Abstract

Background

The optimal perioperative fluid resuscitation strategy for liver resections (LR) remains undefined. Goal-directed therapy (GDT) embodies a number of physiologic strategies to achieve an ideal fluid balance and avoid the consequences of over- or under-resuscitation.

Study Design

In a prospective randomized trial, patients undergoing LR were randomized to GDT using stroke volume variation (SVV) as an endpoint or standard perioperative resuscitation (STD). Primary outcome measure was 30-day morbidity.

Results

Between 2012 and 2014, 135 patients were randomized (GDT: 69 – STD: 66). Median age was 57yrs, and 56% were male. Metastatic disease comprised 81% of patients. Overall (35% GDT vs 36% STD, p=0.86) and Grade 3 morbidity (28% GDT vs 18% STD, p=0.22) were equivalent. Patients in the GDT arm received less intraoperative fluid (mean 2.0 L GDT vs 2.9 L STD, p<0.001). Perioperative transfusions were required in 4% (6% GDT vs 2% STD, p=0.37) and boluses in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) were administered to 24% (29% GDT vs 20% STD, p=0.23). Mortality rate was 1% (2/135 patients; both in GDT). On multivariable analysis, male gender, age, combined procedures, higher intraoperative fluid volume, and fluid boluses in PACU were associated with higher 30-day morbidity.

Conclusions

SVV-guided GDT is safe in patients undergoing LR and led to less intraoperative fluid. While the incidence of postoperative complications was similar in both arms, lower intraoperative resuscitation volume was independently associated with decreased postoperative morbidity in the entire cohort. Future studies should target extensive resections and identify patients receiving large resuscitation volumes, as this population is more likely to benefit from this technique.

Introduction

Perioperative fluid management has been recognized as an important factor with an impact on postoperative morbidity and recovery.[1, 2] An ideal balance between under and over resuscitation, which lead respectively to hypoperfusion or overload and tissue edema, is difficult to achieve using standard parameters (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, central venous pressure, or urine output) that poorly estimate preload and preload responsiveness. Goal directed fluid therapy (GDT) represents a spectrum of strategies that aim for optimal perioperative fluid management to ensure adequate end-organ perfusion, by monitoring arterial pressure and blood flow parameters including cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), stroke volume index (SVI), stroke volume variation (SVV), and oxygen delivery (DO2). GDT has been shown to be useful for optimizing hemodynamic status using dynamic physiologic endpoints of resuscitation.[3, 4] While the ideal endpoint and optimization strategy remain elusive, this physiologic approach has led to improved postoperative recovery and decreased complication rates in different surgical patient populations. [1, 5-8]

Improvements in operative techniques and perioperative care over the last two decades have led to reduced mortality after liver resection. On the other hand, perioperative morbidity remains an important issue, with as many as 40% of patients experiencing significant complications even at high volume centers. [9-12] Furthermore, postoperative morbidity has been linked with worse long term oncologic outcomes in patients undergoing resection for cancer, which remains the most common indication for liver resection.[13-17] While operative and patient specific factors are related to postoperative morbidity, there are few modifiable factors associated with the development of postoperative morbidity in these patients.

Stroke volume variation (SVV), which is the percentage of change between the maximal and minimal stroke volumes (SV) over a period of time divided by their average value, reflects variation in left ventricular output secondary to intra-thoracic pressure changes induced by mechanical ventilation. SVV has been shown to be an accurate predictor of fluid responsiveness -i.e. the ability of the left ventricle to increase SV (and subsequently CO) in response to administration of fluids.[18]

Using SVV as a resuscitation endpoint after low central venous pressure (LCVP) assisted liver resection, the present randomized controlled study evaluates the impact of GDT on the development of postoperative complications and postoperative recovery milestones in adult patients undergoing resection of primary and metastatic liver tumors.

Methods

Trial design, participants and intervention

This was a prospective, single-blinded, single institution, randomized trial evaluating the potential benefit of GDT in patients undergoing hepatic resection. Patients were allocated in a 1:1 ratio to undergo resuscitation after LCVP-assisted liver resection to predetermined hemodynamic end-points (GDT arm) or standard management as previously published.[19, 20] Randomization was stratified by diagnosis (metastatic liver disease compared to primary disease where primary disease encompassed liver cancer and extrahepatic biliary cancer including hilar cholangiocarcinoma with bile duct resection and reconstruction). All adult patients scheduled to undergo an open, elective liver resection (including those initially approached laparoscopically but converted to an open resection and those undergoing additional procedures) were assessed for eligibility and approached for participation in the preoperative clinic. Exclusion criteria included: active coronary, cerebrovascular, or congestive heart disease; atrial fibrillation or flutter; clinically significant pulmonary insufficiency with a resting oxygen saturation < 90%; active renal dysfunction (serum creatinine > 1.8 mg/dL); evidence of severe hepatic dysfunction or portal hypertension (coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, ascites); pregnancy; extreme body-mass index (> 45 or < 17).

Interventions

The Department of Anesthesia at MSKCC has a hepatobiliary team of anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists who perform >90% of all scheduled hepatobiliary cases at our institution. This allows for complete homogeneity in the anesthetic technique, particularly as it pertains to LCVP. All participants in the study received anesthesia from one of these practitioners, all of whom had had prior experience with the FloTrac sensor and SVV monitoring. All patients had continuous arterial waveform monitoring from the beginning of the operation and their SVV after induction (baseline) was recorded using the FloTrac sensor and EV1000 clinical platform (Edwards Lifesciences – Irvine, CA). SVV provides a measure of the patient’s intravascular volume and fluid responsiveness. Specifically, a large SVV (greater than 15%) predicts the ability of the left ventricle to increase the stroke volume and cardiac output in response to administration of intravenous fluid.

The details of the LCVP technique have been previously published.[19-21] Briefly, LCVP consists of two phases: a pre-hepatic transection which takes advantage of strict fluid restriction (overnight fluid replacement is withheld and maintenance fluid requirement at 1 ml/kg/hr of balanced crystalloid solution is infused until the liver resection is completed) and the vasodilatory effect of anesthetic agents to provide LCVP; during this phase, anesthesia is maintained with a combination of isoflurane in oxygen, and fentanyl. Isoflurane provides vasodilation with minimal myocardial depression. Shortly before transection of the liver, sublingual nitroglycerine (SLNTG) is applied. This combination, isoflurane, fentanyl and SLNTG readily provides the favorable LCVP environment for hepatic resection. Second phase starts at the completion of transection and aims to restore euvolemia. At this point, enrolled patients were randomized to standard resuscitation (1:1 blood loss replacement with colloid, and crystalloid infusion at 6 ml/kg/hr of total operative time to restore the calculated insensible losses and maintenance requirements) or GDT resuscitation (1:1 blood loss replacement with colloid, and albumin bolus infusions to restore SVV to a value ≤ 2 standard deviations from their baseline after induction. Crystalloid infusion was continued at 1ml/kg/hr). For both arms, additional fluid boluses were administered for systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg or urine output < 25ml/hr. Packed red-blood cells (PRBC) for hemoglobin <7 g/dL, fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) or platelets were given in selected patients, at the request of the surgeon, either during the resection if hemostasis was felt to be inadequate, or postoperatively for markedly abnormal parameters (international normalized ratio (INR) >1.8-2.0 or platelets < 80,000mcL) in the setting of bleeding complications; this at the discretion of the treating surgeon. Management in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) followed standard resuscitation protocols and was equal for both arms: 1.2 ml/kg/hr of maintenance fluid with rescue fluid boluses (250 ml bolus of 5% albumin) administered for sustained systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg, or urine output below 25 ml/hr over 2 consecutive hours.

Outcomes

Primary endpoint was the incidence of 30-day overall postoperative morbidity as defined by the MSKCC surgical secondary events (SSE) program. All complications were discussed at a biweekly morbidity and mortality conference, graded and prospectively recorded into the SSE database. Research personnel directly involved in the protocol did not participate in this process. A research study assistant queried the SSE database at 30 days after each operation and prospectively collected morbidity data for patients enrolled in the study. Secondary endpoints included 30-day Grade 3 or greater morbidity, total fluid volume administered perioperatively and for the complete hospital stay, the need for fluid boluses for low urine output or hypotension, vasopressor utilization, blood transfusion rates, end-organ perfusion markers (eGFR, oxygen delivery [DO2], and arterial lactate), and hemodynamic parameters that included amount of time with low CO (< 4 L/min), low CI (< 2 L/min/m2) and elevated SVV intraoperatively (> 15%), as well as the stroke volume (SV) and stroke volume index (SVI) upon arrival to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). Postoperative recovery milestones evaluated included day of discontinuation of maintenance fluids, tolerance of liquid and solid intake, duration of bladder drainage (Foley catheter), and day of return of bowel function.

Statistical considerations

Based on our institution’s historical morbidity rate of 30%, a sample size of 270 patients was estimated to provide 80% power for detecting a 15% absolute risk reduction in the incidence of postoperative morbidity rate (two-sided Type I error of 5%). Patients were to be randomized 1:1 to the two arms (135 per arm). An interim analysis halfway through enrollment, using O’Brien-Fleming boundaries both for efficacy and futility, was built into the protocol.

The intraoperative randomization arm was concealed by sequentially numbered, dark envelopes that were only opened after the resection phase had been completed and were otherwise kept in a locked container. Patients remained blinded to their group assignment throughout the trial. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of the primary outcome by randomization group (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for stratified primary outcome). Secondary endpoints were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, except for the categorical endpoint of blood transfusion for which Fisher’s exact test was used.

End-organ perfusion markers and liver function tests at various time points (preoperative to postoperative) were compared between groups using two-way ANOVA with time as a factor variable. Comparisons between groups of the hemodynamic parameters (at 20 second increments) during the intraoperative resuscitation and PACU phases were performed with a mixed-effects model over time. An identifier for individual patients was included as a random effect to account for within-person correlation, along with an AR1 correlation structure for the residuals. A post-hoc analysis was conducted evaluating variables associated with 30-day overall morbidity. Demographics, operative, hemodynamic, and laboratory data in the perioperative period were evaluated in a univariable logistic model and those with significance at the 0.1 level were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variables with P < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 12.1 (StataCorp LP – College Station, TX) and R 3.1.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). This trial was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01596283).

Results

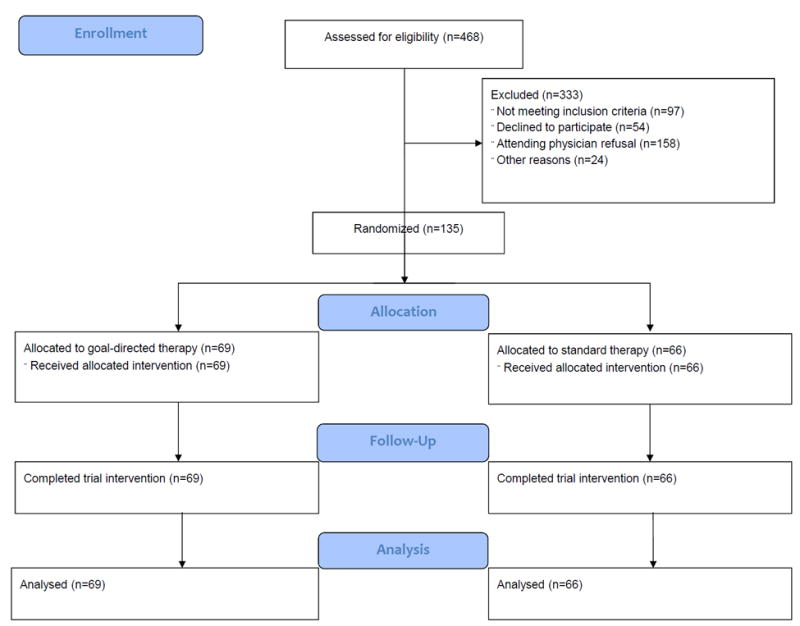

Between June 2012 and February 2014, 468 patients underwent a liver resection and were assessed for eligibility. 135 patients were randomized to either GDT (n=69) or standard management (n=66). All patients completed trial intervention and were included in the intention to treat analysis for the primary outcome and all secondary end-points (Figure 1). There were no deviations from randomization. Enrollment was stopped following planned interim analysis after 135 patients were accrued in accordance with a pre-established futility rule. Demographics, baseline clinical presentation, and operative data are presented in Table 1. Treatment arms were comparable in all baseline demographics variables; similarly operative interventions and immediate operative outcomes (length of surgery, blood-loss, Pringle time, and complications) are comparable between arms.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram of patients assessed for eligibility and randomized.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics, Clinical and Operative Characteristics

| Characteristic | GDT (n=69) | Standard (n=66) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic* | |||

| Male, n (%) | 36 (52) | 39 (59) | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 55 (13) | 58 (14) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 29 (5) | 30 (8) | |

| ASA, n (%) | |||

| I-II | 41 (59) | 37 (56) | |

| III-IV | 28 (41) | 29 (44) | |

| Diagnosis* | |||

| Primary, n (%) | 13 (19) | 13 (20) | |

| Metastatic, n (%) | 56 (81) | 53 (80) | |

| Operative data | |||

| Minor resection, n (%) | 32 (46) | 28 (42) | 0.73 |

| Major resection, n (%) | 37 (54) | 38 (58) | 0.73 |

| IHAP placement, n (%) | 19 (28) | 20 (30) | 0.85 |

| Combined procedure, n (%) | 20 (29) | 13 (20) | 0.23 |

| Length of surgery, h, mean ± SD | 4.5 (2) | 4.1 (1) | 0.21 |

| Estimated blood-loss (mL), mean ± SD | 637 (462) | 533 (351) | 0.24 |

| Pringle maneuver, n (%) | 53 (77) | 44 (67) | 0.25 |

| Pringle time, min, mean ± SD | 31 (16) | 28 (15) | 0.51 |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | 6 (9) | 4 (6) | 0.74 |

p Values are not provided for preoperative characteristics.

The primary outcome (30-day morbidity) occurred in 24/69 (35%) in the GDT arm and 24/66 (36%) in the standard treatment arm. There was no difference in overall morbidity or in stratified analysis by primary liver vs metastatic disease; (Table 2). Patients in the GDT arm received on average 900 ml less fluid during the resuscitation phase (intraoperative post-resection phase) before achieving the pre-established resuscitation goal (return to baseline SVV). This difference was statistically significant and remained as such after adjusting for weight (Table 2). Other surrogates of intraoperative resuscitation (i.e., urine output, requirement for transfusion, and intraoperative use of vasoactive agents), were comparable between both arms. The need for rescue fluid boluses in PACU was not significantly different between arms, however, the total amount of fluid in the entire hospital stay was equivalent.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

| GDT (n=69) | Standard (n=66) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall morbidity, n (%) | 24 (35) | 24 (36) | 0.86 |

| Overall morbidity by primary, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| Primary liver | 4 (31) | 6 (46) | |

| Metastatic disease | 20 (36) | 18 (34) | |

| Grade ≥ 3 morbidity | 19 (28) | 12 (18) | 0.22 |

| Low CO duration, min, mean ± SD | 21 (113) | 12 (48) | 0.42 |

| Low CI duration, min, mean ± SD | 2.2 (5.4) | 3 (7.8) | 0.58 |

| High SVV duration, min, mean ± SD | 7.7 (14) | 8.3 (23.7) | 0.08 |

| Operative fluid volume, L, mean ± SD | 2.0 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.0) | <0.001* |

| Operative fluid volume mL/kg, mean ± SD | 24.7 (13.5) | 34.5 (10.8) | <0.001* |

| Urine output during surgery, L, mean ± SD | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.10 |

| Blood transfusion, n (%) | 4 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.37 |

| Vasopressor use, n (%) | 40 (58) | 38 (58) | 1.00 |

| Resuscitation parameters, mean ± SD | |||

| SV in PACU (mL) | 91 (30) | 89 (31) | 0.98 |

| SVI in PACU (mL/m2/beat) | 47 (15) | 46 (13) | 0.79 |

| End-organ perfusion markers (mM/L) | |||

| Baseline arterial lactate | 0.8(0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.98 |

| Arterial lactate after resection | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.4) | 0.98 |

| Arterial lactate after resuscitation | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.5) | 0.19 |

| Arterial lactate POD 1 | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.29 |

| PACU fluid volume, L, mean ± SD | 1.8 (1.4) | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.79 |

| PACU Urine output, L, mean ± SD | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.5) | 0.07 |

| Fluid bolus for UOP/SBP in PACU, n (%) | 20 (29) | 13 (20) | 0.23 |

| Need for postoperative diuresis, n (%) | 43 (62) | 39 (59) | 0.73 |

| Postoperative fluid volume, L, mean ± SD | 12 (5) | 12 (5) | 0.77 |

| Milestones, d (range) | |||

| Oral liquid tolerance | 3 (2 - 3) | 3 (2 - 3) | 0.45 |

| Discontinuation of IV fluids | 3 (3 -4) | 3 (3 - 4) | 0.52 |

| Foley discontinuation | 3 (2 - 4) | 3 (2 -4) | 0.83 |

| Regular diet tolerance | 4 (4 - 5) | 4 (4 - 5) | 0.35 |

| Days until return of bowel function | |||

| Flatus | 4 (3 - 5) | 4 (3 - 5) | 0.94 |

| Stool | 5 (4 - 6) | 5 (4 - 6) | 0.69 |

| Postoperative length of stay, d (range) | 7 (6 - 8) | 6 (5 - 8) | 0.34 |

| 60-d Readmission, n (%) | 14 (20) | 12 (18) | 0.83 |

Significant.

Low CO, <4 L/min; low CI, <2 L/min/m2; high SVV, >15%; POD, postoperative day; PACU, post-anesthesia care unit; UOP, urine output; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

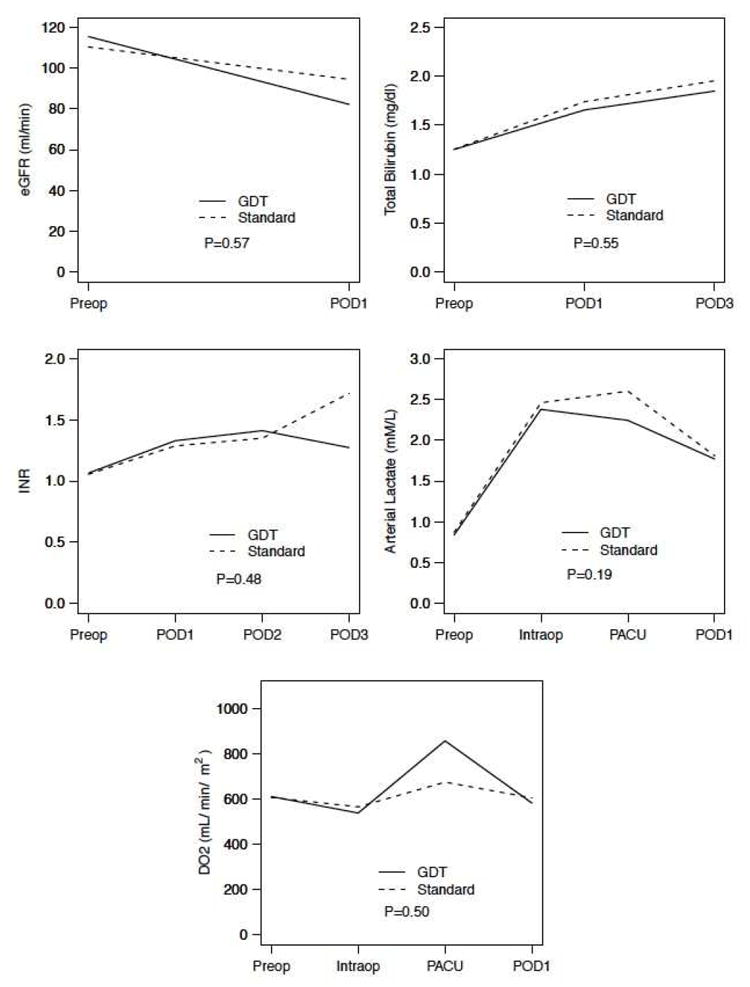

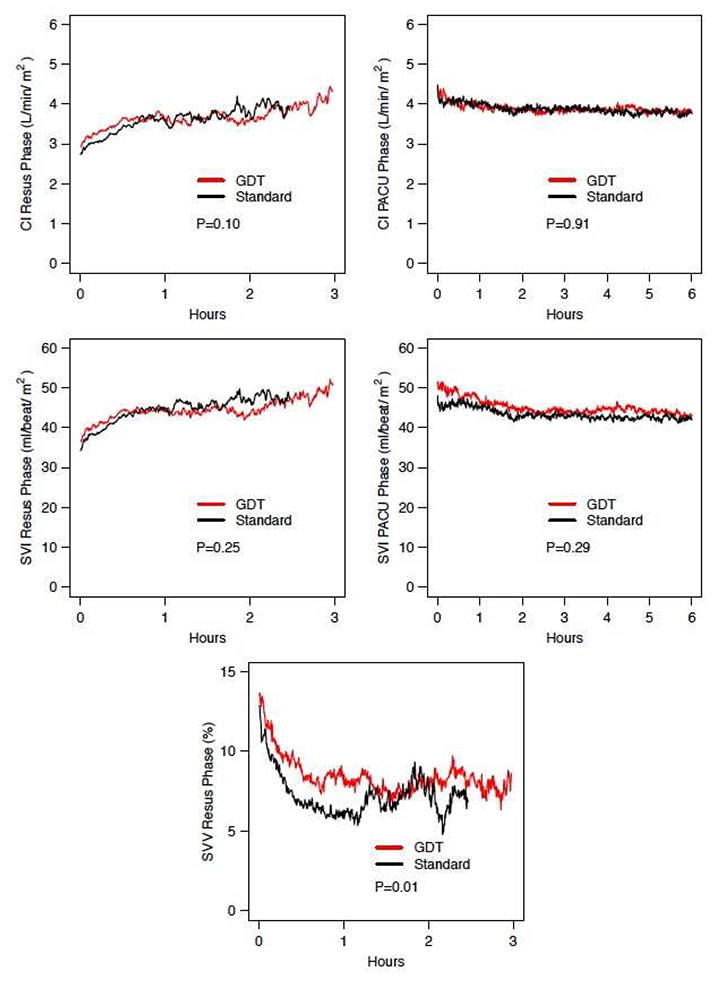

Patients in both arms experienced a transient elevation in arterial lactate levels during the LCVP phase of the operation (resection phase). Similarly, the dynamics of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), arterial lactate, oxygen delivery (DO2), international normalized ratio (INR), and total bilirubin were equivalent in both groups, Figure 2A. The total time that patients experienced low CO and CI intraoperatively was similar between both arms. Likewise, the mean SV and SVI upon arrival to PACU were comparable as shown in Table 2. Figure 2B compares the hemodynamic trends between arms during the resuscitation time (time zero marks the initiation of the resuscitation phase) and the PACU phases. CI and SVI show close overlap during both the intraoperative resuscitation period and the PACU phase, while SVV is significantly different between arms. Both GDT and STD arms show a steep drop in the early part of the resuscitation phase to levels below 10% indicating adequate resuscitation. Postoperative milestones and specific morbidity are reported in tables 2 and 3. There were no differences in the time to return of bowel function, the postoperative length of stay, or the readmission rate between arms. Grade 3 or greater morbidity was experienced by 19/69 (27%) patients in the GDT arm and 12/66 (18%) in the standard arm; P: 0.22. The most common complications are listed in table 3. The only significant difference in postoperative morbidity was a higher incidence of pleural effusion requiring drainage in the GDT arm (16% vs 2%; P: 0.03). The median time for diagnosis of these effusions was 8 days (4-20) after surgery. On subgroup analysis of patients who underwent a major resection (≥ 3 segments, n=75), there was a non-significant trend toward lower overall (30% vs 50%; P: 0.10) and grade ≥ 3 morbidity (22% vs 26%; P: 0.8) in the GDT arm. Patients who underwent combined colorectal (n = 31) or pancreatic procedures (n = 2) experienced overall and grade ≥ 3 morbidity rates that were comparable between GDT and standard arms (overall: 60% vs 54%; P: 1.00 - grade ≥ 3: 45% vs 31%; P: 0.49). None of these subgroup analyses reached statistical significance. There were 2 deaths in the entire cohort, both from the GDT arm, at 69 and 94 days postoperatively; both secondary to liver failure on patients who had undergone right trisegmentectomies for metastatic colorectal cancer. No patient experienced any adverse event directly related to the use of the monitoring device or the arterial line placement.

Figure 2.

(A) Mean values of dynamics of end-organ perfusion markers (arterial lactate, eGFR, and DO2) and liver function tests (Total bilirubin and INR) between patients in the GDT and Standard Arms. (B) Comparison of the hemodynamic parameters during the intraoperative resuscitation phase and PACU for patients in the standard vs goal-directed arm (GDT). CI, Cardiac index; SVI, stroke volume index; SVV, stroke volume variation. INR, international normalized ratio; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate using modified in renal diet (MDRD) formula; DO2, oxygen delivery; GDT, goal-directed therapy arm; Preop, preoperative value; POD, postoperative day; PACU, post-anesthetic care unit; Resus, resusciation. P, two-way ANOVA between randomization arms.

Table 3.

Postoperative Complications

| GDT (n=69) | Standard (n=66) | |

|---|---|---|

| Complications, total (grade ≥3) | ||

| Intra-abdominal infection or abscess | 13 (13) | 10 (9) |

| Pleural effusion | 10 (9) | 1 (1) |

| Wound infection | 5 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Liver dysfunction / failure | 4 (2) | 1 (0) |

| Non-infected intra-abdominal / intra-thoracic fluid collection | 4 (3) | |

| Biliary anastomotic leak | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Biloma | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Hemorrhage | 3 (1) | |

| Renal failure | 3 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Sepsis | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 24 (9) | 19 (5) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2 (3) | 0 |

Top ten most common complications seen in the entire cohort. Values represent total number and total ≥ grade 3. Low numbers preclude meaningful statistical comparison.

Clinical, hemodynamic and laboratory variables and their association with development of postoperative morbidity are shown in Table 4. In univariable analyses, male gender, combined procedures, longer duration of surgery, higher estimated blood loss, higher total intraoperative fluid volume, higher intraoperative urine output and need for fluid boluses in PACU for low urine output or blood pressure were significantly associated with greater likelihood of developing 30-day postoperative complications (Table 4). On multivariable analysis, controlling by body mass index (BMI), significant results included the male gender, age, combined procedure, total intraoperative fluid and need for fluid boluses. None of the hemodynamic variables measured as part of the protocol (CO, CI, SVV, SV) were significant in either of these models.

Table 4.

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Postoperative Morbidity

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Randomization, standard | 1.07 | 0.53-2.17 | 0.848 | |||

| Sex, male | 2.72 | 1.31-5.91 | 0.009 | 2.89 | 1.22-7.24 | 0.019 |

| Age, y | 1.03 | 1.00-1.06 | 0.077 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.07 | 0.054 |

| Combined liver and colon resection, yes | 3.42 | 1.53-7.84 | 0.003 | 2.85 | 1.16-7.19 | 0.024 |

| Length of surgery, h | 1.32 | 1.04-1.68 | 0.024 | |||

| Estimated blood loss, 100 mL | 1.10 | 1.01-1.21 | 0.035 | |||

| Total fluids in OR, mL | 1.64 | 1.20-2.29 | 0.002 | 1.50 | 1.04-2.20 | 0.034 |

| Urine output in OR per 100 mL | 1.03 | 1.00-1.05 | 0.035 | |||

| Fluid bolus for UOP/SBP in PACU | 2.88 | 1.29-6.54 | 0.010 | 3.38 | 1.36-8.79 | 0.010 |

| BMI | 1.00 | 0.98-1.03 | 0.925 | |||

Discussion

Goal-directed fluid therapy refers to operative and immediate postoperative techniques aimed at modifying the hemodynamic status of patients undergoing major surgery. The ultimate goal of these techniques is to achieve optimal oxygen delivery while avoiding the deleterious complications associated with over- and under-resuscitation.[22, 23] First described decades ago, [22-24] this concept has gained increased attention in the recent years and it has been suggested that it could improve various perioperative outcomes in selected patients. Randomized trials, however, have shown mixed results. While most trials agree in the safety of these techniques, perioperative benefits have been seen only in selected procedures and patient populations. Although perioperative fluid goals should be independent of the type of surgery, certain procedure-specific caveats should be considered. For liver resection, these include minimizing blood loss, appropriate transfusion strategy, and stability during vascular clamping and unclamping. Twenty years ago, our group developed and reported a simple, effective and reproducible technique for decreasing the intraoperative blood loss in patients undergoing liver resection.[19] LCVP-assisted liver resection resulted in improved outcomes and has become the standard approach at our institution [20, 21] and others.[25-28] The success of this approach hinges on effective communication between the anesthesia and surgical teams during the operative and perioperative periods. Lower blood loss provides improved operative outcome and may also offer long-term oncologic benefit by avoiding allogeneic blood transfusions.[29]

Historically, LCVP-assisted hepatic resection required a central venous catheter to provide hemodynamic information and reliable access in case rapid resuscitation was required. Improvements in surgical techniques have significantly decreased the average blood loss during liver resection and currently large-bore peripheral intravenous access is sufficient to safely perform these operations. Furthermore, we’ve found CVP measurement to be both unreliable and unnecessary to practice LCVP-assisted anesthesia, and our group has abandoned the routine use of central venous lines. LCVP is currently based on fluid restriction during the resection phase of the operation and visual inspection of the vena cava by the surgeon and on an estimation of the rate of back-bleeding during parenchymal transection. Once hemostasis has been achieved, infusion of an assumed volume of required resuscitation restores euvolemia. This approach while proven safe,[21] may under or overestimate the fluid needs of these patients and may not provide the optimal amount of resuscitation.

Pulse wave contour analysis has been previously validated as a reliable dynamic method to assess fluid status and predict fluid responsiveness during general and hepatobiliary procedures.[30-33] Dunki-Jacobs et al recently reported a prospective study evaluating the correlation of SVV with CVP in patients undergoing liver resection.[34] They found a strong correlation between a low CVP and an elevated SVV (R2: 0.85). They concluded that minimally invasive assessment of SVV is reliable and could safely replace central venous monitoring of patients undergoing liver resection. Their study, however, did not attempt to establish what the adequate endpoints of resuscitation are after liver transection has been completed.

In the present single-center randomized controlled trial, we did not use SVV as a surrogate for LCVP but instead used it to guide resuscitation after LCVP-assisted liver resection. Despite a lower amount of intraoperative fluids in the intervention arm, we found no difference in the development of postoperative complications at 30 days between GDT patients and patients allocated to standard treatment. Based on the findings at interim analysis and according to the prespecified futility rule, enrollment was stopped half-way through accrual. Postoperative fluid volume administered, intraoperative need for fluid boluses to correct low urine output or hypotension, vasopressor use, blood transfusion rates, and end-organ perfusion markers (eGFR, DO2, and arterial lactate) were similar between the two arms. In this cohort, GDT was a safe monitoring technique that adequately guided resuscitation and resulted in no untoward effects in patients randomized to it. It was associated with approximately one liter less of intraoperative fluid for resuscitation and there was a non-significant trend toward fewer complications in patients undergoing major hepatic resections, suggesting that these may represent the ideal target group for this technique.

Recently, a large multi-institutional RCT was performed to address this concept in ‘high-risk’ patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery.[1] This trial, powered to detect a 12.5% absolute risk reduction in a composite end-point of 30-day morbidity and mortality (from 50% to 37.5%), found no significant difference between the intervention arm and patients who underwent usual care. However, as part of the same report, the authors included their results in a meta-analysis of 38 randomized controlled trials which ultimately showed that goal-directed resuscitation was associated with a 10% absolute risk reduction in the incidence of postoperative complications (mainly accounted for by lower infection rates), and a reduction in length of hospital stay. There seems to be consensus in the literature regarding the fact that the benefit of perioperative goal-directed strategies is limited to high-risk patients. [23]

Arguably, the patient population represented in our study is not ‘high risk’. The inherent selection process for patients with cancer who reach operative therapy and the strict exclusion criteria in our study, restricted our study subjects to a relatively healthy pool. On subgroup analysis, patients who underwent major liver resection (defined as ≥3 Couinaud segments) had a lower incidence of postoperative morbidity if randomized to the GDT arm. This difference did not reach statistical significance at the time of early termination of the study, however, this finding may point to a subgroup of patients that could potentially benefit from more judicious perioperative fluid management strategies including functional hemodynamics. The large fluid shifts and prolonged operative time in patients undergoing major resections, as well as the stress of postoperative liver regeneration, likely place these patients in a category of “high risk”. Interestingly, even though the volume of intraoperative resuscitation was independently associated with postoperative morbidity, there was no significant difference in morbidity between the two arms despite a significant difference in resuscitation volume. The significant difference on the incidence of pleural effusions (14% vs 2% - all of them right sided effusions) is hard to explain in the context of essentially equal extent of operation and similar postoperative outcomes. For perspective, our historical rate of pleural effusion approaches 5%, versus an overall incidence of 8% in all patients in this trial, which could be at least partially explained by increased detection due to prospective assessment. We believe the difference between arms represents a type I error that would have otherwise been balanced if the trial had reached complete accrual.

Patients in both arms had equivalent resuscitation status at completion of the operation and the hemodynamic curves during the PACU phase are essentially identical. These findings speak to the adequacy of our current resuscitation strategies that restore these hemodynamic variables to acceptable levels. Both arms were adequately resuscitated intraoperatively, however both arms reached SVV levels during the resuscitation phase that were well below the point of fluid responsiveness, indicating administration of excess fluid that did not contribute to improved CO. Arguably both arms could have safely received less resuscitation fluid intraoperatively. In addition to goal-directed resuscitation, other perioperative strategies are currently being developed to improve the outcome of patients undergoing major operations. In open liver resection, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways have been shown to decrease postoperative morbidity, LOS, and improve postoperative quality of life.[35, 36] ERAS management algorithms may provide alternative means (beyond technical operative maneuvers) to improve the ultimate outcome of these patients. However, since GDT is part of a multimodality fast-track approach in these studies, its individual contribution to the ultimate outcome is difficult to estimate.

Our trial has several limitations. First, practitioners involved in patient care could not be blinded to the treatment allocation or to the hemodynamic data on either arm. While the primary outcome was assessed in an independent manner and not influenced by personnel involved with the trial, the amount and type of resuscitation after the patients were transferred to the surgical ward may have been ultimately influenced by perioperative events despite proposed management guidelines established in the protocol.

Furthermore, using SVV as a resuscitation endpoint may be questioned versus the use of other parameters such as optimal stroke volume, CO, CI or oxygen delivery. By design, our protocol established that estimated blood loss would be replaced in a 1:1 ratio for both arms, before considering additional fluid for restoration of euvolemia either SVV-guided (GDT arm) or by the pre-established equation (STD arm). We did not anticipate that blood loss replacement alone could lead to SVV overcorrection (figure 2b). While we set a goal SVV no greater than 2 standard deviations from baseline, we did not set a lower limit which would have prevented this phenomenon and led to a more pronounced intraoperative resuscitation volume difference between arms. Both arms received fluid boluses in the LCVP phase for low blood pressure and or low urine output, both standard parameters that are not reliable for preload or preload responsiveness which most likely increased resuscitation volume in both arms.

Our traditional resuscitation phase (which ends at the completion of the case) may be too short and should be extended to the immediate postoperative period. While our study limited resuscitation goals to the intraoperative hemodynamics, an approach that uses intraoperative SVV-guided resuscitation (which in our study resulted in less intraoperative fluid) coupled with hemodynamic optimization in the immediate postoperative period, may provide the ideal resuscitation while still avoiding fluid overload. Perhaps the time has come to add a third phase to our LCVP-assited liver resection: hemodynamic optimization. This third phase would invariably occur in PACU and would require close hemodynamic monitoring and judicious use of fluid resuscitation (as long as dynamic indices predict fluid responsiveness – i.e. SV increases with fluid challenge) and the addition of low-dose pressors and/or inotropes to optimize oxygen delivery while avoiding fluid overload.

Conclusion

Goal-directed fluid therapy proved safe and significantly reduced the volume of intraoperative resuscitation in patients undergoing liver resection. While total fluid administered was independently associated with postoperative morbidity on multivariable analysis, the incidence of postoperative complications was similar between both arms in the study. Future studies should consider coupling SVV-guided intraoperative resuscitation with goal-directed resuscitation in the immediate postoperative period to achieve sustained hemodynamic optimization. A trend toward fewer complications in patients undergoing major resections may point to the patient population who may ultimately benefit from careful hemodynamic monitoring and goal-directed resuscitation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David O’Connor, CRNA, Michael Kosalka, CRNA, and Timothy Donoghue, CRNA for their valuable contribution to the performance of this trial.

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, MacDonald N, et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA. 2014;311:2181–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalfino L, Giglio MT, Puntillo F, et al. Haemodynamic goal-directed therapy and postoperative infections: earlier is better. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15:R154. doi: 10.1186/cc10284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundgaard-Nielsen M, Secher NH, Kehlet H. ‘Liberal’ vs. ‘restrictive’ perioperative fluid therapy--a critical assessment of the evidence. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Della Rocca G, Pompei L. Goal-directed therapy in anesthesia: any clinical impact or just a fashion? Minerva Anestesiol. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng K, Li J, Cheng H, Ji FH. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on stroke volume variations improves fluid management and gastrointestinal perfusion in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre. 2014 doi: 10.1159/000363573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salzwedel C, Puig J, Carstens A, et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy based on radial arterial pulse pressure variation and continuous cardiac index trending reduces postoperative complications after major abdominal surgery: a multi-center, prospective, randomized study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R191. doi: 10.1186/cc12885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng H, Guo H, Ye JR, et al. Goal-directed fluid therapy in gastrointestinal surgery in older coronary heart disease patients: randomized trial. World J Surg. 2013;37:2820–2829. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reydellet L, Blasco V, Mercier MF, et al. Impact of a goal-directed therapy protocol on postoperative fluid balance in patients undergoing liver transplantation: a retrospective study. Annales francaises d’anesthesie et de reanimation. 2014;33:e47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan ST, Mau Lo C, Poon RT, et al. Continuous improvement of survival outcomes of resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 20-year experience. Ann Surg. 2011;253:745–758. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000029003.66466.B3. discussion 406-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamiyama T, Nakanishi K, Yokoo H, et al. Perioperative management of hepatic resection toward zero mortality and morbidity: analysis of 793 consecutive cases in a single institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virani S, Michaelson JS, Hutter MM, et al. Morbidity and mortality after liver resection: results of the patient safety in surgery study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correa-Gallego C, Gonen M, Fischer M, et al. Perioperative complications influence recurrence and survival after resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013;20:2477–2484. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2975-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito H, Are C, Gonen M, et al. Effect of postoperative morbidity on long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2008;247:994–1002. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816c405f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chauhan A, House MG, Pitt HA, et al. Post-operative morbidity results in decreased long-term survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farid SG, Aldouri A, Morris-Stiff G, et al. Correlation between postoperative infective complications and long-term outcomes after hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg. 2010;251:91–100. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfda3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, et al. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242:326–341. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. discussion 341-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkenstadt H, Margalit N, Hadani M, et al. Stroke volume variation as a predictor of fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing brain surgery. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:984–989. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham JD, Fong Y, Shriver C, et al. One hundred consecutive hepatic resections. Blood loss, transfusion, and operative technique. Arch Surg. 1994;129:1050–1056. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420340064011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melendez J. Perioperative outcomes of major hepatic resections under low central venous pressure anesthesia: blood loss, blood transfusion, and the risk of postoperative renal dysfunction. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:620–625. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Correa-Gallego C, Berman A, Denis SC, et al. Renal function after low central venous pressure-assisted liver resection: assessment of 2116 cases. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:258–264. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lees N, Hamilton M, Rhodes A. Clinical review: Goal-directed therapy in high risk surgical patients. Crit Care. 2009;13:231. doi: 10.1186/cc8039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perel A, Habicher M, Sander M. Bench-to-bedside review: functional hemodynamics during surgery - should it be used for all high-risk cases? Crit Care. 2013;17:203. doi: 10.1186/cc11448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyd O, Grounds RM. Our study 20 years on: a randomized clinical trial of the effect of deliberate perioperative increase of oxygen delivery on mortality in high-risk surgical patients. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2107–2114. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNally SJ, Revie EJ, Massie LJ, et al. Factors in perioperative care that determine blood loss in liver surgery. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:236–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurusamy KS, Li J, Vaughan J, et al. Cardiopulmonary interventions to decrease blood loss and blood transfusion requirements for liver resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD007338. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007338.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin CX, Guo Y, Lau WY, et al. Optimal central venous pressure during partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international. HBPD Int. 2013;12:520–524. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huntington JT, Royall NA, Schmidt CR. Minimizing blood loss during hepatectomy: a literature review. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:81–88. doi: 10.1002/jso.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kooby DA, Stockman J, Ben-Porat L, et al. Influence of transfusions on perioperative and long-term outcome in patients following hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2003;237:860–869. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000072371.95588.DA. discussion 869-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Compton FD, Zukunft B, Hoffmann C, et al. Performance of a minimally invasive uncalibrated cardiac output monitoring system (Flotrac/Vigileo) in haemodynamically unstable patients. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:451–456. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer J, Boldt J, Mengistu AM, et al. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy based on autocalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis reduces hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R18. doi: 10.1186/cc8875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGee WT. A simple physiologic algorithm for managing hemodynamics using stroke volume and stroke volume variation: physiologic optimization program. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24:352–360. doi: 10.1177/0885066609344908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solus-Biguenet H, Fleyfel M, Tavernier B, et al. Non-invasive prediction of fluid responsiveness during major hepatic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:808–816. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunki-Jacobs EM, Philips P, Scoggins CR, et al. Stroke volume variation in hepatic resection: a replacement for standard central venous pressure monitoring. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:473–478. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones C, Kelliher L, Dickinson M, et al. Randomized clinical trial on enhanced recovery versus standard care following open liver resection. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1015–1024. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes MJ, McNally S, Wigmore SJ. Enhanced recovery following liver surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2014;16:699–706. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]