Introduction

Scapular fractures are relatively rare, constituting 0.4% to 1% of all fractures and 3% to 5% of all shoulder girdle injuries [1]. Displaced fractures of the scapula constitute 6% of these fractures [2]. This may be because scapula is a sturdy and well protected bone. The rarity of scapular fractures speaks of the great force required to disrupt the scapula. They are usually caused due to high energy vehicular trauma or fall from height. Accordingly, there are often associated injuries of the ipsilateral limb, shoulder girdle, cervical spine and thorax. In patients with multiple injuries, scapular fractures are often overlooked or neglected, because of other life threatening injuries requiring urgent attention. In most cases, early functional treatment of scapular fractures produces good to excellent results. The bone is embedded in large muscle masses, so that, when fractures do occur, displacement of the fragment is usually minimal and complete recovery is the rule. It is exceptional for a scapular fracture to require open reduction and operative intervention. It is justified only when bone and soft tissue damage are such that with only conservative measures, function will not be restored and post traumatic osteoarthritis will develop. This report is of a rare case of displaced scapular fracture in a young lady following a road traffic accident, which was managed with closed reduction and immobilisation, which led to satisfactory result.

Case Report

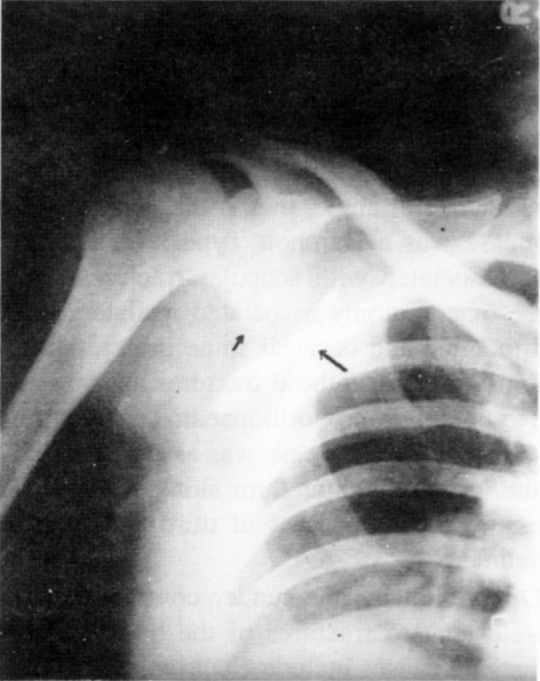

A 27 year old female patient reported to our hospital after being involved in an accident. Patient sustained a direct hit on her right shoulder and fell down. She had complaints of severe pain, inability to move right shoulder and swelling over the upper back. She was not comfortable in supine position. She also had a painful swelling of right elbow. Clinical and radiological examination revealed a grossly displaced fracture of the body of the right scapula (Fig-1), undisplaced fracture of the right capitellum and avulsion fracture of the spinous processes of C3 and C4. There were no other associated injuries. First aid management consisted of immobilisation in a broad arm sling.

Fig. 1.

Antero-posterior radiograph showing displaced scapular body fracture

Patient was taken up for closed reduction under general anaesthesia for her displaced fracture scapula. Reduction was done by abducting the Tight arm and pushing the large displaced fragment of the body into position. This was followed by strapping of scapula to maintain reduction and immobilisation of the right upper limb in a broad arm sling. Satisfactory alignment was confirmed by radiography (Fig-2. She was also given a soft cervical collar and above elbow plaster cast immobilisation for cervical spine injury and fracture of the capitellum. Gradual range of motion exercises of the shoulder and elbow were started four weeks after removing the strapping and above elbow plaster cast. On review after eight weeks, the fracture had united and the patient had attained full range of pain free shoulder movements.

Fig. 2.

Antero-posterior radiograph showing satisfactory reduction

Discussion

Reluctance of the patient to move the shoulder after a high energy trauma, together with pain, tenderness and swelling in the region of scapula, should lead the physician to suspect a fracture of the scapula. However, due to frequent occurrence of associated injuries. this fracture gets overlooked. One third of these injuries are missed on admission [3]. Adequate radiographs of scapula, that is, true anteroposterior and lateral views are essential for accurate diagnosis [2]. In our case the displaced fracture of scapula was clinically obvious.

Scapular fractures have been classified in various ways. The commonest in use is as described by Zdrakovic and Damholt [4]. Type I, fracture of the body or spine of scapula, Type II, fracture of the apophysis i.e. the acromion or the coracoid, Type III, fracture of the superior lateral angle, that is the neck of the glenoid. Our case was a Damholt Type I fracture. Morbidity rates associated with scapular fractures are high because of commonly associated ipsilateral limb injury and thoracic and cervical spine injury. Thus, it is essential to diagnose these fractures as soon as possible and to obtain prompt orthopaedic consultation to minimise morbidity. Our case was associated with fracture of the ipsilateral capitellum along with avulsion fractures of spinous process of third and fourth cervical vertebrae.

Direct violence and sudden contraction of divergent muscles causes fractures of the body of the scapula. Other rare causes include electrical shock causing seizures. Of all scapular fractures, body fractures have increased incidence of associated injuries [5]. It is rare to have a displaced scapular body fracture due to strong muscle mantle around it. But as seen in this case, we can have a grossly displaced body fracture (Fig-3) requiring reduction. As studied in the past, conservative treatment of the scapular fractures gives satisfactory end result in terms of adequate motion, good union, lack of pain and good function of the shoulder [6]. Operative treatment may be rarely required for fracture of the articular surface of the glenoid or double fracture involving neck of the scapula or glenoid and fracture of the clavicle, making the superior suspensory shoulder complex unstable. The best way to manage all other patients, is simple immobilisation, until acute pain has subsided and emphasizing active range of motion exercises as early as possible [7].

Fig. 3.

Line diagram showing the fracture pattern before and after reduction

The aim of presenting this case, is to highlight the occurrence of relatively infrequent case of displaced fracture of scapula. Although grossly displaced fracture of body of scapula is uncommon due to good muscle mantle, it may occur when there is relatively high energy trauma. The management still remains conservative with good functional results.

References

- 1.Hardegger FH, Simpson Lex A, Weber BG. The operative treatment of scapular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66-B:725–730. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6501369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buttress KP. Fractures and dislocations of the scapula. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, editors. Fractures in adults. 4th ed. editors Lippincot Raven publishers; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 1163–1189. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson DA, Flynn TC, Miller PW, Fischer RP. The significance of scapular fractures. J Trauma. 1985;25:974–977. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198510000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zdrarkovic D, Damholt VV. Comminuted and severely displaced fracture of scapula. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;45:60–65. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mc Wilber EB, Evans, Galveston Fractures of the scapula. J Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59-A:358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGahan JP, Rab GT, Dublin A. Fractures of the scapula. J Trauma. 1980;20:880–883. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLennan JG, Ungresma J, Bishop Pneumothorax complicating fracture of scapula. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64-A:665–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]