Abstract

This report discusses a case of nonconvulsive status epilepticus, caused by cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation. Brain biopsy demonstrated cerebral amyloid angiopathy, with clinical and radiographic features indicative of a fluctuating inflammatory process. Immunomodulatory treatment with pulse steroids resulted in rapid and dramatic clinical and radiographic improvement. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation should be considered in the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizures after the age of 40, when associated with fluctuating multifocal T2 hyperintensities and petechial hemorrhages on gradient echo (GRE) or susceptibility-weighted (SWI) MRI sequences.

Keywords: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, Inflammation, Status epilepticus, MRI, EEG, Pathology

1. Case report

We present a case of status epilepticus due to cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation, successfully treated with immunomodulation. A 52-year-old man with a history of hypertension and alcohol abuse, presented in January of 2015 with new-onset seizures. The patient's family first noted new-onset irritability, paranoia, and confusion that were thought to be atypical for him. Two days later, the patient noted a 45-minute episode of elementary visual hallucinations consisting of bright colors and stars in his right visual field with an associated expressive aphasia. He reported that he could understand questions and formulate responses in his head but not actually speak.

He was brought to an outside hospital where he had a witnessed seizure during which he had deviation of his head to the left, evolving to a generalized tonic-convulsion seizure lasting 40 seconds, with associated tongue biting and postictal confusion but no incontinence. His exam was notable only for a right inferior quadrant visual field defect, which was homonymous but more profound in the right eye. A lumbar puncture was performed, and cerebrospinal fluid was acellular with normal protein and glucose, with no oligoclonal bands, and with negative cytology and flow cytometry. Routine electroencephalograms (EEGs) showed spike–wave discharges with several electrographic seizures in the left occipital region. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed left occipital white matter and cortical T2 hyperintensity with mild focal mass effect, without enhancement but with petechial hemorrhages on gradient echo (GRE) imaging and with a second smaller focus of T2 hyperintensity in the left anterior insula (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance angiography of the head and neck was unremarkable. He was loaded with levetiracetam and was discharged from the hospital.

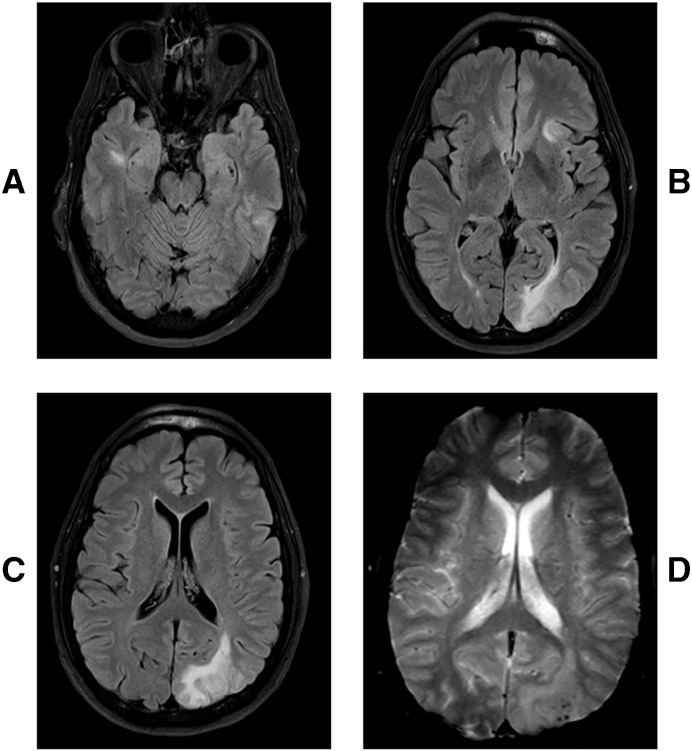

Fig. 1.

Axial T2 MRI FLAIR sequences with multifocal hyperintensities in the right temporal lobe (A), left anterior insula (B), and left occipital lobe (B, C). Blooming artifact over the left occipital region showing micro hemorrhages on the gradient echo sequences (D).

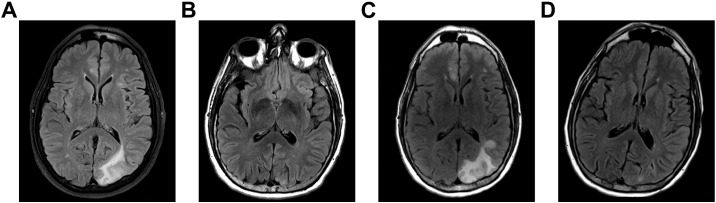

Upon initial formulation, the patient's history, exam, and studies were thought to be most consistent with a multifocal glioma, less likely an infectious or inflammatory process, and even less likely an old stroke. His levetiracetam dose was increased because of a recurrent episode of visual symptoms and aphasia, and he was scheduled for a biopsy of the left occipital lesion. However, a repeat MRI performed in March 2015 in preparation for the biopsy showed significant improvement of the left occipital and left anterior insular lesions (Fig. 2B). These shifting lesions were thought to be more consistent with a demyelinating process such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

Fig. 2.

Relapsing appearance of the left posterior quadrant lesion at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 9 months of symptom onset (A, B, C, D, respectively).

The brain biopsy was aborted, and the patient was instead admitted for an expedited inflammatory workup. A repeat lumbar puncture was again unrevealing (including negative oligoclonal bands, cytology, flow cytometry, and IgH gene rearrangement). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed multiple 1- to 2-cm hepatic lesions with peripheral nodular enhancements, which were then confirmed as hepatic hemangiomas on abdominal MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical and thoracic spine showed only mild degenerative disc disease, and CT angiogram of the head and neck was unremarkable.

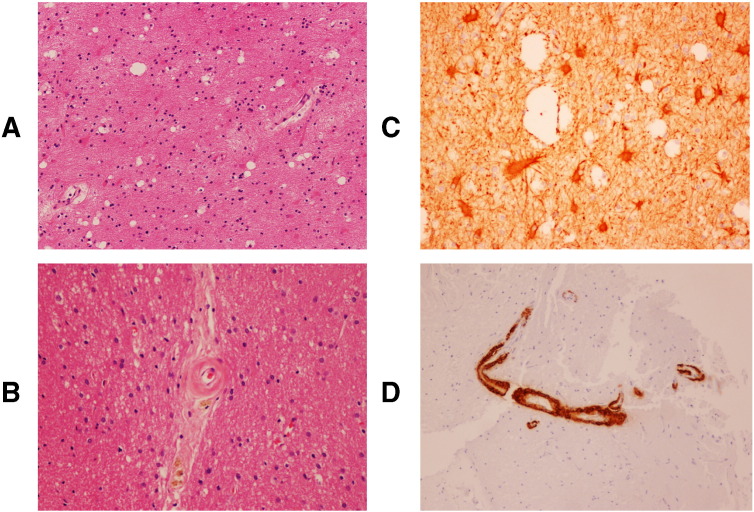

The patient was again discharged home, but follow-up MRI in June 2015 showed worsening of the left occipital T2 hyperintensity (Fig. 2C) and new left frontal T2 hyperintensities, as well as new enhancement of the lesion in the right anterior temporal lobe (not shown). Biopsy of the left occipital lesion was performed. The biopsy showed reactive changes and thickened blood vessels with beta-amyloid deposition in vessel walls (Fig. 3). These findings were thought to be consistent with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed reactive changes including vacuolization suggestive of edema and astrocytosis/gliosis (A). Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) staining highlighted reactive astrocytes (B). H&E staining also demonstrated thickened blood vessels with perivascular hemosiderin deposition (C), and beta-amyloid immunohistochemistry revealed beta-amyloid deposition in blood vessel walls (D). These findings were consistent with cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

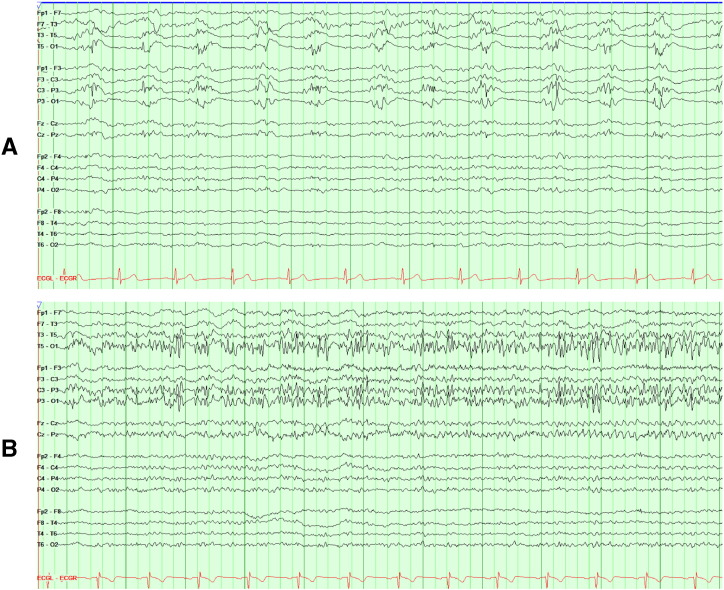

He was then brought to the emergency department for a sudden clinical deterioration with global aphasia and confusion. He was unable to name objects, repeat phrases, or follow commands; made frequent paraphasic errors; and was noted to have decreased blink to threat on the right. An EEG was obtained, revealing continuous lateralized periodic discharges with overlying fast activity over the left posterior quadrant (Fig. 4A), evolving into 3–4 electrographic seizures per hour (Fig. 4B), consisting of 9-Hz rhythmic sharp waves, without clinical return to baseline between seizures. He was therefore determined to be in nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) and was admitted. Over the course of approximately 24 h, he was started on lacosamide, phenytoin, and valproic acid in addition to levetiracetam, and NCSE was aborted. Notably, Mr. G's clinical status improved only slightly with the arrest of seizures, and he continued to demonstrate significant global aphasia and confusion.

Fig. 4.

Continuous lateralized periodic discharges with overlying fast activity (LPD + F) over the left posterior quadrant (maximal at O1 > P3/T5) (A), evolving into 3–4 electrographic seizures per hour, consisting of 9-Hz rhythmic sharp activity (B), without clinical return to baseline between seizures.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan of the brain and whole body revealed increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the left occipital and left temporal regions, consistent with the known lesions on MRI. These areas of increased FDG uptake were thought to be most likely due to an inflammatory process and less likely due to recent seizure activity. At this point, the diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation was advanced, and he was started on a 5-day course of methylprednisolone, 1000 mg daily as a diagnostic and therapeutic maneuver. Clinically, his speech difficulties and confusion resolved almost entirely, and he was able to name, repeat, and follow commands normally. He was able to discontinue phenytoin and valproic acid without recurrence of seizures (either clinically or on EEG). Following pulse-dose steroids, he was discharged on a slow taper of oral prednisone. Repeat imaging in September of 2015 showed marked improvement of all T2 hyperintense lesions and complete resolution of all enhancement (Fig. 2D).

2. Discussion

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) consists of β-amyloid deposition in small and medium arteries of the brain and leptomeninges [1]. It is found in 23–57% of the asymptomatic elderly population and at increased rates in those with dementia and intracerebral hemorrhage [2]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy can more rarely cause an inflammatory reaction, known as CAA-related inflammation (CAA-I). This has historically been described as primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with CAA, cerebral amyloid angiitis, and cerebral amyloid inflammatory vasculopathy [3], [4], [5]. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation presents with subacute cognitive decline, headaches, and seizures rather than the chronic dementia or hemorrhagic strokes classically associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. The mean age at onset is approximately 68 years, significantly younger than for hemorrhagic CAA. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in CAA-I include shifting multifocal white matter T2 hyperintensities abnormalities colocalized with petechial hemorrhages on SWI [6]. Cerebrospinal fluid is typically bland, though protein may be elevated, and more rarely, pleiocytosis has been observed [3]. The APOE ε4/ε4 genotype is present at increased rates — 71% of patients in one case series [6]. Histopathologic findings include amyloid deposition within vessel walls and perivascular, transmural, or intramural inflammation, including perivascular multinucleated giant cells.

Several published cases and case series describe treatment with immunosuppressive therapy, including corticosteroids with or without additional immunosuppressive therapy such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or most commonly cyclophosphamide. Thirty-eight of 53 published cases showed improvement with immunosuppressive treatment, as did Mr. G [3].

Our patient's case was notable for a typically subacute fluctuating clinical course and multifocal fluctuating radiographic findings, classically bland CSF, and a biopsy demonstrating amyloid deposition within artery walls. Inflammatory infiltrate was not seen on biopsy, and this was attributed to the biopsied lesion being an older, “burned out” lesion already undergoing gliosis. Clinically and radiographically, our patient showed the commonly dramatic response to immunomodulatory treatment.

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation is an unusual but highly treatable cause of new-onset seizures in the middle-aged and elderly population and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizures after the age of 40, associated with fluctuating multifocal T2 hyperintensities and petechial hemorrhages on MRI.

References

- 1.Vinters H.V. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke. 1987;18:311–324. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coria F., Rubio I. Cerebral amyloid angiopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1996;22:216–2227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung K.K., Anderson N.E., Hutchinson D., Synek B., Barber P.A. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy related inflammation: three case reports and a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:20–26. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.204180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fountain N.B., Eberhard D.A. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurology. 1996;46:190–197. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harkness K.A., Coles A., Pohl U., Xuereb J.H., Baron J.C., Lennox G.G. Rapidly reversible dementia in cerebral amyloid inflammatory vasculopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:59–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-5101.2003.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eng J.A., Frosch M.P., Choi K., Rebeck G.W., Greenberg S.M. Clinical manifestations of cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:250–256. doi: 10.1002/ana.10810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]