Abstract

We examined how pathologists’ process their perceptions of how their interpretations on diagnoses for breast pathology cases agree with a reference standard. To accomplish this, we created an individualized self-directed continuing medical education program that showed pathologists interpreting breast specimens how their interpretations on a test set compared to a reference diagnosis developed by a consensus panel of experienced breast pathologists. After interpreting a test set of 60 cases, 92 participating pathologists were asked to estimate how their interpretations compared to the standard for benign without atypia, atypia, ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer. We then asked pathologists their thoughts about learning about differences in their perceptions compared to actual agreement. Overall, participants tended to overestimate their agreement with the reference standard, with a mean difference of 5.5% (75.9% actual agreement; 81.4% estimated agreement), especially for atypia and were least likely to overestimate it for invasive breast cancer. Non-academic affiliated pathologists were more likely to more closely estimate their performance relative to academic affiliated pathologists (77.6% versus 48%; p=0.001), whereas participants affiliated with an academic medical center were more likely to underestimate agreement with their diagnoses compared to non-academic affiliated pathologists (40% versus 6%). Prior to the continuing medical education program, nearly 55% (54.9%) of participants could not estimate whether they would over-interpret the cases or under-interpret them relative to the reference diagnosis. Nearly 80% (79.8%) reported learning new information from this individualized web-based continuing medical education program, and 23.9% of pathologists identified strategies they would change their practice to improve.

In conclusion, when evaluating breast pathology specimens, pathologists do a good job of estimating their diagnostic agreement with a reference standard, but for atypia cases, pathologists tend to overestimate diagnostic agreement. Many of these were able to identify ways to improve.

Introduction

In 2000, the 24 member Boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties, including the American Board of Pathology, agreed to evolve their recertification programs toward continuous professional development to ensure that physicians are committed to lifelong learning and competency in their specialty areas (1, 2). Measuring competencies occurs in a variety of ways according to specialty, which each Board determined in 2006 (1). One way competency measures are assessed by the Board is Practice Performance Assessment, which involves demonstrating use of best evidence and practices compared to peers and national benchmarks (1). All specialty boards are now in the process of implementing their respective Maintenance of Certification requirements.

To incentivize physicians to participate in new Maintenance of Certification activities, the Affordable Care Act (3) required the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to implement the Physician Quality Reporting System incentive program, which is a voluntary reporting program that provides an incentive payment to board certified physicians who acceptably report data on quality measures for Physician Fee Schedule covered services furnished to Medicare Part B Fee-for-Service recipients (4). The Physician Quality Reporting System represents a stunning change and likely an advancement in physicians’ professional development; namely, the opportunity for reporting of and reflection upon actual clinical practice activities. It is too early to tell what the above changes will mean for improvements in clinical care, or what the future holds in terms of required versus voluntary reporting of clinical care performance. However, there is much to be learned about how physicians process information about their clinical performance, which is directly relevant to Parts 2 and 3 of Maintenance of Certification, Lifelong Learning and Self- and Practice Performance Assessment (1).

Reviews on the effectiveness of continuing medical education indicate that for physicians to change their practice behaviors they must understand that a gap exists between their actual performance and what is considered optimal (5), which is not always immediately evident. Identifying an existing gap is the initial step, but understanding what might be causing the gap could assist physicians to identify strategies to improve their practice.

Interpretation of breast pathology is an area where significant diagnostic variation exists (6–8). We conducted a study with 92 pathologists across the U.S. that involved administering test sets of 60 breast pathology cases and comparing participants’ interpretations to a consensus reference diagnosis determined by a North American panel of experienced breast pathologists. We used the findings from the test set study to design an individualized educational intervention that identified the diagnostic agreement for four categories of breast pathology interpretations: benign without atypia, atypia (including atypical ductal hyperplasia and intraductal papilloma with atypia), ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer. In this paper, we report on: 1) breast pathologists’ estimates on how their estimated diagnostic interpretations compare to the reference diagnoses before they learned the actual reference diagnosis, 2) physician characteristics associated with under- and overestimates of diagnostic agreement with specialist consensus diagnosis, 3) the extent to which pathologists recognized the gap after the intervention, and 4) what pathologists reported they would change about their clinical practices. The approach we undertook to understand how pathologists process information about breast pathology cases has important implications for Maintenance of Certification activities in the field of pathology and for pathologist recognition of cases likely to have diagnostic disagreements.

Methods

IRB Approval and Test Set Development

All study activities were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant and were approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Washington, Dartmouth College, the University of Vermont, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Providence Health & Services of Oregon. A study-specific Certificate of Confidentiality was also obtained to protect the study findings from forced disclosure of identifiable information. Detailed information on the development of the test set is published elsewhere (9). Briefly, test set cases were identified from biopsy specimens obtained from mammography registries with linkages to breast pathology and/or tumor registries in Vermont and New Hampshire (10). Samples were chosen from cases biopsied between January 1st, 2000 and December 31st, 2007. A consensus process was undertaken by three experienced breast pathologists to come to a final reference diagnosis for each case in the test set, which is described elsewhere (12). Using a random stratified approach, patient cases were assigned into one of four test sets, which contained 60 cases each (240 total unique cases) and represented the following diagnostic categories: benign without atypia (30%), atypia (30%), ductal carcinoma in situ (30%) and invasive cancer (10%). This distribution resulted in an oversampling of more atypia and ductal carcinoma in situ cases, which would help quantify the diagnostic challenges to be included in the educational intervention.

Physician Recruitment and Survey

Pathologists were recruited to participate from eight geographically diverse states (AK, ME, MN, NM, NH, OR, WA, VT) via email, telephone, and street mail. All practicing pathologists in these states were invited to participate. To be eligible for participation, pathologists interpret breast biopsies as part of their practice, have been signing out breast biopsies for at least one year post residency or fellowship, and intend to continue interpreting breast biopsies for at least one year post enrollment. All participating physicians completed a brief 10-minute survey that assessed their demographic characteristics (age, sex), training and clinical experiences (fellowship, case load, interpretive volume, years interpreting, academic affiliations), and perceptions of how challenging breast pathology is to interpret. The survey was administered prior to beginning the test set interpretations. Two hundred and fifty-two pathologists of 389 eligible participants (65%) agreed to take part in the study. Among these, 126 were randomized to the current study (126 participants were offered participation in a related future study), 115 of these completed interpretation of test set cases and 94 completed the educational intervention upon which this study is based.

Educational Program Development and Implementation

The educational intervention was designed to provide a research-based review of differences among pathologists in breast tissue interpretation. It was a self-paced Internet hosted program individualized to participant’s interpretive performance on their respective test set. Before they reviewed how their interpretations compared to the reference diagnosis, we asked participants to compare how similar the test set cases were to cases they see in their practice (response options ranged from ‘I never see cases like these’ to ‘I always see cases like these’), and we asked them to indicate the number of continuing medical education hours they have undertaken in breast pathology interpretation over the past year as well as their continuing medical education preferences (instructor led, self-directed or other).

Lastly, at the beginning of the continuing medical education program, we asked participants to estimate, globally, how their interpretations would compare to the reference diagnosis (over interpret, under interpret, don’t know) and to estimate the proportion of their diagnoses on test cases they thought would agree with the reference diagnoses within each of the four diagnostic categories reviewed (benign, atypia, ductal carcinoma in situ, invasive). Participants’ estimates for each of the four categories were then assigned a weighted average using the proportion of their diagnoses they estimated agreed with the reference’ diagnoses and, as the weighting pattern, the number of cases each participant interpreted within each diagnostic class. Subtracting the weighted estimate of agreement with specialist consensus diagnoses from the participants’ actual agreement gave us the difference between perceived and actual agreement, or “perception gaps” to help identify potential performance gaps. We then categorized these differences for each of the four diagnostic categories according to three classifications: 1) those who were within one standard deviation of the mean (when compared to the reference diagnosis) were those who closely estimated their performance; 2) those whose estimates were more than one standard deviation above the mean were those who overestimated their agreement rates; and 3) those whose estimates were more than one standard deviation below the mean were those who underestimated their agreement rates.

The continuing medical education program then proceeded to show the pathologists, on a case-by-case basis, how their independent interpretations actually compared with both the reference diagnosis and with other participating pathologists. By clicking on the case number, participants could view a digital whole slide image of the case on their computer screens and could dynamically magnify and scan the image similar to a microscope (virtual digital microscope). Teaching points were provided for each case. Participants were given the opportunity to share their own thoughts on each case after seeing their results and reading the experienced pathologists’ teaching points. The intervention included an open text field that asked them what they would change in their clinical practice as a result of what they learned in this program. Lastly, a post-test asked study participants to again rate how their interpretations compared to the reference diagnosis, so we could assess the extent to which they recognized any areas of significant disagreement with reference diagnoses. We then asked them to complete required knowledge questions so that continuing medical education credits could be awarded. Completion of all study activities, including the test set interpretations and the continuing medical education program resulted in awarding up to 20 Category 1 continuing medical education hours (majority awarded 15–17 hours).

Data Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the demographic and clinical training experience as well as ratings of the test sets and challenges involved in interpreting breast pathology. Histograms were used to compare the pre-test differences between overall perceived and actual diagnostic agreement as well as agreement within each diagnostic group in both pre- and post-test settings. Among the 94 participants who completed the continuing medical education program, differences between perceived and actual performance rates could not be assigned to 2 participants (2.1%) due to missing responses. These two participants were excluded from analyses. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages and for continuous variables, values are reported as the mean and standard deviation. Cumulative logit models were fit to test the association between each participant characteristic and the ordered three-category dependent variable, perception gaps. Each model was adjusted for actual overall agreement. An alpha level of 0.05 indicated significance. All confidence intervals were calculated at 95% level. Analyses were performed using a commercially available SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

A classical content analysis (12) was performed on participants’ test responses regarding whether there was anything they would change in their practice as a result of what they learned from this program. This process allowed us to identify and describe thematic areas according to over and underestimates of diagnostic agreement.

Results

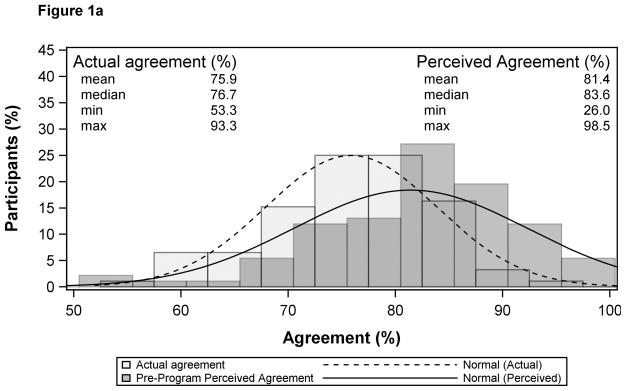

Overall (all diagnostic categories combined), participants were very accurate in their estimates of their perceived versus actual diagnostic agreement with specialist consensus diagnosis with a slight tendency to overestimate their agreement, with a mean gap between perceived vs. actual agreement of 5.5% (Mean for actual agreement = 75.9%; mean for estimated agreement = 81.4%,) (Figure 1a). Figure 1b shows the distribution in performance estimates for under-estimating (<6.7%), closely estimating (75.6%) and overestimating diagnostic agreement (>17.7%). As indicated in Table 1, non-academic affiliated pathologists were more likely to more closely estimate their performance relative to academic affiliated pathologists (77.6% versus 48%; p=0.001), whereas participants affiliated with an academic medical center were more likely to underestimate agreement with their diagnoses compared to non-academic affiliated pathologists (40% versus 6%). In addition, those who perceived that their colleagues consider them an expert in breast pathology were more likely to underestimate their agreement (41.2% versus 9.3%; 0.029) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Distribution of Overall Perceived Agreement and Actual Agreement (n=92)

Note: Extreme values omitted from plot.

Figure 1b. Distribution of Performance Gap (n=92)

Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Ho: mean of the difference = 0): p<0.001.

Performance gap mean (μ) and standard deviation is 5.5% (12.2%)

Under Estimated Performance occurs below -6.7% and Over Estimated Performance occurs above 17.7%

Table 1.

Demographic and Practice Characteristics of Participants According to Estimates of Performance Gap (Perceived Agreement with Reference Diagnosis) All Diagnostic Groups Combined (Benign, Atypia, Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Invasive) (n=92)

| Participant Characteristics | Performance Gap * | p-value† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (col %) | Under Estimated Performance n (row %) | Closely Estimated Performance n (row %) | Over Estimated Performance n (row %) | ||

| Total | 92 (100.0) | 14 (15.2) | 64 (69.6) | 14 (15.2) | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Mean Age (standard deviation) | 49 ± 8.7 | 47 ± 6.4 | 48 ± 8.1 | 56 ± 9.9 | 0.32 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 56 (60.9) | 5 (8.9) | 42 (75.0) | 9 (16.1) | 0.095 |

| Female | 36 (39.1) | 9 (25.0) | 22 (61.1) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Training and Experience | |||||

| Fellowship training in surgical or breast pathology | |||||

| No | 47 (51.1) | 7 (14.9) | 30 (63.8) | 10 (21.3) | 0.32 |

| Yes | 45 (48.9) | 7 (15.6) | 34 (75.6) | 4 (8.9) | |

| Affiliation with academic medical center | |||||

| No | 67 (72.8) | 4 (6.0) | 52 (77.6) | 11 (16.4) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 25 (27.2) | 10 (40.0) | 12 (48.0) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Do your colleagues consider you an expert in breast pathology? | |||||

| No | 75 (81.5) | 7 (9.3) | 55 (73.3) | 13 (17.3) | 0.029 |

| Yes | 17 (18.5) | 7 (41.2) | 9 (52.9) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Breast pathology experience(yrs) | |||||

| < 10 | 35 (38.0) | 5 (14.3) | 24 (68.6) | 6 (17.1) | 0.90 |

| 10–19 | 28 (30.4) | 8 (28.6) | 20 (71.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ≥ 20 | 29 (31.5) | 1 (3.4) | 20 (69.0) | 8 (27.6) | |

| Breast specimen case load (%) | |||||

| < 10 | 48 (52.2) | 5 (10.4) | 37 (77.1) | 6 (12.5) | 0.092 |

| ≥ 10 | 44 (47.8) | 9 (20.5) | 27 (61.4) | 8 (18.2) | |

| No. Breast cases (per week) | |||||

| < 5 | 26 (28.3) | 5 (19.2) | 16 (61.5) | 5 (19.2) | 0.059 |

| 5–9 | 32 (34.8) | 2 (6.3) | 27 (84.4) | 3 (9.4) | |

| ≥ 10 | 34 (37.0) | 7 (20.6) | 21 (61.8) | 6 (17.6) | |

| Perceptions about Breast Interpretation | |||||

| How challenging is breast pathology? | |||||

| Easy (0,1,2) | 44 (47.8) | 5 (11.4) | 33 (75.0) | 6 (13.6) | 0.25 |

| Challenging (3,4,5) | 48 (52.2) | 9 (18.8) | 31 (64.6) | 8 (16.7) | |

| Beast pathology is enjoyable | |||||

| Agree | 71 (77.2) | 10 (14.1) | 50 (70.4) | 11 (15.5) | 0.69 |

| Disagree | 21 (22.8) | 4 (19.0) | 14 (66.7) | 3 (14.3) | |

| Breast pathology makes me more nervous than other types of pathology | |||||

| No | 48 (52.2) | 6 (12.5) | 33 (68.8) | 9 (18.8) | 0.98 |

| Yes | 44 (47.8) | 8 (18.2) | 31 (70.5) | 5 (11.4) | |

Note: low cutoff point is mean − 1 standard deviation (12.0) is −7.0 and high cutoff point is mean + 1 standard deviation is 18.0 where mean is 6.0 and standard deviation is 12.0

Performance Gap is the difference between actual agreement and the weighted average perceived agreement for four diagnostic classes (mapping 1) of breast cancer

p-value for cumulative logit model adjusted for actual agreement

The vast majority of participants indicated that, within the entire spectrum of breast pathology, the type of cases included in the sample sets were either often (51.7%) or always (24.7%) seen in their practice, and though not statistically significant, were able to fairly closely estimate their agreement with the specialist consensus diagnoses (Table 2). Prior to the continuing medical education program, nearly 55% (54.9%) of participants could not estimate whether they would over-interpret the cases or under-interpret them relative to the reference diagnosis. Nearly 80% (79.8%) reported learning new information from this individualized web-based continuing medical education program as well as strategies they can apply to their own clinical practice (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants Reactions to Test Set Difficulty and Continuing Medical Education in General According to Perceived Agreement with Reference Diagnosis (Performance Gap) - All Diagnostic Groups Combined (Benign, Atypia, Ductal Carcinoma In Situ, Invasive) (n=92)

| Participant Characteristics | Performance Gap * | p-value† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (col %) | Under Estimated Performance n (row %) | Closely Estimated Performance n (row %) | Over Estimated Performance n (row %) | ||

| Perceptions of Test Set Difficulty (pre-program only unless otherwise noted) | |||||

| Within the entire spectrum of breast pathology you see in your practice, how similar were the types of cases included in the sample sets? | |||||

| I never see cases like these | 0 (0.0) | 0 (.) | 0 (.) | 0 (.) | 0.047 |

| I sometimes see cases like these | 21 (23.6) | 4 (19.0) | 14 (66.7) | 3 (14.3) | |

| I often see cases like these | 46 (51.7) | 5 (10.9) | 38 (82.6) | 3 (6.5) | |

| I always see cases like these | 22 (24.7) | 4 (18.2) | 11 (50.0) | 7 (31.8) | |

| Relative to breast cases you review in practice over the course of a year, did you find these sample sets: | |||||

| Less Challenging | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.38 |

| Equally Challenging | 60 (67.4) | 9 (15.0) | 43 (71.7) | 8 (13.3) | |

| More Challenging | 27 (30.3) | 4 (14.8) | 18 (66.7) | 5 (18.5) | |

| Continuing Medical Education Experiences | |||||

| How many hours of continuing medical education in breast pathology interpretation (not including this program) did you complete last year: | |||||

| None | 16 (17.6) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (62.5) | 3 (18.8) | 0.20 |

| 1 – 5 hours | 35 (38.5) | 6 (17.1) | 24 (68.6) | 5 (14.3) | |

| 6 – 8 hours | 14 (15.4) | 1 (7.1) | 13 (92.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 9 – 12 hours | 6 (6.6) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | |

| 13 – 18 hours | 6 (6.6) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | |

| >18 hours | 14 (15.4) | 1 (7.1) | 10 (71.4) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Which of the following types of continuing medical education do you most prefer: | |||||

| Instructor-led Programs | 60 (65.9) | 8 (13.3) | 44 (73.3) | 8 (13.3) | 0.55 |

| Self-Directed Programs | 24 (26.4) | 6 (25.0) | 15 (62.5) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Other | 7 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Alignment of Perceptions | |||||

| If you and the continuing medical education breast pathology experts disagree on some cases, do you think it would be more likely that you would: | |||||

| Over interpret the case | 25 (27.5) | 5 (20.0) | 19 (76.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.72 |

| Under interpret the case | 16 (17.6) | 3 (18.8) | 12 (75.0) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Unsure/Don’t Know | 50 (54.9) | 6 (12.0) | 32 (64.0) | 12 (24.0) | |

| When you and the breast pathology experts disagreed on a case the experts called atypia was it more likely that you: (post-program only) | |||||

| Over interpreted the case (call it more serious than experts) | 32 (34.8) | 4 (12.5) | 23 (71.9) | 5 (15.6) | 0.91 |

| Under interpret the case (call it less serious than experts) | 41 (44.6) | 6 (14.6) | 28 (68.3) | 7 (17.1) | |

| No trend for either over or under interpretation | 19 (20.7) | 4 (21.1) | 13 (68.4) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Did you learn new information and strategies that you can apply to your work or practice? (post-program only) | |||||

| No | 18 (20.2) | 5 (27.8) | 12 (66.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0.75 |

| Yes | 71 (79.8) | 8 (11.3) | 50 (70.4) | 13 (18.3) | |

note: low cutoff point is mean − 1 standard deviation (12.0) is −7.0 and high cutoff point is mean + 1 standard deviation is 18.0 where mean is 6.0 and standard deviation is 12.0

Performance Gap is the difference between actual agreement and the weighted average perceived agreement for four diagnostic classes (mapping 1) of breast cancer

p-value for cumulative logit model adjusted for actual agreement

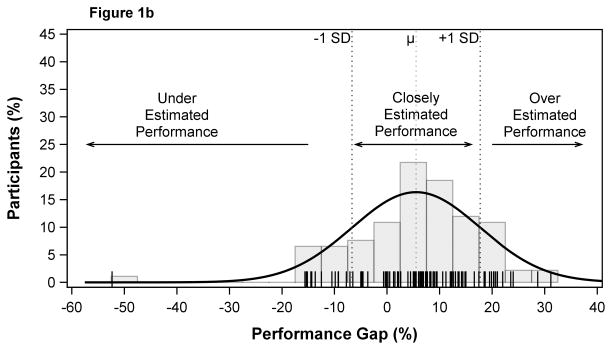

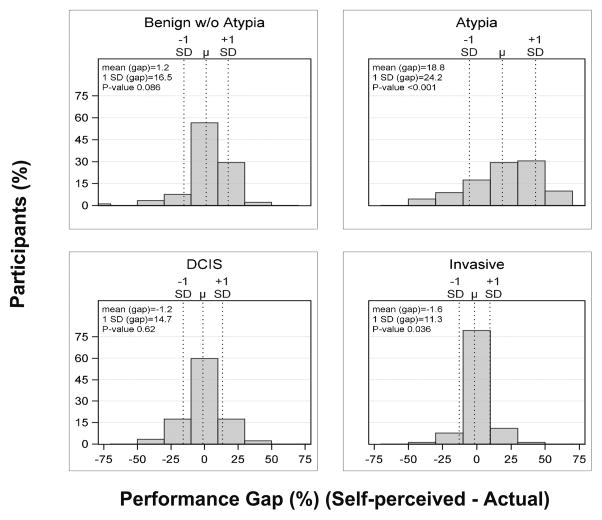

Figure 2 illustrates that participants were most likely to overestimate their performance for atypia and least likely to overestimate their performance for invasive cancer prior to the educational intervention. Figure 3 shows that following the continuing medical education program, participants were more able to recognize the gap in their estimated versus actual agreement. Twenty-two of 92 participants (23.9%) indicated areas in their clinical practice they would change as a result of the continuing medical education program (Table 3). Among those who underestimated agreement with their diagnosis, threshold setting and information seeking were equally described, while among those who overestimated agreement with their diagnoses, more careful review of cases was most frequently described. Even those who closely estimated performance often reported intending to seek more consultations.

Figure 2.

Perceived vs. Actual Agreement with Reference Diagnoses Before the Educational Intervention According to Diagnostic Category (n=92)

Figure 3. Perceived vs. Actual Agreement with Reference Diagnoses Before and After the Educational Intervention According to Diagnostic Category (n=92).

0 indicates perfect alignment between perceived and actual agreement, < 0 indicates underestimated agreement and > 0 indicates overestimated agreement

Table 3.

Areas of Practice Change Toward Improving Clinical Performance According to Whether they Over, Under, or Closely Estimated Their Performance (n=22)

| Perceived Interpretive Performance | Thematic Area of Practice Change | Exemplars in Response to the Question: Is there anything you would change in your practice as a result of what you have learned? |

|---|---|---|

| Under-estimated | ||

| Threshold Setting | • I think I am under-diagnosing atypia. Any under-diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ bothers me a bit less, as I m likely to show it to colleagues and atypia should trigger the appropriate clinical response at our institution. However, lowering my threshold for atypia is very useful to know. | |

| Information Seeking | • Continue breast focused continuing medical education | |

| Threshold Setting | • Refine thresholds. I do not agree with how this course handled FEA (perhaps there will be chance for additional comments subsequently) | |

| Information Seeking | • Better understanding of breast atypia diagnostic terminology | |

| Closely Estimated | ||

| Consultation | • Take greater care to call benign lesions with variable proliferative changes and show to colleague to r/o | |

| More Careful Review | • More alert for atypical changes and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. | |

| More Careful Review | • Pay more attention to details in mildly atypical cases | |

| Threshold Setting | • Consider shifting threshold lower for calling atypical lesions | |

| Consultation | • Share more borderline cases with colleagues | |

| Threshold Setting | • I will adjust my level of calling atypia and Ductal Carcinoma In Situ | |

| Threshold Setting | • Back off some of my Ductal Carcinoma In Situ diagnoses. | |

| Threshold Setting | • I may need to adjust my threshold for Ductal Carcinoma In Situ diagnosis. | |

| Consultation/Confidence | • Continue use of breast consultation. Better comfort with atypical hyperplasia. | |

| Consultation | • Although I show all atypical cases in my practice to another colleague, I feel that even though I am in line with many other pathologist in practice I would show more of my benign cases to check that I am not missing any atypical cases. | |

| Confidence | • Better comfort level with columnar cell changes | |

| Overestimated | ||

| More Careful Review | • Interpretation of atypical proliferation. | |

| More Careful Review | • I would apply the criteria/new information I have learned to my practice. | |

| More Careful Review | • To review more information in the atypia category, since compared with current experts I seem to be less aggressive in calling atypia | |

| Consultation | • Review more cases with my staff. | |

| Consultation | • I have more understanding of the differentiation of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ and atypical ductal hyperplasia. I over called atypia compared to experts and have never had much confidence in this area. I rely on associates who are considered breast experts in my practice and will continue to do so. This course reinforces my current practice. | |

| Threshold Setting | • Change my threshold for atypia | |

| More Careful Review | • I would be a little stronger of atypias, and I would think about them more. | |

Discussion

This study is, to our knowledge, the first detailed analysis of the perceptions pathologists have regarding the gap in perceived versus actual diagnostic agreement in breast pathology interpretation. The characteristics most likely associated with underestimating agreement with their diagnoses were affiliation with an academic medical center and their self-report of being perceived as an expert in breast pathology by colleagues. It may be that pathologists affiliated with an academic medical center or who are perceived by their colleagues as experts in breast pathology by their peers are more aware of areas of poor diagnostic agreement in breast pathology and so have lower expectations for diagnostic agreement than those with other clinical experiences, especially in diagnostic categories like atypia. It may also be that breast pathologists exposed to a high volume of consults, such as those who practice in tertiary care centers or other high volume centers, see a broader array of difficult cases, which results in less inherent confidence that they can predict the biologic behavior of the disease or be assured that their expert peers would arrive at the same diagnosis.

While research in visual interpretive practice has examined the learning curve post residency with radiologists (14, 15), this topic has not been studied with breast pathologists. In addition, both prior radiology studies focused on learning curves at the beginning of independent practice, rather than among a broad range of physician ages. We found that physicians were most likely to overestimate their diagnostic agreement rates with atypia and least likely to over or underestimate these rates for invasive cancer. Many studies have shown less interpretive variability in distinguishing between just two categories: benign and malignant (6, 8). It appears to become much more challenging when pathologists must differentiate between atypia and ductal carcinoma in situ (6–8). Given that this clinical conundrum is well documented, understanding how to reduce this variability could improve clinical practice. Our hope is that educational interventions, similar to the one we developed for this study, will result in improved clinical care.

Maintenance of Certification has stimulated similar novel educational programs for continued professional development, as gaps in professional practice are recognized. The Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education has adopted the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s definition of a gap in professional practice as ‘the difference between health care processes or outcomes observed in practice, and those potentially achievable on the basis of current professional knowledge’ (16). With changes in Maintenance of Certification occurring in subspecialties, many groups are redesigning continuing medical education to examine gaps between actual and optimal practice. For example, the American College of Physicians is currently hosting an educational program on cardiovascular risk reduction (17) aimed at identifying and addressing gaps in knowledge and practice to improve the care of patients. As with our study, it will be vitally important to determine whether such educational programs can improve both physician practice and patient outcomes so the changes in Maintenance of Certification can be linked to actual improvements. Our previously published work identified high diagnostic disagreement rates for atypia in breast pathology, and the current study’s continuing medical education intervention identified a gap in pathologists’ perception of how frequently their diagnoses would agree with the specialist reference diagnoses of atypia. This continuing medical education is novel because it focused on problematic diagnostic areas (such as atypia) that are less clearly defined than areas that are frequently tested with typical continuing medical education activities (such as invasion versus no invasion).

Very little is known about how physicians recognize and process gaps in diagnostic agreement. Our study is unique in that we studied the gap between perceived versus actual practice when interpreting test sets. This is important because research shows that for physicians to change practice behaviors they must be motivated by an understanding of a need to change, which was an important focus of this study. Most studies focus on recognizing and rewarding performance that is of high quality (18, 19) or report performance gaps at health system levels without detailing how individual physicians processed their own gaps in performance (20–21). We found that after recognizing the gap in perceived diagnostic agreement, those who underestimated agreement with their diagnoses reported that setting different clinical thresholds for interpretation and seeking additional information would be steps they would undertake to improve performance. This suggests that web-based learning loops composed of assessment followed by time-limited access to educational tools and visual diagnostic libraries may be useful in improving performance with a reference standard; when the time limit expires, the participant would repeat the loop with another assessment. This “training set” could help improve diagnostic concordance with a reference standard in actual practice. Physicians who overestimated their diagnostic agreement rates reported they would undertake more careful review as a way to improve. Physicians who closely estimated their diagnostic agreement rates most often reported intending to seek additional consultations, likely because of a good perception of how low diagnostic agreement is in breast pathology for diagnoses such as atypia. These strategies might indeed improve performance if they were implemented, but understanding if this happened and what the impact might be was beyond the scope of this study.

A strength of this study is that a broad range of pathologists participated, including university-affiliated and private-practice pathologists, pathologists with various levels of expertise in breast pathology and pathologists with various total years in practice. Another strength of the study is that we oversampled challenging cases (atypia) in a effort to focus on interventions to address the most problematic areas of breast pathology. Limitations of the study include the fact that study was limited to cases in the study test sets. In addition, the educational program necessarily used digital images of the glass slides to educate physicians about specific features of the slides that contributed to the reference diagnosis. It is possible that the digital slide images were to some extent dissimilar from the actual glass slides, which could have influenced what pathologists learned from the program.

In conclusion, our unique individualized web-based educational program helped pathologists to understand gaps in their perceived versus actual diagnostic agreement rates when their interpretations of breast biopsy cases were compared with a reference standard. We found that pathologists can closely estimate their overall diagnostic agreement with a reference standard in breast pathology but in particularly problematic areas (such as atypia), they tend to over-estimate agreement with their diagnosis. Pathologists who both over and under interpreted their diagnostic agreement rates could identify strategies that could help them improve their clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers* R01 CA140560, R01 CA172343, UO1 CA70013, U54 CA163303 and by the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium award number HHSN261201100031C. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The collection of cancer and vital status data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the U.S. For a full description of these sources, please see: http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/work/acknowledgement.html.

References

- 1.American Board of Medical Specialties. [accessed 9/29/14];American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification. http://www.abms.org/maintenance_of_certification/ABMS_MOC.aspx.

- 2.American Board of Pathology. [accessed 9/29/14];Maintenance of Certification 10-Year Cycle Requirements Summary. http://www.abpath.org/MOC10yrCycle.pdf.

- 3.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq. [accessed 9/29/14];2010 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/html/PLAW-111publ148.htm.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [accessed 9/29/14];Physician Quality Reporting System: Maintenance of Certification Program Incentive Made Simple. 2014 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2014_MOCP_IncentiveMadeSimple_Final11-15-2013.pdf.

- 5.Davis DA, Thomson M, Oxman AD, Haynes B. Changing Physician Performance: A Systematic Review of the Effect of Continuing Medical Education Strategies. JAMA. 1995;274:700–705. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.9.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmore JG, Longton GM, Carney PA, Geller BM, Onega T, Tosteson ANA, Nelson H, Pepe MS, Allison KH, Schnitt SJ, O’Malley FP, Weaver DL. Diagnostic Concordance Among Pathologists Interpreting Breast Biopsy Specimens. JAMA. 2015;313:1122–1132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells WA, Carney PA, Eliassen MS, Grove MR, Tosteson AN. Agreement with Expert and Reproducibility of Three Classification Schemes for Ductal Carcinoma-in-situ. Am J Surg Path. 2000;24:641–659. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells WA, Carney PA, Eliassen MS, Tosteson AN, Greenberg ER. A Statewide Study of Diagnostic Agreement in Breast Pathology. JNCI. 1998;90:142–144. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oster N, Carney PA, Allison KH, Weaver D, Reisch L, Longton G, Onega T, Pepe M, Geller BM, Nelson H, Ross T, Elmore JG. Development of a diagnostic test set to assess agreement in breast pathology: Practical application of the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies. BMC Women’s Health. 2013;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney PA, et al. The New Hampshire Mammography Network: the development and design of a population-based registry. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:367–72. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.2.8686606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. [Accessed 9/29/14]; Available at: http://breastscreening.cancer.gov/

- 12.Krippendorf K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 3. Sage Publications; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunning D. Science American Medical Association Series: Psycology American Medical Association on accuracy and illusion in self-judgement. [Accessed 4/1/15];The New REDDIT Journal of Science. http://www.reddit.com/r/science/comments/2m6d68.

- 14.Miglioretti DL, Gard CC, Carney PA, Onega T, Buist DSM, Sickles EA, Kerlikowske K, Rosenberg RD, Yankaskas BC, Geller BM, Elmore JG. When radiologists perform best: The learning curve in screening mammography interpretation. Radiology. 2009;253:632–640. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pusic M, Pecaric M, Boutis K. How much practice is enough? Using learning curves to assess the deliberate practice of radiograph interpretation. Acad Med. 2011;86:731–736. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182178c3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. [accessed 10/6/14];Professional practice gap. http://www.accme.org/ask-accme/criterion-2-what-meant-professional-practice-gap.

- 17.American College of Physicians. [accessed 10/06/14];American Board of Internal Medicine Maintenance of Certification Practice Improvement. http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/quality_improvement/projects/cardio.htm.

- 18.Rosenthal MB, Fernandopulle R, HyunSook RS, Landon B. Paying For Quality: Providers’ Incentives For Quality Improvement. Health Aff. 2004;23:127–141. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams RG, Dunnington GL, Roland FJ. The Impact of a Program for Systematically Recognizing and Rewarding Academic Performance. Acad Med. 2003;78:156–166. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steurer-Stey C, Dallalana K, Jungi M, Rosemann T. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Swiss primary care: room for improvement. Qual Prim Care. 2012;20:365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffey RT, Chen BC, Krehbiel NW. Performance in appropriate Rh testing and treatment with Rh immunoglobulin in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]