Highlights

-

•

We studied a CMD patient with structural brain abnormalities.

-

•

Next-generation sequencing identified a reported variant in TMEM5.

-

•

We expanded the spectrum of TMEM5-associated disorders.

Keywords: Congenital muscular dystrophy, TMEM5, Polymicrogyria, Cochlear dysplasia, Limb-girdle muscle weakness

Abstract

The dystroglycanopathies, which are caused by reduced glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan, are a heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by variable brain and skeletal muscle involvement. Recently, mutations in TMEM5 have been described in severe dystroglycanopathies. We present the clinical, molecular and neuroimaging features of an Italian boy who had delayed developmental milestones with mild limb-girdle muscle involvement, bilateral frontotemporal polymicrogyria, moderate intellectual disability, and no cerebellar involvement. He also presented a cochlear dysplasia and harbored a reported mutation (p.A47Rfs*42) in TMEM5, detected using targeted next-generation sequencing. The relatively milder muscular phenotype and associated structural brain abnormalities distinguish this case from previously reported patients with severe dystroglycanopathies and expand the spectrum of TMEM5-associated disorders.

1. Introduction

The dystroglycanopathies are heterogeneous clinical conditions characterized by reduced glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan (α-DG) in skeletal muscles [1]. Clinical presentations range from prenatal brain malformations to congenital muscular dystrophies (CMDs) with various combinations of ocular involvement and mental retardation, and late-onset limb-girdle muscular dystrophies (LGMDs) [1]. The list of disease-associated genes has grown rapidly with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies which can be combined with protein network analysis [2], and this has significantly expanded the spectrum of clinical phenotypes [3].

TMEM5 encodes a transmembrane protein thought to be involved in the glycosylation of dystroglycan [2]. Mutations in TMEM5 were initially described in three infants presenting congenital muscle hypotonia and severe brain malformations meeting the clinical diagnosis of Walker–Warburg syndrome (WWS)/muscle–eye–brain disease (MEB) [2], the most severe, rapidly lethal forms of CMD [1]. A study of an undiagnosed cohort of fetuses with cobblestone type II lissencephaly (cobblestone-LIS) [4], a peculiar brain malformation with characteristic MRI abnormalities, revealed five additional mutations.

We herein expand the phenotypic spectrum of disorders associated with mutations in TMEM5, describing a patient who presented repeatedly elevated CK levels and mild limb-girdle muscular involvement, and whose NGS-based molecular testing disclosed an already reported variant.

2. Case report

This 13-year-old boy was born to non-consanguineous healthy parents at 38 weeks of gestation. At birth he presented with a low birth weight (2600 g), normal head circumference (36 cm) and respiratory distress. His neurodevelopment was globally delayed as he had achieved the sitting position at the age of 8 months and walked unaided at 23 months. A firstEEG recording, ordered by the general pediatrician because of developmental delay at the age of 14 months, showed polymorphic slow waves but no seizures. At the age of 3 years, medical examinations prior to surgery for undescended testis revealed elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels (2054 U/L, normal <190). Despite an improvement in his motor skills, due to speech and psychomotor therapy, the patient underwent a skeletal muscle biopsy at the age of 4 years because of persistently elevated CK levels (3227 U/L) and EMG features suggestive of a myopathy. Histochemistry showed a dystrophic pattern with abnormal variation in fiber size, necrosis and few scattered degenerative fibers, whereas immunofluorescent stains for dystrophin, merosin/laminin-a2 (300 kDa antibody) and sarcoglycans were normal (not shown). The glycosylated forms of α-DG were not analyzed because of lack of material.

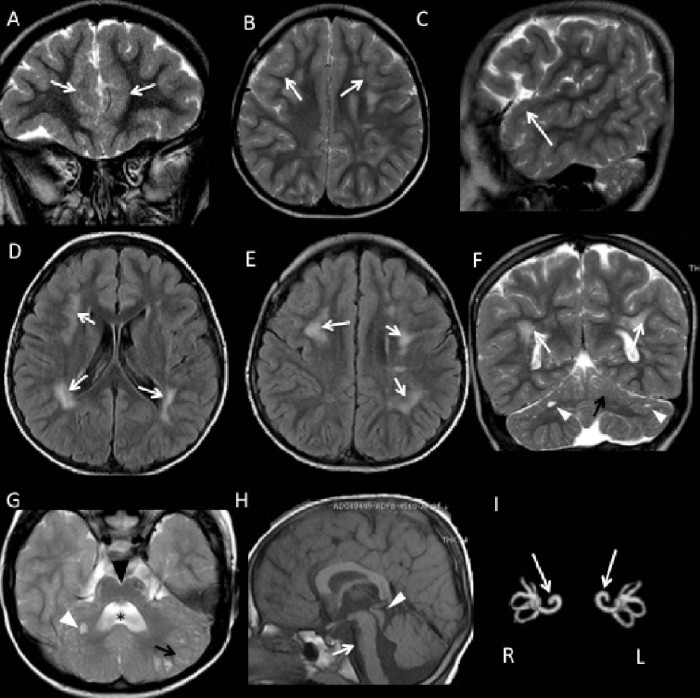

At the age of 5 years – when his weight was 24 kg (97° percentile), height 114 cm (85°), and head circumference 50 cm (50°) – a brain MRI showed bilateral frontotemporal polymicrogyria (Fig. 1A–C), abnormal signals in the frontoparietal white matter bilaterally, with a patchy, confluent appearance (Fig. 1D–F), a dysplastic cerebellar cortex, and small subcortical cerebellar cysts (Fig. 1G). Hypoplasia of the pons with a ventral cleft and a dilated and dysmorphic fourth ventricle (Fig. 1H), and also bilateral cochlear dysplasia (Fig. 1I), were also seen.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI in a patient with CMD carrying a mutation in TMEM5. (A–C) Coronal, axial and sagittal FSE T2-weighted images showing bilateral frontotemporal polymicrogyria (white arrow). (D, E) Axial FLAIR and (F) coronal FSE T2-weighted images revealing patchy, confluent frontoparietal white matter hyperintensities, bilaterally distributed (white arrow). In F as well as in G (axial T2-weighted image) cerebellar anomalies are evident. The latter include abnormal orientation of the cerebellar folia, an irregular gray matter-white matter junction (black arrows) and multiple small subcortical cysts in both cerebellar hemispheres (white arrow heads). In G the cleft in the ventral pons (note the black arrow head) and an enlarged and dysmorphic fourth ventricle (star) are also evident. (H) Sagittal T1-weighted image demonstrating hypoplasia of the pons (white arrow) and a mildly enlarged tectum (white arrow head). (I) Reconstruction of MIP 3D FIESTA image showing bilateral cochlear dysplasia, with fusion of the middle and apical cochlear turns, suggestive of Mondini-type deformity (white arrow). R, right; L, left.

The patient attended yearly neuromuscular follow-ups, and showed a stable clinical course. At the time of latest examination when he was age 13, his growth was normal but he revealed relatively mild symmetric proximal weakness: he was able to walk 10 m in 6 s, to run 10 m in 3.3 s, and to rise from the floor in 12 s. His forced vital capacity was 63% of normal values. Ocular and cardiac evaluations were normal and there were neither gait and trunk ataxia nor dysmetria and nystagmus. Neuropsychological assessment revealed a moderate mental delay with low verbal skills and slight deficits in attention, short term working memory, and problem solving. Consistently with the bilateral cochlear dysplasia observed on neuroimaging, brain auditory evoked potentials revealed mild hearing impairment, especially in the right ear.

This case was included in a group of undiagnosed muscular dystrophy patients to be analyzed by Dystroplex, an extended NGS testing panel able to investigate, in a single tube, the coding regions of 93 genes linked to CMDs, LGMDs or related diseases (see supplementary Appendix). We detected the already described homozygous c.139delG:p.(A47Rfs*42) in TMEM5 [2]. The mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing and found to be heterozygous in the healthy parents. Two additional predicted deleterious variants [the heterozygous c.1654-6A>G in POMT2, described in a child with LGMD and low α-DG [5], and the novel c.1079A>G: p.(Y360C) in DOLK] were also detected in the patient and his father.

3. Discussion

To date, 12 patients harboring mutations in TMEM5 have been described. Two siblings carried the homozygous p.A47Rfs*42 mutation and had severe intellectual disability with autistic features, microcephaly, broad-based gait, 20-fold increased levels of serum CK, and a dystrophic pattern on muscle biopsy. In one case, neuroimaging revealed brainstem atrophy, dilated ventricles, widespread pachygyria and significant white matter changes [2]. A nonsense p.R340* was detected in the same study in an unrelated WWS newborn who had muscle hypotonia, right microphthalmia, bilateral opaque cornea, cranial ultrasound evidence of hydrocephalus, and occipital encephalocele, and died at the age of 22 months [2]. Lastly, nine fetuses in five families with cobblestone-LIS harbored different loss-of-function changes [4].

The present case report lies at the mildest end of the possible spectrum of TMEM5-associated disorders. Unlike previously reported cases carrying p.A47Rfs*42, our patient showed only mildly delayed achievement of motor milestones and neither signs of cerebellar involvement nor microcephaly; furthermore, he presented mild muscular weakness that involved the lower limb-girdle muscles but did not prevent him from running or using a bike, even though he tired quickly. The phenotype appeared severe on brain imaging, yet resulted in only moderate intellectual disability and the boy was able to attend school profitably without needing a support teacher. Our data offer a further example of the value of targeted NGS technologies in clinical settings. The striking differences with earlier TMEM5-related cases provide a further illustration of the fact that clinical presentation in the dystroglycanopathies cannot be explained solely by the specific gene mutation [6]. The question of whether other modifiers of the α-DG glycosylation pathway might have contributed to the milder course seen in our patient remains unanswered.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank EuroBioBank and Telethon Network of Genetic Biobanks (GTB12001H) for providing biological samples. We acknowledge the contribution of Dr Raffaello Canapicchi, who reviewed the MRI data, and Catherine J. Wrenn, who provided expert editorial assistance.

This work was partially funded by Telethon Foundation grants (GUP11001 to FMS; GUP13004 to AD, GA, and LP).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2016.05.003.

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Dystroplex, a targeted NGS gene panel in alpha-dystroglycanopathies.

References

- 1.Muntoni F., Torelli S., Wells D.J., Brown S.C. Muscular dystrophies due to glycosylation defects: diagnosis and therapeutic strategies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:437–442. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834a95e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jae L.T., Raaben M., Riemersma M. Deciphering the glycosylome of dystroglycanopathies using haploid screens for Lassa virus entry. Science. 2013;340:479–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1233675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belaya K., Rodríguez Cruz P.M., Liu W.W. Mutations in GMPPB cause congenital myasthenic syndrome and bridge myasthenic disorders with dystroglycanopathies. Brain. 2015;138:2493–2504. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Bouchet-Seraphin C., Chelbi M. Identification of mutations in TMEM5 and ISPD as a cause of severe cobblestone lissencephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey C., Clement E., Mein R. Refining genotype phenotype correlations in muscular dystrophies with defective glycosylation of dystroglycan. Brain. 2007;130:2725–2735. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercuri E., Muntoni F. The ever-expanding spectrum of congenital muscular dystrophies. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:9–17. doi: 10.1002/ana.23548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dystroplex, a targeted NGS gene panel in alpha-dystroglycanopathies.