Abstract

Chronic protracted dislocation of the TMJ is a relatively uncommon but extremely unpleasant and distressing condition for a patient. It is also particularly challenging and difficult to treat as it worsens with time due to continuing spasm of the masticatory muscles and progressive fibrosis, adhesions and consolidation in and around the dislocated joint. No definite guidelines or treatment protocols have been laid down in literature till date, towards management of such dislocations. A range of extensive and invasive surgical procedures such as eminectomy, condylectomy, menisectomy, and various osteotomies of the mandibular ramus and body have been performed to reduce these dislocations. A chronic longstanding unilateral TMJ dislocation in a 64-year-old woman was managed successfully and effectively using a modified, rather conservative surgical technique. The aim was to reduce the dislocated condyle (without excessive manipulation of the intra-articular space or extra-articular joint components); and at the same time, to limit further excessive translation of the condyle and restore physiological TMJ biomechanical constraints, to prevent future recurrence. This was achieved by surgically exposing the dislocated joint and manipulating the anterosuperiorly positioned condyle back into the glenoid fossa, aided by a downward distraction of the mandible; followed by soft tissue tethering of the meniscus and fibrous capsule of the joint to the temporal fascia above. The procedure yielded excellent results without any functional limitations or recurrence, and can hence constitute a viable and effective treatment option which can be attempted prior to resorting to the more invasive surgical procedures as described in literature.

Keywords: Acute TMJ dislocation, Chronic protracted/persistent dislocation (CPD), Chronic recurrent dislocation (CRD), Meniscal plication, Capsular plication

Introduction

Dislocation of the TMJ represents 3 % of all reported dislocated joints in the body [1]. TMJ dislocation is mainly of 3 different types—Acute, Chronic recurrent and Chronic persistent/protracted/longstanding [1, 2]. Acute TMJ dislocation is a condition in which there occurs a complete loss of articular relationships, between the articular fossa of the temporal bone and the condyle-disc complex. The condyle is suddenly displaced from the glenoid fossa, moves beyond, usually anterosuperior, to the articular eminence, with a complete separation of the articular surfaces of the joint and fixation of the condyle in that abnormal position, where it is held by spasm of the muscles of mastication. When this occurs, the patient requires medical assistance to reduce the condyle back into the glenoid fossa [2, 3]. Anterior luxation of mandible is normally bilateral and symptoms include inability to close the mouth, mentalis protrusion, tension and spasms of masticatory muscles, excessive salivation and drooling [4]. The facial profile changes while the ligaments around the joint often stretch with intra-articular effusion, causing severe pain, discomfort and difficulty in phonation and mastication [5].

Acute TMJ dislocation may be brought on spontaneously by excessive mouth opening during everyday activities, such as yawning, laughing, taking a large bite or during vomiting [6, 7]. Predisposing factors include dysfunction of components of the TMJ, anatomical abnormality of the articular eminence, glenoid fossa, or condylar head, laxity or flaccidity of the ligaments and the TMJ capsule or dysfunction of the muscles of mastication. Acute dislocation of the TMJ may also be induced by trauma [8–11] forceful mouth opening from dental procedures, endotracheal intubation with laryngeal mask or tracheal tube [12–14]. The term “acute” refers to untreated dislocation up to 72 h from the time since it got dislocated [5, 15].

“Chronic recurrent dislocation” (CRD) of the TMJ is characterized by a condyle that slides over the articular eminence catches briefly beyond the eminence and then returns to the fossa. Most patients find that they can reduce their condyle to the normal position. Recurrent dislocation could result from a variety of causes including TMJ ligament laxity, lack of teeth, shallow glenoid fossa, flat articular eminence, flat or short condyle, muscular spasm and rarely Marfan’s and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [16].

Acute dislocation presenting within 2 weeks is readily reducible by the Hippocratic maneuver [5]. After 2 weeks, spasms and shortening of the temporalis and masseter muscles occur and reduction becomes difficult to achieve manually. This leads to the commencement of “Chronic Protracted Dislocation (CPD)” [17]. The dislocation is maintained by muscle spasm secondary to painful stimuli arising from the capsule. Formation of a new pseudo-joint in the dislocated position sets in allowing varying degrees of mandibular movement. Such patients have difficulty in closing the mouth (open lock) and deranged occlusion in which there is prognathism of the mandible with anterior cross bite [17]. Chronic, protracted dislocation may be left unperceived, undiagnosed/misdiagnosed and untreated for days, weeks, months to even years and develops into a “long standing” condition. This condition is more difficult to treat due to the fibrous adhesions that develop between the joint disc, condyle and articular eminence. Fibrosis and adhesions of retrodiscal tissues, posterior band and posterior bilaminar zone further prevents reduction of the condyle back into the glenoid fossa. Jaw muscles and ligaments may also undergo fibrous changes.

The various methods of managing the chronic protracted TMJ dislocation that have been employed in the past include manual reduction under general anesthesia, external elastic traction with arch bars and elastic bands; assisted open reduction with Bristow’s elevator [18]; Condylectomy [19], Condylotomy, Eminectomy, Vertical-oblique [20] or inverted L ramus osteotomy, sagittal split osteotomy [21] and midline Mandibulotomy [22].

We present a relatively less invasive surgical technique that involves a minimalistic manipulation of the intra- and extra-articular joint components, at the same time, effecting a successful reduction of the dislocated condyle to its proper position and further, affording long term stability to the joint by harnessing its own morphological and anatomical characteristics and accentuating and embellishing its physiological constraints.

Case Report

A 64 year old female patient reported with the complaints of deviation of her lower jaw to the left, an inability to close her teeth together, inability to bite or chew food and a dull persistent pain just ahead of her right ear for the past 3 months. History revealed that 3 months earlier, she had heard a loud snap from her right jaw joint while yawning. Following this incident, she was unable to occlude her teeth together and her jaw had begun deviating to the left side on opening and closing her mouth. She also complained of severe pain in the region of her right jaw joint when she tried to swing her lower jaw to the right side in an attempt to occlude her teeth properly. Clinical evaluation revealed that the patient had an anterior open bite and a left lateral cross bite, with deviation of the mandibular as well as dental midline to the left by 1.5 cm (Fig. 1a, b, g). This had also resulted in a moderate facial asymmetry (Fig. 1a) and a prognathic facial profile (Fig. 1d). She was partially edentulous with a number of missing posterior teeth on both sides. Maximum interincisal mouth opening was 41 mm (Fig. 1c, h) and mouth opening and closing movements were unrestricted, although the mandible perpetually remained deviated to the left. Condylar movements were palpable on the left but not on the right side. There was a notable pre-auricular depression/hollowing in the region of the right temporomandibular joint fossa, just in front of the tragus, and the condyle was palpable 3–4 cm in front of this depression. There was pain and tenderness on palpation of the right TMJ region.

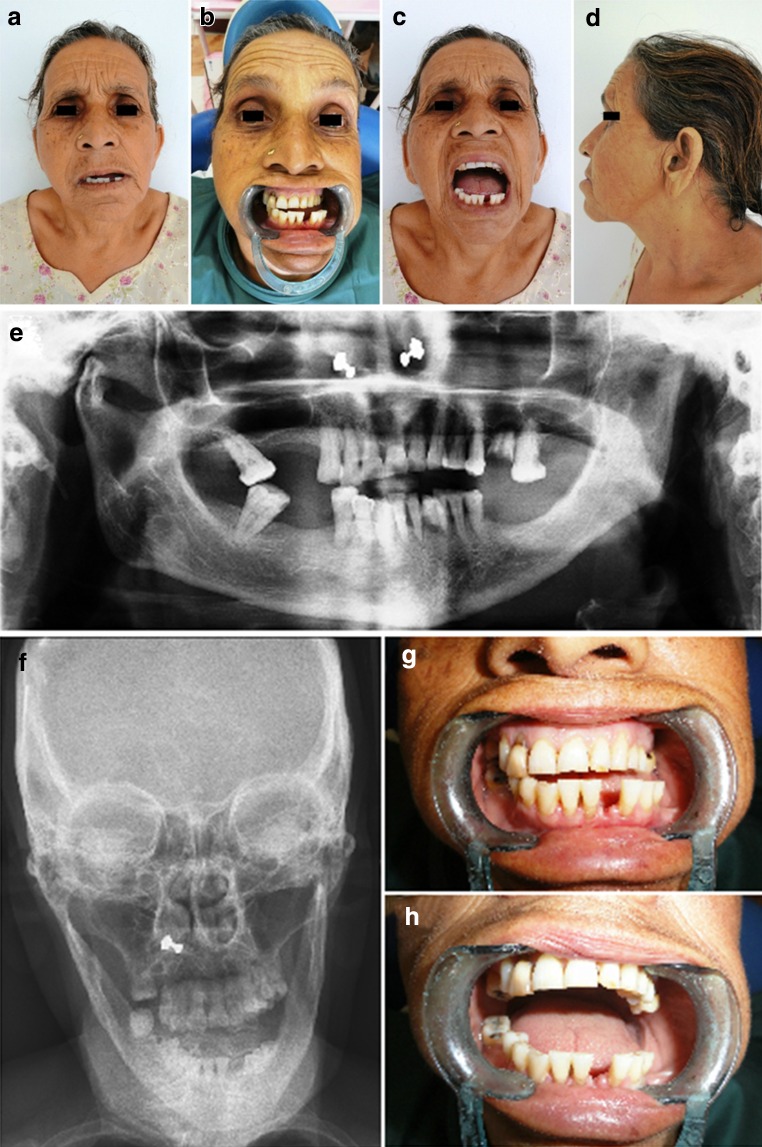

Fig. 1.

a, b A 64 year old female patient with deviation of the mandible to the left, inability to occlude, an anterior open bite and left lateral cross bite. c Unrestricted mouth opening and closing, with the dislocated mandible deviating to the left. d A prognathic appearance of the profile. e OPG showing unilateral dislocation of the right malformed condyle out of the glenoid fossa and high up anterior to the articular eminence. f PA view skull demonstrating the mandibular asymmetry and deviation to the left, with the right condyle more anteriorly positioned than the left. g, h Mandibular dental midline deviation to the left on both closed and open mouth positions

The orthopantomogram revealed a unilateral dislocation of the right condyle out of the glenoid fossa (Fig. 1e). The head of condyle was high up in front of the base of the articular eminence. Also, the right condyle appeared to be malformed, with the condylar head twisted and bent forward at an abnormal angle to the condylar neck. The left condyle, although not dislocated, was much smaller than normal. The articular eminence on the right was steep and elongated. Postero-anterior view of the mandible (Fig. 1f) clearly demonstrated the mandibular deviation to the left. The right condyle appeared much larger than the left and its image was much clearer than the left, because of it being closer to the X-ray film, confirming that it was more anteriorly positioned than the latter. 3-D Computed Tomographic scans (Fig. 2a–c, f, g) clearly showed the dislocation of the misshapen and malformed right condyle anterosuperior to the steep articular eminence. It was positioned within the infratemporal fossa and lay in contact with the medial aspect of the zygomatic arch ahead of the anterior slope of the articular eminence. The right styloid process appeared abnormally long (Fig. 2a, f, g). The left condyle was small and hypoplastic and lay within the glenoid fossa, positioned somewhat medially against the posterior slope of the articular eminence (Fig. 2d, e, h).

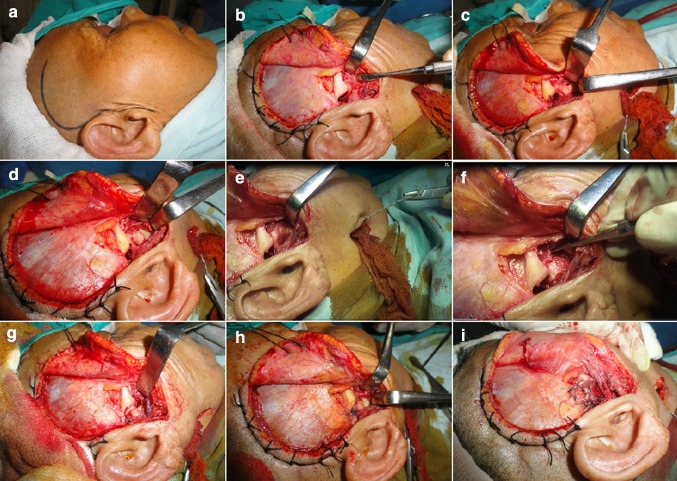

Fig. 2.

3-D CT scans showing dislocation of the misshapen and malformed right condyle antero-superior to the steep articular eminence. The condyle lay in the infratemporal region, in contact with the medial aspect of the zygomatic arch, ahead of the anterior slope of the articular eminence. The right styloid process appeared abnormally long. The left condyle was small and hypoplastic and lay within the glenoid fossa, positioned somewhat medially against the posterior slope of the articular eminence

Correlating the clinical and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of Chronic Protracted Unilateral Right sided TMJ Dislocation was arrived at, which was probably brought on by an excessive mouth opening while yawning 3 months ago. This acute episode had been left undiagnosed and untreated and had thereby turned chronic as a result of muscle spasm and fibrous adhesions in and around the dislocated joint. A pseudo-arthrosis of the right TMJ had developed anterior to the articular eminence, and mouth opening and closing movements continued unrestricted.

The initial attempt at manual reduction of the dislocated right condyle was unsuccessful. Consequently, local anesthetic was injected into the joint, around the capsule, and into the lateral pterygoid, temporalis, and masseter muscle insertions. Manual reduction was attempted again, but was unsuccessful. The contralateral side was then anesthetized, but further attempts at reduction were not successful. The patient was then sedated with Demerol and Diazepam, but reduction could still not be achieved. Under general anesthesia with deep muscle relaxation, further attempts at closed reduction using considerable force were undertaken without success. Finally, surgical exposure of the right TMJ was found necessary.

The right TMJ was exposed to direct vision using Popowich and Krane’s modification of the traditional Al Quayat and Bramley’s modified pre-auricular approach (Fig. 3a, b). It was observed that the mandibular condyle had developed a pseudo-articulation anterior to the articular eminence of the temporal bone, which was enveloped by dense fibrous connective tissue (Fig. 3b). The fibrous tissue was excised, a slit made through the fibrous capsule of the joint, exposing the dislocated malformed condyle (Fig. 3c) and the pseudo-articulation was disengaged. The condyle was manipulated out from the infratemporal fossa, at the same time, maintaining a downward traction on the right angle of the mandible through which a hole was drilled in which was threaded a braided wire (Fig. 3d, e). The condyle was then carefully and gently maneuvered to its normal position within the glenoid fossa (Fig. 3f, g). Now, the lateral margin of the cartilaginous portion of the articular disc was grasped using a delicate toothed dissecting forceps, adhesions were released by gently moving the disc back and forth, and then the meniscus was repositioned as posteriorly as was possible. A suture was drawn through the lateral edge of the meniscus, which was then tethered to the temporal fascia above and posteriorly, thus completing the Meniscal plication (Fig. 3h). The lateral ligament and fibrous capsule too were carefully and tightly tethered to the temporalis muscle and fascia above using vicryl 2-0 sutures, in this way achieving capsular plication as well (Fig. 3i) The intra-articular joint compartment was not violated much and neither were the bony joint components altered during the surgical procedure, thus making the procedure minimally invasive.

Fig. 3.

a Popowich and Crane’s modification of the Alkayat & Bramley’s preauricular incision line. b Exposure of the right TMJ region showing an empty glenoid fossa with dislocation of the entire condyle-disc complex anterior to the articular eminence. c, d Slit made through the lateral aspect of the fibrous capsule, exposing the articular disc and condylar head. e Braided wire threaded through a hole drilled in the right angle of the mandible, used to exert a downward traction, distracting the dislocated condyle below the steep articular eminence. f, g Condyle being manipulated and maneuvered back into place within the glenoid fossa. h Meniscal plication carried out by suturing the lateral edge of the cartilaginous disc to the temporal fascia above and posteriorly. i Capsular plication completed after closing the fibrous capsule, suturing it to the temporal fascia and temporalis muscle above

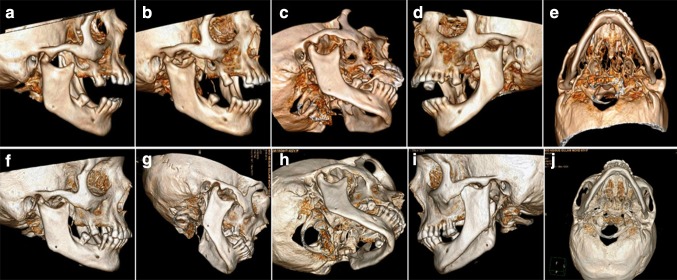

Because of the patient’s frail condition and numerous missing teeth, maxillo-mandibular fixation (MMF) was not applied post operatively. Nevertheless, recovery was smooth and uneventful and she was able to return to her usual diet by the second day, with no recurrence of the dislocation. Postoperative CT Scans confirmed a successful reduction of the dislocated right TMJ (Fig. 4), correction of the mandibular deviation and achievement of normal occlusion. The joint remained stable even in the wide open mouth position as evidenced by the 3-D CT Scans (Fig. 4a–d). The elongated styloid process on the right and partly ossified stylomandibular ligament on the left could be clearly visualized as well (Fig. 4g–j).

Fig. 4.

Postoperative 3-D CT scans showing a successful reduction of the unilateral right TMJ dislocation, with achievement of mandibular symmetry on both a–d open mouth and e–h closed mouth positions and correction of the deranged occlusion. The elongated right styloid process is apparent, with its tip lying just medial to the angle of the mandible

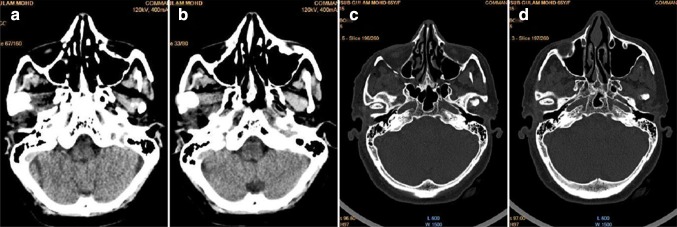

A comparison was made of the right condylar position on axial sections of CT scans taken (Fig. 5a, b) before surgery showing the condyle out of the glenoid fossa and lying impinging the medial aspect of the zygomatic arch in the infratemporal fossa; and (Fig. 5c, d) after surgery, showing successful repositioning of the condyle achieved back within the glenoid fossa.

Fig. 5.

A comparison of the right condylar positions on axial sections of CT scans taken a, b before surgery showing the condyle out of the glenoid fossa and lying impinging the medial aspect of the zygomatic arch in the infratemporal fossa; and c, d after surgery, showing successful repositioning of the condyle achieved back within the glenoid fossa

There was a successful restoration of the patient’s facial and mandibular symmetry, occlusion and masticatory efficiency, with correction of the anterior open and left lateral crossbite (Fig. 6a–d). The operated site healed well with an inconspicuous scar and with no early complications such as facial nerve deficit, Frey’s syndrome, salivary fistula, or late complications such as degenerative joint changes or recurrence of dislocation during the entire follow up period of 14 months.

Fig. 6.

Post operative appearance of the patient with successful correction of the facial asymmetry, occlusal derangement, mandibular and dental midline deviation and prognathic facial appearance

Discussion

The stability of any joint depends on three factors—the integrity of its capsule and ligaments, neuromuscular mechanism of the joint function and bony architecture of the joint surfaces [23]. The mechanism of temporomandibular joint dislocation varies depending on the type of dislocation which may be acute, chronic protracted or chronic recurrent. The capsule of the joint is the most important structure which stabilizes the joint, reinforced by the lateral ligament and supported by the accessory (Stylomandibular and Sphenomandibular) ligaments [24, 25]. In an edentulous patient, since, by definition, there is no opposing dentition, the mandible may become hypermobile and over close. If over closure is not corrected with prosthetic dentures, the TMJ capsule and lateral ligament can permanently stretch and loosen, weakening it, making it lax and flaccid, which can predispose to joint dislocation when force is placed on the mandible or upon excessive or wide opening of the mouth (yawning, in this case) [24]. Displacement of the head of the condyle out of the glenoid fossa is also greatly influenced by the morphology of the condyle, glenoid fossa, articular eminence (atrophied or elongated), zygomatic arch and squamotympanic fissure [26, 27]. In addition to the afore-mentioned factors, age, dentition disharmony of the chewing surfaces of the teeth, internal derangement of the TMJ and masticatory muscle dysfunction also contribute significantly to the mechanism and management of temporomandibular joint dislocation [27].

This was a rare case of a unilateral longstanding luxation of the right condyle out of the glenoid fossa and well ahead of the articular eminence, which on 3-D CT Scans, was found to be extremely steep. The condition had probably originated as an acute bilateral TMJ dislocation resulting from wide opening of the mouth while yawning, which took place 3 months ago. The loud snap on the right was probably due to the dislocation/luxation of the right condyle out of the glenoid fossa, down the slope of the steep articular eminence and then suddenly ahead and superior to it. It is likely that the TMJ dislocation was caused by a combination of overstretched and loose capsular and supporting ligaments (secondary to a perpetual over closure of the mouth brought about due to loss of vertical dimension owing to the partially edentulous condition of the patient), which permitted the excessive anterior translation of the condyle, which itself being malformed, was anatomically susceptible to slide down the posterior slope of the articular eminence and slip out of the glenoid fossa. The spasm of the masticatory muscles and the steepness of the elongated articular eminence on the right side as well as subsequent adhesions, fibrosis and consolidation in and around the dislocated joint and its capsule contributed to inability of the condyle to be reduced spontaneously back into place either by the patient’s own efforts or by the surgeon’s attempts at manual reduction and other conservative measures, manipulation and maneuvers. The deformity of the condyle too, whose head was bent anteriorly, probably contributed to its dislocation and also made it anatomically difficult to reduce. It is further suggested that the elongated styloid process on the right and partially ossified Stylomandibular ligament on the left probably served as predisposing factors too. It is likely that the short Stylomandibular ligament on the right (from near the tip of the process, inserting into the angle of the mandible) failed to support the mandible adequately and did not rein it in and restrict its excessive opening, the vector of the ligament being more horizontal (the tip of the styloid being at the same level as and just medial and adjacent to the angle of the mandible), rather than being posterosuperior to it as is normal.

The grossly hypoplastic condyle on the left must also have dislocated easily at the time of the acute episode, but being underdeveloped and small, was able to slide back and resume its normal position in the glenoid fossa, resulting in a unilateral right sided dislocation. A pseudo-arthrosis developed on the right side, anterior to the articular eminence, which permitted an almost normal range of opening and closing of the mouth, but with mandibular deviation to the left, a deranged bite and inability to occlude and chew.

Treatment of chronic protracted TMJ subluxation includes both conservative as well as surgical methods, though the former are usually unsuccessful [27, 28]. Terakoda et al. [28] described a conservative treatment of chronic mandibular dislocation with the help of intermaxillary fixation screws and elastic traction. Conservative methods like elastic rubber traction with arch bars and ligature wires/IMF with elastic bands are of limited use in achieving reduction in chronic protracted dislocation. Prior to the use of elastic bands, acrylic blocks or impression compound spacers can be placed in between upper and lower teeth to depress the mandible and open up the bite posteriorly, this helps displace the condyle downwards, the elastic bands that are applied front backwards helps to push the mandible/condyle backwards into the fossa after removing the spacer in about 72 h–1 week. Botulinum toxin A injection along with intermaxillary fixation screw has been reported successful in reduction of chronic dislocation [29]. This has a role in a broad range of neuromuscular disorders that cause dislocation of mandible.

Rowe and Killey (1968) described use of a bone hook passed over the sigmoid notch, via a small incision below the angle and a subperiosteal tunnel, so as to exert a downward traction on the condyle; and Mc Graw (1899) used a bone hook over the coronoid process [30–32]. Lewis [33] described the use of a Bristow’s elevator through the temporal fascia in the same manner which it is employed for the Gillies technique of elevation of the depressed zygomatic bone or arch. The tip of the elevator is directed posteriorly to contact the anterior aspect of the dislocated condyle and strong force is then exerted in a downward and posterior direction. This is the assisted reduction under general anesthesia. El-Attar and Ord [34] reduced an old bilateral dislocation by traction hooks inserted into bur holes in the angle of the mandible.

Conservative measures often fail, in which case, many surgical procedures have been undertaken in the past with varying success, including operating on the masticatory muscles, the articular capsule, the articular meniscus, the articular eminence, the zygomatic arch, the mandibular ramus, body, coronoid process and the condyle. When surgery is indicated for chronic protracted/prolonged dislocation (CPD) especially in cases of longer duration, the goal is firstly, to reposition the condyle back in the glenoid fossa and restore movement; secondly, set back the protruded mandible and correct occlusion; and thirdly, employ suitable measures to prevent recurrence. When the temporalis muscle is short and spastic, Laskin [35] has advocated a temporalis myotomy via an intraoral surgical approach using a coronoid incision. Where access is difficult, or when there is fibrosis or adhesion of the muscle and in cases where reunion/reattachment of the muscle may occur, coronoidotomy with or without condylotomy is advocated [31]. Meniscoplasties and menisectomies are relevant procedures which are performed when altered disc morphology and position cause dislocation (“Open Lock” conditions) or prevent self reduction. Total joint replacements are considered when all appropriate treatments fail in chronic protracted and chronic recurrent dislocations, especially those with associated degenerative joint diseases.

At present, the most widely accepted surgical techniques are those used on the articular eminence. It may be reduced (eminectomy), favoring free movement of the condyles [36]. Eminectomy removes the bony obstacle, preventing condylar locking making the joint a self-reducing one, but, does not address the uncoordinated muscle activity and the lax capsule or ligament [37]. Alternatively, an obstacle may be interposed to prevent excessive excursion and anterior translation and movement of the condyles. These techniques include Norman’s procedure of glenotemporal osteotomy with interpositional bone grafting [38, 39] and the Dautrey’s procedure [40, 41, 42] in which the downfractured zygomatic arch is maneuvered inferior to the articular eminences, thus increasing its height. Nonetheless, a number of potential complications have been associated with such techniques, among which are the recurrence of dislocation through a gap within the medial part of the articular eminence, graft resorption, fracture of the distal part of the zygomatic arch, the negative remodeling of both the zygomatic arch, and the articular eminence [43]. Revington [44] reported a failed case when a small condylar head continued to move past the augmented articular eminence via a gap on its medial aspect.

Articular eminence augmentation procedures such as the Dautrey’s or Norman’s techniques, had they been performed in the case presented, would have most likely failed due to the malformed and distorted morphology of the condyles, particularly on the left side as the condyle was severely hypoplastic with a medio-lateral dimension of just 9 mm, which would have slid medial to the augmented articular eminence. Dautrey’s procedure would have most likely have been followed by internal displacement and re-dislocation of the small mandibular condyle because of the limited cross-section of the lateromedial zygomatic arch. Also the advanced age of this patient would have increased the risk of fracture of the distal end of the arch as bone elasticity decreases and brittleness increases as age advances [41].

In the case presented, after manipulating the dislocated condyle back to its correct anatomical position within the glenoid fossa, capsular plication was also carried out in conjunction with an additional measure, namely, meniscal tethering. The lateral edge/periphery of the cartilaginous articular disc was sutured to the temporal fascia and temporalis muscle above and behind, thus restricting the disc’s mobility and tendency to slip forward on excessive mouth opening, which indirectly served as a restraint to the excessive forward translation of the condyle. Fibers of the superior belly of the Lateral Pterygoid muscle insert into the anterior band of the articular disc. The forward pull by the muscle upon mouth opening, together with the laxity of the hitherto chronically stretched retrodiscal tissues (superior and inferior retrodiscal laminae), contribute towards making the disc vulnerable to anterior displacement, following reduction of the chronically dislocated joint. Stabilizing this articular disc by means of tethering it to the temporal fascia, over and above capsular plication, doubly ensures preventing this from happening post-surgery.

The surgical procedure employed was effective and successful in spite of being quick and conservative. Jaw motion parameters were maintained well over the entire follow-up period of 14 months, and radiological assessments showed no signs of any joint pathology or recurrence of dislocation thereafter.

Conclusion

A successful and effective treatment for a patient with chronic longstanding dislocation of the TMJ entails, in addition to repositioning the dislocated condyle back to its normal position, securing sufficient volume of mouth opening, making the joint function normally, and preventing future re-dislocation of the joint. In the case presented, after all non-surgical measures failed, a conservative surgical technique was carried out, in which the chronically dislocated right condyle was surgically exposed and successfully maneuvered into its correct position aided by a downward distraction of the mandible using a braided wire threaded through a hole drilled through the angle of the mandible. Following this, capsular plication as well as meniscal tethering to the temporal fascia and temporalis muscle above and posteriorly were carried out, to prevent future recurrence. Excessive violation of the intra-articular joint space as well as bony joint components such as the condyle, articular tubercle, root of zygomatic arch, glenoid fossa etc. were avoided, thus making the surgery quick and conservative.

The procedure proved effective and yielded excellent post operative results with no recurrences of the dislocation or any immediate or late complications such as restricted mouth opening, pain, clicking or degenerative changes of the joint, Frey’s syndrome, salivary fistula or facial nerve paralysis during a follow up period of 14 months. In this way it could serve as a viable treatment option having many potential advantages as compared to other more extensive and invasive surgical procedures usually employed in such conditions, such as myotomy, eminectomy, condylectomy or articular eminence height augmentation by grafting.

The more complex and invasive methods of treatment may not necessarily offer the best option and outcome; therefore it is proposed that this approach may be attempted before adopting the more invasive surgical techniques, however the same needs to be investigated further with longer post-op follow-up and possibly a bigger sample size.

References

- 1.Lovely FW, Copeland RA. Reduction eminoplasty for chronic recurrent luxation of the temporomandibular joint. J Can Dent Assoc. 1981;3:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talley RL, Murphy GJ, Smith SD, Baylin MA, Haden JL. Standards for the history, examination, diagnosis, and treatment of temporomandibular disorders (TMD): a position paper. American Academy of Head, Neck and Facial Pain. Cranio. 1990;8(1):60–77. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1990.11678302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luyk NH, Larsen PE. The diagnosis and treatment of the dislocated mandible. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(3):329–335. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudreau RG, Tidemann H. Treatment of chronic mandibular dislocation. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41:169–173. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas ATS, Wong TW, Lau CC. A case series of closed reduction for acute temporomandibular joint dislocation by a new approach. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:72–75. doi: 10.1097/01.mej.0000192046.19977.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avidan A. Dislocation of the mandible due to forceful yawning during induction with propofol. J Clin Anaesth. 2002;14:159–160. doi: 10.1016/S0952-8180(01)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesfaya Y, Skorzewska A, Lal S. Hazard of yawning. CMAJ. 1991;14:156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone KC, Humphries RL. Maxillofacial and head trauma. Mandible fractures. Current diagnosis & treatment emergency medicine. 6. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harstall R, Gratz KW, Zwahlen RA. Mandibular condyle dislocation into the middle cranial fossa: a case report and review of literature. J Trauma. 2005;59(6):1495–1503. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199241.49446.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gassner R, Tuli T, Hachl O, Rudisch A, Ulmer H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9,543 cases with 21,067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(02)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoard MA, Tadje JP, Gampper TJ, Edlich RF. Traumatic chronic TMJ dislocation: report of an unusual case and discussion of management. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1998;4(4):44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhandari S, Swain M, Dewoolkar LV. Temporomandibular joint dislocation after laryngeal mask airway insertion. Internet J Anaesthesiol. 2008;16(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sia Swee-Leong, Chang Yin-Lung, Lee Tsang-Mu, Lai Yu-Yung. Temporomandibular joint dislocation after laryngeal mask airway insertion. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2008;46(2):82–85. doi: 10.1016/S1875-4597(08)60032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosis M, Lazar S. Jaw dislocation during general anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34:407–408. doi: 10.1007/BF03010145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sensoz O, Ustûner ET, Celebioglu S, Mutaf M. Eminectomy for the treatment of chronic subluxation and recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint and a new method of patient evaluation. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;29(4):299–302. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato J, Suzuki T, Fujimura K. Clinical evaluation of arthroscopic eminoplasty for the habitual dislocation of the temporomandibular joint: comparative study with conventional open eminectomy. J Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:390–395. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kai S, Kai H, Nakayama E. Clinical symptoms of open lock position of the condyle. Relation to anterior dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90372-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis JES. A simple technique for long-standing dislocation of the mandible. BJOMS. 1981;19:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(81)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Chul-Hwan, Kim Dae-Hyun. Chronic dislocation of temporomandibular joint persisting for 6 months: a case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;38:305–309. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2012.38.5.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debnath SC, Kotrashetti SM. Bilateral vertical-oblique osteotomy of ramus (external approach) for treatment of a long-standing dislocation of the temporomandibular joint: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e79–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adekeye EO. Inverted L shaped osteotomy for prolonged bilateral dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Surg. 1976;41:563–576. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90308-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SH. Reduction of prolonged bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation by midline mandibulotomy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:1054–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shorey CW, Campbell JH. Dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:662–668. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.106693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dimitroulis G. The use of dermis grafts after discectomy for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(2):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Güven O. Review of inappropriate treatments in temporomandibular joint chronic recurrent dislocation: presenting three particular cases. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(3):449–452. doi: 10.1097/01.SCS.0000147389.06617.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipp M, Von Domarus H, Daublender M. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction after endotracheal intubation. Anaesthesist. 1987;36:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasconcelos BC, Porto GG, Neto JP, Vasconcelos CF. Review treatment of chronic mandibular dislocations by eminectomy: follow-up of 10 cases and literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14(11):e593–e596. doi: 10.4317/medoral.14.e593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terakado N, et al. Conservative treatment of prolonged bilateral mandibular dislocation with the help of intermaxillary fixation screw. BJOMS. 2004;44:62–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller Tara D, Neuhaus Isaac M, Zachary Christopher. Botulinum toxin type A for treating temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;21(2):104–106. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe NL, William JLI (1994) Maxillofacial injuries. In: Williams JLI (ed) Chapter 14, injuries of the condylar and coronoid process, 2nd edn, vol 1. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh London, Madrid Melbourne, New York and Tokyo, pp 421–422

- 31.Caminiti MF, Weinberg S. Review chronic mandibular dislocation: the role of non-surgical and surgical treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998;64(7):484–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shakya S, Ongole R, Sumanth KN, Denny CE. Chronic bilateral dislocation of temporomandibular joint. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2010;8:251–256. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v8i2.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JES. A simple technique for reduction of longstanding dislocation of mandible. Br J Oral Surg. 1981;19:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(81)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.EL-Attar A, Ord RA. Long standing mandibular dislocation: report of a case, review of literature. Br Dent J. 1986;160:91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laskin DM. Myotomy for the management of recurrent and protracted mandibular dislocation. Trans Int Conf Oral Surg. 1973;4:264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helman J, Laufer D, Minkov B, Gutman D. Eminectomy as surgical treatment for chronic mandibular dislocations. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;47:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Güven O. A clinical study on treatment of temporomandibular joint chronic recurrent dislocation by a modified eminoplasty technique. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(5):1275–1280. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31818437b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Norman JE (1984) B. Recurrent dislocation of the temporomandibular joint. Glenotemporal osteotomy and a modified dowel graft. European Association for Maxillofacial Surgery, 7th congress. Abstracts 97

- 39.Medra AM, Mahrous AM. Glenotemporal osteotomy and bone grafting in the management of chronic recurrent dislocation and hypermobility of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dautrey J. Surgery of the temporomandibular joint. Acta Stomatol Belg. 1975;72:577–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawlor MG. Recurrent dislocation of the mandible: treatment of ten cases by the Dautrey procedure. Br J Oral Surg. 1982;20:14–21. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(82)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadre KS, Kaul D. Dautrey’s procedure in treatment of recurrent dislocation of the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2021–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.To EW. A complication of the Dautrey procedure. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:100–101. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90091-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Revington PJD. The Dautrey procedure—a case for reassessment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:217. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]