Summary

The main vitamin K‐deficient model, minidose warfarin, is different from the pathological mechanism of vitamin K deficiency, which is a shortage of vitamin K. The objective of this study was to establish a new method of vitamin K‐deficient model combining a vitamin K‐deficient diet with the intragastrical administration of gentamicin in rats. The clotting was assayed by an automated coagulation analyser. The plasma PIVKA‐II was assayed by ELISA. The vitamin K status was detected by an HPLC‐fluorescence system. In the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day group, the rats had undetected vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 in the liver and a prolonged APTT. In the 21‐day group, there was also a prolonged PT and a decrease of the FIX activities. In the 28‐day group, the undetected vitamin K1 and vitamin K2, the prolonged PT and APTT, and the decrease of the FII, FVII, FIX, and FX activities prompted the suggestion that there were serious deficiencies of vitamin K and vitamin K‐dependent coagulation in rats. It is suggested that the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day or 21‐day model can be used for studies related to the status of vitamin K. The vitamin K‐deficient 28‐day model can be applied to research involving both the status of vitamin K and of vitamin K‐dependent coagulation. In conclusion, the combination of a vitamin K‐deficient diet with the administration of gentamicin results in a useful model of vitamin K‐deficieny.

Keywords: animal model, coagulation factor, gentamicin, vitamin K deficiency, warfarin

Introduction

As a cofactor for γ‐glutamyl carboxylase, vitamin K is responsible for the post‐translational modification of glutamate residues in coagulation factors, such as FII, FVII, FIX, FX, protein C and protein S, to γ‐carboxyglutamate. Thus a vitamin K deficiency may result in spontaneous life‐threatening haemorrhages (Dam et al. 1952; Organization W.H 2004). Vitamin K preparations, especially vitamin K1 injection, have been widely used in the treatment of vitamin K deficiency‐induced haemorrhagic diseases, including vitamin K‐related coagulation disorders and malabsorption syndromes, as well as surgery and extensive burn patients who are unable to maintain an adequate oral intake of vitamin K (Helphingstine & Bistrian 2003). Undoubtedly, it is very important to select and establish an appropriate vitamin K‐deficient animal model to study the relevant pathophysiology of vitamin K deficiency, and to evaluate pharmacological effects of vitamin K preparations.

The major animal model establishing vitamin K deficiency is the administration of ‘minidose’ warfarin (Bach et al. 1996), which blocks the reduction of oxidized vitamin K, and prevents the post‐translational carboxylation of FII, FVII, FIX and FX, thereby leading to a decrease of vitamin K actions (Ansell et al. 2008; Patriquin & Crowther 2011). However, the content of vitamin K in the body does not decrease in this model. This model differs from the pathological mechanism of vitamin K deficiency which is a shortage of vitamin K. Moreover, the administration of pharmacological vitamin K1 is influenced by the dose of warfarin (Cushman et al. 2001; Tsu et al. 2012). In the warfarin model, the content of vitamin K to reverse the coagulation function is related to the amount and affinity of warfarin, but not the degree of vitamin K insufficiency. Hence it is not a perfect model to investigate true vitamin K deficiency in the body.

Vitamin K in the body is derived roughly equally from dietary vitamin K1 and intestinal bacteria‐produced vitamin K2 (Conly & Stein 1992; Organization W.H 2004). Komai M, et al. used a vitamin K‐deficient diet for 8 days to establish a primary vitamin K deficiency model, and found that vitamin K‐deficient symptoms did not occur in conventional mice without a prolonged PT and APTT, unless germfree male mice were used in the studies (Komai et al. 1988). Hence, merely cutting off the dietary sources of vitamin K for a few days was not enough to induce vitamin K deficiency. It is reported that changes in stool excretion of phylloquinone and in prothrombin times occurred with no consistent pattern in subjects receiving antibiotics. The median stool excretion of phylloquinone of the subjects was 19 μg/d while taking the hospital diet, and fell to 3 μg/d when a vitamin K‐free diet was administered. Prothrombin times remained within the normal range throughout the study (Allison et al. 1987). Likewise, merely cutting off intestinal bacteria‐produced vitamin K2 cannot induce a complete vitamin K deficiency. Therefore the objective of this study was to establish a new vitamin K deficiency model in rats with a combination of a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the administration of gentamicin. The vitamin K‐deficient diet will eliminate the external supply of vitamin K1; and gentamicin, a powerful and highly sensitive anti‐microbial against E. coli will cut off the supply of vitamin K2 (Ahmed et al. 1997).

Materials and methods

Reagents

Vitamin K1 standard substance (99.6%) and vitamin K2 standard substance (99.9%) were supplied by National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (Beijing, China) and Supelco (Bellefonte, USA) respectively. Vitamin K1 injection was from Cisen Pharmaceutical Co. (Shandong, China). Rat PIVKA‐II ELISA kits and D‐Dimer ELISA kits were purchased from KeyGENBioTECH (Nanjing, China). Prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), FII, FVII, FIX, FX, CaCl2 solution and human standard plasma reagents were obtained from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH (Marburg, Germany).

Animals and drug administration

Sprague‐Dawley rats (280~320 g), half males and half females were purchased from the Animal Center of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China. The animals were maintained in 12 h light/dark cycles under constant temperature (18–26°C) and humidity (30%–70%) and tap water. Rats were randomly divided into 6 groups, and 10 rats in each group: control (standard diet) group; vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups (rats were fed a vitamin K‐deficient diet and 30mg/kg gentamicin was administered intragastrically for 14, 21 and 28 days, respectively); vitamin K‐deficient + vitamin K1 0.01 mg/kg (VKDM/VK 0.01 mg/kg) group and vitamin K‐deficient + vitamin K1 0.1 mg/kg (VKDM/VK 0.1 mg/kg) group (vitamin K‐deficient 28‐day rats were given vitamin K1 injections 0.01 mg/kg and 0.1 mg/kg in the last 7 days respectively). A vitamin K‐deficient diet (steamed bun, Shaan'xi, China) was determined by high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the content of vitamin K1 in the diet was less than 2 ng/g.

Sample preparation

Rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral hydrate 6 h later after the last administration. Blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta, transferred into three 2‐ml sodium citrate tubes, respectively, and immediately protected from light. Then, the plasma was obtained by centrifugation (2500 rpm/10 min) and stored at −20°C until thawed for analysis. The whole livers protected from light were weighed and stored at −20°C until thawed for analysis.

The samples of liver were analysed with some modifications (Haroon & Hauschka 1983; Song et al. 2008; Paroni et al. 2009). The liver (2 g) cut from the right lobe were ground in 1 ml normal saline using a high‐throughput tissue grinder (Ningbo Xingzhi Biotechnology Co., LTD, Zhejiang, China). The macerated tissue was transferred with 6 ml absolute ethanol and 4 ml hexane (Haroon & Hauschka 1983) and placed on a TS‐1000 orbital shaker for 1 h (Haimen Kylin‐Bell Lab Instruments Co., LTD, Jiangshu, China). The mixture was centrifuged (10000 rpm/10 min), and then the cyclohexane was removed under N2 in a water bath at 60°C. To obtain the residue, 1 ml absolute ethyl alcohol was added, mixed vigorously and centrifuged for 5 min at 10000 rpm, and 20 μl of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC column. All the experimental processes were performed in the dark (Qiu et al. 2013).

HPLC system

The liquid chromatography was equipped with reciprocating pumps (LC‐20ADXR, SHIMADZU, Japan), a fluorescence detector (RF‐10AXL, SHIMADZU), a VP‐ODS C18 column (SHIM‐PACK, 150 × 2.0 mm) and an automated injection system (SIL‐20AC, SHIMADZU). The mobile phase was methanol–water containing 20% isopropanol (97:3, v/v), and the column temperature was maintained at 35°C. A constant mobile phase flow rate of 1.0 ml/min was employed throughout the analyses. Vitamin K1 was detected fluorometrically with a detector (λecc 244˜λem 430) after postcolumn online reduction to the hydroquinone form in a 4.6 mm × 5 cm column freshly filled with 98% purity zinc dust (< 10 μm) at each analytical batch (Paroni et al. 2009).

Coagulation assays

PT, APTT, FII, FVII, FIX and FX were determined in this study. Assays were performed for each concentration using an automated coagulation analyser (sysmex CA 7000, sysmex, Milan, Italy) following standard procedures after thawing the samples at 37°C.

Elisa

Under‐γ‐carboxylated prothrombin (PIVKA‐II) ELISA Kit was used to measure rat plasma PIVKA‐II concentrations. All procedures were preformed according to the ELISA instructions and the manufacturers’ instructions (Thermo Electron Corporation, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 18.0). The data were represented as the mean ± SE, and P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Then, anova with least significant difference (LSD) were used to analyse all quantitative data when homogeneity of variance assumptions were satisfied, otherwise anova with Dunnett T3 would be used.

Ethical Approval statement

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications no. 80–23, revised 1996) and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China (Permit Number: XJTU 2011‐0045).

Results

Vitamin K status from diet

The concentration of vitamin K1 in standard diet was 0.64 ± 0.02 μg/g (Figure 1a). However, vitamin K1 was not detected in the vitamin K‐deficient diet and its concentration was below the limit of detection (< 0.3 ng/ml, Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Representative chromatograms of vitamin K status in standard dry food (a) and vitamin K‐deficient food (b).

PIV the KA‐II levels

The concentrations of plasma PIVKA‐II in rats with a vitamin K‐deficient diet and intragastrical administration of gentamicin were significantly higher than those in control group (Figure 2). In the vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day model group, the PIVKA‐II concentration was increased to 17.4 ± 0.3 pg/ml from control of 15.8 ± 0.3 pg/ml (P < 0.01). With the extension of vitamin K‐deficient time, the PIVKA‐II concentrations were further increased. The PIVKA‐II concentrations in the 21‐day and 28‐day groups were significantly elevated to 18.0 ± 0.2 pg/ml and 18.4 ± 0.4 pg/ml respectively (P < 0.01, vs. control).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of PIVKA‐II in plasma. Animals were administrated as follows: control (standard dry food), vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups (rats received a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastric administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 14, 21 and 28 days respectively). The values are shown as the mean ± SE, n = 10. **P < 0.01 vs. control.

PT

The PT was 9.7 ± 0.1 s in the control group. There was no significant difference in PT between the vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day group (10.0 ± 0.3 s) and the control group. After the vitamin K‐deficient diet and the administration of gentamicin for 21 days, the PT was prolonged to 10.2 ± 0.2 s (P < 0.05, vs. control). In the vitamin K‐deficient 28‐day group, PT was prolonged to 14.5 ± 1.4 s (P < 0.01), which is 1.5‐fold one of the control group in rats (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The changes of PT in the vitamin K‐deficient model. Animals were administrated as follows: control (standard dry food), vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day group and 28‐day groups (rats received a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastric administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 14, 21 and 28 days respectively). The values are shown as the mean ± SE, n = 10. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control.

APTT

The APTT was 19.4 ± 0.8 s in controls, but prolonged in all other groups (Figure 4). The prolonged APTT in the 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups were about 1.5 times those found in the controls (14‐day: 28.3 ± 1.4 s, 21‐day: 28.1 ± 1.8 s, 28‐day: 28.8 ± 2.0 s, P < 0.01, vs. control respectively). Moreover, there was no significant difference in APTT between the vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day model groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

The changes of APTT in the model of vitamin K deficiency. Animals were administrated as follows: control (standard dry food), vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups (rats received a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastric administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 14, 21 and 28 days respectively). The values are shown as the mean ± SE, n = 10. **P < 0.01 vs. control.

Coagulant factor activity

The FII, FVII, FIX and FX activities in plasma appeared to have changed in the vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day group. However, this was not statistically significant. In the vitamin K‐deficient 21‐day group, the FIX activity decreased to 47.5 ± 3.7% (vs. control 62.7 ± 4.7%, P < 0.05). Factor activities were significantly lower in the 28‐day model group (FII 30.5 ± 4.8%, FVII 106.2 ± 22.2%, FIX 35.1 ± 5.9%, FX 20.2 ± 4.7%, respectively) than in the control group (FII 69.3 ± 5.6%, FVII 218.5 ± 10.7%, FIX 62.7 ± 4.7%, FX 47.0 ± 2.5%, P < 0.01) (Figure 5a‐d).

Figure 5.

Levels of coagulant factor activity in the vitamin K‐deficient model groups. a: FII activity; b: FVII activity; c: FIX activity; d: FX activity. Animals were administrated as follows: control (standard dry food), vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups (rats received a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastric administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 14, 21 and 28 days respectively). The values are shown as the mean ± SE, n = 10. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control.

Vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 levels in livers

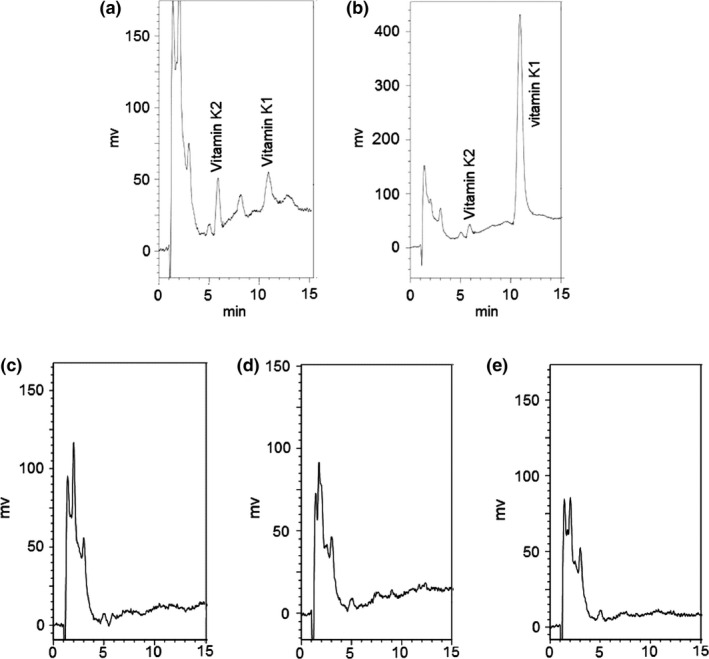

The peaks of vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 were, respectively, eluted within about 10.5 min and 5.8 min under the described analytical conditions (Figure 6a and b). The limit of detection was 0.3 ng/ml and the limit of quantitation was 1.0 ng/ml both for vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 in the samples. The reproducibility of the detection in liver samples was studied with 3 repeated injections of 3 sample solutions containing the analytes at 2 concentrations, 62.5 and 250.0 ng/ml. The relative standard deviation was less than 0.8%. In the control group, the content of vitamin K1 was 10.8 ± 0.8 ng/g, and the amount of vitamin K1 was 74.3 ± 8.4 ng in livers. The content of vitamin K2 was 17.7 ± 2.2 ng/g, and the amount of vitamin K2 was 116.3 ± 15.4 ng in livers. However, the contents of vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 in livers were below the limit of detection and were not detectable in the vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups (Figure 6c‐f).

Figure 6.

Representative chromatograms of vitamin K from liver samples. a: liver sample of normal rats; b: normal liver sample with 250 ng/ml vitamin K1 standard substance; c: liver samples from rats with a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastrical administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 14 days; d: liver samples from rats with the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency for 21 days; e: liver samples from rats with a diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency for 28 days.

The effect of vitamin K1 injection on vitamin K‐deficient model rats

After the administration of the 0.01 and 0.1 mg/kg vitamin K1 injection for 7 days, the activities of the coagulation factors were increased in the vitamin K‐deficient (28‐day) model rats. The PT and APTT returned to normal levels in the VKDM/VK 0.01 mg/kg group (PT: 9.9 ± 0.1 s vs. control 9.7 ± 0.1 s, P > 0.05, vs. 28‐day group 14.5 ± 1.4 s, P < 0.01; APTT: 21.6 ± 1.1 s vs. control 19.4 ± 0.8 s, P > 0.05, vs. 28‐day group 28.7 ± 2.0 s, P < 0.01) (Figure 7a, b). Correspondingly, FII activities were restored to the normal level of 65.8 ± 4.0% from 30.5 ± 4.8% (P < 0.01, Figure 7b). FVII activities returned back to the normal level of 195.2 ± 8.1% from 106.2 ± 22.2% (P < 0.01, Figure 7b). FIX activities were also back to the normal level (67.2 ± 4.2% vs. control 62.7 ± 4.7%, P > 0.05) (Figure 7b). Meanwhile, FX activities were increased to 38.1 ± 3.5% from 20.2 ± 4.7% (P < 0.05), but did not reach the normal level (P < 0.01, Figure 7b). In the VKDM/VK 0.1 mg/kg group, all coagulation factors including PT, APTT, FII, FVII, FIX and FX activities returned to normal levels, and there was no significant difference in coagulation factor activities between the VKDM/VK 0.1 mg/kg group and the control group (Figure 7a and b).

Figure 7.

The effect of vitamin K1 on the coagulant levels in the vitamin K‐deficient model rats. a: The changes of PT and APTT; b: The changes of the coagulant factors activities. Animals were administrated as follows: control (standard dry food), VKDM group (rats received a vitamin K‐deficient diet and the intragastric administration of 30 mg/kg gentamicin for 28 days); VKDM/VK 0.01 mg/kg and 0.1 mg/kg group (vitamin K‐deficient 28‐day rats were intravenously administered vitamin K1 injections 0.01 mg/kg and 0.1 mg/kg in the last 7 days respectively). The values are shown as the mean ± SE, n = 10. **P < 0.01 vs. control; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 vs. VKDM.

Discussion

Vitamin K deficiency affects both the intrinsic and extrinsic clotting cascade and can result in prolonged clotting times and haemorrhage (Burke 2013). With the change in vitamin K status in the body, the activities of FII, FVII, FIX, FX, protein C and protein S, which need γ‐carboxyglutamate, will be impacted, resulting in prolonged PT and APTT.

In the setting of vitamin K deficiency, an abnormal form of coagulation factor II, also referred to as ‘protein induced by vitamin K absence’ under‐γ‐carboxylated prothrombin (PIVKA‐II), is released into the bloodstream and can be directly measured (Gopakumar et al. 2010). PIVKA‐II is unique in that it can help identify early or subclinical vitamin K deficiency. Furthermore, because of the long half‐life, PIVKA‐II can be used to identify vitamin K deficiency on retrospective analysis (Clarke & Shearer 2007). The high plasma PIVKA‐II levels in the three vitamin K‐deficient groups (14‐day, 21‐day and 28‐day groups) thus implied that there was a vitamin K deficiency in the rats.

The prolonged APTT and PT and the decrease of coagulation factor activities indicate that the resource of vitamin K is deficient. APTT is a screening test for factors II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII of the intrinsic and common pathways (Proctor & Rapaport 1961). In the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K‐deficient 14‐day and 21‐day groups, the significantly prolonged APTT was related to the additive effects of the marginal fall in the FII, FIX, and FX activities in plasma. In the vitamin K‐deficient 28‐day group, APTT was prolonged with the decrease in FII, FIX, and FX activities. PT is a screening test for factors II, V, VII and X of the extrinsic and common pathways (Rizzo et al. 2008). PT was prolonged in the 21‐day group which was owing to the additive effects of the marginal fall in the FII, FVII, and FX activities. At 28 days the prolonged PT was aggravated by the decrease in FII, FVII and FX activities. The prolonged PT occurred later than the APTT because of the earlier decrease in FIX activity and the lesser abundance of FVII in plasma compared to other coagulation factors (Dahlback 2000). Besides, the decrease in the coagulation factors was always later than the prolonged APTT and PT and the shortage of vitamin K in body.

The liver is an effective storage organ for vitamin K (Organization W.H 2004). Therefore, the amount of vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 in liver is a true reflection of the vitamin K status. The undetectable vitamin K1 and vitamin K2 in the livers of rats given the vitamin K‐deficient diet and gentamicin directly mirrors the deficiency of vitamin K in body.

The administration of the vitamin K1 injection for 7 days improved coagulation factor activities and PT and APTT in vitamin K deficienct rats, suggesting that the coagulation functions are related to the status of vitamin K in the model. On the other hand, the dose of vitamin K1 to improve vitamin K deficiency in the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency model is obviously lower than in the warfarin vitamin K deficiency model. It was reported that 100 mg/kg vitamin K1 diet failed to reverse the coagulation function of 10 mg/kg warfarin (Haffa et al. 2000). After the subjects were given warfarin 1 mg/d for 14 d, 1 mg vitamin K1/d was administrated for 5 days to reverse the acquired vitamin K deficiency, which altered plasma concentrations of prothrombin, but not PT, VII activity, prothrombin F‐1·2 concentrations and under‐γ‐carboxylated prothrombin (Bach et al. 1996). The amount of 1 mg vitamin K1 for adults is equivalent to the dose of 0.1 mg/kg for rats. The dose of vitamin K1 failed to reverse warfarin‐induced vitamin K deficiency, while the same dose improved PT, APTT and coagulation levels in rats with the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency. The warfarin‐induced vitamin K deficiency model increases the vitamin K that is required to reverse the acquired vitamin K deficiency and does not reflect the true status of vitamin K in the body. Therefore, it is not a perfect model to investigate true vitamin K deficiency.

In conclusion, the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency model is the more optimum one. Thus it is suggested that rats with the vitamin K‐deficient diet and the administration of gentamycin for 14 or 21 days should be used as a vitamin K‐deficient model in studies relating to the status of vitamin K itself even if is not ideal for vitamin K‐dependent coagulation. Rats that have been subjected to the diet‐ and gentamicin‐induced vitamin K deficiency for 28 days can be regarded as a vitamin K‐deficient model which is suitable for research involving both the status of vitamin K and vitamin K‐dependent coagulation factors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authorship

YXC conceived and designed the experiment. YNM, XX, DZL, NNP, YBZ and LHL performed the study. YNM analysed the data. YXC contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. YNM prepared the manuscript and figures. YXC and YNM revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shaanxi Province Science and Technology Research and Development Programs of China (2012SP2‐06). We would like to thank Zongchang Zhang, Rong Wang, Ruihong Yu and Sen Li at Department of Pharmacology, Xi'an Jiaotong University College of Medicine, for their kind help and support with the experiments.

References

- Ahmed A., Paris M.M., Trujillo M. et al (1997) Once‐daily gentamicin therapy for experimental Escherichia coli meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41, 49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P.M., Mummah‐Schendel L.L., Kindberg C.G. et al (1987) Effects of a vitamin K‐deficient diet and antibiotics in normal human volunteers. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 110, 180–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell J., Hirsh J., Hylek E. et al (2008) Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 133, 160S–198S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach A.U., Anderson S.A., Foley A.L. et al (1996) Assessment of vitamin K status in human subjects administered “minidose” warfarin. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 894–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C.W. (2013) Vitamin K deficiency bleeding: overview and considerations. J Pediatr Health Care. 27, 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P. & Shearer M.J. (2007) Vitamin K deficiency bleeding: the readiness is all. Arch. Dis. Child. 92, 741–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conly J.M. & Stein K. (1992) The production of menaquinones (vitamin K2) by intestinal bacteria and their role in maintaining coagulation homeostasis. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 16, 307–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman M., Booth S.L., Possidente C.J. et al (2001) The association of vitamin K status with warfarin sensitivity at the onset of treatment. Br. J. Haematol. 112, 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlback B. (2000) Blood coagulation. Lancet 355, 1627–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam H., Dyggve H., Larsen H. et al (1952) The relation of vitamin K deficiency to hemorrhagic disease of the newborn. Adv. Pediatr. 5, 129–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopakumar H., Sivji R. & Rajiv P.K. (2010) Vitamin K deficiency bleeding presenting as impending brain herniation. J Pediatr Neurosci 5, 55–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffa A., Krueger D., Bruner J. et al (2000) Diet‐ or warfarin‐induced vitamin K insufficiency elevates circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin without altering skeletal status in growing female rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 15, 872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon Y. & Hauschka P.V. (1983) Application of high‐performance liquid chromatography to assay phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in rat liver. J. Lipid Res. 24, 481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helphingstine C.J. & Bistrian B.R. (2003) New Food and Drug Administration requirements for inclusion of vitamin K in adult parenteral multivitamins. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 27, 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komai M., Shirakawa H. & Kimura S. (1988) Newly developed model for vitamin K deficiency in germfree mice. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 58, 55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization W.H , Nations F.a.A.O.o.t.U . (2004) Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition. World Health Organization; 108–129. [Google Scholar]

- Paroni R., Faioni E.M., Razzari C. et al (2009) Determination of vitamin K1 in plasma by solid phase extraction and HPLC with fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 877, 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriquin C. & Crowther M. (2011) Treatment of warfarin‐associated coagulopathy with vitamin K. Expert Rev Hematol. 4, 657–665 quiz 666‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R.R. & Rapaport S.I. (1961) The partial thromboplastin time with kaolin. A simple screening test for first stage plasma clotting factor deficiencies. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 36, 212–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu S., Liu Z., Hou L. et al (2013) Complement activation associated with polysorbate 80 in beagle dogs. Int. Immunopharmacol. 15, 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo F., Papasouliotis K., Crawford E. et al (2008) Measurement of prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) on canine citrated plasma samples following different storage conditions. Res. Vet. Sci. 85, 166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q., Wen A.D., Ding L. et al (2008) HPLC‐APCI–MS for the determination of vitamin K1 in human plasma: method and clinical application. J. Chromatogr. B 875, 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsu L.V., Dienes J.E. & Dager W.E. (2012) Vitamin K dosing to reverse warfarin based on INR, route of administration, and home warfarin dose in the acute/critical care setting. Ann. Pharmacother. 46, 1617–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]