Abstract

Vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell anaemia is one of the commonest presentations and a leading cause of death. Death can be sudden and unexpected. Herein we present three cases of sickle cell anaemia with sudden death within 3 days of hospitalisation. All the three cases presented with fever and jaundice. Two cases presented consecutively in the same year within a span of 5 months while the other case had presented 2 years prior to these two cases. Infection was the precipitating event in two cases and pregnancy with infection in one. One case in addition had ‘right upper quadrant syndrome’ and one case had ‘acute chest syndrome’ (ACS) due to bone marrow fat embolism. Postmortem liver biopsy of all the three cases showed dilated and congested sinusoids with sickled RBCs, kupfer cell prominence with erythrophagocytosis. Lung biopsy of case with ACS showed vessels occluded with bone marrow elements indicating bone marrow fat embolism.

Keywords: Sickle cell anaemia, Vaso-occlusive crisis, Sudden death, Bone marrow fat embolism

Introduction

Sickle cell anaemia is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder. The leading causes of death in sickle cell diseases (SCD) are infection, pain episodes, acute chest syndrome and stroke [1, 2]. Death can be sudden and unexpected in sickle cell anaemia [1]. Vaso-occlusive crisis is one of the commonest presentations and a leading cause of death [3]. Herein we present three cases of sickle cell anemia with sudden death within 3 days of hospitalisation, two of which were not known cases of sickle cell anaemia at hospitalization but retrospectively found to have SCD with a positive family history.

Case Report

Two of the cases (Cases 1 and 3) were from Tamil Nadu/Pondicherry region and one case (Case 2) was a migrant labourer from Odisha from a sickle belt region. Cases 1 and 3 presented consecutively in the same year within a span of 5 months while the Case 2 had presented 2 years prior to these two cases.

Clinical Details

Case 1

A 27-year-old female with 8 months of gestation was admitted with a history of fever, jaundice, dysuria, high coloured urine for 4 days. There was no history of itching, clay coloured stools or history of jaundice in the past. On examination, she was pale and icteric. Other systemic examination was normal. She was investigated and managed conservatively. She had an episode of right hypochondriac pain 2 days after hospitalisation. She was referred for obstetrics and gynaecology consultation. Ultrasound and per vaginal examination was consistent with 8 months gestation. But she succumbed to sudden death in the early hours of the third day of her hospitalization.

Case 2

A 23-year-old male, a manual labourer was admitted with high grade fever, myalgia, jaundice, high coloured urine and vomiting. On examination, he was icteric with altered sensorium. Per abdomen examination revealed hepatomegaly 8 cm, tender splenomegaly 4 cm below costal margin. He was on conservative management and investigated. But he died suddenly on day two of hospitalisation.

Case 3

A 28-year-old female, a known case of sickle cell anaemia was admitted for fever and bony pains for 3 days. She developed sudden chest pain, breathlessness and died. She had previous history of jaundice during the ninth month of gestation and found to be sickle cell anaemia on investigations.

Investigations

Biochemical and haematological investigations of all the three cases is summarised in Table 1. Post-mortem tissue samples from liver, bone marrow and lung were examined. Liver biopsy of all the three cases showed dilated and congested sinusoids with sickled RBCs, kupfer cell prominence with erythrophagocytosis and focal hepatocyte necrosis in Case 3 (Fig. 1). Case 1 also showed bone marrow sinusoids studded with sickled RBCs (Fig. 2). Lung biopsy of Case 3 showed vessels occluded with bone marrow elements indicating bone marrow fat embolism (Fig. 3). Haemoglobin (Hb) electrophoresis of Case 3 done previously showed a band in the S, D, G region (Fig. 4) with positive sickling test. For the first two cases, the family history of sickle cell anemia and incomplete details of previous diagnosis were conveyed by the relatives only after demise of the patients. Case 2 in addition was positive for leptospira serology.

Table 1.

Biochemical and haematological parameters in the three cases

| Investigations | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 1 | |

| Sr. bilirubin (mg/dl) | 27.8 | 31.7 | 6.9 | – | 1.7 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 11.2 | 18.4 | 3.5 | – | 0.2 |

| AST (IU/L) | 40 | – | 86 | – | 10 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 73 | 145 | 35 | – | 12 |

| Hemoglobin (g %) | 4.9 | 5.1 | 6 | 4.6 | 6.4 |

| Total leukocyte count (mm3) | 56,400 | 45,000 | 17,800 | 24,700 | 6700 |

| Platelet count (mm3) | 87,000 | 105,000 | 225,000 | 56,000 | 120,000 |

| RBC morphology | Microcytic hypochromic, polychromatophils, few target cells, 25 nRBC/100 WBC | Microcytic hypochromic, moderate anisopoikilocytosis, many target cells, polychromatophils, 30 nRBC/100 WBC, few sickled RBCs | Microcytic hypochromic, moderate anisopoikilocytosis, many target cells, polychromatophils, 60 nRBC/100 WBC, many sickled RBCs | Microcytic hypochromic, moderate anisopoikilocytosis, few target cells, 3 nRBC/100 WBC, few sickled RBCs | |

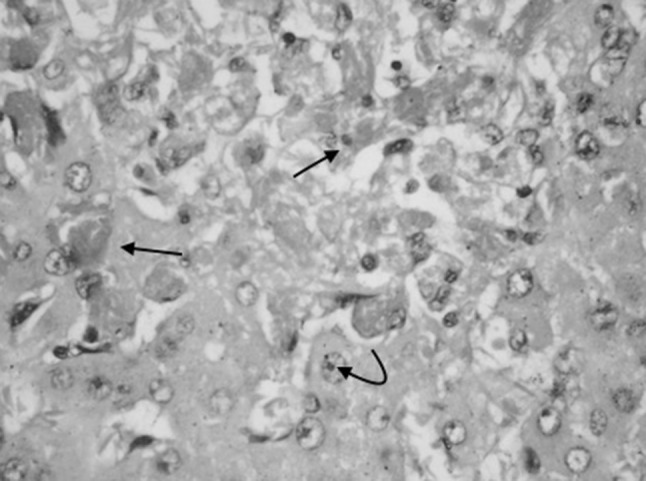

Fig. 1.

Liver biopsy of Case 3 showing dilated, congested sinusoids with sickled RBCs (arrow mark) and hepatocyte necrosis (H&E ×400)

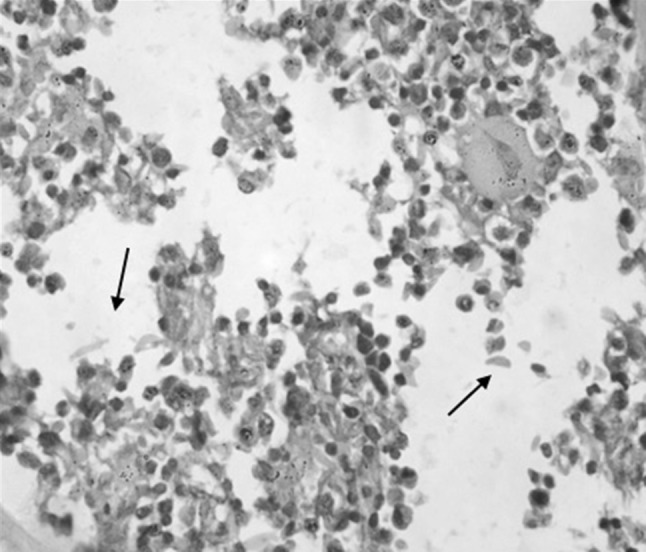

Fig. 2.

Bone marrow biopsy of Case 1 showing normal hematopoietic cells along with sickled RBCs (arrow mark) (H&E ×400)

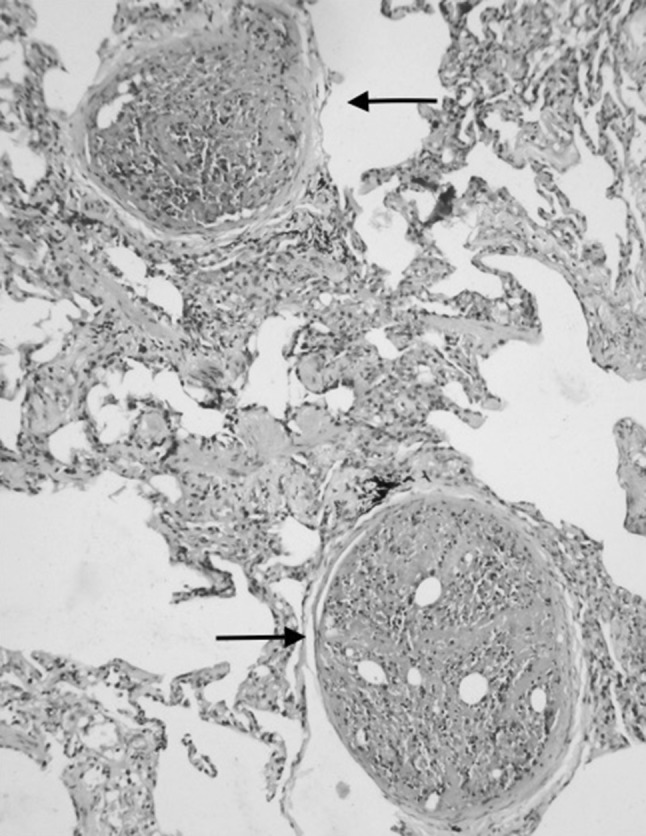

Fig. 3.

Lung biopsy of Case 3 showing bone marrow embolism (arrow mark) (H&E ×200)

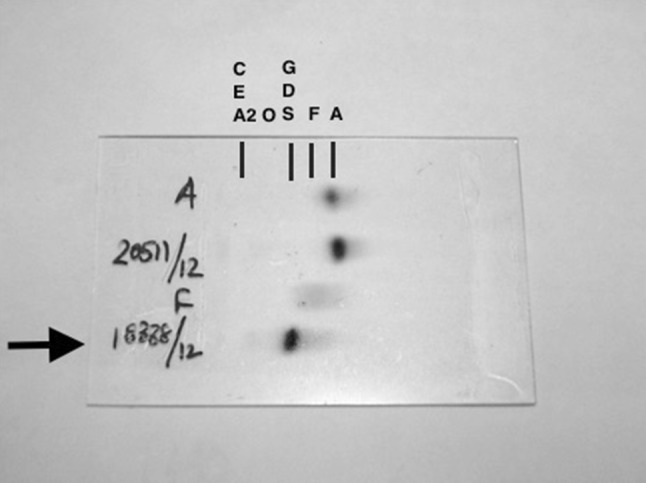

Fig. 4.

Electrophoresis of Case 3 (arrow mark) showing a band in S, D, G region

A final diagnosis of sickle cell anaemia with vaso-occlusive crisis was given in all three cases. The precipitating factors were pregnancy and infection in Case 1 and infection due to leptospira in Case 2. Case 3 in addition to fever had acute chest syndrome (ACS) and showed evidence of bone marrow embolism in lung.

Discussion

Sickle mutation occurs in sixth position of beta chain and encodes valine instead of glutamic acid. This is responsible for changes in molecular stability and solubility. Distortion of cells into sickle shape is due to haemoglobin polymerisation that occurs in deoxygenated state. Kinetics of sickling suggests that polymerisation occurs in stages. The delay period between deoxygenation and polymerisation is attributable to nucleation process. If the delay time is less than 1 s then the RBCs are stuck in the microcirculation resulting in vaso-occlusion crisis. The delay time is strongly influenced by various factors like temperature, pH, Hb concentration, presence of Hb other than HbS [4].

Vaso-occlusive crisis or painful crisis can be precipitated by various factors like infections, low oxygen tension, dehydration, acidosis, extreme physical exercise, physical or psychological stress, pregnancy, alcohol [3, 5].

In Case 1, infection and pregnancy and in Case 2, infection due to leptospira was the precipitating factors. Also Case 1 had an episode of right upper quadrant pain due to vaso-occlusion and acute sequestration of RBCs in the hepatic sinusoids, which is called ‘Right Upper Quadrant Syndrome’. Case 3 presented with ‘Acute chest syndrome’ (ACS) due to fat embolism in the pulmonary vasculature.

ACS is characterised by fever, tachypnea, and chest pain. The leading cause of ACS was infection in children and infarction in adults, but they are often interrelated and concurrent. The causative infectious agents are streptococcus pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Chlamydia, parvovirus B19. Occlusion of pulmonary vasculature is a recognized cause of sudden death resulting from embolization of fat from bone marrow (pulmonary fat emboli) or deep vein thrombosis. Other causes of ACS include asthma, rib infarcts, pleuritis [4].

‘Right Upper Quadrant Syndrome’ characterized by right upper quadrant pain, fever, jaundice, elevated AST/ALT and hepatic enlargement is said to occur in as many as 10 % of patients with acute vaso-occlusive pain [6].

On review of literature, death due to SCD though uncommon is documented. In 1960s SCD was considered a disease of childhood and only few reached adult life. In his autopsy study (1973), Diggs estimated median survival of 14.3 years [7]. Co-operative study of sickle cell disease (CSSD) followed 3764 patients from birth to 66 years of age, at 23 clinical centers throughout United States (1978–1988) and found the median age of death was 42 years for males and 68 years for females. Among 209 deaths, 33 % died during acute sickle crisis (78 % had pain and or acute chest syndrome). Death was sudden and unexpected. Risk factors of early death studied were: seizures, acute anemic episode (30 % decrease in hemoglobin), renal insufficiency (20 % increase in creatinine), pain episodes (clinic visit for pain >2 h) and acute chest syndrome [8]. In an autopsy study, the cause of death was studied in 306 cases of SCD, between 1929 and 1996. The most common cause of death for all Sickle variants and for all age groups was infection (33–48 %). Death was frequently sudden and unexpected (40.8 %) or occurred within 24 h after presentation (28.4 %), and was usually associated with acute events (63.3 %) [1]. In a retrospective study (2011) of five cases that were brought dead to casualty at a centre from India, three had history of acute chest pain. Histopathological examination showed widespread sickling of red blood cells. The diagnosis of sickle cell anaemia was made only after post-mortem examination except for one known case [9].

Maternal mortality which was initially high (33 %) due to painful crisis, acute chest syndrome or pre-eclampsia is much lower now (1.5 %) except for some parts of the world [10].

Conclusion

Sickle cell disease with vaso-occlusive crisis was the cause of death in all the three cases. Death was sudden and unexpected. All the three cases presented with fever and jaundice. Infection was the precipitating event in two cases and pregnancy with infection in one. One case in addition had right upper quadrant syndrome and one case had acute chest syndrome due to bone marrow fat embolism.

Contributor Information

Manickam Niraimathi, Email: niraimathi.md@gmail.com.

Rakhee Kar, Email: drrakheekar@gmail.com, Email: rakhee_kar@rediffmail.com.

Sajini Elizabeth Jacob, Email: jacobsajini6@gmail.com.

Debdatta Basu, Email: ddbasu@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Manci EA, Culberson DE, Yang Y-M, Gardner TM, Powell R, Haynes J, et al. Causes of death in sickle cell disease: an autopsy study. Br J Haematol. 2003;123(2):359–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease—life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yale SH, Nagib N, Guthrie T (2000) Approach to the vaso-occlusive crisis in adults with sickle cell disease. Am Fam Phys 61(5):1349–1356, 1363–1364 [PubMed]

- 4.Wang WC, et al. Sickle cell anemia and other sickling syndromes. In: Greer JP, Foerster J, Rodgers GM, Paraskevas F, Glader B, Arber DA, et al., editors. Wintrobe’s clinical hematology. 12. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 1038–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serjeant GR, Ceulaer CD, Lethbridge R, Morris J, Singhal A, Thomas PW. The painful crisis of homozygous sickle cell disease: clinical features. Br J Haematol. 1994;87(3):586–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb08317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ojuawo A, Adedoyin MA, Fagbule D. Hepatic function tests in children with sickle cell anemia during vaso-occlusive crisis. Cent Afr J Med. 1994;40:342–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diggs LM. Anatomic lesions in sickle cell disease. In: Abramson H, Bertles JF, Wethers DL, editors. Sickle cell disease: diagnosis, management, education, and research. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1973. pp. 189–229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leikin SL, Gallagher D, Kinney TR, Sloane D, Klug P, Rida W. Mortality in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 1989;84:500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanmante RD, Dhumure KS, Sewaimul KD, Chopde SW, Kumbahakarna NR, Bindu RS. Sickle cell disease presenting as sudden death: autopsy findings of five cases. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2011;1(2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogedengbe OK, Akinyanju O. The pattern of sickle cell disease in pregnancy in Lagos, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 1993;12(2):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]