Abstract

The authors examined the association of factors, in addition to prehypertensive office blood pressure (BP) level, that might improve detection of masked hypertension (MH), defined as nonelevated office BP with elevated out‐of‐office BP average, among individuals at otherwise low risk. This sample of 340 untreated adults 30 years and older with average office BP <140/90 mm Hg all had two sets of paired office BP measurements and 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) sessions 1 week apart. Other than BP levels, the only factors that were associated (at P<.10) with MH at both sets were male sex (75% vs 66%) and working outside the home (72% vs 59% for the first set and 71% vs 45% for the second set). Adding these variables to BP level in the model did not appreciably improve detection of MH. No demographic, clinical, or psychosocial measures that improved upon prehypertension as a potential predictor of MH in this sample were found.

Masked hypertension (MH), defined as nonelevated office blood pressure (BP) with elevated average out‐of‐office BP, is associated with cardiovascular risk approaching that of sustained hypertension (BP elevated in office and out of office).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Studies have demonstrated that MH is a reproducible phenotype and that people with BP in the “high‐normal” or upper level prehypertension range are more likely to have MH.6, 7 Detection of MH requires either ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or home BP monitoring to acquire data for calculating out‐of‐office BP average. Given that either method requires resources, including equipment and time, it would be valuable to have a strategy for targeting which patients with a nonelevated office BP should have systematically performed out‐of‐office BP measurements in order to detect MH.

One could posit reasons why BP might be systematically normal inside the office but elevated outside the office. For example, work stress may lead to BP elevations that are actually diminished when one is sitting in a healthcare provider's office.8 Home strain, trait anger, and high stress in general may all act similarly.9, 10, 11 Smoking, which transiently raises BP, may contribute to an elevated out‐of‐office BP average that is not detected in a clinical setting as a result of the time of refraining from a cigarette.12, 13 In one Israeli study, MH was associated with younger age, male sex, and higher awake pulse rate.14 Identification of factors consistently associated with MH would help clinicians decide which patients with a nonelevated office BP should be considered for out‐of‐office BP monitoring.

We previously reported the sensitivity and specificity of prehypertensive office BPs for detecting MH.7 In that study, we noted that while an office BP cutoff of >120/82 mm Hg had the best performance as a screening test for identifying possible MH, it unfortunately had a high false‐positive rate. A risk assessment that uses variables in addition to office BP level might improve prediction and decrease the proportion of people who would be tested by ABPM but are found to have normal ambulatory BP. In this study, we examined the association of several candidate variables with MH and whether any associated variables besides prehypertension improved identification of adults with MH who were not taking BP‐lowering medications.

Methods

Study Recruitment and Setting

We recruited 420 adults via a combination of passive recruitment and active recruitment. For passive recruitment, we posted signs in seven primary care clinics inviting people with a recent office (clinic) BP measurement that was “borderline” or “a little high” to participate. Individuals interested in participating contacted a study coordinator to confirm eligibility and schedule their study visits. For active recruitment, we sent an e‐mail about the study to our campus listserv approximately every 3 to 4 months. Study coordinators also recruited potentially eligible participants via electronic medical records review of vital signs documented during their most recent primary care clinic visit. To be eligible, a person had to be 30 years or older, have a primary care clinician, and not be taking BP‐lowering medications. The participant's most recent clinic visit BP had to be between 120 mm Hg and 149 mm Hg systolic or 80 mm Hg and 95 mm Hg diastolic with neither greater than 149/95 mm Hg. Exclusion criteria included diabetes, pregnancy, dementia, any condition that would preclude wearing an ambulatory BP monitor, and persistent atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmia. As an incentive, participants were offered $150 for completion of the study. All study procedures took place in a clinical research center.

Office BP in the Research Setting

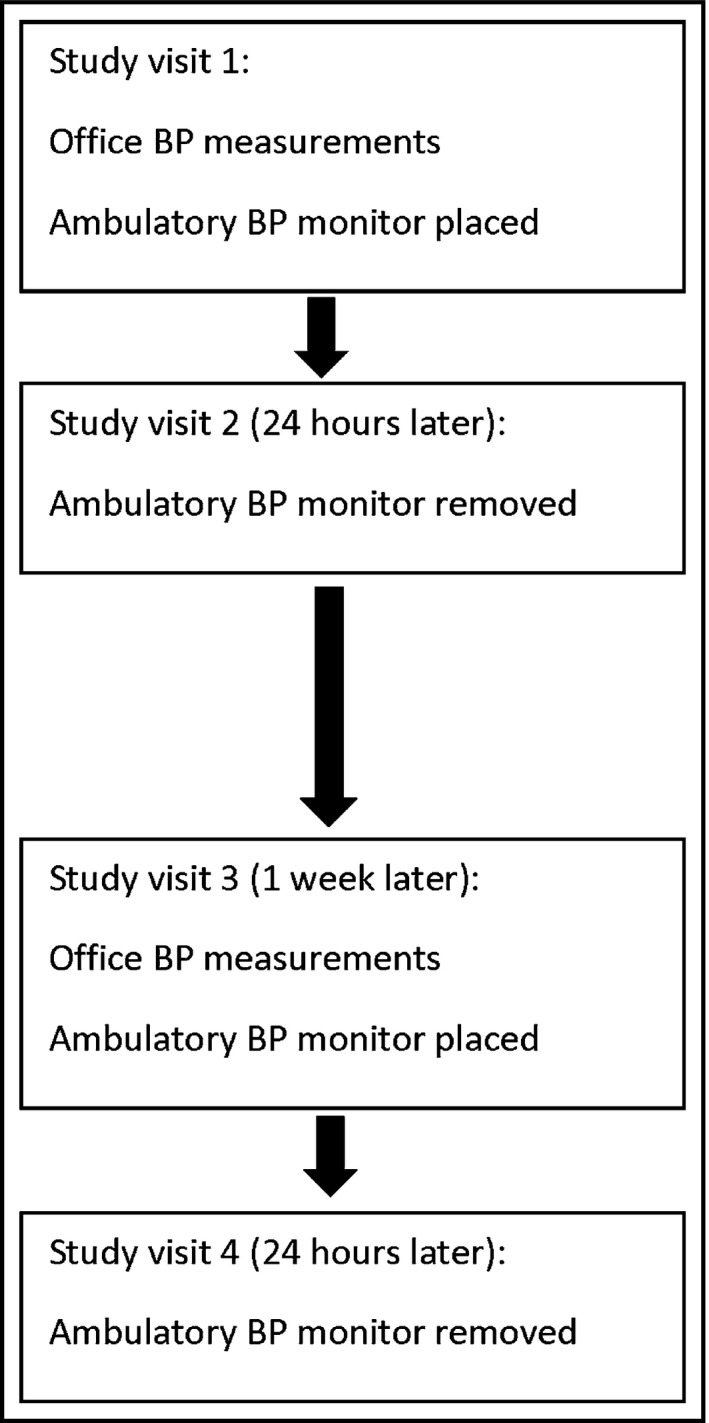

Following check‐in procedures at the four study visits (Figure), participants were placed in an examination room within the clinical research center. After at least a 5‐minute rest, same arm BP was measured three times by a validated office‐type oscillometric device (Welch Allyn Vital Signs15; Welch Allyn Inc, Skaneateles Falls, NY) according to recommended timing and positioning and using the appropriate BP cuff size.16 The three measurements were averaged to determine the participant's office BP measurement for the visit.

Figure 1.

Participant study flow. BP indicates blood pressure.

For this analysis, we excluded participants (n=80) with an initial research office BP average ≥140/90 mm Hg at the first set of measurements, as such participants would either have sustained hypertension or white‐coat hypertension as opposed to MH or sustained normotension.

Ambulatory BP Monitoring

Participants underwent two 24‐hour ABPM sessions 1 week apart using the Oscar 2 oscillometric monitor (Suntech Medical, Morrisville, NC). The Oscar 2 has been validated for use in adults by both the British Hypertension Society protocol and the International Protocol for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices.17, 18 The monitors were programmed to measure BP at 30‐minute intervals from 6 am to 11 pm and at 1‐hour intervals from 11 pm to 6 am. The relaxed intervals were chosen to minimize wearer burden given that we asked participants to wear the BP monitor twice in a short time span. Maximum BP measurement time was limited to less than 140 seconds, and the monitors were set for a maximum pressure of 220 mm Hg. Participants were given verbal instructions on wearing the monitor, including that they should try to leave the cuff on during the entire monitoring period, that they should try to hold their cuffed arm as still as possible during a measurement to ensure that the monitor would get an accurate reading, that cuff inflation would cause a tight feeling around the arm, and that faulty readings would trigger a repeat measurement. The minimum number of readings we accepted as an adequate ABPM session was 14 for daytime and six for nighttime.

Other Variables

Perceived stress was measured using the Perceived Stress Scale.19 Trait anger, trait anxiety, and state anxiety were measured using the Spielberger inventories.20, 21 Job strain was measured using the Karasek Job model,22 and home life stress was measured using the Home Life Pressure Index.23 Height and weight were measured at the first study visit and used to calculate body mass index (BMI). Arm circumference at mid‐biceps was measured at the first study visit and used to guide BP cuff size. Demographics and medical history items were collected by self‐administered questionnaire.

Analysis

MH was defined as a preceding research office BP average <140/90 mm Hg with either a mean 24‐hour ambulatory systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg or mean 24‐hour diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg.24 Normotension was defined as a preceding research office BP average <140/90 mm Hg with both a mean 24‐hour ambulatory systolic BP <130 mm Hg and a mean 24‐hour diastolic BP <80 mm Hg. We examined bivariate associations of several preselected candidate “predictor” variables with MH separately for each session of paired office and ambulatory BP measurements. We modeled the MH status at the two time points simultaneously using the generalized estimating equations method with an exchangeable working matrix to account for dependence between two outcomes. The time factor was not significant in any of the three models and hence was dropped from the final models. Using C statistics with MH based on the first set of measurements as the outcome, we compared a model containing only BP levels to a model containing other variables that were associated with MH at the P<.10 level at both sessions.

Study Approval

This study was approved by the Office of Human Research Ethics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The mean±standard deviation age of the 340 participants included in the analysis was 48 (±12) years. Most participants were between 30 and 44 years (44%) or between 45 and 64 years (44%) (Table 1). A small proportion was older than 65 years (12%). Nearly 60% were female. Three fourths were white and 22% were black. Most were college graduates (64%), and the majority (94%) reported good to excellent health. Most (93%) were also nonsmokers and overweight (32%) or obese (39%). The majority were married or living with a partner. Only three participants did not have sufficient daytime ambulatory BP monitor readings at the first session, and five did not have sufficient daytime ambulatory BP monitor readings at the second session.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=340)

| Characteristic | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | ||

| 30–44 | 151 | 44 |

| 45–64 | 149 | 44 |

| >65 | 40 | 12 |

| Female sex | 199 | 59 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 74 | 22 |

| White | 254 | 75 |

| Other | 12 | 3 |

| Education level | ||

| Some high school | 5 | 1 |

| High school graduate | 16 | 5 |

| Some college | 64 | 19 |

| College graduate | 255 | 75 |

| Work outside home | 263 | 77 |

| Total household income (annual), $ | ||

| <25,000 | 42 | 13 |

| 25,000–50,000 | 68 | 20 |

| >50,000 | 226 | 67 |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | 239 | 71 |

| Public | 45 | 13 |

| Both | 33 | 10 |

| Uninsured | 21 | 6 |

| Self‐reported health | ||

| Excellent/very good | 231 | 68 |

| Good | 90 | 26 |

| Fair or poor | 19 | 6 |

| Nonsmoker | 315 | 93 |

| Drink alcohol | 125 | 56 |

| Caffeine intake >75th percentile | 81 | 24 |

| Married or living with partner | 217 | 64 |

| BMI | ||

| Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 99 | 29 |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | 109 | 32 |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 132 | 39 |

| Resting pulse rate <75 beats per min | 233 | 69 |

| Microalbuminuria | 76 | 23 |

| Office systolic BP at visit 1 | ||

| <120 mm Hg | 94 | 31 |

| 120–130 mm Hg | 125 | 41 |

| 131–139 mm Hg | 87 | 28 |

| Office diastolic BP at visit 1 | ||

| <80 mm Hg | 178 | 56 |

| 80–84 mm Hg | 62 | 20 |

| 85–89 mm Hg | 77 | 24 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Prevalence of MH in the Study Sample

As previously described, the prevalence of MH in the overall study sample was high.25 This high prevalence may have been the result of our method of recruiting people who had a recent “borderline” office BP measurement. When the sample was restricted to only those with prehypertensive research office visit BP average, the prevalence was especially high. Using the office BP average paired with the immediately following ABPM average, the prevalence of MH based on the first sets of measurements was 69.4% (95% confidence interval, 64.1%–74.7%), and the prevalence based on the second sets of measurements was 65.9% (95% confidence interval, 60.5%–71.3%).

Associations With MH

Other than BP level, the only factors that were associated (at P<.10) with MH at both time periods were male sex and working outside the home (Table 2). Using the first set of measurements, 75% of men vs 66% of women had MH. Using the second set, 73% of men vs 61% of women had MH. Among those who worked outside the home, 72% and 71% had MH by the first and second set of measurements vs 59% and 45% among those who did not work outside the home. None of the candidate psychosocial measures we examined appeared to be associated with MH (Table 3). Adding variables to BP level in the model did not appreciably improve detection of MH (Table 4).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations of Participant Characteristics With MH

| Characteristic | Category | Patients With MH at Visit 1, % | P Value | Patients With MH at Visit 2, % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | 30–44 | 71 | .64 | 74 | .029 |

| 45–64 | 69 | 61 | |||

| >65 | 63 | 54 | |||

| Sex | Male | 75 | .09 | 73 | .03 |

| Female | 66 | 61 | |||

| Race | Black | 70 | .95 | 62 | .40 |

| White/other | 69 | 67 | |||

| Education level | <College graduate | 69 | .90 | 63 | .61 |

| College graduate | 70 | 67 | |||

| Work outside home | Yes | 72 | .04 | 71 | .0001 |

| No | 59 | 45 | |||

| Total household income (annual), $ | <25,000 | 75 | .45 | 68 | .91 |

| 25,000–50,000 | 63 | 64 | |||

| >50,000 | 69 | 67 | |||

| Insurance status | Insured (any) | 69 | .41 | 66 | .64 |

| Uninsured | 78 | 60 | |||

| Self‐reported health | Excellent/very good | 70 | .61 | 66 | .91 |

| Good | 66 | 64 | |||

| Fair or poor | 78 | 69 | |||

| Current smoker | Yes | 87 | .06 | 81 | .18 |

| No | 68 | 65 | |||

| Drink alcohol | Yes | 74 | .78 | 65 | .78 |

| No | 72 | 63 | |||

| Caffeine intake | High | 75 | .20 | 73 | .13 |

| Low/moderate | 67 | 64 | |||

| Relationship | Married/living with partner | 69 | .80 | 65 | .58 |

| Single/not living with partner | 70 | 68 | |||

| BMI | Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 70 | .94 | 64 | .45 |

| Overweight (25–29 kg/m2) | 70 | 71 | |||

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 68 | 63 | |||

| Resting pulse rate | <75 beats per min | 66 | .055 | 66 | .87 |

| ≥75 beats per min | 77 | 65 | |||

| Microalbuminuria | Yes | 79 | .055 | 73 | .14 |

| No | 66 | 63 | |||

| Office systolic BP | <120 mm Hg | 47 | <.0001 | 48 | <.0001 |

| 120–130 mm Hg | 82 | 70 | |||

| 131–139 mm Hg | 77 | 83 | |||

| Office diastolic BP | <80 mm Hg | 60 | .0001 | 55 | <.0001 |

| 80–84 mm Hg | 82 | 73 | |||

| 85–89 mm Hg | 83 | 89 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; MH, masked hypertension.

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations of Psychosocial Measures With MH

| Characteristic | Quartile | Patients With MH at Visit 1, % | P Value | Patients With MH at Visit 2, % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State anxiety | 1 | 71 | .83 | 70 | .55 |

| 2 | 68 | 63 | |||

| 3 | 65 | 61 | |||

| 4 | 72 | 70 | |||

| Trait anxiety | 1 | 68 | .97 | 64 | .95 |

| 2 | 71 | 69 | |||

| 3 | 68 | 66 | |||

| 4 | 70 | 65 | |||

| Job strain | 1 | 71 | .77 | 73 | .29 |

| 2 | 67 | 68 | |||

| 3 | 76 | 64 | |||

| 4 | 74 | 79 | |||

| Home life pressure | 1 | 70 | .98 | 69 | .79 |

| 2 | 71 | 66 | |||

| 3 | 68 | 68 | |||

| 4 | 68 | 61 | |||

| Perceived stress | 1 | 62 | .18 | 67 | .36 |

| 2 | 75 | 73 | |||

| 3 | 62 | 60 | |||

| 4 | 72 | 62 | |||

| Trait anger | 1 | 68 | .037 | 58 | .35 |

| 2 | 80 | 72 | |||

| 3 | 67 | 64 | |||

| 4 | 59 | 68 |

Abbreviation: MH, masked hypertension.

Table 4.

Models With Sex and Work Outside the Home Added to Blood Pressure Levels

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Office systolic BP | |||||||||

| <120 mm Hg | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 120–130 mm Hg | 2.2 | 1.4, 3.4 | <.001 | 2.2 | 1.4, 3.3 | <.001 | 2.3 | 1.5, 3.6 | <.001 |

| 131–139 mm Hg | 2.3 | 1.4, 3.7 | <.001 | 2.2 | 1.4, 3.5 | <.001 | 2.4 | 1.5, 3.8 | <.001 |

| Office diastolic BP | |||||||||

| <80 mm Hg | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 80–84 mm Hg | 1.8 | 1.1, 3.0 | .029 | 1.7 | 1.0, 2.9 | .036 | 1.7 | 1.0, 2.9 | .049 |

| 85–89 mm Hg | 2.5 | 1.4, 4.3 | .001 | 2.4 | 1.4, 4.2 | .001 | 2.4 | 1.4, 4.2 | .001 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Female | 0.7 | 0.5, 1.1 | .16 | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.2 | .26 | |||

| Work outside home | |||||||||

| No | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.4 | 1.5, 3.8 | <.001 | ||||||

| C‐statistic | 0.709 | 0.714 | .78* | 0.736 | .26† | ||||

*P value for model 1 and model 2 comparison. † P value for model 2 and model 3 comparison.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to identify factors consistently associated with MH. Identification of such factors would help clinicians decide which patients with a prehypertensive office BP should be considered for out‐of‐office BP monitoring in order to detect MH. We examined several candidate demographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables, but none were strongly associated with MH. The best “predictor” of MH is prehypertensive office BP level.

Other investigators have identified factors associated with MH. Male sex, high pulse rate, and smoking were associated with MH in one Israeli study.14 We did not find high pulse rate or smoking to be associated with MH, but our study had a low prevalence of smokers and our participants also differed in that they were not actually being seen for a clinical visit. We did observe male sex to be associated with MH; however, this is not helpful in improving detection of MH. A different study, conducted in Finland, found older age, higher BMI, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption to be associated with MH.26 Our study did not replicate these findings, but we note that the Finnish study had a much larger sample size (N=1459), which increased its power to find statistically significant associations. A prior study, also with a much larger sample size, found job strain (high demand and high decision latitude) to be associated with MH in a sample of male white collar workers but not among female white collar workers.27

In our study, we noted that simply working outside the home was associated with MH. It is important to acknowledge that guidelines recommend that ABPM be performed on a workday. In previous work, we pointed out that home BP monitoring and ABPM are not interchangeable for detecting MH. The obvious limitation is that home BP measurements are typically only made in the morning and in the evening, periods that may miss times when BP is prone to elevation. It is possible that a home BP monitor taken to work and used in the workplace, or used mid‐day at home, might be able to identify MH. Such a protocol could be tested in further studies.

Prehypertension increases cardiovascular risk compared with optimal BP, but not enough to justify antihypertensive therapy for most patients. It is possible that much of the risk attributable to office prehypertension is actually a reflection of a population in which a large proportion of people have MH. We know from multiple studies that the cardiovascular risk of MH approaches that of sustained hypertension. Thus, ABPM may be useful to risk stratify patients who have prehypertensive office BPs, for whom treatment beyond lifestyle modifications might be considered. It was our hope that additional variables could be used to guide such a strategy, but the BP level itself may indeed be the best clinical indication of potential MH. Further studies are still needed to determine whether treatment of MH, guided by out‐of‐office BP measurements, leads to reduced cardiovascular disease events. The answer may also depend on the natural history of MH, or the time it takes for such patients to “transition” to sustained hypertension. Patients’ acceptance of treatment of MH—when their office BP is “normal”—also needs to be examined.

Streamlining use of ABPM to identify MH is desired because of the costs and the potential discomfort involved. For patients whose office BP is elevated (ie, ≥140/90 mm Hg), ABPM has been shown to be cost‐effective compared with reliance of office BP measurements alone because of its ability to identify white‐coat hypertension, which most evidence suggests needs not be treated.28 Future analyses could also examine the cost of using ABPM among patients whose BP is in the prehypertensive range. Assuming that treatment of MH reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease events, such a strategy might be cost‐effective compared with relying only on office BP measurements and not treating patients with MH.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include its repeated sets of measurements of office and ambulatory BP as well as its measurement of several candidate factors. We also acknowledge several limitations. Our sample may not be representative of a general clinic population, and we did not include patients with diabetes. The sample also had a high prevalence of MH, which may have diminished our ability to identify associated factors. Our sample also had a relatively low prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking, which have been found in other studies to be associated with MH. Finally, there may be factors that are associated with MH that we simply did not measure.

Conclusions

Prehypertensive BP levels are associated with MH. The additional factors examined in this study did not significantly improve ability to discriminate between people more vs less likely to have MH. For now, clinicians and researchers interested in using ABPM to detect MH could consider offering it to patients 30 years and older whose BP is in the prehypertensive range.

Disclosures

Dr Viera has served on the Medical Advisory Board of Suntech Medical, manufacturer of the Oscar 2 ambulatory BP monitor.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01 HL098604 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:784–789. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12761. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

References

- 1. Liu JE, Roman MJ, Pini R, et al. Cardiac and arterial target organ damage in adults with elevated ambulatory and normal office blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sega R, Trocino G, Lanzarotti A, et al. Alterations of cardiac structure in patients with isolated office, ambulatory, or home hypertension: data from the general population (Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni [PAMELA] Study). Circulation. 2001;104:1385–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white‐coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verberk WJ, Kessesl AG, de Leeuw PW. Prevalence, causes, and consequences of masked hypertension: a meta‐analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pierdomenico SD, Pannarle G, Rabbia F, et al. Prognostic relevance of masked hypertension in subjects with prehypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shimbo D, Newman JD, Schwartz J. Masked hypertension and prehypertension: diagnostic overlap and interrelationships with left ventricular mass: the masked hypertension study. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viera AJ, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, et al. Levels of office blood pressure and their operating characteristics for detecting masked hypertension based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindquist TL, Beilin LJ, Knuiman MW. Influence of lifestyle, coping, and job stress on blood pressure in men and women. Hypertension. 1997;29(1Pt1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suls J, Wan CK, Costa PT Jr. Relationship of trait anger to resting blood pressure: a meta‐analysis. Health Psychol. 1995;14:444–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schum JL, Jorgensen RS, Verhaeghen P, et al. Trait anger, anger expression, and ambulatory blood pressure: a meta‐analytic review. J Behav Med. 2003;26:395–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. James GD, Yee LS, Harshfield GA, et al. The influence of happiness, anger, and anxiety on the blood pressure of borderline hypertensives. Psychosom Med. 1986;48:502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Omvik P. How smoking affects blood pressure. Blood Press. 1996;5:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mann SJ, James GD, Wang RS, Pickering TG. Elevation of ambulatory systolic blood pressure in hypertensive smokers. A case‐control study. JAMA. 1991;265:2226–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ben‐Dov IZ, Ben‐Arie L, Mekler J, Bursztyn M. In clinical practice, masked hypertension is as common as isolated clinic hypertension: predominance of younger men. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(5 pt 1):589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones CR, Taylor K, Poston L, Shennan AH. Validation of the Welch Allyn ‘Vital Signs’ oscillometric blood pressure monitor. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones SC, Bilous M, Winship S, et al. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to the International Protocol for the validation of blood pressure measuring devices. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goodwin J, Bilous M, Winship S, et al. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spielberger CD, Jacobs G, Russel S, Crane R. Assessment of Anger: the State‐Trait Anger Scale. In: Butcher JN, Spielberger CD, eds. Advances in Personality Assessment. Vol 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983:161–189. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spielberger CD. Manual for the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karasek R. Job Content Questionnaire and user's guide. Lowell, MA: University of Massachusetts; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grewen KM, Girdler SS, Light KC. Relationship quality: effects on ambulatory blood pressure and negative affect in a biracial sample of men and women. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O'Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G. Ambulatory blood pressure measurement: what is the international consensus? Hypertension. 2013;62:988‐94–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Viera AJ, Lin FC, Tuttle LA, et al. Reproducibility of masked hypertension among adults 30 years or older. Blood Press Monit. 2014;19:208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hänninen MR, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, et al. Determinants of masked hypertension in the general population: the Finn‐Home study. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1880–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trudel X, Brisson C, Milot A. Job strain and masked hypertension. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:786–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lovibond K, Jowett S, Barton P, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modelling study. Lancet. 2011;378:1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]