Abstract

Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) catalyzes the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides to provide the monomeric building blocks for DNA replication and repair. Nucleotide reduction occurs by way of multi-step proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) over a pathway of redox active amino acids spanning ~ 35 Å and two subunits (α2 and β2). Despite the fact that PCET in RNR is rapid, slow conformational changes mask kinetic examination of these steps. As such, we have pioneered methodology in which site-specific incorporation of a [ReI] photooxidant on the surface of the β2 subunit (photoβ2) allows photochemical oxidation of the adjacent PCET pathway residue β-Y356 and time-resolved spectroscopic observation of the ensuing reactivity. A series of photoβ2s capable of performing photoinitiated substrate turnover have been prepared in which four different fluorotyrosines (FnYs) are incorporated in place of β-Y356. The FnYs are deprotonated under biological conditions, undergo oxidation by electron transfer (ET) and provide a means by which to vary the ET driving force (ΔG°) with minimal additional perturbations across the series. We have used these features to map the correlation between ΔG° and kET both with and without the fully assembled photoRNR complex. The photooxidation of FnY356 within the α/β subunit interface occurs within the Marcus inverted region with a reorganization energy of λ ≈ 1 eV. We also observe enhanced electronic coupling between donor and acceptor (HDA) in the presence of an intact PCET pathway. Additionally, we have investigated the dynamics of proton transfer (PT) by a variety of methods including dependencies on solvent isotopic composition, buffer concentration, and pH. We present evidence for the role of α2 in facilitating PT during β-Y356 photooxidation; PT occurs by way of readily exchangeable positions and within a relatively “tight” subunit interface. These findings show that RNR controls ET by lowering λ, raising HDA, and directing PT both within and between individual polypeptide subunits.

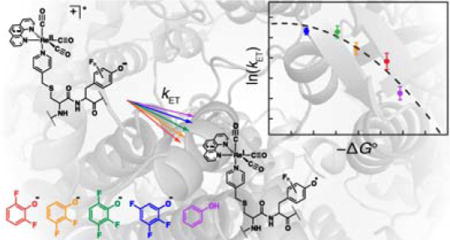

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Enzymatic electron transfer (ET) plays a central role in biological energy transduction.1 Catalytic cofactors face the formidable challenge of maintaining control over highly reactive species within the milieu of the protein scaffold. This feat is particularly remarkable when ET processes involve the formation of amino acid radical intermediates, the reversibility of which is dictated by the surrounding environment.2 Such events are usually coupled to the transfer of a proton via proton-coupled ET (PCET).3–7 The coordination of proton and electron is critical to the function of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), whose catalytic ability to convert ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides relies on reversible long-range PCET spanning two subunits and ~35 Å (Figure 1).8 The active form of the class Ia RNR from E. coli is composed of two obligate homodimers, α2 and β2 (Figure 1)9–13. The α2 subunit contains the active site, as well as additional binding sites for allosteric effectors that control both overall activity, and substrate specificity. The β2 subunit contains the diferric–tyrosyl radical cofactor, FeIII2(μ−O)/Y•, responsible for initiating active site chemistry. Translocation of this stable radical in the β2 subunit, to the active site in the α2 subunit occurs by way of multi-site PCET hopping over a pathway of redox active amino acids.8,14 The RNR mechanism begins with substrate binding in α2,15,16 which triggers a conformational change resulting in proton transfer from a water molecule ligated to the differic co-factor to the stable β-Y122•.17 Simultaneous ET results in oxidation of β-Y356,16,18 exemplifying orthogonal, or bidirectional PCET. From here, PCET across the subunit interface sequentially oxidizes α-Y731, α-Y730,19,20 and then α-C439 (Figure 1 inset), via collinear PCET21 (in which protons and electrons are mutually exchanged between the same donor and acceptor partners). Upon oxidation, α-C439• initiates active site chemistry by hydrogen atom abstraction from substrate.22–24 Multi-step substrate-based radical chemistry follows,25,26 after which reverse PCET carries the radical “hole” back to its stable resting state at Y122 in β via the same PCET pathway.27

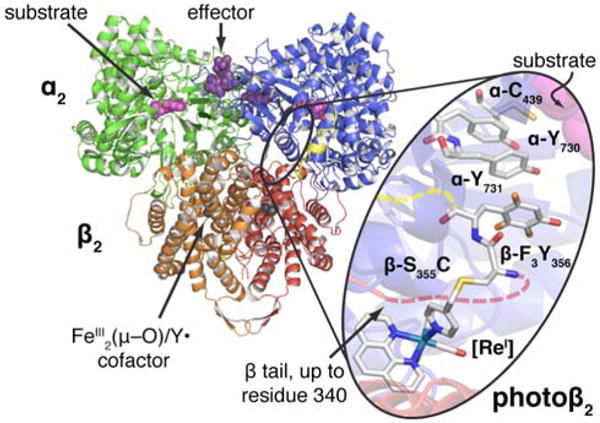

Figure 1.

Docking model of the active E. coli class Ia RNR, an α2β2 complex. α2 (blue and green) co-crystalizes with a peptide corresponding to the 15 C-terminal residues of β (yellow) (ref 35). β2 crystallizes up to residue 340 (red and orange) (ref 36). Photoβ2s are prepared via cysteine ligation of a [ReI] complex at position 355, and incorporation of a fluorotyrosine at position 356 (inset). Due to the absence of structural information for residues 341–359 of β, attachment of the [ReI]-S355C-F3Y356 fragment is illustrated by dashed lines (red leading from the crystalline β subunit, yellow leading to the C-terminal peptide bound to α).

To measure the kinetics of PCET events in RNR, we have developed phototriggering methods to bypass rate-determining conformational changes.28 This methodology has enabled detailed studies of photoinitiated substrate turnover,29 spectroscopic observation of photogenerated radicals,30 and measurement of both radical injection rates into α2,31 and radical propagation rates through α2 to the active site.24 A photochemically competent β2 subunit32 (photoβ2) is prepared by installing three mutations (C268S, C305S, and S355C) to render a single cysteine residue surface-exposed, and facilitate site-specific conjugation of a bromomethylpyridyl rhenium(I) tricarbonyl phenanthroline complex ([ReI]) to position β355 via an SN2 reaction.33 Recently, we extended this methodology by incorporating 2,3,5-F3Y at position β356 via nonsense codon suppression methodology (Figure 1, inset).34 This allowed direct observation of photogenerated radicals by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy and elucidation of the kinetics for radical propagation steps through α.24

Little is known about the structure and dynamics occurring at the RNR subunit interface. Not only is a complete crystal structure of the α2β2 complex absent,35 but structures of the β2 and α2 subunits alone all lack structural information regarding the key redox active residue β-Y356.36 Herein, we unveil new aspects of the molecular and intermolecular interactions governing charge transfer within the RNR subunit interface by modulating the driving force through incorporation of unnatural amino acid fluorotyrosines (FnYs), whose unique electrochemical and acid/base properties allow systematic correlation of kET and ΔG°, as well as dependencies on pH, buffer concentration, and solvent isotopic composition. A series of photoβ2s have been prepared in which four different FnYs (n = 2−3) are incorporated at position β356. Each of these photoβ2s is capable of photochemical substrate turnover, and they demonstrate reactivity that depends on the oligomeric state (dictated by allosteric effectors), highlighting an allegiance to wt-RNR chemistry. The FnYs used here display a range of reduction potentials (Figure 2),37 yet incur only small perturbations relative to each other across the series. These features, coupled with the fact that FnYs can exist in their deprotonated forms under biologically compatible conditions, render the series of photoβ2s ideally suited for examination of the relationship between kET and ΔG° within the unique dielectric environment of a protein/protein interface.38

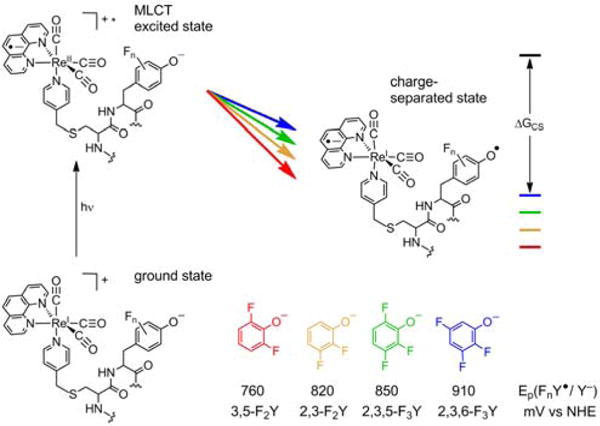

Figure 2.

Photooxidation of β-FnY356 by the metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) excited state of [ReI]*. Variation of the driving force for this process is achieved by incorporation of various FnYs at position β356. Peak potentials are taken from differential pulse voltammetry performed on the N-acetyl C-amide-protected amino acid derivatives.37

By examining the relationship between kET and ΔG°, we have found that the photooxidation of FnY356 occurs within the Marcus inverted region. From the Marcus curve, we estimate that λ ≈ 1 eV within the α/β subunit interface, and that the presence of an intact PCET pathway increases the electronic coupling between donor and acceptor. Through this work we have uncovered a distinct role of the α2 subunit in facilitating PT during β-Y356 oxidation. We have further elaborated our studies by examining the PCET kinetics as a function of pH, solvent isotopic constitution, and buffer concentration all as a function of oligomeric state and in the presence and absence of the next PCET pathway residue, α-Y731. Our data support a model for the PT pathway that exhibits tightly bound, yet solvent exchangeable protons that assist the intersubunit ET.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Wt-α2 (2,000 nmol/mg/min) was expressed from pET28a-nrdA and purified as previously described.19 A glycerol stock of Y731F-α2 was available from a previous study,31 and was expressed and purified as wt-α2. All α2 proteins were pre-reduced and treated with hydroxyurea (HU, Sigma Aldrich) by incubation with 30 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, Promega) for 30 min at room temperature, then addition of 15 mM more DTT and 15 mM HU, followed by buffer exchange on a Sephadex G-25 or G-50 column.18 [5-3H]-cytidine 5′-diphosphate sodium salt hydrate ([5-3H]-CDP) was purchased from ViTrax (Placentia, CA). 2,3,5-Trifluoroboronic acid, 2,3,6-trifluorophenol, 2,3-difluorophenol, and 3,5-difluorophenol were commercially available (Sigma Aldrich). Tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline)(4-bromomethyl-pyridine)rhenium(I) hexafluorophosphate ([ReI]–Br) was available from a previous study.33 E. coli thioredoxin (TR, 40 μmol/min/mg) and thioredoxin reductase (TRR, 1,800 μmol/min/mg) were prepared as previously described.39,40 Flurotyrosines were synthesized enzymatically from pyruvate, ammonia, and the corresponding fluorophenol with tyrosine phenol lyase as previously described.41 Assay buffer consists of 50 mM HEPES, 15 mM MgSO4, and 1 mM EDTA adjusted to the specified pH.

2,3,5-Trifluorophenol was synthesized according to published procedures for related fluorophenols as summarized briefly below.42 1.2 equiv H2O2 (34 mmol; 3.9 mL of a 30% v/v solution) was added to a stirring slurry of 5.00 g (28.4 mmol) 2,3,5-trifluorophenylboronic acid in 100 mL water. The reaction was allowed to stir overnight at room temperature during which time the insoluble starting material is converted to the soluble product. Addition of 100 mL 1 M HCl was followed by extraction twice into 100 mL CH2Cl2 and solvent removal in vacuo. The product was collected in 85% yield. TLC (4:1 Hexanes: EtOAc) Rf = 0.45. 1HNMR 19F NMR chemical shift match previously reported spectra.37

Photoβ2s were prepared as previously described24 with yields listed in Table S1. Assessment of Y122• content was performed by the dropline method43 and enzymatic activity was (Table S1) assessed as previously described,43 briefly outlined in the SI. Assessment of purity was performed by 10% SDS-PAGE (Figure S1). Labeling with [Re]-Br was performed as previously described32 by addition of a small volume of 5 equiv [Re]-Br in DMF to protein that has been reduced with DTT and buffer exchanged into 50 mM Tris, 5% glycerol at pH 8.0. Incubation at room tempertaure for 2 h was followed by buffer exchange via Sephadex G-25 size exclusion chromatography. Addition of 30 mM hydroxyurea (HU) to reduce Y122• and incubation at room temperture for 30 min preceded a final round of buffer exchange into assay buffer.

Photochemical single turnover experiments were performed as previously described.24,28,33,46 Additional controls for the observed photochemical reactivity of photoβ2s were examined in conjunction with Y731F-α2 and [Re]-Y356F-β2 are presented in Figure S2.

pKa titrations were performed as previously described.24 Samples contained 5 μM photoβ2, 20 μM wt-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in 15 mM MgSO4 and 1 mM EDTA and 50 mM of one of the following: MES: pH 5.4 – 6.8; HEPES: pH 6.8 – 8.0; TAPS: pH 8.2 – 9.0. Measurements were performed in a 0.4 cm quartz cuvette held at 25 °C with λexc = 315 nm and emission detected over 450–650 nm in conjunction with a 420 nm long-pass cutoff filter.

Nanosecond laser flash photolysis was performed with a system that has previously been described.31 Optical long-pass cutoff filters (λ > 375 nm) were used before detection to remove scattered 355 nm pump light. Slit widths corresponding to ± 1 nm resolution were used and the laser power set to 2 mJ/pulse. All transient spectroscopy samples were prepared in a 500 μL volume containing 10 μM photoβ2, 25 μM α2 (or variant), 1 mM CDP and 3 mM ATP or 200 μM dATP in assay buffer. Samples were recirculated through a peristaltic pump to attenuate sample decay. Each measurement is an average over 1000 laser shots and was performed in triplicate on independently prepared samples, with the exception of pH dependence data, in which measurements were performed only in duplicate.

Analysis of kinetics data was performed by fitting each emission decay trace to Eq. 1 over the span of 0.1–4.5 μs using OriginPro 8.0 software (OriginLab). Acceptability of fitting was determined on the basis of qualitative symmetry of residuals about zero amplitude and the R2 factor. Exemplary traces and residuals are available in Figure S3.

| (1) |

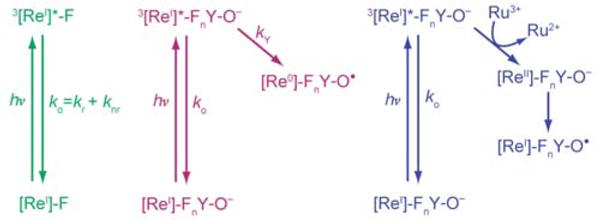

Under each experimental condition two sets of lifetime (τ) data were obtained in order to calculate kET or kPCET. These two τ values correspond to the [ReI]* lifetime measured (under each experimental condition) with the photoβ2 containing F at position β356 (τo, green in Scheme 1) and with the photoβ2 containing Y or FnY at position β356 (τY, purple in Scheme 1). Plugging these numbers into Eq. 2 then yields the rate constant for the relevant pathway of [ReI]* quenching, namely Y or FnY oxidation.

| (2) |

Scheme 1.

Photochemical generation of FnY•

The absolute uncertainty of each k(PC)ET (δ) was calculated according to Eq. 3 below, where σ represents one standard deviation among each set of lifetime data (τ). As a result of high S/N in these experiments, the error associated with the fitting process was consistently close to three orders of magnitude smaller than the lifetime value itself. As such, this error was insignificant relative to the standard deviation between replicates.

| (3) |

Dependence of kPCET on oligomeric state was ascertained by conducting emission quenching experiments as outlined above in assay buffer (15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.6) containing either 1 mM CDP and 3 mM ATP to promote the active α2β2 oligomer, or 200 μM dATP to promote the inactive α4β4 oligomeric state.

Solvent isotope effect samples were prepared by lyophilizing 4× concentrations of assay buffer followed by rehydration in D2O. The buffer pL was adjusted to 7.6 for all samples by addition of NaOD or NaOH according to Eq. 4.44

| (4) |

All protein samples used were exchanged into [2H]-assay buffer by 5 cycles of 5-fold concentration followed by resuspension using pre-soaked 30 kDa MWCO centrifugal filters (Millipore) to ensure that <3% H2O remained in D2O samples. Samples prepared in [1H]-assay buffer were treated identically to ensure that any effect of this treatment was identical for all samples under study.

pH dependence of k(PC)ET was performed by measuring emission lifetimes as outlined above with samples containing 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer containing 50 mM of one of the following: MES: pH 5.4–6.8; HEPES: pH 6.8–8.0; TAPS: pH 8.2–9.0, adjusted to the appropriate pH. In these experiments the emission is quenched much more rapidly (where the forward and reverse rates occur simultaneously to set up an equilibrium) when FnY is deprotonated, thus revealing the pKa by a sharp reduction in the total emission intensity.

RESULTS

In order to assess the influence of the protein environment on ET kinetics, a series of phtotoβ2s were prepared in which four different FnYs (Figure 2) are incorporated at position β356. In this way, the driving force for electron transfer from FnY− to [ReI]* was varied over ~150 mV while incurring minimal additional perturbations across the series. The dissociation constant for photoβ2 binding to α2 is 0.7 ± 0.1 μM.33 This value reveals that incorporation of the [ReI] complex incurs only a small disruption to the subunit interaction, as the Kd for wt-RNR is 0.2 μM.45 Of the six photoβ2s under study, only that with 3,5-F2Y displayed native enzymatic activity in its holo-state (still containing the Y122• cofactor, prior to reduction with HU). The specific activities measured before and after labeling with [ReI] were 1000 and 300 nmol(min-mg)−1, respectively for this photoβ2 (Table S1). For reference wt-β2 has specific activity of 6000 nmol(min-mg)−1. The photoβ2 with Y at position 356 exhibits specific activities of 2300 and 200 nmol(min-mg)−1, before and after labeling with [ReI], respectively. In both of these cases (3,5-F2Y and Y), the activity prior to labeling exhibits nonlinear behavior due to the oxidation of S355C. The activity is linear after labeling with [ReI] because the thiol is converted to a thioether, which is more difficult to oxidize. The fact that Y and 3,5-F2Y are the easiest Y-derivatives in the series to oxidize coincides with the fact that these are the only two photoβ2s exhibiting non-photochemical activity.

Photochemical turnover

We sought to confirm that these photoβ2s are photochemically competent for turnover. To this end, we performed single turnover experiments under white light illumination in the presence of radiolabelled substrate (Figure 3). We note that in all cases the native Y122• cofactor within the photoβ2s has been quantitatively reduced by treatment with HU, rendering them incapable of undergoing turnover via the non-photochemical mechanism. Residual reactivity can be seen in the amount of turnover observed in the dark (green bars, Figure 3). Similarly, control experiments with variants containing redox-inactive pathway substitutions exhibit very low background levels of product formation under illumination (Figure S2).

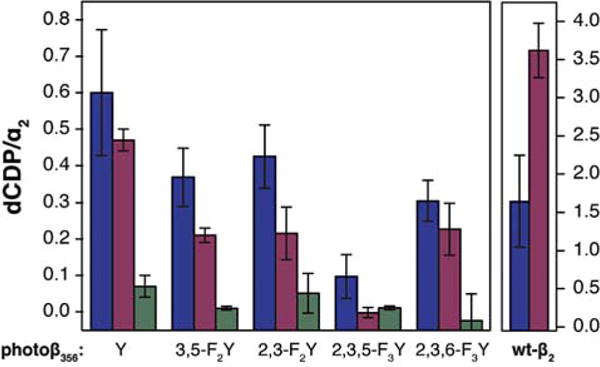

Figure 3.

Photochemical single turnover experiments in the presence (blue) and absence (purple) of 10 mM Ru(NH3)6Cl3. Control experiments (green) were performed in the dark. Samples contained 10 μM (blue) or 20 μM (purple and green) of photo- or wt-β2 as indicated along the x-axis, 10 μM wt-α2, 200 μM [5-3H]-CDP with 27,000 cpm/nmol radioactivity, 3 mM ATP, in assay buffer at pH 7.6. Error bars represent 1 s.d. for 3 independent trials.

Two methods for the photochemical generation of FnY• have been implemented in this work. In the direct method, (Scheme 1, purple) the excited state 3[ReI]* complex oxidizes the adjacent Y-derivative directly.28,33,44,46 A second method, utilizes flash-quench methodology where, in the presence of excess Ru(NH3)6Cl3, the excited state 3[ReI]* is oxidized via bimolecular reaction with Ru(NH3)63+, yielding Ru(NH3)62+ and [ReII]. This [ReII] species then oxidizes FnY (Scheme 1, blue).24 These two photochemical generation methods were implemented under single turnover conditions for all photoβ2s. Wt-RNR can generate a theoretical maximum of 4 dCDP products per α2 subunit, one for each α monomer, and a second per monomer arising from the re-reduction of active site cysteines (α-C225 and C462) by disulfide exchange with two C–terminal cysteines (α-C754 and C759); this maximum is diminished for wt-β2 under flash-quench conditions (Figure 3, right). Notwithstanding, all photoβ2s exhibited the ability to produce products via photochemical activation (Figure 3), lending confidence that our method retains authenticity to RNR.

Oligomeric state

RNR exists naturally as a dimer, but can enter a complex equilibria involving oligomeric forms (α2, β2, α2β2, and α4β4) as dictated in vivo by the presence of allosteric effectors and substrates.9,47 The formation of an inhibited complex, the α4β4 oligomeric state, occurs at the high protein concentrations often required for in vitro biophysical measurements.48 Because the total protein concentration (35 μM) of our spectroscopic experiments may engender the inactive α4β4 state, we needed to establish the presence of α2β2 dimer in our experiments. The inhibited α4β4 state is favored for dATP concentrations >100 μM, whereas the active form is known to exist (at least transiently) in the case where ATP and CDP are present.9 We used these facts to investigate which oligomeric state(s) predominate under our experimental conditions. Under the conditions of ATP and CDP, we observe a 34% enhancement in kPCET (with the photoβ2 containing Y at position 356) in the presence of wt-α2 relative to Y731F-α2 (Table 1). We have previously ascribed this enhancement to a dependence on the presence of an intact PCET pathway.33 On the contrary, in the presence of 200 μM dATP (promoting the α4β4 state), identical kPCET values were obtained in the presence of wt-α2 and Y731F-α2 (Table 1). These results are consistent with the structure of the α4β4 oligomer, which unlike the globular form of the active α2β2 complex, forms a donut-shaped oligomer.48 The C-termini of β2 remain bound to α2 in this state, giving rise to exposure of Y356 to bulk solution. Thus Y731 of the α2 subunit is not adjacent to Y356 in the α4β4 oligomer and the PCET pathway from β2 to the neighboring α2 subunit is disrupted. Hence the photooxidation of Y356 within the inhibited oligomeric form should be unaffected by the presence or absence of α-Y731; the data in Table 1 show this to be the case. The results of Table 1 therefore establish that the photoβ2α2 state exists under normal experimental conditions in which CDP and ATP are present and that we are examining photooxidation events within the subunit interface of the active α2β2 complex.

Table 1.

Dependence of kPCET on oligomeric state

| Effector | Interface Residues

|

τa (ns) | kPCETb (105 s−1) | Pathway Enhancement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β356 | α731 | ||||

| ATP | Y | Y | 522 (8) | 4.8 (3) | 34(6)% |

| F | Y | 696 (3) | |||

| Y | F | 578 (9) | 3.6 (3) | ||

| F | F | 728 (5) | |||

|

| |||||

| dATP | Y | Y | 505 (10) | 5.5 (4) | statistically identical |

| F | Y | 698 (2) | |||

| Y | F | 511 (14) | 5.3 (6) | ||

| F | F | 699 (8) | |||

Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM Y356- or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt- or Y731F-α2, and either 1 mM CDP with 3 mM ATP or 0.2 mM dATP, in assay buffer at pH 7.6.

Calculated according to Eq. 2.

Energetics

The overall free energy change accompanying the generation of the photoβ2 charge-separated state is schematically represented in Figure 2 and given by,

| (5) |

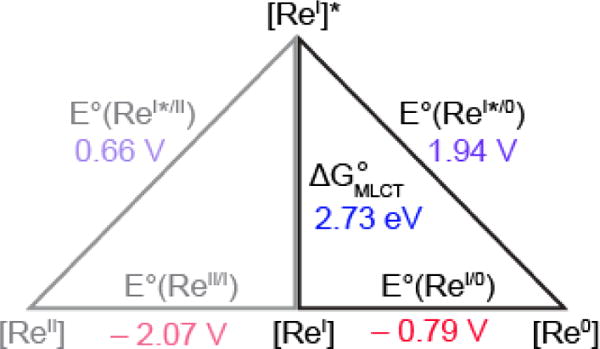

[ReI] and FnY− initially have equal and opposite charges that are neutralized upon ET; the additional contribution to ΔG° from an electrostatic work term is negligible. The excited state emission energy was determined from the low temperature (77 K) emission spectrum of [Re]-Y356F-β2 as previously described49 to yield ΔGMLCT of 2.73 eV (Figure S4). A shift in this value is not observed when the measurement is performed in the presence of the α2 subunit. The ground state reduction potential of [ReI(phen)(CO)3EtPy]-PF6 has previously been reported to be −0.79 V vs NHE.50 As summarized on the Latimer diagram of Figure 4, from these values, the excited state reduction potential is calculated to be E°([ReI]*/[Re0]) = 1.94 V vs NHE.

Figure 4.

Latimer diagram describing excited state reduction potentials of [ReI]. ΔGMLCT determined from the E0/0 emission of [Re]-Y356F-β2 frozen in assay buffer at 77 K (Figure S4). Ground state reduction potentials are from ref 50. Values along the diagonal are the calculated excited state reduction potentials.

The FnY reduction potentials were measured by differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with the N-acetyl C-amide protected amino acid derivatives (Figure S5).37 The propensity of tyrosine to undergo fast bimolecular chemical reactions following its one-electron oxidation has precluded accurate determination of the thermodynamic (reversible) reduction potentials. However, evidence from de novo protein model systems in which redox active amino acids are sequestered from solution,51 the reversible reduction potentials for both Y and 3,5-F2Y have been determined.52 In each case, the absolute values of E°′ differ by ~150 mV from those determined by DPV. However, the relative potentials of Y and 3,5-F2Y (ΔE°′ = 30 mV at pH 5.7), remain very close to the relative potentials measured by DPV (ΔEp = 50 mV, pH 5.7).37 Thus, in the current work we apply the assumption that all FnYs within the subunit interface will be subject to similar perturbations, prompting the caveat that all ΔG°s may be shifted and that values are to be interpreted as relative rather than absolute. We note that rapid freeze quench electron paramagnetic resonance (RFQ-EPR) spectroscopy of radical equilibration along the PCET pathway reveals that β-Y356 is about 100 mV easier to oxidize than the adjacent α-Y731 residue20 but we have not included any correction factors in our calculations of ΔG° herein and simply reiterate the aforementioned caveat.

The pKas of the FnYs within the photoβ2α2 complex (Table 2) are obtained by measuring the intensity of steady-state [ReI]* emission as a function of pH. Figure 5 shows the normalized integrated emission intensity (I) as a function of pH. The pKa is afforded from fitting these data to the following,

| (6) |

Table 2.

pKa values of FnYs within the photoRNR complex

Figure 5.

Steady state emission titrations of FnY356 within photoβ2α2 complexes are plotted as normalized integrated emission intensity measured over 450–650 nm for 2,3,5-F3Y356 (

); 3,5-F2Y356 (

); 3,5-F2Y356 (

); 2,3,6-F3Y356 (

); 2,3,6-F3Y356 (

); 2,3-F2Y356 (

); 2,3-F2Y356 (

) and fit to Eq. 6 (lines). Samples contained 5 μM photoβ2, 20 μM wt-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP, in assay buffers described in the Methods section, held at 25 °C. The solid lines are the result of fitting the data to Eq. 6.

) and fit to Eq. 6 (lines). Samples contained 5 μM photoβ2, 20 μM wt-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP, in assay buffers described in the Methods section, held at 25 °C. The solid lines are the result of fitting the data to Eq. 6.

Only slight differences are found between the pKas for FnYs in the protein and the corresponding N-acetyl C-amide protected FnYs. As previously observed for RNR,53 there is little perturbation to the phenolic pKas at position β356 within the complex.

Based on these data, experiments to examine the kinetics of ET for the photoβ2s were conducted at pH 8.2 such that the FnYs are nearly fully deprotonated. Accordingly, the reduction potentials to be used in Eq. 5 were taken from the pH-independent regions of DPV Pourbaix diagrams (Figure S5). For the cases of Y and 2,3-F2Y (which is only ~80% deprotonated at pH 8.2), the Nernst equation (Eq. 7) was applied to calculate the reduction potentials under the experimental conditions.

| (7) |

With the excited stated reduction potential of 3[ReI]* and each FnY− in hand, the driving force for photogeneration of each charge-separated state may be determined from Eq. 5.

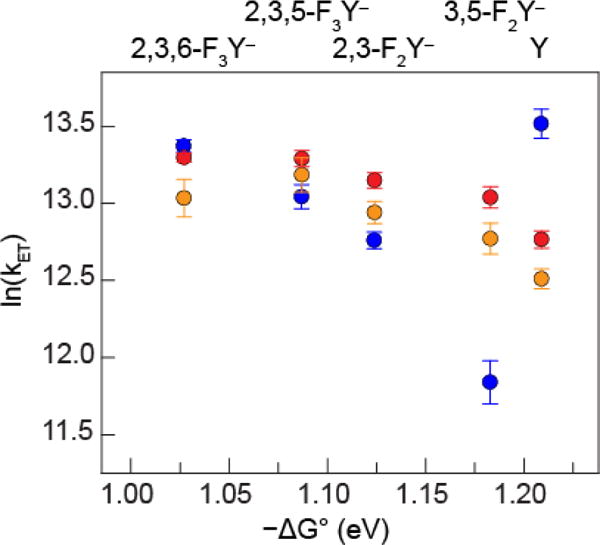

Electron Transfer Kinetics

The excited state lifetime of 3[ReI]* (τ) for each photoβ2 was measured by nanosecond laser flash photolysis (in the absence of flash quencher). The rate constant for the formation of the charge-separated state resulting from 3[ReI]* reduction via FnY oxidation may be determined from Eq. 2, where τ for photoβ2s containing Y or FnY at position β356 is referenced to τo for Y356F-photoβ2 (purple versus green in Scheme 1). In this way, all pathways for 3[ReI]* decay besides that proceeding via FnY oxidation are accounted for and kET represents the rate constant of only the relevant reaction. The rate constants summarized in Figure 6 were determined from measurements in triplicate for each photoβ2 alone, in the presence of wt-α2, and in the presence of Y731F-α2. The latter experiment was performed as a control wherein the α2β2 complex is intact but charge injection into α2 is prevented; thus it is a measure of the decay of the photogenerated radical within the β2 subunit of a fully assembled system. Experiments with α2 variants were conducted at protein concentrations such that >95% of the photoβ2 moiety was in complex with α2, based on the Kd measured for photoβ2α2 dissociation of 0.7 ± 0.1 μM.33 All samples contained saturating concentrations of substrate (CDP) and effector (ATP) in order to ensure binding in an active conformer (Table 1). A detailed account of our interpretation and analysis of these data is included in the Discussion section, wherein the data are replotted and overlaid with simulations of the semiclassical Marcus relation (Eq. 9).

Figure 6.

Correlation of the natural log of kET and ΔG° for photoβ2s alone (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

). kET and ΔG° were calculated according to Eq.s 2 and 5, respectively. Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM FnY356-photoβ2 (n = 0–3) or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer at pH 8.2.

). kET and ΔG° were calculated according to Eq.s 2 and 5, respectively. Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM FnY356-photoβ2 (n = 0–3) or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer at pH 8.2.

The effects of solvent isotopic composition, buffer concentration, and pH, on the kinetics of charge transfer at the interface were examined, both in the presence and absence of α2 and the Y731F-α2 variant. We note that where Y, or a protonated FnY is positioned at β356 we have labeled the corresponding rate constants with kPCET rather than kET. Solvent kinetic isotope measurements (SKIE) of the photooxidation of Y356 occurs with SKIE ~1.5 under all three conditions listed in Table 3. Such isotope effects are observed54–56 and theoretically3,57 predicted when the PCET involves electron transfer through a hydrogen bond. This observation of a small isotope effect suggests that proton acceptor(s) reside in positions that are hydrogen bonded and are readily exchangeable with solvent. This holds both in the presence and absence of α2, and regardless of whether or not the PCET pathway is intact. Alternatively, a modest to negligible value may be the result of viscosity and/or pKa differences resulting from the different properties of the two buffers.

Table 3.

Solvent kinetic isotope effect on kPCET

| Interface residues | τ (ns)a | kPCET (105 s−1)b | SKIE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| β356 | α731 | 1H | 2H | 1H | 2H | |

| Y | – | 410 (20) | 568 (5) | 8 (1) | 5.5 (2) | 1.5 (2) |

| F | – | 615 (5) | 827 (9) | |||

| Y | Y | 522 (8) | 713 (3) | 4.8 (3) | 3.2 (1) | 1.4 (1) |

| F | Y | 696 (3) | 920 (2) | |||

| Y | F | 578 (9) | 778 (6) | 3.6 (3) | 2.4 (1) | 1.5 (1) |

| F | F | 728 (5) | 952 (8) | |||

Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM Y356 or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer at pL 7.6.

Calculated according to Eq. 2.

Figure 7 displays the results of the dependence of kPCET on buffer concentration. The effects are small when compared to similar studies performed with small molecule model systems in solution, in which kPCET may change by an order of magnitude over similar ranges of buffer concentration.58,59 Unlike studies with small molecules, we also find that a dependence on buffer concentration is manifest only at low concentrations. These data suggest that the subunit interface is relatively protected from solvent species. The dependence that we do observe is slightly larger in the presence of wt-α2 relative to Y731F-α2. This may implicate a role for α-Y731 in facilitating PT from β-Y356, although it has been shown that this residue does not interact directly with β-Y356.21

Figure 7.

Dependence of kPCET on buffer concentration for photoβ2s alone (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

). kPCET was calculated according to Eq. 2. Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM Y356- or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer containing 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 50, 100, 150, or 500 mM HEPES buffer adjusted to pH 7.6.

). kPCET was calculated according to Eq. 2. Triplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM Y356- or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer containing 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 50, 100, 150, or 500 mM HEPES buffer adjusted to pH 7.6.

To further probe the extent that the α2 subunit facilitates PT during photooxidation of β-Y356 (either by specific residues or by dictating conformation), the pH dependence of kPCET and kET below and above the phenolic pKa of 2,3-F2Y-photoβ2 was examined. This FnY was selected because it has a pKa of 7.8 (Figure 5, Table 2), in the middle of the pH range that is accessible for the class Ia RNR. Figure 8 summarizes the pH dependence of photooxidation of this residue with the photoβ2 alone, or in the presence of wt- or Y731F-α2. In the absence of α2, kPCET increases linearly with pH up to the phenolic pKa, after which a sharp break occurs. Conversely, in the presence of α2 continuous behavior is observed over the entire pH range examined. This result supports the contention that α2 facilitates PT during β-Y356 photooxidation.

Figure 8.

Dependence of k(PC)ET on pH for 2,3-F2Y-photoβ2 alone (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

). k(PC)ET was calculated according to Eq. 2. Duplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM 2,3-F2Y356-photoβ2 or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer.

). k(PC)ET was calculated according to Eq. 2. Duplicate sets of independently prepared samples contained 10 μM 2,3-F2Y356-photoβ2 or Y356F-photoβ2, 25 μM wt-α2 or Y731F-α2, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP in assay buffer.

DISCUSSION

RNR maintains control over long-range PCET events by way of well-choreographed conformational dynamics.13,15,17,60 Kinetics measurements suggest that the PCET pathway is finely tuned and that it is the target of the conformational gating. 24,31,33,61 Crystallographic elucidation of the active α2β2 structure, however, has not been achieved so the structural details of conformational gating and its relation to radical transport via PCET remain to be elucidated. Some structural insight is provided from shape and charge complementarity studies of the separately crystallized subunits,10 furnishing the so-called α2β2 docking model (Figure 1), as supported by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryoEM), small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS), and pulsed electron-electron double resonance (PELDOR) spectroscopy with metastable trapped states of the α2β2 complex.11–13 Nonetheless, the last 25–30 amino acids remain disordered in the available structures of the β2 subunit. It is this C-terminal tail of β, specifically the last 15 residues, that is largely responsible for binding interactions with the α2 subunit62 and importantly the structurally disordered portion includes the key redox-active Y356, which mediates charge transfer at the interface of the α2 and β2 subunits.

Owing to this disorder, the specific molecular interactions within the α2β2 subunit interface remain largely unknown. More generally, insights have emerged from high-field EPR and [2H]-electron nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) spectroscopies in which radicals are trapped en route to the active site by a genetically encoded NH2Y residue to furnish a spectroscopic handle for examining hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) interactions along the PCET pathway.63 This work has revealed strong collinear H-bonding between α-Y731 and α-Y730, and that no such strong and/or static H-bonding interactions exist at position Y356.21 However, large shifts in gx values for β-Y356 do persist, suggesting that the dielectric medium of the interface is strongly perturbed within the active complex despite the absence of distinct H-bonds.

To directly investigate charge (electron and proton) dynamics at the interface, we have examined radical formation at the β-Y356 position within the α2β2 subunit interface by using fluorinated tyrosines. These unnatural amino acids allow charge transfer to be examined over a sizable driving force range according to the Marcus relation,64

| (8) |

where the electronic coupling HAD exhibits an exponential dependence on the distance between donor and acceptor (r) relative to the van der Waals contact distance (ro),

| (9) |

kET is related to ΔG° via reorganization energy λ and electronic coupling matrix element HAD. For the homologous series of FnYs, λ and HAD may be assumed to be similar across the series and hence the correlation between ln(kET) and ΔG is straightforward. In this case, the parabolic relationship between ln(kET) and ΔG° predicts that an increase in ΔG° results in faster rates when λ > |−ΔG°| and slower rates when λ < |−ΔG°|, known as the Marcus inverted region.

For the study reported herein, over the pH regime examined, the FnYs are deprotonated and radical generation in β-FnY356 is consequently well described by a pure ET. As Figure 6 shows, kET decreases with increasing driving force, a clear signature of Marcus inverted behavior. Entry into the Marcus inverted regime is largely a result of the high excited state reduction potential of 3[ReI]* (1.94 V vs NHE).

Figure 9 shows a simulation of Eq. 8. The Marcus simulations were performed using a full range of possible distances (r = 4–16 Å, Table S2) accounting for all reasonable conformations of the [Re]−C−FnY fragment (Figure S6). Regardless of which value of r is selected, the relative ratios of HAD values under the different conditions remain the same (Table S2), facilitating qualitative comparisons to be made. The range of ΔG° spanned by the FnY-photoβ2s (~150 mV) did not permit accurate fitting of Eq. 8. As such, the dashed lines of Figures 9 and 10 represent simulations of Eq. 8. The parameters used in these simulations represent the best agreement with the measured values. The data in Figure 9 were simulated with λ = 0.98 eV, a value that is approximately half that found for model [Re]-FnY systems (λ = 1.9 eV38). The lower λ for the RNR complex indicates that the subunit interface has evolved to facilitate inter-protein charge transfer, shielding reactive radical intermediates from the bulk solvent by lowering λ, yet all without precluding the required concomitant PT (vide infra). This result is in line with the general observation that λ within the protein environments is depressed65 as a result of a combination of the constraints imposed on dipole motions due to their confinement within the polypeptide matrix, as well as the low dielectric permittivity within the protein.66–70 Conversely, ET across weakly bound protein-protein complexes, or involving solvent-exposed cofactors incur higher reorganization energy penalties.71–73

Figure 9.

Correlation of the natural ln(kET) with ΔG° for photoβ2 in the presence of wt-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

), or Y731F-α2 (

). Dashed lines represent simulations of Eq. 8 for β-FnY356s in the presence of wt-α2 (

). Dashed lines represent simulations of Eq. 8 for β-FnY356s in the presence of wt-α2 (

) and Y731F-α2 (

) and Y731F-α2 (

), with r = 12.5 Å, λ = 0.98 eV and HAD = 0.051 and 0.044 cm−1 in the presence of wt- and Y731F-α2, respectively.

), with r = 12.5 Å, λ = 0.98 eV and HAD = 0.051 and 0.044 cm−1 in the presence of wt- and Y731F-α2, respectively.

Figure 10.

Correlation of the ln(kET) with ΔG° for photoβ2 in the absence α2 (

). Dashed lines represent simulations of Eq. 8 for photoβ-FnY356 (

). Dashed lines represent simulations of Eq. 8 for photoβ-FnY356 (

) and photoβ-Y356 (

) and photoβ-Y356 (

) with λ = 0.74 eV and 0.90 eV (r = 12.5 Å, HAD = 0.083 cm−1), respectively.

) with λ = 0.74 eV and 0.90 eV (r = 12.5 Å, HAD = 0.083 cm−1), respectively.

We note that the curve in Figure 9 for β-FnY356 in the presence of wt-α2 is higher than that for β-FnY356 in the presence of Y731F-α2 indicating greater electronic coupling for charge transfer in the former complex. The simulation of data for the β-FnY356:wt-α2 complex furnished HAD = 0.051 cm−1 vs. HAD = 0.044 cm−1 for the β-FnY356:Y731F-α2 complex. This result is consistent with our previous results that show charge transfer is facilitated by delocalization of the radical over the Y731-Y730 dyad of α2. When the Y-Y dyad is disrupted by a Y → F substitution in α2, radical propagation by charge transfer is attenuated.31,74 Accordingly, we ascribe the higher HAD in the wt complex to delocalization of the hole across the adjacent Y731 residue, a process that is precluded when Y731F is present. From the work of Beratan et al.,75 the amplitude of HAD2 determined from our data (4 × 10−11 eV2) falls within a regime that implicates an ordered network of water molecules and H-bonding interactions within the subunit interface. This result is in line with the small SKIE (Table 3) that we observe, further supporting the presence of water molecules within the α/β interface that facilitate rapid proton exchange at β-Y356. The presence of a network of water molecules is also consistent with the lack of observed signals for strong and static H-bonds at position Y356 by ENDOR spectroscopy.21

In the case of Y, tyrosine largely resides in its protonated state at pH 8.2. However, within the α2β2 complex, the protonated β-Y356 follows the trend of the deprotonated β-FnY356s. The rate constant for the former is smallest, as the system exhibits the largest driving force and hence falls deepest into the inverted region. In contrast, when uncomplexed, the protonated β-Y356 exhibits anomalous behavior from the deprotonated FnYs. Because charge transfer is occurring in the inverted region, the faster rate for the photoβ-Y356 implies a greater activation barrier for charge transfer. Indeed a simulation of the ET reaction of the photoβ-FnY356 yields λ = 0.74 eV whereas for photoβ-Y356 a value of λ = 0.90 eV is obtained (Figure 10). This simulated curve is presented only to illustrate the graphical repercussions of changing only the value of λ in the simulated curve and does not represent robust support. The difference of 160 mV is entirely consistent with the requirement of PT accompanying ET for the oxidation of tyrosine.

Calculations comparing reorganization energies for concerted PCET versus stepwise ET/PT charge transfer mechanisms in model systems find differences in λ of 134 mV;76 moreover experimental studies show that the PCET versus ET pathways in model systems incurs higher reorganization energies of 60–500 mV.77–79 The data in Figures 7 and 8 are also consistent with tyrosine oxidation by PCET in photoβ-Y356. Exposed to solution, the rate of reaction is accelerated by the presence of buffer (Figure 7), which provides a facile acceptor for the proton in the PCET reaction. Moreover, pH dependence of the rate of 2,3-F3Y oxidation in the 2,3-F2Y-photoβ shows a discontinuity at the pKa of the 2,3-F2Y (Figure 8), also consistent with a PCET process. It is noteworthy that the PCET kinetics are accelerated when the PCET pathway is fully assembled within an α2β2 complex. Whether via organization of the C-terminal tail of β, or through specific interactions with amino acid residues in α, or both, the PCET process for Y oxidation in the presence of α2 appears to behave kinetically like an ET process. These data highlight the exquisite control that RNR maintains over reactivity, engendered in part by managing PCET at the protein interface.

CONCLUSION

Radical transport in RNR occurs across two subunits along a PCET pathway that is emerging as the target of conformational gating within the enzyme. A critical step along the PCET pathway occurs at the subunit interface where PCET is proposed to transitions from a bidirectional to a collinear PCET pathway.4,8 To probe charge transport among the critical amino residues across the interface, we have introduced a series fluorotyrosines in photoβ2, thus allowing for the modulation of the free energy driving force and protonation state of residue β356. With this method, few additional perturbations between variants are incurred, allowing for the extraction of the energetics and electronic coupling of charge transport at the RNR interface. We have shown that each photoβ2 is photochemically competent and that rate constants for photoxidation depend on maintaining the active oligomeric state via the presence of allosteric effectors. Analysis of the correlation between kET and ΔG° reflects the ability of the protein to minimize the reorganization energy and increase electronic coupling at the protein-protein interface in the presence of the intact PCET pathway. Additionally, we present evidence that the α2 subunit facilitates PT from β-Y356, and that this process occurs via solvent exchangeable protons, within a tightly bound subunit interface. Our data add to mounting evidence that PCET through RNR is controlled by way of macromolecular conformational changes targeting the precise alignment of the PCET pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the NIH for funding (GM 47274 D.G.N., GM 29595 J.S.). L.O. acknowledges the NSF for a graduate fellowship.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental methods and instrumentation, expression, purification, radical yields and specific activities of photoβ2s, table of simulated Marcus parameters as a function of distance, SDS-PAGE purity gels for photoβ2s, additional controls for photochemical turnover experiments, exemplary emission decay traces, low temperature emission spectrum of Y356F-photoβ2, and differential pulse voltammetry data for N-acetyl C-amide protected FnYs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Winkler JR, Gray HB. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:537–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cukier RI, Nocera DG. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1998;49:337–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.49.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reece SY, Nocera DG. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:673–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.080207.092132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migliore A, Polizzi NF, Therien MJ, Beratan DN. Chem Rev. 2014;114:5832–3645. doi: 10.1021/cr4006654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg DR, Gagliardi CJ, Hull JF, Murphy CF, Kent CA, Westlake BC, Paul A, Ess DH, McCafferty DG, Meyer TJ. Chem Rev. 2012;112:4016–4093. doi: 10.1021/cr200177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammes-Schiffer S, Stuchebrukhov AA. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6939–6960. doi: 10.1021/cr1001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stubbe J, Nocera DG, Yee CS, Chang MCY. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2167–2202. doi: 10.1021/cr020421u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown NC, Reichard P. J Mol Biol. 1969:25–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhlin U, Eklund H. Nature. 1994;370:533–539. doi: 10.1038/370533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennati M, Robblee JH, Mugnaini V, Stubbe J, Freed JH, Borbat P. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15014–15015. doi: 10.1021/ja054991y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seyedsayamdost MR, Chan CTY, Mugnaini V, Stubbe J, Bennati M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15748–15749. doi: 10.1021/ja076459b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnihan EC, Ando N, Brignole EJ, Olshansky L, Chittuluru J, Asturias FJ, Drennan CL, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3835–3840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220691110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnihan EC, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:2524–2535. doi: 10.1021/ar4000407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge J, Yu G, Ator MA, Stubbe J. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10071–10083. doi: 10.1021/bi034374r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2522–2523. doi: 10.1021/ja057776q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wörsdörfer B, Conner DA, Yokoyama K, Livada J, Seyed-seyamdost MR, Jiang W, Silakov A, Stubbe J, Bollinger JMJr, Krebs C. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:8585–8593. doi: 10.1021/ja401342s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minnihan EC, Seyedsayamdost MR, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9430–9440. doi: 10.1021/ja201640n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seyedsayamdost MR, Xie J, Cham CTY, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15060–15071. doi: 10.1021/ja076043y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama K, Smith AA, Corzilius B, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18420–18432. doi: 10.1021/ja207455k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nick TU, Lee W, Koßmann S, Neese F, Stubbe J, Bennati M. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:289–298. doi: 10.1021/ja510513z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stubbe J, Ackles D. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:8027–8030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubbe J, Ator M, Krenitsky T. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:1625–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olshansky L, Pizano AA, Wei Y, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16210–16216. doi: 10.1021/ja507313w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stubbe J, van der Donk WA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:705–762. doi: 10.1021/cr9400875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Licht S, Stubbe J. Compr Nat Prod Chem. 1999;5:163–203. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2226–2227. doi: 10.1021/ja0685607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang MCY, Yee CS, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6882–6887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401718101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8500–8509. doi: 10.1021/ja0704434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13828–13830. doi: 10.1021/ja074452o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holder PG, Pizano AA, Anderson BL, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1172–1180. doi: 10.1021/ja209016j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizano AA, Lutterman DA, Holder PG, Teets TS, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:39–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115778108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pizano AA, Olshansky L, Holder PG, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13250–13253. doi: 10.1021/ja405498e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minnihan EC, Young DD, Schultz PG, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15942–15945. doi: 10.1021/ja207719f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eriksson M, Uhlin U, Ramaswamy S, Ekberg M, Regnström K, Sjöberg B-M, Eklund H. Structure. 1997;5:1077–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Högbom M, Galander M, Andersson M, Kolberg M, Hofbauer W, Lassmann G, Nordlund P, Lendzian F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3209–3214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536684100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seyedsayamdost MR, Reece SY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1569–1579. doi: 10.1021/ja055926r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reece SY, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13654–13655. doi: 10.1021/ja0636688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pigiet VP, Conley RR. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:6367–6372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lunn CA, Kathju S, Wallace BJ, Kushner SR, Pigiet V. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:10469–10474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H, Gollnick P, Phillips RS. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon J, Salzbrunn S, Prakash GKS, Petasis NA, Olah GA. J Org Chem. 2001;66:633–634. doi: 10.1021/jo0015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bollinger JM, Jr, Tong WH, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J. Meth Enzymol. 1995;258:278–303. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)58052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krężel A, Bal W. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Climent I, Sjöberg BM, Huang CY. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5164–5171. doi: 10.1021/bi00235a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reece SY, Lutterman DA, Seyedsayamdost MR, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5832–5838. doi: 10.1021/bi9005804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown NC, Reichard P. J Mol Biol. 1969:39–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ando N, Brignole EJ, Zimanyi CM, Funk MA, Yokoyama K, Asturias FJ, Stubbe J, Drennan CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:21046–21051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112715108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reece SY, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9448–9458. doi: 10.1021/ja0510360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kober EM, Caspar JV, Lumpkin RS, Meyer TJ. J Phys Chem. 1996;90:3722–3734. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berry BW, Martínez-Rivera MC, Tommos C. Procl Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9739–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112057109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravichandran KR, Liang L, Stubbe J, Tommos C. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8907–8915. doi: 10.1021/bi401494f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8385–8397. doi: 10.1021/ja101097p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turro C, Chang CK, Leroi GE, Cukier RI, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:4013–4015. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young ER, Rosenthal J, Hodgkiss JM, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7678–7684. doi: 10.1021/ja809777j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeRege PJF, Williams SA, Therien MJ. Science. 1995;269:1409–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.7660123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cukier RI. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:2377–2381. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irebo T, Reece SY, Sjödin M, Nocera DG, Hammarström L. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15462–15464. doi: 10.1021/ja073012u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonin J, Constentin C, Louault C, Robert M, Savéant J-M. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6668–6674. doi: 10.1021/ja110935c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Offenbacher AR, Watson RA, Pagba CV, Barry BA. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118:2993–3004. doi: 10.1021/jp501121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yokoyama K, Uhlin U, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15368–15379. doi: 10.1021/ja1069344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Climent I, Sjöberg BM, Huang CY. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4801–4807. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Argirević T, Riplinger C, Stubbe J, Neese F, Bennati M. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17661–17670. doi: 10.1021/ja3071682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcus RA, Sutin N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;811:265–322. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:537–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krishtalik LI. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1444–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meade TJ, Gray HB, Winkler JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4353–4356. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crane BR, Di Biolio AJ, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11623–11631. doi: 10.1021/ja0115870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McLendon G, Miller JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:7811–7816. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang N, Kuznetsov A, Nocek JM, Hoffman BM, Crane BR, Hu X, Beratan DN. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:9129–9141. doi: 10.1021/jp401551t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moser CC, Keske JM, Warnke K, Farid RS, Dutton LP. Nature. 1992;355:796–802. doi: 10.1038/355796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Co NP, Young RM, Smeigh AL, Wasielewski MR, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:12730–12736. doi: 10.1021/ja506388c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davidson VL. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:87–93. doi: 10.1021/ar9900616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song DY, Pizano AA, Holder PG, Stubbe J, Nocera DG. Chem Sci. 2015;6:4519–4524. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01125f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin J, Balabin IA, Beratan DN. Science. 2005;310:1311–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1118316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carra C, Iordanova N, Hammes-Schiffer S. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10429–10436. doi: 10.1021/ja035588z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Young ER, Rosenthal J, Nocera DG. Chem Commun. 2008:2322–2324. doi: 10.1039/b717747j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sjödin M, Irebo T, Utas JE, Lind J, Merényi G, Åkermark B, Hammarström L. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13076–13083. doi: 10.1021/ja063264f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Constentin C, Robert M, Savéant J-M. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;127:9953–9963. doi: 10.1021/ja071150d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.