Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to obtain reliable threshold measurements without a sound booth by using a passive noise-attenuating hearing protector combined with in-ear 1/3-octave band noise measurements to verify the ear canal was suitably quiet.

Design

We deployed laptop-based hearing testing systems to Tanzania as part of a study of HIV infection and hearing. An in-ear probe containing a microphone was used under the hearing protector for both the in-ear noise measurements and threshold audiometry. The 1/3-octave band noise spectrum from the microphone was displayed on the operator’s screen with acceptable levels in grey and unacceptable levels in red. Operators attempted to make all bars grey, but focused on achieving grey bars at 2000 Hz and above.

Study Sample

624 adults and 260 children provided 3381 in-ear octave band measurements. Repeated measurements from 144 individuals who returned for testing on 3 separate occasions were also analyzed.

Results

In-ear noise levels exceeded the minimal permissible ambient noise levels (MPANL) for ears not covered, but not the dB SPL levels corresponding to 0 dB HL between 2–4 kHz. In-ear noise measurements were repeatable over time.

Conclusions

Reliable audiometry can be performed using a passive noise-attenuating hearing protector and in-ear noise measurements.

Keywords: Audiometry, Octave band measurements

Introduction

Published standards for audiometric testing can be difficult to meet in the developing world and in field settings in general (Maclennan-Smith et al., 2013). We have been conducting a study in Dar es Salaam Tanzania on the effects of HIV-infection on hearing. For this study, we wanted to obtain reliable threshold audiograms, but financial and logistical limitations made the use of sound booths impractical. The custom, laptop-based system we designed for the testing uses a calibrated sound card/ear probe combination to perform the audiological tests. The in-ear probe contains 1 microphone and 2 speakers, and is similar to the system used in Saunders et al. (Saunders et al., 2012). We hypothesized that if we could use the in-ear microphone to display ear in-ear noise to the test conductor prior to starting the threshold test, we would be able to collect reliable threshold data using only a passive noise-attenuating hearing protector over the ears.

Methods

Hearing Testing Systems

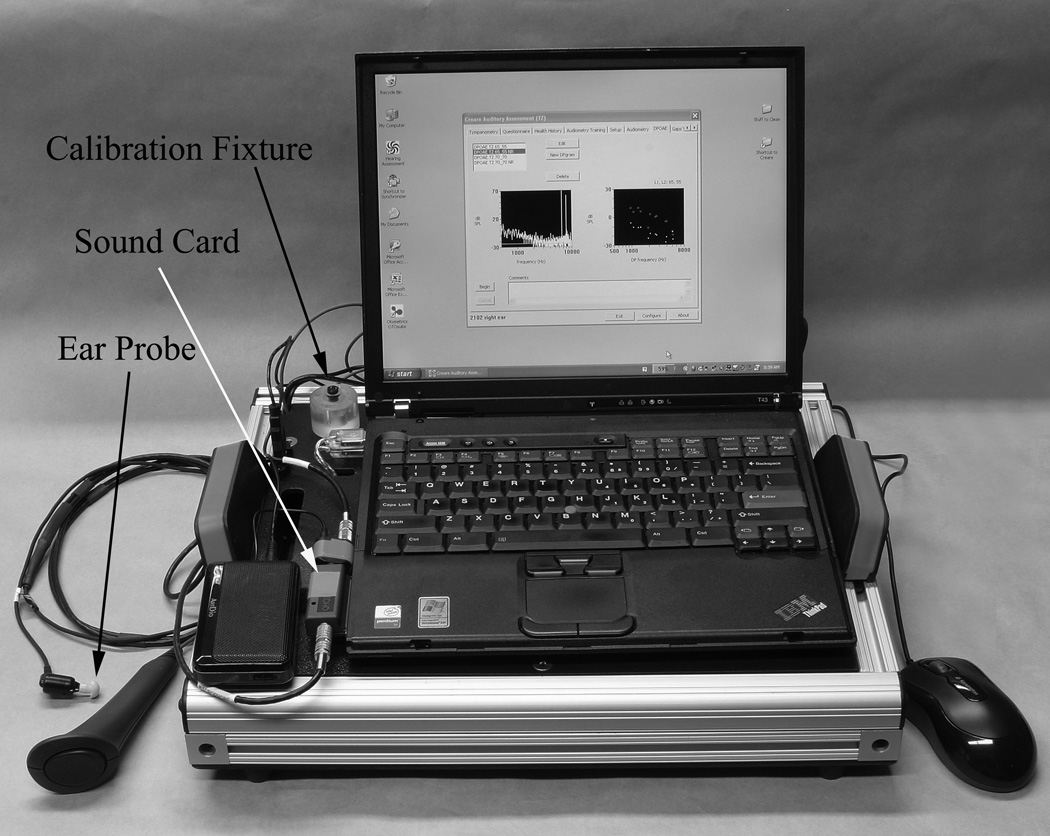

Custom-built, laptop-based hearing testing systems were used to perform the audiological tests—threshold audiometry, distortion production otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE) and gap detection testing (Figure 1). The systems used a modified PCMCIA audio sound card with 24 bit dynamic range and an up to 96kHz sampling rate (ECHO Indigo IO, Echo Audio, Santa Barbara, CA), interfaced with the ear probe used in the Grason-Stadler GSI 70 screener (Grason-Stadler Inc., Eden Prairie, MN). To maintain a consistent calibration for all devices, each probe and sound card were calibrated as a pair using a Brüel and Kjær Type 4157 Ear Simulator/Artificial Ear (Bruel and Kjaer Type, Nærum, Denmark). The system was calibrated in accordance with ANSI S3.6 – 2004, section 9.3, “Air Conduction, Insert Earphones” (American_National_Standard, 2004) with an acoustic coupler as described in ANSI S3.6 – 2004, 9.3.1, “Reference Levels in an Occluded Ear Simulator.” Linearity was established in the ear simulator up to 70 dB SPL. The noise floor of the system, measured in the artificial ear, was determined to be within 1 dB of the Maximum Permissible Ambient Noise Levels (MPANLS) for uncovered ears as established in ANSI S3.6 – 2004.

Figure 1.

Picture of the hearing testing systems used in the study. A sound card (ECHO Indigo IO, Echo Audio, Santa Barbara, CA), was placed in the PCMCIA slot of the laptop computer, and interfaced with an ear probe (the ear probe used is the same as the one used in the Grason-Stadler, GSI 70 DPOAE device (Grason-Stadler Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, part number 1770–325)). Prior to every measurement session the calibration of the system was checked with a 2 cc coupler.

The calibration curve for each pair was stored on the laptops. Before testing each subject on a given system, the calibration was checked with a 2 cc coupler. If the calibration did not match, the subject was tested with another system and the problem was investigated.

Subjects

The 1/3-octave band study included 3 main cohorts (a US cohort, a Tanzania cohort, and a cohort of normal hearing subjects to perform the biological calibration on the system)(Table 1). The adult Tanzania cohort included 624 subjects (400 female, 224 male) with an average age of 39 years. The pediatric cohort in Tanzania included 260 subjects (55% female) with an average age of 10 years. In the United States, we tested a convenience sample of 100 individuals (64% female, average age 39 years) to provide normative data on the methods used in the system. In Tanzania, the HIV+ adults and children were recruited at the DarDar Infectious Disease Center and Dartmouth Pediatric Program in Dar es Salaam respectively. HIV- subjects in Tanzania were recruited from a voluntary HIV testing and treatment center at Muhimbili National Hospital. The 100 subjects for normative data were recruited by word of mouth at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and tested by a member of the research team using the same equipment and procedures used in Tanzania (i.e. not in a sound booth). Ten additional normal subjects had been recruited and tested in the United States for the biological calibration of the probe for a previous study (Saunders, Jastrzembski et al., 2012). These subjects had threshold levels no poorer than 10 dB HL at each audiometric frequency.

Table 1.

Composition of the cohorts for the 1/3-octave band measurements. The study included 3 main cohorts, adults in Tanzania, children in Tanzania, and adults in the U.S. The numbers of individuals in each group and the number of 1/3-octave band measurements from each group are shown in the table.

| Adult | Adult Male |

Adult Female |

Pediatric | Pediatric Adult Earmuff |

Pediatric Child Earmuff |

Subjects with 3 tests |

US Subjects |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 624 | 224 | 400 | 260 | 168 | 92 | 144 | 100 |

| Measurements | 2590 | 791 | 1799 | 696 | 513 | 183 | 432 | 198 |

In-Ear Noise Measurements

After the probe was placed, the 1/3-octave band measurements were performed with a passive David-Clark Model 10A hearing protector with a noise reduction rating (NRR) of 23 dB (David Clark, Inc., Worcester, MA) over the ears. Initially, this was the only model of hearing protector available for both adults and children. To expand the options for pediatric testing a 3M Peltor Junior Earmuff with a NRR of 22 dB (3M Corporation, St. Paul, MN) was also acquired. Once this was available, if the David Clark hearing protector did not fit the pediatric subjects, they were tested using the 3M Peltor Junior Earmuff. The decision to use the pediatric headset was made based on the size of the child’s head, and also from the results from the one-third octave band testing. If the headset did not seal well, this was apparent from the one-third octave band testing results.

One-third octave bands were calculated following ANSI S1.11 – 2004 (R2009)

“Specification for Octave-Band and Fractional-Octave-Band Analog and Digital Filters” (American_National_Standard, 2009). The noise spectrum from the microphone was analyzed, and displayed as 1/3-octave bands on the operator’s screen. The plot of 1/3-octave bands shown to the operator displayed acceptable levels in grey and unacceptable levels in red. Levels below 30 dB SPL for frequencies <1000 Hz, below 25 dB SPL for frequencies between 1000–2000Hz, and below 20 dB SPL for frequencies ≥ 2000 Hz were displayed in grey. The operators were instructed to attempt to have all the bars grey, but if this was not possible, to focus on achieving grey bars at 2000 Hz and above.

Prior to the in-ear noise measurements, the operators also took measurements of the ambient noise level in the room using a sound level meter (Tenma Model 72–942, Tenma Test Equipment, Springboro, OH) reading in dBA. The study included a longitudinal component where participants returned every 6 months for repeated testing. In-ear noise measurements were made at each return visit.

Comparison Data

To assess whether the measured noise levels in the ear canal were acceptable, they were compared to 3 different sets of measurements. One comparison standard was the minimum permissible ambient noise levels (MPANL) with ears uncovered outlined by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI S3.1-1999) (American_National_Standard, 1999). The ears uncovered standard was used since this represents the ambient level in a room where testing is being performed without an in-ear probe or hearing protector/earmuff. These levels roughly indicate roughly how quiet the ambient noise levels in the ear canal would need to be for the testing.

Another standard used in this study were measurements of noise levels in a sound booth taken using the same system used in Tanzania. To acquire these measurements a calibrated testing system was placed in an IAC Sound Booth (IAC 404A, Industrial Acoustic Company, Bronx, NY) located in our laboratory in the United States, and 1/3-octave band measurements were collected in triplicate. These measurements represented what the ambient noise levels would be in a typical sound booth, if a sound booth had been used for the testing.

The 1/3 octave band levels from Tanzania were also compared to the sound level corresponding to 0 dB HL for the system. Because the probe used for this study did not have published reference equivalent threshold sound pressure levels (RETSPLs), we had determined these levels previously in a separate study with normal hearing subjects. The protocol generally followed the recommendations for the threshold determination method outlined in Annex D of ANSI S3.6-2004-“Specification for Audiometers” (American_National_Standard, 2004) to transfer of reference equivalent threshold values from a standard reference earphone to an earphone of a different type.

For this study, ten normal hearing subjects with threshold levels no poorer than 10 dB HL at each audiometric frequency were recruited. In a sound booth, the subjects had their thresholds determined using a calibrated GSI-16 audiometer using the Hughson-Westlake method. They then performed threshold audiometry on the calibrated laptop-based system, and the dB SPL value corresponding to their threshold at 500, 1000, 2000, 4000 and 6000 Hz was determined. The average dB SPL values corresponding to 0 dB HL from the 10 subjects were determined and used as the RETSPL for the laptop-based system.

Data were also collected on 100 normal subjects in the United States using an identical testing system. Similar to the test environment in Tanzania, these data were collected without a sound booth in a room where other, typical activities were taking place.

Data Analysis

The 1/3-octave band data were divided into groups (adult, pediatric, male, female) and the groups were compared using a one-way ANOVA. Results were considered significantly different for p values <0.05. For the 144 subjects with repeat visits, the standard deviation of the mean from the 3 visits was calculated. The 1/3-octave band results do not include a band centered at 6000 Hz, the closest to 6000 Hz is the band centered at 6300 Hz. To simplify the data presentations, results for 6000 Hz from the RETSPLs were plotted with the 1/3-octave band data from 6300 Hz.

Results

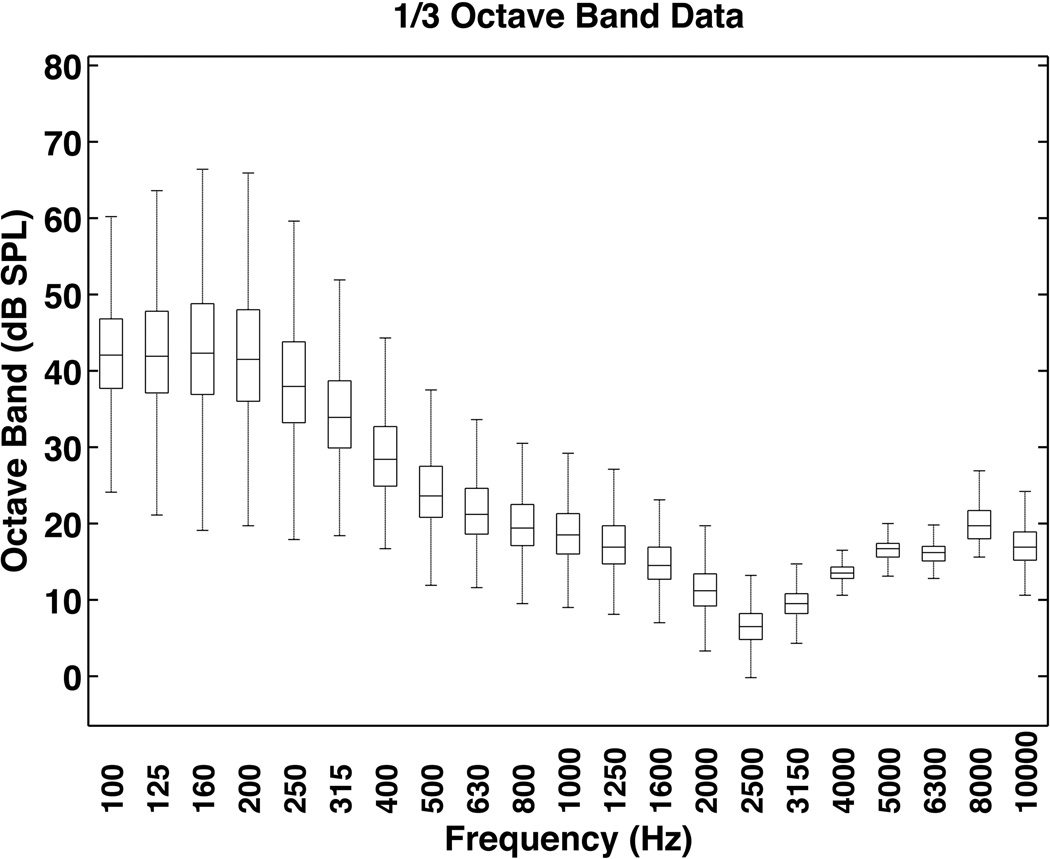

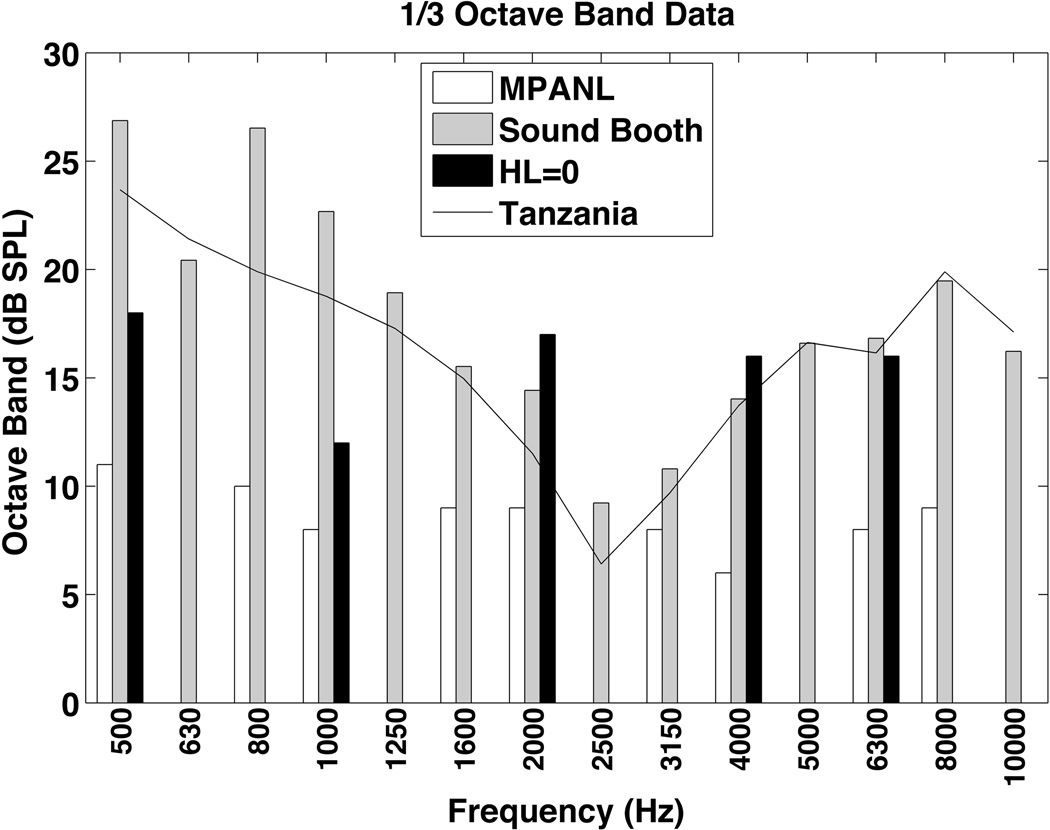

Figure 2 shows the overall results from the 1/3 octave band testing. Median values at 1/3-octave bands above 1000 Hz were below 20 dB. The average noise level in the room was 47.8 dBA. The comparison of the overall octave band results to the MPANL, sound booth and RETSPL results are shown in Figure 3. The overall in-ear octave band measurements are similar to the octave band measurements within a sound booth. At 2000 and 4000 Hz the RETSPL values are greater than the in-ear octave band SPL levels.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of 3381 in-ear 1/3-octave band measurements from 624 adults and 260 children. The box represents the middle quartiles of data (i.e. 50% of the data are within the box). The line in the box represents the median value. The lines leading from the box go to the minimum and maximum values (excluding outliers). Median values at octave bands between 1000–6300 Hz were below 20 dB.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the measured 1/3-octave band levels with ANSI MPANL levels, levels measured with the same system in a sound booth, and the SPL levels corresponding to an HL=0. At 2000 and 4000 Hz the median 1/3 octave band level was less than the HL=0 level, indicating that reliable threshold audiograms could be acquired at these frequencies. For reference, the inherent noise in the probe microphone by octave band in dB SPL was 500Hz=17, 1000Hz=13.5, 2000Hz=8.5, 4000Hz=13.

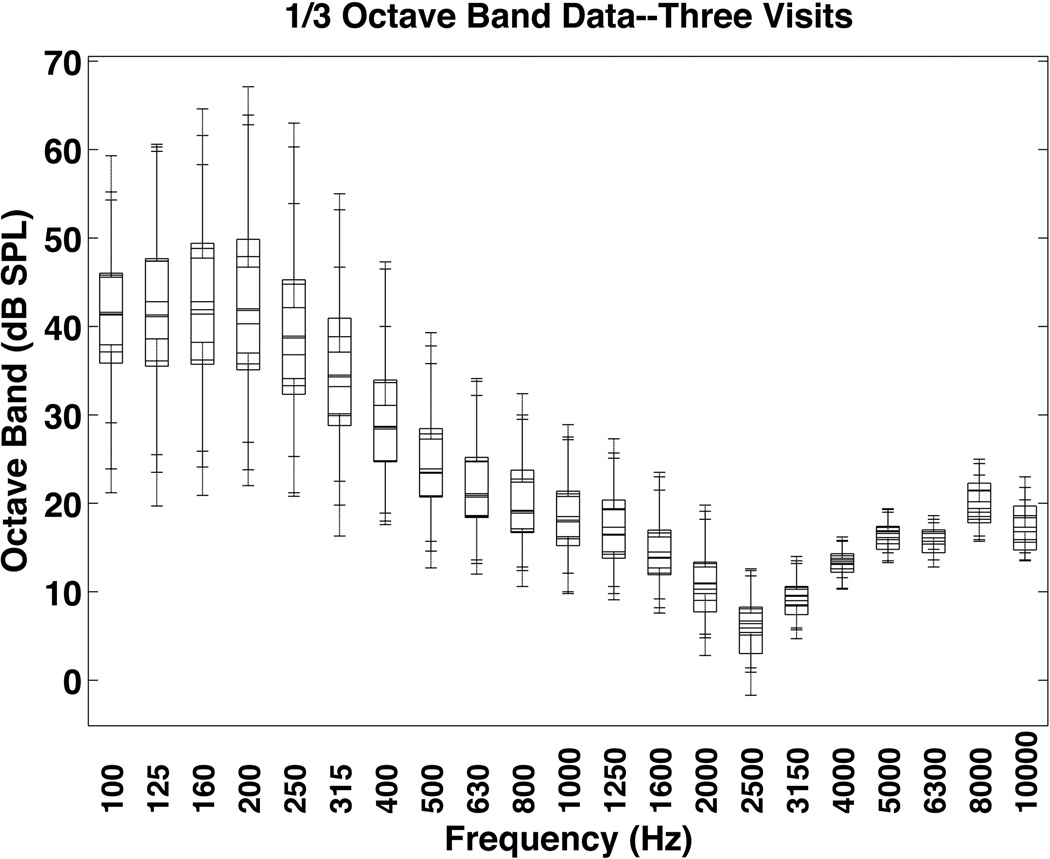

To assess whether these measurements were repeatable over time, a separate analysis was performed on 144 subjects who had returned for at least 3 visits. The results are shown in Figure 4. The standard deviation of the 3 measurements at the 1/3-octave bands centered at 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz is shown in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of repeated 1/3-octave band measurements from 144 subjects who returned for 3 visits approximately 6 months apart. Overall, the measurements were repeatable over time.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation for repeated octave band measurements made approximately 6 months apart from 144 subjects.

| 500 Hz | 1000 Hz | 2000 Hz | 4000 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 24.8 | 18.5 | 10.4 | 13.1 |

| Standard Deviation |

5.8 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 1.5 |

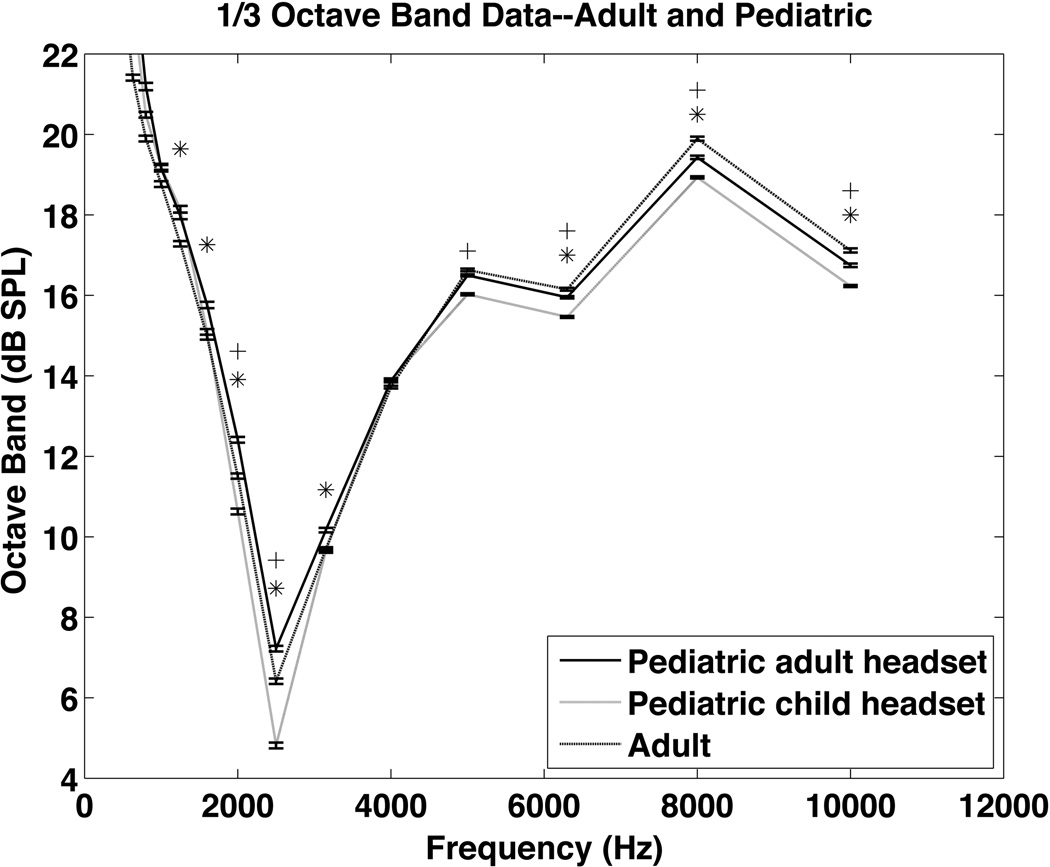

Initially, a comparison of the 1/3-octave band measurements between the adult and pediatric subjects revealed that the pediatric 1/3-octave band measurements were significantly higher than the adult measurements. This had been noted in the field by the study operators, and was thought to be due to a poor fit of the earmuff on some of the pediatric subjects (when the study began, only the adult hearing protector was available for testing). A smaller, better fitting, earmuff was provided for the pediatric subjects. Figure 5 shows the adult and pediatric 1/3 octave band data. The pediatric data are separated into the 1/3 octave band data collected using the initial adult earmuff, and then after the institution of the better-fitting pediatric hearing protector.

Figure 5.

1/3-octave band data comparing adult and pediatric measurements. Data presented as mean ± SEM. Initially, 1/3-octave band levels were significantly higher for the pediatric subjects (top line). This difference was minimized when a better fitting pediatric earmuff was used (middle line). Asterisks show significant differences at p<0.05 between adult and pediatric groups with the adult earmuff. Crosses show significant differences at the p<0.05 level between the pediatric group with the adult earmuff and the pediatric group with the pediatric earmuff.

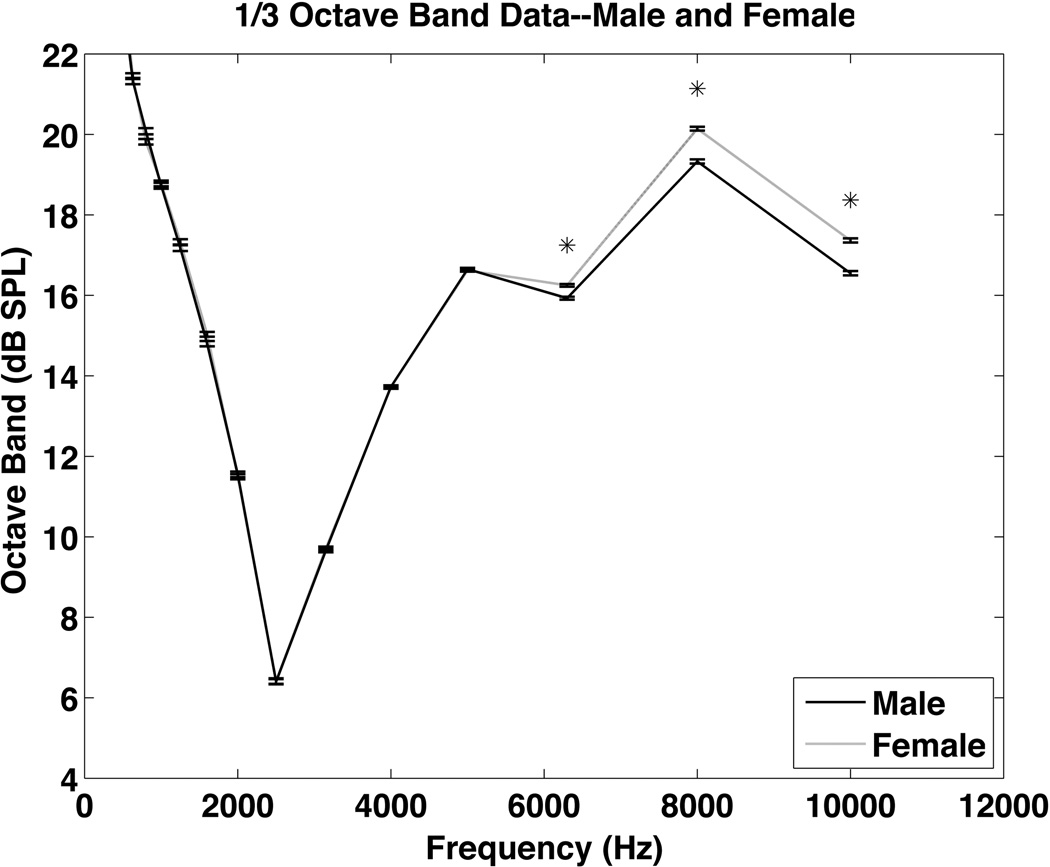

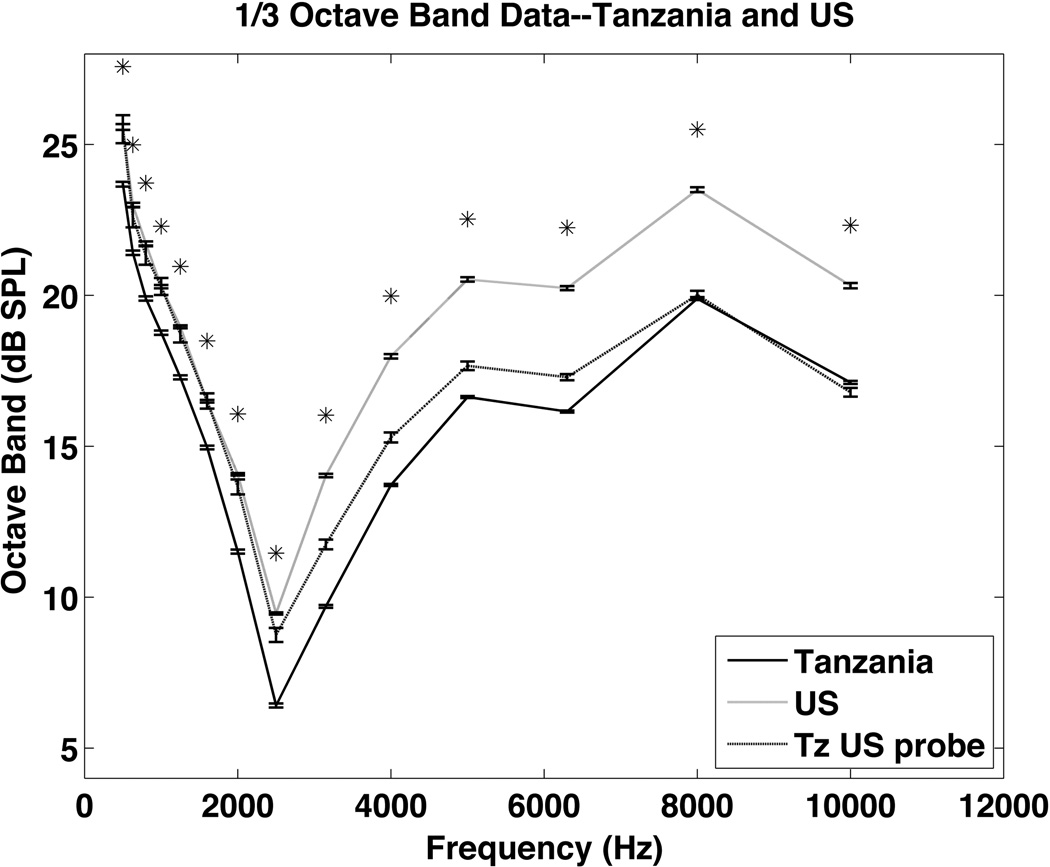

One-third octave band measurements of noise were slightly, but significantly, higher for female subjects at 6000 and 8000 Hz (Figure 6). One-third octave band data collected on 100 subjects in the U.S. showed significantly higher 1/3-octave band levels compared to the mean of the Tanzania results (Figure 7). The data and p-values for the adult-pediatric, male-female and Tanzania-U.S. comparisons are shown in Table 3. The card and probe combination used in the U.S. for testing was subsequently used in Tanzania for testing there. The data from Tanzania from that card/probe combination are significantly lower than the U.S. data, indicating that the testing area in the U.S. was noisier at the testing frequencies than the Tanzania location (the average ambient noise level recorded in the U.S. was 50 dBA).

Figure 6.

1/3-octave band measurements from male and female adults. 1/3-octave band levels were significantly higher for females at 6300 Hz and above. Asterisks show significant differences between groups at the p<0.05 level.

Figure 7.

1/3-octave band measurements from 100 subjects tested in the U.S. compared to the Tanzanian test population. When the same card and probe used for the U.S. testing was subsequently used in Tanzania, the noise levels were significantly lower. The differences likely reflect the different sound environments in the two test conditions. Asterisks show significant differences between the U.S. and Tanzania groups at the p<0.05 level.

Table 3.

1/3-octave band means and p-values for the adult-pediatric, male-female, and Tanzania-U.S. comparisons.

| 500 | 630 | 800 | 1000 | 1250 | 1600 | 2000 | 2500 | 3150 | 4000 | 5000 | 6300 | 8000 | 10000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | 23.68 | 21.41 | 19.90 | 18.76 | 17.28 | 14.96 | 11.51 | 6.41 | 9.70 | 13.72 | 16.63 | 16.15 | 19.89 | 17.12 |

| Pediatric- adult earmuff |

27.75 | 24.32 | 21.19 | 19.16 | 17.97 | 15.76 | 12.41 | 7.22 | 10.17 | 13.87 | 16.50 | 15.95 | 19.43 | 16.75 |

| Pediatric- child earmuff |

26.90 | 23.24 | 20.49 | 19.19 | 18.14 | 15.09 | 10.63 | 4.82 | 9.66 | 13.90 | 16.03 | 15.46 | 18.93 | 16.23 |

| P Adult/Ped adult earmuff |

<.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.053 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.109 | 0.135 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.009 |

| P Adult/Ped child earmuff |

<.001 | <.001 | 0.061 | 0.172 | 0.005 | 0.626 | 0.003 | <.001 | 0.843 | 0.236 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| P Ped adult/child earmuff |

0.119 | 0.020 | 0.102 | 0.927 | 0.688 | 0.079 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.064 | 0.861 | 0.001 | <.001 | 0.013 | 0.009 |

| Male | 23.35 | 21.33 | 20.08 | 18.72 | 17.17 | 14.80 | 11.55 | 6.40 | 9.66 | 13.73 | 16.65 | 15.93 | 19.33 | 16.55 |

| Female | 23.83 | 21.45 | 19.82 | 18.78 | 17.33 | 15.03 | 11.49 | 6.42 | 9.71 | 13.71 | 16.62 | 16.25 | 20.14 | 17.37 |

| P value | 0.017 | 0.506 | 0.135 | 0.744 | 0.357 | 0.126 | 0.708 | 0.915 | 0.606 | 0.896 | 0.721 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Tanzania | 23.68 | 21.41 | 19.90 | 18.76 | 17.28 | 14.96 | 11.51 | 6.41 | 9.70 | 13.72 | 16.63 | 16.15 | 19.89 | 17.12 |

| US | 25.58 | 22.99 | 21.72 | 20.29 | 18.96 | 16.49 | 14.07 | 9.46 | 14.03 | 17.98 | 20.53 | 20.24 | 23.50 | 20.32 |

| P Value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

Discussion

The results show that an adequate environment for threshold audiometry can be created without a sound booth. These results support the findings of Swanepoel et al. and Maclennan-Smith et al., who also showed that reliable audiometry could be performed by monitoring ambient room noise levels (Swanepoel de et al., 2010; Maclennan-Smith, Swanepoel de et al., 2013). By using an audiometer with microphones both on and underneath the circumaural earpieces, they obtained reliable audiograms without sound-attenuating booths.

Providing the 1/3-octave band data to the operators allowed for threshold-based testing with in-ear noise levels low enough at important speech recognition frequencies (2000–4000 Hz) to provide reliable threshold values. On average, 1/3-octave band noise levels at frequencies at and below 1000 Hz were higher than RETSPL values. The data from within the ear canal also provided additional information not available with standard ambient noise level monitoring. The 1/3-octave band testing provided the information the operator needed to optimize earmuff fit to provide the lowest possible noise environment in the ear. The ability to provide a good earmuff fit at each visit may be one reason why the testing was repeatable over time. By using the 1/3 octave-band feedback, the operator could create a good hearing protector fit at each visit.

The measured 1/3-octave band levels were higher than the MPANL levels at all frequencies. One possible explanation for this is the limitations on the microphone used to make the measurements. To measure 1/3-octave band levels at low levels needed for the MPANL measurements requires a very low noise microphone optimized to make these low-level measurements. The microphone in the ear probe used in the study does not meet the specifications needed to make measurements at those low levels (for reference, the inherent noise in the probe microphone by octave band in dB SPL was 500Hz=17, 1000Hz=13.5, 2000Hz=8.5, 4000Hz=13). The measurements made with the microphone in the sound booth (Figure 3), most likely represent the best real-world performance of the microphone for measuring ambient noise levels. The fact that the 1/3-octave band levels under the earmuff were similar to those measured in the sound booth in the 500–6000 Hz range is encouraging.

These results support the use of in-ear noise measurements to assist with threshold-based testing. The tests provide immediate feedback to the operator, so that the operator can adjust the earmuff or try to minimize room noise to advance the testing. Also, the measurements provide information that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of efforts to reduce noise over time. For example, in this study, the effect of the better fitting pediatric hearing protector could be clearly seen in the 1/3-octave band data.

This approach has limitations. The 1/3-octave band noise level data are collected prior to the actual threshold measurement, so the measurements don’t provide information on the noise environment during the measurement. Changes in ambient noise levels after the 1/3-octave band measurements are made, or movement of the earmuff subsequent to the in-ear noise assessment, can still affect the hearing threshold measurements. Additionally, the microphone used to make the measurements is not optimized for making very low-level measurements, and so the 1/3-octave band measurements obtained with it do not provide data similar to that provided from a high-quality sound-level meter.

Summary

In-ear 1/3-octave band measurements provide a way to perform threshold-based hearing testing in field settings without using a sound booth. The measurements give the operator feedback on the testing environment, and can be used to adjust the earmuff and reduce ambient noise to create the quietest testing environment possible.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grant R01DC009972 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). We thank the team at the DarDar clinic in Dar es Salaam ,Tanzania who collected these data (Esther Kayichile, Kissa Albert, Safina Sheshe, Claudia Gasana, Mariane Mpessa, and Joyce Joseph). We also appreciate the support from audiologists Machemba Lawrence and Alfred Mathayo. We thank the team at Creare, Inc. that assembled and tested the hearing testing systems, particularly Jed Wilbur and Nathan Brown. We appreciate the support of Erika Kafwimi and Sabrina Yegela who helped with building the video questionnaire and translating the questions.

Footnotes

Some of these data were presented at the 3rd Coalition for Global Hearing Health Conference in Pretoria, South Africa.

References

- American_National_Standard. Maximum Permissible Ambient Noise Levels for Audiometric Test Rooms. New York, New York: Secretariat, Acoustical Society of America; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American_National_Standard. Specification for Audiometers. Melville, NH: 2004. [Secretariat, Acoustical Society of America]. [Google Scholar]

- American_National_Standard. Specification for Octave-Band and Fractional-Octave- Band Analog and Digital Filters. Melville, NH: Secretariat, Acoustical Society of America; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maclennan-Smith F, Swanepoel de W, Hall JW., 3rd Validity of diagnostic puretone audiometry without a sound-treated environment in older adults. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:66–73. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2012.736692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JE, Jastrzembski BG, Buckey JC, Enriquez D, Mackenzie TA, et al. Hearing Loss and Heavy Metal Toxicity in a Nicaraguan Mining Community: Audiological Results and Case Reports. Audiology & neuro-otology. 2012;18:101–113. doi: 10.1159/000345470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanepoel de W, Koekemoer D, Clark J. Intercontinental hearing assessment - a study in tele-audiology. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2010;16:248–252. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.090906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]