent osteoblastic niches [3,10,46–48]. Similar to our findings with BM-derived osteoblasts, the number of endosteal osteoblasts (defined as Lin− CD45− CD31− CD51+ Sca-1−) increased in both the heterozygous and the homozygous Lrp5 gain-of-function mice (Fig. 1B). These results further support and provide a quantitative proof of the previously described increase in bone mass, strength, and bone formation rate of Lrp5 GOF mice [30].

Fig. 1. Activating mutations in Lrp5 do not activate β-catenin signaling in osteoblast.

Representative flow plots of A) bone marrow (BM)-derived osteoblasts (osb; defined as Lin− CD34− RunX2+ OCN+ cells) and B) endosteal osteoblasts (defined as Lin− CD45− CD31−Sca-1− CD51+) in Lrp5 GOF (Lrp5A/A) and corresponding WT mice (top dot plots). Bottom plots for each population show non-phospho (active) β-catenin staining of the corresponding osteoblastic population. Right graphs show percentage of A) BM-derived osteoblast (left graph) and β-catenin activation state in those ones (right graph) in WT (n = 3), Lrp5A/+ (n = 7), and Lrp5A/A (n = 7) mice; and B) endosteal osteoblast numbers and their β-catenin activation state in WT (n = 3), Lrp5A/+ (n = 4), and Lrp5A/A (n = 3) mice; t-test p ≤ 0.05 (*) p ≤ 0005 (***). C) Immunohistochemistry of serial femur sections (5 μm) from WT, Lrp5A/A, and Ctnnb1CAosb mice stained for either RunX2 or β-catenin. Arrows point to the details shown in the inserts of the original 63× magnification. Top row shows Run×2 staining in osteoblasts of WT, Lrp5A/A (blue arrows), and Ctnnb1CAosb mice (red arrow); bottom row shows normal (membrane) β-catenin staining in osteoblasts from WT and Lrp5A/A (blue arrows) as compared to active (nuclear) β-catenin staining in osteoblasts from Ctnnb1CAosb mice (red arrow).

We next analyzed the β-catenin activation state in both osteoblastic populations (BM-derived and endosteal osteoblasts), as measured by flow cytometry using an antibody specifically recognizing non-phosphorylated (active, nuclear) β-catenin [22]. Neither A213V mice nor their WT littermates showed any evidence of β-catenin activation in their BM-derived osteoblasts (Fig. 1A) or in their endosteal osteoblasts (Fig. 1B). Similarly, immunohistochemical analysis performed on bone marrow of WT, GOF, and Ctnnb1CAosb mice for both RunX2 and β-catenin showed lack of β-catenin activation in the osteoblasts of the WT or GOF compared with the aberrant nuclear localization (activation) observed in several osteoblasts from the Ctnnb1CAosb mice (Fig. 1C). All together, these experiments do not provide any evidence that Lrp5 activating mutations in mice affect β-catenin signaling.

3.2. Lrp5 gain-of-function mice have normal hematopoiesis

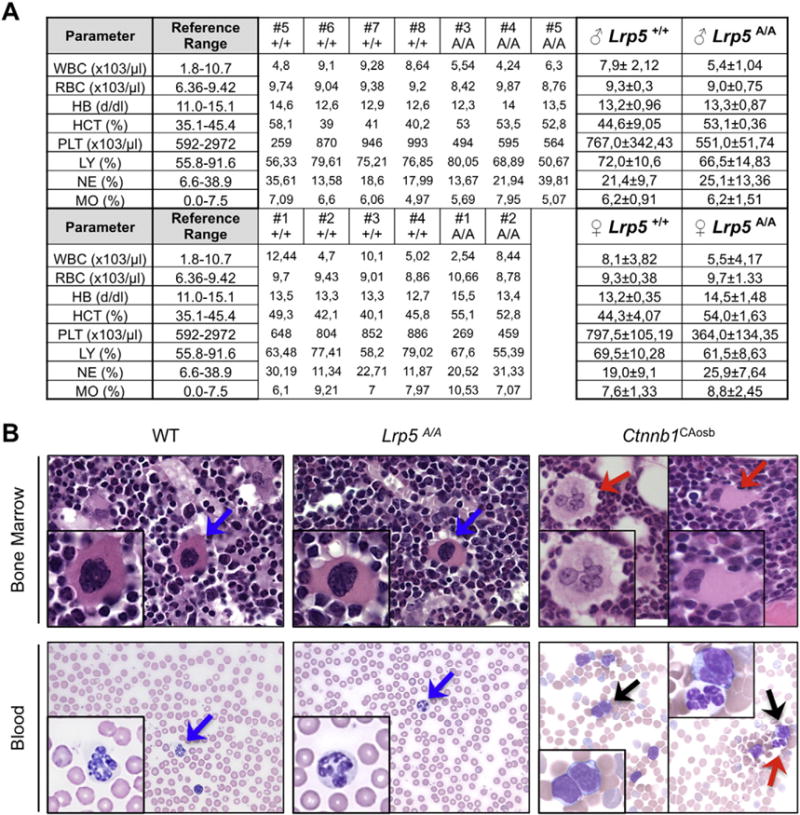

Cells of the osteoblast lineage affect the homing and number of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSC) [3,6,10], HSC mobilization, and lineage determination as well as B-cell lymphopoiesis [18,49]. Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that an activating mutation of β-catenin in mouse osteoblasts alters hematopoiesis by affecting the differentiation potential of myeloid and lymphoid progenitors, ultimately leading to development of AML [22]. Therefore, we analyzed hematopoietic function in Lrp5 GOF mutant mice and found that mice harboring the A213V mutation did not die prematurely and showed normal blood counts and regular levels of circulating blood cells, with no evidence of the anemia, monocytosis, neutrophilia, lymphocytopenia, or thrombocytopenia that are seen in Ctnnb1CAosb mice harboring an activating mutation of β-catenin in osteoblasts [22] (Fig. 2A). The presence of blasts and dysplastic neutrophils in the blood as well as infiltrates in the BM are all features of AML and characteristic of the Ctnnb1CAosb mice; none of these aberrations were found in the BM of the Lrp5A213V mice (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Normal peripheral blood counts and bone marrow cellularity in mice carrying high bone mass Lrp5 gain-of-function mutations.

A) Peripheral blood counts in Lrp5A/A and sex-matched WT littermates in 5-week-old mice. White blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), hemoglobin (HB), hematocrit (HCT), platelets (PL), lymphocytes (LY), neutrophils (NE), and monocytes (MO). B) Upper panel shows H&E staining images of bone marrow sections (63×). Inserts show in detail normal megakaryocytes in WT and Lrp5A/A mice (blue arrows) and dysplastic megakaryocytes, with hyperchromatic nuclei in Ctnnb1CAosb mice (red arrows). Bottom panel depicts blood smears, showing lack of blasts and presence of normal neutrophils in WT and Lrp5A/A mice (blue arrows) but immature monocytic blasts (black arrows) and a hypersegmented neutrophil (right panel, red arrow) in the Ctnnb1CAosb mice. Pictures are representative of n = 6 for WT, n = 6 for Lrp5A/A mice, and n = 4 for Ctnnb1CAosb.

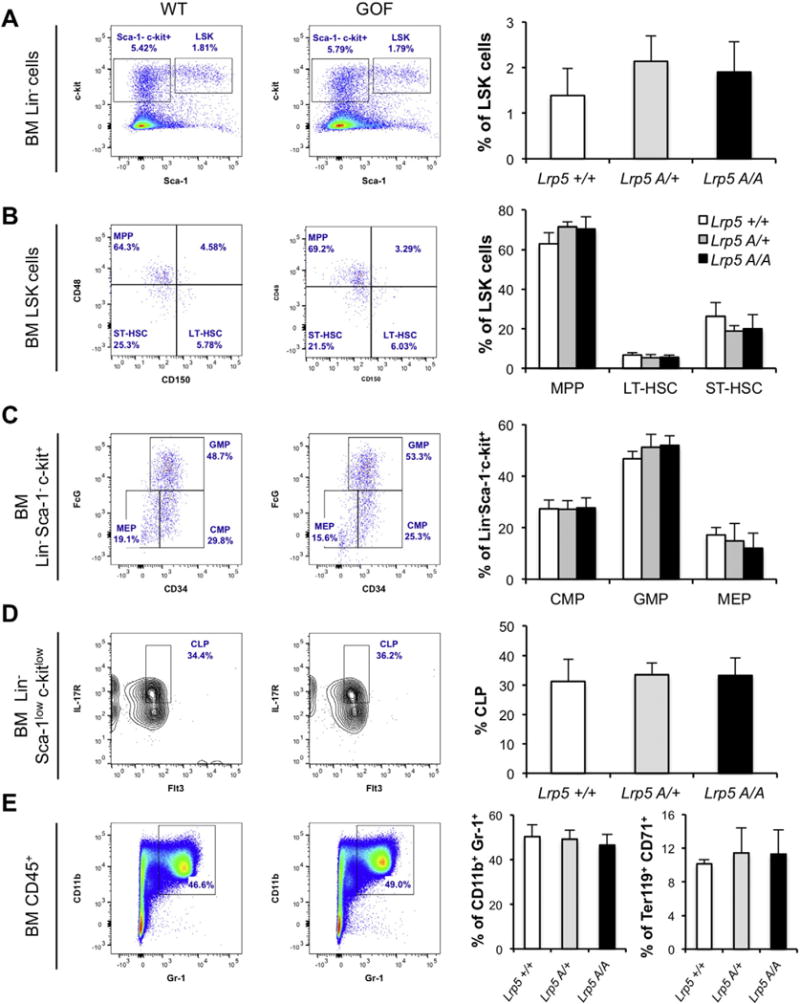

The BM hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) population, identified by the surface markers Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK cells), showed no significant changes between the Lrp5A/A, Lrp5A/+, and WT littermates (Fig. 3A) as opposed to the increase percentage of LSK cells seen in the Ctnnb1CAosb mice [22]. In the adult mouse, multipotent cells are contained in the LSK fraction of BM cells. Using the signaling lymphocyte activation molecules (SLAM) CD48 and CD150, along with the cell–cell adhesion factor CD34, we have dissected the immature hematopoietic stem and progenitor BM compartments by analyzing the percentage of LT-HSC, short-term HSC (ST-HSC), and multipotent hematopoietic progenitors (MPP) populations. The Lrp5 GOF mice did not show any differences in any of those populations compared to WT littermates (Fig. 3B). Within the Lin− Sca-1− c-Kit+ population, we analyzed the BM granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP), the common myeloid progenitor (CMP), and the megakaryocyte erythrocyte progenitor (MEP) subpopulations and found that all of them remained unaltered in Lrp5A/A and Lrp5A/+ compared to WT littermates (Fig. 3C), as opposed to what have been described for the Ctnnb1CAosb mice. The number of common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) identified as Lin− Sca-1low c-kitlow Flt3+ IL-7R+ was also not affected (Fig. 3D). Similarly, myeloid (CD11b+ Gr-1+) and erythroid cells (Ter119+ CD71+) were unaltered in Lrp5A/A and Lrp5A/+ compared to WT littermates (Fig. 3E) contrasting with the Ctnnb1CAosb mice, that show decreased erythroid cells and increase percentage of myeloid cells, a characteristic indicating a shift in the differentiation of HSCs to the myeloid lineage. Lrp5 GOF mice remained healthy for at least 6 months, the entire time they were observed. Although, we cannot rule out the possibility that hematopoietic deregulation may occur at an older age and that AML may develop with latency, these results show lack of abnormal myeloid differentiation in Lrp5A/A mice and indicate that Lrp5 GOF mutations do not alter hematopoiesis.

Fig. 3. Mice carrying high bone mass Lrp5 gain-of-function mutations have normal hematopoiesis.

A) Representative flow plots of LSK cells (defined as Lin− Sca-1+ c-Kit+), B) within the LSK gate (right upper gate on A), multipotent progenitor (MMP, CD48+ CD150−), long- and short-term hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSC, CD48− CD150+; ST-HSC, CD48− CD150−), C) within the Lin− Sca-1− c-Kit+ gate (upper left gate on A), progenitor cells (CMP, FcϒII/IIIRlow CD34+; GMP, FcϒII/IIIRhigh CD34+ and MEP, FcϒII/IIIR− CD34−). D) Within the Lin− Sca-1low c-kitlow cells, common lymphoid progenitors (CLP, Flt3+ IL7R+) and E) within the CD45+ leukocytes, myeloid (CD11b+ Gr1+) and erythroid (CD71+ Ter119+) populations in the BM of Lrp5A/A, Lrp5A/+, and matched WT mice. Right graphs show percentage of the indicated BM cells in WT (n = 3), Lrp5A/+ (n = 7), and Lrp5A/A (n = 7) mice. GMP: granulocyte/monocyte progenitors, CMP: common myeloid progenitor, MEP: megakaryocyte/erythroid progenitor.

3.3. Lack of β-catenin activation in osteoblasts of patients with HBM LRP5 gain-of-function mutations

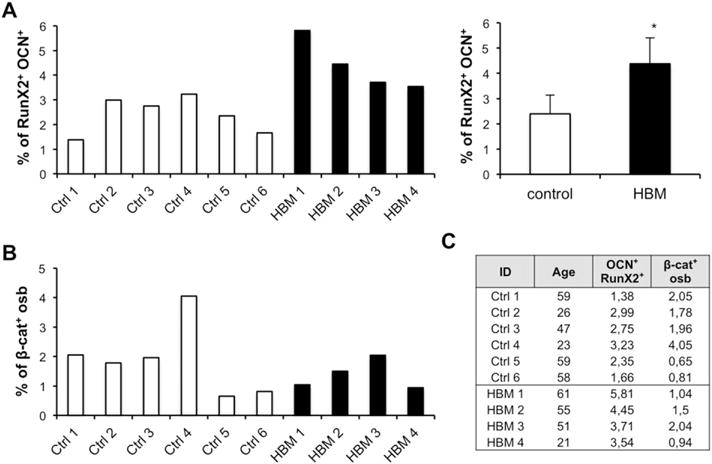

It increasingly appears that Lrp5 exerts its effects on bone mass through inhibition of the synthesis of the gut-derived hormone serotonin rather than through an osteoblast-autonomous Wnt-dependent mechanism [27]. Consistent with this notion, patients with an HBM phenotype due to a gain-of-function mutation of LRP5 (T253I) show reduced serum levels of serotonin [50]. To determine whether an LRP5 GOF mutation results in β-catenin activation in humans, we first analyzed the number and β-catenin activation state of the circulating osteoblastic cells in patients carrying the HBM T253I LRP5 GOF mutation and age-matched healthy control subjects. We have previously shown that circulating osteoblastic cells obtained from peripheral blood faithfully reflect the numbers, functions, and activation state of osteoblasts found in the bone, in bone disease and following treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH), a bone anabolic agent drug [44,51–54].

As shown in Fig. 4A, the number of circulating osteoblastic cells in the HBM patients was significantly higher than in healthy controls, while there was no difference in the β-catenin activation state of those osteoblasts (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that in humans, as well as in mice, Lrp5 activation does not activate β-catenin signaling in a measurable manner.

Fig. 4. Human LRP5 gain-of-function mutations do not activate β-catenin signaling in circulating osteoblasts.

A) Flow analysis of peripheral blood circulating osteoblasts (defined as Lin− CD34− RunX2+ OCN+ cells) in LRP5 HBM and age-matched control patients; left graph shows the percentage of cells in each patient and right panel the mean and standard deviation of the analyzed population; t-test p ≤ 0.05 (*). B) Quantification of the non-phospho (active) β-catenin state in peripheral blood circulating osteoblasts. C) Patients table. Control n = 6; HBM n = 4; OCN: osteocalcin; Osb: osteoblasts; β-cat: non-phospho (active) β-catenin.

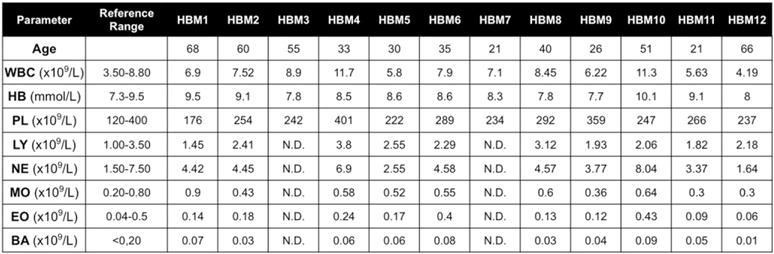

3.4. HBM patients harboring activating mutation in LRP5 show normal hematopoiesis

We have shown that 38% of patients with either MDS or AML show increase β-catenin signaling in their osteoblasts [22]. To examine whether LRP5 could be influencing any osteoblast functions that require β-catenin signaling, we analyzed hematopoiesis in HBM patients harboring the T253I activating mutation in LRP5. These patients showed no evidence of anemia, increased myelopoiesis, or overtly deregulated hematopoiesis (Fig. 5), further confirming that LRP5 is not responsible of the β-catenin activation in osteoblasts. Collectively, the observations made in humans carrying LRP5 HBM mutations point toward a difference between the consequence of LRP5 gain-of-function mutations and the known consequences of activation of β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts.

Fig. 5. HBM patients harboring the T253I activating mutation in LRP5 show no anemia and normal hematopoiesis.

Peripheral blood parameters in HBM (n = 12) LRP5 T253I subjects compared to reference range in healthy individuals.

4. Discussion

Together, human and mouse genetic studies have established that LRP5 is a major regulator of bone formation by osteoblasts [24–26,55]. Based on this property and the notion that alterations in osteoblast numbers correlate with changes in the number of LT-HSCs, defects in BM hematopoiesis, and the development of extramedullar hematopoiesis [3,4,19,46,56], we explored the possibility that activation of LRP5 gain-of-function mutations that lead to high bone mass in humans may also lead to alteration in hematopoietic capacity. To this end, we considered whether the mechanism of Lrp5 GOF induced increase in osteoblast numbers could also influence hematopoiesis.

Until recently, the molecular mechanisms whereby this surface receptor exerts this function were debated between activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in osteoblasts and regulation of serotonin synthesis in the gut. However, the possibility still existed that Lrp5 might influence in a β-catenin-dependent manner, other functions of osteoblasts. Our results show that despite the increase in the number of osteoblasts induced by the Lrp5 GOF mutations, both in humans and in mice, β-catenin activity is not increased in those osteoblasts. In agreement with the lack of β-catenin activation in their osteoblasts, mice and patients harboring a gain-of-function mutation in Lrp5 have normal hematopoiesis, with normal myeloid lineage differentiation and lack any signs of AML.

We note that the osteoblastic cell populations studied among humans and mice were not identical. Circulating osteoprogenitors from peripheral blood were used for patients, whereas bone marrow-derived and bone-lining osteoblasts were used for mice. The main reason for this discrepancy is that we were restricted in matching the source of osteoblastic cells between species because bone marrow biopsies are rarely performed in the LRP5 HBM patients. However, we and others have previously shown that circulating osteoprogenitors obtained from peripheral blood faithfully reflect the numbers, functions, and activation state of osteoblasts found lining the bone in several cohorts with low bone formation, including diabetic patients and hypoparathyroid subjects before and after treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH), a bone anabolic drug [52–54]. Circulating osteoblast lineage cells within the CD34− Lin− population are distinguished from myeloid and endothelial elements by the presence of OCN and correlate well with molecular and histomorphometric indices of bone formation; moreover, when these cells are cultured, they form mineralized nodules on bone forming surfaces [44,51,54].

The absence of evidence of activation of β-catenin in osteoblasts of mice and patients harboring a gain-of-function mutation in Lrp5 has to be interpreted cautiously. This being acknowledged, we note that patients with the HBM syndrome are not known to show a higher risk for developing hematological malignancies as compared to the general population and are not anemic. Collectively, our results and published observations [43–45,57–59] indicate that it is not possible to dissociate Lrp5 regulation of osteoblast numbers and gut-serotonin synthesis, while they do not provide evidence linking Lrp5 and β-catenin functions.

Cell differentiation along the osteoblast lineage is a complex, multi-step process, and manipulating the osteoblast or its progenitor at different stages of the osteoblast lineage can have utterly different repercussion on the functions and the influences of these cells in whole body physiology. Indeed, inactivation of β-catenin in the bipotential osteochondroprogenitor lineage can have different effect that in the osteoblast lineage. Whereas β-catenin activation in osteochondroprogenitors during skeletogenesis promotes osteoblastogenesis, its activation in mature osteoblasts of the adult mouse does not affect osteoblasts but suppresses osteoclastogenesis [60]. Similarly to the differences of β-catenin action on bone mass, activation of β-catenin signaling in osteocytes is sufficient to enhance components of the Notch signaling pathway but does not alter hematopoiesis or survival [61]. In addition to the fact that disparate outcomes of β-catenin activation depend on the stage of the osteolineage at which activation occurs, these observations may also reveal another important component in the mode of osteoblastic β-catenin-induced AML. They may indicate that cell-to-cell interaction between osteoblast and HSC is required for AML to develop. This possibility is further supported by the fact that osteoblast-induced AML development depends on increased expression of the Notch ligand Jagged-1 by osteoblasts which in turn activates Notch signaling in neighboring HSCs [22].

Similar to our observations showing that constitutive activation of β-catenin in osteoblasts is sufficient to drive the development of a transplantable AML-like disease with common chromosomal aberrations [22], other studies have highlighted the role of osteoblasts and other non-hematopoietic BM stromal elements in disease initiation. Loss of the miRNA processing enzyme Dicer-1 gene in mesenchymal/osteoblast progenitors can drive the development of an MDS-like disease with sporadic transformation to AML, which can be reverted following transplantation into WT mice [21]. Loss of Dicer-1 in osteoblast progenitors leads to reduced expression of the ribosome maturation protein Sbds gene, which is mutated in human Shwachman–Bodian–Diamond syndrome, a congenital BM failure disease with known leukemic predisposition. Deletion of the NF-κB inhibitor, I kappa B alpha (Iκ-Bα), in the liver, leads to the development of MPN [62]. The disease was non-transplantable and arose due to constitutive expression of the Notch ligand Jagged-1 by Iκ-Bα-deficient hepatocytes, driving the aberrant expansion of myeloid cells. Similarly, deletion of the retinoblastoma (Rb) gene or retinoic acid receptor gamma (Rarγ) was required in both hematopoietic and stromal cells in order to lead to a widespread MPN-like disease [63,64]. Likewise, deletion of the E3-ubiquitin ligase and canonical Notch ligand regulator mind-bomb-1 (Mib1) in stromal cells causes an MPN-like disease that is independent of Mib1 status in the hematopoietic compartment and can be reversed by constitutive activation of Notch signaling in the microenvironment [65]. Another recent study suggests that endothelial cells can also play a direct role in disease initiation. Deletion of Rbp-j (or Cbf1), a non-redundant downstream effector of the canonical Notch signaling pathway, in endothelial cells is sufficient to cause MPN-like disease leading to lethality [66]. Together, these studies in murine models demonstrate an initiating role for several HSC niche components in the development of a broad range of myeloid diseases.

These findings raise the question of whether alterations in the bone marrow niche are also involved in disease initiation in humans. The evidence is so far limited to correlative data obtained from patient samples. Consistent with the leukemogenic mouse model of overactive β-catenin signaling in osteoblasts driving Notch signaling in human AML cells, 38.3% of a cohort of 80 patients with MDS, AML, or MDS that progressed to AML showed increased nuclear β-catenin in their osteoblasts associated with increased Notch signaling in hematopoietic cells [22]. In support of a role for stromal upregulation of miR-155 in human MPN, overexpression of miR-155 was documented in BM aspirates from primary myelofibrosis (PMF) patients [67]. These data show that genetic alterations in the stromal population driving myeloid disorders in mice are detected in human tissues and could contribute to disease development. In addition, stromal cells isolated from patients with myeloid malignancies have been found to carry genetic mutations that are different from the initiating mutation(s) in the leukemic clone [68–70] suggesting that genetic changes could independently occur in BM niche cells during the course of the disease. In support of this notion, subjects undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantations can develop a rare donor-derived leukemia that is distinct from the classical recipient disease relapse [71], raising the possibility that an altered BM stromal compartment could directly contribute to or drive the development of a new leukemia in these individuals. Taking together, the observations in mouse models and human samples, are increasingly suggesting that genetic lesions acquired, perhaps over time, in HSC niche components, can independently contribute to the development of human myeloid disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR054447 and P01 AG032959 to SK) and the NovoNordisk foundation (to M. K.). Research reported in this publication was performed in the CCTI Flow Cytometry Core, supported in part by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, under awards S10RR027050. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors are grateful to the Molecular Pathology facility of the Herbert Irving Cancer Center of Columbia University Medical Center for preparation of tissue samples for histopathologic analysis.

Abbreviations

- GOF

Gain-of-function

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LSK

HSC-enriched Lin− Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells

- LT-HSC

Long-term hematopoietic stem cell

- ST-HSC

Short-term hematopoietic stem cell

- MPP

Multipotent progenitor

- CMP

Common myeloid progenitor

- GMP

Granulocyte macrophage progenitor

- MEP

Megakaryocyte erythrocyte progenitor

Footnotes

This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Tumor Microenvironment Regulation of Cancer Cell Survival, Metastasis, Inflammation, and Immune Surveillance edited by Peter Ruvolo and Gregg L. Semenza.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.11.037.

Transparency document

The Transparency document associated with article can be found, in the online version.

References

- 1.Levesque JP, Helwani FM, Winkler IG. The endosteal ‘osteoblastic’ niche and its role in hematopoietic stem cell homing and mobilization. Leukemia. 2010;24:1979–1992. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Il-Hoan O, Kyung-rim K. Concise review: multiple niches for hematopoietic stem cell regulations. Stem Cells. 2010 doi: 10.1002/stem.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvi LM, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stier S, Ko Y, Forkert R, et al. Osteopontin is a hematopoietic stem cell niche component that negatively regulates stem cell pool size. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1781–1791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Fattore A, Capannolo M, Rucci N. Bone and bone marrow: the same organ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heissig B, et al. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiozawa Y, et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1298–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI43414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celso C Lo, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2008;457:92–97. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch BJ, et al. Functional inhibition of osteoblastic cells in an in vivo mouse model of myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:832–836. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taichman RS, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support hematopoiesis through the production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1677–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Badri NS, Wang BY, Cherry, Good RA. Osteoblasts promote engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 1998;26:110–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson SK, et al. Osteopontin, a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and regulator of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1232–1239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai F, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshihara H, et al. Thrombopoietin/MPL signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and interaction with the osteoblastic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janzen V, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell responsiveness to exogenous signals is limited by caspase-3. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:584–594. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LD, Wagers AJ. Dynamic niches in the origination and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:643–655. doi: 10.1038/nrm3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan CKF, et al. Endochondral ossification is required for haematopoietic stem-cell niche formation. Nature. 2009;457:490–495. doi: 10.1038/nature07547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JY, et al. Osteoblastic regulation of B lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gs {alpha}-dependent signaling pathways. PNAS. 2008:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802898105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raaijmakers MHGP, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kode A, et al. Leukaemogenesis induced by an activating b-catenin mutation in osteoblasts. Nature. 2014;506:240–244. doi: 10.1038/nature12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schepers K, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasia remodels the endosteal bone marrow niche into a self-reinforcing leukemic niche. Stem Cells. 2013;13:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong Y, et al. LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyden LM, et al. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N Engl J Med. 2002:1–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little RD, et al. A mutation in the LDL receptor–related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high–bone-mass trait. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;70:11–19. doi: 10.1086/338450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadav VK, et al. Lrp5 controls bone formation by inhibiting serotonin synthesis in the duodenum. Cell. 2008;135:825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kode A, et al. Lrp5 regulation of bone mass and serotonin synthesis in the gut. Nat Med. 2014;20:1228–1229. doi: 10.1038/nm.3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kneissel M, Baron R. nm.3074. Nat Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui Y, et al. Lrp5 functions in bone to regulate bone mass. Nat Med. 2011;17:684–691. doi: 10.1038/nm.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer I, et al. Osteocyte Wnt/B-catenin signaling is required for normal bone homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3071–3085. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01428-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glass DA, Karsenty G. Canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblasts is required for osteoclast differentiation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:117–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato M, et al. Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:303–314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmen SL, et al. Essential role of β-catenin in postnatal bone acquisition. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21162–21168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Day TF, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill TP, et al. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling prevents osteoblasts from differentiating into chondrocytes. Dev Cell. 2005;8:727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Movérare-Skrtic S, et al. Osteoblast-derived WNT16 represses osteoclastogenesis and prevents cortical bone fragility fractures. Nat Med. 2014:1–14. doi: 10.1038/nm.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Wesenbeeck L, et al. Six novel missense mutations in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) gene in different conditions with an increased bone density. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:763–771. doi: 10.1086/368277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krevvata M, et al. Inhibition of leukemia cell engraftment and disease progression in mice by osteoblasts. Blood. 2014 doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semerad CL, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106:3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura Y, et al. Isolation and characterization of endosteal niche cell populations that regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116:1422–1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schepers K, et al. Activated Gs signaling in osteoblastic cells alters the hematopoietic stem cell niche in mice. Blood. 2012;120:3425–3435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-395418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frost M, et al. Levels of serotonin, sclerostin, bone turnover markers as well as bone density and microarchitecture in patients with high-bone-mass phenotype due to a mutation in Lrp5. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1721–1728. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, et al. Circulating osteoblast-lineage cells in humans. N Engl J Med. 2005:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, et al. Characterization of circulating osteoblast lineage cells in humans. Bone. 2007;40:1370–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Méndez-Ferrer S, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Omatsu Y, et al. The essential functions of adipoosteogenic progenitors as the hematopoietic stemand progenitor cell niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ding L, et al. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu J, et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;109:3706–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frost M, et al. Patients with high-bone-mass phenotype owing to Lrp5-T253I mutation have low plasma levels of serotonin. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:673–675. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khosla S, et al. Circulating cells with osteogenic potential. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:489–497. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manavalan JS, et al. Circulating osteogenic precursor cells in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3240–3250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Undale A, et al. Circulating osteogenic cells: characterization and relationship to rates of bone loss in postmenopausal women. Bone. 2010;47:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubin MR, et al. Parathyroid hormone stimulates circulating osteogenic cells in hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:176–186. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson ML, et al. Linkage of a gene causing high bone mass to human chromosome 11 (11q12-13) Am J Hum Genet. 1997:1–7. doi: 10.1086/515470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Visnjic D, et al. Hematopoiesis is severely altered in mice with an induced osteoblast deficiency. Blood. 2004;103:3258–3264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu W, et al. Patients with high bone mass phenotype exhibit enhanced osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of adipogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1720–1731. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu HJ, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (Tph-1)-targeted bone anabolic agents for osteoporosis. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4692–4709. doi: 10.1021/jm5002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yadav VK, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of gut-derived serotonin synthesis is a potential bone anabolic treatment for osteoporosis. Nat Med. 2010;16:308–312. doi: 10.1038/nm.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donald A, Glass II, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev Cell. 2005;8:751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tu X, et al. Osteocytes mediate the anabolic actions of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:E478–E486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409857112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rupec RA, et al. Stroma-mediated dysregulation of myelopoiesis in mice lacking IκBα. Immunity. 2005;22:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Walkley CR, et al. A microenvironment-induced myeloproliferative syndrome caused by retinoic acid receptor γ deficiency. Cell. 2007;129:1097–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walkley CR, Orkin SH. Rb is dispensable for self-renewal and multilineage differentiation of adult hematopoietic stem cells. PNAS. 2006:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603389103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim YW, et al. Defective Notch activation in microenvironment leads to myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2008:1–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu S, et al. Leukemia Research. Leuk Res. 2014;38:632–637. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norfo R, et al. miRNA-mRNA integrative analysis in primary myelofibrosis CD341 cells: role of miR-155/JARID2 axis in abnormal megakaryopoiesis. Blood. 2014:1–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-544197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blau O, et al. Chromosomal aberrations in bone marrow mesenchymal stroma cells from patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloblastic leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pontikoglou C, et al. Study of the quantitative, functional, cytogenetic, and immunoregulatory properties of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1329–1341. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Askmyr M, Quach J, Purton LE. Effects of the bone marrow microenvironment on hematopoietic malignancy. Bone. 2011;48:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wiseman DH. Donor Cell Leukemia: a review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:771–789. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.