Abstract

Transcriptional heterogeneity is extensive in the genome, and most genes express variable transcript isoforms. However, whether variable transcript isoforms of one gene are regulated by common promoter elements remain to be elucidated. Here, we investigated whether isoform promoters of one gene have separated DNA signals for transcription and translation initiation. We found that TATA box and nucleosome-disfavored DNA sequences are prevalent in distinct transcript isoform promoters of one gene. These DNA signals are conserved among species. Transcript isoform has a RNA-determined unstructured region around its start site. We found that these DNA/RNA features facilitate isoform transcription and translation. These results suggest a DNA-encoded mechanism by which transcript isoform is generated.

Promoter DNA sequence features are indicative of gene activity1,2. DNA consensus sequences in promoters recruit general transcription factors (GTF) and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to initiate transcription. The sequence context affects selection of transcription start sites (TSS) and transcriptional activity3,4,5. The best-known consensus sequence element is the TATA box, bound by TATA binding protein (TBP)6. Experimental evidence indicates that variation of the TATA box sequence results in differences in promoter activity levels7,8,9. DNA sequence also affects chromatin structure, the basic unit of which is the nucleosome10,11. The DNA-encoded nucleosomal organization in promoter regions plays a role in regulation of gene transcriptional activity12,13. Rigid DNA enriched of A/T nucleotides is prevalent in upstream regions of TSS, inhibiting DNA packaging of nucleosomes and facilitating the recruitment of Pol II and GTF for transcription14,15.

The dynamic usage of transcript isoforms is a pervasive mechanism in gene regulation. Its functions have been extensively studied for several individual genes. The diversity in transcript isoforms, mediated through alternate promoter usage and alternative polyadenylation, plays a role in messenger RNA transcription, stability and translation16,17,18,19. For example, p53 isoforms with alternative promoters are differentially expressed in a tissue-dependent manner, controlling cell proliferation20,21. Transcript isoforms are also produced by alternative splicing, encoding proteins that differ in localization or function22,23. For example, two alternatively spliced variants of TRPM3, which encodes a type of cation-selective channel in human, target different ions24. More recent studies have revealed the importance of transcript isoforms in human diseases such as cancer. The M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase promotes cancer metabolism and tumour growth compared with another isoform M1 25.

Human genes have multiple TSSs, which have epigenetic and genomic relevance26. However, previous studies have found that most genes have only one major TSS in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by RNA sequencing27,28. We referred to the transcript initiated from the major TSS as main isoform. A recent study has jointly sequenced the 5′ and 3′ ends of each RNA molecule to measure transcript isoforms in Saccharomyces cerevisiae29. This new sensitive technique revealed that most yeast genes have various TSSs: an average of 26 transcript isoforms covering the intact ORF were expressed per protein-coding gene. Most of these TSSs have not been discovered by RNA sequencing in previous studies27,28. These newly discovered TSSs are likely to be minor TSSs, that is, the proportion of transcripts initiated from minor TSSs is lower than those initiated from major TSSs. We referred to the transcripts initiated from minor TSSs as other isoforms. It is interesting to examine whether DNA consensus sequences also exist in upstream regions of other isoforms, implying that isoform transcription may be encoded in DNA sequence. If this is true, it is more likely that the extensive isoform diversity has functional relevance. In this study, using genome-wide isoform data in yeast29, we revealed DNA signals in upstream regions of other isoforms. These sequence features enhance mRNA and protein expression levels, moreover, are conserved among species.

Results

TATA box is enriched in upstream of other isoforms

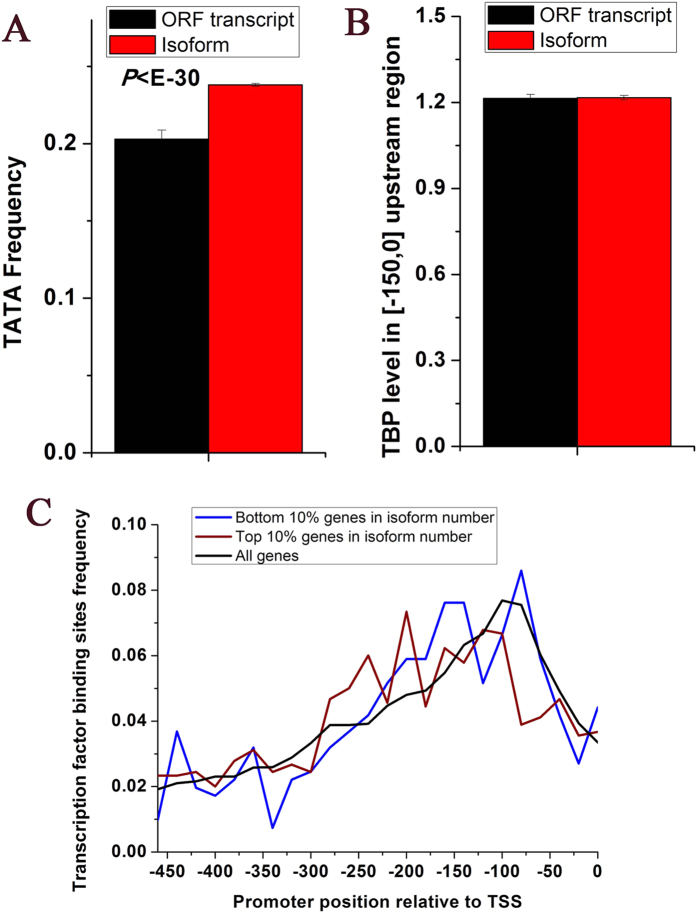

We used genome-wide identified transcript isoforms covering the intact ORF in S. cerevisiae29. First, we examined the enrichment of TATA box upstream of other isoforms. TATA box generally locates within 150 bp upstream of gene, which recruits pre-initiation complex (PIC) for transcription initiation6. For each isoform, we searched the TATA box TATAWAWR consensus30 in its 150 bp upstream region. We found that consensus TATA box frequency of other isoforms is significantly higher than that of main isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 1A). This observation might be confused by the shared upstream region between other isoforms and main isoforms. We restricted the analysis to other isoforms whose 150 bp upstream region has no overlap with the 150 bp upstream region of their corresponding main isoforms. Similar result could be observed (Figure S1), albeit with less statistical significance.

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 1A). This observation might be confused by the shared upstream region between other isoforms and main isoforms. We restricted the analysis to other isoforms whose 150 bp upstream region has no overlap with the 150 bp upstream region of their corresponding main isoforms. Similar result could be observed (Figure S1), albeit with less statistical significance.

Figure 1. A canonical organization of transcription machinery upstream of other isoforms.

(A) Average values that correspond to TATA frequency in upstream [−150,0] region are shown for other isoforms (transcript isoforms) (N = 162,379) and main isoforms (ORF transcripts) (N = 4,759). (B) Average values that correspond to PIC occupancy level in upstream [−150,0] region are shown for other isoforms (N = 19,808) and main isoforms (N = 4,759). (C) Distribution of the promoter positions of transcription factor binding sites in the three gene classes: genes with most other isoforms (N = 475), genes with least other isoforms (N = 475), and all genes (N = 4,759). Error bars in (A,B) were calculated by bootstrapping. The statistical significant values calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated.

Second, we asked whether the observed TATA box is associated with transcription initiation. To this end, we tested whether PIC is enriched in upstream regions of other isoforms. To avoid the shared PIC between other isoforms and main isoforms, we restricted the analysis to other isoforms whose 150 bp upstream region has no overlap with the 150 bp upstream region of their corresponding main isoforms. We found that TBP occupancy in upstream region is comparable between other isoforms and main isoforms ( Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 1B), indicating that TATA box in upstream region of other isoforms can recruit TBP.

Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 1B), indicating that TATA box in upstream region of other isoforms can recruit TBP.

Third, we examined the relationship between other isoforms and transcription factor binding site (TFBS). TFBSs are generally enriched 50–150 bp upstream of the gene in S. cerevisiae15. However, TFBSs are highly localized in 200–300 bp upstream of greatly other isoform-enriched genes (Fig. 1C). Considering that the start sites of other isoform are upstream of the start codon, this shift in TFBS distribution reflects the role of upstream TFBSs in transcription initiation of other isoforms.

Other isoforms show low DNA-encoded nucleosome occupancy in upstream regions

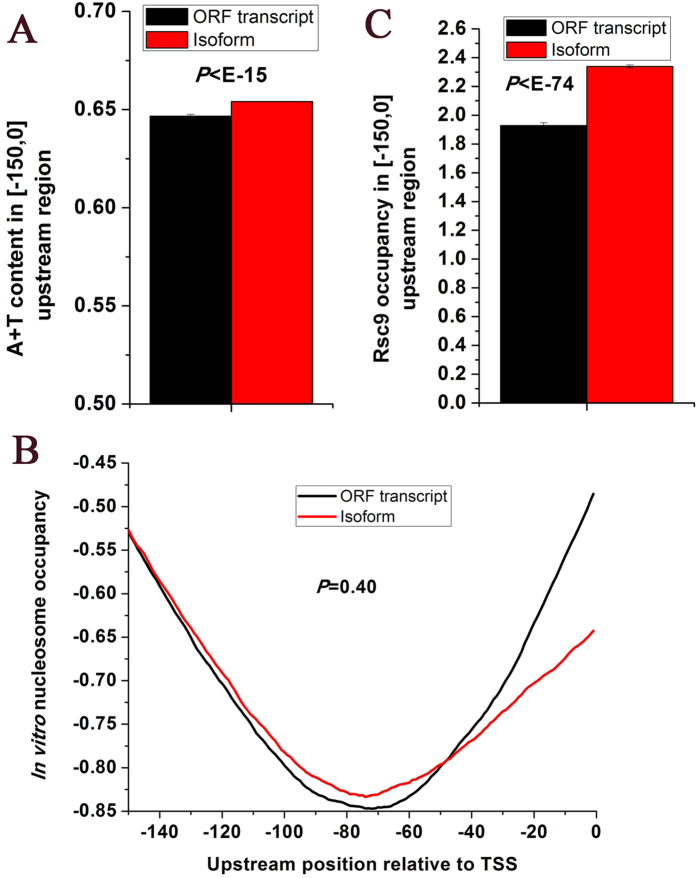

Intrinsic DNA sequence is an important determinant of nucleosome positioning. Nucleosome positioning can be predicted by DNA sequence31,32. Yeast genes generally contain high A/T content in 150 bp upstream regions33,34, which inherently inhibit nucleosome formation35,36. Nucleosome positioning upstream of genes is a barrier for recruitment of GTF and Pol II. Depletion of the nucleosome positioning can enhance transcription. We asked whether other isoforms have similar DNA-encoded nucleosomal organization in their upstream regions. First, we found that other isoforms have higher A/T content in upstream regions than main isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2A). Similar observation could be reproduced when using another criterion of calculating A/T content (Figure S2). Second, we examined nucleosome occupancy upstream of other isoforms. Genome-wide occupancy of nucleosomes assembled on purified yeast genomic DNA was measured with 1-bp resolution14. This in vitro nucleosome map is determined only by the intrinsic sequence preferences of nucleosomes. Other isoforms show comparable in vitro nucleosome occupancy in upstream regions with main isoforms (

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2A). Similar observation could be reproduced when using another criterion of calculating A/T content (Figure S2). Second, we examined nucleosome occupancy upstream of other isoforms. Genome-wide occupancy of nucleosomes assembled on purified yeast genomic DNA was measured with 1-bp resolution14. This in vitro nucleosome map is determined only by the intrinsic sequence preferences of nucleosomes. Other isoforms show comparable in vitro nucleosome occupancy in upstream regions with main isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2B). Similar results could be reproduced when using another independent in vitro nucleosome occupancy data37 (

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2B). Similar results could be reproduced when using another independent in vitro nucleosome occupancy data37 ( , Mann-Whitney U-test). However, other isoforms show higher in vivo nucleosome occupancy than main isoforms (Figure S3). Note that experimentally measured nucleosome occupancy in vivo is the average among cell populations. Nucleosome positioning might be transiently remodeled to allow the binding of PIC to DNA for transcription initiation. A recent study has found that AT-rich sequences facilitate the remodeling of nucleosomes by the RSC chromatin remodeling complex in gene promoters38. Indeed, other isoforms have significantly higher Rsc9 occupancy in upstream regions than main isoforms (

, Mann-Whitney U-test). However, other isoforms show higher in vivo nucleosome occupancy than main isoforms (Figure S3). Note that experimentally measured nucleosome occupancy in vivo is the average among cell populations. Nucleosome positioning might be transiently remodeled to allow the binding of PIC to DNA for transcription initiation. A recent study has found that AT-rich sequences facilitate the remodeling of nucleosomes by the RSC chromatin remodeling complex in gene promoters38. Indeed, other isoforms have significantly higher Rsc9 occupancy in upstream regions than main isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2C).

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Low DNA-encoded nucleosome occupancy upstream of other isoforms.

(A) Average values that correspond to A + T content in upstream [−150,0] region are shown for other isoforms (N = 19,808) and main isoforms (N = 4,759). (B) Average in vitro nucleosome occupancy profiles within upstream [−150,0] region are shown for other isoforms (N = 19,808) and main isoforms (N = 4,759). (C) Average values that correspond to chromatin remodeler Rsc9 occupancy level in upstream [−150,0] region are shown for other isoforms (N = 19,808) and main isoforms (N = 4,759). Error bars in (A,C) were calculated by bootstrapping. The statistical significant values calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated.

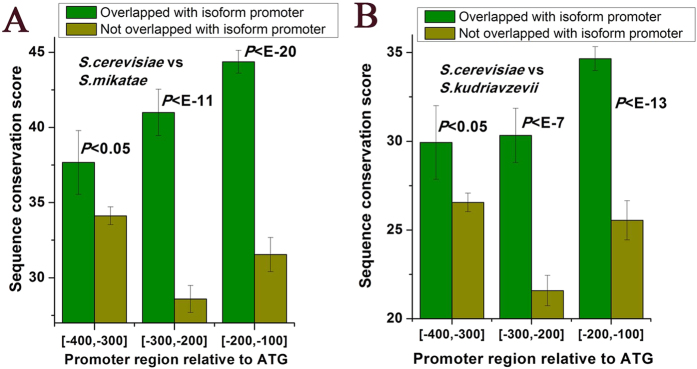

DNA sequence upstream of other isoforms is conserved among species

An interesting question is to ask whether the observed DNA sequence features upstream of other isoforms have roles in regulation. If this is the case, DNA sequence upstream of other isoforms should be under evolutionary constraint to maintain its function. We classified gene promoter regions not covered by isoforms into two catalogues: one covered by 150 bp upstream region of isoform, and the other not. DNA sequence is more conserved among yeast species in former region (Fig. 3). In addition, DNA sequence conservation in gene promoters shows no correlation with transcriptional activity (Figure S4), ruling out the possibility that our observation is biased by transcriptional activity.

Figure 3. DNA sequence upstream of other isoforms is conserved among species.

We performed global alignment on promoter sequences (upstream of start codon) between orthologous genes, and used the resulting alignment score as sequence conservation score. Average values that correspond to sequence conservation score are shown for gene promoters covered by isoform promoters (150 bp upstream) and those not covered by isoform promoters. As [−100, 0] in all gene promoters are covered by isoform promoters, we excluded this region for analysis. Promoter is divided into three bins. (A) Orthologous genes between S. cerevisiae and S. mikatae. (B) Orthologous genes between S. cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii. Error bars were calculated by bootstrapping. The statistical significant values calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated.

Other isoforms are associated with increased gene expression

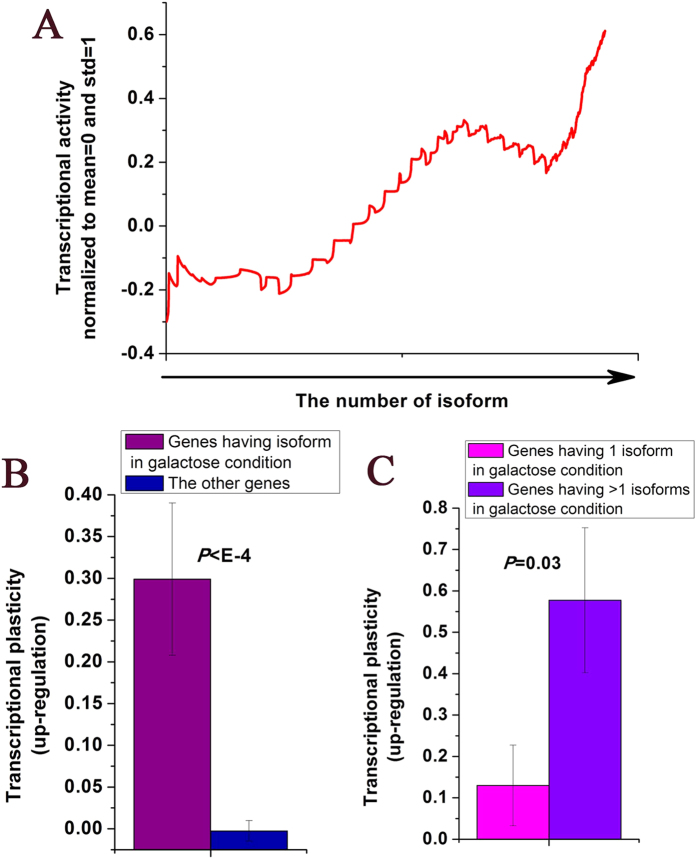

As we have shown that upstream DNA sequence could facilitate transcription of other isoforms, we asked whether genes having other isoforms show high gene expression levels. Indeed, gene transcriptional activity in YPD medium tend to increase with the number of other isoforms (Fig. 4A). Similar results could be reproduced when using another independent transcriptional activity data28 (Figure S5). We next tested whether this relationship could be observed in other cellular conditions. We identified genes having no other isoform in YPD medium but having other isoform when the yeast was grown in a galactose medium. These genes show higher degree of transcriptional up-regulation in various cellular conditions relative to YPD medium ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 4B). Moreover, high degree of up-regulation is associated with high number of other isoforms (

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 4B). Moreover, high degree of up-regulation is associated with high number of other isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 4C). Similar results could be reproduced when using another independent transcriptional plasticity data39 (Figure S6). A previous study has found that genes with high upstream nucleosome occupancy close to the start codon show higher degree of transcriptional up-regulation in various cellular conditions, and referred these genes as occupied proximal-nucleosome (OPN) genes40. The genes (N = 199) we identified above, which have no other isoform in YPD medium but have at least one other isoform in galactose condition, only show small overlap (12 genes) with OPN genes (N = 544) (hypergeometric

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 4C). Similar results could be reproduced when using another independent transcriptional plasticity data39 (Figure S6). A previous study has found that genes with high upstream nucleosome occupancy close to the start codon show higher degree of transcriptional up-regulation in various cellular conditions, and referred these genes as occupied proximal-nucleosome (OPN) genes40. The genes (N = 199) we identified above, which have no other isoform in YPD medium but have at least one other isoform in galactose condition, only show small overlap (12 genes) with OPN genes (N = 544) (hypergeometric  ). Moreover, these genes show comparable degree of transcriptional up-regulation with OPN genes (

). Moreover, these genes show comparable degree of transcriptional up-regulation with OPN genes ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Figure S7). These results suggest that genes with other isoforms are up-regulated in a different mechanism from OPN genes.

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Figure S7). These results suggest that genes with other isoforms are up-regulated in a different mechanism from OPN genes.

Figure 4. Other isoforms are associated with increased gene expression.

(A) Genes were ordered by their numbers of other isoforms, and a sliding window (window size of 300 genes) is shown for transcriptional activity, which is normalized by subtracting their means and dividing by their standard deviations. (B) Average values that correspond to transcriptional plasticity (up-regulation) are shown for genes having no other isoform in YPD medium but having at least one other isoform in galactose condition, and the other genes. (C) Average values that correspond to transcriptional plasticity (up-regulation) are shown for genes having no other isoform in YPD medium but having one other isoform in galactose condition, and genes having no other isoform in YPD medium but having more than one other isoforms in galactose condition. Error bars in (B,C) were calculated by bootstrapping. The statistical significant values calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated.

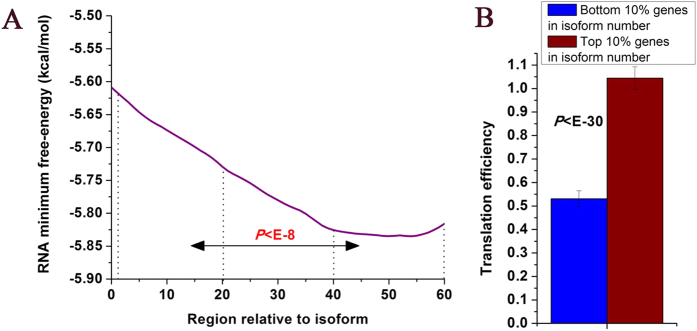

Other isoforms are associated with increased translation efficiency

RNA structure has critical roles in regulation of translation. mRNA generally has unstructured (accessible) region immediately upstream of the start codon, which might facilitate ribosome binding and translation initiation41,42. We asked whether other isoforms also have unstructured region near their start sites. As experimentally measured RNA structure data is not available for other isoforms, we instead used RNA free-energy calculated solely by RNA sequence. RNA free-energy is negatively correlated with RNA structure: High RNA free-energy corresponds to an RNA unstructured region. RNA encodes relatively unstructured region near start sites of other isoforms ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 5A). We tested whether this RNA structure has consequent effects on translation. Indeed, using genome-wide ribosome profiling data43, we found that genes having more other isoforms show higher translation efficiency (

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 5A). We tested whether this RNA structure has consequent effects on translation. Indeed, using genome-wide ribosome profiling data43, we found that genes having more other isoforms show higher translation efficiency ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Figs. 5B and S8 and S9). As long mRNAs can have more ribosomes than short mRNAs, we examined whether our result is biased by this property. However, we found that genes having more other isoforms have shorter mRNA (

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Figs. 5B and S8 and S9). As long mRNAs can have more ribosomes than short mRNAs, we examined whether our result is biased by this property. However, we found that genes having more other isoforms have shorter mRNA ( , Mann-Whitney U-test, Figure S10).

, Mann-Whitney U-test, Figure S10).

Figure 5. Other isoforms are associated with increased translation efficiency.

(A) Average RNA minimum free-energy profile computed by RNA sequence alone is shown for other isoforms. The profile is smooth by a 15 bp sliding window. The statistical significant difference between [0,20] and [40,60] regions calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated. (B) Average values that correspond to translation efficiency are shown for genes with most other isoform and genes with least other isoform. Error bars were calculated by bootstrapping. The statistical significant values calculated from Mann-Whitney U-test were indicated.

Discussion

In this study, we performed a genome-wide analysis and investigated into the cause and consequence of transcript isoforms. We found that a gene’s main isoform and other isoforms, produced from alternative transcriptional start sites, show similar patterns within their DNA promoter sequences. In particular, we found TATA box features, nucleosome-disfavored sequence signals, and DNA-encoded RNA unstructured regions near the respective transcriptional start sites. These patterns facilitate isoform transcription and translation. Main results in this study could be reproduced using another independent TSS data28 (Figures S11–S13). These results indicate that prevalent other isoforms are encoded in DNA sequence, and have implications in isoform function inference. As function of most transcript isoforms is unknown, it is interesting to examine whether isoform function can be inferred from its DNA context.

One key finding in this study is that DNA sequence upstream of other isoforms is conserved among species. DNA signal facilitating isoform transcription is under selective constraint. Transcription initiation includes two steps: chromatin remodeling and PIC assembly. Although there is no low nucleosome occupancy upstream of isoform, the intrinsic nucleosome-disfavored DNA signals upstream of isoform could facilitate nucleosome repositioning by chromatin remodelers. TATA box upstream of isoform recruit PIC for transcription initiation.

Genes with more other isoforms have more TSSs (Figure S14). Multiple TSSs upstream of ORF enhances the chance of transcription initiation, thereby genes with more other isoforms show high transcriptional activity. Some genes utilize this strategy in response of environmental condition changes. To the best of our knowledge, this is a new strategy ever revealed. As we have shown that isoform generation is encoded in DNA sequence, their response of environmental condition changes might be also encoded in DNA sequence. Further experiments will be needed to examine why these genes have no other isoform in normal condition.

Methods

Data preparation

Yeast genome-wide transcript isoform coordinate data in YPD medium were taken from Pelechano et al.29. Genome-wide occupancy data for PIC (including TBP, TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, TFIIH and TFIIK) were taken from Rhee et al.30. Average PIC occupancy level in upstream [−150,0] region is calculated for each isoform. Genome-wide binding data corresponding to 203 TFs were taken from MacIsaac et al.44. A P value cutoff of 0.001 was used to define the set of genes bound by a particular TF. Genome-wide nucleosome occupancy data in vivo and in vitro measured with high resolution were taken from Kaplan et al.14. Average nucleosome occupancy level in upstream [−150,0] region is calculated for each isoform. Genome-wide chromatin remodeler Rsc9 occupancy data measured with high resolution were taken from Venters et al.45. Average Rsc9 occupancy level in upstream [−150,0] region is calculated for each isoform. The list of OPN genes were taken from Tirosh et al.40. Genome-wide gene transcriptional activity (transcription rate) data were taken from Holstege et al.46. Genome-wide gene translation efficiency (ribosome/mRNA) data were taken from Artieri et al.43. All these data in form of processed data were downloaded from supplemental materials or supplemental websites of their original literatures. All data in this study were measured in YPD medium unless indicated.

Definition of other isoform

1) We restricted the analysis to isoforms covering the whole ORF. In this way, these isofroms are transcripts of ORFs, and are not noise of transcription. ORF and their coordinate (start and stop codons) data were taken from Saccharomyces Genome Database47. 2) We excluded isoforms whose coordinates are the same as major TSS of their covering ORF. In this way, we can separate isoform transcripts initiated from minor TSSs (other isoform) from isoform transcripts initiated from major TSSs (main isoform). Experimentally validated TSS data for ORF were taken from Miura et al.27. In this study, we used isoforms identified by 1) and 2) as other isoforms and compared them with main isoforms (i.e. ORF transcripts in this study, Figure S15).

Calculation of promoter sequence conservation

We classified gene promoter regions not covered by isoforms into two catalogues: one covered by 150 bp upstream region of isoforms, and the other not. Orthologous genes between S. cerevisiae and S. mikatae, between S. cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii were taken from Wapinski et al.48. We performed global alignment (function ‘nwalign’ in software ‘Matlab’ version R2012b) on promoter sequences between orthologous genes, and used the resulting alignment score as sequence conservation score. We then used these scores to compare between the two promoter catalogues identified above.

Calculation of transcriptional plasticity

We compiled available gene expression data from the Stanford Microarray Database49, a total of 1,260 published microarray experiments for 6,260 genes in various cellular conditions. For each gene, we calculated the average of the squared positive expression level from the 1,260 experiments, and defined the normalized resulting value as transcriptional plasticity (up-regulation), which reflected the dynamic extent of its expression level in various conditions.

Calculation of RNA free energy

The minimum free energy for the RNA sequence was computed as previous studies50,51. For each of sliding windows (50 bp long, 1 bp step) within the transcript isoform, we computed the minimum free energy (function ‘rnafold’ in software ‘Matlab’ version R2012b) in that window, and assigned it to the first nucleotide of the window.

Statistical methods

Given two samples of values, the Mann-Whitney U-test (function ‘ranksum’ in software ‘Matlab’ version R2012b) is designed to examine whether they have equal medians. The main advantage of this test is that it makes no assumption that the samples are from normal distributions. Error bars in figures were calculated by bootstrapping: Data points in a data set are randomly resampled to create 1000 different data sets (each has the same number of data points as the original data set, function ‘bootstrp’ in software ‘Matlab’ version R2012b), and the mean value is computed for each data set, and standard deviation is computed for the 1000 mean values.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Dai, Z. et al. DNA signals at isoform promoters. Sci. Rep. 6, 28977; doi: 10.1038/srep28977 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant 61202343), and also by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant 13lgpy06).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Z.D. implemented the algorithms and carried out the experiments. Z.D. also designed the study, analyzed the results and drafted the manuscript. X.D. and Y.X. participated in the analysis and discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Faitar S. L., Brodie S. A. & Ponticelli A. S. Promoter-specific shifts in transcription initiation conferred by yeast TFIIB mutations are determined by the sequence in the immediate vicinity of the start sites. Mol Cell Biol. 21, 4427–4440, 10.1128/mcb.21.14.4427-4440.2001 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furter-Graves E. M. & Hall B. D. DNA sequence elements required for transcription initiation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe ADH gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet : MGG. 223, 407–416 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. & Struhl K. Yeast mRNA initiation sites are determined primarily by specific sequences, not by the distance from the TATA element. EMBO J. 4, 3273–3280 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S., Hoar E. T. & Guarente L. Each of three “TATA elements” specifies a subset of the transcription initiation sites at the CYC-1 promoter of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. P Natl Acad SCI USA. 82, 8562–8566 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. & Dietrich F. S. Mapping of transcription start sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using 5′ SAGE. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2838–2851, 10.1093/nar/gki583 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale S. T. & Kadonaga J. T. The RNA polymerase II core promoter. Annu Rev Biochem 72, 449–479, 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161520 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer V. L., Wobbe C. R. & Struhl K. A wide variety of DNA sequences can functionally replace a yeast TATA element for transcriptional activation. Gene Dev. 4, 636–645 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogno I., Vallania F., Mitra R. D. & Cohen B. A. TATA is a modular component of synthetic promoters. Genome Res. 20, 1391–1397, 10.1101/gr.106732.110 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yean D. & Gralla J. Transcription reinitiation rate: a special role for the TATA box. Mol Cell Biol. 17, 3809–3816 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E. et al. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature 442, 772–778, 10.1038/nature04979 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Bryant G. O., Floer M., Spagna D. & Ptashne M. An effect of DNA sequence on nucleosome occupancy and removal. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 18, 507–509, 10.1038/nsmb.2017 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field Y. et al. Gene expression divergence in yeast is coupled to evolution of DNA-encoded nucleosome organization. Nat Genet 41, 438–445, 10.1038/ng.324 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A., Hughes A., Yassour M., Rando O. J. & Friedman N. High-resolution nucleosome mapping reveals transcription-dependent promoter packaging. Genome Res. 20, 90–100, 10.1101/gr.098509.109 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N. et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature 458, 362–366, 10.1038/nature07667 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I., Berman J. & Barkai N. The pattern and evolution of yeast promoter bendability. Trends Genet 23, 318–321, 10.1016/j.tig.2007.03.015 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giammartino D. C., Nishida K. & Manley J. L. Mechanisms and consequences of alternative polyadenylation. Mol Cell 43, 853–866, 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.017 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. & Botstein D. Two differentially regulated mRNAs with different 5′ ends encode secreted with intracellular forms of yeast invertase. Cell 28, 145–154 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkon R., Ugalde A. P. & Agami R. Alternative cleavage and polyadenylation: extent, regulation and function. Nat Rev Genet. 14, 496–506, 10.1038/nrg3482 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg R., Neilson J. R., Sarma A., Sharp P. A. & Burge C. B. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3′ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science 320, 1643–1647, 10.1126/science.1155390 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungewitter E. & Scrable H. Delta40p53 controls the switch from pluripotency to differentiation by regulating IGF signaling in ESCs. Gene Dev. 24, 2408–2419, 10.1101/gad.1987810 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon J. C. et al. p53 isoforms can regulate p53 transcriptional activity. Gene Dev. 19, 2122–2137, 10.1101/gad.1339905 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittendorf K. F., Deatherage C. L., Ohi M. D. & Sanders C. R. Tailoring of membrane proteins by alternative splicing of pre-mRNA. Biochemistry 51, 5541–5556, 10.1021/bi3007065 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aanes H. et al. Differential transcript isoform usage pre- and post-zygotic genome activation in zebrafish. BMC Genomics 14, 331, 10.1186/1471-2164-14-331 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhwald J. et al. Alternative splicing of a protein domain indispensable for function of transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) ion channels. J Biol Chem. 287, 36663–36672, 10.1074/jbc.M112.396663 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofk H. R. et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature 452, 230–233, 10.1038/nature06734 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A. et al. DBTSS as an integrative platform for transcriptome, epigenome and genome sequence variation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D87–91, 10.1093/nar/gku1080 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura F. et al. A large-scale full-length cDNA analysis to explore the budding yeast transcriptome. P Natl Acad SCI USA. 103, 17846–17851, 10.1073/pnas.0605645103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi U. et al. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science 320, 1344–1349, 10.1126/science.1158441 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelechano V., Wei W. & Steinmetz L. M. C. I. N. N. M. & Pmid. Extensive transcriptional heterogeneity revealed by isoform profiling. Nature 497, 127–131, 10.1038/nature12121 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee H. S. & Pugh B. F. Genome-wide structure and organization of eukaryotic pre-initiation complexes. Nature 483, 295–301, 10.1038/nature10799 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luykx P., Bajic I. V. & Khuri S. NXSensor web tool for evaluating DNA for nucleosome exclusion sequences and accessibility to binding factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W560–565, 10.1093/nar/gkl158 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan A., Younis A., Luykx P. & Khuri S. Prediction and analysis of nucleosome exclusion regions in the human genome. BMC Genomics 9, 186, 10.1186/1471-2164-9-186 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maicas E. & Friesen J. D. A sequence pattern that occurs at the transcription initiation region of yeast RNA polymerase II promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 3387–3393 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubliner S., Keren L. & Segal E. Sequence features of yeast and human core promoters that are predictive of maximal promoter activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 5569–5581, 10.1093/nar/gkt256 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillo D. & Hughes T. R. G+C content dominates intrinsic nucleosome occupancy. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 442, 10.1186/1471-2105-10-442 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer V. & Struhl K. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 14, 2570–2579 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Intrinsic histone-DNA interactions are not the major determinant of nucleosome positions in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 16, 847–852, 10.1038/nsmb.1636 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorch Y., Maier-Davis B. & Kornberg R. D. Role of DNA sequence in chromatin remodeling and the formation of nucleosome-free regions. Gene Dev. 28, 2492–2497, 10.1101/gad.250704.114 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Wu W. S., Liang H., Woo Y. & Li W. H. The spatial distribution of cis regulatory elements in yeast promoters and its implications for transcriptional regulation. BMC Genomics 11, 581, 10.1186/1471-2164-11-581 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I. & Barkai N. Two strategies for gene regulation by promoter nucleosomes. Genome research 18, 1084–1091, 10.1101/gr.076059.108 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y. et al. In vivo genome-wide profiling of RNA secondary structure reveals novel regulatory features. Nature 505, 696–700, 10.1038/nature12756 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y. et al. Landscape and variation of RNA secondary structure across the human transcriptome. Nature 505, 706–709, 10.1038/nature12946 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artieri C. G. & Fraser H. B. Evolution at two levels of gene expression in yeast. Genome Res. 24, 411–421, 10.1101/gr.165522.113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIsaac K. D. et al. An improved map of conserved regulatory sites for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 113, 10.1186/1471-2105-7-113 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venters B. J. & Pugh B. F. A canonical promoter organization of the transcription machinery and its regulators in the Saccharomyces genome. Genome Res. 19, 360–371, 10.1101/gr.084970.108 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege F. C. et al. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95, 717–728 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman J. E. et al. Genome Snapshot: a new resource at the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) presenting an overview of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D442–445 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wapinski I., Pfeffer A., Friedman N. & Regev A. Natural history and evolutionary principles of gene duplication in fungi. Nature 449, 54–61, 10.1038/nature06107 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubble J. et al. Implementation of GenePattern within the Stanford Microarray Database in Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D898–901 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews D. H., Sabina J., Zuker M. & Turner D. H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 288, 911–940 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuchty S., Fontana W., Hofacker I. L. & Schuster P. Complete suboptimal folding of RNA and the stability of secondary structures. Biopolymers 49, 145–165 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.