Abstract

Background

Hepatic-artery and para-aortic lymph node metastases (LNM) may be detected during surgical exploration for pancreatic (PDAC) or periampullary cancer. Some surgeons will continue the resection while others abort the exploration.

Methods

A systematic search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library for studies investigating survival in patients with intra-operatively detected hepatic-artery or para-aortic LNM. Survival was stratified for node positive (N1) disease.

Results

After screening 3088 studies, 13 studies with 2045 patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy were included. No study reported survival data after detection of LNM and aborted surgical exploration. In 110 patients with hepatic-artery LNM, median survival ranged between 7 and 17 months. Estimated pooled mean survival in 84 patients with hepatic-artery LNM was 15 [95%CI 12–18] months (13 months in PDAC), compared to 19 [16–22] months in 270 patients with N1-disease without hepatic-artery LNM (p = 0.020). In 192 patients with para-aortic LNM, median survival ranged between 5 and 32 months. Estimated pooled mean survival in 169 patients with para-aortic LNM was 13 [8–17] months (11 months in PDAC), compared to 17 (6–27) months in 506 patients with N1-disease without para-aortic LNM (p < 0.001). Data on the impact of (neo)adjuvant therapy on survival were lacking.

Conclusion

Survival after pancreatoduodenectomy in patients with intra-operatively detected hepatic-artery and especially para-aortic LNM is inferior to patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy with other N1 disease. It remains unclear what the consequence of this should be since data on (neo-)adjuvant therapy and survival after aborted exploration are lacking.

Introduction

Pancreatic and periampullary cancer remain a deadly disease. Five-year survival rates are as low as 5%.1, 2 In pancreatic cancer, forty percent of patients present with locally advanced disease, with an overall survival following palliative chemotherapy of 10 months.3, 4 In those patients with metastatic disease survival (7 months) is even shorter.5 Surgery is feasible in 20% of patients, and following adjuvant chemotherapy may achieve a 5-year survival rate of 20%.6 Following resection of periampullary cancer, 5-year survival may reach 20–50%.7 As such, currently the best survival rates are achieved with resection, and adjuvant chemotherapy. As operative techniques and peri-operative outcomes continue to improve, optimizing the eligibility criteria for resection is of great interest.6, 8 Furthermore, due to limited survival times, identifying those patients who do not benefit from a resection is equally important.

Lymph node metastases (LNM) are regarded as a strong negative prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer, and most studies have focused on the hepatic-artery (station 8a) and para-aortic (station 16b1) lymph nodes. In most centers, patients with preoperatively detected extra-regional LNM do not undergo resection.9, 10 A standard lymphadenectomy, which includes the hepatic-artery but not para-aortic lymph nodes, was recently defined by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS).11 As pre-operative imaging is often not reliable to exclude LNM, intraoperative detection of extra-regional LNM regularly confronts surgeons with the decision to abort the exploration or continue with resection.12 The primary aim of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine survival after pancreatoduodenectomy or aborted exploration in patients with intra-operatively detected hepatic-artery and para-aortic LNM in pancreatic and periampullary cancer. The secondary aim of this study was to compare survival between patients with hepatic-artery or para-aortic LNM versus other N1 disease.

Methods

Study selection

A systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.13 Two systematic literature searches were performed in PubMed, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library up to October 15th, 2015. A clinical librarian checked the searches. The first search identified articles investigating the prognostic impact of LNM in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer. The second search identified articles investigating the prognostic impact of LNM in patients in whom surgical exploration was aborted after detection of LNM. Two independent reviewers (LB and PN for the first search, LB and NCM for the second search) screened title and abstract for eligibility. Discrepancies were solved through discussion and consensus, and in case of any doubt resolved with the senior author. Next, the eligibility of full text articles was assessed similarly. References of finally included articles were checked manually for studies that had not been identified in the primary search.

Study eligibility and outcomes

Studies investigating the prognostic value of LNM on overall survival in patients with pancreatic cancer were considered eligible. From studies of patients undergoing resection, only patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy were included. Reviews, case reports and editorials were excluded. Study and baseline characteristics, LNM location and survival outcomes were obtained.

LNM-specific data were analyzed if in total, there were at least 75 node positive patients per lymph node station involved. This was an arbitrary cut-off, chosen to obtain sufficient data for a robust analysis. Attention was paid to the characteristics of the control group; whether they consisted of node negative (N0) patients or patients with node positive (N1) disease, but negative to the specific lymph node station being analyzed.

Assessment of methodological quality

Methodological quality was assessed using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence.14 Risk of bias in each of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies.15 The criteria for ‘comparability’ in the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale to assess varieties within the arranged cohort was used for a complete analysis.

Statistical analysis

To perform a meta-analysis, using the random effects model, pooled mean survival was estimated using a validated and widely used formula.16 This formula estimates the mean, variance and standard deviation of a sample using the reported sample size, median and range. If not reported, median survival and ranges were deducted from Kaplan–Meier curves. In these cases, if patients were alive at last follow-up, the maximum range was set at the time of censoring. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I-squared statistic considering the following margins: low (0–40%), moderate (30–60%), substantial (60–90%) and considerable (75–100%) heterogeneity. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration) version 5.3.17 Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sensitivity analysis was performed for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) only.

Results

Study selection

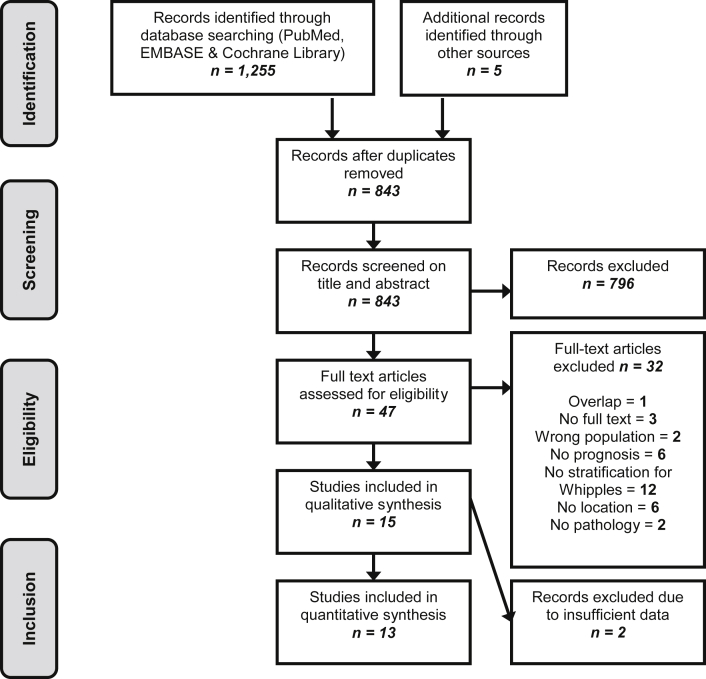

A total of 3088 articles were screened (first search 1255 articles, second search 2097 articles). The PRISMA flowchart for study selection regarding the first search (i.e. patients receiving resection) is shown in Fig. 1. The second search, despite extensive screening, revealed not a single study fulfilling the eligibility criteria. Finally in 13 full text articles were included a total of 2045 patients receiving pancreatoduodenectomy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included studies.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 One study was excluded due to overlap in its patient population with another study assessing additionally extra-regional LNM.29, 30 No studies were excluded due to inadequate methodological quality (Supplementary Table).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Reference and year | Study design | No. PD | Cancer location | JPS lymph node station(s) | Lymph node resection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andersen et al. (1994)18 | Prospective cohort | 117 | PDAC + periampullary cancer | 16 | Unknown |

| 2 | Connor et al. (2004)19 | Prospective cohort | 121 | PDAC + periampullary cancer | 8a and 16b1 | Routine |

| 3 | Cordera et al. (2007)20 | Retrospective cohort | 175 | Pancreatic head cancer | 8 and peripancreatic | On indication, reason unknown |

| 4 | Doi et al. (2007)21 | Retrospective cohort | 133 | PDAC | 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16a2, 16b1, 17, 18 | Routine |

| 5 | LaFemina et al. (2013)22 | Retrospective cohort | 147 | PDAC | 8a and peripancreatic | On indication, per surgeon preference |

| 6 | Massucco et al. (2009)23 | Prospective cohort | 77 | PDAC | 6, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 16 and 17 | On indication, reason unknown |

| 7 | Nappo et al. (2015)31 | Prospective cohort study | 135 | PDAC + periampullary cancer | 16 | Routine |

| 8 | Paiella et al. (2015)29 | Retrospective cohort | 67 | PDAC | 8, 12, 13, 14, 16 and 17 | On indication, per surgeon preference |

| 9 | Philips et al. (2014)24 | Prospective cohort | 420 | PDAC | 8a and peripancreatic | unclear |

| 10 | Sakai et al. (2005)25 | Retrospective cohort | 178 | PDAC | 8 | Routine |

| 11 | Schwarz et al. (2014)26 | Prospective cohort | 111 | Pancreatic head cancer | 16 | Routine |

| 12 | Shrikhande et al. (2007)27 | Retrospective cohort | 29 | PDAC | 16 | On indication, reason unknown |

| 13 | Yamada et al. (2009)28 | Retrospective cohort | 335 | Pancreatic head cancer | 16 | Routine |

PD, pancreatoduodenectomy; JPS, Japanese Pancreas Society; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Hepatic-artery LNM (station 8a)

Survival data related to hepatic-artery LNM in patients receiving pancreatoduodenectomy are given in Table 2. In total there were 539 patients; 110 (20%) patients with and 429 (80%) patients without hepatic-artery LNM. Median survival of patients with hepatic-artery LNM ranged between 7 and 17 months and 3-year survival was 0% in one study among 17 patients. In patients with N1-disease but without hepatic-artery LNM, median survival ranged from 16 to 21 months and 3-year survival was 23% among 60 patients in one study.25

Table 2.

Survival related to hepatic-artery lymph node status

| Study | (neo)Adjuvant therapy (n/N) | Hepatic-artery LNM | Percentage of patients (N) | Survival rate |

Median survival (months) | P-valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 2 y | 3 y | 5 y | ||||||

| Cordera et al. (2007)20 | Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation | Yes | 26% (10) | 0% | 15 | 0.05 | |||

| No | 74% (28) | 17% | 16 | ||||||

| LaFemina et al. (2013)22 | 10/147 neo-adjuvant. | Yes | 21% (23) | 13 | 0.10 | ||||

| No | 79% (86) | 17 | |||||||

| Paiella et al. 201529 | NR | Yes | 13% (9) | 0% | NR | N/A | |||

| No | 87% (58) | 18.3% | NR | ||||||

| Philips et al. (2014)24 | 17/41 adjuvant | Yes | 20% (38) | 17 | 0.659 | ||||

| 56/156 adjuvant | No | 80% (156) | 21 | ||||||

| Sakai et al. (2005)25 | NR | Yes | 22% (17) | 29% | 6% | 0% | NR | N/A | |

| Noa | 78% (60) | 57% | 32% | 23% | NR | ||||

| Connor et al. (2004)19 | 3/13 adjuvant | Yes | 32% (13) | 0% | 7 | 0.037 | |||

| 9/39 adjuvant | Nob | 68% (41) | 15 | ||||||

NR, not reported; N/A, not applicable.

The assessed metastatic lymph node station was compared to N0 patients.

The assessed metastatic lymph node station was compared to N1/8a- and N0 patients together, instead of N1/8a-only.

P-value for difference in median survival.

Estimated pooled mean survival was 15 [95%CI 12–18] months in 84 patients with hepatic-artery LNM compared to 19 [16–22] months in 270 patients with N1-disease without hepatic-artery LNM. Estimated pooled mean difference could be generated from 3 studies and was 3 [95%CI 0–5, p = 0.020] months. There was low statistical heterogeneity among these 3 pooled studies (I2 = 0%, p = 0.5).

Para-aortic LNM (station 16b1)

Survival data related to para-aortic LNM in patients receiving pancreatoduodenectomy are presented in Table 3. In total there were 794 patients; 192 (24%) patients with and 602 (76%) patients without para-aortic LNM. Median survival of patients with para-aortic LNM ranged between 5 and 32 months and 3-year survival ranged between 0 and 3%, although the latter was deducted from 53 patients in two studies only. In patients with N1-disease but without para-aortic LNM median survival ranged between 13 and 34 months and 3-year survival was only reported in one study: 12% in 84 patients.25

Table 3.

Survival related to para-aortic lymph node status

| Study | (neo)adjuvant therapy (n/N) | Para-aortic LNM | Percentage of patients (N) | Survival rate |

Median survival (months) | P-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 y | 2 y | 3 y | 5 y | ||||||

| Doi et al. (2007)21 | 75 adjuvant 5FU, 66 radiation | Yes | 14% (19) | 16% | 0% | 5 | < 0.05 | ||

| No | 86% (114) | 13 | |||||||

| Nappo et al. (2015)31 | 14/135 neoadjuvant | Yes | 17% (15) | 32 | > 0.05 | ||||

| No | 83% (75) | 34 | |||||||

| Paiella et al. (2015)29 | 54/67 adjuvant | Yes | ?% (14) | 0% | 17 | NR | |||

| No | 20.3% | 30 | |||||||

| Sakai et al. (2005)25 | NR | Yes | 29% (34) | 30% | 7% | 3% | 8 | 0.1175 | |

| No | 71% (84) | 42% | 19% | 12% | 9 | ||||

| Schwarz et al. (2014)26 | 69/111 adjuvant 5FU/gemcitabine | Yes | 34% (32) | 15 | 0.110 | ||||

| No | 66% (62) | 21 | |||||||

| Shrikhande et al. (2007)27 | 23/29 (neo)adjuvant 5FU, gemcitabine or radiation | Yes | ?% (9) | 27 | N/A | ||||

| No | |||||||||

| Yamada et al. (2009)28 | 14/45 adjuvant 5FU/gemcitabine and 26/45 radiation | Yes | 19% (45) | 8 | 0.0029 | ||||

| NR | No | 81% (188) | 11 | ||||||

| Andersen et al. (1994)18 | NR | Yes | 24% (14) | 6 | 0.004 | ||||

| No | 76% (45) | 16 | |||||||

| Connor et al. (2004)19 | 5/8 adjuvant chemo (NOS) | Yes | 23% (10) | 0% | 15 | NR | |||

| 5/29 adjuvant chemo (NOS) | Noa | 77% (34) | 0% | 17 | |||||

NR, not reported; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; N/A, not applicable.

The assessed metastatic lymph node station was compared to N1/16b- and N0 patients together, instead of N1/16b- only.

P-value for difference in median survival.

Estimated pooled mean survival was 13 [95%CI 8–17] months in 169 patients with para-aortic LNM compared to 17 [6–27] months in 506 patients with N1-disease without para-aortic LNM. Estimated pooled mean difference could be generated from 5 studies and was 5 [95%CI 2–7, P < 0.001] months. There was moderate statistical heterogeneity among these 5 pooled studies (I2 = 53%, p = 0.080).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding all non-PDAC cancers (Table 1). Three studies included patients with both pancreatic and periampullary cancer.18, 19, 31 One study did not report separate survival times and was excluded from the sensitivity analysis.18

For PDAC, estimated pooled mean survival was 13 [95%CI 5–21] months in 33 patients with hepatic-artery LNM compared to 15 [12–19] months in 119 patients with N1-disease without hepatic-artery LNM. Estimated pooled mean difference was 3 [95%CI 2–7, p = 0.250] months. For PDAC, estimated pooled mean survival was 11 [95%CI 5–16] months in 65 patients with para-aortic LNM compared to 20 [8–31] months in 246 patients with N1-disease without para-aortic LNM. Estimated pooled mean difference was 8 [95%CI 0–16, p = 0.040] months.

Discussion

In the first systematic review on this subject, reduced survival was found following intraoperative detection of hepatic-artery or para-aortic LNM in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer. Survival was reduced further in patients with para-aortic LNM, compared to patients with hepatic-artery LNM. Data on survival in patients in whom the surgical exploration was aborted after intraoperative detection of LNM are lacking.

No studies were specifically designed to investigate if positive hepatic-artery, or para-aortic LNM should automatically preclude a resection in all patients. None of the included studies reported survival after aborted explorations due to detection of intraoperative LNM. Patients with metastasized pancreatic cancer have an overall survival of about 7 months when treated with gemcitabine and up to 11 months when treated with FOLFIRINOX, which is reserved for fitter patients.5 Survival of patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer is around 10 months.3, 4, 32 The pooled data demonstrate that patients with (pancreatic) cancer and hepatic-artery LNM had an estimated pooled mean survival of 15 months. Estimated pooled mean survival following pancreatoduodenectomy with para-aortic LNM was 13 months. The interpretation of the aggregated data is challenging due to several factors. Most of the included studies performed lymph node sampling in a subset of patients only, although these indications were mostly not given. It could be based on a surgeon's preference, i.e. an intraoperative finding of macroscopically suspicious lymph nodes or patients with other risk factors for poor survival such as extensive disease. As such, lymph node sampling may have been selectively performed in patients with a poorer prognosis, leading to worse survival rates. Conversely, resection in case of LNM may have been performed in younger patients with fewer comorbidities, as it is felt these patients might still benefit from a resection. The influence of comorbid conditions on outcomes following surgery is well known.33, 34 Furthermore, few data were available on (neo)adjuvant treatment, for instance with FOLFIRINOX, in the included studies. All studies described only the total number of patients receiving adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment. They did not describe the number of patients with, or without LNM specifically receiving these treatments. It was therefore not possible to analyze the impact of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy on outcomes in patients with, or without LNM. It could be hypothesized that neoadjuvant treatment may reduce the amount of LNM but data are currently lacking. Finally, there was no detailed information concerning the histopathological examination of lymph nodes (H&E, PCR, sentinel node). A recent analysis among 67 patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for pancreatic head cancer, demonstrated by matched case–control analysis demonstrated that the disease-free survival of patients with resected para-aortic LNM (19 months) was in between patients with resected negative para-aortic nodes (27 months), and patients with locally advanced disease (14 months).29 This review confirms the need for large, prospective studies in which in all patients lymph nodes are sampled and baseline characteristics are well documented in order to create a clinical risk model for survival after intra-operatively detected LNM.

Sensitivity analysis was performed for PDAC separately, as outcomes may differ from periampullary (distal CBD, papilla, duodenum) cancers, and clear differences exist in survival between the various periampullary cancers and PDAC.35, 36 Therefore, some of the largest studies in this review describing only ‘cancer of the pancreatic head’ which may involve distal cholangiocarcinoma were excluded from sensitivity analysis. Survival in patients with PDAC and LNM was shorter compared to patients with other periampullary cancers and LNM: survival in patients with PDAC and hepatic-artery or para-aortic LNM was 13 and 11 months, respectively, compared to 15 and 13 months for all patients. Estimated pooled mean difference in survival was not significant for PDAC patients with, or without hepatic-artery LNM undergoing resection. However, interpretation of the data remains difficult due to the issues raised above, and low patient numbers.

According to the TNM classification, para-aortic lymph nodes are extra-regional nodes for both pancreatic and periampullary cancer. According to the TNM, the hepatic-artery lymph node is either regional (pancreatic and bile duct cancer) or extra regional (ampullary cancer).37 Recently, the ISGPS introduced a consensus definition of a standard lymphadenectomy in patients with pancreatic cancer which included the hepatic-artery lymph node, but not the para-aortic lymph nodes.11 The ISGPS consensus was partly based on 4 randomized controlled trials (RCT's) investigating the value of an extended lymphadenectomy, which included various lymph node stations.38, 39, 40, 41

Prior studies have demonstrated that both preoperative CT-imaging and visual inspection cannot reliably determine LNM.12, 26 The accurate determination of (loco) regional LNM by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) even seems similar.42, 43, 44 Extra-regional lymph nodes may not be visible on EUS. This suggests that in case of clinical consequences such as aborting a surgical exploration, standard intraoperative sampling of hepatic-artery and para-aortic lymph nodes should be performed. Previous studies have demonstrated that the para-aortic lymph node station is important in pancreatic lymphatic drainage.45, 46 Indeed, occurrence of para-aortic LNM has been associated with LNM in more proximal nodes such as stations 13, 14 and other peripancreatic lymph nodes.26, 29, 47

The method to estimate mean survival times using reported medians, ranges and sample sizes has been widely used and validated.16 Although survival times may be skewed due to some patients surviving longer, the estimation is distribution-free. Furthermore, long-term survival following resection of pancreatic cancer is extremely rare, which restricts the skewness of survival data.48 Attempts have been made to improve the estimations, but they remain to be validated.49 Therefore the methods were used as described. Survival ranges needed to estimate mean survival times were deducted from Kaplan–Meier curves in 6 out of 7 studies of patients with para-aortic LNM. In these cases <10% of patients were alive at the end of follow-up. This has been taken into account when interpreting the pooled data. There was moderate statistical heterogeneity in the pooled studies regarding para-aortic LNM. However, the I-squared static has lower power when studies have small sample sizes. While the methodological quality of the included studies is adequate, studies were mostly small and retrospective. Large, prospective studies are needed to establish clinical risk models to determine if, and if so which patients might benefit of a resection. These studies should report outcomes of PDAC and peri-ampullary cancer separately. With the introduction of the ISGPS consensus on a standard lymphadenectomy, larger and prospective studies can now be performed and compared.

Conclusion

Hepatic-artery and especially para-aortic LNM detected during exploration for pancreatic or periampullary cancer is associated with reduced survival. Resection in patients with hepatic-artery LNM seems reasonable as survival times are better compared to patients with irresectable disease and this node is part of the ISGPS standard lymphadenectomy. In patients with para-aortic LNM proceeding with resection is less obvious, but due to a lack of adequate control groups and data on (neo)adjuvant therapy it remains unclear whether intra-operative detection of para-aortic LNM should automatically preclude resection in all patients.

Financial declarations/conflicts of interest

This research was in part funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant number UVA2013-5842)

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the help of F.S. van Etten-Jamaludin, clinical librarian, in designing and conducting the literature searches.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2016.05.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Coupland V.H., Kocher H.M., Berry D.P., Allum W., Linklater K.M., Konfortion J. Incidence and survival for hepatic, pancreatic and biliary cancers in England between 1998 and 2007. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:e207–e214. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karim-Kos H.E., de Vries E., Soerjomataram I., Lemmens V., Siesling S., Coebergh J.W. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: a combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1345–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louvet C., Labianca R., Hammel P., Lledo G., Zampino M.G., Andre T. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poplin E., Feng Y., Berlin J., Rothenberg M.L., Hochster H., Mitchell E. Phase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3778–3785. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy T., Desseigne F., Ychou M., Bouché O., Guimbaud R., Bécouarn Y. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron J.L., He J. Two thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S.C., Shyr Y.M., Wang S.E. Long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinomas. HPB. 2013;15:951–957. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song K.B., Kim S.C., Hwang D.W., Lee J.H., Lee D.J., Lee J.W. Matched case-control analysis comparing laparoscopic and open pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with periampullary tumors. Ann Surg. 2015;262:146–155. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn T.A., Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Koniaris L., Kaushal S., Abrams R.A. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2000;4:567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zacharias T., Jaeck D., Oussoultzoglou E., Neuville A., Bachellier P. Impact of lymph node involvement on long-term survival after R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:350–356. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tol J.A., Gouma D.J., Bassi C., Dervenis C., Montorsi M., Adham M. Definition of a standard lymphadenectomy in surgery for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a consensus statement by the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2014;156:591–600. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1726-6_59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng D.S., van Santvoort H.C., Fegrachi S., Besselink M.G., Zuithoff N.P., Borel Rinkes I.H. Diagnostic accuracy of CT in assessing extra-regional lymphadenopathy in pancreatic and peri-ampullary cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Oxford 2011 Levels of evidence 2 [Internet] Oxford Centre of Evidence Based Medicine; 2011. http://www.cebm.net/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/ Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells G.A., Shea B., O'Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M. 2000. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hozo S.P., Djulbegovic B., Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Cochrane Collaboration . The Nordic Cochrane Centre; Copenhagen: 2014. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen H.B., Baden H., Brahe N.E., Burcharth F. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:545–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connor S., Bosonnet L., Ghaneh P., Alexakis N., Hartley M., Campbell F. Survival of patients with periampullary carcinoma is predicted by lymph node 8a but not by lymph node 16b1 status. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1592–1599. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordera F., Arciero C.A., Li T., Watson J.C., Hoffman J.P. Significance of common hepatic artery lymph node metastases during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2330–2336. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doi R., Kami K., Ito D., Fujimoto K., Kawaguchi Y., Wada M. Prognostic implication of para-aortic lymph node metastasis in resectable pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:147–154. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaFemina J., Chou J.F., Gonen M., Rocha F.G., Correa-Gallego C., Kingham T.P. Hepatic arterial nodal metastases in pancreatic cancer: is this the node of importance? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1092–1097. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massucco P., Ribero D., Sgotto E., Mellano A., Muratore A., Capussotti L. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastases in pancreatic head cancer treated with extended lymphadenectomy: not just a matter of numbers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3323–3332. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philips P., Dunki-Jacobs E., Agle S.C., Scoggins C., McMasters K.M., Martin R.C. The role of hepatic artery lymph node in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: prognostic factor or a selection criterion for surgery. HPB. 2014;16:1051–1055. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai M., Nakao A., Kaneko T., Takeda S., Inoue S., Kodera Y. Para-aortic lymph node metastasis in carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Surgery. 2005;137:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz L., Lupinacci R.M., Svrcek M., Lesurtel M., Bubenheim M., Vuarnesson H. Para-aortic lymph node sampling in pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2014;101:530–538. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrikhande S.V., Kleeff J., Reiser C., Weitz J., Hinz U., Esposito I. Pancreatic resection for M1 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:118–127. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada S., Nakao A., Fujii T., Sugimoto H., Kanazumi N., Nomoto S. Pancreatic cancer with paraaortic lymph node metastasis: a contraindication for radical surgery? Pancreas. 2009;38:e13–e17. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181889e2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paiella S., Malleo G., Maggino L., Bassi C., Salvia R., Butturini G. Pancreatectomy with para-aortic lymph node dissection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: pattern of nodal metastasis spread and analysis of prognostic factors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1610–1620. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2882-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malleo G., Maggino L., Capelli P., Gulino F., Segattini S., Scarpa A. Reappraisal of nodal staging and study of lymph node station involvement in pancreaticoduodenectomy with the Standard International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery Definition of Lymphadenectomy for Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.019. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nappo G., Borzomati D., Perrone G., Valeri S., Amato M., Petitti T. Incidence and prognostic impact of para-aortic lymph nodes metastases during pancreaticoduodenectomy for peri-ampullary cancer. HPB. 2015;17:1001–1008. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha Lima C.M., Green M.R., Rotche R., Miller W.H., Jr., Jeffrey G.M., Cisar L.A. Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3776–3783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyder O., Dodson R.M., Nathan H., Schneider E.B., Weiss M.J., Cameron J.L. Influence of patient, physician, and hospital factors on 30-day readmission following pancreatoduodenectomy in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dias-Santos D., Ferrone C.R., Zheng H., Lillemoe K.D. Fernandez-Del Castillo C. The Charlson age comorbidity index predicts early mortality after surgery for pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2015;157:881–887. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tol J.A., Brosens L.A., van Dieren S., van Gulik T.M., Busch O.R., Besselink M.G. Impact of lymph node ratio on survival in patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Br J Surg. 2015;102:237–245. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bettschart V., Rahman M.Q., Engelken F.J., Madhavan K.K., Parks R.W., Garden O.J. Presentation, treatment and outcome in patients with ampullary tumours. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1600–1607. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Union Against Cancer (UICC) In: TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th ed. Sobin LH G.M., Wittekind C., editors. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedrazzoli S., DiCarlo V., Dionigi R., Mosca F., Pederzoli P., Pasquali C. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimura Y., Nagino M., Takao S., Takada T., Miyazaki K., Kawarada Y. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy in radical pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: long-term results of a Japanese multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:230–241. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0466-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeo C.J., Cameron J.L., Lillemoe K.D., Sohn T.A., Campbell K.A., Sauter P.K. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg. 2002;236:355–366. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200209000-00012. discussion 66–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farnell M.B., Pearson R.K., Sarr M.G., DiMagno E.P., Burgart L.J., Dahl T.R. A prospective randomized trial comparing standard pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatoduodenectomy with extended lymphadenectomy in resectable pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 2005;138:618–628. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.06.044. discussion 28–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mansfield S.D., Scott J., Oppong K., Richardson D.L., Sen G., Jaques B.C. Comparison of multislice computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography with operative and histological findings in suspected pancreatic and periampullary malignancy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1512–1520. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cannon M.E., Carpenter S.L., Elta G.H., Nostrant T.T., Kochman M.L., Ginsberg G.G. EUS compared with CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography and the influence of biliary stenting on staging accuracy of ampullary neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeWitt J., Devereaux B., Chriswell M., McGreevy K., Howard T., Imperiale T.F. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and multidetector computed tomography for detecting and staging pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:753–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirono S., Tani M., Kawai M., Okada K., Miyazawa M., Shimizu A. Identification of the lymphatic drainage pathways from the pancreatic head guided by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging during pancreaticoduodenectomy. Dig Surg. 2012;29:132–139. doi: 10.1159/000337306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirai I., Murakami G., Kimura W., Nara T., Dodo Y. Long descending lymphatic pathway from the pancreaticoduodenal region to the para-aortic nodes: its laterality and topographical relationship with the celiac plexus. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 2001;77:189–199. doi: 10.2535/ofaj1936.77.6_189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagakawa T., Kobayashi H., Ueno K., Ohta T., Kayahara M., Miyazaki I. Clinical study of lymphatic flow to the paraaortic lymph nodes in carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Cancer. 1994;73:1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940215)73:4<1155::aid-cncr2820730406>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paniccia A., Hosokawa P., Henderson W., Schulick R.D., Edil B.H., McCarter M.D. Characteristics of 10-year survivors of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:701–710. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan X., Wang W., Liu J., Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.