Abstract

The risk for misuse of opioid medications is a significant challenge in the management of chronic pain. The identification of those who may be at greater risk for misusing opioids is needed to facilitate closer monitoring of high-risk subgroups, and may help to identify therapeutic targets for mitigating this risk. The aim of this study was to examine whether distress intolerance--the perceived or actual inability to manage negative emotional and somatic states--was associated with opioid misuse in those with chronic pain. A sample of 51 participants prescribed opioid analgesics for chronic back or neck pain were recruited for a one-time laboratory study. Participants completed measures of distress intolerance and opioid misuse, and a quantitative sensory testing battery. Results suggested that distress intolerance was associated with opioid misuse, even controlling for pain severity and negative affect. Distress intolerance was not associated with pain severity, threshold or tolerance, but was associated with self-reported anxiety and stress following noxious stimuli. This study found robust differences in distress intolerance between adults with chronic pain with and without opioid medication misuse. Distress intolerance may be a relevant marker of risk for opioid misuse among those with chronic pain.

Keywords: opioids, opioid misuse, chronic pain, distress tolerance

Although many individuals with chronic pain are able to adhere to a prescribed opioid analgesic regimen, a significant percentage of chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy will misuse their medication.3, 52 This presents a significant challenge to providers trying to manage chronic pain while mitigating the risk of opioid misuse and its adverse consequences (e.g., the development of opioid use disorder). The ability to identify patients at greater risk for opioid misuse would allow for closer monitoring of this subgroup, and may provide targets for intervention to reduce medication misuse. Accordingly, much research in this area has focused on identifying risk factors for opioid misuse.

A history of a substance use disorder consistently appears to confer risk for opioid medication misuse.1, 11, 17, 36 Support is mixed for a wide range of other variables, such as younger age, history of legal problems, and presence of mood disorders.49 Optimal prediction may require consideration of multiple risk variables; multivariable screening tools have been developed that have enhanced the ability to detect those at risk.9, 11, 25 Although much progress has been made in identifying risk factors, the ability to predict those who will misuse their medication remains limited,12 and the mechanisms underlying this increased risk remain largely unknown.

Understanding risk at the mechanistic level yields the ability to not only identify those in need of closer monitoring, but potentially to intervene to reduce the likelihood of misuse. The identification of mechanisms underlying elevated risk--particularly those that can be mitigated with intervention--is crucial to improving our understanding of prescription opioid misuse and to developing and refining prevention and treatment strategies.

Distress intolerance, an important vulnerability factor in substance use disorders,4, 7, 34 is a particularly strong candidate for such a mechanism. Distress intolerance is defined as the perceived or actual inability to handle aversive somatic or emotional states. Importantly, distress intolerance is modifiable with behavioral interventions,32 and treatments designed to reduce distress intolerance have demonstrated preliminary efficacy for those with substance use disorders,2, 6 including opioid-dependent patients. 41, 48 The overarching aim of this study was to examine distress intolerance as a potential mechanism underlying prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain.

The perception that one cannot tolerate distress motivates a wide range of behaviors intended to quickly avoid or escape distress, such as avoidance, 21, 50 risk-taking, 28 substance use, 5, 8 and non-suicidal self-injury.38 Such seemingly diverse “quick-fix” behaviors share the ability to provide strong, proximal negative reinforcement. For those who are highly intolerant of distress, a strategy that provides rapid relief may both be particularly reinforcing,40 and become relied upon to the exclusion of more adaptive behaviors. Consistent with this perspective, distress intolerance is associated with the use of highly reinforcing substances, such as nicotine 5 and heroin, 34 and is associated with using substances to cope with negative emotional states. 22, 54

Among those with chronic pain, the inability to tolerate pain and emotional responses to pain may motivate opioid use (beyond that prescribed) to provide rapid relief from these states. Greater motivation to seek rapid relief from opioids may increase risk for misusing opioids, and may maintain problematic opioid use over time. Indeed, individuals with chronic pain who have greater sensory 18 and cognitive 30 reactivity to pain are at elevated risk for prescription opioid misuse. Greater psychiatric severity and negative affect also appear to increase risk for misuse in this population.51 Taken together, this research suggests that those with chronic pain who misuse their opioids exhibit higher levels of distress in general, as well as heightened reactivity to that distress, both of which may be reflective of poor regulation of these states.

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether distress intolerance was associated with opioid misuse among individuals with chronic pain receiving long-term opioid treatment. We hypothesized that participants with higher distress intolerance would be more likely to misuse opioids. In a secondary aim, we examined the association between distress intolerance and pain sensitivity, pain threshold, and subjective pain intensity. This exploratory aim examined whether elevations in distress intolerance were reflective of heightened reactivity to noxious stimuli.

Method

Participants

The study sample was recruited from the pain management clinic of a large, urban academic hospital. Patients receiving treatment at the clinic were recruited via posted advertisements and mailings from research staff. Patients were eligible for the study if they met the following criteria: (1) age 18-70 years; (2) presence of chronic back pain (defined as more than 3 months of pain, at an average severity of 4 or higher on a 0-10 scale); and (3) current prescription for an opioid analgesic medication for pain. Exclusion criteria for this study included variables contraindicated for the psychophysical testing or other study procedures, including (1) presence of an active infection; (2) significant arm or shoulder pain (due to potential interference with performance on study computer tasks); (3) history of myocardial infarction or other serious cardiovascular condition (due to potential contraindication with psychophysical testing procedures); (4) other acute major psychiatric or medical condition that would interfere with the ability to engage in the experimental session (e.g., current significant impairment in the ability to engage in tasks requiring sustained attention; no participants were excluded for this reason); and (5) current peripheral neuropathy, active vasculitis, or severe peripheral vascular disease. Interested individuals completed a screening procedure with a member of the study staff to determine eligibility; those who met eligibility criteria were then scheduled for an informed consent meeting.

A sample of 51 participants (24 women) was enrolled in the study. The mean age was 54.6 years (SD=8.4). The majority of the study self-identified race as Caucasian (72.5%), followed by African American (19.6%), Other (3.9%), Asian (2%) and American Indian or Alaskan Native (2%). A small proportion (3.9%) self-identified as Hispanic or Latino/a. Educational attainment was heterogeneous: 3.9% completed less than high school, 15.7% completed high school, 35.3% completed some college, 35.3% completed college, and 9.8% completed a graduate degree.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the McLean Hospital institutional review board. Following provision of informed consent, participants completed a battery of self-report measures. Study staff then administered a behavioral measure of distress intolerance and a psychophysical testing battery (see below for description); the order of these two procedures was randomly assigned to control for potential order effects.

Measures

Accurately defining prescription opioid misuse among those receiving opioid treatment is challenging because of potential overlap between substance use disorder symptoms and appropriate use of prescribed opioids (e.g., tolerance, withdrawal). In this study, we used a multiple-source method to maximize the likelihood of accurately detecting opioid misuse, consistent with prior studies. 23 Specifically, two measures of opioid misuse were administered. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure 10 is a 17-item self-report measure of prescription opioid misuse. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure has demonstrated strong sensitivity and specificity for the identification of opioid misuse. 10 Internal consistency reliability in the current sample was strong (alpha = .86). The Addiction Behaviors Checklist 53 is a 20-item measure of addiction-like behaviors that was developed to measure prescription opioid addiction in chronic pain patients. The Addiction Behaviors Checklist, which has demonstrated strong validity and interrater reliability in a longitudinal study, 53 was assessed via chart review to assess the presence of any of these behaviors as reported by the treating physician. Because not all participants would have seen a physician within the past 30 days, but all had seen a physician within the past year, visits were examined over a one-year period to ensure that these data could be collected for all participants. This chart review was completed independently by two study staff members. These ratings were then compared for reliability; discrepancies were discussed with a senior member of the study staff.

For the purpose of this study, we defined opioid misuse using the following criteria: (1) a score above the validated clinical cut-off on the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (9 or higher), (2) 3 or more addictive behaviors on the Addiction Behaviors Checklist, or (3) evidence in the medical chart of a positive urine drug screen for a non-prescribed opioid or illicit drug in the past 30 days.

Pain severity was measured using the self-report Brief Pain Inventory, 13 a widely used measure of pain severity that has demonstrated strong construct validity and internal consistency reliability in chronic pain samples. 19, 47 In the current sample, the internal consistency reliability was strong for the pain severity subscale (alpha = .82).

Distress intolerance was measured using both self-report and behavioral measures. Both methods were used because of evidence that these methods measure different facets of distress intolerance. Specifically, behavioral measures of distress intolerance allow for the measurement of intolerance of specific domains of distress, such as frustration, whereas self-report measures allow for a more general assessment of distress intolerance. 33, 44

The Distress Intolerance Index 35 is a 10-item self-report measure of distress intolerance that was derived from an analysis of previously validated measures, including the Anxiety Sensitivity Index, 42 the Distress Tolerance Scale, 43 and the Frustration Discomfort Scale. 20 Each item (for example “I can't handle feeling distressed or upset.”) is rated on a 5-point scale with responses reflecting the degree to which each statement describes the respondent (ranging from “very little” to “very much”). Possible scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores representing more distress intolerance. The Distress Intolerance Index has demonstrated strong internal consistency reliability and strong concurrent validity with behavioral measures of distress intolerance, 33 and sensitivity to changes in treatment. 32 Internal consistency in the current sample was strong (alpha = .85).

The Computerized Mirror Tracing Persistence Task (Strong, Lejuez, Daughters, Marinello, Kahler, & Brown. The Computerized Mirror Tracing Task Version 1. Unpublished Manual, 2003) is a computer-based distress intolerance measure. The task entails tracing the shape of a star using the computer's mouse, with the feedback from the mouse reversed to replicate the effect of tracing a mirror image. This task is designed to be highly challenging and provides negative feedback (a loud buzz) after each error, which reliably induces frustration. Thus, continuing to engage in the task requires persistence toward a goal-driven behavior, while tolerating this frustration. Participants are given the opportunity to discontinue or quit at any time; this time to discontinuation (i.e., behavioral persistence) is used as an index of distress intolerance. Participants were provided with a monetary incentive to enhance motivation to persist at the task. All participants were informed that if they were among the top performers on the task that they would be entered into a raffle to receive a $40 gift card to a local vendor. In fact, all participants were entered into the raffle so as to not differentially compensate those with higher functioning in this domain; this element of deception was reviewed during a standard debriefing.

Psychophysical Testing

A brief Quantitative Sensory Testing session was also conducted. All procedures were non-invasive, non-tissue-damaging, and have been frequently used in prior studies of patients with chronic pain. 14 Verbal ratings of current clinical pain (on a 0-100 scale, “no pain” to “the most intense pain imaginable”) were obtained prior to psychophysical testing, and were reassessed periodically throughout the session. Current anxiety ratings (also on a 0-100 scale, with the anchors “no anxiety” – “severe anxiety”) were collected periodically throughout the session.

Mechanical pain thresholds were evaluated using a digital pressure algometer (Somedic; Sollentuna, Sweden). Pressure pain thresholds were determined bilaterally at two anatomic locations; the belly of the trapezius muscle and the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. Two trials were performed bilaterally at each site (for a total of 8 trials). In each trial, mechanical force was applied by an experimenter using the 0.5 cm2 probe; pressure was increased at a steady rate of 30 kilopascals until the subject indicated that the pressure was “first perceived as painful.”

Mechanical temporal summation was determined using weighted pinprick simulators. Temporal summation involves psychophysical testing of the increase in pain across a series of repeated, identical noxious stimuli; it is often used as an index of pain sensitization, or endogenous pain-facilitatory processes. The lowest-force simulator that produced a painful sensation with a single stimulus (128 or 256 millinewtons for most subjects) was then used to apply a series of 10 stimuli to the skin on the intermediate section of the middle finger at a rate of 1 per second. Participants reported a pain intensity rating (on a 0-100 scale, “no pain” to “the most intense pain imaginable”) for the first, fifth, and tenth stimulus. A rating of any ongoing after-sensation pain was obtained at 15 seconds after the application of the final stimulus.

Finally, we assessed responses to noxious cold with repeated cold pressor tasks. Each cold pressor task involved immersion of the participant's right hand in a circulating cold water bath (maintained at 4°C). Participants completed a series of 3 trials, with the first 2 consisting of immersions of the right hand for 30 sec, with 2 min between immersions. The 3rd and final cold pressor task involved an immersion of the right hand lasting until a participant reached pain tolerance (or a 3 min maximum). During each task and after the task, participants rated perceived cold pain intensity on a 0-100 scale.

During the first two cold pressor tasks, conditioned pain modulation was also assessed during the cold water immersion. Conditioned pain modulation is a non-invasive test of endogenous pain-inhibitory systems using a heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation paradigm. During each cold pressure task, pressure pain threshold was determined on the contralateral (left) trapezius muscle. Conditioned pain modulation was quantified as the percent change in pressure pain threshold during the cold pressor task compared to baseline pressure pain threshold on the left trapezius. In general, if an individual's endogenous inhibitory systems are working effectively, an increase in pressure pain threshold during a concurrent cold pressor task is expected. 37

Data Analysis

Participants with and without opioid misuse were compared on sociodemographic and clinical variables using t-tests and Χ2 tests. Variables for which significant differences were detected between groups were included as covariates in the analysis of the main study aims. The Mirror Tracing Persistence Task, like other behavioral persistence measures, can exhibit ceiling effects; thus, these data were screened to determine whether a continuous or dichotomous (did the participant persist or not) definition was the most appropriate data analytic approach.

The association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse was tested using a series of logistic regressions, with opioid misuse status as the dependent variable. Due to the association between pain severity and opioid misuse,24 and the link between younger age and substance use and misuse,45 these variables were included in the model to control for their potential effect on opioid misuse status. Additionally, negative affect was included as a second step in the model given its partial overlap with distress intolerance 26 and its link to opioid misuse in chronic pain patients.29 Because distress intolerance and negative affect are moderately correlated, collinearity diagnostics were calculated for regression models.

Finally, we examined the association between distress intolerance and pain responsivity during psychophysical testing. Subjective pain ratings, pain threshold, and pain tolerance during the testing protocol were first examined for skewness and univariate outliers to determine the appropriate statistical approach. Associations between these variables and both self-report and behavioral distress intolerance measures were assessed using correlations (for continuous variables) and independent-samples t-tests (for dichotomous variables). Non-parametric tests were utilized for any variable with evidence of significant skewness.

A sample of 50 participants was selected for this preliminary investigation, which provided more than sufficient degrees of freedom to obtain an estimate of the association between distress intolerance and quantitative outcomes (psychophysical testing outcomes and continuous results from the Current Opioid Misuse Measure), and a preliminary estimate of the effect of distress intolerance on opioid misuse status.

Results

Of the 51 participants in the study, 31 met criteria for opioid misuse. There were no significant differences between those with and without opioid misuse on sociodemographic variables (see Table 1). These groups also did not report significant differences in pain severity (t[49] = -0.18, p = .86).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics by Opioid Misuse Group.

| Opioid Misuse | Test Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes (n=31) | No (n=20) | (t/χ2) | p |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 53.39 (8.87) | 56.4 0 (7.37) | 1.26 | 0.21 |

| Gender (% female) | 45.16% | 50% | 0.11 | 0.74 |

| Ethnicity (% non-Hispanic/Latino) | 96% | 91.67% | ** | 1.00 |

| Race | 2.33 | 0.68 | ||

| % Caucasian | 74.19% | 70.00% | ||

| % African American | 19.35% | 20.00% | ||

| % Other Race | 6.45% | 10.00% | ||

| Education (% high school or less) | 15% | 22.58% | ** | 0.72 |

| COMM, mean (SD) | 15.52 (7.26) | 4.25 (2.14) | -6.73 | <.001 |

| PANAS Negative Affect, mean (SD) | 16.17 (6.53) | 11.21 (3.12) | -3.09 | 0.003 |

Note. COMM=Current Opioid Misuse Measure, PANAS=Positive and Negative Affectivity Scales.

Fisher's Exact Test due to small cell sizes

Four participants did not complete the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task due to software error. The Distress Intolerance Index and Mirror Tracing Persistence Task were modestly, but significantly correlated (r = -0.31, p = .03). This finding is consistent with previous studies that suggest that these measures capture overlapping, but somewhat distinct constructs. 31 However, the behavioral data exhibited a substantial ceiling effect, with 42.6% of participants persisting for the full duration of the computer tracing task. Thus, a dichotomous definition of distress intolerance was used for the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task (i.e., persist to completion of the task or discontinue prior to completion).

Distress Intolerance and Opioid Misuse

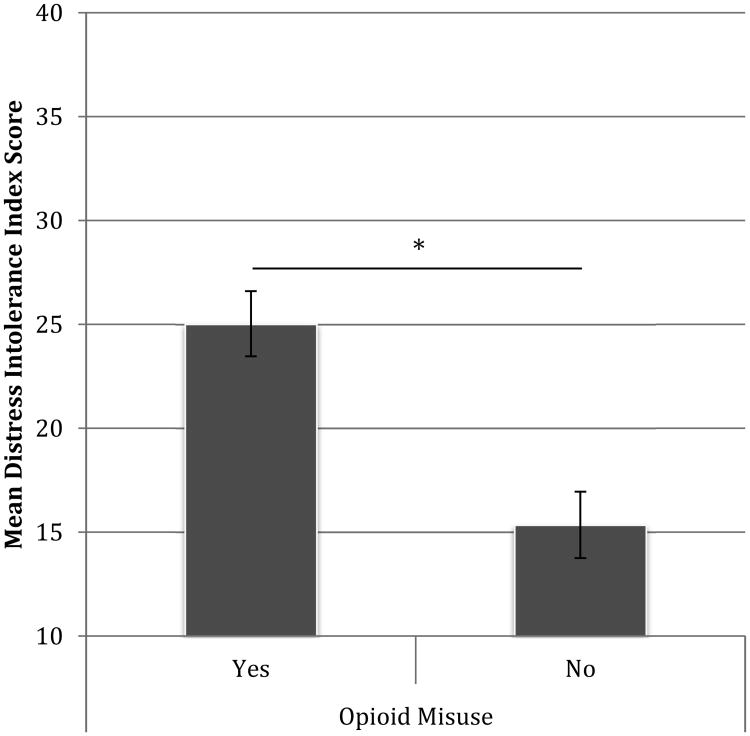

Figure 1 presents the Distress Intolerance Index scores by opioid group. Of note, the Distress Intolerance Index was also associated with the degree of opioid misuse as measured continuously by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (r = .52, p < .001), suggesting that higher levels of distress intolerance were associated with more severe opioid misuse.

Figure 1. Distress Intolerance by Opioid Misuse Group (*p<.001).

Table 2 presents the results from the logistic regression predicting opioid misuse status. This model indicated a strong association between the Distress Intolerance Index and opioid misuse (B = 0.15, SEB = .05, p = .002, OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.28). This association was slightly mitigated when controlling for negative affect (B = 0.11, SEB = .05, p = .04, OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.23); however, negative affect was not significant in this model. Examination of collinearity statistics suggested that collinearity was within an acceptable range according to the standards suggested by Belsely et al. (1980) as previously cited. 46

Table 2. Logistic Regression Predicting Opioid misuse status.

| Variable | B | SEB | OR | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 1.04 | 0.26 |

| BPI Pain Severity | 0.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 1.10 | 0.97 |

| PANAS Negative Affect | 0.16 | 0.14 | 1.17 | 0.89 | 1.54 | 0.23 |

| Distress Intolerance Index | 0.11 | 0.05 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.23 | 0.04 |

Note. BPI = Brief Pain Inventory, PANAS = Positive and Negative Affectivity Scales, OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval.

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure also includes a number of items that measure affect (e.g., anger) that may partially overlap with distress intolerance. Thus, to rule out the possibility that the association between opioid misuse status and distress intolerance was inflated due to partial measure overlap, we re-ran the regression analysis using only the 8 items on the Current Opioid Misuse Measure that directly measure medication-related behaviors. This regression also controlled for age, pain severity, and negative affect. The results indicated a strong and significant association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse behaviors (B = .26, SEB = .09, t = 2.96, p = .005).

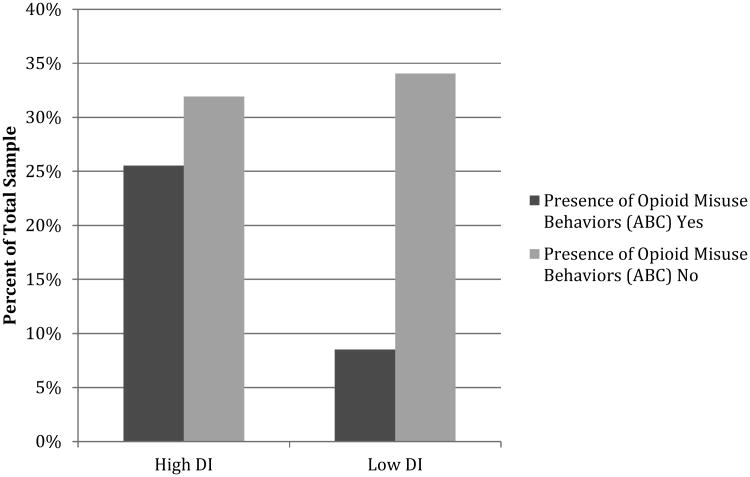

Persistence on the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task was not significantly associated with opioid misuse status (B = 0.37, SEB = .75, p = .63). The absence of a link between the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task and opioid misuse is consistent with studies that have linked self-reported distress intolerance to self-reported symptoms, and stronger links between behavioral measures and behavioral outcomes (e.g., treatment dropout, early lapse in smokers).5, 16 Accordingly, in an exploratory analysis we examined the association between the presence or absence of any behavior on the Addiction Behaviors Checklist and persistence on the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task. Results of the Χ2 test did not reach statistical significance (Χ2 = 3.06, p = .08); however, this may have been attributable to the small sample size (n=47). Those who discontinued the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task (n=27) were more than twice as likely to exhibit at least one misuse behavior on the Addiction Behaviors Checklist (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Behavioral Distress Intolerance and Presence of Opioid Misuse Behaviors.

Psychophysical Testing

The Distress Intolerance Index was not significantly associated with pain threshold, pain tolerance, or conditioned pain modulation (all Pearson's and Spearman's correlations < .30 and ns). The Distress Intolerance Index was modestly associated with maximum pain rating during the cold pressor test (Spearman's rho = -.32, p = .03), but not with pain ratings at 30, 60, or 90 seconds after the task or subjective pain ratings to mechanical pain stimuli. However, Distress Intolerance Index score was significantly associated with anxiety ratings throughout the psychophysical testing, including stress and worry prior to testing (r = .46, p = .001, r = .45, p = .001, respectively), and anxiety during (r = .37, p =. 009) and after testing (r = .34, p = .02).

Groups based on Mirror Tracing Persistence Tasks outcomes (persist to completion or discontinue) were compared on psychophysical testing outcomes, and no significant differences were found between these groups on any subjective pain ratings, pain threshold, or pain tolerance variables (see Table 3). Although those who did not persist had higher ratings on all affective variables, these did not reach statistical significance (ps ranged from .20-.61).

Table 3. Psychophysical Responses by Mirror Tracing Persistence Task Performance.

| Mirror Tracing Persistence | Test Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable, mean (SD) | Discontinued (n=26) | Completed (n=19) | Z | p |

| Mechanical Pain | ||||

| Trial 1 | 12.25(12.57) | 10.74(16.45) | -0.96 | .34 |

| Trial 5 | 16.46(16.21) | 13.34(19.67) | -0.99 | .32 |

| Trial 10 | 20.12(20.74) | 14.79(21.84) | -1.00 | .32 |

| CPM | 124.64(24.90) | 120.12(18.27) | -0.32 | .75 |

| Cold Pressor | ||||

| Maximum Pain | 77.34(22.28) | 69.36(22.22) | -1.39 | .16 |

| Pain 30sec after CP | 10.19(21.42) | 15.44(23.58) | -1.25 | .21 |

| Pain 60sec after CP | 6.06(18.20) | 5.47(15.06) | -0.54 | .59 |

| Pain 90sec after CP | 5.29(17.18) | 1.67(4.46) | -0.27 | .79 |

|

| ||||

| t | ||||

|

| ||||

| Pressure Pain Threshold | ||||

| Thumb | 396.12 (164.98) | 454.60 (121.80) | -1.27 | .21 |

| Trapezius | 466.40(237.46) | 599.25(224.96) | -1.90 | .07 |

| CP Tolerance | 54.91(50.46) | 63.36(61.40) | -0.50 | .62 |

Note. CP=cold pressor, CPM = conditioned pain modulation.

Discussion

Better understanding of the factors that place people with chronic pain at risk for misusing opioid medications is sorely needed. In particular, the identification of mechanisms that contribute to this risk has the potential to provide treatment targets, with the ultimate goal of mitigating risk in this vulnerable population. Our study found that self-reported distress intolerance—an important vulnerability factor for maladaptive avoidance and escape behaviors—was significantly associated with opioid misuse in a sample of chronic pain patients. In this cross-sectional study, for every 1-unit increase on the Distress Intolerance Index, the likelihood of being in the opioid misuse group was 12% higher. Of note, the association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse remained strong and significant even when removing any affective items from the Current Opioid Misuse Measure.

A behavioral measure of intolerance of distress, in contrast, was not associated with opioid misuse. It is possible that this disparity reflects differences in distress intolerance based on the type of distress (for the Mirror Tracing Persistence Task, frustration). Prior studies have suggested that intolerance of particular types of distress is more relevant to some outcomes and in some populations than others. 34, 44 Of note, prior studies of opioid-dependent participants have found strong differences in frustration intolerance between those who are and are not dependent on opioids. 34 In this study, frustration intolerance does not appear to distinguish opioid misuse in a population prescribed opioids; however, an exploratory analysis provided some indication that this measure was associated with physician-reported opioid misuse behaviors. Further study of this relationship in larger sample sizes is needed.

Distress intolerance was not associated with greater pain responsivity, including pain threshold, tolerance, or sensitivity. This suggests that distress intolerance is not simply reflective of an elevated sensory response to pain. Distress intolerance was associated with greater pain-related anxiety, consistent with the perspective that this construct reflects a reactivity to distress that is separate from the distress itself. This is consistent with the literature on anxiety sensitivity--a variable closely related to distress intolerance--which is defined as fear of somatic and cognitive symptoms of anxiety. 42 Anxiety sensitivity has been widely studied in clinical and nonclinical pain samples, and is strongly linked to affective responses to pain (e.g., fear of pain), with only modest aggregate associations with pain severity, threshold, and tolerance. 39 Taken together, these findings suggest that distress sensitivity and tolerance may amplify affective reactivity to pain, and thus may be important targets for mitigating the emotional impact of pain.

Distress intolerance is targeted extensively in cognitive-behavioral therapies. Although this is a relatively stable, trait-like construct, 15, 27 it can be modified with treatment. 2, 6, 32 Interventions for distress intolerance include building adaptive responses to distressing emotional states, and rehearsing awareness and tolerance of these states without resorting to an escape behavior. Further research on the prospective association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse is needed to determine whether this is a therapeutic target that may be useful in chronic pain populations. Importantly, distress intolerance may be both a risk factor for developing opioid misuse, and a maintaining factor that continues misuse over time (and may be worsened as a results of chronic opioid use). Longitudinal studies are needed to identify the nature of this relationship and the temporal sequencing of the impact of distress intolerance on opioid misuse in this population.

The association between the self-report and behavioral measures of distress intolerance in this study was significant, but modest. This is consistent with the literature suggesting low concordance between behavioral and self-report measures of distress intolerance.31 There are several possible explanations for this difference between methods of measurement. One possibility, with growing support in the literature, is that distress intolerance varies based on the type of distress. For example, intolerance of anger/frustration may be distinct from intolerance of anxiety. Several studies have supported this hypothesis, demonstrating stronger concordance between behavioral and self-report measures that capture the same type of distress.33, 44 Rival hypotheses, such as the possibility that perceived and actual intolerance reflect related, but distinct, processes should also be considered in future studies.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the study relied on self-report and chart review methods to define opioid misuse. Although we collected multiple data sources, consistent with prior studies, 23 the use of a clinician interview and/or urine toxicology screening for all participants would have further strengthened our study design. Second, due to a ceiling effect with the behavioral distress intolerance task, the power to detect differences in this outcome was limited. Future studies in larger samples are needed to examine effects on the behavioral level. We cannot rule out the contribution of method effects to these results (i.e., correlated error variance among self-report measures); however, the association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse remained significant even controlling for negative affect (also assessed using self-report). Moreover, the association between distress intolerance and anxiety, but not pain ratings during the QST session is consistent with the hypothesized mechanism of distress intolerance (i.e., amplified emotional reactivity to distress). Psychiatric disorders were not assessed in this study. Although controlling for negative affect in the analyses should mitigate the impact of psychiatric disorders to some extent, future studies should also control for the potential impact of psychiatric disorders on this association. Finally, the study design was cross-sectional and temporal precedence (and causality) can therefore not be established. Previous longitudinal studies have found that distress intolerance predicts outcomes over time; 5, 15 studies investigating whether distress intolerance predicts opioid misuse in patients initiating opioid medications are needed to determine whether distress intolerance may serve as a valuable prognostic variable for those initiating opioid therapy.

This cross-sectional study of chronic pain patients found a strong association between distress intolerance and opioid misuse. Notably, this association remained significant when controlling for negative affect, which has been previously linked to misuse in this population. Distress intolerance has been widely linked to maladaptive avoidance and escape behaviors and is an important treatment target for these disorders. Future research examining the prospective link between distress intolerance and opioid misuse is needed to determine whether this may be an important intervention target in this population to mitigate risk of medication misuse.

Perspective.

This study demonstrated that distress intolerance was associated with opioid misuse in adults with chronic pain who were prescribed opioids. Distress intolerance can be modified with treatment, and thus may be relevant not only for identification of risk for opioid misuse, but also for mitigation of this risk.

Highlights.

Opioid medication misuse is a significant public health problem.

Distress intolerance was associated with a opioid misuse in chronic pain patients.

Distress intolerance was not associated with pain severity, threshold or tolerance.

However, distress intolerance was associated with affective response to pain.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This project was supported by the following grants: R03 DA 034102 (McHugh); K24 DA022288 and UG1DA015831 (Weiss); and, R01 AR064367 and R01AG034982 (Edwards). Dr. Weiss has served on the scientific advisory board for Indivior.

Footnotes

All other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barry DT, Goulet JL, Kerns RK, Becker WC, Gordon AJ, Justice AC, Fiellin DA. Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and pain in veterans with and without HIV. Pain. 2011;152:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Hunt ED, Lejuez CW. Initial RCT of a distress tolerance treatment for individuals with substance use disorders. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012;122:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boscarino JA, Rukstalis MR, Hoffman SN, Han JJ, Erlich PM, Ross S, Gerhard GS, Stewart WF. Prevalence of prescription opioid-use disorder among chronic pain patients: comparison of the DSM-5 vs. DSM-4 diagnostic criteria. J Addict Dis. 2011;30:185–194. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2011.581961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Carpenter LL, Niaura R, Price LH. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Strong DR, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Carpenter LL, Niaura R, Price LH. A prospective examination of distress tolerance and early smoking lapse in adult self-quitters. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:493–502. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RA, Reed KM, Bloom EL, Minami H, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV, Hayes SC. Development and preliminary randomized controlled trial of a distress tolerance treatment for smokers with a history of early lapse. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2013;15:2005–2015. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: the roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, Jamison RN. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, Budman SH, Jamison RN. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R) The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2008;9:360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Miaskowski C, Passik SD, Portenoy RK. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2009;10:131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz-Almeida Y, Fillingim RB. Can quantitative sensory testing move us closer to mechanism-based pain management? Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2014;15:61–72. doi: 10.1111/pme.12230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings JR, Bornovalova MA, Ojanen T, Hunt E, MacPherson L, Lejuez C. Time doesn't change everything: the longitudinal course of distress tolerance and its relationship with externalizing and internalizing symptoms during early adolescence. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2013;41:735–748. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Brown RA. Distress tolerance as a predictor of early treatment dropout in a residential substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2005;114:729–734. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards RR, Wasan AD, Michna E, Greenbaum S, Ross E, Jamison RN. Elevated pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients at risk for opioid misuse. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12:953–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gjeilo KH, Stenseth R, Wahba A, Lydersen S, Klepstad P. Validation of the brief pain inventory in patients six months after cardiac surgery. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2007;34:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrington N. The Frustration Discomfort Scale: Development and psychometric properties. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2005;12:374–387. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington N. It's too difficult! Frustration intolerance beliefs and frustration. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:873–883. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howell AN, Leyro TM, Hogan J, Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance in relation to coping and conformity motives for alcohol use and alcohol use problems among young adult drinkers. Addict Behav. 2010;35:1144–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamison RN, Butler SF, Budman SH, Edwards RR, Wasan AD. Gender differences in risk factors for aberrant prescription opioid use. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2010;11:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamison RN, Link CL, Marceau LD. Do pain patients at high risk for substance misuse experience more pain? A longitudinal outcomes study. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2009;10:1084–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamison RN, Serraillier J, Michna E. Assessment and treatment of abuse risk in opioid prescribing for chronic pain. Pain research and treatment. 2011;2011:941808. doi: 10.1155/2011/941808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiselica AM, Rojas E, Bornovalova MA, Dube C. The Nomological Network of Self-Reported Distress Tolerance. Assessment. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1073191114559407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: a review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacPherson L, Reynolds EK, Daughters SB, Wang F, Cassidy J, Mayes LC, Lejuez CW. Positive and negative reinforcement underlying risk behavior in early adolescents. Prevention Science. 2010;11:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martel MO, Dolman AJ, Edwards RR, Jamison RN, Wasan AD. The association between negative affect and prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: the mediating role of opioid craving. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2014;15:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martel MO, Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Edwards RR. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2013;132:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh RK, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, Murray HW, Hearon BA, Gorka SM, Otto MW. Shared Variance among Self-Report and Behavioral Measures of Distress Intolerance. Cognit Ther Res. 2011;35:266–275. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHugh RK, Kertz SJ, Weiss RB, Baskin-Sommers AR, Hearon BA, Bjorgvinsson T. Changes in distress intolerance and treatment outcome in a partial hospital setting. Behavior therapy. 2014;45:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McHugh RK, Otto MW. Domain-general and domain-specific strategies for the assessment of distress intolerance. Psychology of addictive behaviors : journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:745–749. doi: 10.1037/a0025094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHugh RK, Otto MW. Profiles of distress intolerance in a substance-dependent sample. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2012;38:161–165. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McHugh RK, Otto MW. Refining the measurement of distress intolerance. Behavior therapy. 2012;43:641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michna E, Ross EL, Hynes WL, Nedeljkovic SS, Soumekh S, Janfaza D, Palombi D, Jamison RN. Predicting aberrant drug behavior in patients treated for chronic pain: importance of abuse history. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2004;28:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nir RR, Yarnitsky D. Conditioned pain modulation. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care. 2015;9:131–137. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nock MK, Mendes WB. Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem -solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:28–38. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ocanez KL, McHugh RK, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of the association between anxiety sensitivity and pain. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:760–767. doi: 10.1002/da.20681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Giedgowd GE, Conklin CA, Sayette MA. Differences in negative mood-induced smoking reinforcement due to distress tolerance, anxiety sensitivity, and depression history. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1811-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollack MH, Penava SA, Bolton E, Worthington JJ, 3rd, Allen GL, Farach FJ, Jr, Otto MW. A novel cognitive-behavioral approach for treatment-resistant drug dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the predictions of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sirota AD, Rohsenow DJ, Mackinnon SV, Martin RA, Eaton CA, Kaplan GB, Monti PM, Tidey JW, Swift RM. Intolerance for Smoking Abstinence Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and relationship to tobacco dependence and abstinence. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th. Pearson Boston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2004;5:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tull MT, Schulzinger D, Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW. Development and initial examination of a brief intervention for heightened anxiety sensitivity among heroin users. Behavior Modification. 2007;31:220–242. doi: 10.1177/0145445506297020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. The Clinical journal of pain. 2008;24:497–508. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vujanovic AA, Bonn-Miller MO, Potter CM, Marshall EC, Zvolensky MJ. An Evaluation of the Relation Between Distress Tolerance and Posttraumatic Stress within a Trauma-Exposed Sample. Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment. 2011;33:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, Benoit C, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Psychiatric history and psychologic adjustment as risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain. The Clinical journal of pain. 2007;23:307–315. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3180330dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Jamison RN. Does report of craving opioid medication predict aberrant drug behavior among chronic pain patients? The Clinical journal of pain. 2009;25:193–198. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318193a6c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, Schieffer B, Pham Q, Baria A, Van Vort W, Davis F, Shekelle P, Naliboff BD. The addiction behaviors checklist: validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2006;32:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, Hogan J, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]