Abstract

Chondral lesions are difficult-to-treat entities that often affect young and active people. Moreover, cartilage has limited intrinsic healing potential. The purpose of this systematic literature review was to analyse whether the single-step scaffold-based cartilage repair in combination with microfracturing (MFx) is more effective and safe in comparison to MFx alone.

From the three identified studies, it seems that the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair in combination with MFx leads to similar short- to medium-term (up to five years follow-up) results, compared to MFx alone. All of the studies have shown improvements regarding joint functionality, pain and partly quality of life.

Keywords: Cartilage defects, Microfracturing, Autologous chondrocyte implantation, Chondrogenesis, Matrix-assisted cartilage repair

1. Introduction

A chondral or osteochondral lesion is a debilitating condition. Besides the older people (with degenerative cartilage damage), the young and active persons, especially, are likely to acquire chondral or osteochondral lesions, mainly caused by traumatic events (e.g. sport injuries). Due to the low intrinsic healing capacity of human articular cartilage, spontaneous healing of the damaged tissue cannot be expected. In addition to pain and functional impairment, resulting in a reduced quality of life, cartilage lesions can lead to the development of osteoarthritis and a further progression can lead to the requirement of a joint replacement.1, 2

There are numerous treatment options for chondral lesions, starting with conservative treatment and followed by surgical interventions. Generally, the treatment of chondral or osteochondral lesions aims at pain reduction, regaining joint mobility, reactivation of the affected area, preventing/slowing of the progression and prevention of osteoarthritis, and eventually avoiding total joint replacement.2, 3, 4

For small cartilage lesions, microfracturing (MFx) alone is considered as the first-line treatment for focal cartilage defects. MFx is a repair surgical technique that works by means of creating tiny fractures (e.g. by drilling) in the subchondral bone. The underlying idea is to promote cartilage regeneration from a so-called “super-clot” (after bleeding from the bone marrow). However, the procedure seems less effective in treating older patients, overweight patients, or cartilage lesions larger than 2.5 cm2.1, 2, 5, 6

For larger defects, the autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is indicated, which may also be used in combination with a matrix (MACI).2, 7 ACI is performed in different steps. In the first step, intact cartilage is sampled arthroscopically, preferably from a non-weight-bearing area of the affected cartilage. The generated cells are then cultured in vitro until there are enough cells to be re-implanted into the cartilage lesion. These autologous cells should adapt themselves to their new environment by forming new tissue. If chondrocytes are applied onto the damaged area in combination with a membrane (tibial periosteum or biomembrane) or pre-seeded in a scaffold matrix, this technique is called MACI. However, for (M)ACI, two surgeries are needed, resulting in higher costs.5, 8, 9

To overcome the disadvantages of MFx and (M)ACI, a new treatment option has evolved: the single-step scaffold-based treatment of cartilage defects. During this approach, a matrix is implanted in the area of the damaged cartilage to cover the blood clot after a bone marrow stimulation technique (e.g. MFx). This technique is also called autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC). The scaffolds are implanted arthroscopically or by a mini-arthrotomy for “in situ” repair, permitting the ingrowing of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to differentiate into the chondrogenic lineage. The used matrix acts as a temporary structure to allow the cells to be seeded. The fixation of the matrices can be done by e.g. suturing or glueing. This cartilage repair technique is done within one single surgery and can be used for larger defect sizes than 2.5 cm2.7, 10

The single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair is mainly an enhancement of the standard MFx technique, used to induce reparative marrow stimulation.11, 12 Thus, we exclusively focus on one approach, where the implantation of the scaffold is combined with MFx.

A total of eight products from eight manufacturers that can be used for the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair and are commercially available were identified. An overview of these products is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Product overview.

| Product | Manufacturer | Main component(s) |

|---|---|---|

| BST-CarGel® | Primal Enterprises Limited, Canada | Chitosan solution |

| CaReS®-1S | Arthro Kinetics AG, Germany | Collagen type I |

| Chondro-Gide® | Geistlich Pharma, Switzerland | Porcine collagen type I/III |

| Chondrotissue® | BioTissue Technologies GmbH, Switzerland | Polyglycolic acid fleece and freeze-dried sodium hyaluronate |

| GelrinC | Regentis Biomaterials Ltd., Israel | Hydrogel of polyethylene glycol di-acrylate (PEG-DA) and denatured fibrinogen |

| Hyalofast® | Anika Therapeutics, Inc., USA | Biodegradable hyaluronan (HYAFF®) |

| Maioregen™ | Fin-Ceramica Faenza S.p.A., Italy | Deantigenated type I equine collagen |

| MeRG® | Bioteck S.p.A., Italy | Microfibrillar collagen membrane |

References: individual manufacturers’ websites.

The aim of this report was to assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of the single-step matrix-assisted cartilage repair in the knee joint (combined with MFx), compared to MFx alone or (M)ACI.

2. Methods

2.1. Research questions

This systematic review should answer the following two questions:

-

(1)

Is the single-step scaffold-based cartilage repair in combination with MFx more effective and safe in comparison to MFx alone in patients with indications for cartilage knee surgery concerning the outcomes listed in Table 2?

-

(2)

Is the single-step scaffold-based cartilage repair in combination with MFx as effective, but safer, in comparison to two-step cartilage repair procedures (autologous chondrocyte implantation or matrix-induced, autologous chondrocyte implantation) in patients with indications for cartilage knee surgery concerning the outcomes listed in Table 2?

Table 2.

Inclusion criteria.

| Population | • Adult patients with indications for surgical cartilage repair in the knee • Grade III–IV (Outerbridge classification) localised cartilage damages/defects/disorders in the knee • Grade III–IV (ICRS classification) (osteo)chondral lesions • Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) • ICD-10 codes: M24.1, M94.8, M94.9, M93.2 |

| Intervention | • Single-step, cell-free, scaffold-based cartilage repair in combination with microfracturing |

| Control | • Microfracture surgery/microfracturing alone (main comparator) • Autologous chondrocyte implantation/transplantation (ACI/ACT) • Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI) |

| Outcomes | |

| Efficacy | • Mobility/joint functionality • Pain • Return to daily activities/sports/physical activity • Quality of life • Necessity of total joint replacement |

| Safety | • Adverse events • Mortality (up to 10 days postoperatively) • Re-operation/additional surgery |

| Study design | |

| Efficacy | • Randomised controlled trials • Prospective non-randomised controlled trials |

| Safety | • Randomised controlled trials • Prospective non-randomised controlled trials • Prospective uncontrolled trials (n > 50 pts., follow-up > 24 months) |

2.2. Search strategy

To answer the research questions, a systematic literature search was conducted between 13th and 15th of January 2016 in the following databases: The Cochrane Library, CRD (DARE, NHS-EED, HTA), Embase, Medline via Ovid and PubMed. Additionally, a search was conducted by hand and using Scopus, and manufacturers of the most common products were contacted (see Table 1). The literature search was limited to articles published in English or German.

2.3. Selection of studies

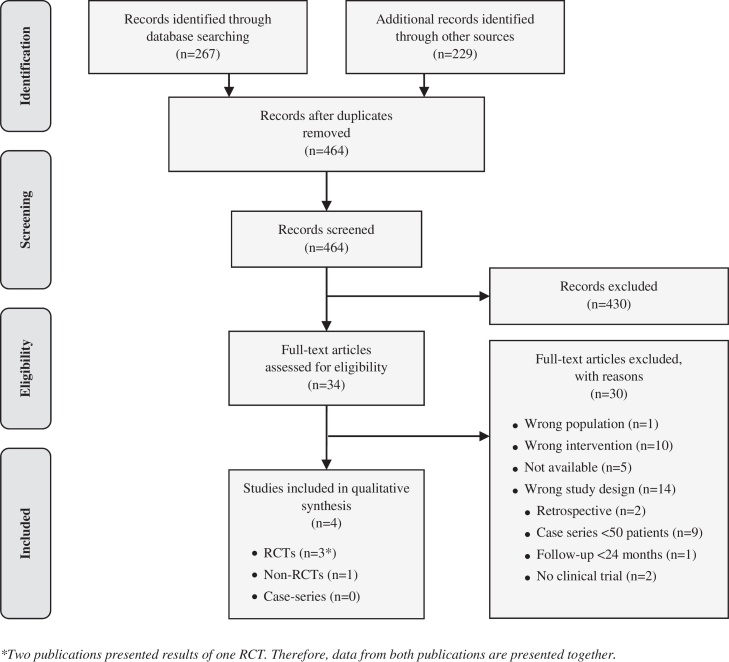

Two reviewers independently screened and selected the literature based on the criteria listed in Table 2. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Flow Diagram depicting the flow of records from identification to inclusion is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection (PRISMA flow diagram). *Two publications presented results of one RCT. Therefore, data from both publications are presented together.

First of all, we focused on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs). Case series were exclusively considered for assessing safety-related outcomes. However, we excluded case series with less than 50 patients or a follow-up of less than 2 years. These cut-off points were chosen to focus on case series that might identify also rare complications and complications occurring a long time after surgery.

Moreover, we excluded all studies in which the single-step matrix-assisted cartilage repair was not exclusively performed in combination with MFx. Due to this reason, we excluded one non-randomised controlled trial (patients in the control group received MACI) and two single-arm studies, in which the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair was used in combination with different techniques of subchondral drilling and with no additional intervention.

Furthermore, we excluded retrospective studies – even controlled studies with a retrospective control group – because the sources of error due to confounding and bias are more common in retrospective studies than in prospective ones.

2.4. Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted data from the selected studies. In case of discordances, consensus was reached by discussion. Extracted data included study characteristics such as study design or mean age of patients (see Table 3) and efficacy plus safety outcomes (see Table 4, Table 5).

Table 3.

Study characteristics.

| Reference | Intervention | Control | Study design | Number of patients |

Mean age of patients (in yrs.) |

Sex of patients (M/F) |

Mean defect size (cm2) |

Followup (months) | Loss to follow-up (% of pts.) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | |||||

| Anders et al. 2013d | Arthroscopy + mini-arthrotomy, single-step cartilage repaira + MFx | Arthroscopic MFx alone | RCT | 13|15 | 10 | 33|38 | 41 | 85|80/15|20 | 80/20 | 3.7|3.5 | 2.9 | 24 | 38|13 | 40 |

| Sharma et al. 2013e | Mini-arthrotomy, single-step cartilage repair + MFx | Miniarthrotomic MFx alone | Non-RCTb | 15 | 3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Shive et al. 2014f (Stanish et al. 2013g)c | Arthroscopy + mini-arthrotomy, single-step cartilage repair + MFx | Arthroscopic MFx alone | RCT | 41 | 39 | 35 | 37 | 56/44 | 64/36 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 60 | 20 | 33 |

Abbreviations: I, intervention; C, control; RCT, randomised controlled trial; non-RCT, non-randomised controlled trial; vs., versus; N/A, no data; yrs., years; M/F, male/female; MFx, microfracturing.

Study with two intervention groups: in one group, scaffold was sutured; in the other group, scaffold was glued into the affected area.

Study was initially conducted as RCT. However, randomisation was stopped after only three patients were assigned to the control group. Study was then treated as non-RCT.

Study results after 1 year were published in Stanish 2013 (assessing 41 vs. 37 pts.) and results after 5 years follow-up were presented in Shive 2014 (assessing 34 vs. 26 pts.). Therefore, data from both publications are presented together.

Ref. 15.

Ref. 18.

Ref. 16.

Ref. 17.

Table 4.

Study outcomes: clinical effectiveness.

| Reference | Follow-up | Mobility/joint functionality (mean change from baseline) |

Quality of life (mean change from baseline) |

Pain (mean change from baseline) |

Necessity of total joint replacement |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | I | C | ||

| Modified ICRS score | Modified Cincinnati score (6–100) | VAS (0–100) | n (%) of patients | ||||||||||||

| Anders et al. 2013a,c | Baseline | N/A | 47 (±20)|47 (±15) | 37 (±14) | 46(±N/A)|48 (±N/A) | 54 (±N/A) | N/A | ||||||||

| p = N/A | p = N/A | ||||||||||||||

| 12 mo | N/A | +35 (±29)|+19 (±22) | +31 (±13) | −32 (±N/A)|−32 (±N/A) | −35(±N/A) | N/A | |||||||||

| p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | |||||||||||||

| 24 mo | N/A | +46 (±17)|+37 (±14) | +44 (±15) | −37 (±N/A)|−38 (±N/A) | −49 (±N/A) | 0|1 (8) | 0 | ||||||||

| p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | p = N/A | ||||||||||||

| IKDC score (0–100) | Frequency | Severity | |||||||||||||

| Sharma et al. 2013d | Baseline | N/A | 77 (±20.3) | 84.3 (±24.5) | 54.3 (±16.4) | 54 (±21) | |||||||||

| p = NS | p = N/A | p = N/A | |||||||||||||

| 3 mo | N/A | −41 (±N/A) | −62.6 (±N/A) | −29 (±N/A) | −34.7 (±N/A) | ||||||||||

| p = NS | p = N/A | p = N/A | |||||||||||||

| 6 mo | N/A | −52.9 (±N/A) | −41 (±N/A) | −32.1 (±N/A) | −15.3 (±N/A) | ||||||||||

| p = NS | p = N/A | p = N/A | |||||||||||||

| WOMAC subscale score stiffness (0–20) | WOMAC subscale score function (0–170) | SF-36 v2 physical component | SF-36 v2 mental component | WOMAC subscale score pain (0–50) | |||||||||||

| Shive et al. 2014e (Stanish et al. 2013f)b | Baseline | 10.5 (±4.4) | 9.4 (±4.9) | 80.3 (±38.5) | 75.9 (±38) | N/A | N/A | 22.4 (±10.3) | 22.9 (±9.1) | ||||||

| p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | |||||||||||||

| 12 mo | −6.0 (±0.7) | −6.6 (±0.7) | −56.0 (±4.2) | −60.6 (±4.4) | +13.0 (±1.5) | +14.8 (±1.5) | +3.5 (±1.6) | +0.8 (±1.6) | −16.16 (±1.16) | −16.91 (±1.21) | |||||

| p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | |||||||||||

| 60 mo | −5.6 (±0.7) | −6.7 (±0.6) | −56.5 (±4.6) | −62.1 (±3.4) | +13.1 (±1.6) | +14.4 (±1.4) | +2.7 (±1.3) | +0.2 (±1.8) | −15.37 (±1.47) | −16.56 (±1.19) | |||||

| p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | p = NS | |||||||||||

Abbreviations: I, intervention; C, control; CHG, change (after); ICRS, International Cartilage Repair Society; IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; mo, months; n, number; N/A, no data; SF-36 v2, Short-Form Health Survey version 2; yrs., years; VAS, visual analogue scale; ±, standard deviation; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Study with two intervention groups: in one group, scaffold was sutured; in the other group, scaffold was glued into the affected area.

Study results after 1 year were published in Stanish 2013 (assessing 41 vs. 37 pts.) and results after 5 years follow-up were presented in Shive 2014 (assessing 34 vs. 26 pts.). Therefore, data from both publications are presented together.

Ref. 15.

Ref. 18.

Ref. 16.

Ref. 17.

Table 5.

Study outcomes: safety.

| Reference | Follow-up | Complications |

Re-operation rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I |

C |

I |

C |

I |

C |

||

| Procedure-related in n (%) of patients | Device-related in n (%) of patients | n (%) of patients | |||||

| Anders et al. 2013a,c | 24 mo | 0|0 | 0 | 0|0 | – | N/A | |

| Sharma et al. 2013d | 6 mo | 1 (7) | 0 | N/A | – | N/A | |

| Shive et al. 2014e (Stanish et al. 2013f)b | 12 mo | 38 (93) | 30 (77) | 9 (22) | – | N/A | |

| p = N/A | |||||||

| 60 mo | 2 (6) | 2 (8) | 1 (3) | – | |||

| p = N/A | |||||||

Abbreviations: I, intervention; C, control; mo, months; n, number; N/A, no data.

Study with two intervention groups: in one group, scaffold was sutured; in the other group, scaffold was glued into the affected area.

Study results after 1 year were published in Stanish 2013 (assessing 41 vs. 37 pts.) and results after 5 years follow-up were presented in Shive 2014 (assessing 34 vs. 26 pts).

Ref. 15.

Ref. 18.

Ref. 16.

Ref. 17.

2.5. Methodological quality and validity assessment

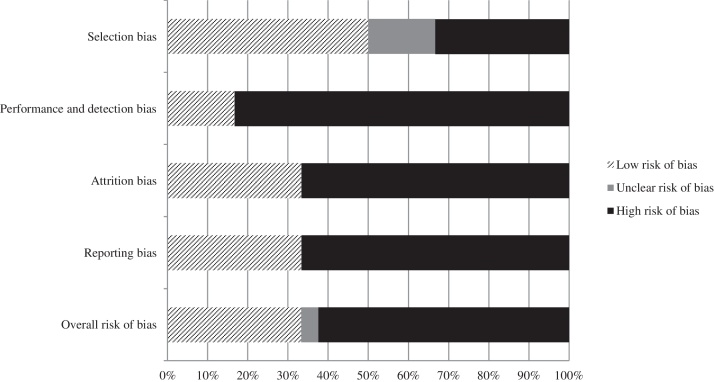

The risk of bias (internal validity) of the studies was judged by two independent researchers based on the guidelines of EUnetHTA (European Network for Health Technology Assessment).13, 14 In case of discordances, consensus was reached by discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

After deduplication, the literature search resulted in overall 464 hits for consideration. Screening of title and abstract led to identification of 34 potentially relevant references, for which we retrieved the full texts. Of the 34 full-text articles, 25 did not meet our inclusion criteria due to the following reasons: wrong population (1), wrong intervention (10) or wrong study design (14). For a total of five publications, no full-text articles were available. The selection process yielded four publications on three studies that met our inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1). Two were randomised controlled trials1 (RCTs)15, 16, 17 and one was a non-randomised controlled trial (non-RCT)18; with a total of 136 patients (84 in the scaffold and 52 in the control groups). All three studies assessed the clinical effectiveness and safety of the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair in the knee joint in combination with MFx in comparison to MFx alone.

The mean age of patients ranged from 33 to 38 years in the treatment groups and from 37 to 41 years in the control groups across trials. Across trials, between 15 and 44% of the patients in the scaffold groups and 20–36% of the patients in the control groups were of the female sex. Patients had grade 3–4 (Outerbridge classification) of chondral defects with a mean lesion size of 2.3–3.7 cm2 in the scaffold groups and 2–2.9 cm2 in the control groups.15, 16, 17, 18

3.2. Clinical effectiveness

For assessing the clinical effectiveness, the following four outcomes were defined as crucial: mobility/joint functionality, quality of life, pain and necessity of a total joint replacement. These patient-relevant outcomes were chosen to represent the aims of cartilage repair.

Below, only selected outcomes, measured at the latest follow-up time point, are summarised. Detailed outcome data are provided in Table 4, Table 5.

3.2.1. Mobility or joint functionality

The effect on mobility or joint functionality was measured in all three controlled trials by five different scoring systems.15, 16, 17, 18

In one RCT with 38 patients and in two scaffold groups (one group received a glued, the other group a sutured scaffold), the joint functionality was measured with the Modified Cincinnati score (scale: 6–100) and with (a modified) ICRS score (International Cartilage Repair Society). The Modified Cincinnati Score increased in all study groups over time. After 24 months, the score improved by 46 and 37 points in both treatment groups and by 44 points in the control group (compared to baseline). The improvement of the score was not significantly different between the study groups. However, in all study groups, the improvement of the score from baseline was statistically significant.15

In the second RCT, joint functionality was measured with the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) subscale scores for stiffness (scale: 0–20) and for function (scale: 0–170). After 60 months, the score for stiffness improved by 5.6 points in the treatment group and by 6.7 points in the control group (compared to baseline). The score for function improved in both study groups over time. After 60 months, this score improved by approximately 57 points in the scaffold group and by approximately 62 points in the MFx group. The differences of the changes of the WOMAC sub-scores between the study groups were statistically not significant. However, both study groups showed significant improvement from baseline in both subscales.16, 17

In the non-RCT, joint functionality was measured with the IKDC Score (International Knee Documentation Committee, scale: 0–100). However, it was only stated that the score improved over time in both study groups, whereas the differences of the score changes between the study groups were statistically not significant after 3 and 6 months of follow-up.18

Overall, all three studies have shown improvements in joint functionality in both study groups. However, the improvement in the scaffold groups was not significantly better, compared to the control groups.15, 16, 17, 18

3.2.2. Necessity of a total joint replacement

The necessity of a total joint replacement was reported in one RCT.15 In one patient who received a (glued) scaffold, the knee joint had to be replaced. In none of the patients who underwent MFx alone, the joint had to be replaced (likewise for patients who received a sutured scaffold).15 It was not stated whether the difference between the study groups was significant or not.

3.2.3. Quality of life

The quality of life was measured in one RCT using the mental and physical components of the SF-36 (version 2). After 60 months (compared to baseline), the scores improved by 13.1 points and 2.7 points in the treatment group, and in the control group the scores improved by 14.5 points for the mental component and decreased by nearly 0.2 points for the physical component. It was exclusively stated that the difference in changes of the score between the study groups was statistically not significant.16, 17

3.2.4. Pain

In one RCT, pain was measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS; scale: 0–100). The score for pain significantly improved over time in both treatment groups, compared to baseline. After 24 months (compared to baseline), the score improved by 37 points in the treatment group and by 38 points in the control group. However, the difference in changes of the scores between the study groups was statistically not significant.15

In the other identified RCT, pain was measured with the WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) subscale score for pain (scale: 0–50). After 60 months (compared to baseline), the score improved by 15.4 points in the treatment group and by 16.6 points in the control group, whereas the improvement was statistically significant in both study groups. However, the difference in changes of the scores between the study groups was statistically not significant.16, 17

In the identified non-RCT, the severity and frequency of pain were measured. However, it was not stated on which scale or scoring system the measurement was based on. After six months, the score for the severity of pain improved by 32.1 points in the treatment group and by 15.3 points in the control group. The score for the frequency of pain improved after 6 months of follow-up by 52.9 points in the treatment group and by 41 points in the control group. The scores for frequency and severity of pain significantly improved in the intervention group. For the control group, there was no significant decrease of the pain scores. However, it was not stated whether the differences between the study groups in changes were statistically significant or not.18

Overall, the scores for pain improved significantly in all studies in the treatment groups and in two studies in the control groups, compared to baseline. Nevertheless, in none of the studies the improvement in the scaffold groups was significantly better than in the control groups.15, 16, 17, 18

3.3. Safety

For assessing the safety, the following outcomes were defined as crucial: procedure-related complications, device-related complications and re-operation rate. Procedure-related adverse events were defined as complications that are associated with the surgical intervention (e.g. events associated with anaesthesia, infections, damages to nerves or blood vessels, bleeding or the occurrence of blood clots). Device-related complications were defined as adverse events associated with the implantation of the scaffold (e.g. movement or release of the scaffold or allergic reactions).

3.3.1. Procedure-related complications

Adverse events – that were related to the surgical procedure, in comparison to MFx – were reported in all three identified trials. The reported rates ranged from 0 to 93% in the scaffold groups and from 0 to 77% in the MFx groups.15, 16, 17, 18

3.3.2. Device-related complications

Adverse events – that were related to the scaffold – occurred in 0–22% of the patients (reported in two RCTs).15, 16, 17 Since the control groups did not receive a scaffold, no scaffold-related complications occurred.

In none of the identified studies it was clearly stated which kind of adverse events occurred. In one study, it was stated that one patient in the treatment group had mild haemarthrosis.18 In another study, it was stated in general terms that the most frequent adverse events were arthralgia, pain and nausea in the treatment group, and arthralgia and pain in the control group.16, 17

3.3.3. Re-operation rate

In none of the identified studies it was stated if any re-operations were necessary or not.

3.4. Risk of bias

Due to the fact that relevant baseline characteristics (e.g. mean age and sex of patients) were not comprehensively provided or controlled for and the study protocol was switched from “randomised” to “non-randomised”, the risk of a selection bias was graded high for the non-RCT.18 Since in one RCT16, 17 no information on the allocation concealment was provided, the risk for a selection bias was partly unclear. Due to no blinding of the patients or study personnel in all identified studies,15, 16, 17, 18 the performance and detection bias was graded high. Furthermore, in the identified RCTs,15, 16, 17 there was a high rate of loss to follow-up (partly more than 30%); thus, the attrition bias was graded high for these two studies. For one RCT15 and for the non-RCT,18 no study protocol was available. Due to this reason, it was not possible to proof if all results of these two studies were published (or not published); thus, the risk of a reporting bias was graded high.

The overall risk of bias of the individual studies was graded high. An overview of the individual risks of bias is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias (study level).

4. Discussion

This systematic review has shown that the single-step matrix-assisted cartilage repair in the knee joint in combination with MFx can be an effective treatment option, particularly with regard to outcomes like joint functionality, quality of life and pain. However, when compared to MFx alone, the new treatment option did not show major benefits. Moreover, for the comparison with (matrix-assisted) autologous chondrocyte implantation, no evidence has been identified.

In total, we identified three clinical trials (two randomised trials15, 16, 17 and one non-randomised study18) involving 136 patients that met our inclusion criteria.

A major issue of the identified trials is the low number of patients of each study. Especially for identifying rare (unanticipated) complications, these patient numbers might be insufficient. Small numbers are furthermore likely to have impacted the trials’ ability to detect between-group differences in efficacy outcomes.

Two of the studies had a relatively short follow-up of one year or less.15, 18 Only one of the studies had a follow-up of at least five years.16 Therefore, reliable data of long-term efficacy and safety-related outcomes are missing.

The applied interventions differed slightly between the individual studies. First of all, in one study,16, 17 the scaffold was a hydrogel, and in the other studies, it was a kind of “fleece”.15, 18 Another potential effect on the outcomes could be the fixation technique of the scaffold (e.g. if it was glued or sutured). Furthermore, the MFx procedure in the control groups was either performed arthroscopically or by mini-arthrotomy.

Due to the incomprehensive or inconsistent reporting of adverse events across the majority of included studies, aggregated statements on the safety are barely possible. This was deemed an important shortcoming for the majority of included studies. In one RCT,16, 17 the rate of procedure-related complications rate was approximately 93% in the treatment group. In another RCT,15 the rates of procedure-related complications were only reported as 0%. This discrepancy hints at verifying definitions for safety. Furthermore, in none of the studies was it clearly stated and sufficiently explained which adverse events occurred.

Moreover, it was barely reported if patients received additional medication after the surgical procedure or even in the long run, e.g. for symptom control. It is evident that e.g. the intake of painkillers at the time of follow-up could have impacted the outcome assessment (e.g. for pain and quality of life).

One of the identified studies18 was initially conducted as RCT. However, the randomisation was stopped after only three patients were assigned to the control group. This study was treated as non-RCT in our report. Alternatively, it could have been considered as a case series since the change in protocol during the trial had the subsequent patients recruited exclusively to the scaffold arm to enlarge the safety database.

There is no robust evidence that the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage repair combined with MFx leads to better outcomes than MFx alone. From the extracted evidence, it appears that the intervention is not superior compared to MFx. Long-term data are lacking. Furthermore, there is a need for safety trials that focus on rare adverse events.

The main limitations of our systematic review are methodical, especially due to our exclusion criteria. First of all, we decided to exclude case series for assessing efficacy-related outcomes. Furthermore, we excluded case series with less than 50 patients and a follow-up of less than two years. Moreover, we excluded all studies in which the single-step matrix-assisted cartilage repair was not exclusively performed in combination with MFx. Therefore, it is possible that we excluded studies that reported results of e.g. other products or complications.

Moreover, it might be that we did not identify all appropriate studies, although we used different terms in the systematic literature search, asked the manufacturers for studies and supplemented our search by a handsearch and an additional search in Scopus. This is mainly due to the inconsistent wording for the assessed technology of cartilage repair. Thus, we identified a large part of the studies by handsearching. In addition, it is possible that we did not identify all manufacturers asking for studies.

5. Conclusion

From the studies, it appears that, the single-step scaffold-assisted cartilage in combination with MFx and the cartilage repair with MFx alone show positive treatment effects.

However, the current evidence is not sufficient to conclude that the single-step matrix-assisted cartilage repair (combined with MFx) is more effective and safer than MFx or as effective, but safer than (matrix-assisted) autologous chondrocyte implantation.

Nevertheless, the new technique seems to be very promising and should be re-evaluated when results from larger studies with longer follow-up are available.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Footnotes

Data from 2 publications of one study population, presenting results after 1 year and results after 5 years of follow-up, are presented together.

References

- 1.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons . 2010. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteochondritis Dissecans: Guidelines and Evidence Report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und orthopädische Chirurgie und Berufsverband der Ärzte für Orthopädie Leitlinien der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Orthopädie und Orthopädische Chirurgie und des Berufsverbandes der Ärzte für Orthopädie (BVO): Osteochondrosis dissecans des Kniegelenkes. Leitlinien der Orthopädie. 2002:2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erggelet C., Mandelbaum B., Lahm A. Der Knorpelschaden als therapeutische Aufgabe – Klinische Grundlagen. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin. 2000;51(2):48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logerstedt D.S., Snyder-Mackler Y., Ritter R.S., Axe M.J. Knee pain and mobility impairments: meniscal and articular cartilage lesions: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy. 2010;40(6):A1–A35. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.0304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makris E.A., Gomoll A.H., Malizos K.N., Hu J.C., Athanasiou K.A. Repair and tissue engineering techniques for articular cartilage. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(1):21–34. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinwachs M.R., Guggi T., Kreuz P.C. Marrow stimulation techniques. Injury. 2008;39(suppl 1):S26–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donaldson J., Tudor F., McDermott I.D. (IV) Treatment options for articular cartilage damage in the knee. Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(1):24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen N.J., Sullivan M., Ferkel R.D. Autologous chondrocyte implantation for treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Oper Tech Orthop. 2014;24(3):195–209. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thermann H., Becher C., Vannini F., Giannini S. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis and generational development of autologous chondrocyte implantation. Oper Tech Orthop. 2014;24(3):210–215. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benthien J.P., Behrens P. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC): combining microfracturing and a collagen I/III matrix for articular cartilage resurfacing. Cartilage. 2010;1(1):65–68. doi: 10.1177/1947603509360044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benthien J.P., Behrens P. The treatment of chondral and osteochondral defects of the knee with autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC): method description and recent developments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(8):1316–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kon E., Filardo G., Roffi A., Andriolo L., Marcacci M. New trends for knee cartilage regeneration: from cell-free scaffolds to mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5(3):236–243. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9135-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EUnetHTA Joint Action 2 . 2015. Internal Validity of Non-randomised Studies (NRS) on Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 14.EUnetHTA Joint Action 2 WP . 2013. Levels of Evidence: Internal Validity (of Randomized Controlled Trials) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anders S., Volz M., Frick H., Gellissen J. A randomized, controlled trial comparing autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) to microfracture: analysis of 1- and 2-year follow-up data of 2 centers. Open Orthop J. 2013;7:133–143. doi: 10.2174/1874325001307010133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shive M.S., Stanish W.D., McCormack R. BST-CarGel® treatment maintains cartilage repair superiority over microfracture at 5 years in a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Cartilage. 2014;6(2):62–72. doi: 10.1177/1947603514562064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanish W.D., McCormack R., Forriol F. Novel scaffold-based BST-CarGel treatment results in superior cartilage repair compared with microfracture in a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg. 2013;(95):1640–1650. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma B., Fermanian S., Gibson M. Human cartilage repair with a photoreactive adhesive–hydrogel composite. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(167):1–9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]