Abstract

Aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is an uncommon, non-neoplastic, expansive and erosive bone lesion. Considered as a pseudocyst due the lack of epithelial lining, the presence of giant cells and similarity to other lesions can make preoperative diagnosis difficult; biopsy findings must be co-related to complete clinical and radiological assessment. ABC’s controversial etiopathogenesis and variable clinicopathological presentations have been widely described, but to date, there are just a few reports in literature describing the development of fibrous dysplasia (FD) from an ABC, and even less cases occurring in the jaws. We describe the case of an ABC in an 8 year-old male patient, affecting the body of the mandible, which showed accelerated growth associated to thinning of the buccal, lingual and lower cortical plates. The treatment consisted of repetitive surgical resection, curettage of the lesion and mandibular reinforcement with osteosynthesis reconstruction plates. A 16-month follow-up showed self-limitation of the overgrowth. The final histopathological and radiological analysis confirmed the FD diagnosis.

Keywords: Aneurysmal bone cyst, Fibrous dysplasia, Jaws

First described by Van Arsdale in 1893 as ossifying hamartoma, but renamed later by Jaffe and Liechtenstein, the aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a non-neoplastic, expansive and erosive bone lesion [1]. Infrequent within the craniofacial skeleton, the ABC was initially described as a long bone and cervical column pathology [2]. In 1958, Bernier and Bhaskar reported the first case occurring on the jaws, and until 2012, only 121 cases were described involving facial bones [3].

The etiopathogenesis of this entity remains controversial, but it has been described as a consequence of traumatism, as hemodynamic alteration, or as a secondary phenomenon associated to the presence of primary bone lesions [4]. It can be classified as primary or secondary, depending on the presence or absence of associated pre-existing histopathological conditions, such as the ossifying fibroma or the central giant cell granuloma, among others, being the first and the most frequently involved [5]. Several articles tried to describe the association between the ABC and the fibrous dysplasia (FD), another type of fibro-osseous lesion; however, cases occurring within the jaws are difficult to find; moreover, the development of a FD from an ABC is even harder to find.

This article presents an extensive mandibular ABC case in a pediatric patient, which followed an unexpected behavior after more than 2 years, 4 interventions, and a 16 month follow-up period. The final histopathologic analysis and its current stabilization (that suggests self-limiting of the growth process) are strongly indicative of FD conversion.

Case Report

An 8-year-old male patient presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgical Service, Clínica SOMECA at Barranquilla, Colombia, with a complaint of asymptomatic swelling on the left side of the lower facial third. His medical history revealed a normal pattern of endocrine function. His surgical history referred to two recent procedures, executed 3 and 4 months before consultation. Before the first surgery, an initial diagnosis of ABC was done, using imaging evaluation with a panoramic X-ray, a computed tomography, an echography and a gadolinium magnetic resonance imaging. Histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis, reason why the first resection of the lesion and bone curettage was performed. The second procedure (due to ABC relapse) was executed 1 month after the first one, and consisted of more aggressive resection and neurovascular decompression of the lesion. The histopathological results this time were the same compared to the first report. One-month postoperative panoramic X-ray and CT scanning showed expansion of the hypodense lesion, cortical perforation and involvement of lower incisive teeth. The MRI showed cystic spaces with internal septa, and fluid–fluid levels of variable intensity. The aggressive recurrence of the lesion was the reason why the patient's mother brought him to our service.

On clinical examination, facial disharmony was evident, due the presence of large ovoid swelling over the left angle and body of the mandible, which caused left hemi-facial contour deformation. The lesion was extended extraorally (Fig. 1). At this time, anatomopathological examination suggested a differential diagnosis between ABC and central giant-cell granuloma, but particular histological and clinical features confirmed the original diagnosis.

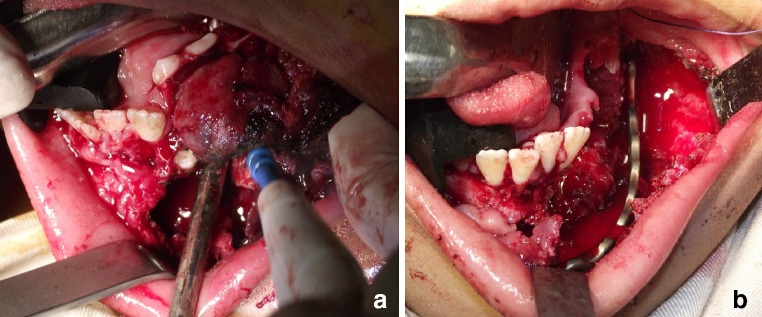

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph of the patient, taken on November 2013, showing facial asymmetry caused by ovoid swelling over the left mandible

At this point, the patient's third surgical procedure in 4 months was executed by the authors of this paper. Under general anesthesia, surgical embolization of the left external carotid artery, and perilesional local anesthetic infiltration, left mandibular vestibular incision was made with electric scalpel, followed by periosteal dissection and soft tissue lesion identification, in order to remove it from the left mandibular body and parasymphysis (Fig. 2a). After this, the involved teeth were extracted and bone curettage was performed. A mandibular reconstruction plate was placed due to bone weakening, using 3 screws on each side (Fig. 2b), followed by Vircyl 3-0® suturing. The histopathologic analysis confirmed the ABC diagnosis (Fig. 3). Five months after the third surgery, the patient assisted to a follow-up appointment with hemifacial contour deformity and intraoral swelling again, suggesting pathology recurrence (Figs. 4, 5). Once more, surgical correction was performed intraorally, but this time, after raising a mucoperiosteal flap over the remnant alveolar ridge, the lesion showed osseous consistency without evidence of soft tissue, and the previously inserted reconstruction plate was almost covered by bone (Fig. 6a). Under general anesthesia, local anesthetic infiltration around the lesion, and lesion exposition by means of a vestibular incision on the mandibular left side was executed. Removal of the excess of bone was performed using Lindemann burs, followed by plate replacement and exodontia of involved teeth. This time, the plate was fixed using 4 screws on the symphysis (Fig. 6b). Vicryl 3-0® suturing was then executed. A new sample was taken for histopathological examination in which FD was finally diagnosed (Fig. 7). Six, twelve and sixteen-month follow-ups showed stability, adequate function and improvement of the facial appearance, due to self-limitation of bone growth (Figs. 8, 9).

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative pictures taken during the third surgery, which was executed on early November 2013. (a) Surgical removal of the lesion (b) Placement of a well contoured mandibular reconstruction plate

Fig. 3.

Histologic image of the third surgery, compatible with ABC diagnosis. H&E 10×. Histologic plate that shows mononuclear fusiform and giant multinucleated cells within hemorrhagic stroma

Fig. 4.

Clinical photograph taken on April 2014, 5 months after the third surgery, showing evident facial asymmetry

Fig. 5.

Panoramic X-ray taken on April 2014, showing mandibular low cortical expansion on the left side, caused by new bone formation around the defect. Multilocular lesions can be observed in left ramus and body of the mandible

Fig. 6.

Picture of the fourth surgical approach executed in early May 2014, showing a bone deposition over the reconstruction plate. b Intra-operative pic that shows the span of the entire new plate from anterior to posterior

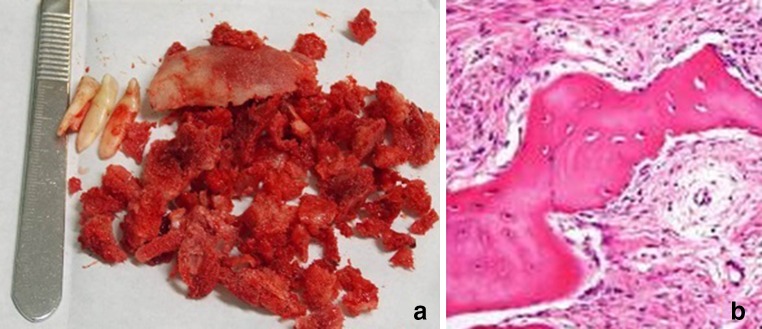

Fig. 7.

a Photograph showing the removed bone and teeth during fourth surgery. b H&E 10×. Histological appearance of the sample, showing bone trabecular calcified tissue, with typical osteocytes, immerse into fibrous stroma

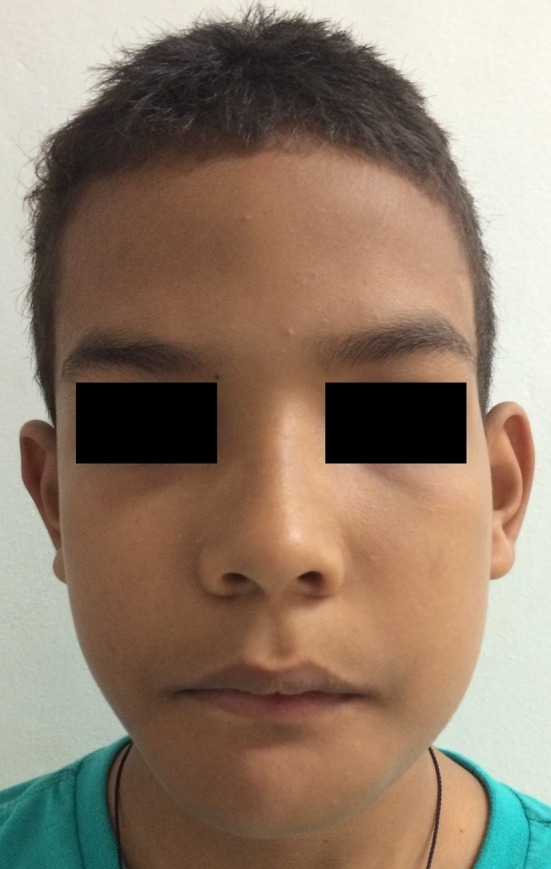

Fig. 8.

Clinical appearance of the patient after 16 months of the last surgery

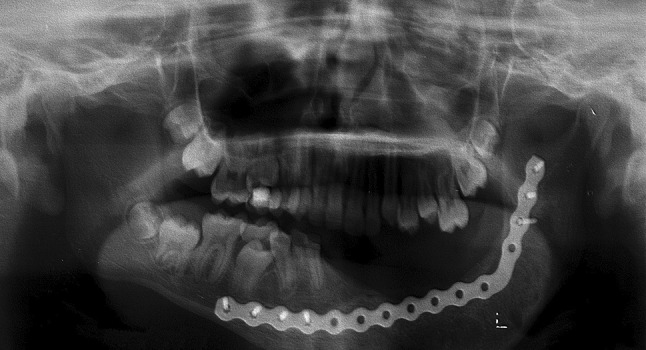

Fig. 9.

Orthopantomogram of the patient after 16 months of the last surgery, showing adequate radiopacity of the left ramus and body of the jaw that suggests bone neoformation

No review of this investigation was needed by the institutional review board, Universidad El Bosque, because the patient identifiers were removed. Informed consent of the patient’s mother was obtained opportunely.

Discussion

The World Health Organization has defined the ABC as an expanding lesion, with blood filled cavities, separated by septa of trabecular bone or fibrous tissue, containing osteoclast giant cells [6]. It is considered as a pseudocyst due the lack of real epithelial lining [7]. Other clinical characteristics are: cortical expansion and erosion, fibro-osseous matrix formation and malignant-like tumor appearance [8]. Clinical diagnosis of ABC is difficult, due to its similarity with other entities such as the ameloblastoma, the central giant cell granuloma, the mixoma, the traumatic bone cyst and the keratocystic odontogenic tumor [9].

The clinical classification of ABC consists of 3 different categories: (1) Conventional or vascular type (95 %) that shows quick and expansive growth which causes cortical perforation, and soft tissue invasion. Histologically, there is multiple sinusoidal spaces filled with blood among fibrous stromal tissue, with multinucleated giant cells, osteoid matrix and hemosiderin presence; (2) Solid type (5 %): first described by Sanerkin in 1983, it is usually discovered during routine X-ray examination, or due to mild asymptomatic swelling. Histological features include hemorrhagic focuses, abundant fibroblastic and fibrohistiocytic elements with osteoclastic giant cells, osteoblastic differentiation zones with osteoid and fibromyxoid calcified tissue; and (3) Mixed type that exhibits both conventional and solid characteristics [10].

In literature, variable presentations of ABC of the jaws were reported by Kalantar et al. [11], in a 51-case series study. As in this case, the majority of cases were diagnosed in males (56.9 %), within the mandibular bone (more than 75 % of the sample), during the first 2 decades of life. The main clinical feature was rapidly growing swelling (92.2 %), with variable radiographic presentation, but always radiolucent. In the same way, all the cases were treated by excision and curettage, and 15.6 % of the cases had recurrences [11]. Buraczewsky and Dabska [12] in 1971 were the first to describe the coexistence of an aneurysmal bone cyst with a fibrous dysplasia (FD). They concluded that it was difficult to establish how often the ABC appears in the course of a FD.

The FD was first described by Jaffe and Lichtenstein [13] in 1942, as a skeletal, self-limiting, and non-malignant fibro-osseous pathology, which shows replacement of bone and marrow by abnormal fibrous tissue. This condition may cause severe craniofacial deformities, affecting one or more bones, and it may cause aesthetic and functional alterations. It has been classified in 2 types (monostotic and polyostotic), depending on the number of affected bones, but recently, a third type has been described as a polyostotic form associated to endocrinopathies [14].

Despite the unclear relationship between these two entities, the literature describes the development of an ABC (or a malignant lesion outbreak) from a previous FD, or the coexistence of both conditions at the same time [15–18]. The cystic degeneration of an FD causing rapid enlargement of FD lesions was documented by Claus-Hermberg et al. occurring in a 15-year old patient in 2011 [19]. In a literature review, Haddad et al. reported 6 cases of concomitant FDs and ABCs of the skull, and described their association as “exceedingly rare” [18]. No reports were found of FDs arising from ABCs.

In this case, the first histologic analysis reported the presence of fusiform mononuclear cell proliferation and multinucleated giant cells within hemorrhagic stroma, without epithelial lining, rounded by septa with fusiform and giant cells, isolated inflammatory cells, and osteoid formation with osteoblastic covering. Trabecular osseous tissue was identified peripherally. These histologic features were consistent with an ABC of conventional type. The radiographic characteristics showing a multilocular osteolytic lesion were also compatible with the diagnosis. After the second surgery, the histopathologic analysis considered two conditions, ABC versus central giant cell granuloma, but specific histological features (as the presence of hemosiderin pigment along with giant cells and abundant fibrous stroma), and other clinical features (as the absence of dental root resorption) supported the original diagnosis. After the third surgery, radiologic changes were evident, and the transformation of the condition was confirmed during the fourth surgery. The abundant sample obtained was histologically analyzed, showing bone trabecular pattern, partially calcified, with typical osteocytes, without osteoblasts, separated by fibrous tissue with elongated nuclei fibroblasts, presence of lymphocytes within hemorrhagic foci, and absence of malignant changes. The lesion conversion was now confirmed, reason why two etiological hypothesis were established: the first hypothesis considers the presence of both conditions simultaneously, followed by activation of an ABC with all the characteristics of the conventional type after the first surgery; the second hypothesis contemplates the development of a monostotic FD directly from the ABC after its removal. The first hypotheses is supported in previous reports in which coexistence of both conditions were reported simultaneously in nine cases, in several anatomic sites distributed as follows: four in the jaws, one in a rib, one in the tibia and three not specified [20–23]. The second hypotheses stands over the “precursor” theory of the aneurysmal bone cyst’s aetiology, in which haemodynamic changes take place in a pre-existing lesion, originating the formation of arteriovenous fistulae, followed by intraosseous increase of vascular pressure and bone expansion [24–27]. In this case however, this conversion theory could be better applied supposing that pre-existing aneurysmal bone cyst-like structures gave origin to hemodynamic changes that gave rise to an expansive development, that activated a fibrous dysplasia, as in the case described by Diercks in 1986 [17]. The dilated vascular bed originated by the modified hemodynamics within the bone (probably caused by tissue injury) could produce erosion, pressure-remodeling, and resorption of surrounding bone, leading to secondary osseous reparative processes, involving multinucleated and acute stromal cells within the vascular structures, accompanied by fibroblastic proliferation, abnormal fibrous tissue and bone formation. The formation of an arteriovenous fistula could supply the osseous tumor blood requirements.

The bone proliferation pattern that followed the third surgery, and the aforementioned test results, give strong arguments to believe that self-limitation of the lesion after a 16-month follow-up period can be definitive; however, the unpredictable behavior and interactions of this kind of conditions reported in literature always demand strict control in the long term.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Jaime Perna and the personnel of the Instituto de Neurociencias Clínica del Sol, Barranquilla. We also want to thank Viviana Bertiller and the Instituto Quirúrgico del Norte for kindly processing and interpreting the histologic plates, and their generous assistance with the histopathologic analysis of this case. For the latter, we also want to thank María Rosa Buenahora, Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia.

References

- 1.Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L. Solitary unicameral bone cyst with emphasis on the roentgen picture, the pathologic appearance and the pathogenesis. Arch Surg. 1942;44:1004–1025. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1942.01210240043003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rai KK, Dharmendrasinh R, Shiva HR. Aneurysmal bone cyst: a lesion of the mandibular condyle. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012;11:238–242. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omami G, Mathew R, Gianoli D, Lurie A. Enormous aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible: and radiologic-pathologic correlation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesecker JL, Marcove RC, Huvos AG, Mike V. Aneurysmal bone cysts. A clinicopathologic study of 66 cases. Cancer. 1970;26:615–625. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197009)26:3<615::AID-CNCR2820260319>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun ZJ, Zhao YF, Yang RL, Zwahlen RA. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the jaws: analysis of 17 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2122–2128. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shear M, Speight P. Cysts of the oral and maxillofacial region. Oxford: Blackwell; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakuma T, Yamamoto N, Onda T, Sugahara K, Yamamoto M, et al. Aneurysmal bone cyst in the mandible: report of 2 cases and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2013;25:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoms.2012.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiattavorncharoen S, Joos U, Brinksschmidt C, Werkmeister R. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible: a case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:419–422. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roychoudhury A, Rustagi A, Bhatt K, Bhutia O, Seith A. Aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible: report of 3 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1996–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalantar MH. Aneurysmal bone cysts of the jaws: clinicopathological features, radiographic evaluation and treatment analysis of 17 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:56–62. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(98)80036-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalantar MH, Navi F, Eshkevari PS, Jafari SM, Shams MG, et al. Variable presentations of aneurysmal bone cysts of the jaws: 51 cases treated during a 30-year period. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:2098–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.05.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buraczewski J, Dabska M. Pathogenesis of aneurysmal bone cyst. Cancer. 1971;28:597–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197109)28:3<597::AID-CNCR2820280311>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenstein L, Jaffe HL. Fibrous dysplasia of bone: a condition affecting one, several or many bones. Arch Pathol. 1942;33:777–816. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:828–835. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadeghi SM, Hosseini SN. Spontaneous conversion of fibrous dysplasia into osteosarcoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:959–961. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31820fe2bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arden RL, Bahu SJ, Lucas DR. Mandibular aneurysmal bone cyst associated with fibrous dysplasia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:153–156. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diercks RL, Sauter AJ, Mallens WM. Aneurysmal bone cyst in association with fibrous dysplasia: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68:144–146. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.68B1.3941131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haddad GF, Hambali F, Mufarrij A, Nassar A, Haddad FS. Concomitant fibrous dysplasia and aneurysmal bone cyst of the skull base. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;28:147–153. doi: 10.1159/000028639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claus-Hermberg H, Lozano MP, Pozzo MJ. Aneurysmal bone cyst in cranial fibrous dysplasia. Bone. 2011;48:S286–S287. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clough JR, Price CHG. Aneurysmal bone cysts: review of 12 cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50:116–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buraczewski J, Dabska M. Pathogenesis of aneurysmal bone cyst: relationship between aneurysmal bone cyst and fibrous dysplasia of bone. Cancer. 1971;28:597–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197109)28:3<597::AID-CNCR2820280311>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaffe HL (1962) Discussion on Donaldson’s paper. J Bone Joint Surg 44-A:25–40

- 23.Dabska M, Buraczewski J. On malignant transformation in fibrous dysplasia of bone. Oncology. 1972;26:369–383. doi: 10.1159/000224688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffe HL. Aneurysmal bone cyst. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 1950;1950(11):3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtenstein L. Aneurysmal bone cyst: a pathological entity commonly mistaken for giant-cell tumour and occasionally for hemangioma and osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1950;3:279–289. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:2<279::AID-CNCR2820030209>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein L. Aneurysmal bone cyst: further observations. Cancer. 1953;6:1228–1237. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195311)6:6<1228::AID-CNCR2820060617>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson WF (1962) Aneurysmal bone cyst. J Bone Joint Surg 44-A:25–39